Forensic Genomic Analysis Determines That RaTG13 Was Likely Generated from a Bat Mating Plug

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

Sequence Data

3. Methods

3.1. Microbial Analysis

3.2. Mitochondrial Genome Analysis

3.3. Mitochondrial rRNA Phylogenetic Analysis

3.4. Viral Genome Abundance Analysis

3.5. Nuclear Genome Mapping

3.6. Transcriptome Analysis

3.7. Comparative Transcriptomics

3.8. GO Enrichment

4. Results

4.1. Numbers of Reads Matching SSU rRNA

4.2. Ratio of Eukaryotic to Bacterial SSU rRNA Reads

4.3. Microbial Analysis of the RaTG13 Dataset

4.4. Microbial Community Comparison of RaTG13 and Clade 7896

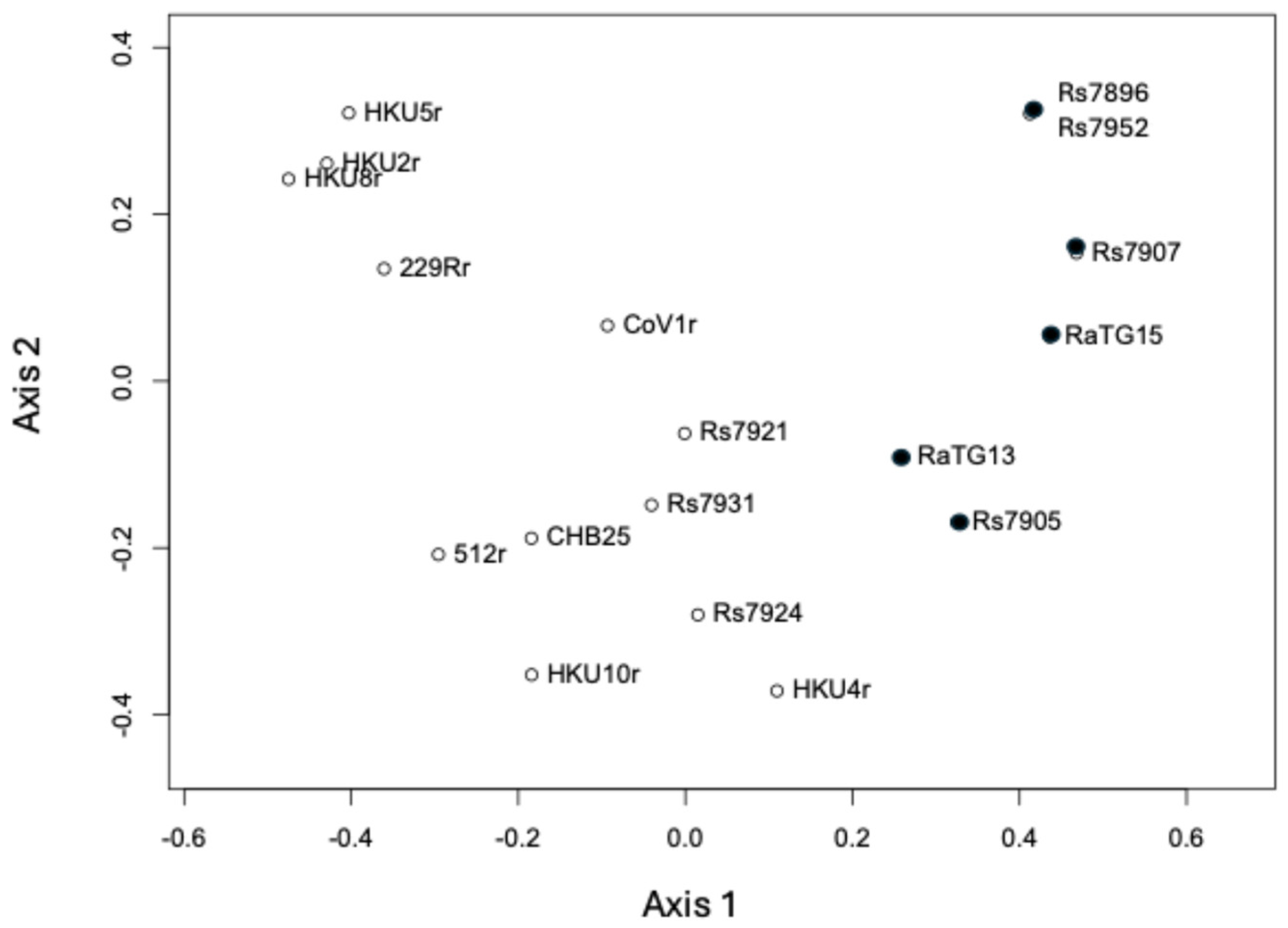

4.5. Viral Genome Abundance Comparison

4.6. Mitochondrial Analysis

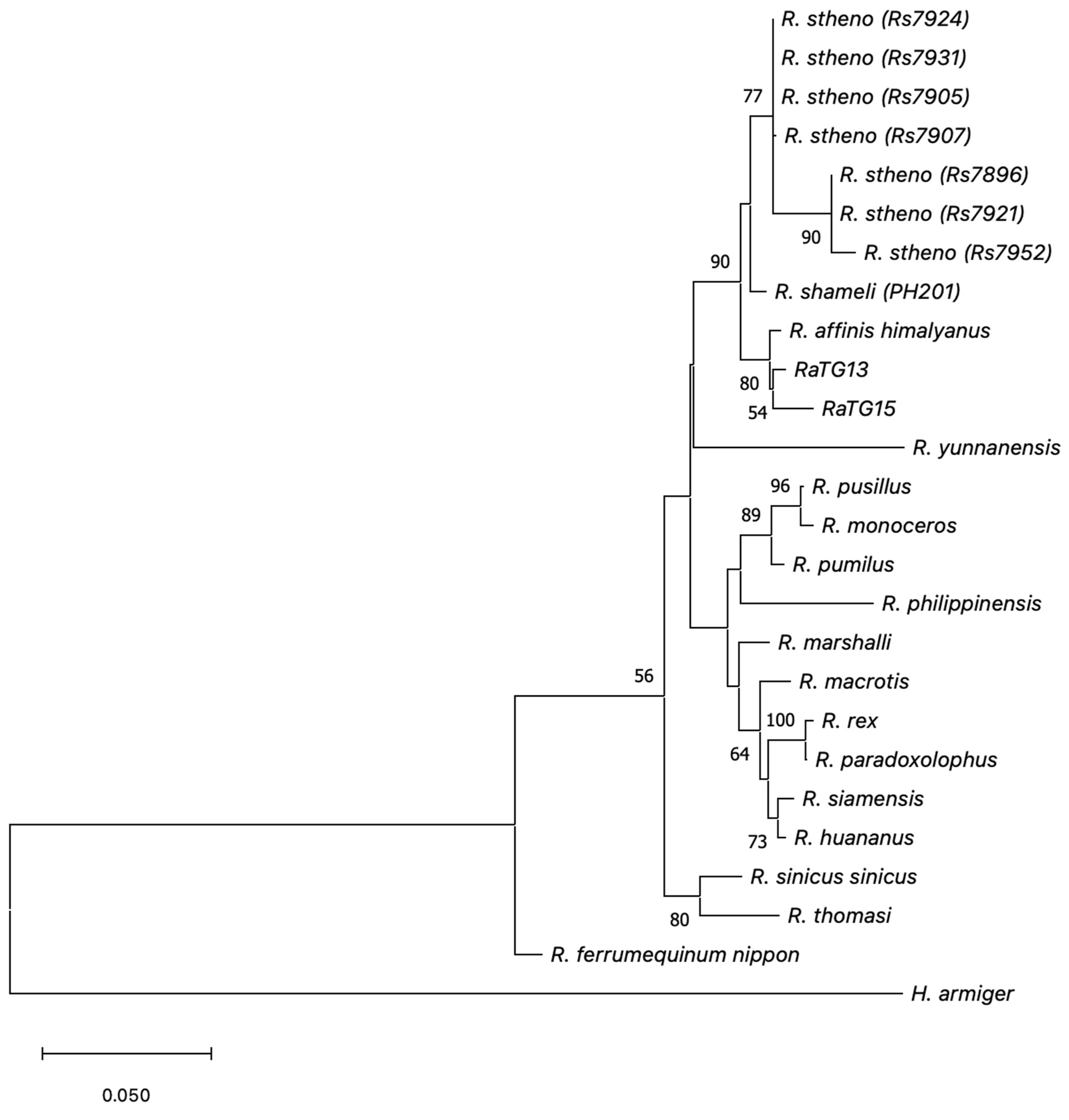

4.7. Mitochondrial SSU rRNA Phylogenetic Analysis

4.8. Nuclear Genome Mapping Analysis

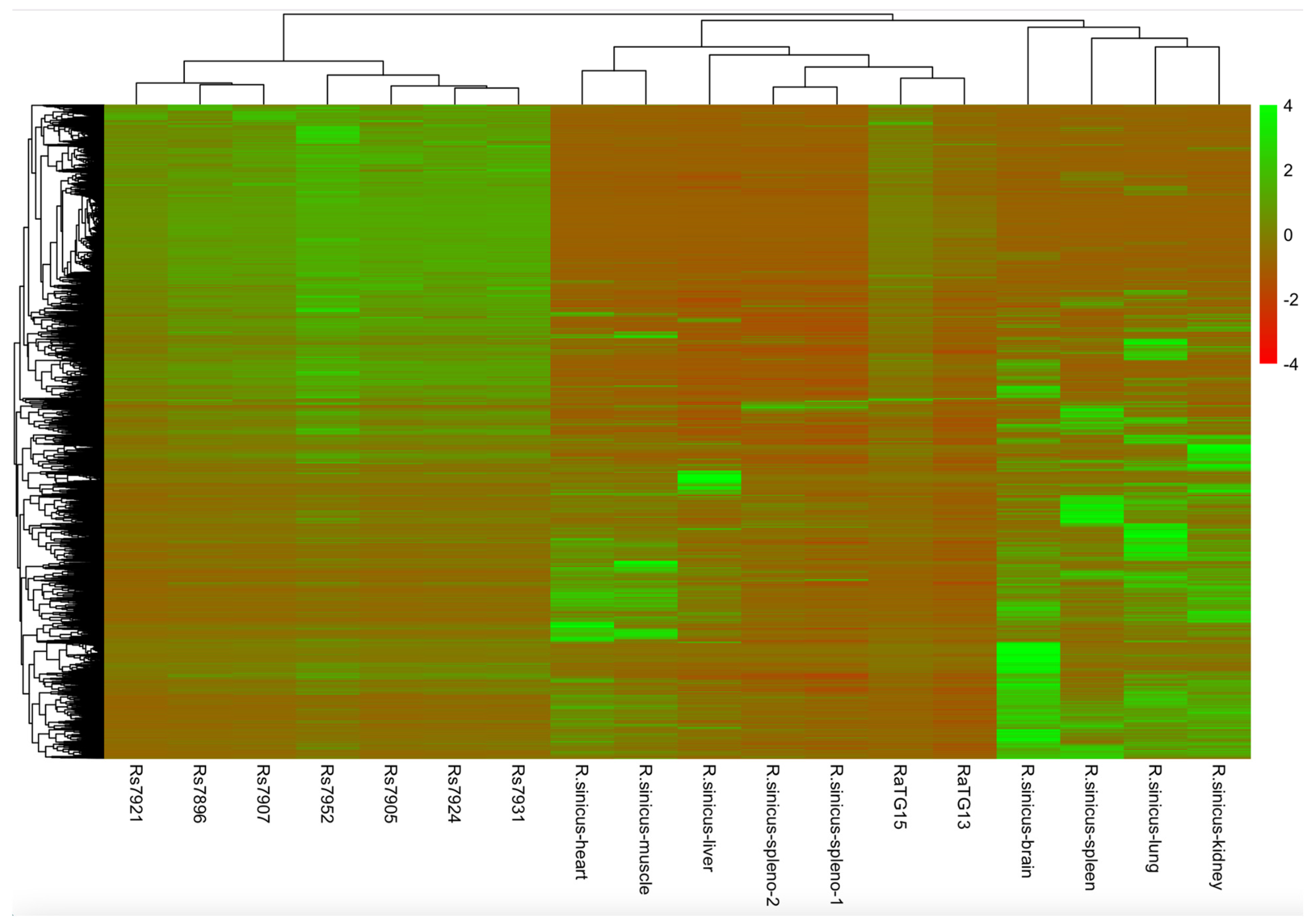

4.9. Transcriptome Comparison

4.10. GO Enrichment Analysis

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holmes, E.C.; Goldstein, S.A.; Rasmussen, A.L.; Robertson, D.L.; Crits-Christoph, A.; Wertheim, J.O.; Anthony, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; Boni, M.F.; Doherty, P.C.; et al. The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review. Cell 2021, 184, 4848–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirotkin, K.; Sirotkin, D. Might SARS-CoV-2 Have Arisen via Serial Passage through an Animal Host or Cell Culture?: A potential explanation for much of the novel coronavirus’ distinctive genome. Bioessays 2020, 42, e2000091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segreto, R.; Deigin, Y. The genetic structure of SARS-CoV-2 does not rule out a laboratory origin: SARS-COV-2 chimeric structure and furin cleavage site might be the result of genetic manipulation. Bioessays 2021, 43, e2000240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-L.; Wang, J.-L.; Ma, X.-H.; Sun, X.-M.; Li, J.-S.; Yang, X.-F.; Shi, W.-F.; Duan, Z.-J. A novel SARS-CoV-2 related coronavirus with complex recombination isolated from bats in Yunnan province, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaune, D.; Hul, V.; Karlsson, E.A.; Hassanin, A.; Ou, T.P.; Baidaliuk, A.; Gámbaro, F.; Prot, M.; Tan Tu, V.; Chea, S.; et al. A novel SARS-CoV-2 related coronavirus in bats from Cambodia. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ji, J.; Chen, X.; Bi, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Hu, T.; Song, H.; Zhao, R.; Chen, Y.; et al. Identification of novel bat coronaviruses sheds light on the evolutionary origins of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses. Cell 2021, 184, 4380–4391.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmam, S.; Vongphayloth, K.; Baquero, E.; Munier, S.; Bonomi, M.; Regnault, B.; Douangboubpha, B.; Karami, Y.; Chrétien, D.; Sanamxay, D.; et al. Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells. Nature 2022, 604, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, A.; Rambaud, O. Retracing Phylogenetic, Host and Geographic Origins of Coronaviruses with Coloured Genomic Bootstrap Barcodes: SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 as Case Studies. Viruses 2023, 15, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. Discovery of a novel coronavirus associated with the recent pneumonia outbreak in humans and its potential bat origin. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.-Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Hu, B.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Zhou, J.-H.; Luo, C.-M.; Yang, X.-L.; Wu, L.-J.; et al. Coexistence of multiple coronaviruses in several bat colonies in an abandoned mineshaft. Virol. Sin. 2016, 31, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segreto, R. Is Considering a Genetic-Manipulation Origin for SARS-CoV-2 a Conspiracy Theory That Must Be Censored? ResearchGate. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340924249_Is_considering_a_genetic-manipulation_origin_for_SARS-CoV-2_a_conspiracy_theory_that_must_be_censored (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Rahalkar, M.C.; Bahulikar, R.A. Lethal Pneumonia Cases in Mojiang Miners (2012) and the Mineshaft Could Provide Important Clues to the Origin of SARS-CoV-2. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 581569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. Addendum: A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 588, E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L. The Analysis of Six Patients with Severe Pneumonia Caused by Unknown Viruses. Ph.D. Thesis, Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. Novel Virus Discovery in Bat and the Exploration of Receptor of Bat Coronavirus HKU9. Ph.D. Thesis, National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rahalkar, M.; Bahulikar, R. The anomalous nature of the fecal swab data, receptor binding domain and other questions in RaTG13 genome. Preprints 2020, 2020080205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Chen, S. Major concerns on the identification of bat Coronavirus strain RaTG13 and quality of related Nature paper. Preprints 2020, 2020060044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, M.; Ahmad, S.; Gupta, C.; Sethi, T. De-novo assembly of RaTG13 genome reveals inconsistencies further obscuring SARS-CoV-2 origins. Preprints 2020, 2020080595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deigin, Y.; Segreto, R. SARS-CoV-2’s claimed natural origin is undermined by issues with genome sequences of its relative strains: Coronavirus sequences RaTG13, MP789 and RmYN02 raise multiple questions to be critically addressed by the scientific community. Bioessays 2021, 43, e2100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostickson, B.; Ghannam, Y. 2. INVESTIGATION OF RaTG13 AND THE 7896 CLADE. 2021, Unpublished. Available online: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.22382.33607 (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Zhang, D. Anomalies in BatCoV/RaTG13 Sequencing and Provenance; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Y. Geographic Evolution of Bat SARS-Related Coronaviruses; Shi, Z., Jie, C., Eds.; Wuhan Institute of Virology: Wuhan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Fujiwara, H.; Zajac, C.; Sandford, E.; Reddy, P.; Choi, S.W.; Tewari, M. A Pipeline for Faecal Host DNA Analysis by Absolute Quantification of LINE-1 and Mitochondrial Genomic Elements Using ddPCR. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, X.-L.; Anderson, D.E.; Shi, Z.-L.; Wang, L.-F.; Zhou, P. Discovery of Bat Coronaviruses through Surveillance and Probe Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing. mSphere 2020, 5, e00807-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, Y.; Shen, X.; Goh, G.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, J.; Wang, L.-F.; Shi, Z.-L.; Zhou, P. Dampened STING-Dependent Interferon Activation in Bats. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 297–301.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briese, T.; Kapoor, A.; Mishra, N.; Jain, K.; Kumar, A.; Jabado, O.J.; Lipkin, W.I. Virome Capture Sequencing Enables Sensitive Viral Diagnosis and Comprehensive Virome Analysis. mBio 2015, 6, e01491-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Hu, B.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Li, A.; Geng, R.; Lin, H.-F.; Yang, X.-L.; et al. Identification of a novel lineage bat SARS-related coronaviruses that use bat ACE2 receptor. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Hartmann, M.; Eriksson, K.M.; Pal, C.; Thorell, K.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Nilsson, R.H. METAXA2: Improved identification and taxonomic classification of small and large subunit rRNA in metagenomic data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2015, 15, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; He, C.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Melançon, C.E. A computational toolset for rapid identification of SARS-CoV-2, other viruses and microorganisms from sequencing data. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanning-NGS-Datasets-for-Mitochondrial-and-Coronavirus-Contaminants. Available online: https://github.com/semassey/Scanning-NGS-datasets-for-mitochondrial-and-coronavirus-contaminants (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Duong, V.; Lim, X.F.; Hul, V.; Chawla, T.; Keatts, L.; Goldstein, T.; Hassanin, A.; Tu, V.T.; Buchy, P.; et al. Presence of Recombinant Bat Coronavirus GCCDC1 in Cambodian Bats. Viruses 2022, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Choudhury, B.; Dayanandan, S.; Khan, M.L. Molecular Genetics and Genomics Tools in Biodiversity Conservation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Applied Research Press. MUSCLE: A Multiple Sequence Alignment Method with Reduced Time and Space Complexity; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tavaré, S. Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. Lect. Math. Life Sci. 1986, 17, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike, H. Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle. Sel. Pap. Hirotugu Akaike 1998, 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, D.; Huang, Z.; Pippel, M.; Hughes, G.M.; Lavrichenko, K.; Devanna, P.; Winkler, S.; Jermiin, L.S.; Skirmuntt, E.C.; Katzourakis, A.; et al. Six reference-quality genomes reveal evolution of bat adaptations. Nature 2020, 583, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolberg, L.; Raudvere, U.; Kuzmin, I.; Adler, P.; Vilo, J.; Peterson, H. g:Profiler-interoperable web service for functional enrichment analysis and gene identifier mapping (2023 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W207–W212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gprofiler. Available online: https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/gost (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Massey, S.E. Comparative Microbial Genomics and Forensics. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, P.; Scott, K.P.; Duncan, S.H.; Flint, H.J. Understanding the effects of diet on bacterial metabolism in the large intestine. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 102, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Péré-Védrenne, C.; Flahou, B.; Loke, M.F.; Ménard, A.; Vadivelu, J. Other Helicobacters, gastric and gut microbiota. Helicobacter 2017, 22 (Suppl. S1), e12407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.F.; Lindberg, M.; Jakobsson, H.; Bäckhed, F.; Nyrén, P.; Engstrand, L. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleifer, K.H.; Kloos, W.E.; Kocur, M. The genus Micrococcus. In The Prokaryotes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, E.S.; Bittinger, K.; Esipova, T.V.; Hou, L.; Chau, L.; Jiang, J.; Mesaros, C.; Lund, P.J.; Liang, X.; FitzGerald, G.A.; et al. Microbes vs. chemistry in the origin of the anaerobic gut lumen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4170–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodkin, A. The Family Peptostreptococcaceae in the Prokaryotes; Rosenberg, E., DeLOng, E.F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., Thompson, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- DeLong, E.F.; Lory, S.; Stackebrandt, E.; Thompson, F. The Prokaryotes: Firmicutes and Tenericutes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.; Zhang, K.; Ma, X.; He, P. Clostridium species as probiotics: Potentials and challenges. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latinne, A.; Hu, B.; Olival, K.J.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Chmura, A.A.; Field, H.E.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Epstein, J.H.; et al. Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.-Y.; Li, J.-L.; Yang, X.-L.; Chmura, A.A.; Zhu, G.; Epstein, J.H.; Mazet, J.K.; Hu, B.; Zhang, W.; Peng, C.; et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2013, 503, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ayeh, S.K.; Chidambaram, V.; Karakousis, P.C. Modes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and evidence for preventive behavioral interventions. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.; Kuhnert, P.; Nørskov-Lauritsen, N.; Planet, P.J.; Bisgaard, M. The Family Pasteurellaceae. In The Prokaryotes: Gammaproteobacteria; Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E.F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., Thompson, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 535–564. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, D.L.; Geme, J.W. The Genus Haemophilus. In The Prokaryotes: A Handbook on the Biology of Bacteria Volume 6: Proteobacteria: Gamma Subclass; Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.-H., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1034–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Dewhirst, F.E.; Chen, T.; Izard, J.; Paster, B.J.; Tanner, A.C.R.; Yu, W.-H.; Lakshmanan, A.; Wade, W.G. The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 5002–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgarel, M.; Noël, V.; Pfukenyi, D.; Michaux, J.; André, A.; Becquart, P.; Cerqueira, F.; Barrachina, C.; Boué, V.; Talignani, L.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing on Insectivorous Bat Guano: An Accurate Tool to Identify Arthropod Viruses of Potential Agricultural Concern. Viruses 2019, 11, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio, D.; Cai, J.J. Systematic determination of the mitochondrial proportion in human and mice tissues for single-cell RNA-sequencing data quality control. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, W.; Mao, X. The complete mitochondrial genome of Rhinolophus affinis himalayanus. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2021, 6, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ith, S.; Bumrungsri, S.; Furey, N.M.; Bates, P.J.; Wonglapsuwan, M.; Khan, F.A.A.; Thong, V.D.; Soisook, P.; Satasook, C.; Thomas, N.M. Taxonomic implications of geographical variation in Rhinolophus affinis (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae) in mainland Southeast Asia. Zool. Stud. 2015, 54, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Shen, Y.; Sordoni, A.; Courville, A.; O’donnell, T.J. Recursive Top-Down Production for Sentence Generation with Latent Trees. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Rossiter, S.J. Genome-wide data reveal discordant mitonuclear introgression in the intermediate horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus affinis). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2020, 150, 106886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chornelia, A.; Lu, J.; Hughes, A.C. How to accurately delineate morphologically conserved taxa and diagnose their phenotypic disparities: Species delimitation in cryptic Rhinolophidae (Chiroptera). Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 854509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffberg, S.; Jacobs, D.S.; Mackie, I.J.; Matthee, C.A. Molecular phylogenetics and historical biogeography of Rhinolophus bats. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2010, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Jiang, T.; Huang, X.; Feng, J. Patterns of sexual size dimorphism in horseshoe bats: Testing Rensch’s rule and potential causes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.G.; Zhu, G.J.; Zhang, S.; Rossiter, S.J. Pleistocene climatic cycling drives intra-specific diversification in the intermediate horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus affinis) in Southern China. Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 2754–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockendon, N.F.; O’Connell, L.A.; Bush, S.J.; Monzón-Sandoval, J.; Barnes, H.; Székely, T.; Hofmann, H.A.; Dorus, S.; Urrutia, A.O. Optimization of next-generation sequencing transcriptome annotation for species lacking sequenced genomes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2016, 16, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierszenbaum, A.L.; Rivkin, E.; Tres, L.L. Acroplaxome, an F-actin-keratin-containing plate, anchors the acrosome to the nucleus during shaping of the spermatid head. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 4628–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, J.; Ortiz, Á.; Bejarano, I.; Lozano, G.M.; Monllor, F.; García, J.F.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Pariente, J.A. Melatonin protects human spermatozoa from apoptosis via melatonin receptor- and extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated pathways. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 2290–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milardi, D.; Colussi, C.; Grande, G.; Vincenzoni, F.; Pierconti, F.; Mancini, F.; Baroni, S.; Castagnola, M.; Marana, R.; Pontecorvi, A. Olfactory Receptors in Semen and in the Male Tract: From Proteome to Proteins. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.R.; Mangels, R.; Dean, M.D. The molecular basis and reproductive function(s) of copulatory plugs. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2016, 83, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.K.; Mori, T.; Uchida, T.A. Studies on the vaginal plug of the Japanese greater horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum nippon. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1983, 68, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H. Vaginal plug formation and release in female hibernating Korean greater horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum korai (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae) during the annual reproductive cycle. Zoomorphology 2020, 139, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, S.J.; Jones, G.; Ransome, R.D.; Barratt, E.M. Genetic variation and population structure in the endangered greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, G.S.; McCracken, G.F. Bats and balls: Sexual selection and sperm competition in the Chiroptera. In Bat Ecology; Kunz, T.H., Fenton, M.B., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006; pp. 128–155. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, T.; Oh, Y.K.; Uchida, T. Sperm Storage in the Oviduct of the Japanese Greater Horseshoe Bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum nippon. J. Fac. Agric. Kyushu Univ. 1982, 27, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanders, J.; Jones, G. Roost Use, Ranging Behavior, and Diet of Greater Horseshoe Bats (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) Using a Transitional Roost. J. Mammal. 2009, 90, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgin, C. Rhinolophidae. In Handbook of the Mammals of the World—Volume 9; Wilson, D.E., Mittermeier, R.A., Eds.; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; pp. 280–332. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoni, M.; Pietrokovski, S. The landscape of sex-differential transcriptome and its consequent selection in human adults. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boskey, E.R.; Telsch, K.M.; Whaley, K.J.; Moench, T.R.; Cone, R.A. Acid production by vaginal flora in vitro is consistent with the rate and extent of vaginal acidification. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 5170–5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boskey, E.R.; Cone, R.A.; Whaley, K.J.; Moench, T.R. Origins of vaginal acidity: High D/L lactate ratio is consistent with bacteria being the primary source. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 16, 1809–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, S.E. SARS-CoV-2’s closest relative, RaTG13, was generated from a bat transcriptome not a fecal swab: Implications for the origin of COVID-19. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.09469. [Google Scholar]

- Bruttel, V.; Washburne, A.; VanDongen, A. Endonuclease fingerprint indicates a synthetic origin of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; He, G.; Sharp, A.K.; Wang, X.; Brown, A.M.; Michalak, P.; Weger-Lucarelli, J. A selective sweep in the Spike gene has driven SARS-CoV-2 human adaptation. Cell 2021, 184, 4392–4400.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cereghino, C.; Michalak, K.; DiGiuseppe, S.; Guerra, J.; Yu, D.; Faraji, A.; Sharp, A.K.; Brown, A.M.; Kang, L.; Weger-Lucarelli, L.; et al. Evolution at Spike protein position 519 in SARS-CoV-2 facilitated adaptation to humans. npj Viruses 2024, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Total Number of (Forward) Reads in Dataset | Total Number of SSU rRNA Sequences (% of Total Reads in Brackets) | Number of Bacterial SSU rRNA Sequences (% of Total rRNA Sequences in Brackets) | Number of Eukaryotic SSU rRNA Sequences (% of Total SSU rRNA Sequences in Brackets) | Ratio of Eukaryotic to Bacterial SSU rRNA Sequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RaTG13 | 11,604,666 | 208,776 (1.8%) | 21,548 (10.3%) | 178,804 (85.6%) | 8.3:1 |

| BtRhCoV-HKU2r anal swab | 11,924,182 | 2,470,567 (20.7%) | 2,085,824 (84.4%) | 384,023 (15.5%) | 1:5.4 |

| Splenocyte 1 transcriptome | 4,764,112 | 1,306,781 (27.4%) | 13,959 (1.1%) | 1,238,388 (94.8%) | 88.7:1 |

| Ebola oral swab | 1,000,000 | 1,341,026 (13.4%) | 283,350 (21.1%) | 1,050,512 (78.3%) | 3.7:1 |

| Taxonomic Group | RaTG13 Sample | BtRhCoV-HKU2r anal Swab | Splenocyte 1 Transcriptome | Ebola Oral Swab |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||||

| Enterobacteriaceae | 18.1% (3891) | 7.4% (154,498) | 90.7% (12,667) | 2.4% (6860) |

| Enterobacteriaceae, Escherichia | 4.9% (1,046) | 4.8% (100,567) | 74.1% (10,340) | 0.003% (9) |

| Mycoplasma | 0.07% (15) | 0.04% (869) | 0.1% (18) | 0.005% (14) |

| Helicobacter | 0.005% (1) | 0.4% (8490) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Bacillus | 0.004% (8) | 0.4% (8214) | 0.01% (1) | 5.2% (14,662) |

| Peptostreptococcaceae | 0.07% (16) | 21.2% (442,050) | 0% (0) | 0.0007% (2) |

| Enterococcus | 6.7% (1453) | 6.3% (132,235) | 0.2% (30) | 2.4% (6828) |

| Lachnospiraceae | 0.7% (146) | 6.2% (128,630) | 0.01% (1) | 0.08% (221) |

| Clostridium | 0.7% (141) | 47.8% (997,409) | 0% (0) | 0.01% (31) |

| Lactococcus | 64.0% (13,780) | 0.07% (1532) | 0% (0) | 0.06% (162) |

| Lactobacillus | 0.02% (5) | 0.0009% (18) | 0.01% (1) | 0.005% (13) |

| Micrococcus | 4.5% (960) | 0% (0) | 0.08% (11) | 0% (0) |

| Pasteurellaceae | 0.03% (7) | 3.1% (64,468) | 0% (0) | 51.3% (145,394) |

| Pasteurellaceae, Haemophilus | 0.01% (2) | 0.02% (511) | 0% (0) | 4.4% (12,383) |

| Gemella | 0% (0) | 0.005% (106) | 0.02% (3) | 0.3% (742) |

| Eukaryota | ||||

| Arthropoda | 0.02% (35) | 0.01% (36) | 0.01% (157) | 0.4% (4005) |

| Arthropoda, Insecta | 0.02% (29) | 0.008% (30) | 0.009% (113) | 0.1% (1348) |

| Fungi | 0.2% (302) | 0.002% (6) | 0.02% (261) | 0.02% (186) |

| Viridiplantae | 0.1% (214) | 0.05% (198) | 0.001% (13) | 0.002% (22) |

| Sample | Total Number of (Forward) Reads in Dataset | Total Number of rRNA Sequences (% of Total Sequences in Brackets) | Number of Bacterial rRNA Sequences (% of Total rRNA Sequences in Brackets) | Number of Eukaryotic rRNA Sequences (% of Total rRNA Sequences in Brackets) | Ratio of Eukaryotic to Bacterial rRNA Sequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RaTG15 (Ra7909) | 57,967,763 | 7,582,328 (13.1%) | 15,497 (0.2%) | 7,364,952 (97.1%) | 475.3:1 |

| Rs7896 | 33,095,822 | 2,334,500 (7.1%) | 3599 (0.2%) | 2,273,798 (97.4%) | 631.8:1 |

| Rs7905 | 34,515,819 | 1,472,236 (4.3%) | 45,803 (3.1%) | 1,387,437 (94.2%) | 30.3:1 |

| Rs7907 | 43,686,062 | 3,321,723 (7.6%) | 111,111 (3.3%) | 3,239,588 (97.5%) | 29.2:1 |

| Rs7921 | 100,971,808 | 12,814,436 (12.7%) | 2,200,755 (17.2%) | 10,312,025 (80.5%) | 4.7:1 |

| Rs7924 | 45,210,219 | 1,908,141 (4.2%) | 108,044 (5.7%) | 1,719,177 (90.1%) | 15.9:1 |

| Rs7931 | 51,086,664 | 2,565,395 (5.0%) | 319,175 (12.4%) | 2,195,238 (85.6%) | 6.9:1 |

| Rs7952 | 40,979,989 | 372,805 (0.9%) | 2720 (0.7%) | 342,244 (91.8%) | 125.8 |

| Sample Dataset SRA Accession Number (Number of Reads in Brackets) | Coronavirus Genome (NCBI Accession Number in Brackets) | Number of Reads Mapped to Respective Coronavirus Genome | Proportion of Reads Mapping to Coronavirus Compared to Total Number of Reads |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRR11085797 (23209332) | RaTG13 (MN996532) | 1669 | 7.2 × 10−5 |

| SRR11085736 (23848364) | BtRhCoV-HKU2r (MN611522) | 886 | 3.7 × 10−5 |

| SRR11085735 (8032494) | BtHpCoV-HKU10-related (MN611523) | 7030 | 8.8 × 10−4 |

| SRR11085733 (R. larvatus) (27083324) | BtHiCoV-CHB25 (MN611525) | 1,035,522 | 3.8 × 10−2 |

| SRR11085741 (24828142) | BtRaCoV-229E-related (MN611517) | 99,776 | 4.0 × 10−3 |

| SRR11085734 (19171950) | BtMiCoV-1-related (MN611524) | 581 | 3.0 × 10−5 |

| SRR11085740 (19562848) | BtMiCoV-HKU8-related (MN611518) | 2817 | 1.4 × 10−4 |

| SRR11085737 (23088962) | BtScCoV-512-related (MN611521) | 142,646 | 6.2 × 10−3 |

| SRR11085738 (29134128) | BtPiCoV-HKU5-related (MN611520) | 1,437,700 | 4.9 × 10−2 |

| SRR11085739 (9589348) | BtTyCoV-HKU4-related (MN611519) | 2778 | 2.9 × 10−4 |

| Species | Mitochondrial Genome NCBI Accession Number | Percent of Mitochondrial Genome Covered (Number of Reads Mapped in Brackets) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RaTG13 | BtRhCoV-HKU2r Anal Swab | Splenocyte Transcriptome | ||

| R. affinis | NC_053269.1 | 97.2% (75,335) | 14.9% (6278) | 32.2% (88,220) |

| R. sinicus | KP257597.1 | 40.4% (18,017) | 29.8% (10,019) | 94.5% (170,591) |

| Mouse | NC_005089.1 | 6.3% (111) | 1.6% (18) | 6.0% (1755) |

| Human | NC_012920.1 | 3.6% (26) | 9.4% (23) | 40.5% (91) |

| Pig | NC_012095.1 | 6.6% (1606) | 4.2% (155) | 5.2% (2238) |

| Black foot ferret (Mustela nigripes) | NC_024942.1 | 6.6% (1537) | 3.0% (61) | 5.2% (1383) |

| Malaysian pangolin (Manis javanica) | NC_026781.1 | 4.9% (88) | 2.2% (32) | 3.5% (1254) |

| Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) | NC_001913.1 | 5.1% (92) | 1.4% (16) | 2.7% (1529) |

| Asian Palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus) | MG200264.1 | 5.6% (1836) | 4.3% (185) | 4.4% (5258) |

| Chinese tree shrew (Tupaia chinensis) | AF217811 | 4.2% (655) | 2.7% (14) | 2.9% (4117) |

| Species | Genome Assembly NCBI Accession Number | % of RaTG13 Sample Reads Mapped to Genome | % of BtRhCoV-HKU2r anal Swab Sample Reads Mapped to Genome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greater horseshoe bat (R. ferrumequinum) | GCA_004115265.3 | 87.5% | 2.6% |

| Human | GCA_000001405.28 | 64.3% | 7.4% |

| Mouse | GCA_000001635.9 | 62.2% | 6.6% |

| Green monkey | GCA_000409795.2 | 51.5% | 7.5% |

| Pig | GCA_000003025.6 Sscrofa11.1 | 62.5% | 7.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Massey, S.E. Forensic Genomic Analysis Determines That RaTG13 Was Likely Generated from a Bat Mating Plug. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 15, 1784-1805. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres15030119

Massey SE. Forensic Genomic Analysis Determines That RaTG13 Was Likely Generated from a Bat Mating Plug. Microbiology Research. 2024; 15(3):1784-1805. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres15030119

Chicago/Turabian StyleMassey, Steven E. 2024. "Forensic Genomic Analysis Determines That RaTG13 Was Likely Generated from a Bat Mating Plug" Microbiology Research 15, no. 3: 1784-1805. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres15030119

APA StyleMassey, S. E. (2024). Forensic Genomic Analysis Determines That RaTG13 Was Likely Generated from a Bat Mating Plug. Microbiology Research, 15(3), 1784-1805. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres15030119