An Unusual Case of Listeria monocytogenes-Associated Rhombencephalitis Complicated by Brain Abscesses in Italy, 2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

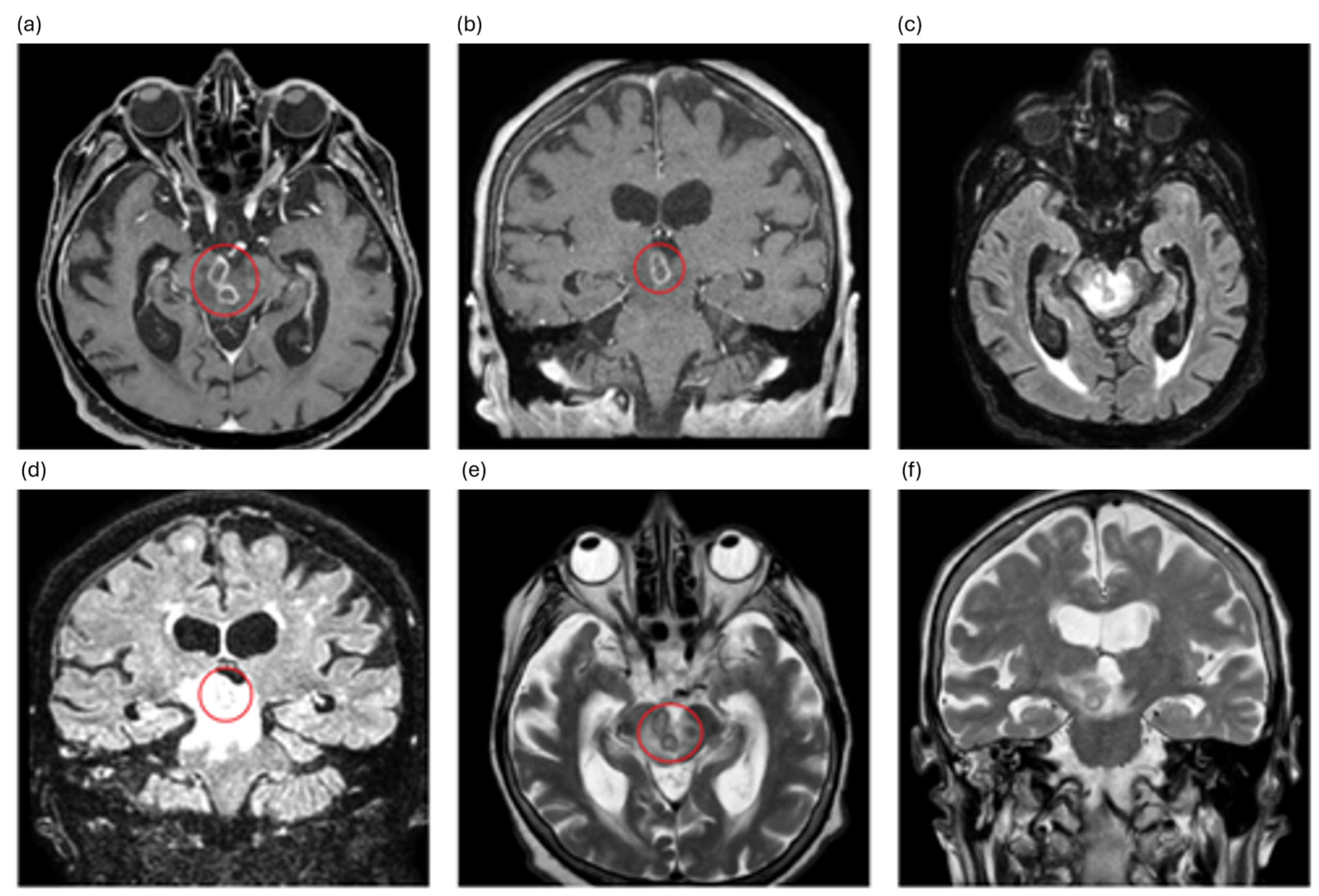

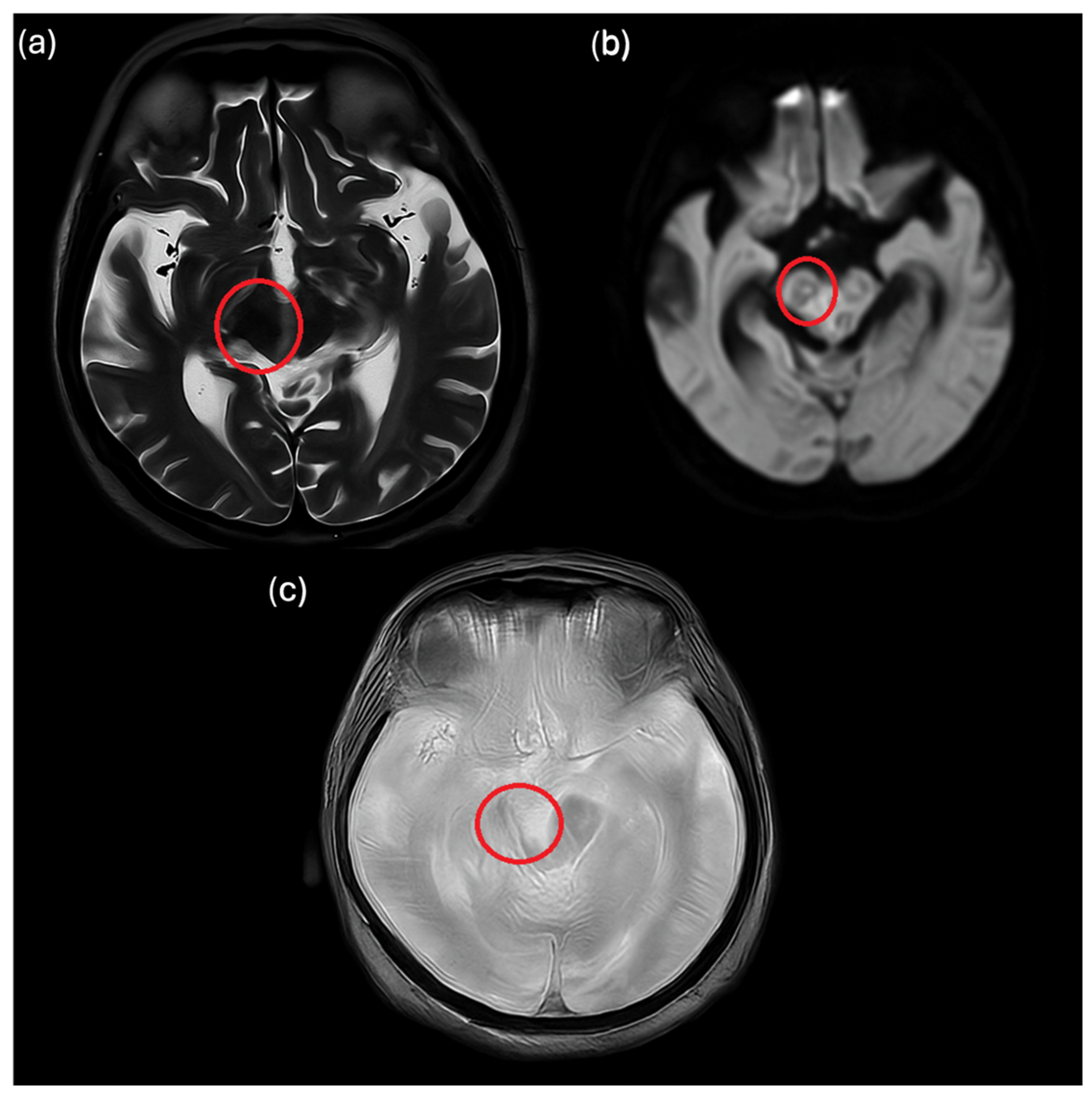

2. Case Description

3. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koopmans, M.M.; Brouwer, M.C.; Vázquez-Boland, J.A.; van de Beek, D. Human Listeriosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 36, e0006019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disson, O.; Lecuit, M. Targeting of the central nervous system by Listeria monocytogenes. Virulence 2012, 3, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiri, B.; Priante, G.; Saraca, L.M.; Martella, L.A.; Cappanera, S.; Francisci, D. Listeria monocytogenes Brain Abscess: Controversial Issues for the Treatment—Two Cases and Literature Review. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2018, 2018, e6549496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckburg, P.B.; Montoya, J.G.; Vosti, K.L. Brain Abscess due to Listeria monocytogenes: Five Cases and a Review of the Literature. Medicine 2001, 80, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, B.H.; de Melo, T.G.; da Silva, A.F.F.; Lopes, J.T.; Ducci, R.D.; Carraro Junior, H.; Ducroquet, M.A.; França, J.C.B. Brain abscesses caused by Listeria monocytogenes in a patient with myasthenia gravis—Case report and systematic review. Infez Med. 2023, 31, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudy, P.; Vavasseur, C.; Boumaza, X.; Bryant, S.; Fillaux, J.; Iriart, X.; Grare, M.; Beltaïfa, M.Y.; Roux, F.-E.; Bonneville, F.; et al. Brain abscess caused by Listeria monocytogenes and Toxoplasma gondii. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragomir, R.M.; Mattner, O.; Hagan, V.; Swerdloff, M.A. Listeria monocytogenes Brain Abscess Presenting With Stroke-Like Symptoms: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e52216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraco, P.; Incandela, F.; Stallone, F.; Alaimo, F.; Geraci, L.; Bencivinni, F.; Tona, G.; Gagliardo, C. Hemorragic presentation of Listeria Monocytogenes rhombencephalic abscess. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 27, e28–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Xu, L.; Tao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, Z. Brain abscess due to Listeria monocytogenes: A case report and literature review. Medicine 2021, 100, e26839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yi, Z. Brain abscess caused by Listeria monocytogenes: A case report and literature review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2022, 11, 3356360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility (EUCAST). EUCAST Disk Diffusion Method for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Disk_test_documents/2023_manuals/Manual_v_11.0_EUCAST_Disk_Test_2023.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Ministry of Health. General Directorate of Health Prevention Circular Note on Surveillance and Prevention of Listeriosis (no. 0008252–13/03/2017-DGPRE-DGPRE-P) [In Italian]. Available online: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/0/Listeriosi+-+Prima+Nota+Circolare+Ministero+della+Salute.pdf/6e18fcf8-b7b4-19ff-d6c3-c849899400aa?t=1582305476785 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Moura, A.; Criscuolo, A.; Pouseele, H.; Maury, M.M.; Leclercq, A.; Tarr, C.; Björkman, J.T.; Dallman, T.; Reimer, A.; Enouf, V.; et al. Whole genome-based population biology and epidemiological surveillance of Listeria monocytogenes. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 2, 16185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Pettengill, J.B.; Luo, Y.; Payne, J.; Shpuntoff, A.; Rand, H.; Strain, E. CFSAN SNP Pipeline: An automated method for constructing SNP matrices from next-generation sequence data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2015, 1, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier, C.; Perrodeau, É.; Leclercq, A.; Cazenave, B.; Pilmis, B.; Henry, B.; Lopes, A.; Maury, M.M.; Moura, A.; Goffinet, F.; et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of listeriosis: The MONALISA national prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jubelt, B.; Mihai, C.; Li, T.M.; Veerapaneni, P. Rhombencephalitis/brainstem encephalitis. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2011, 11, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.G.; Trindade, R.A.R.; Faistauer, Â.; Pérez, J.A.; Vedolin, L.M.; Duarte, J.Á. Rhombencephalitis: Pictorial essay. Radiol. Bras. 2016, 49, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crawford, J.R.; Kadom, N.; Santi, M.R.; Mariani, B.; Lavenstein, B.L. Human herpesvirus 6 rhombencephalitis in immunocompetent children. J. Child Neurol. 2007, 22, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Si, Z.; Wei, N.; Cao, D.; Ji, Y.; Kang, Z.; Zhu, J. Next-Generation Sequencing of Cerebrospinal Fluid for the Diagnosis of VZV-Associated Rhombencephalitis. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2023, 22, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoullis, L.; Vaz, V.R.; Kaur, D.; Kakoulli, S.; Panos, G.; Chen, L.H.; Behlau, I. Powassan Virus Infections: A Systematic Review of Published Cases. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlović, D.; Lević, Z.; Dmitrović, R.; Stojsavljević, N.; Janković, S.; Mraković, D.; Bekrić-Pajić, M.; Petrović, R.; Ocić, G. Rombencefalitis kao manifestacija neuroborelioze [Rhombencephalitis as a manifestation of neuroborreliosis]. Glas Srp. Akad. Nauka Med. 1993, 43, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Balducci, C.; Foresti, S.; Ciervo, A.; Mancini, F.; Nastasi, G.; Marzorati, L.; Gori, A.; Ferrarese, C.; Appollonio, I.; Peri, A.M. Primary Whipple disease of the Central Nervous System presenting with rhombencephalitis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 88, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.; Bucelli, R. Reversible Rhombencephalitis in Neuro-Behçet’s Disease. Neurohospitalist 2017, 7, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppens, T.; Van den Bergh, P.; Duprez, T.J.; Jeanjean, A.; De Ridder, F.; Sindic, C.J. Paraneoplastic rhombencephalitis and brachial plexopathy in two cases of amphiphysin auto-immunity. Eur. Neurol. 2006, 55, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas-Alvarez, M.X.; Townsend Ramsett, M.K.; Malekmohammadi, S.; Bergholz, T.M. Evidence of hypervirulence in Listeria monocytogenes clonal complex 14. J. Med Microbiol. 2019, 68, 1677–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gori, M.; Orsani, G.; Ortelli, C.; Scaltriti, E.; Bolzoni, L.; Vezzosi, L.; Bianchi, S.; Fappani, C.; Colzani, D.; Amendola, A.; et al. An Unusual Case of Listeria monocytogenes-Associated Rhombencephalitis Complicated by Brain Abscesses in Italy, 2024. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2026, 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr18010005

Gori M, Orsani G, Ortelli C, Scaltriti E, Bolzoni L, Vezzosi L, Bianchi S, Fappani C, Colzani D, Amendola A, et al. An Unusual Case of Listeria monocytogenes-Associated Rhombencephalitis Complicated by Brain Abscesses in Italy, 2024. Infectious Disease Reports. 2026; 18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr18010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleGori, Maria, Giorgia Orsani, Carlotta Ortelli, Erika Scaltriti, Luca Bolzoni, Luigi Vezzosi, Silvia Bianchi, Clara Fappani, Daniela Colzani, Antonella Amendola, and et al. 2026. "An Unusual Case of Listeria monocytogenes-Associated Rhombencephalitis Complicated by Brain Abscesses in Italy, 2024" Infectious Disease Reports 18, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr18010005

APA StyleGori, M., Orsani, G., Ortelli, C., Scaltriti, E., Bolzoni, L., Vezzosi, L., Bianchi, S., Fappani, C., Colzani, D., Amendola, A., Cereda, D., Marzorati, L., Pongolini, S., & Tanzi, E. (2026). An Unusual Case of Listeria monocytogenes-Associated Rhombencephalitis Complicated by Brain Abscesses in Italy, 2024. Infectious Disease Reports, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr18010005