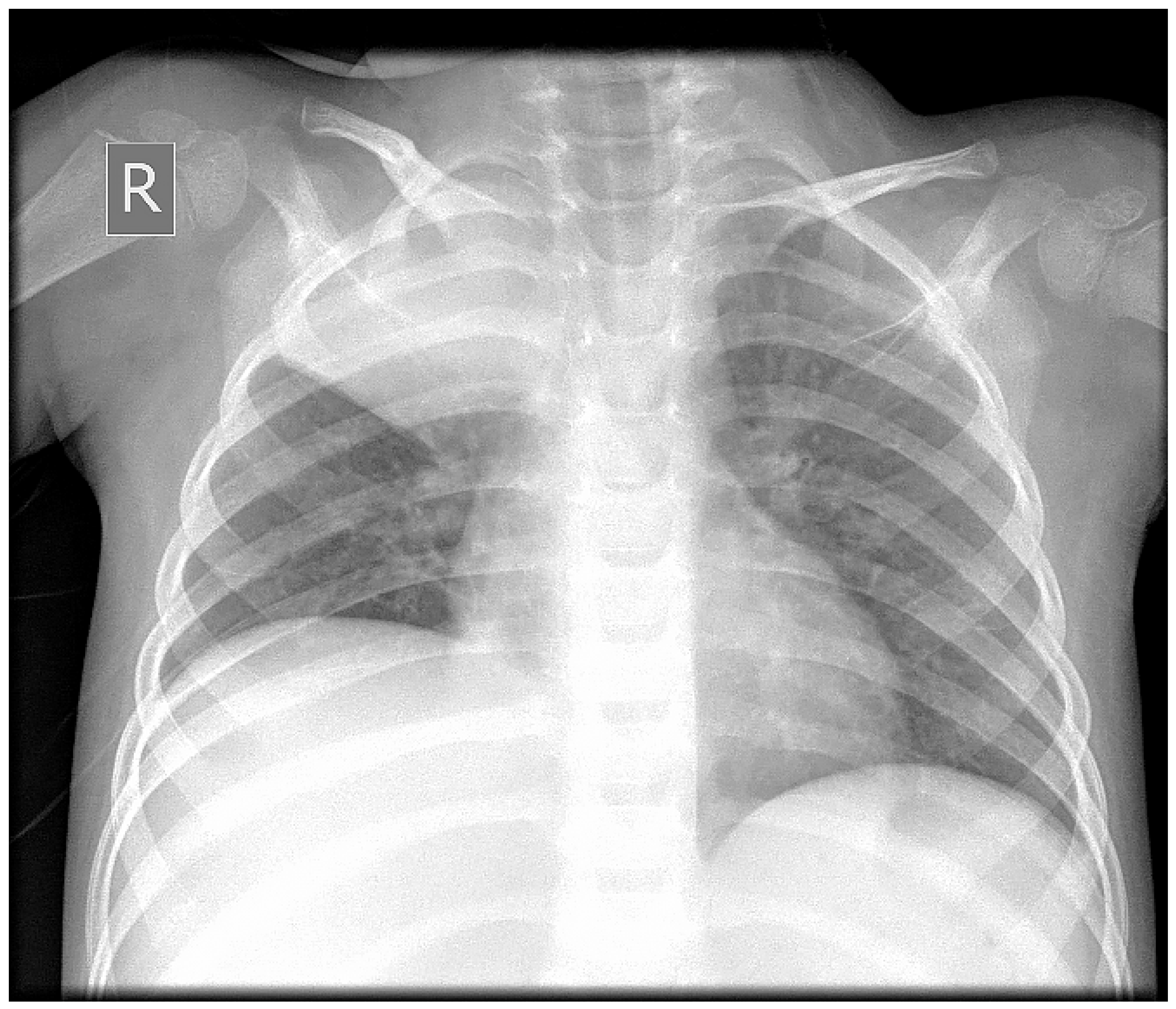

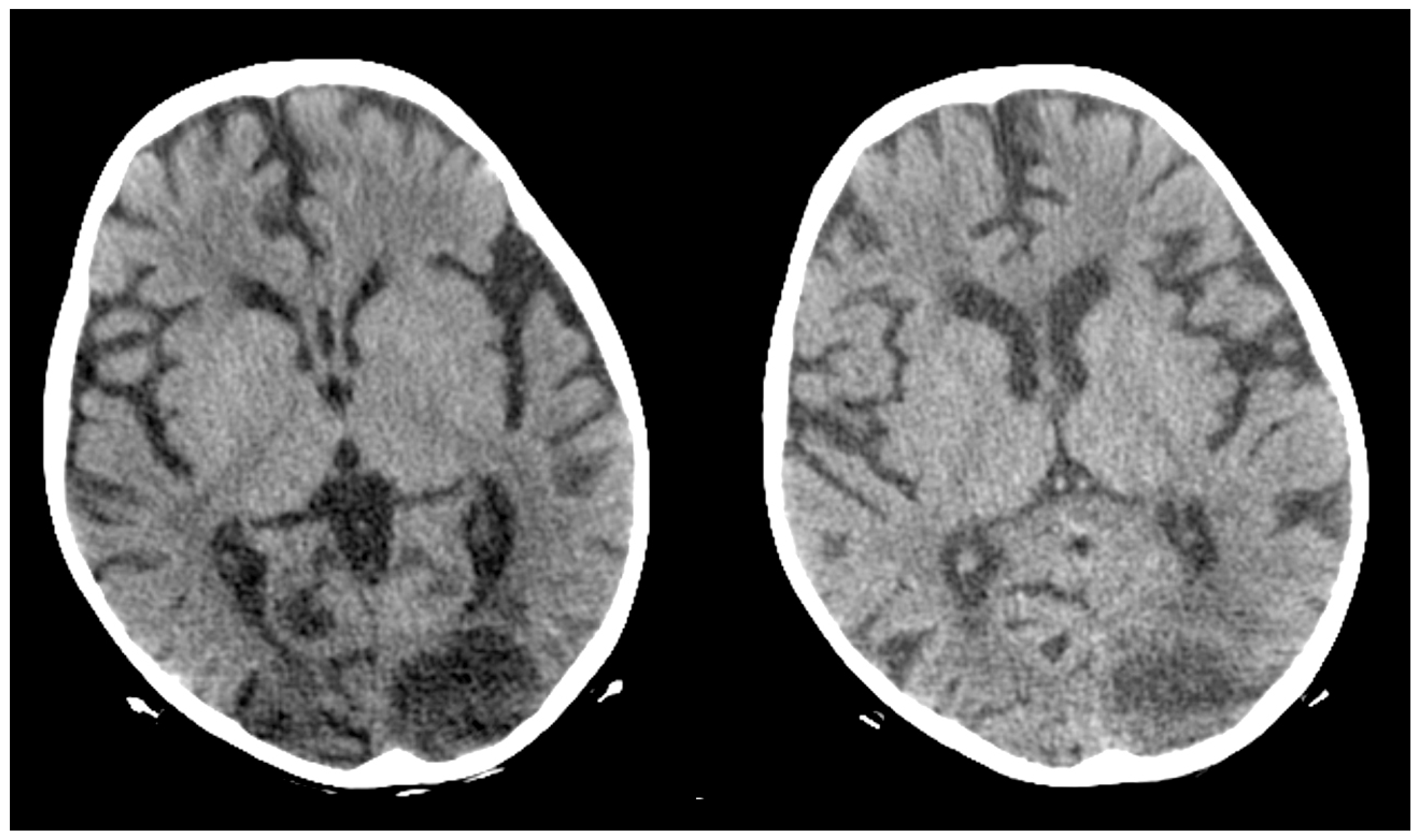

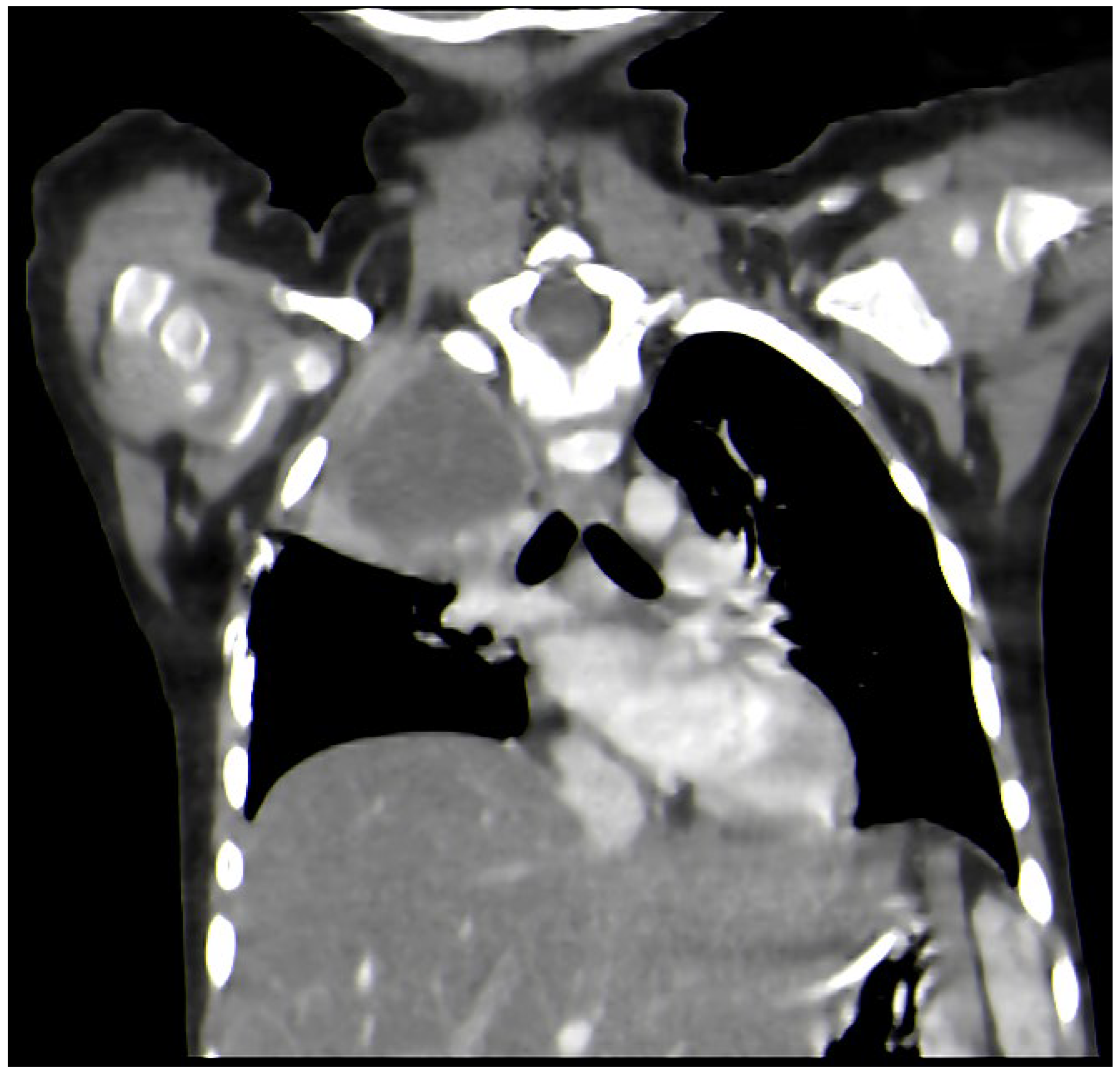

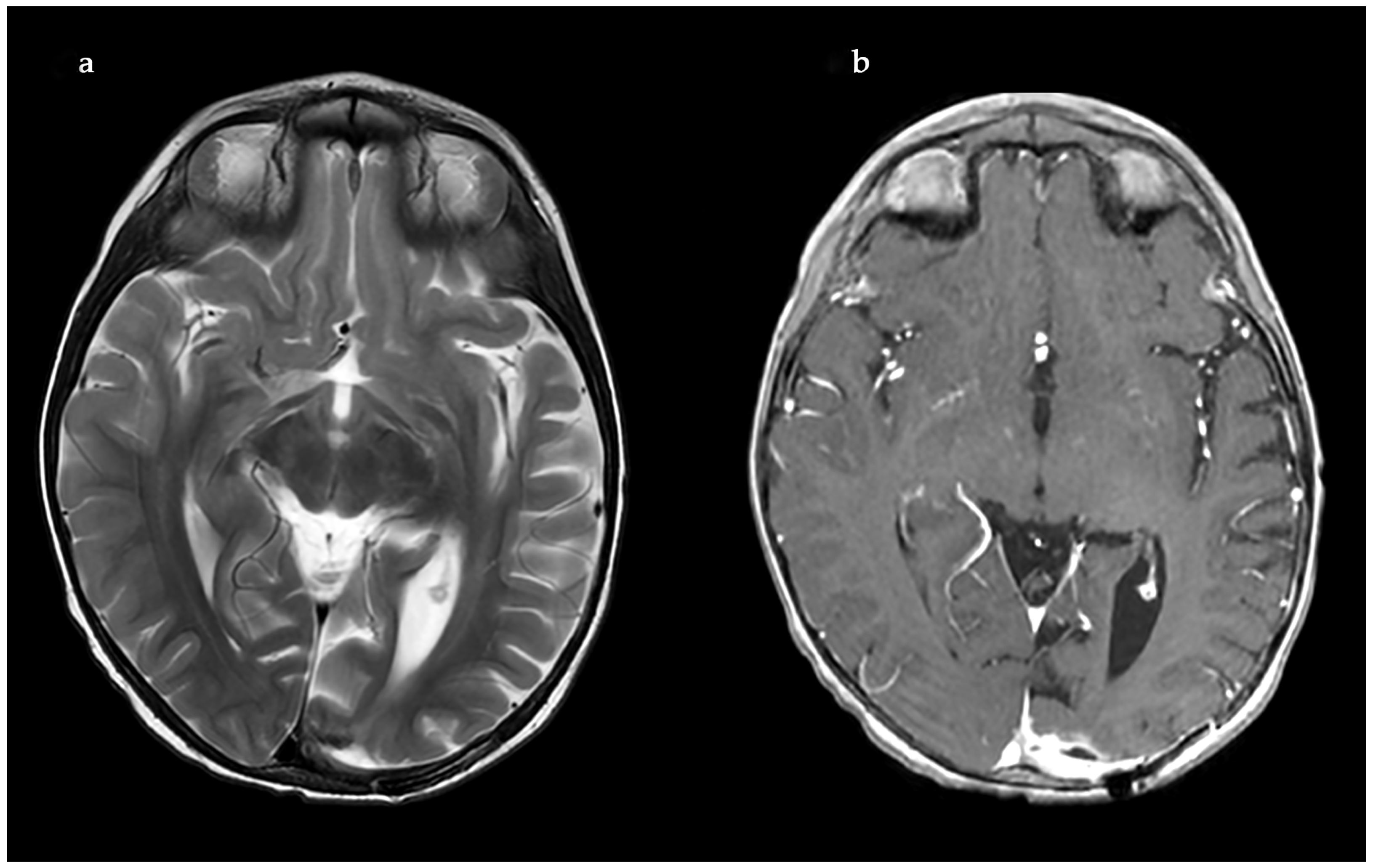

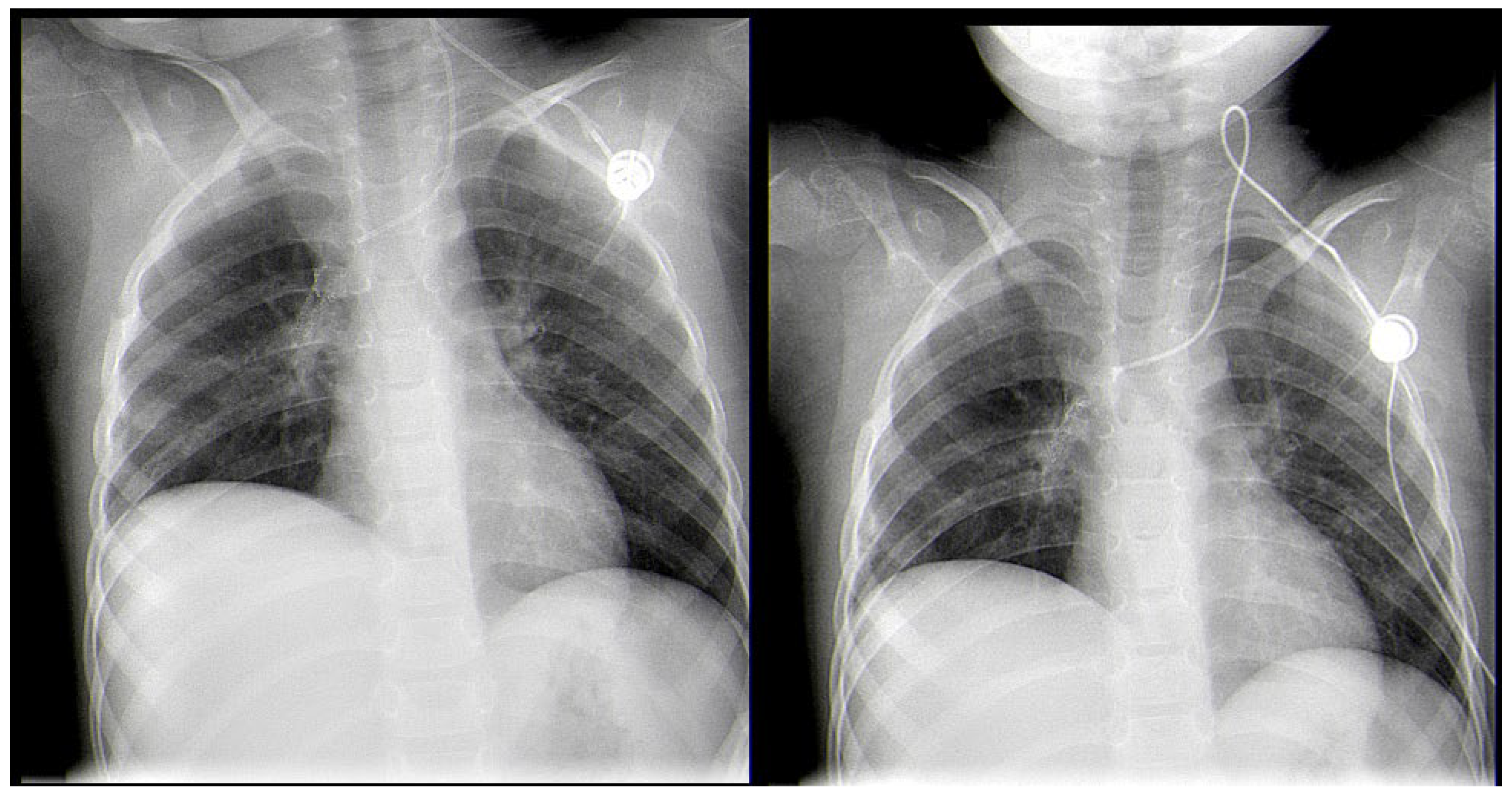

A Rare Case of Rhizomucor pusillus Infection in a 3-Year-Old Child with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Presenting with Lung and Brain Abscesses—Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

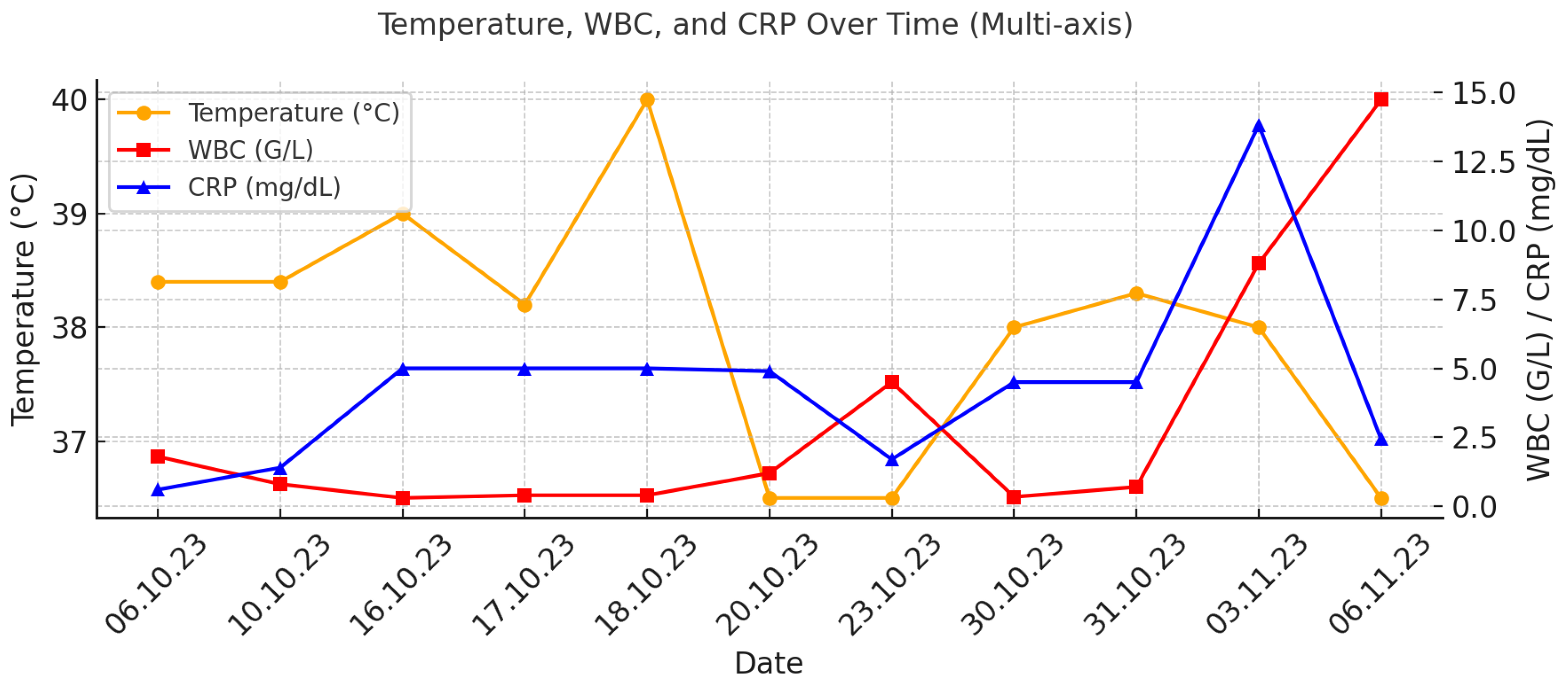

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Toda, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Abe, N.; Hata, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Honjo, G.; Noma, S.; Misaki, T.; Ohno, H. Rhizomucor pusillus infection in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia successfully treated with extensive surgical debridement and long-term liposomal amphotericin B. Tenri Med. Bull. 2018, 21, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, C.A.; Malani, A.N. Zygomycosis: An emerging fungal infection with new options for management. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2007, 9, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribes, J.A.; Vanover-Sams, C.L.; Baker, D.J. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 236–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.Z.; Lewis, R.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Mucormycosis caused by unusual mucormycetes, non-Rhizopus, -Mucor, and -Lichtheimia species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 411–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, M.M.; Zaoutis, T.E.; Buchanan, W.L.; Knudsen, T.A.; Sarkisova, T.A.; Schaufele, R.L.; Sein, M.; Sein, T.; Chiou, C.C.; Chu, J.H.; et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: A review of 929 reported cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 634–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bala, K.; Chander, J.; Handa, U.; Punia, R.S.; Attri, A.K. A prospective study of mucormycosis in north India: Experience from a tertiary care hospital. Med. Mycol. 2015, 53, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, L.; Feng, S. Clinical Features and Treatment Progress of Invasive Mucormycosis in Patients with Hematological Malignancies. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorifard, M.; Sekhavati, E.; Khoo, H.J.; Hazraty, I.; Tabrizi, R. Epidemiology and clinical manifestation of fungal infection related to Mucormycosis in hematologic malignancies. J. Med. Life 2015, 8, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Guinea, J.; Escribano, P.; Vena, A.; Munoz, P.; Martinez-Jimenez, M.D.C.; Padilla, B.; Bouza, E. Increasing incidence of mucormy- cosis in a large Spanish hospital from 2007 to 2015: Epidemiology and microbiological characterization of the isolates. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Azie, N.; Franks, B.; Horn, D.L. Prospective antifungal therapy (PATH) alliance((R)): Focus on mucormycosis. Mycoses 2014, 57, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Kaur, H.; Xess, I.; Michael, J.S.; Savio, J.; Rudramurthy, S.; Singh, R.; Shastri, P.; Umabala, P.; Sardana, R.; et al. A multicentre observational study on the epidemiology, risk factors, management and outcomes of mucormycosis in India. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 944.e9–944.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, R.; Nishimura, S.; Fujimoto, G.; Ainiwaer, D. The disease burden of mucormycosis in Japan: Results from a systematic literature review and retrospective database study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2021, 37, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, K.J.; Daveson, K.; Slavin, M.A.; van Hal, S.J.; Sorrell, T.C.; Lee, A.; Marriott, D.J.; Chapman, B.; Halliday, C.L.; Hajkowicz, K.; et al. Mucormycosis in Australia: Contemporary epidemiology and outcomes. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabritz, J.; Attarbaschi, A.; Tintelnot, K.; Kollmar, N.; Kremens, B.; von Loewenich, F.D.; Schrod, L.; Schuster, F.; Wintergerst, U.; Weig, M.; et al. Mucormycosis in paediatric patients: Demographics, risk factors and outcome of 12 contemporary cases. Mycoses 2011, 54, e785–e788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skiada, A.; Pagano, L.; Groll, A.; Zimmerli, S.; Dupont, B.; Lagrou, K.; Lass-Florl, C.; Bouza, E.; Klimko, N.; Gaustad, P.; et al. Zygomycosis in Europe: Analysis of 230 cases accrued by the registry of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) Working Group on Zygomycosis between 2005 and 2007. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimko, N.; Khostelidi, S.; Shadrivova, O.; Volkova, A.; Popova, M.; Uspenskaya, O.; Shneyder, T.; Bogomolova, T.; Ignatyeva, S.; Zubarovskaya, L.; et al. Contrasts between mucormycosis and aspergillosis in oncohematological patients. Med. Mycol. 2019, 57, S138–S144. [Google Scholar]

- Chamilos, G.; Lewis, R.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Delaying amphotericin B-based frontline therapy significantly increases mortality among patients with hematologic malignancy who have zygomycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthu, V.; Agarwal, R.; Dhooria, S.; Sehgal, I.S.; Prasad, K.T.; Aggarwal, A.N.; Chakrabarti, A. Has the mortality from pulmonary mucormycosis changed over time? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.P.; Chen, S.C.; Kauffman, C.A.; Steinbach, W.J.; Baddley, J.W.; Verweij, P.E.; Clancy, C.J.; Wingard, J.R.; Lockhart, S.R.; Groll, A.H.; et al. Revision and Update of the Consensus Definitions of Invasive Fungal Disease From the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanio, A.; Garcia-Hermoso, D.; Mercier-Delarue, S.; Lanternier, F.; Gits-Muselli, M.; Menotti, J.; Denis, B.; Bergeron, A.; Legrand, M.; Lortholary, O.; et al. Molecular identification of Mucorales in human tissues: Contribution of PCR electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 594.e1–594.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengerova, M.; Racil, Z.; Hrncirova, K.; Kocmanova, I.; Volfova, P.; Ricna, D.; Bejdak, P.; Moulis, M.; Pavlovsky, Z.; Weinbergerova, B.; et al. Rapid detection and identification of mucormycetes in bronchoalveolar lavage samples from immunocompromised patients with pulmonary infiltrates by use of high-resolution melt analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 2824–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Chen, X.; Zhu, G.; Yi, H.; Chen, S.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, E.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; et al. Utility of plasma cell-free DNA next-generation sequencing for diagnosis of infectious diseases in patients with hematological disorders. J. Infect. 2023, 86, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaoutis, T.E.; Roilides, E.; Chiou, C.C.; Buchanan, W.L.; Knudsen, T.A.; Sarkisova, T.A.; Schaufele, R.L.; Sein, M.; Sein, T.; Prasad, P.A.; et al. Zygomycosis in children: A systematic review and analysis of reported cases. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2007, 26, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roilides, E.; Zaoutis, T.E.; Walsh, T.J. Invasive zygomycosis in neonates and children. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elitzur, S.; Arad-Cohen, N.; Barg, A.; Litichever, N.; Bielorai, B.; Elhasid, R.; Fischer, S.; Fruchtman, Y.; Gilad, G.; Kapelushnik, J.; et al. Mucormycosis in children with haematological malignancies is a salvageable disease: A report from the Israeli Study Group of Childhood Leukemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2019, 189, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claustre, J.; Larcher, R.; Jouve, T.; Truche, A.S.; Nseir, S.; Cadiet, J.; Zerbib, Y.; Lautrette, A.; Constantin, J.M.; Charles, P.E.; et al. Mucormycosis in intensive care unit: Surgery is a major prognostic factor in patients with hematological malignancy. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vironneau, P.; Kania, R.; Morizot, G.; Elie, C.; Garcia-Hermoso, D.; Herman, P.; Lortholary, O.; Lanternier, F.; French Mycosis Study, G. Local control of rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis dramatically impacts survival. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, O336–O339. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pahnev, Y.; Avramova, B.; Gabrovska, N.; Dontcheva, Y.; Tacheva, G.; Minkin, K.; Kreipe, H.; Yurukova, N.; Penkov, M.; Kartulev, N.; et al. A Rare Case of Rhizomucor pusillus Infection in a 3-Year-Old Child with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Presenting with Lung and Brain Abscesses—Case Report. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2026, 18, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr18010002

Pahnev Y, Avramova B, Gabrovska N, Dontcheva Y, Tacheva G, Minkin K, Kreipe H, Yurukova N, Penkov M, Kartulev N, et al. A Rare Case of Rhizomucor pusillus Infection in a 3-Year-Old Child with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Presenting with Lung and Brain Abscesses—Case Report. Infectious Disease Reports. 2026; 18(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr18010002

Chicago/Turabian StylePahnev, Yanko, Boryana Avramova, Natalia Gabrovska, Yolin Dontcheva, Genoveva Tacheva, Krasimir Minkin, Hans Kreipe, Nadezhda Yurukova, Marin Penkov, Nikola Kartulev, and et al. 2026. "A Rare Case of Rhizomucor pusillus Infection in a 3-Year-Old Child with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Presenting with Lung and Brain Abscesses—Case Report" Infectious Disease Reports 18, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr18010002

APA StylePahnev, Y., Avramova, B., Gabrovska, N., Dontcheva, Y., Tacheva, G., Minkin, K., Kreipe, H., Yurukova, N., Penkov, M., Kartulev, N., Antonova, Z., Oparanova, V., Tolekova, N., Moutaftchieva, P., Mladenov, B., Hristova, P., Gabrovski, K., Velizarova, S., Spasova, A., & Shivachev, H. (2026). A Rare Case of Rhizomucor pusillus Infection in a 3-Year-Old Child with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Presenting with Lung and Brain Abscesses—Case Report. Infectious Disease Reports, 18(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr18010002