Atypical Blistering Manifestation of Secondary Syphilis: Case Report and Review of Reported Cases

Abstract

1. Introduction

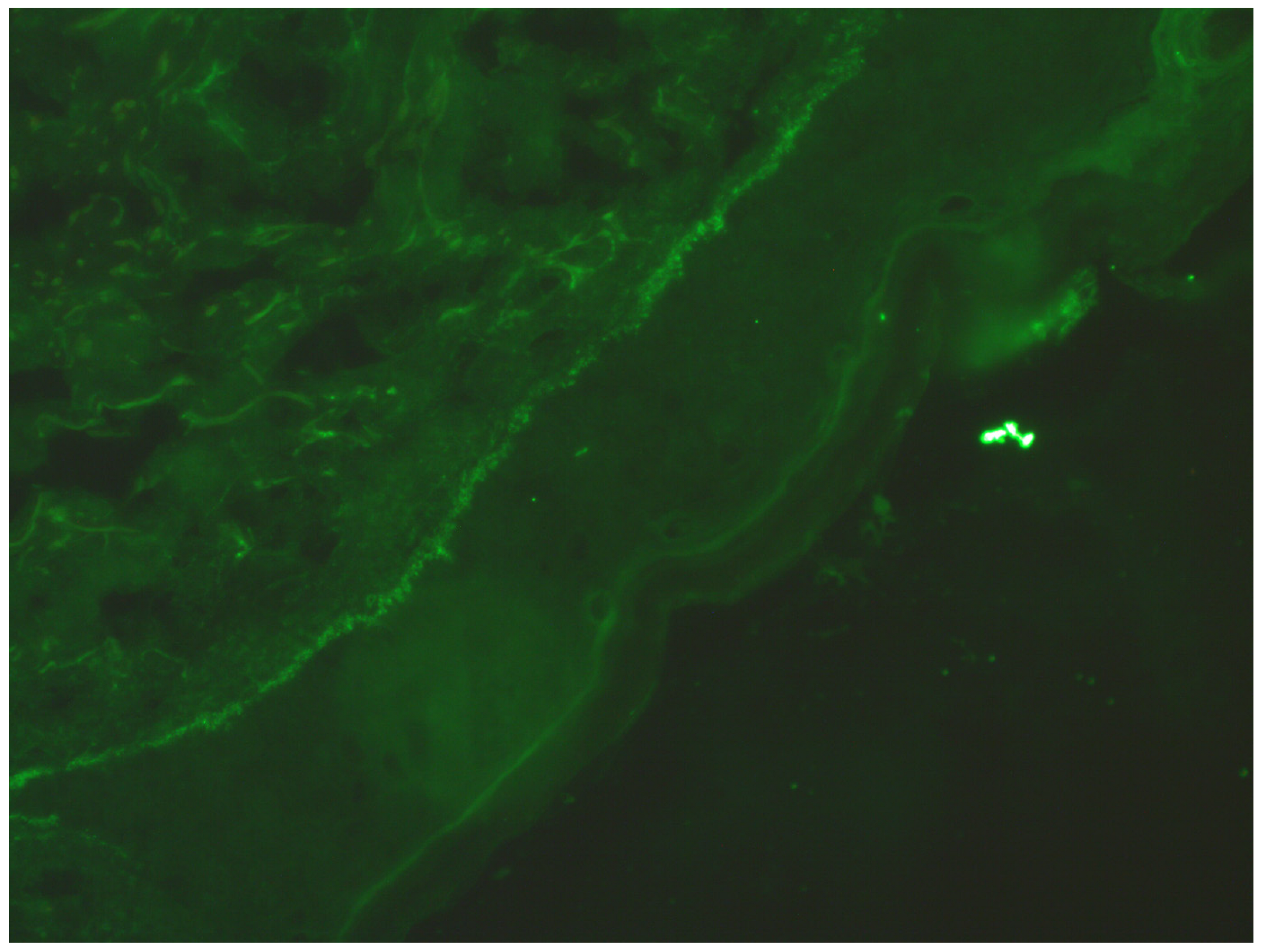

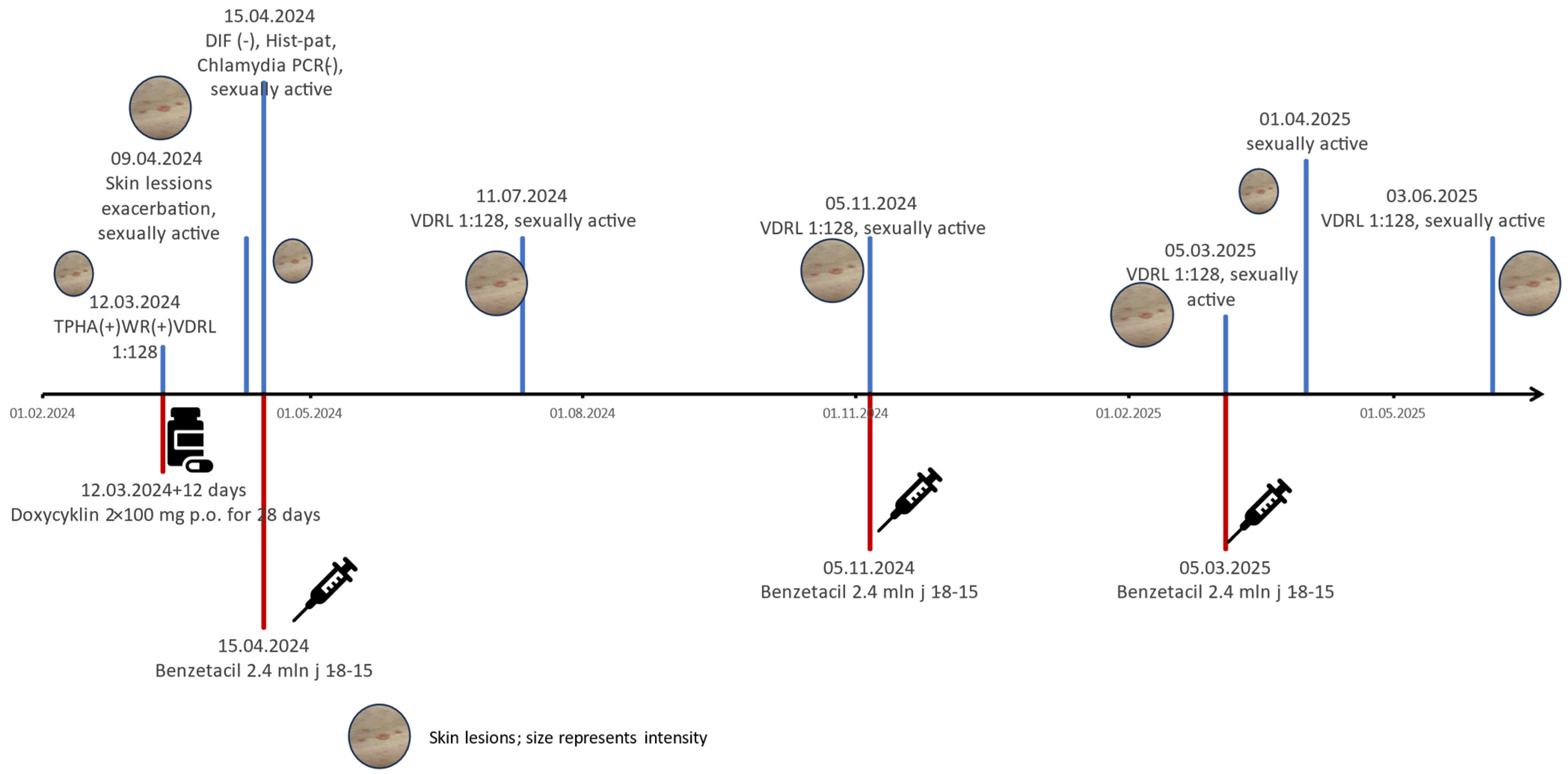

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janier, M.; Unemo, M.; Dupin, N.; Tiplica, G.S.; Potočnik, M.; Patel, R. 2020 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Available online: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Treponema pallidum (Syphilis). 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-guidelines-for-the-treatment-of-treponema-pallidum-(syphilis) (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Miedziński, F. Choroby Skóry i Weneryczne; Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich: Warszawa, Poland, 1985; pp. 15–301. [Google Scholar]

- Jabłońska, S. Choroby Weneryczne; Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich: Warszawa, Poland, 1967; pp. 344–401. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, F. Choroby Weneryczne; Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich: Warszawa, Poland, 1950; pp. 35–281. [Google Scholar]

- Hira, S.K.; Patel, J.S.; Bhat, S.G.; Chilikima, K.; Mooney, N. Clinical manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int. J. Dermatol. 1987, 26, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balagula, Y.; Mattei, P.L.; Wisco, O.J.; Erdag, G.; Chien, A.L. The great imitator revisited: The spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2014, 53, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noppakun, N.; Dinehart, S.M.; Solomon, A.R. Pustular secondary syphilis. Int. J. Dermatol. 1987, 26, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, W.; Li, F.; Chen, S.; Tian, H. Isolated initial clavus-like rash: A rare presentation of secondary syphilis. Int. J. STD AIDS 2025, 36, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourmishev, L.A.; Dourmishev, A.L. Syphilis: Uncommon presentations in adults. Clin. Dermatol. 2005, 23, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, C.E.; Onyekaba, N.A.; Lucas, M.; Jukic, D. Cutaneous Secondary Syphilis Resembling Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer. Cureus 2020, 12, e10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, J.K.; Choi, S.R.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, D.H.; Yoon, M.S.; Jo, H.S. Congenital syphilis presenting with a generalized bullous and pustular eruption in a premature newborn. Ann. Dermatol. 2011, 23 (Suppl. S1), S127–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stone, C.J.; Nicholson, L.; Florell, S.R.; Khalighi, M.A.; Lewis, B.K.H. A case of secondary syphilis presenting like pemphigus with positive direct immunofluorescence. JAAD Case Rep. 2023, 42, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mignogna, M.D.; Fortuna, G.; Leuci, S.; Mignogna, C.; Delfino, M. Secondary syphilis mimicking pemphigus vulgaris. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 479–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, P.; Saxe, N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1992, 17, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopelman, H.; Lin, A.; Jorizzo, J.L. A pemphigus-like presentation of secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2019, 5, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, C.C.; Sinha, S.; Sloan, B.; Whitaker-Worth, D.; Murphy, M.J. Comments on Stone et al, “A case of secondary syphilis presenting like pemphigus with positive direct immunofluorescence”. JAAD Case Rep. 2024, 52, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arora, S.; Dhali, T.K.; Haroon, M.A. Vesicular syphilid in a seropositive patient. Int. J. STD AIDS 2013, 24, 905–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourari, S.; Bulai-Livideanu, C.; Giordano-Labadie, F.; Lamant, L.; Launay, F.; Viraben, R.; Paul, C. Syphilis secondaire bulleuse [Bullous secondary syphilis]. Presse Med. 2011, 40, 550–553. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnirring-Judge Molly, A.; Gustaferro, C.; Terol, C. Vesicobullous syphilis: A case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2011, 50, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age | Sex | Direct Immunofluorescence | Histopathology | Antibodies Anti-Desmoglein 1 or 3 | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone et al. [14] | 60 | male | granular IgG on the surface of epithelial cell continuous in multiple areas but seldom covered the entire epithelial cell surface | parakeratosis with inflammatory cell debris overlying an epidermis manifesting focal intraepithelial acantholysis involving follicle, superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial nodular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes with large numbers of plasma cells and a few scattered eosinophils, histiocytes and neutrophils | not done | penicillin G 24 mln U/day iv 14 days—complete resolution of skin lesions |

| Mignogna et al. [15] | 47 | female | positive for intercellular cement substance (ICS), with its classic ‘net-like’ aspect | suprabasal epithelial detachment with a prominent eosino-neutrophilic infiltrate, suggesting a possible PV | negative | benzathine penicillin G twice a week 1.2 mln U im with skin lesions resolution in 4 weeks |

| Lawrence et al. [16] | 40 | male | linear IgG and C3 at the basement membrane | blister with uni-locular subepidermal vesicle with perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and occasional eosinophils and plasma cells in upper-dermis | negative | procaine penicillin for 10 days with skin lesions resolution |

| Kopelman et al. [17] | 18 | male | negative | subcorneal acantholytic vesicle containing neutrophils. The underlying superficial dermis contains a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and occasional eosinophils | negative | benzathine penicillin G of one dose with skin lesions resolution |

| Pacheco [18] | 52 | female | no data | lichenoid and perivascular dermatitis with numerous plasma cells, negative immunostaining for spirochetes | positive IgG desmoglein-1 and borderline/indeterminate desmoglein-3 antibody levels | benzathine penicillin G im 1-8-15 with skin lesion resolution with hyperpigmentation |

| Arora et al. [19] | 45 | male | not done | lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and plasma cells | Not done | benzathine penicillin G 2.4 mln im 1-8-15 with skin lesions resolution |

| Lourari et al. [20] | 45 | male | not done | focally ulcerated epidermis, beneath which developed an inflammatory lesion rich in mature plasma cells, extending through the entire thickness of the dermis down to the hypodermis | Not done | benzathine penicillin 2.4 mln U im 1-8-15 with skin lesions resolution |

| Schnirring-Judge et al. [21] | 41 | male | not done | not done | Not done | benzathine penicillin G 2.4 mln U im once with skin lesions resolution |

| Described patient | 46 | male | negative | subcorneal and subepidermal blisters with inflammatory infiltration consisting of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils, localised in and under the epidermis and around skin appendages. No plasmocytes we observed. | negative | benzathine penicillin G 2.4 mln U im 1-8-15 but because of no decrease in VDRL titers (reinfection?) the cycle was repeated 3 times |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markiewicz, A.; Skórka, A.; Owczarczyk-Saczonek, A. Atypical Blistering Manifestation of Secondary Syphilis: Case Report and Review of Reported Cases. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060143

Markiewicz A, Skórka A, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A. Atypical Blistering Manifestation of Secondary Syphilis: Case Report and Review of Reported Cases. Infectious Disease Reports. 2025; 17(6):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060143

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkiewicz, Agnieszka, Aleksandra Skórka, and Agnieszka Owczarczyk-Saczonek. 2025. "Atypical Blistering Manifestation of Secondary Syphilis: Case Report and Review of Reported Cases" Infectious Disease Reports 17, no. 6: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060143

APA StyleMarkiewicz, A., Skórka, A., & Owczarczyk-Saczonek, A. (2025). Atypical Blistering Manifestation of Secondary Syphilis: Case Report and Review of Reported Cases. Infectious Disease Reports, 17(6), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060143