A Comparison of the Risk of Viral Load Blips in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Patients on Two-Drug Versus Three-Drug Antiretroviral Regimens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Eligibility

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Definitions and Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

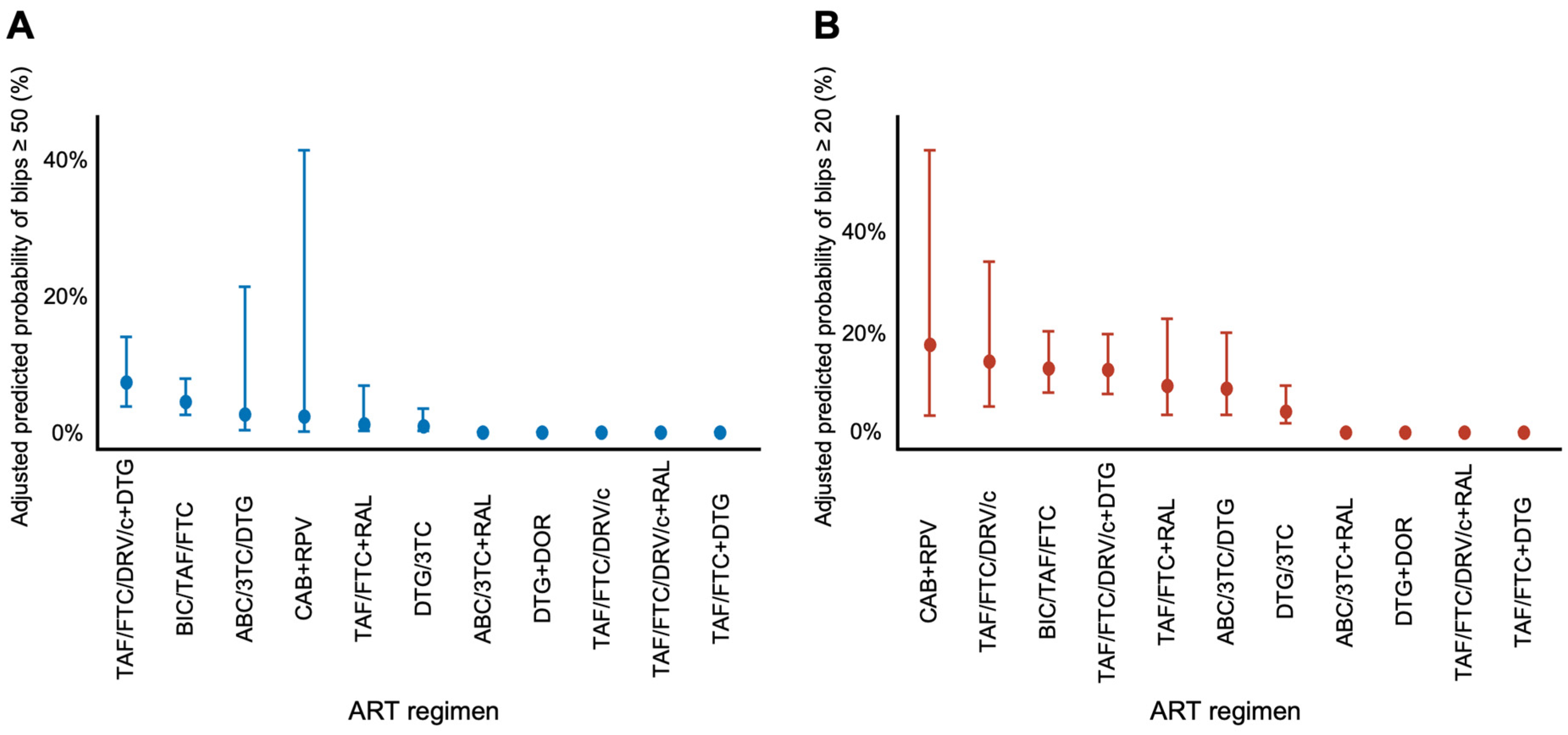

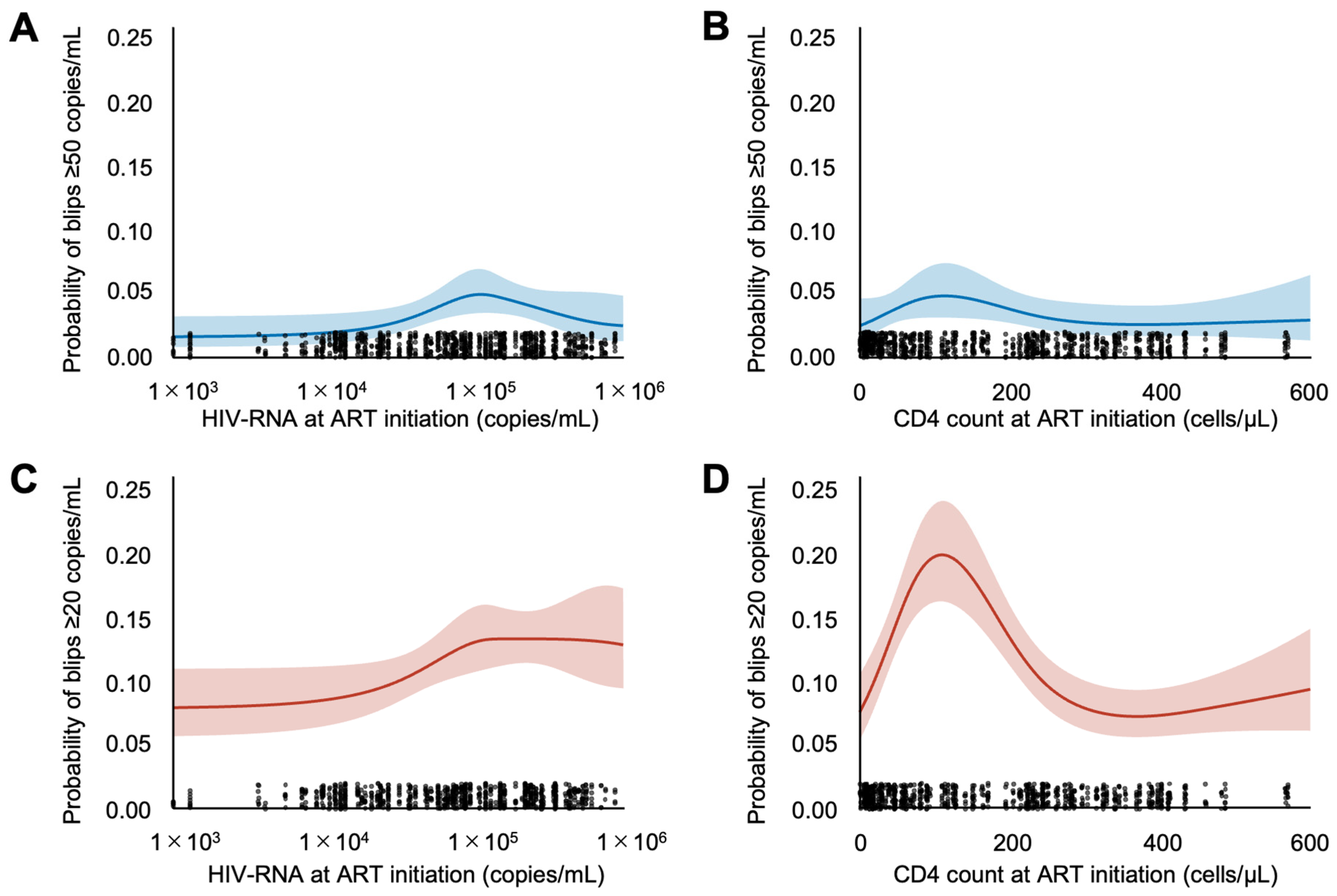

3.2. Viral Blip Occurrence

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: A collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 2017, 4, E349–E356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, B.S.; Lédo, A.P.; Lins-Kusterer, L.; Luz, E.; Prieto, I.R.; Brites, C. Changes health-related quality of life in HIV-infected patients following initiation of antiretroviral therapy: A longitudinal study. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 23, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, A.; Seet, J.; Phillips, E.J. The evolution of three decades of antiretroviral therapy: Challenges, triumphs and the promise of the future: Three decades of antiretroviral therapy. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockstroh, J.K.; DeJesus, E.; Henry, K.; Molina, J.-M.; Gathe, J.; Ramanathan, S.; Wei, X.; Plummer, A.; Abram, M.; Cheng, A.K.; et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF vs ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus coformulated emtricitabine and tenofovir DF for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: Analysis of week 96 results: Analysis of week 96 results. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2013, 62, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walmsley, S.L.; Antela, A.A.; Clumeck, N.; Duiculescu, D.; Eberhard, A.A.; Gutiérrez, F.; Hocqueloux, L.L.; Maggiolo, F.F.; Sandkovsky, U.U.; Granier, C.C.; et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1807–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sax, P.E.; Arribas, J.R.; Orkin, C.; Lazzarin, A.; Pozniak, A.; DeJesus, E.; Maggiolo, F.; Stellbrink, H.-J.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Acosta, R.; et al. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide as initial treatment for HIV-1: Five-year follow-up from two randomized trials. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Richmond, G.J.; Newman, C.; Osiyemi, O.; Cade, J.; Brinson, C.; De Vente, J.; Margolis, D.A.; Sutton, K.C.; Wilches, V.; et al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine for HIV-1 suppression: Switch to 2-monthly dosing after 5 years of daily oral therapy. AIDS 2022, 36, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettles, R.E.; Kieffer, T.L.; Kwon, P.; Monie, D.; Han, Y.; Parsons, T.; Cofrancesco, J.; Gallant, J.E.; Quinn, T.C.; Jackson, B.; et al. Intermittent HIV-1 viremia (Blips) and drug resistance in patients receiving HAART. JAMA 2005, 293, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.; Rickenbach, M.; Calmy, A.; Bernasconi, E.; Staehelin, C.; Schmid, P.; Cavassini, M.; Battegay, M.; Günthard, H.F.; Bucher, H.C.; et al. Transient detectable viremia and the risk of viral rebound in patients from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvstam, O.; Malmborn, K.; Elén, S.; Marrone, G.; García, F.; Zazzi, M.; Sönnerborg, A.; Böhm, M.; Seguin-Devaux, C.; Björkman, P. Virologic failure following low-level viremia and viral blips during antiretroviral therapy: Results from a European multicenter cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Levert, A.; Yeung, J.; Starr, M.; Cameron, J.; Williams, R.; Rismanto, N.; Stark, T.; Druery, D.; Prasad, S.; et al. HIV-1 viral blips are associated with repeated and increasingly high levels of cell-associated HIV-1 RNA transcriptional activity. AIDS 2021, 35, 2095–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siliciano, J.D.; Kajdas, J.; Finzi, D.; Quinn, T.C.; Chadwick, K.; Margolick, J.B.; Kovacs, C.; Gange, S.; Siliciano, R.F. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, P.; Madero, J.S.; Arribas, J.R.; Antinori, A.; Ortiz, R.; Clarke, A.E.; Hung, C.-C.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Girard, P.-M.; Sievers, J.; et al. Dolutegravir plus lamivudine versus dolutegravir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2): Week 48 results from two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trials. Lancet 2019, 393, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, P.; Madero, J.S.; Arribas, J.R.; Antinori, A.; Ortiz, R.; Clarke, A.E.; Hung, C.-C.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Girard, P.-M.; Sievers, J.; et al. Three-year durable efficacy of dolutegravir plus lamivudine in antiretroviral therapy—Naive adults with HIV-1 infection. AIDS 2022, 36, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Underwood, M.; Llibre, J.M.; Morell, E.B.; Brinson, C.; Moreno, J.S.; Scholten, S.; Moore, R.; Saggu, P.; Oyee, J.; et al. Very-low-level viremia, inflammatory biomarkers, and associated baseline variables: Three-year results of the randomized TANGO study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofad626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, M.; Urbaityte, R.; Wang, R.; Horton, J.; Oyee, J.; Wynne, B.; Fox, D.; Jones, B.; Man, C.; Sievers, J. Dolutegravir + lamivudine vs. Dolutegravir + tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine: Very-low-level HIV-1 replication through 144 weeks in the GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 studies. Viruses 2024, 16, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/adult-adolescent-arv/guidelines-adult-adolescent-arv.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Sterling, T.R.; Njie, G.; Zenner, D.; Cohn, D.L.; Reves, R.; Ahmed, A.; Menzies, D.; Horsburgh, C.R.; Crane, C.M.; Burgos, M.; et al. Guidelines for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2020. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2020, 69, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, R.T.; Bedimo, R.; Hoy, J.F.; Landovitz, R.J.; Smith, D.M.; Eaton, E.F.; Lehmann, C.; Springer, S.A.; Sax, P.E.; Thompson, M.A.; et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2022 recommendations of the international antiviral society-USA panel: 2022 recommendations of the international antiviral society-USA panel. JAMA 2023, 329, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 1992, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.M.; Krentz, H.; Gill, M.J.; Hogan, D.B. Managing HIV infection in patients older than 50 years. CMAJ 2018, 190, E1253–E1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents With HIV. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/archive/adult-adolescent-oi-2024-10-08.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Crowell, T.A.; Hsieh, H.-C.; Wang, X.; Chu, X.; Gayle, B.; Berjohn, C.M.; Blaylock, J.M.; Yabes, J.M.; Larson, D.T.; Powers, J.H.; et al. Antiretroviral therapy within two years of HIV acquisition is associated with fewer viral blips: A retrospective analysis of over 20 years of data from the U.S. military HIV Natural History Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 81, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraysse, J.; Priest, J.; Turner, M.; Hill, S.; Jones, B.; Verdier, G.; Letang, E. Real-world effectiveness and tolerability of dolutegravir and lamivudine 2-drug regimen in people living with HIV: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2025, 14, 357–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörstedt, E.; Nilsson, S.; Blaxhult, A.; Gisslén, M.; Flamholc, L.; Sönnerborg, A.; Yilmaz, A. Viral blips during suppressive antiretroviral treatment are associated with high baseline HIV-1 RNA levels. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomen, P.G.A.; Dijkstra, S.; Hofstra, L.M.; Nijhuis, M.M.; Verbon, A.; Mudrikova, T.; Wensing, A.M.J.; Hoepelman, A.I.M.; Van Welzen, B.J. Integrated analysis of viral blips, residual viremia, and associated factors in people with HIV: Results from a retrospective cohort study. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manalel, J.A.; Kaufman, J.E.; Wu, Y.; Fusaris, E.; Correa, A.; Ernst, J.; Brennan-Ing, M. Association of ART regimen and adherence to viral suppression: An observational study of a clinical population of people with HIV. AIDS Res. Ther. 2024, 21, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hocqueloux, L.; Lefeuvre, S.; Bois, J.; Brucato, S.; Alix, A.; Valentin, C.; Peyro-Saint-Paul, L.; Got, L.; Fournel, F.; Dargere, S.; et al. Bioavailability of dissolved and crushed single tablets of bictegravir, emtricitabine, tenofovir alafenamide in healthy adults: The SOLUBIC randomized crossover study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 78, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, N.; Piao, Y.; Rubino, A.; Lee, K.; Chen, M.; Harada, K.; Tanikawa, T.; Naito, T. Relationship between adherence to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide fumarate and clinical outcomes in people with HIV in Japan: A claims database analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | All Patients (n = 121) | Two-Drug Regimen (n = 44) | Three-Drug Regimen (n = 77) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y [range] | 37 [22–73] | 39.5 [24–73] | 37 [22–65] | 0.042 |

| Male—n (%) | 115 (95.0) | 39 (88.6) | 76 (98.7) | 0.024 |

| Baseline HIV-RNA levels, copies/mL [range] | 87,500 [320–7,100,000] | 75,000 [320–750,000] | 88,000 [1000–7,100,000] | 0.105 |

| Baseline CD4 cell count, cells/μL [range] | 162 [0–871] | 196.5 [1–566] | 152 [0–871] | 0.731 |

| AIDS diagnosis—n (%) | 53 (43.8) | 17 (38.6) | 36 (46.8) | 0.448 |

| Duration of ART, y [range] | 7.7 [0.9–17.0] | 5.0 [0.9–14.3] | 8.2 [3.9–17.0] | <0.001 |

| ART Regimen | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Two-drug regimen | 44 (36.4) |

| DTG/3TC | 35 (28.9) |

| CAB/RPV | 5 (4.1) |

| DTG/DOR | 3 (2.5) |

| DTG/RPV | 1 (0.8) |

| Three-drug regimen | 77 (63.6) |

| BIC/TAF/FTC | 70 (57.9) |

| TAF/FTC + RAL | 3 (2.5) |

| ABC/3TC/DTG | 1 (0.8) |

| TAF/FTC/DRV/c + RAL | 1 (0.8) |

| TAF/FTC/DRV/c + DTG | 1 (0.8) |

| ABC/3TC + RAL | 1 (0.8) |

| ART Regimen | Total Tests | Blips ≥ 50, n (%) | Blips ≥ 20, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-drug regimen | 546 | 7 (1.3) | 29 (5.3) |

| DTG/3TC | 455 | 5 (1.1) | 18 (4.0) |

| CAB/RPV | 62 | 2 (3.2) | 11 (17.7) |

| DTG/DOR | 16 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| DTG/RPV | 13 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Three-drug regimen | 1620 | 63 (3.9) | 214 (13.2) |

| BIC/TAF/FTC | 1272 | 57 (4.5) | 179 (14.1) |

| TAF/FTC + RAL | 114 | 2 (1.8) | 14 (12.3) |

| ABC/3TC/DTG | 80 | 3 (3.8) | 11 (13.8) |

| TAF/FTC/DRV/c | 79 | 0 (0.0) | 7 (8.9) |

| DRV/c + DTG | 23 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) |

| TAF/FTC/DRV/c + RAL | 18 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| TAF/FTC/DRV/c + DTG | 16 | 1 (6.2) | 2 (12.5) |

| ABC/3TC + RAL | 14 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| TAF/FTC + DTG | 4 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Factor | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Blips ≥ 50 copies/mL | ||

| Three-drug regimen | 2.64 (0.91–7.70) | 0.075 |

| Age | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.278 |

| AIDS diagnosis | 0.78 (0.25–2.49) | 0.679 |

| HIV-RNA at ART initiation | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.455 |

| CD4 cell count at ART initiation | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.476 |

| Duration of ART (y) | 0.92 (0.81–1.04) | 0.162 |

| Blips ≥ 20 copies/mL | ||

| Three-drug regimen | 1.76 (0.76–4.08) | 0.190 |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.317 |

| AIDS diagnosis | 0.78 (0.30–2.02) | 0.613 |

| HIV-RNA at ART initiation | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.881 |

| CD4 cell count at ART initiation | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.246 |

| Duration of ART (y) | 0.87 (0.79–0.95) | 0.003 |

| Subgroup | N | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | P for Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blips ≥ 50 copies/mL | ||||

| AIDS diagnosis | 0.987 | |||

| Yes | 50 | 2.80 (0.70–11.24) | 0.148 | |

| No | 64 | 2.86 (0.59–13.82) | 0.191 | |

| Age (y) | 0.642 | |||

| <50 | 79 | 2.17 (0.24–19.53) | 0.489 | |

| ≥50 | 58 | 3.47 (1.29–9.29) | 0.013 | |

| HIV-RNA at ART initiation | NA | |||

| <500,000 | 100 | 2.44 (0.81–7.37) | 0.113 | |

| ≥500,000 | 14 | NA | NA | |

| CD4 cell count at ART initiation | 0.592 | |||

| <200 | 62 | 4.01 (1.34–12.00) | 0.013 | |

| ≥200 | 52 | 1.92 (0.21–17.22) | 0.559 | |

| Duration of ART | NA | |||

| <2 y | 16 | NA | NA | |

| ≥2 y | 114 | NA | NA | |

| Blips ≥ 20 copies/mL | ||||

| AIDS diagnosis | 0.5 | |||

| Yes | 50 | 2.84 (0.91–8.83) | 0.071 | |

| No | 64 | 1.58 (0.52–4.84) | 0.423 | |

| Age (y) | 0.171 | |||

| <50 | 79 | 1.20 (0.36–4.04) | 0.763 | |

| ≥50 | 58 | 3.27 (1.53–6.99) | 0.002 | |

| HIV-RNA at ART initiation | 0.526 | |||

| <500,000 | 100 | 1.75 (0.75–4.04) | 0.193 | |

| ≥500,000 | 14 | 5.36 (0.06–502) | 0.468 | |

| CD4 cell count at ART initiation | 0.954 | |||

| <200 | 62 | 2.53 (1.30–4.91) | 0.006 | |

| ≥200 | 52 | 1.38 (0.24–7.93) | 0.716 | |

| Duration of ART | 0.362 | |||

| <2 y | 16 | 1.11 (0.40–3.06) | 0.846 | |

| ≥2 | 114 | 2.06 (0.82–5.20) | 0.126 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamaguchi, K.; Ishihara, M.; Ikoma, Y.; Sugiyama, H.; Watanabe, D.; Fujita, K.; Lee, S.; Morishita, T.; Kanemura, N.; Shimizu, M.; et al. A Comparison of the Risk of Viral Load Blips in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Patients on Two-Drug Versus Three-Drug Antiretroviral Regimens. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060141

Yamaguchi K, Ishihara M, Ikoma Y, Sugiyama H, Watanabe D, Fujita K, Lee S, Morishita T, Kanemura N, Shimizu M, et al. A Comparison of the Risk of Viral Load Blips in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Patients on Two-Drug Versus Three-Drug Antiretroviral Regimens. Infectious Disease Reports. 2025; 17(6):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060141

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamaguchi, Kimihiro, Masashi Ishihara, Yoshikazu Ikoma, Hitomi Sugiyama, Daichi Watanabe, Kei Fujita, Shin Lee, Tetsuji Morishita, Nobuhiro Kanemura, Masahito Shimizu, and et al. 2025. "A Comparison of the Risk of Viral Load Blips in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Patients on Two-Drug Versus Three-Drug Antiretroviral Regimens" Infectious Disease Reports 17, no. 6: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060141

APA StyleYamaguchi, K., Ishihara, M., Ikoma, Y., Sugiyama, H., Watanabe, D., Fujita, K., Lee, S., Morishita, T., Kanemura, N., Shimizu, M., & Tsurumi, H. (2025). A Comparison of the Risk of Viral Load Blips in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Patients on Two-Drug Versus Three-Drug Antiretroviral Regimens. Infectious Disease Reports, 17(6), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060141