Multidisciplinary Approach in Rare, Fulminant-Progressing, and Life-Threatening Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

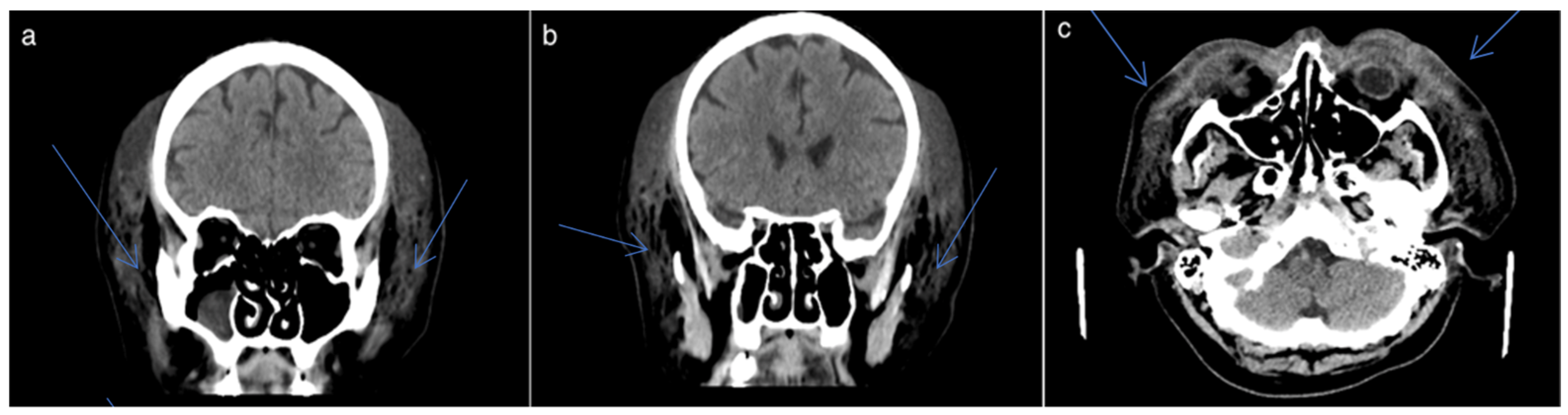

2.1. Clinical Presentation

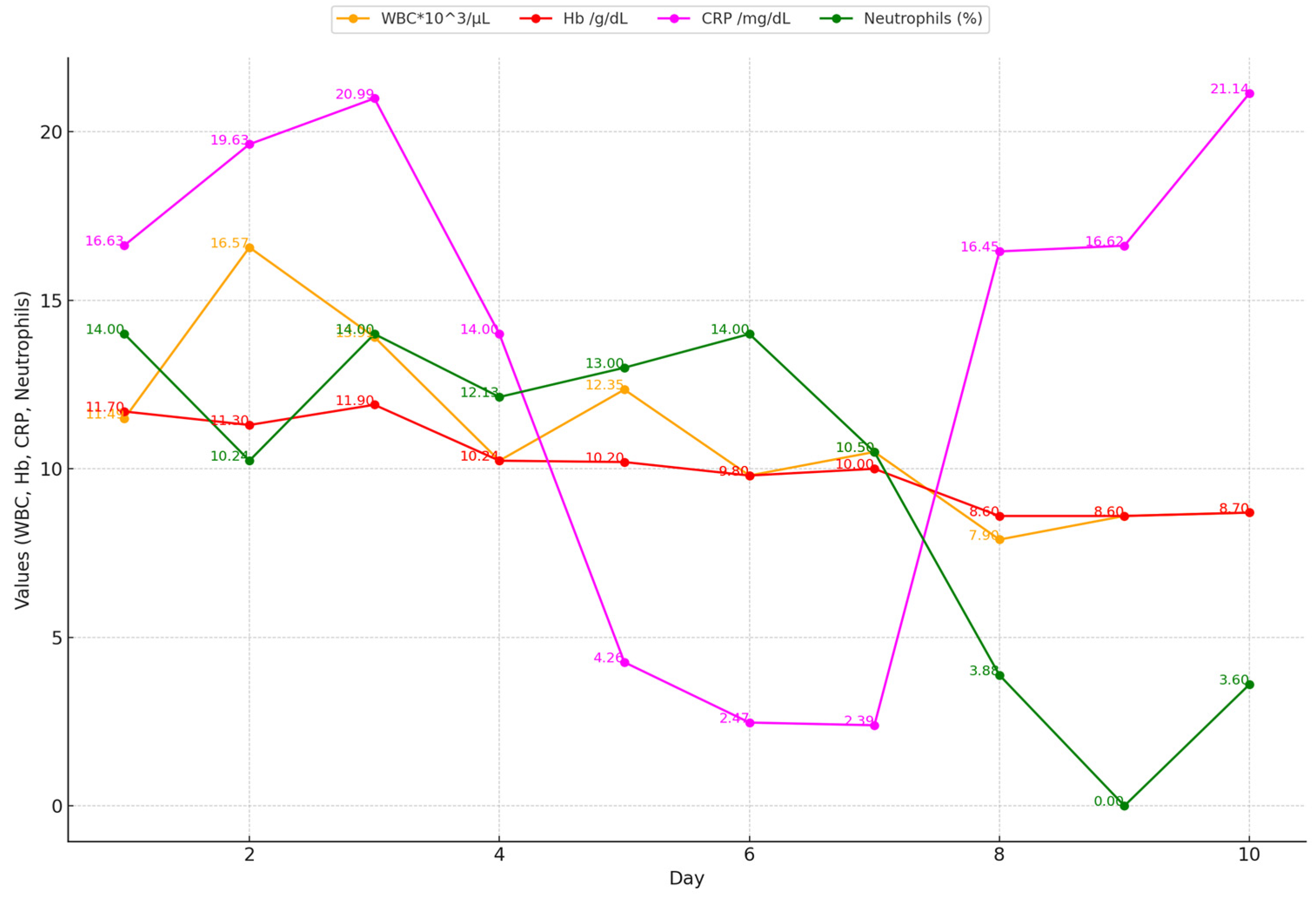

2.2. Biological Markers

2.3. Microbiological Findings

2.4. Surgical Interventions

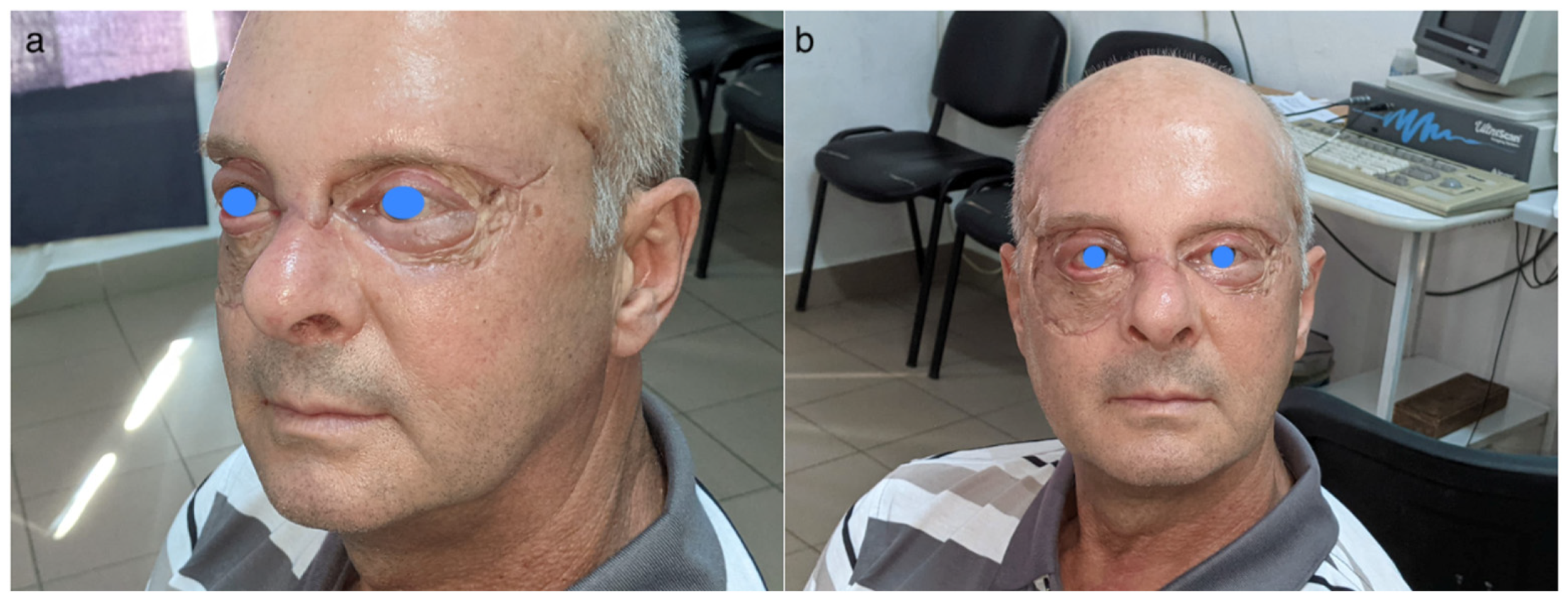

2.5. Outcome

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, L.E.; Shaye, D.A. Noma and Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Face and Neck. Facial Plast. Surg. 2021, 37, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.H.; Khin, L.W.; Heng, K.S.; Tan, K.C.; Low, C.O. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: A tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribb, B.I.; Wang, M.T.M.; Kulasegaran, S.; Gamble, G.D.; MacCormick, A.D. The SIARI Score: A Novel Decision Support Tool Outperforms LRINEC Score in Necrotizing Fasciitis. World J. Surg. 2019, 43, 2393–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breidung, D.; Grieb, G.; Malsagova, A.T.; Barth, A.A.; Billner, M.; Hitzl, W.; Reichert, B.; Megas, I.F. Time Is Fascia: Laboratory and Anamnestic Risk Indicators for Necrotizing Fasciitis. Surg. Infect. 2022, 23, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megas, I.F.; Delavari, S.; Edo, A.M.; Habild, G.; Billner, M.; Reichert, B.; Breidung, D. Prognostic Factors in Necrotizing Fasciitis: Insights from a Two-Decade, Two-Center Study Involving 209 Cases. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2024, 16, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzada, S.; Rao, A.; Ghazavi, H. Necrotizing fasciitis of the face: Current concepts in cause, diagnosis and management. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 30, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.H.; Wang, Y.S. The diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 18, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, F.; de Gier, B.; Brandwagt, D.A.H.; Groenwold, R.H.H.; Keizer, J.; Hietbrink, F. Incidence and mortality of necrotizing fasciitis in The Netherlands: The impact of group A Streptococcus. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taviloglu, K.; Yanar, H. Necrotizing fasciitis: Strategies for diagnosis and management. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2007, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.V.; Thomas, S.; Nair, P.P.; Cyriac, S.; Tripathi, G.M. Necrotizing fasciitis of face--our experience in its management. BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 2011, bcr0720114453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina, T.; Razazi, K.; Ourghanlian, C.; Woerther, P.L.; Chosidow, O.; Lepeule, R.; de Prost, N. Antibiotics in Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Y.; Huang, T.Y.; Chen, J.L.; Kuo, L.T.; Huang, K.C.; Tsai, Y.H. Rational Use of Ceftriaxone in Necrotizing Fasciitis and Mortality Associated with Bloodstream Infection and Hemorrhagic Bullous Lesions. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferzli, G.; Sukato, D.C.; Mourad, M.; Kadakia, S.; Gordin, E.A.; Ducic, Y. Aggressive Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Head and Neck Resulting in Massive Defects. Ear Nose Throat J. 2019, 98, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Fotea, M.C.; Luca, S.; Moraru, D.C.; Filip, A.; Olinici-Temelie, D.; Lunca, S.; Carp, A.C.; Grosu, O.M.; Amarandei, A.; et al. Periorbital Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis in Adults: A Rare Severe Disease with Complex Diagnosis and Surgical Treatment-A New Case Report and Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lai, C.C. Concurrent Pseudomonas Periorbital Necrotizing Fasciitis and Endophthalmitis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Pathogens 2021, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueppers, P.; Bozalka, R.; Kopp, R.; Menges, A.L.; Reutersberg, B.; Schrimpf, C.; Moreno Rivero, F.J.; Zimmermann, A. The Use of Intact Fish Skin Grafts in the Treatment of Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Leg: Early Clinical Experience and Literature Review on Indications for Intact Fish Skin Grafts. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qurayshi, Z.; Nichols, R.L.; Killackey, M.T.; Kandil, E. Mortality Risk in Necrotizing Fasciitis: National Prevalence, Trend, and Burden. Surg. Infect. 2020, 21, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunaratne, D.A.; Tseros, E.A.; Hasan, Z.; Kudpaje, A.S.; Suruliraj, A.; Smith, M.C.; Riffat, F.; Palme, C.E. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis: Systematic review and analysis of 1235 reported cases from the literature. Head Neck 2018, 40, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Cui, G.; Liu, Y.; Guo, J.; Yue, C. O-POSSUM and P-POSSUM as predictors of morbidity and mortality in older patients after hip fracture surgery: A meta-analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2023, 143, 6837–6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabbasy, M.M.; Elsisy, A.A.E.; Mahmoud, A.; Alhanafy, S.S. Comparison between P-POSSUM and NELA risk score for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy in Egyptian patients. BMC Surg. 2023, 23, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaldgaard, L.; Cristall, N.; Gawaziuk, J.P.; Kohja, Z.; Logsetty, S. Predictors of Mortality in Patients With Necrotizing Fasciitis: A Literature Review and Multivariate Analysis. Plast. Surg. 2023, 31, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, S.M.; Tran, A.; Cheng, W.; Rochwerg, B.; Kyeremanteng, K.; Seely, A.J.E.; Inaba, K.; Perry, J.J. Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection: Diagnostic Accuracy of Physical Examination, Imaging, and LRINEC Score: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, C.; Urbina, T.; Bosc, R.; Parks, T.; Sriskandan, S.; de Prost, N.; Chosidow, O. Necrotising soft-tissue infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, e81–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misiakos, E.P.; Bagias, G.; Papadopoulos, I.; Danias, N.; Patapis, P.; Machairas, N.; Karatzas, T.; Arkadopoulos, N.; Toutouzas, K.; Alexakis, N.; et al. Early Diagnosis and Surgical Treatment for Necrotizing Fasciitis: A Multicenter Study. Front. Surg. 2017, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.P.; Cohn, J.E.; Shokri, T.; Bundrick, P.; Ducic, Y. Surgical Management of Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Head and Neck. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2022, 33, e858–e861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biological Constants at Admission | |

|---|---|

| WBC (1000 cells/µL) | 17.9 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 19.63 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 142 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.55 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 112 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pertea, M.; Luca, S.; Tatar, R.; Huzum, B.; Ciofu, M.; Poroch, V.; Palade, D.O.; Vrinceanu, D.; Balan, M.; Grosu, O.M. Multidisciplinary Approach in Rare, Fulminant-Progressing, and Life-Threatening Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2024, 16, 1045-1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr16060084

Pertea M, Luca S, Tatar R, Huzum B, Ciofu M, Poroch V, Palade DO, Vrinceanu D, Balan M, Grosu OM. Multidisciplinary Approach in Rare, Fulminant-Progressing, and Life-Threatening Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis. Infectious Disease Reports. 2024; 16(6):1045-1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr16060084

Chicago/Turabian StylePertea, Mihaela, Stefana Luca, Raluca Tatar, Bogdan Huzum, Mihai Ciofu, Vladimir Poroch, Dragos Octavian Palade, Daniela Vrinceanu, Mihail Balan, and Oxana Madalina Grosu. 2024. "Multidisciplinary Approach in Rare, Fulminant-Progressing, and Life-Threatening Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis" Infectious Disease Reports 16, no. 6: 1045-1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr16060084

APA StylePertea, M., Luca, S., Tatar, R., Huzum, B., Ciofu, M., Poroch, V., Palade, D. O., Vrinceanu, D., Balan, M., & Grosu, O. M. (2024). Multidisciplinary Approach in Rare, Fulminant-Progressing, and Life-Threatening Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis. Infectious Disease Reports, 16(6), 1045-1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr16060084

_Rachiotis.png)