Abstract

Carcinoid syndrome (CS) is the most common functional syndrome associated with neuroendocrine neoplasia (NEN), particularly in intestinal NEN with extensive liver metastases. Owing to the heterogenous symptomatic scenario present in CS, recognition of these patients may be challenging. In this review, we explore some key clinical factors used to identify patients affected by CS, with particular focus on differential diagnoses of diarrhea, which is the main symptom of CS. Moreover, we highlight the importance of nutritional screening as a clinical indication to prevent malnutrition and to manage the most common nutrient deficiencies present in these patients.

1. Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasia (NEN) is a heterogenous group of tumors arising from the diffuse neuroendocrine system, which is distributed throughout the body and is able to secrete a variety of hormones and bioactive amines [1]. Although considered relatively rare, their incidence and prevalence continue to rise globally, particularly for small intestinal, rectal, and pancreatic NEN [2]. Gastro-entero-pancreatic (GEP) NEN, which represents the most frequent localization, increased more than sixfold from 1997 to 2012, accounting for about 0.5% on new cancer diagnoses [3]. Their prognosis is affected by several factors including the primary tumor site, staging and tumor grade; however, proliferative activity, expressed as the Ki-67 index, is considered the strongest prognostic factor for providing useful information to choose appropriate treatment options [4]. NEN is known to be a heterogenous disease in terms of both its pathological and clinical features; thus, the management of these patients may be challenging for physicians [5]. The clinical scenario varies widely depending on the primary tumor site, staging, histopathological features, and the ability, or lack of tumor cells to secrete hormones or vasoactive substances. NEN is, in fact, clinically divided into functional (30%) and non-functional (70%) tumors according to their ability to secrete hormones or peptides, which cause a wide variety of symptoms related to a clinical syndrome [1]. Carcinoid syndrome (CS) is the most common functional syndrome associated with NEN due to the release of serotonin and vasoactive substances in the systemic circulation [6]. Most frequent manifestations of this syndrome are diarrhea and flushing (occurring in approximately 80% of cases), an asthma-like syndrome (12% of cases), and long-term complications, such as mesenteric fibrosis and carcinoid heart disease (CHD) [6,7].

Recent data from the SEER database in USA reported an estimated CS prevalence of 19% in patients with NEN. These are in accordance with the European data, which showed a prevalence of carcinoid syndrome of 25% in 837 patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic (GEP) NEN and 20% in all 1263 NENs patients [3,8].

More than 40 substances are known to be involved in the pathogenesis of CS, but the main mediator is serotonin (5-HT), which is considered the primary marker associated with the syndrome, and histamine, prostaglandins, and tachykinins. All these substances are usually inactivated in the portal circulation. However, in patients with liver metastases, the production bypasses the metabolism, and CS may occur [9]. 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) is the main metabolite of serotonin and it is the major biomarker used for diagnosis and follow-up. Twenty-four-hour urine collection for 5-HIAA has a sensitivity and specificity of around 90% for small intestine NEN [10].

Early recognition of CS is crucial for patients with NEN in terms of relieving symptoms, improving quality of life, and preventing long-term complications [11].

2. Clinical Presentation

Carcinoid syndrome is characterized by a heterogeneity of symptoms including abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, weight loss, facial flushing, and, in rare cases, skin lesions with hyperkeratosis and pigmentation. Diarrhea and flushing are the most common symptoms, occurring in around 80% of patients [6,7]. Long-term complications of CS, related to pro-fibrotic stimulation, are carcinoid heart disease with different degrees of tricuspid, pulmonary and mitral abnormalities, and mesenteric fibrosis leading to chronic abdominal pain [12,13,14].

In the majority of cases, CS occurs in patients affected by NEN of the small intestine with extensive liver metastases due to the blood bypassing hepatic inactivation when entering the systemic circulation. Liver metastases are present in around 87–100% of patients with CS. In lower numbers (5–13%), CS may present in the absence of liver involvement, particularly in patients with ovarian, testicular, or retroperitoneal metastases, or those with primary lung NEN [14].

Treatment of individual patients should consider the patient’s performance status and the severity of complaints, as well as tumor grade, stage, and primary location [15].

3. When to Suspect Carcinoid Syndrome?

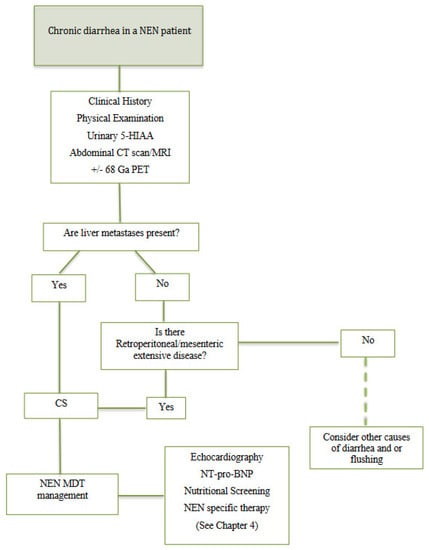

Owing to the heterogenous symptomatic scenario present in CS, recognition of these patients may be challenging. Thus, we identified some key clinical points to be assessed when carcinoid syndrome is suspected (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagnostic work-up in patients with NEN and chronic diarrhea. US: ultrasound; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; 68 Ga PET: 68 Gallium Positron emission tomography; 5-HIAA: 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; CS: carcinoid syndrome; NEN: neuroendocrine neoplasia; MDT: multidisciplinary team; NT-pro-BNP: N-terminal-pro-hormone brain natriuretic peptide; SSA: somatostatin analogues.

3.1. Chronic Diarrhea

Chronic diarrhea is a recurrent symptom in patients with NEN due to different etiologies (Table 1), however, it is also estimated that 4–5% of adults, in the general population, suffer from chronic diarrhea.

The patient’s concept of diarrhea usually refers to stool consistency, but frequency, weight, and volume are also important for a correct definition. Since volume and weight are difficult to quantify in clinical practice, chronic diarrhea is defined by the coexistence of increased frequency (≥3 loose stools/day) and reduced consistency for more than 4 weeks. The clinical assessment used for classifying stool consistency is the Bristol stool scale (BS), which through a graphic stool chart highlights seven fecal categories: diarrhea is considered when BS is above 5 [16]. There are several differential diagnoses of diarrhea to be considered but the most challenging aspect for the physician is to distinguish between organic and functional causes of diarrhea. In general, signs and symptoms suggestive of an organic disease include nocturnal or persistent diarrhea, weight loss, symptoms of diarrhea present for a <3 month duration and biochemical alterations such as leukocytosis, anemia, electrocyte imbalance (hypopotassemia), and nutrient deficiency. Moreover, if alarm features such as an unexplained recent change in bowel habits, blood in the stool, and unintentional weight loss are present, further investigations are required to rule out other potential malignancies [10,16].

Patients with neuroendocrine neoplasia may suffer from chronic diarrhea due to either etiologies strictly related to the tumor itself (surgery complications, side effects of anti-proliferative treatments, hormone over production, etc.) or due to other common gastrointestinal causes that overlap with cancer disease; however, diarrhea in NEN patients is often multifactorial, thus differential diagnoses are challenging [10]. As previously mentioned, a characteristic of these tumors is the possibility to secrete hormones and vasoactive substances in the systemic circulation leading to a diarrhea related to hormone hypersecretion, which occurs in about 30% of patients with NEN (functional tumor) [17]. Among all the possible NEN functional syndromes, CS is the most common, occurring in 30–40% of patients with well-differentiated GI NEN, and is characterized by chronic secretory diarrhea due to hypersecretion of serotonin, which is present in about 80% of patients [6,7]. Notably, patients report watery diarrhea, mild to severe, occurring usually after meals. Moreover, chronic diarrhea in CS patients may lead to dehydration, renal insufficiency, and electrolyte imbalance and malabsorption. In a NEN patient with chronic diarrhea, particularly in cases of intestinal origin and liver metastatic disease, twenty-four-hour urine collection for 5-HIAA must be performed to confirm the diagnosis of CS. Other less common causes of diarrhea due to hormone hypersecretion include Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, Verner–Morrison syndrome, Becker syndrome (Glucagonoma), and syndromes associated with hypersecretion of somatostatin (Somatostatinoma) [10,18].

Table 1.

Potential causes of diarrhea in a patient with NEN6, [10,18,19,20,21,22,23].

Table 1.

Potential causes of diarrhea in a patient with NEN6, [10,18,19,20,21,22,23].

| Diarrhea Due to Hormone Hypersecretion (CS) (30%) | Non-CS-Related Diarrhea (70%) |

|---|---|

| Carcinoid Syndrome (CS) Diarrhea flushing, asthma-like syndrome excess of U-5-HIAA | PEI Steatorrhea weight loss flatulence, FE-1 below 200 mcg/g stool, SSA treatment, GEP surgery, pancreatic primary tumor site, diabetes mellitus |

| Zollinger–Ellison Syndrome Peptic ulcer disease, pyrosis, watery diarrhea responsive to PPI | Short Bowel Syndrome Watery diarrhea, anemia, vitamin deficiencies, resection of terminal ileum and/or right colon or cholecystectomy |

| Verner–Morrison Syndrome Persistent watery diarrhea, electrolyte imbalance, metabolic acidosis, hypokalemia | BAM Watery stool, urgency, fecal incontinence, resection of the terminal ileum and/or right colon or cholecystectomy |

| Becker Syndrome (Glucagonoma) Weight loss, anemia, typical skin lesions, necrolytic migratory erythema, diabetes mellitus diarrhea, cheilitis, glossitis, stomatitis and dyspepsia | Antiproliferative Treatment SSA, target therapies, chemotherapy |

| Somatostatinoma Diabetes mellitus, diarrhea, steatorrhea, and cholelithiasis | Other IBS, coeliac disease, IBD, other malignancies, drug use, thyroid disfunction |

CS: carcinoid Syndrome; U-5-HIAA: urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; PPI: proton pump inhibitor; PEI: pancreatic exocrine insufficiency; FE-1: fecal-elastase 1; SSA: somatostatin analogues; GEP: gastro-entero-pancreatic; BAM: bile acid malabsorption; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

However, most NEN is related to non-functional tumors (about 70%) [17] including several differential diagnoses of diarrhea:

- Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) is one of the most common causes of diarrhea in patients with non- functional NEN [10]. It is caused by reduced secretion or inadequate activity of pancreatic juice and its digestive enzymes, which can manifest as steatorrhea, weight loss, and biochemical changes related to the malabsorption and maldigestion of lipids and fat-soluble micronutrients [19,20]. As a result of the large reserve of the pancreas, PEI usually occurs when >90% of pancreatic secretion is compromised. In NEN patients, PEI may be secondary to the iatrogenic effects of SSA, pancreatic or gastrointestinal surgery, diabetes mellitus, or pancreatic localization of the primary tumor [10,18];

- Short bowel syndrome, when the length of the functional small bowel is less than 200 cm, occurs after extensive small bowel resection disturbs the normal absorptive processes of nutrients and fluids, especially when the ileum, with or without the colon, is involved. The symptoms are often evident in the immediate postoperative period and include watery diarrhea exacerbated by oral intake and, later, weight loss, anemia, and vitamins deficiencies [21,22]. The diagnosis is mainly based on medical history, focusing on surgical procedures involving the small intestine. The degree of absorption is strictly related to the length of the intestine resected, thus it is important to document the extent and location of bowel resection: if only the proximal bowel (jejunum) is removed, malabsorption and malnutrition are less impacted; however, even a loss of 100 cm of ileum causes steatorrhea due to its important role in bile salt and water resorption [21]. In NEN patients with a recent history of surgery, particularly involving the small intestine, this cause of diarrhea must be considered;

- Bile acid malabsorption (BAM) occurs when an excess of bile acids entering the colon causes signs and symptoms, including watery stool, urgency, and fecal incontinence. BAM is usually a diagnosis of exclusion of chronic diarrhea in patients with a history of resection of the terminal ileum and/or right colon or cholecystectomy [18];

- Antiproliferative treatments in patients with NEN include systemic chemotherapies, target therapies (sunitinib or everolimus), and SSA. All these treatments may cause GI adverse events including chronic diarrhea (sunitinib in up to 50%, everolimus in up to 30%, and SSA in around 20% of cases) [10];

- Other causes of diarrhea, which may be the only cause or coexist in a patient with NEN, include common etiologies such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [10,16,18], drugs or thyroid disfunction. IBS is a non-inflammatory functional syndrome that occurs in about 10–13% of the population and is characterized by constipation or diarrhea or both associated with abdominal pain or discomfort and bloating. In contrast to CS, IBS symptoms are usually intermittent, non-nocturnal, and not associated with weight loss and biochemical alterations; however, as a result of its prevalence, IBS should always be considered as a contributing factor of diarrhea in a patient NEN diagnosis. Coeliac disease (CD) occurs in about 0.5–1% of the general population and represents 3–10% of patients with chronic diarrhea. In the presence of watery diarrhea and other typical sign or symptoms of CD, such as iron deficiency anemia, osteoporosis, and an association with other autoimmune disorders (type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroiditis), a serological test must be performed [16]. Finally, in case of bloody, mucoid diarrhea, urgency, and systemic signs of inflammation, a calprotectin fecal test and colonoscopy with multiples biopsies must be performed to rule out a IBD diagnosis [18]. Moreover, as reported by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO), in the collaborative network for exceptionally rare case report project (CONFER) case series, NEN and IBD may concomitantly be diagnosed in the same patient with a favorable prognostic course [23]. Finally, other common etiologies, not related to gastrointestinal disease, should always be investigated, with particular attention paid to drug history and endocrinopathies (thyroid dysfunction, diabetes) [10,18].

Given the wide variety of etiologies involved in the occurrence of chronic diarrhea in a patient with an NEN diagnosis, it is important to pay particular attention to the physical examination, medical history and, above all, to think of the most common cause before the rarest.

3.2. Flushing

Flushing is defined as a sensation of warmth accompanied by erythema, usually involving the head, neck, and the chest and which typically occurs in episodic attacks. This symptom occurs in about 20–30% of the patients and may appear spontaneously or can be provoked by emotional stress, stimulation of the vagus nerve, and the ingestion of alcohol or tyramine-containing foods (e.g., cheese, coffee, chocolate, nuts, avocado, bananas, and red wine). However, flushing episodes are often not recognized by the patient; therefore, it is important to investigate this symptom with family members or friends, which usually notice them. Other common causes that may be confused with CS flushing are post-menopausal flushes, which are usually associated with sweating, prostatic cancer treatment involving medical or surgical castration in men, and drug-related flushes [14,24].

3.3. Liver Metastases

Since serotonin and other vasoactive substances produced by the tumor are usually inactivated by the liver, CS usually occurs when liver metastases are present (87–100% of patients), especially in NEN of the small intestine. In smaller percentages (5–13%), CS may present in the absence of liver involvement, particularly in patients with ovarian, testicular, or retroperitoneal metastases, or those with primary lung NEN [6,7]. In the absence of liver metastases, in fact, the bioactive amines are directly released into the systemic circulation via the internal vena cava or renal vein [9]. However, in a patient with a NEN diagnosis and no liver metastatic disease, other potential causes of diarrhea need to be ruled out before considering CS diagnosis, which might be present in a limited proportion of cases.

3.4. Carcinoid Heart Disease (CHD)

CHD is a severe complication of CS reported in 20–40% of these patients. It is caused by fibrotic damage to the heart, especially involving the right section. CHD is, in fact, most frequently characterized by tricuspid valve and pulmonary valve regurgitation and stenosis. However, in approximately one-third of patients, CHD may also affect the left-sided valves. Attention must be paid to fatigue and dyspnea; although over 50% of patients suffering from CHD are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic andthey may develop progressive symptoms together with signs of right-sided heart failure (such as elevated jugular venous pressure, hepatomegaly, peripheral oedema, or ascites). Therefore, when CS is suspected, it is mandatory to refer the patient to a cardiologist for a check-up including an echocardiogram [13]. Recently, the European Neuroendocrine Tumors Society (ENETS) Carcinoid Heart Disease Task Force published a practical guide and standardization for echocardiography in patients affected by neuroendocrine neoplasia and CHD to promote the homogeneous and detailed assessment of these patients [25].

3.5. 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic Acid Urine Collection

More than 40 secretory products that are possibly responsible for CS manifestations have been identified, including histamine, prostaglandins, and tachykinins; however, serotonin plays a key role in some of CS manifestations, such as diarrhea, carcinoid heart disease (CHD), and fibrosis [6,7]. 5-HIAA is the main metabolite of serotonin and it is the major biomarker used for diagnosis and follow-up. Twenty-four-hour urine collection for 5-HIAA shows a large variability in diagnostic accuracy, with an approximate 70% sensitivity and 90% specificity, which increases with small intestinal NEN. Moreover, urinary 5-HIAA correlates with tumor size and metastatic burden, whereas a correlation with clinical severity is not well established due to the variable release of serotonin from these tumors. It is crucial to avoid eating foods high in amines (avocado, chocolate, coffee, tea, nuts, etc.) at least three days before the exam to avoid false positive findings due to the release of bioactive amines. Rarely, CS may be not related to high levels of U-5-HIAA, because of the potential release of other biologically active substances [9].

The plasmatic measurement of serotonin (5-HT) has a high sensitivity even when small amounts of 5-HT are released by the tumor; however, low accuracy and reproducibility limits its use in clinical practice. Finally, there are promising results for plasma fasting 5-HIAA measurements, which seems to correlate with U-5-HIAA with a high accuracy; however, more prospective studies are needed to validate this [9].

In conclusion, to date, twenty-four-hour urine collection for 5-HIAA remains the only diagnostic tool for the diagnosis and follow-up of CS.

3.6. Nutritional Status

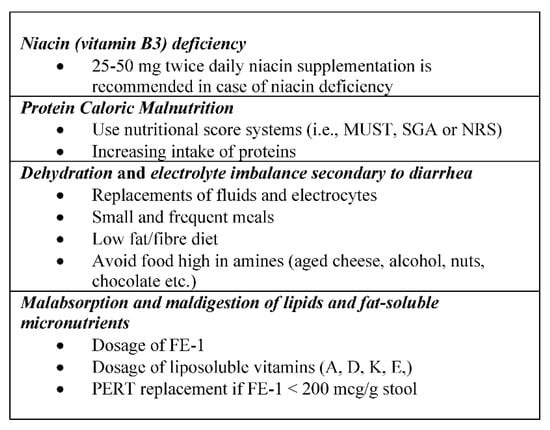

In patients with NEN and CS, nutritional status may be impaired by several factors (Figure 2) and the main nutritional deficiencies, occurring in about 14–38% of patients, involve vitamins (niacin, vitamin A, D, K, E) and proteins [26].

Figure 2.

Key points of nutritional status in patients with carcinoid syndrome (CS). MUST: malnutritional universal screening tool; SGA: subjective global assessment; NRS: nutritional risk screening; FE-1: fecalelastase 1; PERT: pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.

Niacin (vit B3) deficiency is the most frequent alteration related to CS; however, it is often underestimated in clinical practice. In patients with serotonin producing NEN, 60% of the tryptophan pool is consumed for serotonin synthesis by the tumor itself, leading to an important protein and niacin (vitamin B3) depletion that is present in about 45% of patients with CS [27]. Because of niacin deficiency, patients may develop neurocognitive symptoms and pellagra characterized by dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia. Moreover, it is estimated that up to 80% of patients with CS die soon after the identification of pellagra; thus, early recognition and prompt supplementation of niacin deficiency are crucial in these patients [26]. More interventional clinical studies are needed to define the optimal treatment for niacin deficiency; however, the Carcinoid Cancer Foundation recommends 25–50 mg niacin supplementation twice daily for patients with CS, especially in the presence of a documented niacin deficiency [28]. The depletion of tryptophan in these patients is also responsible for protein-caloric malnutrition, which also contributes reduced food intake, loss of appetite secondary to the tumor itself, complications related to diarrhea, and potential side-effects of systemic anti-tumor therapies [29].

As mentioned before, diarrhea is the most common symptom of CS, occurring in about 80% of patients [6,7]. There are several nutritional factors to consider in a patient with chronic diarrhea; first, water and fluid intake are crucial to prevent dehydration and electrolyte imbalance (i.e., hypokalemia). Replacement of fluids and electrocytes (potassium) are recommended in these patients [30]. A low-fiber diet, particularly increasing soluble fibers and reducing insoluble fibers, is also considered an integral part of the management of chronic diarrhea [29,30]. Moreover, small and frequent meals with a low fat content are advised. In the presence of CS, foods that are high in amines, such as aged cheese, alcohol, nuts, chocolate, and smoked fish or meat, must be avoided, given their ability to trigger diarrhea and other symptoms (flushing) of CS [28,29,30]. Another important factor that may influence the nutritional status of these patients is pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) secondary to the chronic use of SSA. These drugs are, in fact, particularly used in the setting of patients with NEN and carcinoid syndrome to both control symptoms and inhibit tumor growth [31,32]. The development of PEI, which occurs in up to 20% of patients treated with SSA [20], determines malabsorption and maldigestion of lipids and fat-soluble micronutrients, leading to steatorrhea, weight loss, and deficiency of liposoluble vitamins (A, D, K, E,) [15]. A nutritional assessment in case of suspected PEI should include vitamins dosage (A, D, K, E), serum calcium, parathyroid hormone, and glycate hemoglobin. In addition to the clinical evaluation, the assessment of fecal elastase-1 (FE-1) is mandatory for the diagnosis: a value of FE-1 below 200 mcg/g stool is suggestive of PEI, which is considered severe when values are below 100 mcg/g stool [19]. If exocrine pancreatic disfunction is detected, pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) at a standard dose (40.000 PhU with each main meal) should be immediately started [20].

In general, malnutrition is known to have a negative impact on clinical outcomes in terms of overall survival (OS), quality of life, and response to anti-tumor treatments in patients with cancer. However, despite the increasing awareness of the importance of clinical nutrition in cancer patients, as encouraged by the international guidelines, malnutrition remains underestimated and untreated in about 50% of patients with cancer [33]. Specifically, it has been demonstrated that malnutrition in NEN patients is associated with a higher risk of complications, mortality, a shorter overall survival, and longer length of hospital stay [26]. Therefore, an early clinical nutritional assessment using specific score systems (i.e., MUST, SGA, or NRS) should be performed in all patients with NEN at diagnosis and during follow-up, particularly in the presence of additional risk factors for nutritional alterations (i.e., diarrhea in CS, concomitant treatment with SSA) [29].

4. Treatment of Diarrhea in a Patient with CS

The goal of systemic therapy in patients affected by NEN and CS is to control both hormone symptoms and tumor growth.

- Somatostatin analogues (SSA): SSA are a common first-line therapy in well-differentiated functional tumors to both control symptoms related to the syndrome and tumor growth [31,32].

Their inhibitory effect is exercised by binding and activating the G protein-coupled receptors (somatostatin receptors 1 to 5 (SSTR 1–5)), whereas the anti-proliferative activity is predominantly mediated by binding to SSTR subtype 2 expressed on the tumor cells, or indirectly affecting tumor proliferation by the inhibition of angiogenesis and immunomodulation. There are two commercially available formulations: short acting octreotide, administered subcutaneously three times a day, and octreotide long-acting release (octreotide LAR) or octreotide autogel given every 28 days at a dose of 30 mg and 120 mg, respectively [6]. Both formulations are effective to achieve symptom control, with an improvement of flushing and diarrhea reported in 70–80% of patients. Moreover, they are well tolerated with minor transient gastrointestinal side effects (diarrhea, flatulence, abdominal discomfort, nausea) [6,34]. In case of worsening of CS symptoms, it is common practice to increase the standard dose of SSA by reducing the injection interval at 3 or 2 weeks or with a dose escalation [35]. The CLARINET FORTE phase-2 clinical trial provided encouraging results regarding PFS in patients with progressive NEN treated with lanreotide autogel 120 mg given at an interval of 14 days instead of the standard 28 days; however, data on symptom control are scarce due to the small percentage of patients with CS included [36]. However, a recent metanalysis [15] showed that both dose escalation and reduced interval of administration are effective in hormonal syndrome control, resulting in a reduction in diarrhea in 72% of patients and flushing episodes in 84% of patients. Finally, in some cases, a rescue octreotide s.c. injection is necessary for uncontrolled symptoms.

- Interferon alfa (IFN- α): IFN- α has shown both antiproliferative anti-hormonal activity in patients with CS and is approved for symptom control at a dose of 3–5 million IU s.c. three times weekly as a second line option in patients with a refractory syndrome. Even if its efficacy is similar compared to SSA, the low tolerability due to its side effects (e.g., flu-like symptoms, chronic fatigue, liver and bone marrow toxicity) has limited its use in clinical practice [1,34];

- Telotristrat ethyl: Telotristat ethyl is an oral inhibitor of tryptophan hydroxylase, the key enzyme in serotonin synthesis, and is approved for the treatment of diarrhea in patients that are not controlled by SSA therapy [34]. Two phase III placebo-controlled trials (TELESTAR and TELECAST) [37,38] support the efficacy and good tolerability of Telotristat ethyl, which reduced bowel movements in 42–44% (TELESTAR) of patients and improved quality of life; however, no significant relief of flushing was described. Adverse events were reported to include mild elevation of liver enzymes and depression and nausea were described at higher doses [34];

- Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT): In progressive small intestine NEN, PRRT may be considered to improve hormonal symptoms, probably due to its cytoreductive effect. The targets of PRRT are the somatostatin receptors, which are overexpressed by these tumors and bind radiolabeled somatostatin analogues (90 Yttrium or 177 Lutetium). The open-label multicenter phase III clinical trial NETTER-1 showed that 177 Lutetium (177Lu) Dotate therapy prolongs progression-free survival (PFS) compared to high-dose octreotide alone [39]. With regard to the improvement of diarrhea in patients with CS, in the NETTER-1 trial, there were no significant difference between the two arms; however, a delay in deterioration of quality-of-life scores in patients receiving PRRT was showed compared with the high-dose somatostatin analogue alone [39]. Data on the efficacy of PRRT on refractory CS without evidence of radiological progressive disease are still scarce. A metanalysis of 156 patients with CS treated with radionuclide therapy (90 Yttrium or 177 Lutetium) selected from four prospective phase-2, single center studies showed a symptomatic relief in 74% of 47 patients with diarrhea and in 64% of 56 patients with flushing [15]. Finally, care should be taken concerning the risk of acute aggravation of diarrhea reported in some patients treated with radionuclide therapy [34];

- Everolimus: Everolimus is an oral inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) that has been shown to have an antiproliferative effect, which led to its approval in the treatment of NEN of pancreatic, lung, and intestinal origin [40,41,42]. However, the use of everolimus in patients with NEN and CS is still unclear. Even if the RADIANT-2 trial showed an improved progression-free survival (PFS) in the everolimus arm compared to the octreotide alone, this difference was not statistically significant, and no improvement in overall survival (OS) was observed with everolimus [41]. Thus, everolimus is not registered for use in functional NEN [34];

- Liver-directed therapy: Liver-directed therapies are indicated in functional NEN for both tumor volume reduction and symptom control and include surgical cytoreduction, radiofrequency ablation, selective internal radiotherapy, bland embolization, and chemoembolization. Surgical resection is usually indicated in case of resectable liver disease to achieve long-term disease-free survival and improvement of CS symptoms [6,34]. For advanced functional NEN, all these loco-regional therapies showed promising results; however, there is low-quality evidence concerning this approach and data are mainly derived from uncontrolled retrospective single institutional series. When combining different liver-directed techniques, an overall symptoms response was achieved in 82% of patients, whereas U-5-HIAA levels were reduced in 61% of patients [15]. Finally, for selected patients with a resected primary tumor and oligo-metastatic liver disease, liver transplantation may be considered [6];

- Debulking surgery: In advanced metastatic functional small intestinal NEN, debulking surgery is a treatment option and is recommended to improve symptoms related to CS and symptoms related to tumor burden [34]. However, randomized, controlled studies to support debulking surgery are lacking and evidence is often derived from small retrospective series reports [6,34].

Particular attention must be paid to prevent a carcinoid crisis in patients with CS undergoing invasive procedures. A carcinoid crisis is a potentially life-threatening complication of CS caused by the sudden release of serotonin and other vasoactive substances from the tumor. Clinically, it is characterized by severe flushing, bronchospasm, arrhythmia, and hemodynamic instability. Thus, prophylactic administration of intravenous (IV) octreotide is recommended for patients with CS undergoing invasive procedures (e.g., surgery, liver-directed therapies), PRRT, or anesthesia [6,14].

Even if a broad spectrum of possible therapeutic options is available in the setting of a patient with CS, SSA remain the first line choice in these patients. However, after failure of SSA, a clear treatment algorithm is lacking; thus, early referral to a NEN-dedicated center is advised in order to provide these patients the possibility of a multidisciplinary therapeutic approach to improve patient clinical outcome [43].

5. Conclusions

Carcinoid syndrome is the most common NEN functional syndrome and is caused by the release of serotonin and other vasoactive substances. It commonly occurs in small intestine NEN with extensive liver metastases. Given the variety of the clinical presentation, diagnosis is still challenging; notably, when diarrhea is present in a NEN patient, several hypotheses should be investigated before considering a functional cause related to CS. In fact, only a minority of NEN patients present CS, which needs to be confirmed after exploring other signs and symptoms, such as flushing, asthma-like symptoms, tumor primary site, the presence of liver metastases, heart disease, and high levels of 5-HIAA. A broad spectrum of possible therapeutic options is available to control symptoms related to CS, but SSA remain the mainstay of treatment in these patients. Finally, a nutritional assessment must be included in the diagnostic work-up of patients with CS, with particular attention paid to niacin deficiency, protein malnutrition, dehydration, electrocytes imbalance, and fat-soluble micronutrients.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to this review, in terms of drafting, revising, and finally approving the version to be published. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cives, M.; Strosberg, J.R. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epidemiology, Incidence, and Prevalence of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Are There Global Differences? Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 23, 43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasari, A.; Shen, C.; Halperin, D.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Y.; Shih, T.; Yao, J.C. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzuto, F.; Cicchese, N.; Partelli, S.; Rinzivillo, M.; Capurso, G.; Merola, E.; Manzoni, M.; Pucci, E.; Iannicelli, E.; Pilozzi, E.; et al. Impact of Ki67 re-assessment at time of disease progression in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magi, L.; Rinzivillo, M.; Panzuto, F. Tumor heterogeneity in gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasia. Endocrines 2021, 2, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleinikov, K.; Avniel-Polak, S.; Gross, D.J.; Grozinsky-Glasberg, S. Carcinoid Syndrome: Updates and Review of Current Therapy. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2019, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Lee, L.; Jensen, R.T. Carcinoid-syndrome: Recent advances, current status and controversies. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2018, 25, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, D.M.; Shen, C.; Dasari, A.; Xu, Y.; Chu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Shih, Y.T.; Yao, J.C. Frequency of carcinoid syndrome at neuroendocrine tumour diagnosis: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanciulli, G.; Ruggeri, R.M.; Grossrubatscher, E.; Calzo, F.L.; Wood, T.D.; Faggiano, A.; Isidori, A.; Colao, A. Serotonin pathway in carcinoid syndrome: Clinical, diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic implications. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusceddu, S.; Rossi, R.E.; Torchio, M.; Prinzi, N.; Niger, M.; Coppa, J.; Giacomelli, L.; Sacco, R.; Facciorusso, A.; Corti, F.; et al. Differential Diagnosis and Management of Diarrhea in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederle, B.; Pape, U.F.; Costa, F.; Gross, D.; Kelestimur, F.; Knigge, U.; Öberg, K.; Pavel, M.; Perren, A.; Toumpanakis, C.; et al. Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Jejunum and Ileum. Neuroendocrinology 2016, 103, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koumarianou, A.; Alexandraki, K.I.; Wallin, G.; Kaltsas, G.; Daskalakis, K. Pathogenesis and Clinical Management of Mesenteric Fibrosis in Small Intestinal Neuroendocine Neoplasms: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Sharma, A.N.; Thevakumar, B.; Majid, M.; Al Chalaby, S.; Takahashi, N.; Tanious, A.; Arockiam, A.D.; Beri, N.; Amsterdam, E.A. Carcinoid Heart Disease: Pathophysiology, Pathology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management. Cardiology 2021, 146, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, D.; Ramage, J.; Srirajaskanthan, R. Update on Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Complications of Carcinoid Syndrome. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 8341426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofland, J.; Herrera-Martínez, A.D.; Zandee, W.T.; de Herder, W.W. Management of carcinoid syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2019, 26, R145–R156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arasaradnam, R.P.; Brown, S.; Forbes, A.; Fox, M.R.; Hungin, P.; Kelman, L.; Major, G.; O’Connor, M.; Sanders, D.S.; Sinha, R.; et al. Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea in adults: British Society of Gastroenterology, 3rd ed. Gut 2018, 67, 1380–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulke, M.H.; Shah, M.H.; Benson, A.B., 3rd; Bergsland, E.; Berlin, J.D.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; Emerson, L.; Engstrom, P.F.; Fanta, P.; Giordano, T.; et al. Neuroendocrine Tumors, Version 1.2015. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2015, 13, 78–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eads, J.R.; Reidy-Lagunes, D.; Soares, H.P.; Chan, J.A.; Anthony, L.B.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Naraev, B.G.; Wolin, E.M.; Halperin, D.M.; Li, D.; et al. From the Carcinoid Syndrome Control Collaborative. Differential Diagnosis of Diarrhea in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas 2020, 49, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinzivillo, M.; De Felice, I.; Magi, L.; Annibale, B.; Panzuto, F. Occurrence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors treated with somatostatin analogs. Pancreatology 2020, 20, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzuto, F.; Magi, L.; Rinzivillo, M. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and somatostatin analogs in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasia. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 20, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeejeebhoy, K.N. Short bowel syndrome: A nutritional and medical approach. CMAJ 2002, 166, 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nightingale, J.; Woodward, J.M. Small Bowel and Nutrition Committee of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for management of patients with a short bowel. Gut 2006, 55 (Suppl. 4), iv1–iv12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festa, S.; Zerboni, G.; Derikx, L.A.A.P.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Dragoni, G.; Buskens, C.; van Dijkum, E.N.; Pugliese, D.; Panzuto, F.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I.; et al. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An ECCO CONFER Multicentre Case Series. J. Crohns Colitis. 2021, 20, jjab217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguet, I.; Grossman, A. Management of Endocrine Disease: Flushing: Current concepts. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 177, R219–R229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hofland, J.; Lamarca, A.; Steeds, R.; Toumpanakis, C.; Srirajaskanthan, R.; Riechelmann, R.; Panzuto, F.; Frilling, A.; Denecke, T.; Christ, E.; et al. ENETS Carcinoid Heart Disease Task Force. Synoptic reporting of echocardiography in carcinoid heart disease (ENETS Carcinoid Heart Disease Task Force). J. Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 33, e13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, E.; Kiss, N.; Michael, M.; Krishnasamy, M. Nutritional Complications and the Management of Patients with Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2020, 110, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, G.; van Faassen, M.; Kats-Ugurlu, G.; de Vries, E.G.; Kema, I.P.; Walenkamp, A.M. Niacin (Vitamin B3) Supplementation in Patients with Serotonin-Producing Neuroendocrine Tumor. Neuroendocrinology 2016, 103, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Carcinoid Cancer Foundation. Available online: https://www.carcinoid.org/for-patients/general-information/nutrition/nutritional-concerns-for-the-carcinoid-patient-developing-nutrition-guidelines-for-persons-with-carcinoid-disease/ (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Artale, S.; Barzaghi, S.; Grillo, N.; Maggi, C.; Lepori, S.; Butti, C.; Bovio, A.; Barbarini, L.; Colombo, A.; Zanlorenzi, L.; et al. Role of Diet in the Management of Carcinoid Syndrome: Clinical Recommendations for Nutrition in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors. Nutr. Cancer. 2020, 74, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M.; Muscogiuri, G.; Pizza, G.; Ruggeri, R.M.; Barrea, L.; Faggiano, A.; Colao, A.; NIKE Group. The management of neuroendocrine tumours: A nutritional viewpoint. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, A.; Wittenberg, M.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; Aminossadati, B.; Ronicke, E.; Gress, T.M.; Müller, H.H.; Arnold, R.; PROMID Study Group. Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Prospective, Randomized Study on the Effect of Octreotide LAR in the Control of Tumor Growth in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Midgut Tumors (PROMID): Results of Long-Term Survival. Neuroendocrinology 2017, 104, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplin, M.E.; Pavel, M.; Ćwikła, J.B.; Phan, A.T.; Raderer, M.; Sedláčková, E.; Cadiot, G.; Wolin, E.M.; Capdevila, J.; CLARINET Investigators; et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caccialanza, R.; Goldwasser, F.; Marschal, O.; Ottery, F.; Schiefke, I.; Tilleul, P.; Zalcman, G.; Pedrazzoli, P. Unmet needs in clinical nutrition in oncology: A multinational analysis of real-world evidence. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835919899852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavel, M.; Öberg, K.; Falconi, M.; Krenning, E.P.; Sundin, A.; Perren, A.; Berruti, A.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: Clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 844–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broder, M.S.; Beenhouwer, D.; Strosberg, J.R.; Neary, M.P.; Cherepanov, D. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors treated with high dose octreotide-LAR: A systematic literature review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 1945–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavel, M.; Ćwikła, J.B.; Lombard-Bohas, C.; Borbath, I.; Shah, T.; Pape, U.F.; Capdevila, J.; Panzuto, F.; Truong Thanh, X.M.; Houchard, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of high-dose lanreotide autogel in patients with progressive pancreatic or midgut neuroendocrine tumours: CLARINET FORTE phase 2 study results. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 157, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulke, M.H.; Hörsch, D.; Caplin, M.E.; Anthony, L.B.; Bergsland, E.; Öberg, K.; Welin, S.; Warner, R.R.; Lombard-Bohas, C.; Kunz, P.L.; et al. Telotristat Ethyl, a Tryptophan Hydroxylase Inhibitor for the Treatment of Carcinoid Syndrome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavel, M.; Gross, D.J.; Benavent, M.; Perros, P.; Srirajaskanthan, R.; Warner, R.R.P.; Kulke, M.H.; Anthony, L.B.; Kunz, P.L.; Hörsch, D.; et al. Telotristat ethyl in carcinoid syndrome: Safety and efficacy in the TELECAST phase 3 trial. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2018, 25, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strosberg, J.; El-Haddad, G.; Wolin, E.; Hendifar, A.; Yao, J.; Chasen, B.; Mittra, E.; Kunz, P.L.; Kulke, M.H.; Jacene, H.; et al. NETTER-1 Trial Investigators. Phase 3 Trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; Shah, M.H.; Ito, T.; Bohas, C.L.; Wolin, E.M.; Van Cutsem, E.; Hobday, T.J.; Okusaka, T.; Capdevila, J.; de Vries, E.G.; et al. RAD001 in Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumors, Third Trial (RADIANT-3) Study Group. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.E.; Hainsworth, J.D.; Baudin, E.; Peeters, M.; Hörsch, D.; Winkler, R.E.; Klimovsky, J.; Lebwohl, D.; Jehl, V.; Wolin, E.M.; et al. Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable for the treatment of advanced neuroendocrine tumours associated with carcinoid syndrome (RADIANT-2): A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet 2011, 378, 2005–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; Fazio, N.; Singh, S.; Buzzoni, R.; Carnaghi, C.; Wolin, E.; Tomasek, J.; Raderer, M.; Lahner, H.; Voi, M.; et al. RAD001 in Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumours, Fourth Trial (RADIANT-4) Study Group. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, non-functional neuroendocrine tumours of the lung or gastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet 2016, 387, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magi, L.; Mazzuca, F.; Rinzivillo, M.; Arrivi, G.; Pilozzi, E.; Prosperi, D.; Iannicelli, E.; Mercantini, P.; Rossi, M.; Pizzichini, P.; et al. Multidisciplinary Management of Neuroendocrine Neoplasia: A Real-World Experience from a Referral Center. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).