Mayo Endoscopic Score and Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index Are Equally Effective for Endoscopic Activity Evaluation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients in a Real Life Setting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Videos

2.2. Evaluation

2.3. Statistics

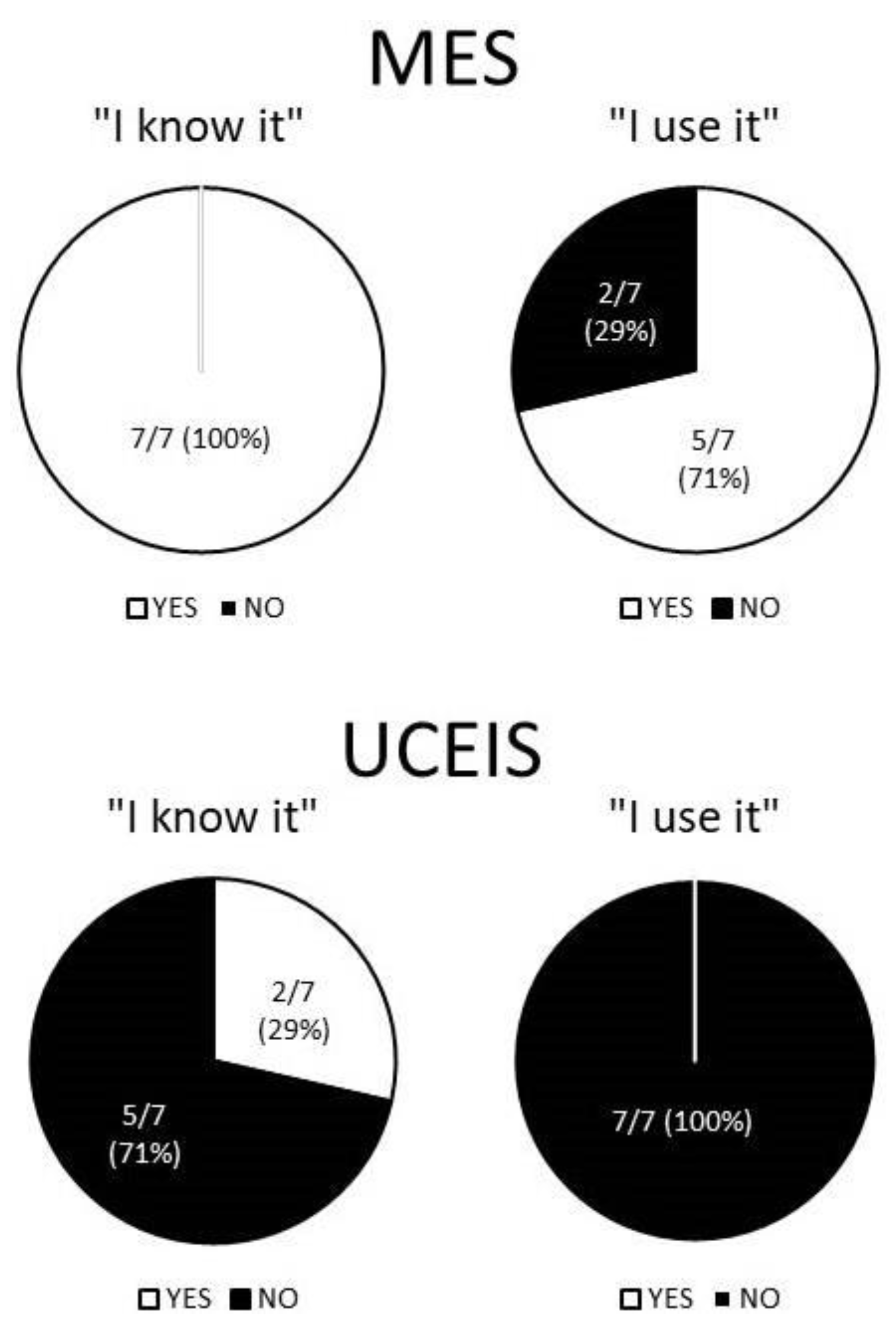

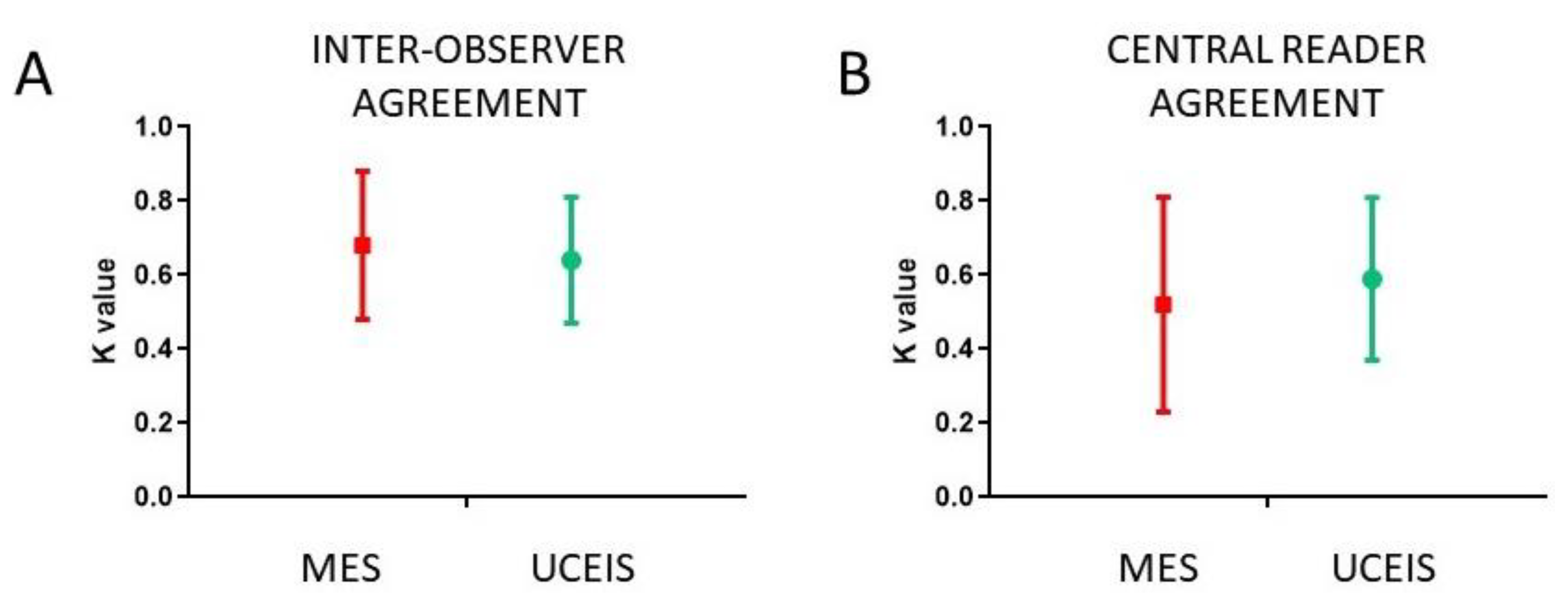

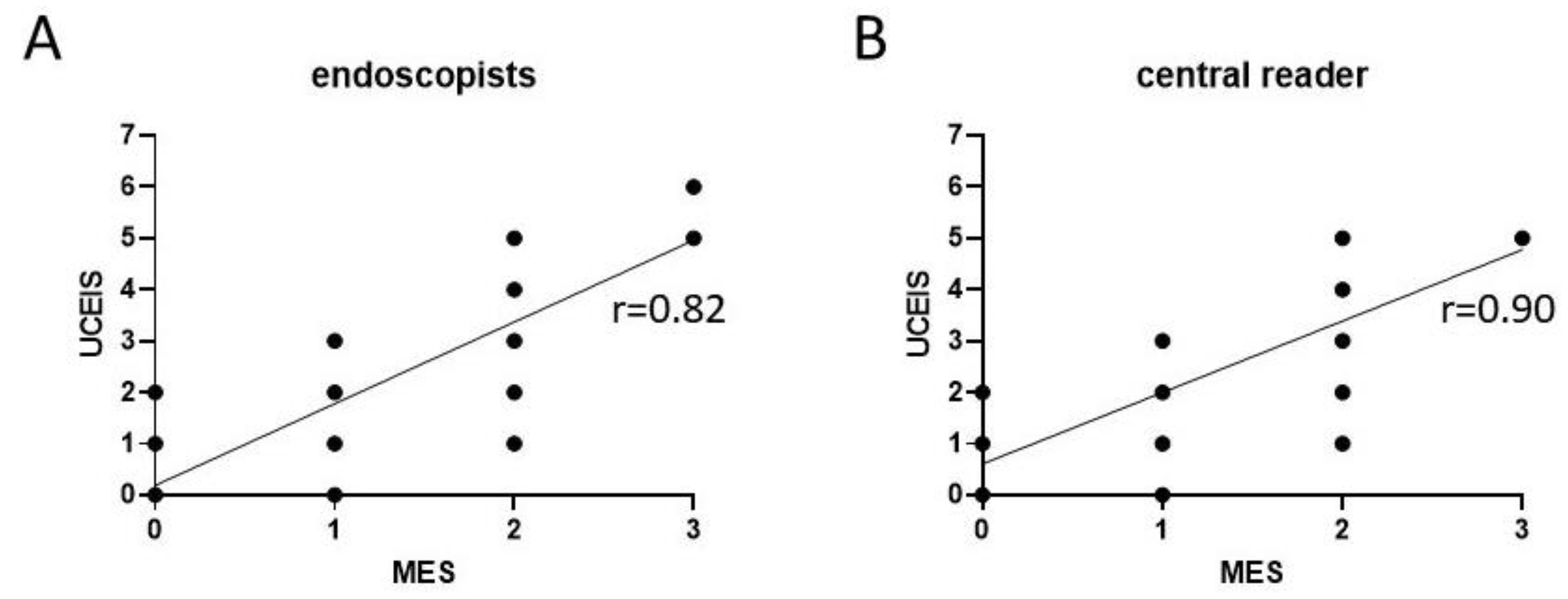

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ordas, I.; Eckmann, L.; Talamini, M.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sandborn, W.J. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2012, 380, 1606–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.D.; Ponder, A. A clinical review of recent findings in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 5, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Paolo, M.C.; Pagnini, C.; Graziani, M.G. Corticosteroids in Inflammatory Bowel Disease patients: A practical guide for physicians. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, S.C.; Witts, L.J. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br. Med. J. 1955, 2, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombel, J.F.; Rutgeerts, P.; Reinisch, W.; Esser, D.; Wang, Y.; Lang, Y.; Marano, C.W.; Strauss, R.; Oddens, B.J.; Feagan, B.G.; et al. Early Mucosal Healing With Infliximab Is Associated With Improved Long-term Clinical Outcomes in Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardizzone, S.; Maconi, G.; Russo, A.; Imbesi, V.; Colombo, E.; Porro, G.B. Randomised controlled trial of azathioprine and 5-aminosalicylic acid for treatment of steroid dependent ulcerative colitis. Gut 2006, 55, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M.D.; Saunders, B.P.; Wilkinson, K.H.; Rumbles, S.; Schofield, G.; Kamm, M.; Williams, C.B.; Price, A.B.; Talbot, I.C.; Forbes, A. Cancer surveillance in longstanding ulcerative colitis: Endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut 2004, 53, 1813–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagan, B.G.; Sandborn, W.J.; D’Haens, G.; Pola, S.; McDonald, J.W.; Rutgeerts, P.; Munkholm, P.; Mittmann, U.; King, D.; Wong, C.J.; et al. The Role of Centralized Reading of Endoscopy in a Randomized Controlled Trial of Mesalamine for Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 149–157.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, C.; Menasci, F.; Desideri, F.; Corleto, V.D.; Fave, G.D.; Di Giulio, E. Endoscopic scores for inflammatory bowel disease in the era of ‘mucosal healing’: Old problem, new perspectives. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schroeder, K.W.; Tremaine, W.J.; Ilstrup, D.M. Coated Oral 5-Aminosalicylic Acid Therapy for Mildly to Moderately Active Ulcerative Colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, S.P.L.; Schnell, D.; Krzeski, P.; Abreu, M.T.; Altman, D.G.; Colombel, J.-F.; Feagan, B.G.; Hanauer, S.B.; Lémann, M.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; et al. Developing an instrument to assess the endoscopic severity of ulcerative colitis: The Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS). Gut 2012, 61, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeya, K.; Hanai, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Osawa, S.; Kawasaki, S.; Iida, T.; Maruyama, Y.; Watanabe, F. The Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity More Accurately Reflects Clinical Outcomes and Long-term Prognosis than the Mayo Endoscopic Score. J. Crohns Colitis 2016, 10, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, C.; Mariani, B.M.; Lorenzetti, R. Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity is Feasible and Useful for Evaluation of Endoscopic Activity in Ulcerative Colitis Patients in a Real-life Setting. J. Crohns Colitis 2018, 12, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, S.P.; Schnell, D.; Krzeski, P.; Abreu, M.T.; Altman, D.G.; Colombel, J.; Feagan, B.G.; Hanauer, S.B.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Marteau, P.R.; et al. Reliability and Initial Validation of the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Vashist, N.; Samaan, M.; Mosli, M.H.; Parker, C.E.; MacDonald, J.K.; Nelson, S.A.; Zou, G.Y.; Feagan, B.G.; Khanna, R.; Jairath, V. Endoscopic scoring indices for evaluation of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1, CD011450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daperno, M.; Comberlato, M.; Bossa, F.; Biancone, L.; Bonanomi, A.G.; Cassinotti, A.; Cosintino, R.; Lombardi, G.; Mangiarotti, R.; Papa, A.; et al. Inter-observer agreement in endoscopic scoring systems: Preliminary report of an ongoing study from the Italian Group for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD). Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daperno, M.; Comberlato, M.; Bossa, F.; Armuzzi, A.; Biancone, L.; Bonanomi, A.G.; Cosintino, R.; Lombardi, G.; Mangiarotti, R.; Papa, A.; et al. Training Programs on Endoscopic Scoring Systems for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Lead to a Significant Increase in Interobserver Agreement among Community Gastroenterologists. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, jjw181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.B.; Hergueta-Delgado, P.; Rodríguez, B.G.; Pérez, B.M.; Laria, L.C.; Rodríguez-Téllez, M.; Barroso, M.L.M.; Fernández, M.D.G.; Veloz, M.G.; García, V.A.J.; et al. Comparison of the Mayo Endoscopy Score and the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopy Index of Severity and the Ulcerative Colitis Colonoscopy Index of Severity. Endosc. Int. Open 2021, 9, E130–E136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ruscio, M.; Variola, A.; Vernia, F.; Lunardi, G.; Castelli, P.; Bocus, P.; Geccherle, A. Role of Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) versus Mayo Endoscopic Subscore (MES) in Predicting Patients’ Response to Biological Therapy and the Need for Colectomy. Digestion 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Zhang, T.; Ding, C.; Dai, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wei, Y.; Gong, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, J. Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) versus Mayo Endoscopic Score (MES) in guiding the need for colectomy in patients with acute severe colitis. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 6, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corte, C.; Fernandopulle, N.; Catuneanu, A.M.; Burger, D.; Cesarini, M.; White, L.; Keshav, S.; Travis, S. Association Between the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) and Outcomes in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 2015, 9, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, M.; Naganuma, M.; Sugimoto, S.; Kiyohara, H.; Ono, K.; Mori, K.; Saigusa, K.; Nanki, K.; Mutaguchi, M.; Mizuno, S.; et al. The Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity is Useful to Predict Medium- to Long-Term Prognosis in Ulcerative Colitis Patients with Clinical Remission. J. Crohns Colitis 2016, 10, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Kedia, S.; Bopanna, S.; Sachdev, V.; Sahni, P.; Dash, N.R.; Pal, S.; Vishnubhatla, S.; Makharia, G.; Travis, S.P.L.; et al. Faecal Calprotectin and UCEIS Predict Short-term Outcomes in Acute Severe Colitis: Prospective Cohort Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Mayo Endoscopic Score (MS) | Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Discrete (4 classes) | Continuous |

| Variables | Mucosal lesions, bleeding and hyperaemia | Mucosal lesions, vasculature, bleeding |

| Range | 0–4 | 0–8 |

| Mucosal healing | Score 0–1 | Not specified |

| Severe disease | Score 3 | Score ≥ 7 |

| Statistical validation | Partial | Partial |

| Used in trials | Yes | Scant |

| Diffuse in clinical practice | Yes | No |

| Strength | Simple, diffuse | Objective, prognostic value |

| Limitation | Subjective, imperfect agreement | More complex |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagnini, C.; Di Paolo, M.C.; Mariani, B.M.; Urgesi, R.; Pallotta, L.; Vitale, M.A.; Villotti, G.; d’Alba, L.; De Cesare, M.A.; Di Giulio, E.; et al. Mayo Endoscopic Score and Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index Are Equally Effective for Endoscopic Activity Evaluation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients in a Real Life Setting. Gastroenterol. Insights 2021, 12, 217-224. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent12020019

Pagnini C, Di Paolo MC, Mariani BM, Urgesi R, Pallotta L, Vitale MA, Villotti G, d’Alba L, De Cesare MA, Di Giulio E, et al. Mayo Endoscopic Score and Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index Are Equally Effective for Endoscopic Activity Evaluation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients in a Real Life Setting. Gastroenterology Insights. 2021; 12(2):217-224. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent12020019

Chicago/Turabian StylePagnini, Cristiano, Maria Carla Di Paolo, Benedetta Maria Mariani, Riccardo Urgesi, Lorella Pallotta, Mario Alessandro Vitale, Giuseppe Villotti, Lucia d’Alba, Maria Assunta De Cesare, Emilio Di Giulio, and et al. 2021. "Mayo Endoscopic Score and Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index Are Equally Effective for Endoscopic Activity Evaluation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients in a Real Life Setting" Gastroenterology Insights 12, no. 2: 217-224. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent12020019

APA StylePagnini, C., Di Paolo, M. C., Mariani, B. M., Urgesi, R., Pallotta, L., Vitale, M. A., Villotti, G., d’Alba, L., De Cesare, M. A., Di Giulio, E., & Graziani, M. G. (2021). Mayo Endoscopic Score and Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index Are Equally Effective for Endoscopic Activity Evaluation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients in a Real Life Setting. Gastroenterology Insights, 12(2), 217-224. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent12020019