The Diagnostic Pitfalls in the Pronator Teres Syndrome—A Case Report

Abstract

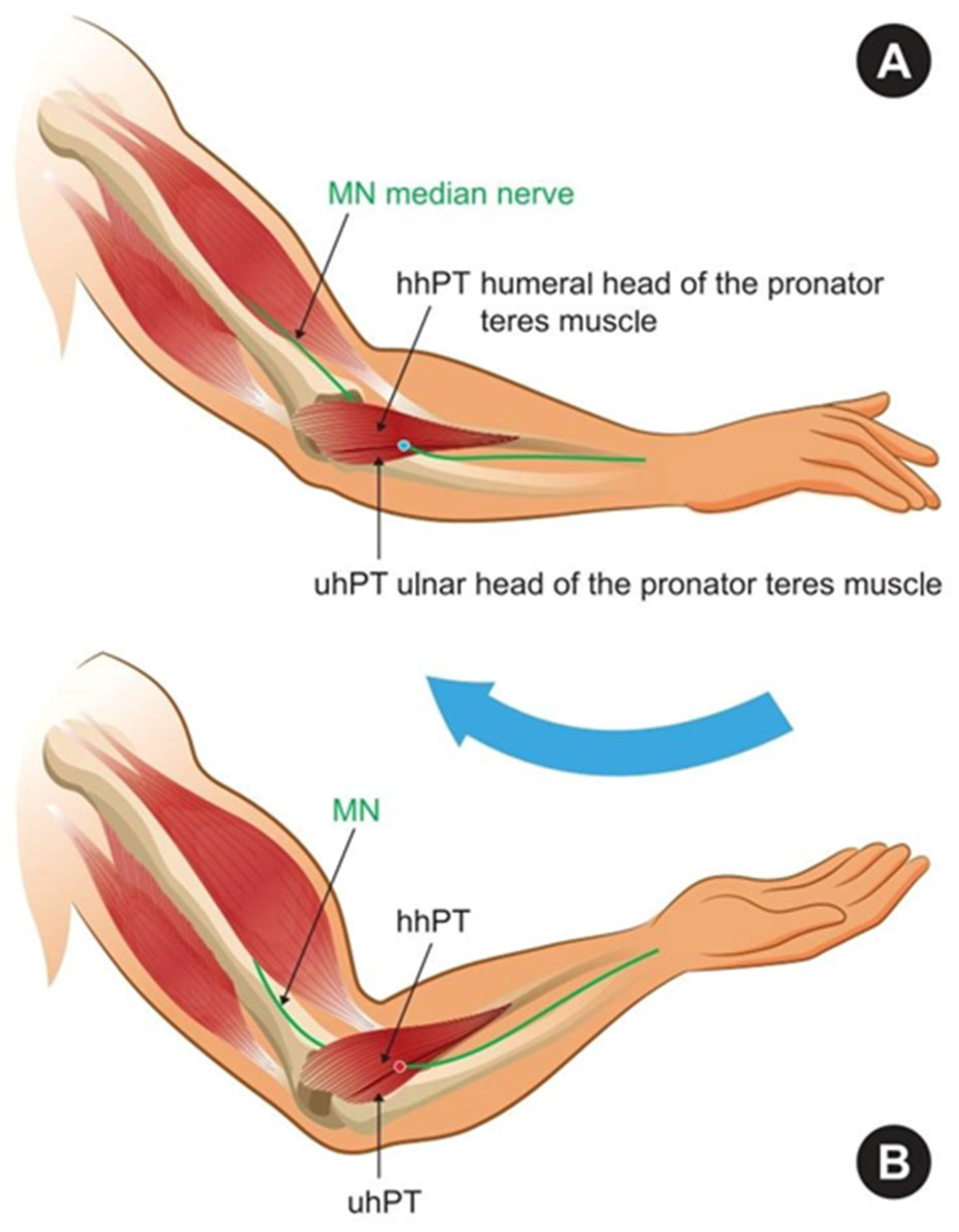

1. Introduction

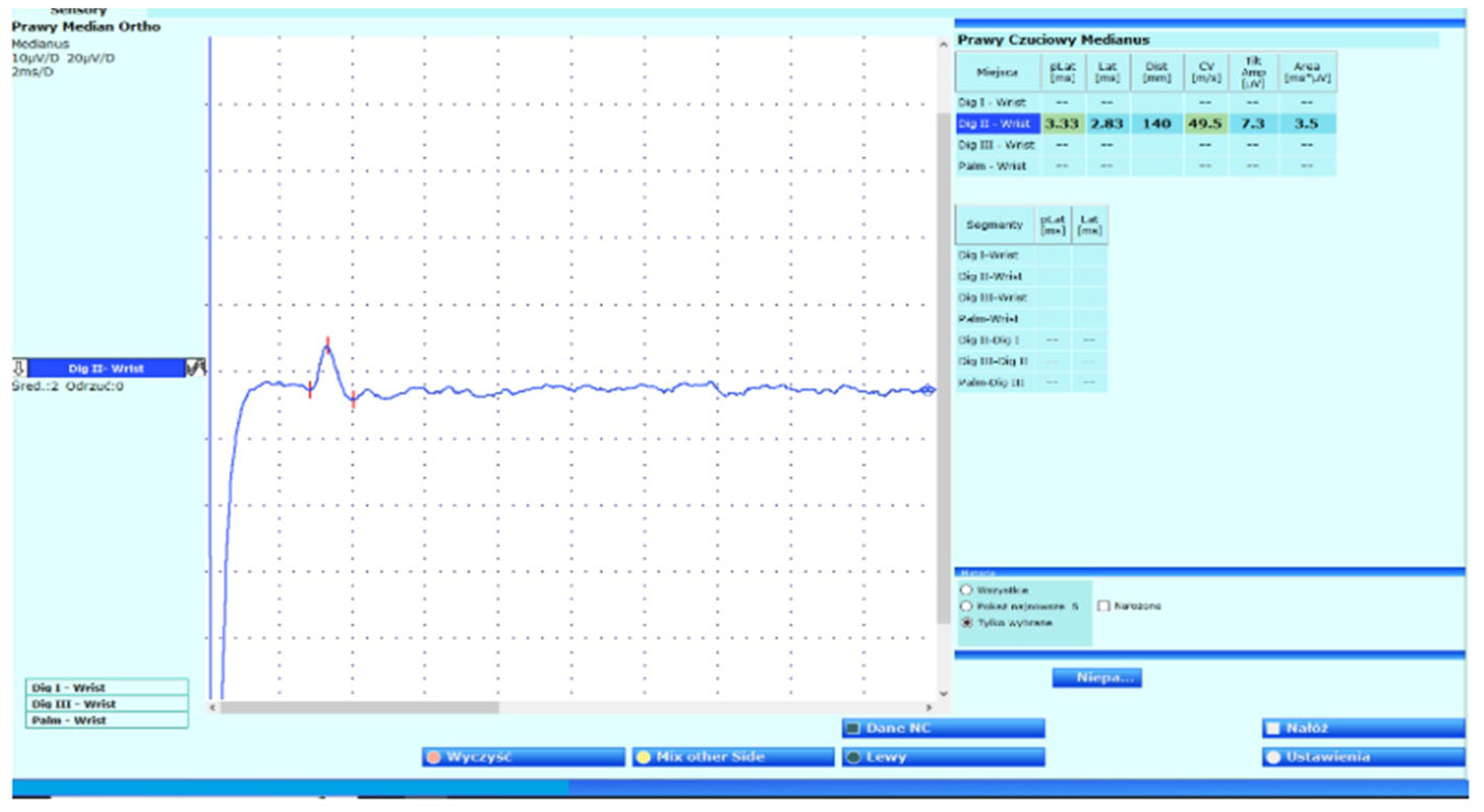

2. Case Report

3. Summary

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| AINS | Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome |

| APB | Abductor Pollicis Brevis |

| CTS | Carpal Tunnel Syndrome |

| DOMS | Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness |

| EIMD | Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| FDS | Flexor Digitorum Superficialis |

| FDP | Flexor Digitorum Profundus |

| FPL | Flexor Pollicis Longus |

| PT | Pronator Teres Muscle |

| PTS | Pronator Teres Syndrome |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

References

- Dididze, M.; Tafti, D.; Sherman, A.L. Pronator Teres Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, B.E.; Preston, D.C. Entrapment and compressive neuropathies. Med. Clin. North. Am. 2009, 93, 285–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodner, C.M.; Tinsley, B.A.; O’Malley, M.P. Pronator syndrome and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2013, 21, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olewnik, Ł.; Podgórski, M.; Polguj, M.; Wysiadecki, G.; Topol, M. Anatomical variations of the pronator teres muscle in a Central European population and its clinical significance. Anat. Sci. Int. 2018, 93, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soubeyrand, M.; Melhem, R.; Protais, M.; Artuso, M.; Crézé, M. Anatomy of the median nerve and its clinical applications. Hand Surg. Rehabil. 2020, 39, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalska, B.; Sudoł-Szopińska, I. Ultrasound assessment on selected peripheral nerve pathologies. Part I: Entrapment neuropathies of the upper limb—Excluding carpal tunnel syndrome. J. Ultrason. 2012, 12, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asheghan, M.; Hollisaz, M.T.; Aghdam, A.S.; Khatibiaghda, A. The Prevalence of Pronator Teres among Patients with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Cross-sectional Study. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 12, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, H.C.; Park, J.K.; Kim, D.S.; Kang, S.W.; Kim, K.J.; Hong, S.H. Supracondylar process syndrome: Two cases of median nerve neuropathy due to compression by the ligament of Struthers. J. Pain. Res. 2018, 11, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, A. Pronator Syndrome Due to Schwannoma. J. Hand Microsurg. 2015, 7, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ruiter, G.C.W.; Wesstein, M.; Kurvers, A. Median Nerve Compression by the Ligament of Struthers: Clinical Image. World Neurosurg. 2025, 198, 124003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, V.S.; Dos Santos, T.R.; Duarte, M.L. Pronator Teres Syndrome—Case Report with Imaging Tests Diagnosis. Prague Med. Rep. 2025, 126, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgeman, C.; Naidu, S.; Kothari, M.J. Clinical and electrophysiological presentation of pronator syndrome. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2007, 47, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bair, M.R.; Gross, M.T.; Cooke, J.R.; Hill, C.H. Differential Diagnosis and Intervention of Proximal Median Nerve Entrapment: A Resident’s Case Problem. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Gupta, D.; Shrivastav, S. Lacertus Fibrosus Syndrome: A Case Report. Cureus 2023, 15, e47158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaram-Gilkes, M.; Fung, K.; Kiniale, C.; Adams, W. Bilateral Variations of Pronator Teres in the Upper Limb. Cureus 2024, 16, e66996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsaleem, S. Median nerve entrapment neuropathy: A review on the pronator syndrome. JSES Rev. Rep. Tech. 2024, 5, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balcerzak, A.A.; Ruzik, K.; Tubbs, R.S.; Konschake, M.; Podgórski, M.; Borowski, A.; Drobniewski, M.; Olewnik, Ł. How to Differentiate Pronator Syndrome from Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Comprehensive Clinical Comparison. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.O.; Rosén, I.; Thorngren, K.G. Clinical and Neurophysiologic Characteristics of the Pronator Syndrome. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1985, 197, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartz, C.R.; Linscheid, R.L.; Gramse, R.R.; Daube, J.R. The Pronator Teres Syndrome: Compressive Neuropathy of the Median Nerve. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1981, 63, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L.B.E.; Iyer, V.G.; Zhang, Y.P.; Shields, C.B. Proximal median nerve neuropathy: Electrodiagnostic and ultrasound findings in 62 patients. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1468813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.V.; Wu, W.T.; Hsu, P.C.; Yang, Y.C.; Özçakar, L. Ultrasonography in Pronator Teres Syndrome: Dynamic Examination and Guided Hydrodissection. Pain. Med. 2022, 23, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, G.; Gunsoy, Z.; Golgelioglu, F.; Bayrakcioglu, O.F.; Kizkapan, T.B.; Ozboluk, S.; Dinc, M.; Oguzkaya, S. The Role of Palmar Cutaneous Branch Release in Enhancing Surgical Outcomes for Severe Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafshak, T.S.; el-Hinawy, Y.M. The anterior interosseous nerve latency in the diagnosis of severe carpal tunnel syndrome with unobtainable median nerve distal conduction. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1995, 76, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Créteur, V.; Madani, A.; Sattari, A.; Bianchi, S. Sonography of the Pronator Teres: Normal and Pathologic Appearances. J. Ultrasound Med. 2017, 36, 2585–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurses, I.A.; Altinel, L.; Gayretli, O.; Akgul, T.; Uzun, I.; Dikici, F. Morphology and morphometry of the ulnar head of the pronator teres muscle in relation to median nerve compression at the proximal forearm. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2016, 102, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.W.; Shih, J.T.; Hung, S.T. Concurrent carpal tunnel syndrome and pronator syndrome: A retrospective study of 21 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017, 103, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, F.S.E.; Agarwal, A. A rare and severe case of pronator teres syndrome. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 2020, rjaa397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, I.; Hong, J.T.; Kim, M.S. Early surgical treatment of pronator teres syndrome. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2014, 55, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.J.; LaStayo, P.C. Pronator syndrome and other nerve compressions that mimic carpal tunnel syndrome. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2004, 34, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, H.; Zadra, A.; Popp, D.; Komjati, M.; Tiefenboeck, T.M. Outcome of Surgical Treated Isolated Pronator Teres Syndromes-A Retrospective Cohort Study and Complete Review of the Literature. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health. 2021, 19, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.T.; Weiss, M.D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Work-Related Proximal Median and Radial Nerve Entrapment. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 26, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strohl, A.B.; Zelouf, D.S. Ulnar Tunnel Syndrome, Radial Tunnel Syndrome, Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome, and Pronator Syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017, 25, e1–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogedano-Cruz, S.; González-de-la-Flor, Á.; Rodríguez-Anadón, C.; Bohn, L.; Villafañe, J.; Romero-Morales, C. Predicting median nerve depth from anthropometric features: A tool for safer invasive procedures. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0330383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaie, P.; Botchu, R.; Iyengar, K.; Drakonaki, E.; Sharma, G.K. Ultrasound-guided median nerve hydrodissection of pronator teres syndrome: A case report and a literature review. J. Ultrason. 2023, 23, e165–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donati, D.; Boccolari, P.; Tedeschi, R. Manual Therapy vs. Surgery: Which Is Best for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Relief? Life 2024, 14, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delzell, P.B.; Patel, M. Ultrasound-Guided Perineural Injection for Pronator Syndrome Caused by Median Nerve Entrapment. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 39, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. The forgotten DOMS: Recognising delayed muscle soreness in hand rehabilitation. Br. J. Sports Med. 2025, 59, 1120–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajkowski, S.; Pasek, J.; Cieślar, G. Foam Rolling or Percussive Massage for Muscle Recovery: Insights into Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS). J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, F.; Martins, W.; Behm, D.; Ribeiro, D.; Marinho, E.; Santos, W.; Viana, R.B. Acute effects of foam roller or stick massage on indirect markers from exercise-induced muscle damage in healthy individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2023, 35, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, I.S.; Dibai-Filho, A.V.; Dos Santos, P.G.; Júnior, J.D.A.; de Oliveira, D.D.; Rocha, D.S.; Fidelis-de-Paula-Gomes, C.A. Effects of foam roller on pain intensity in individuals with chronic and acute musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of randomized trials. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rałowska-Gmoch, W.; Hajzyk, M.; Matyskieła, T.; Łabuz-Roszak, B.; Dziadkowiak, E. The Diagnostic Pitfalls in the Pronator Teres Syndrome—A Case Report. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17100169

Rałowska-Gmoch W, Hajzyk M, Matyskieła T, Łabuz-Roszak B, Dziadkowiak E. The Diagnostic Pitfalls in the Pronator Teres Syndrome—A Case Report. Neurology International. 2025; 17(10):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17100169

Chicago/Turabian StyleRałowska-Gmoch, Wiktoria, Marcin Hajzyk, Tomasz Matyskieła, Beata Łabuz-Roszak, and Edyta Dziadkowiak. 2025. "The Diagnostic Pitfalls in the Pronator Teres Syndrome—A Case Report" Neurology International 17, no. 10: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17100169

APA StyleRałowska-Gmoch, W., Hajzyk, M., Matyskieła, T., Łabuz-Roszak, B., & Dziadkowiak, E. (2025). The Diagnostic Pitfalls in the Pronator Teres Syndrome—A Case Report. Neurology International, 17(10), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17100169