Sustainable Career Development for College Students: An Inquiry into SCCT-Based Career Decision-Making

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT)

2.2. Work Values and Career Decision-Making

2.3. The Mediating Effect of Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy

2.4. Moderating Effect of Career Goals

2.5. Background Variables

2.6. Research Model

3. Research Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale—Short Form (CDMSE-SF)

3.2.2. Career Value Scale

3.2.3. Career Goals Scale

3.2.4. Career Decision-Making Scale

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Normality Test

4.2. Convergent Validity

4.3. Discriminant Validity

4.4. Common Method Variance (CMV)

4.5. Difference Analysis

4.6. The Mediating Role of CDMSE and the Moderating Role of Career Goals

4.6.1. Model Fit Analysis

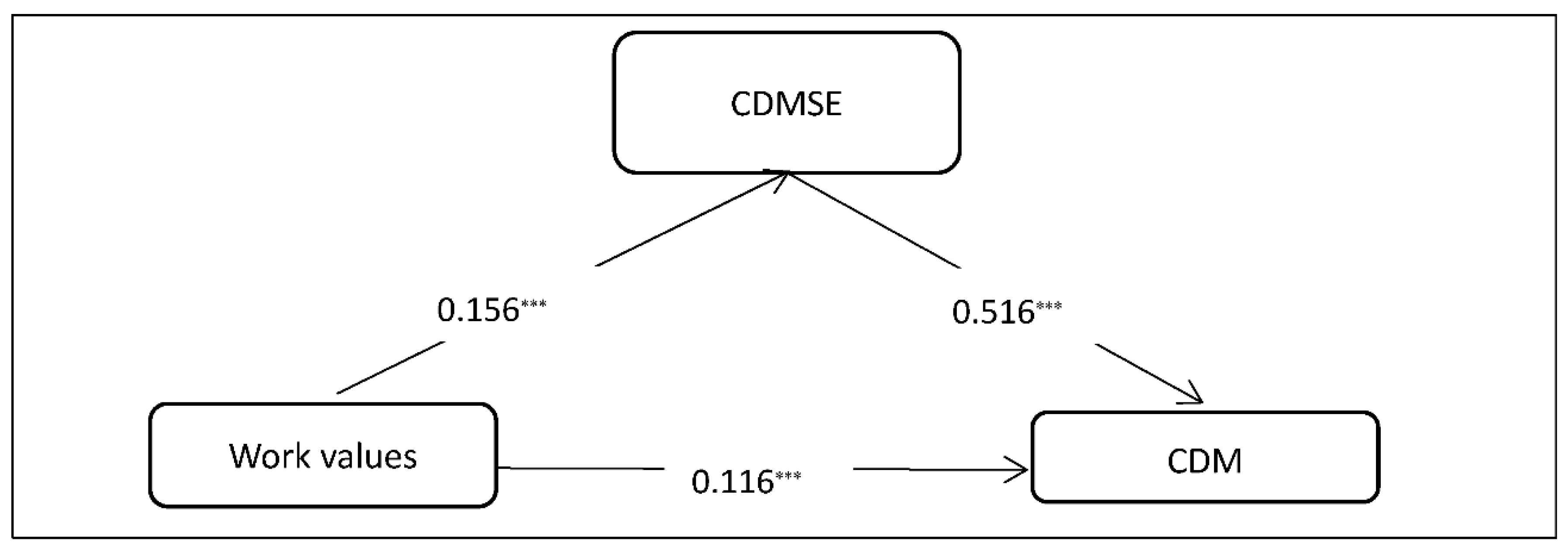

4.6.2. Direct and Indirect Effects

4.6.3. Moderating Role of Career Goals

5. Discussion

5.1. Differences in CDM across Background Variables

5.2. The Positive Effect of Work Values on CDM

5.3. The Mediating Role of CDMSE

5.4. Moderating Role of Career Goals

6. Contributions and Suggestions

6.1. Contributions

6.1.1. Theoretical Implications

6.1.2. Practical Implications

6.2. Suggestions

7. Research Limitations and Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Presti, A.L.; Capone, V.; Aversano, A.; Akkermans, J. Career competencies and career success: On the roles of employability activities and academic satisfaction during the school-to-work transition. J. Career Dev. 2022, 49, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Gu, X.; Chen, H.; Wen, Y. For the future sustainable career development of college students: Exploring the impact of core self-evaluation and career calling on career decision-making difficulty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabiyik, T.; Kao, D.; Magana, A.J. First-Year Exploratory Studiesabout Students’ Career Decision Processes and the Impact of Data-Driven Decision Making. Educ. Review. 2021, 5, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, M.; De Vos, A. When people don’t realize their career desires: Toward a theory of career inaction. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N.; Newman, A.; Jiang, Z.; Brouwer, M. Career optimism: A systematic review and agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 116, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.J.; Gu, M.; Hai, S. How can personality enhance sustainable career management? The mediation effects of future time perspective in career decisions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Heijden, B.I.; De Vos, A. Sustainable Careers: Introductory Chapter. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, M. The process of self-realization—From the humanist psychology perspective. Psychology 2019, 10, 1095–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trevor-Roberts, E.; Parker, P.; Sandberg, J. How uncertainty affects career behaviour: A narrative approach. Aust. J. Manag. 2019, 44, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiani, A.; Liu, J.; Ghani, U.; Popelnukha, A. Impact of future time perspective on entrepreneurial career intention for individual sustainable career development: The roles of learning orientation and entrepreneurial passion. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelks, S.M.; Crain, A.M. Sticking with STEM: Understanding STEM career persistence among STEM Bachelor’s Degree Holders. J. High. Educ. 2020, 91, 805–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M. A Study on the Strategies for lmproving the Employment Quality of College Students in China. Jiangsu Higher Educ. 2019, 10, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.H.; Tang, F.F.; Wu, K.M. Analysisof the Influencing Factors and Mechanism of Dynamic Changes of College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Educ. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 2021, 20, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemini-Gashi, L.; Duraku, Z.H.; Kelmendi, K. Associations betweensocial support, career self-efficacy, and career indecision among youth. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 4691–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L. The present situation analysis and cultivation countermeasure of the values of contemporary college students. Ideol. Theor. Educ. 2021, 12, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L. The Relationship between Occupational Values, Professional Commitment and Employability of College Students. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2021, 12, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Smith, I.; Pass, L.; Reynolds, S. How adolescents understand their values: A qualitative study. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Lindo, N.A. Acculturation moderating between international students’ career decision-making difficulties and career decision self-efficacy. Career Dev. Q. 2022, 70, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Wang, Y.X.; Dong, C.H. The Impact of College Students’ Professional Values on Employment Ability: The Mediating Role of Psychological Capital. China Univ. Stud. Career Guide 2022, 3, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorchangizi, B.; Borhani, F.; Abbaszadeh, A.; Mirzaee, M.; Farokhzadian, J. The importance of professional values from nursing students’ perspective. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, R.; Sahin, S. The effect of professional values of nurses on their attitudes towards caregiving roles. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2021, 27, e12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, H.A. Nurses’ professional values: Influences of experience and ethics education. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 2009–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.J.; Li, X.H.; Wei, K.; Hou, L.L.; Chen, X.; Xue, Y.Z. Relationship between professional values and ethical decision-making ability of higher vocational college nursing students. J. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 36, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Morris, T.R.; Penn, L.T.; Ireland, G.W. Social–cognitive predictors of career exploration and decision-making: Longitudinal testof the career self-management model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Ireland, G.W.; Penn, L.T.; Morris, T.R.; Sappington, R. Sources of self-efficacy and outcome expectations for career exploration and decision-making: A test of the social cognitive model of career self-management. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 99, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W. Career-life preparedness: Revisiting career planning and adjustment in the new workplace. Career Dev. Q. 2013, 61, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.; Lent, R.W. Social cognitive career theory at 25: Progress in studying the domain satisfaction and career self-management models. J. Career Assess. 2019, 27, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Koen, J. Contemporary career orientations and career self-management: A review and integration. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; do Céu Taveira, M.; Soares, J.; Marques, C.; Cardoso, B.; Oliveira, Í. Career decision-making in unemployed Portuguese adults: Test of the social cognitive model of career self-management. J. Couns. Psychol. 2022, 69, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremersch, J.; Van Hoye, G.; Van Hooft, E. How to successfully manage the school-to-work transition: Integrating job search quality in the social cognitive model of career self-management. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 131, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.; Galambos, N.L.; Krahn, H.J. Work values during the transition to adulthood and mid-life satisfaction. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2017, 41, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortheix, F.M.; Parker, P.D.; Lechner, C.M.; Schwartz, S.H. Changes in young Europeans’ values during the global financial crisis. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2019, 10, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daniel, E.; Benish-Weisman, M. Value development during adolescence: Dimensions of change and stability. J. Personal. 2019, 87, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox-Hayes, J.; Chandra, S.; Chun, J. The role of values in shaping sustainable development perspectives and outcomes: A case study of Iceland. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, C.; Nachmias, S.; McLaughlin, H.; Jackson, S. Personal values, social capital, and higher education student career decidedness: A new ‘protean’-informed model. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, J.J.; Shen, X.B. Aresearch on the influence of entrepreneur’s occupation values and resource bricolage on entrepreneurial performance. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 40, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauers, R.; Mahler, E. Factors that Contribute to Job Satisfaction of Millennials. Ph.D. Thesis, The College of St. Scholastica, Duluth, MN, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/d022b5fb6e1987a157cb40ef94907d0f (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Abessolo, M.; Rossier, J.; Hirschi, A. Basic values, career orientations, and career anchors: Empirical investigation of relationships. Front. Psychol. 2017, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramírez, I.; Fornells, A.; Del Cerro, S. Understanding undergraduates’ work values as a tool to reduce organizational turnover. Educ. Train. 2022, 64, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud, L.; Bernard, A.; Trinchera, L. Early career values and individual factors of objective career success: The case of the French business graduates. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 24, 350–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisha, C.; Anjali, M.; Sarita, S. A study on the Impact of Values on Career Decision Making of Adolescents. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2016, 4, 395–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sortheix, F.M.; Chow, A.; Salmela-Aro, K. Work values and the transition to work life: A longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ngo, H.Y.; Cheung, F. Linking protean career orientation and career decidedness: The mediating role of career decision self-efficacy. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.; Capezio, A.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Read, S.; Lajom, J.A.L.; Li, M. The role of traditionality in the relationships among parental support, career decision-making self-efficacy and career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 94, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Kim, D.Y. A cross cultural study of antecedents on career preparation behavior: Learning motivation, academic achievement, and career decision self-efficacy. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2013, 13, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, M.C.; Pallini, S.; Vecchio, G.M.; Nota, L.; Soresi, S. Future orientation and attitudes mediate career adaptability and decidedness. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P.; Patton, W.; Prideaux, L.A. Causal relationship between career indecision and career decision-making self-efficacy: A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. J. Career Dev. 2006, 33, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Penn, L.T.; Lent, R.W. The joint roles of career decision self-efficacy and personality traits in the prediction of career decidedness and decisional difficulty. J. Career Assess. 2019, 27, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, T.; Gati, I.; Guan, Y. Career decision-making profiles and career decision-making difficulties: A cross-cultural comparison among US, Israeli, and Chinese samples. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 88, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Argyropoulou, K.; Kaliris, A. From career decision-making to career decision-management: New trends and prospects for career counseling. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2018, 5, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germeijs, V.; Verschueren, K.; Soenens, B. Indecisiveness and high school students’ career decision-making process: Longitudinal associations and the mediational role of anxiety. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, C.F.; Tsai, H.H.; Kao, C.C. The construction of a career developmental counseling model for Taiwanese athletes. Phys. Educ. J. 2016, 49, 443–464. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.L.; Guan, J.F. Study on the Relationship between Occupational Values and Occupational Choice Self–Efficacy of Medical Graduates in a Medical University in Guangdong Province. Med. Soc. 2020, 33, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Pan, W.; Newmeyer, M. Factors influencing high school students’ career aspirations. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2008, 11, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Alessandri, G.; Eisenberg, N. Prosociality: The contribution of traits, values, and self-efficacy beliefs. J. Personal. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P. Prosocial agency: The contribution of values and self-efficacy beliefs to prosocial behavior across ages. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 26, 218–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, F. The Influence of the Work Values on College Students Employment. China Univ. Stud. Career Guide 2016, 12, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Lei, L. The Professional Values and Employability of College Students: The Mediating Role of Career Decision-Making Self Efficacy. Theory Pract. Educ. 2016, 36, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgstock, R. The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2009, 28, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.Y.; Kim, B.; Jang, S.H.; Jung, S.H.; Ahn, S.S.; Lee, S.M.; Gysbers, N. An individual’s work values in career development. J. Employ. Couns. 2013, 50, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Kraimer, M.L.; Holtom, B.C.; Pierotti, A.J. Even the best laid plans sometimes go askew: Career self-management processes, career shocks, and the decision to pursue graduate education. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colakoglu, S.; Caligiuri, P. Cultural influences on Mllennial MBA students’ career goals: Evidence from 23 countries. In Managing the New Workforce: International Perspective on the Millennial Generation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; pp. 262–280. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Callanan, G.A.; Godshalk, V.M. Career Management, 4th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-02967-000 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Latham, G.P. Goal-setting theory: Causal relationships, mediators, and moderators. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Psychol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.M.; Sun, Y.C. Bridging the Gap between Academic Goals and Career Goals by Compensatory Education: A Practical Exploration of Contemporary College Students’ Life Problems. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. 2021, 228, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.E.; Martin, D.F.; Carden, W.A.; Mainiero, L.A. The road less traveled: How to manage the recycling career stage. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2003, 10, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gushue, G.V.; Scanlan, K.R.; Pantzer, K.M.; Clarke, C.P. The relationship of career decision-making self-efficacy, vocational identity, and career exploration behavior in African American high school students. J. Career Dev. 2006, 33, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.B.; Ciani, K.D. Effects of anundergraduate career class on men’s and women’s career decision-making self-efficacy and vocational identity. J. Career Dev. 2008, 34, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, L.N. Research on the influencing factors and countermeasures of college students’ career decision-making. Educ. Explor. 2009, 299, 127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.Y. The influence of college students’self-efficacy and coping style on career decision-making. J. Minnan Norm. Univ. 2022, 35, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Investigation and Countermeasure Research of Career Decision-making Difficulties in Higher Vocational College Students. Guide Sci. Educ. 2021, 22, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.H.; Huang, J.T. The effects of socioeconomic status and proactive personality on career decision self-efficacy. Career Dev. Q. 2014, 62, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, M.D.; Krleza-Jeric, K.; Lemmens, T. The declaration of Helsinki. BMJ 2007, 335, 624–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, N.E.; Klein, K.L.; Taylor, K.M. Evaluation of a short form of the career decision-making self-efficacy scale. J. Career Assess. 1996, 4, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.Y. Research on Work Values-Job Supplies Fit of New Generation Construction Project Management Professionals. Ph.D. Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2020. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFDLAST2022&filename=1021809294.nh (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Yu, Y.H. Research on Integrated Model of Career Decision-Making. Ph.D. Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2004. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFD9908&filename=2004087152.nh (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Xu, H. Development and initial validation of the constructivist beliefs in the career decision-making scale. J. Career Assess. 2020, 28, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.H.; Lee, Y.S.; He, Z. The Relationship Among Expectancy Belief, Course Satisfaction, Learning Effectiveness, and Continuance Intention in Online Courses of Vocational-Technical Teachers College Students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 904319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.G.; Olsson, U.H. Specification Search in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): How Gradient Component-wise Boosting can Contribute. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2022, 29, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phakiti, A. Confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling. In The Palgrave Handbook of Applied Linguistics Research Methodology; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 459–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W. Asymptotically distribution-free methods for the analysis of covariance structures. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1984, 37, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, K.V.; Foster, K. Omnibus tests of multinormality based on skewness and kurtosis. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1983, 12, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 1989, 17, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Market. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hox, J.J.; Bechger, T.M. An introduction to structural equation modeling. Fam. Sci. Rev. 1998, 11, 354–373. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Lau, R.S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 296–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Wang, Z.H. Thesis Statistical Analysis Practice: SPSS and AMOS Applications, 4th ed.; Wunan Book Publishing Company: Taipei, Taiwan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abedi, G.; Rostami, F.; Nadi, A. Analyzing the dimensions of the quality of life in hepatitis B patientsusing confirmatory factor analysis. Glob. J. Cf Health Acience 2015, 7, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kazi, A.S.; Akhlaq, A. Factors affecting students’ career choice. J. Res. Reflect. Educ. 2017, 11, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, F.H. Analysis and countermeasures of female college students’ career choice dilemma. High. Educ. Forum 2017, 8, 120–122. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.H. A Study on the Information Processing of Anxiety Individuals in Mult-i attribute Decision-making Tasks. J. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 29, 1157–1158+1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.P.; Xie, B.G. The Level, Demographic Characteristics and Biographical Antecedents of Career Decision-Making Difficulties in College Students: An Exploring Study. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 2017, 5, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, C.A.; Hoogendoorn, B. The mediating role of values in the relationship between religion and entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 1309–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.H. Values Education for Chinese and Foreign College Students: Empirical Investigation and Comparison. Educ. Res. 2022, 43, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.H. The analysis of contemporary college students’ social mentality from the perspective of values and the exploration of guiding path. Stud. Core Soc. Values 2022, 8, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, F.; Rao, Z.; Yang, Y. The effect of proactive personality on college students’ career decision-making difficulties: Moderating and mediating effects. J. Adult Dev. 2021, 28, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, S.R.A.; Kai Le, K.; Musa, S.N.S. The mediating role of career decision self-efficacy on the relationship of career emotional intelligence and self-esteem with career adaptability among university students. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2021, 26, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gati, I.; Kulcsár, V. Making better career decisions: From challengesto opportunities. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, M.; Feldmann, M.; Vegetti, F. Work values and the value of work: Different implications for young adults’ self-employment in Europe. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2019, 682, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z. Career decision-making self-efficacy mediates the effect of social support on career adaptability: A longitudinal study. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroevers, M.; Kraaij, V.; Garnefski, N. How do cancer patients manage unattainable personal goals and regulate their emotions. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wrosch, C.; Miller, G.E.; Scheier, M.F.; De Pontet, S.B. Giving up on unattainable goals: Benefits for health? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llenares, I.I.; Deocaris, C.C.; Deocaris, C.C. Work values of Filipino college students. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2021, 49, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praskova, A.; Creed, P.A.; Hood, M. Facilitating engagement in new career goals: The moderating effects of personal resources and career actions. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2013, 13, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, N.W. Optimize college students’ career development education based on the improvement of employment quality. Ideol. Theor. Educ. 2022, 7, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, K. Career decision-making for agriculture student’s sustainability. Agric. Educ. Mag. 2008, 80, 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, S.; Lichtenstein, G.; Higgs, M. Personal values at work: A mixedmethods study of executives’ strategic decision-making. J. Gen. Manag. 2017, 43, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Quantity | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 329 | 27% |

| Female | 874 | 73% | |

| Grade | (Low) Freshman and sophomore year | 545 | 72% |

| (High) Junior and senior years | 249 | 28% | |

| Household income (RMB) | Below 5000 (including 5000) | 644 | 54% |

| More than 5000 | 559 | 46% | |

| Educational level | Junior college | 480 | 40% |

| Undergraduate course | 723 | 60% | |

| M | SD | Number of Questions | Mardia Coefficient | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | - | - | - | - | >0.70 |

| Career Goals | 2.970 | 0.766 | 5 | 19.821 | 0.907 |

| Career Value | 3.744 | 0.398 | 21 | 248.950 | 0.886 |

| CDM | 3.389 | 0.640 | 9 | 61.356 | 0.855 |

| CDMSE | 3.458 | 0.645 | 24 | 348.047 | 0.964 |

| SFL | t | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | >0.50 | >1.96 | >0.60 | >0.50 |

| Career Goals | 0.743–0.853 | 29.059–37.161 | 0.907 | 0.662 |

| Career Value | 0.557–0.904 | 20.598–39.989 | 0.760–0.913 | 0.517–0.640 |

| CDM | 0.660–0.813 | 21.842–31.149 | 0.763–0.873 | 0.520–0.536 |

| CDMSE | 0.713–0.852 | 29.570–36.156 | 0.864–0.915 | 0.632–0.684 |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.813 | ||||||||||||

| B | 0.313 ** | 0.8 | |||||||||||

| C | 0.094 ** | 0.127 ** | 0.766 | ||||||||||

| D | 0.081 ** | 0.112 ** | 0.398 ** | 0.78 | |||||||||

| E | 0.092 ** | 0.123 ** | 0.433 ** | 0.368 ** | 0.791 | ||||||||

| F | 0.089 ** | 0.171 ** | 0.295 ** | 0.246 ** | 0.292 ** | 0.719 | |||||||

| G | 0.082 ** | 0.014 | −0.026 | 0.033 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.72 | ||||||

| H | 0.233 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.108 ** | 0.093 ** | 0.061 ** | 0.126 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.732 | |||||

| I | 0.512 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.056 | 0.048 | 0.033 | 0.077 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.483 ** | 0.795 | ||||

| J | 0.474 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.078 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.443 ** | 0.780 ** | 0.827 | |||

| K | 0.485 ** | 0.328 ** | 0.028 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.081 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.787 ** | 0.802 ** | 0.805 | ||

| L | 0.448 ** | 0.372 ** | 0.125 ** | 0.114 ** | 0.095 ** | 0.144 ** | 0.148 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.699 ** | 0.639 ** | 0.721 ** | 0.825 | |

| M | 0.452 ** | 0.425 ** | 0.099 ** | 0.072 * | 0.085 ** | 0.130 ** | 0.209 ** | 0.473 ** | 0.723 ** | 0.679 ** | 0.738 ** | 0.797 ** | 0.807 |

| Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval Bias-Corrected Percentile Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bounds | Upper Bounds | ||

| Career Value → CDMSE → CDM | 0.081 | 0.045 | 0.120 |

| Career Value → CDM | 0.116 | 0.056 | 0.175 |

| Career Value → CDMSE | 0.156 | 0.086 | 0.232 |

| CDMSE → CDM | 0.516 | 0.056 | 0.175 |

| Career Value → CDM (Total) | 0.197 | 0.124 | 0.271 |

| Threshold | Low-Grouped Sample Verification Values | High-Grouped Sample Verification Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFI | >0.800 | 0.902 | 0.892 |

| AGFI | >0.800 | 0.849 | 0.836 |

| RMR | >0.080 | 0.031 | 0.051 |

| NFI | >0.800 | 0.881 | 0.875 |

| NNFI | >0.800 | 0.870 | 0.851 |

| CFI | >0.800 | 0.900 | 0.885 |

| RFI | >0.800 | 0.846 | 0.838 |

| IFI | >0.800 | 0.900 | 0.885 |

| PNFI | >0.500 | 0.681 | 0.676 |

| PGFI | >0.500 | 0.589 | 0.584 |

| Model | χ2 | DF | Δχ2 | ΔDF | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | baseline model | 808.894 | 102 | 8.854 | 1 | 0.003 ** |

| Model 2 | interference model | 817.748 | 103 | |||

| Path | High Grouping of Career Goals | Low Grouping of Career Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Estimates | ||

| CDMSE → CDM | 0.551 *** | 0.362 ** |

| Hypothesis | Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Work values have a significant positive impact on college students’ CDM. | assumption holds |

| H2 | CDMSE plays a mediating role in professional values and CDM. | |

| H3 | Career goals play a moderating role in CDMSE and CDM. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.-H.; Wang, H.-P.; Lai, W.-Y. Sustainable Career Development for College Students: An Inquiry into SCCT-Based Career Decision-Making. Sustainability 2023, 15, 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010426

Wang X-H, Wang H-P, Lai W-Y. Sustainable Career Development for College Students: An Inquiry into SCCT-Based Career Decision-Making. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010426

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xin-Hai, Hsuan-Po Wang, and Wen-Ya Lai. 2023. "Sustainable Career Development for College Students: An Inquiry into SCCT-Based Career Decision-Making" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010426