Participatory Design to Enhance ICT Learning and Community Attachment: A Case Study in Rural Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Digital Divide in Taiwan

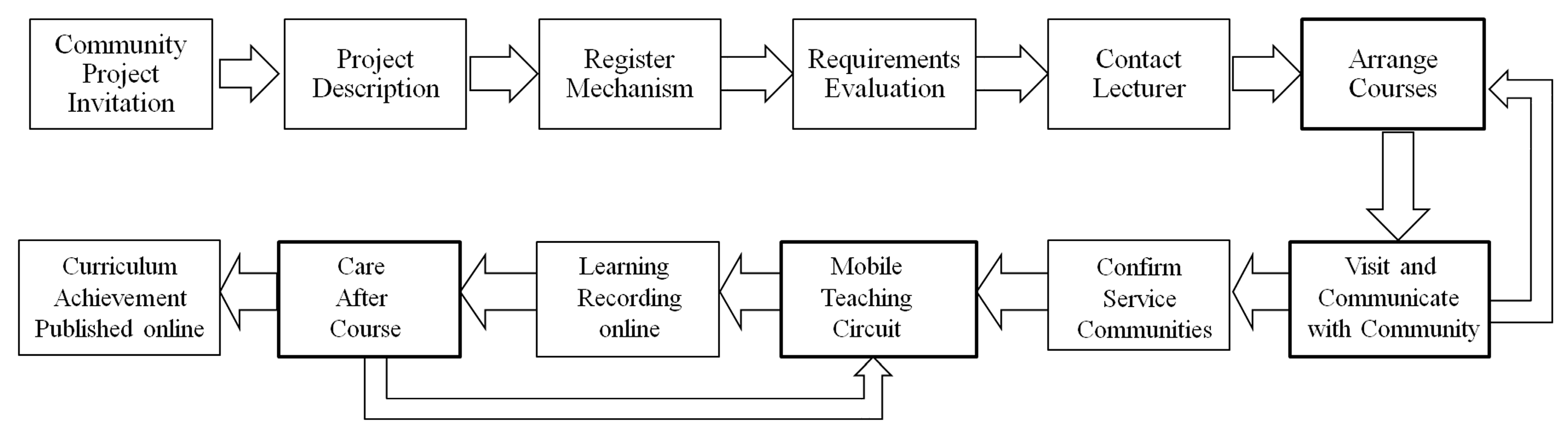

1.2. Background of PunCar Action

| Implementation unit | ADCT, Association of digital culture Taiwan (NPO) |

|---|---|

| Starting date | May 17, 2008 |

| Total lectures | 628 |

| Total teaching hours | 2884 h |

| Average number of students per lecture | 15 |

| Number of volunteer lecturers | 88 |

| Average number of lectures at each community | 6.5 |

| Total number of students | 12,056 |

| Average age of students | 53.2 years old |

| PunCar Action Van | Replaced four vans |

| Total mileage | 316,000 Km |

2. Methods

| Group | Interviewees | Content | Notation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PunCar students | Mr. SA | Their opinions about computers and the internet before taking the courses/the greatest reward obtained from the courses/their favorite content/ their follow-up ideas on how to use the Internet | Age 68, farmer |

| Ms. SB | Age 60, housewife | ||

| Mr. SC | Age 70, retired farmer | ||

| Ms. SD | Age 29, immigrant bride | ||

| PunCar executives | Cheng-Li Hsu | Their observations and thoughts of digital divide in rural communities/how to communicate with communities to learn their requirements/teaching experiences/programming experience of teaching materials and methods | Age 32, PunCar lecturer |

| Che-Ming Wu | Age 28, the director of PunCar | ||

| Ting-Yao Hsu | Age 33, the founder of PunCar | ||

| Community members | Ms. CA | Their expectations towards the PunCar curriculum/their opinions on the ICT curriculum in terms of community development combined with operational experience | Church pastor |

| Mr. CB | Community Leader |

2.1. Participatory Design Methods in ICT Learning

2.2. Research Framework

| Stakeholders | Focus on collaborative activities |

|---|---|

| PunCar executives | Communicating with communities and learning their actual ICT application requirements; analyzing tour experience |

| PunCar lecturers | Planning and designing the curriculum; giving lectures; adjusting the teaching material and method |

| PunCar volunteers | Helping students to operate the ICT tools one on one; setting up class equipment |

| Community members | Offering an introduction to community features; outlining the goal of promoting a digitalized community |

| PunCar students (ICT curriculum) | Voicing their ICT application requirements and learning the skills; Co-creating community blogs |

| Social workers in local government | Injecting resources from the local government, such as hardware and community development funds |

3. Case Study Results

3.1. Identifying ICT Needs of Rural Community

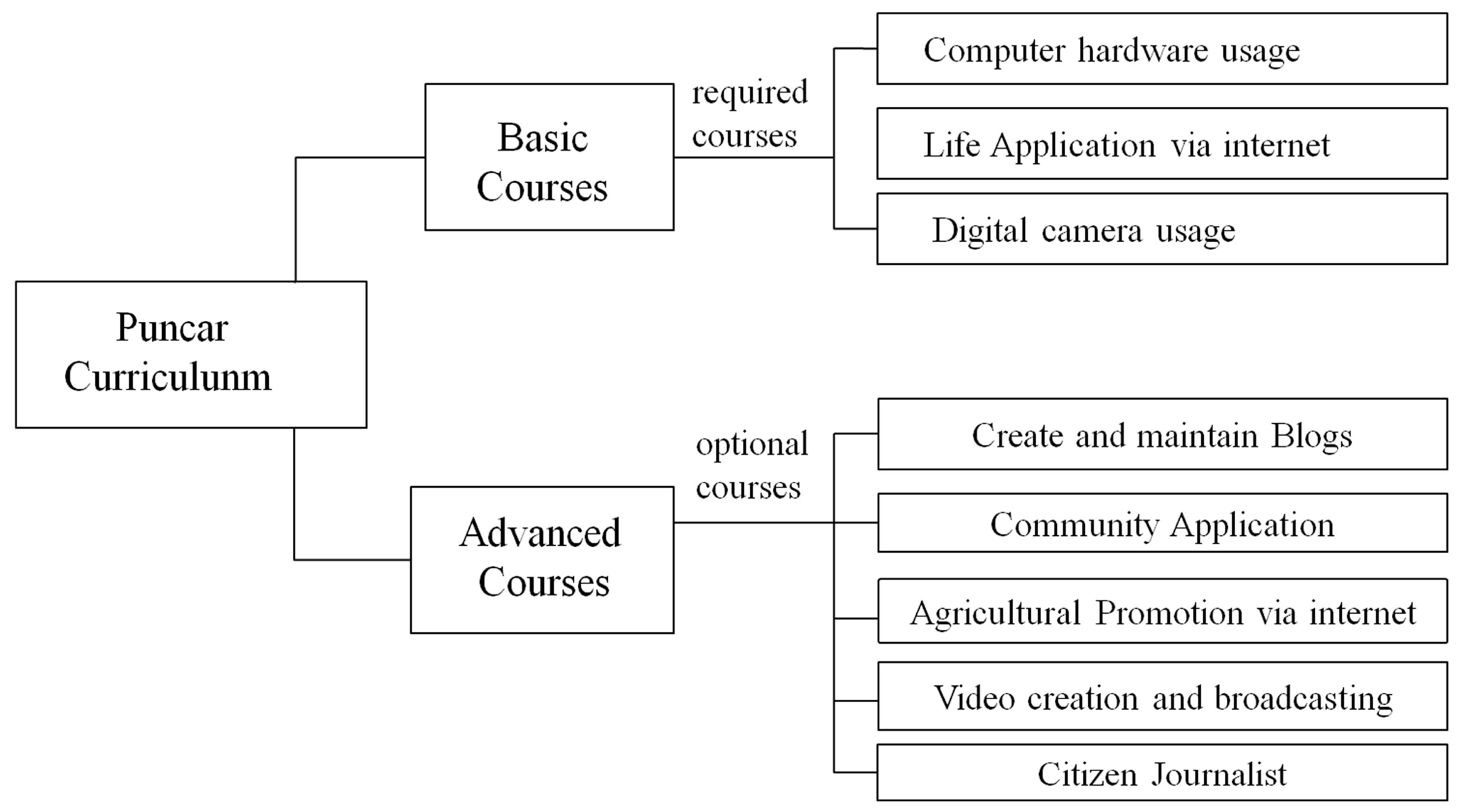

3.2. Learning ICT and Web 2.0 Skills

3.3. Co-Creating Community Blogs

| Reviving the core functions of communities |

| Through its interaction with the communities and understanding of local customs and practices, PunCar Action engaged in communication with those residents who had a positive learning attitude, and helped them to build and use the community blogs as the core of the curriculum. In addition, student learning conditions were evaluated. If the conditions were desirable, they would arrange more courses such as using internet communication tools, camera techniques, simple photo editing and management, and online digital map applications. Internet tools link all the service points together, which help to revive current community services and functions. |

| Local characteristic industry marketing |

| Although the core curriculum was also designed to teach residents how to build and use community blogs, PunCar Action helped communities with local characteristics and local industries to enhance their ability to develop more integrated internet applications. The main courses included camera techniques, simple photo editing and management, online digital map applications, audio-visual media applications and internet marketing practices. For each community, it benefitted network management and operations. |

3.4. Sustaining Intrinsic Motivation

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of PunCar Action’s Features

- (1)

- Bringing “economical” equipment into courses: The internet environment is set up using computer equipment from community centers, churches or temples, together with laptops, digital cameras and network equipment provided by PunCar. Freeware applications (Google map, Blogger, Picasa, YouTube) are used as the main teaching platform.

- (2)

- “Friendly” teaching of ICT tools applications: In a technological society, a sense of uncertainty among most senior citizens means that they forgo opportunities to engage in ideas and activities in which the younger generation participates [29]. Intergenerational education is adopted to eliminate digital divide between urban and rural areas, adjusting the roles of “teachers” and “students”. The primary goal is to remove senior citizen’s fear of computers and the internet. Thus, courses are taught in local dialects, students gain experience using computers, instructions are given at a slower pace, and the themes are related to the community. This friendly teaching environment allows rural residents to gain a sense of familiarity and achievement through the use of ICT tools (both hardware and software).

- (3)

- Tour courses in nearby areas: To determine whether intergenerational learning is successful, what should be noted is not only whether the activities are designed to meet the objectives of the program, but also the participants’ interests and abilities, as well as the assessment of actual conditions [30]. In this case study, whether the classroom is near enough to their home is crucial to a senior citizens’ enthusiasm for learning. Daily activities of residents in rural communities are mainly at community centers, and PunCar students form a learning group with a degree of homogeneity (i.e., age, lifestyle patterns, interests). For these reasons, the mobile classroom of PunCar selects places near the homes of participants for the convenience of community residents. This reduces their fear of ICT by creating a relaxed environment, and increases the community learning groups’ passion for learning how to use ICT.

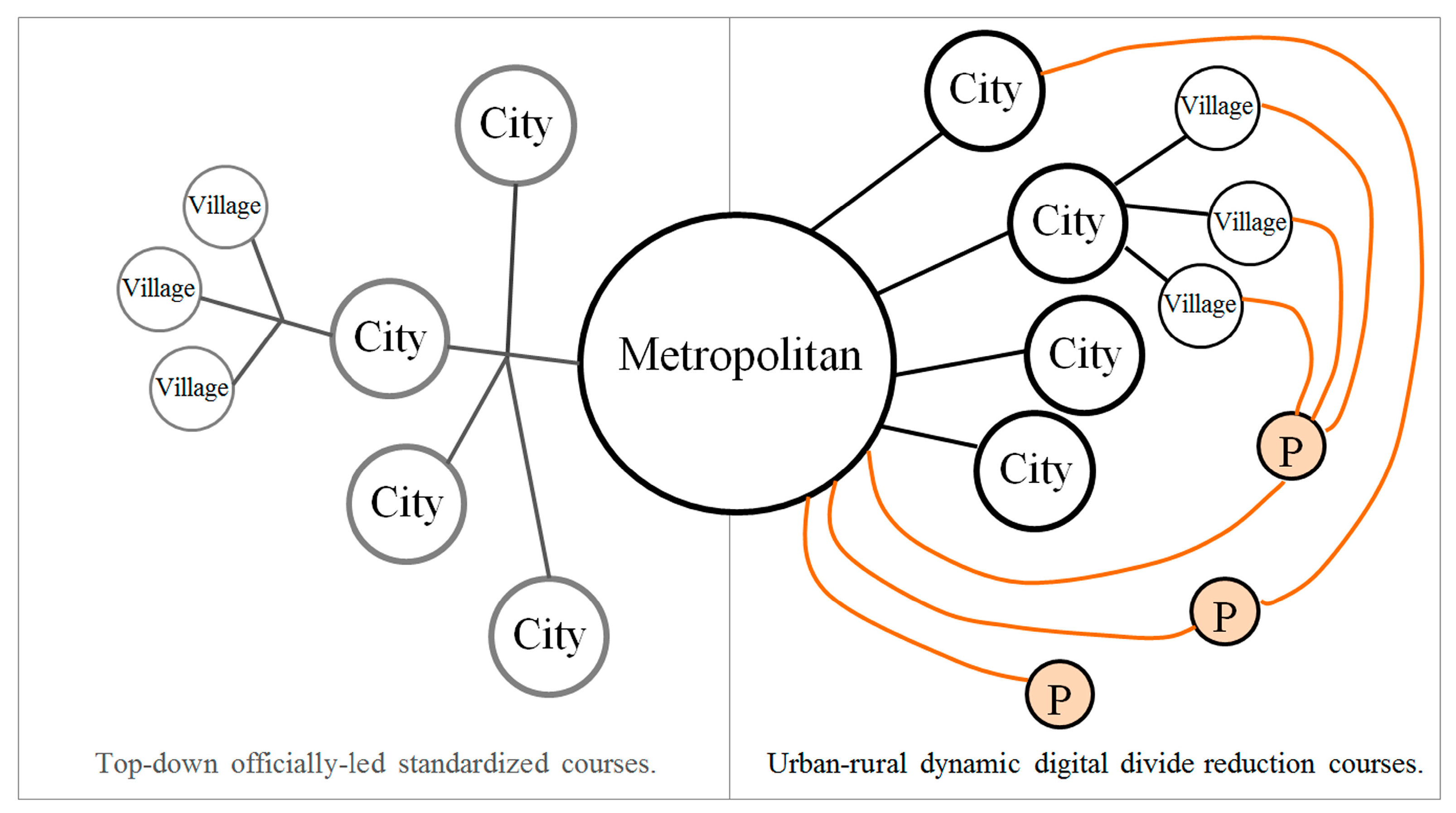

4.2. How Participatory Design Affects ICT Learning in Rural Communities

- (1)

- Teaching and learning in participatory design: Participatory design emphasizes both individual differences and participation in groups [21], such that community residents gain the opportunity to engage in the planning and execution process for community development through learning and technical assistance [19]. In the case study of PunCar, it is evident that the bottom-up form of participatory design [32] significantly influences “learning the ICT needs in communities” for ICT teaching in rural communities.

- (2)

- Participatory design in rural community digitization: The idea of participatory design in community informatics was prevalent in North America in the 1990s. It mainly concerned websites and information systems co-created by the joint participation of community residents, nonprofit organizations, professional information systems staff, and community co-management sections [32]. One of the crucial ideas is the concept of human-centered computing. In Carroll and Rosson’s [32] 13-year case study of the Civic Nexus community in Pennsylvania, U.S., through the participatory design of community stakeholders, the community achieved a consensus and division of labor to complete the following work step by step: identifying a need for IT, organizing for an IT Change, learning a new IT Skill, and creating and sustaining intrinsic motivation. The most important accomplishment was establishing community informatics based on the needs of users.

4.3. Distinctive ICT Courses Suitable for the Rural Elderly and the Revival of Communities

- (1)

- Dynamic teaching methods to enhance one’s confidence in dealing with ICT: In rural communities, the education of students extends mainly to junior high school, and the most common occupations are farmers, housewives, and immigrant brides. Therefore, teaching methods must be suitably adjusted according to the individual differences of students. In this study, the teacher-student ratio of PunCar Action was an average of one lecturer and approximately two to three volunteers to 15 students. During class, students operated the ICT tools themselves and provided feedback as a means of verifying that they were familiar with the use of ICT tools (including hardware and software).

- (2)

- Ames and Youatt [30] stipulated that the most appropriate intergenerational course planning must meet four standards: meet the objectives of courses or activities; determine the appropriateness of activities; consider the interests and abilities of participants; and assess actual conditions. Through participant observation in this case study, we found that senior citizens in rural communities have a lot of time but are not often accompanied by others. Thus, learning how to operate the computers and type quickly are not necessarily the digital skills they need most. Digital skills are a tool and a means. The purpose is to allow rural residents to go online to make a doctor’s appointment, purchase a train ticket, talk with children working in other cities via video conferencing, use digital cameras to take photos and then upload the photos to share with family and friends. Therefore, basic courses focus on teaching the residents of rural communities how to make life more convenient through the use of computers and the internet, because they are such effective tools for connecting with family and friends.

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foreseeing Innovative New Digiservices (FIND). 2010 Survey of Current State and Level of Demand on Household Broadband in Taiwan; Institute for Information Industry: Taipei, Taiwan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). World Information Society Report. 2007. Available online: http://www.itu.int/net/home/index.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2014).

- Tseng, S.F. Integration Policy Research of Networking Society Development; Research, Development and Evaluation Commission (RDEC): Taipei, Taiwan, 2007.

- Sanchez, J.; Salinas, A.; Harris, J. Education with ICT in South Korea and Chile. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2011, 31, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne, K. Digital Divides: Youth, Equity, and Information Technology. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.J.; Adams, A.E. Do rural residents really use the internet to build social capital? An empirical investigation. Am. Behav. Sci. 2010, 53, 1389–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.C.; Robert, L.; Charles, S.; Alcides, V. The use of online social networking by rural youth and its effects on community attachment. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2011, 14, 726–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. Reconsidering political and popular understandings of the digital divide. New Media Soc. 2004, 6, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, R. Learning about Information Technologies and Social Change: The Contribution of Social Informatics. Inf. Soc. 2000, 16, 271–232. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P. Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, G. Bridging urban digital divides? Urban polarization and information and communication technologies (ICTs). Urban. Stud. 2002, 39, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, E.B. Closing the digital divide in rural America. Telecommun. Policy 2000, 24, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research, Development and Evaluation Commission (RDEC). Executive Yuan 2010 Individual/Household Digital Divide Survey; Research, Development and Evaluation Commission (RDEC): Taipei, Taiwan, 2010.

- National Immigration Agency Global Web Site. Available online: http://www.immigration.gov.tw/mp.asp?mp=2 (accessed on 20 November 2014).

- E-Taiwan Program. Official Website Information. Available online: http://www.etaiwan.nat.gov.tw/ (accessed on 1 July 2014).

- PunCar Official Website Information. Available online: http://puncar.tw (accessed on 10 July 2014).

- The ARS Electronica Information. Available online: http://new.aec.at/news/en (accessed on 2 July 2014).

- Huang, C.H.; Huang, Y.T. A New Approach to Achieve e-Inclusion with ICT Education in Rural Taiwan. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2011, 210, 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- Sanoff, H. Origins of community design. Progress. Plan. 2006, 166, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Seale, J. Doing student voice work in higher education: An exploration of the value of participatory methods. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 36, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanoff, H. Special issue on participatory design. Des. Stud. 2007, 28, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodker, S.; Greenbaum, J.; Kyng, M. Setting the Stage for Design as Action. In Design at Work: Cooperative Design of Computer Systems; Greenbaum, J., Kyng, M., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Large, A.; Nesset, V.; Beheshti, J.; Bowler, L. Bonded design: A novel approach to intergenerational information technology design. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2006, 28, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druin, A. The role of children in the design of new technology. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2002, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaigeorgiou, G.; Triantafyllakos, G.; Tsinakos, A. What if undergraduate students designed their own web learning environment? Exploring students’ web 2.0 mentality through participatory design. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2011, 27, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tianpu Community Blog. Available online: http://tp5749731.blogspot.com/ (accessed on 30 June 2014).

- Shanhua Community News on PeoPo Citizen Online News Platform. Available online: http://www.peopo.org/soso6726 (accessed on 28 June 2014).

- Tianpu Community Fans Page on Facebook. Available online: http://www.facebook.com/tp5749731 (accessed on 30 June 2014).

- Storm, R.D.; Storm, S.K. Intergenerational learning and family harmony. Educ. Gerontol. 2000, 26, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, B.D.; Youatt, J.P. Intergenerational education and service programming: A model for selection and evaluation of activities. Educ. Gerontol. 1994, 20, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS)—eLAC 2007: Shaw, R. In Access and Digital Inclusion. In Proceedings of the WSIS Meeting, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7 June 2005.

- Carroll, J.M.; Rosson, M.B. Participatory design in community Informatics. Des. Stud. 2007, 28, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.; Valcke, M.; Braak, J.; Tondeur, J. Student teachers thinking processes and ICT integration: Predictors of prospective teaching behaviors with educational technology. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, A.; Sanchez, J. Digital inclusion in Chile: Internet in rural schools. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2009, 29, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, B.; Bianca, C.R. The participatory web: A user perspective on Web 2.0. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toker, Z. Recent trends in community design: The eminence of participation. Des. Stud. 2007, 28, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.-T. Participatory Design to Enhance ICT Learning and Community Attachment: A Case Study in Rural Taiwan. Future Internet 2015, 7, 50-66. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi7010050

Huang Y-T. Participatory Design to Enhance ICT Learning and Community Attachment: A Case Study in Rural Taiwan. Future Internet. 2015; 7(1):50-66. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi7010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yi-Ting. 2015. "Participatory Design to Enhance ICT Learning and Community Attachment: A Case Study in Rural Taiwan" Future Internet 7, no. 1: 50-66. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi7010050

APA StyleHuang, Y.-T. (2015). Participatory Design to Enhance ICT Learning and Community Attachment: A Case Study in Rural Taiwan. Future Internet, 7(1), 50-66. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi7010050