From IoT to AIoT: Evolving Agricultural Systems Through Intelligent Connectivity in Low-Income Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Questions

1.2. Research Objectives

- Examine the evolution of IoT toward AIoT in agriculture and its transformative impact.

- Identify and analyze key applications, enabling technologies, and challenges shaping this transition.

- Propose a flexible AIoT-based architecture adapted to the realities of low- and middle-income countries.

- Evaluate strategies to overcome persistent constraints, including infrastructural limitations, resource scarcity, and ethical concerns.

- Highlight pathways for building sustainable, resilient, and inclusive agricultural systems through intelligent connectivity.

1.3. Major Contributions of the Study

- Constraint-aware synthesis for low-income contexts: Unlike existing IoT–AIoT surveys that primarily emphasize technological performance and application benchmarking in high-resource settings, this review provides a systematic synthesis focused on low-income countries, with particular emphasis on African agricultural systems. It explicitly analyzes infrastructural, socio-economic, and digital capacity constraints that shape AIoT adoption, while highlighting opportunities for frugal innovation, participatory data generation, and leapfrogging deployment models.

- Structured analytical framework across AI pillars: The study introduces a conceptual framework centered on three interdependent AI pillars, Data, Features, and Models. By jointly examining challenges and opportunities across these dimensions, the review explains why conventional AIoT approaches often fail in resource-constrained environments and how context-adapted solutions can be designed.

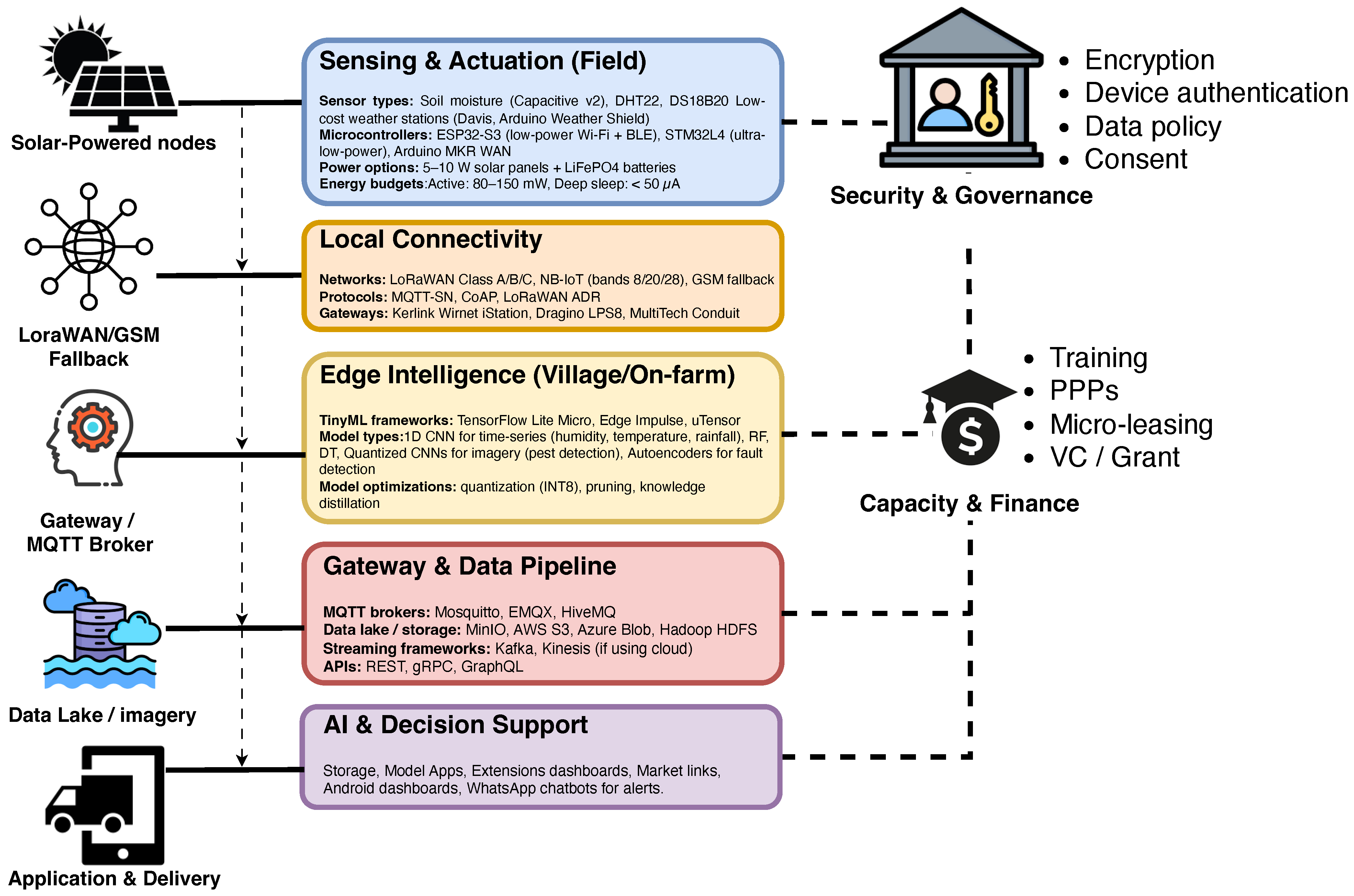

- Context-adapted AIoT reference architecture: This work proposes a lightweight and modular AIoT reference architecture tailored to low-income agricultural contexts. The architecture integrates low-power sensing, long-range connectivity, edge intelligence (TinyML), and embedded governance mechanisms to address affordability, energy efficiency, intermittent connectivity, and data sovereignty.

- Integrated technical and governance perspective: Beyond technical considerations, the review explicitly incorporates governance, ethical, and sustainability dimensions, including data ownership, algorithmic transparency, and inclusive access. This integrated perspective responds to the limitations of technology-centric surveys and reflects the realities of AIoT deployment in vulnerable agricultural systems.

- Actionable insights for inclusive and sustainable agriculture: By bridging technological design, contextual constraints, and policy-relevant considerations, this study provides actionable guidance for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners seeking to develop resilient, equitable, and sustainable AIoT-enabled agricultural systems in the Global South.

1.4. Paper Organization

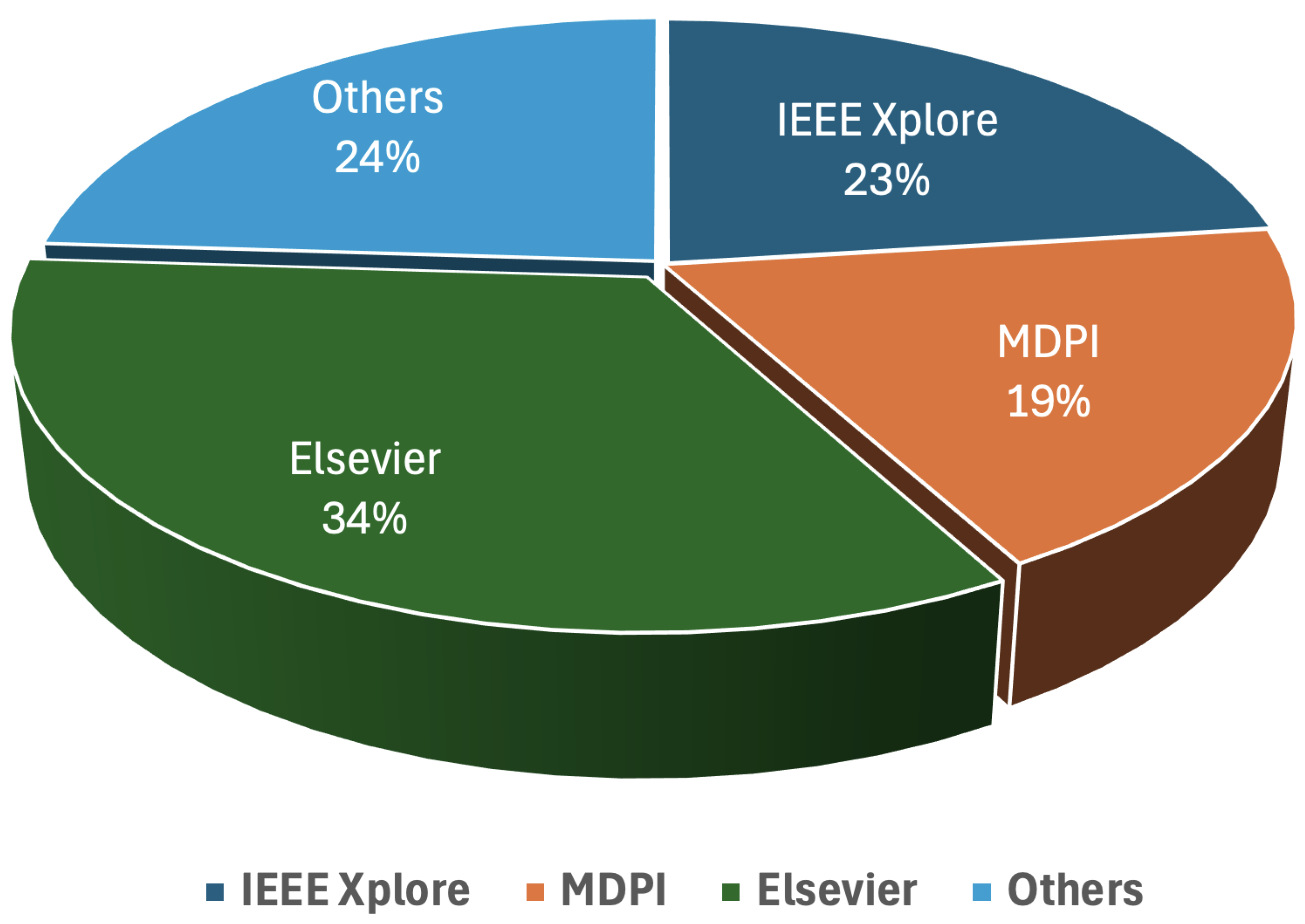

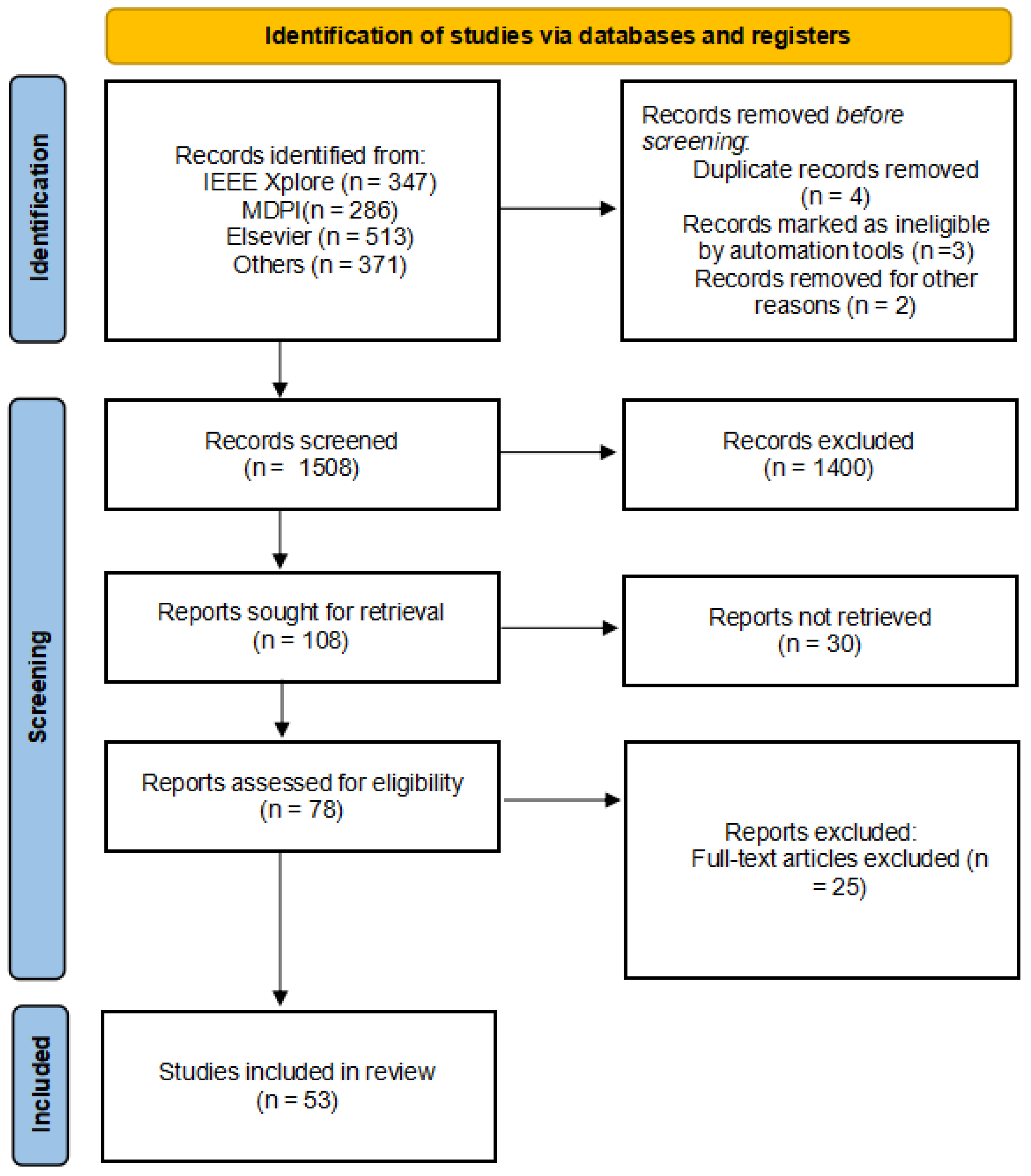

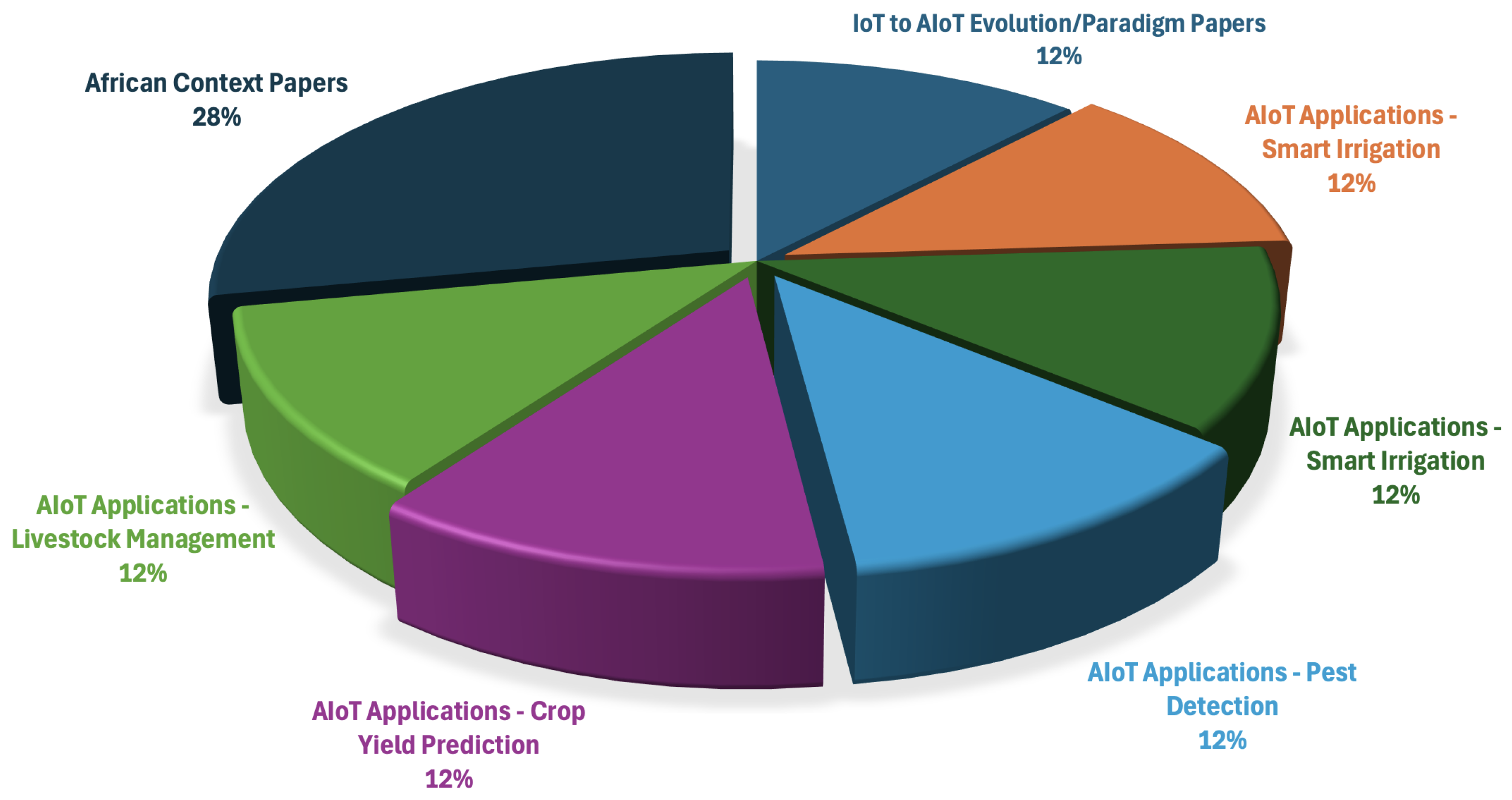

2. Research Methodology

3. Technological Evolution of Smart Farming Systems

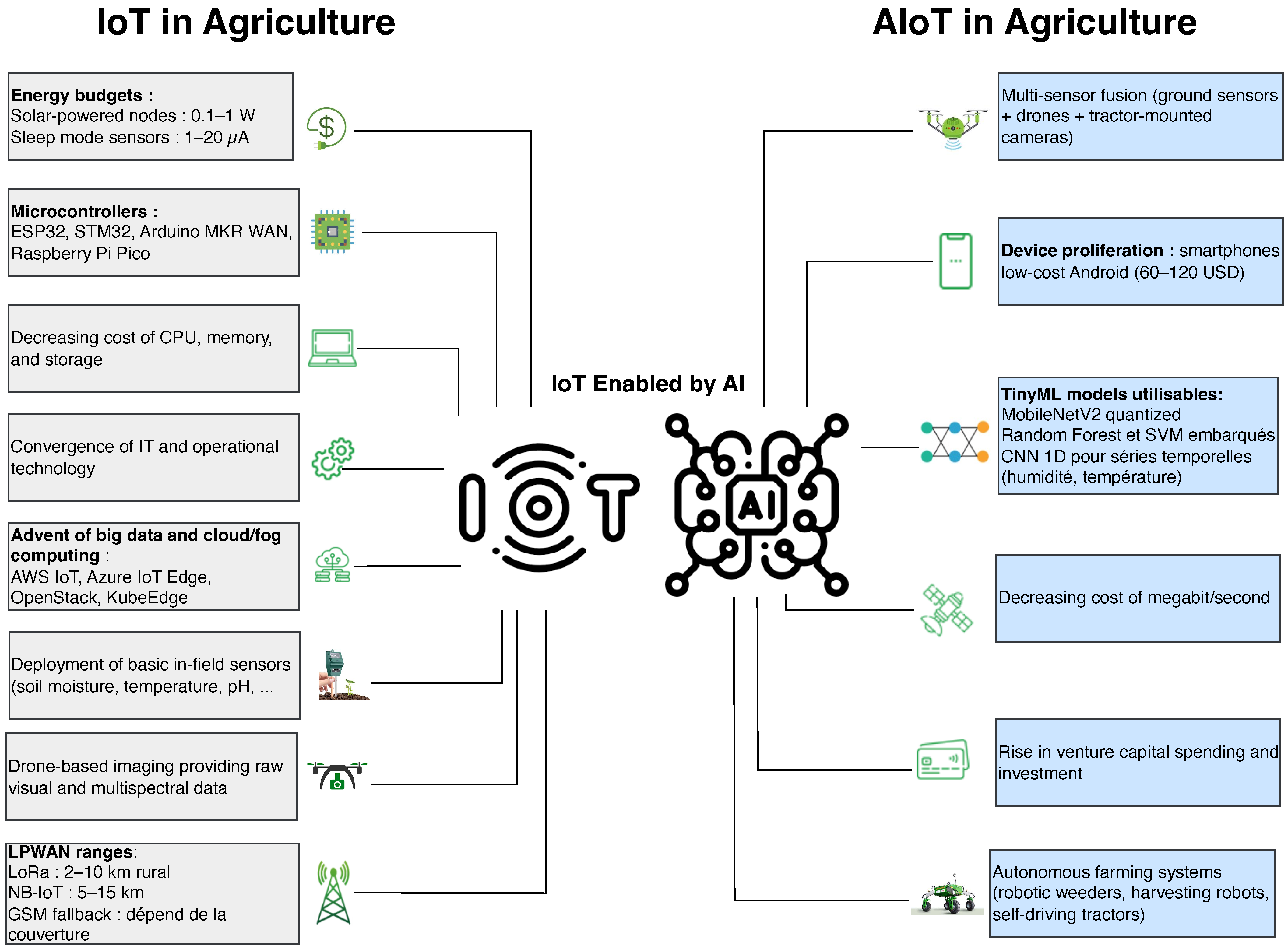

3.1. Transition from IoT to AIoT in Agriculture

3.2. Technological Enablers

3.3. Challenges in System Evolution

3.4. Regional Perspectives: Adoption in Africa

3.5. Challenges in AIoT for African Agriculture: A Data, Feature, and Model Perspective

3.5.1. Data Study Challenges

- Scarcity and Sparsity: There is a pervasive lack of large-scale, historical, and digitized agricultural datasets. Data collection is often project-based, resulting in temporally and spatially sparse records insufficient for training robust, generalizable models.

- Heterogeneity and Inconsistency: Data streams originate from a mosaic of low-cost sensors, satellite platforms with varying resolutions, and manual entries. This leads to significant challenges in data fusion due to inconsistencies in format, calibration, sampling frequency, and accuracy.

- Ground Truth Acquisition: Supervised learning requires accurately labeled data. The process of obtaining ground truth for agronomic variables (e.g., pest species, soil nutrient levels, yield) is costly, time-consuming, and relies on scarce local expertise, creating a major bottleneck for model development.

- Privacy, Ownership, and Governance: Ambiguity surrounding data ownership can deter farmers from participating in data-sharing initiatives, particularly when coupled with fears of exploitation. The absence of clear, farmer-centric data governance frameworks undermines both trust and the ethical foundation of AIoT systems.

3.5.2. Feature Study Challenges

- Domain-Specific Engineering: Identifying predictive features requires deep cross-disciplinary knowledge that bridges data science, agronomy, and local ecological understanding. This expertise gap can lead to the use of suboptimal or irrelevant features.

- Contextual Variability and Dimensionality: Agro-ecological conditions vary dramatically across Africa. Features that are predictive in one region may be irrelevant in another. Furthermore, multi-sensor fusion creates high-dimensional data, risking redundancy and increased computational load for edge processing.

- Real-Time Extraction Constraints: For edge-based intelligence, feature extraction algorithms must be extremely lightweight. Complex statistical or spectral features that are standard in cloud analytics may be infeasible on resource-constrained microcontrollers, necessitating significant innovation in efficient feature design.

3.5.3. Model Study Challenges

- Poor Generalization and Transferability: Models trained on data from one geographic or climatic context often fail to generalize to others due to differences in soil, crop varieties, weather patterns, and management practices. Developing adaptable or transferable models is a core research challenge.

- Computational and Energy Bottlenecks: Deploying state-of-the-art models on low-power edge devices (TinyML) requires aggressive model compression (pruning, quantization). This process involves a delicate trade-off between model accuracy, size, and inference speed, which is critical for real-time decision-making.

- The Black Box Problem and Trust Deficit: The opacity of complex models like deep neural networks erodes farmer trust. When recommendations cannot be intuitively explained or linked to observable field conditions, adoption is severely hindered.

- Model Maintenance and Concept Drift: Agricultural systems are non-stationary. Climate change, evolving pest biotypes, and changing soil conditions can cause model performance to degrade over time (concept drift). Establishing sustainable pipelines for model monitoring and retraining in off-grid settings is a significant operational challenge.

3.6. Opportunities in AIoT for African Agriculture: Innovating Within Constraints

3.6.1. Opportunities in Data Study

- Participatory and Crowdsourced Data Collection: The ubiquity of mobile phones enables farmer-centric data generation. Through structured apps, farmers can contribute labeled images, yield reports, and management logs. This approach builds rich, contextual datasets while enhancing digital literacy and engagement.

- Leveraging Open and Satellite Data: The proliferation of free, high-resolution earth observation data (e.g., Sentinel-2, NASA SERVIR) provides a foundational, continent-wide data layer. Fusing this data with sparse ground sensor measurements through advanced imputation and fusion techniques can mitigate initial data scarcity.

- Blockchain for Transparency and Equity: Blockchain and distributed ledger technologies can establish transparent data provenance, immutable usage records, and smart contracts for fair data valuation. These technologies can empower farmers by giving them control over their data and potential revenue streams.

- Synthetic Data Generation: For rare events (e.g., specific pest outbreaks) or to balance datasets, techniques like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can create realistic synthetic agricultural data, safely augmenting training sets and improving model robustness.

3.6.2. Opportunities in Feature Study

- Automated Feature Learning: Instead of manual engineering, deep learning architectures (e.g., autoencoders, 1D-CNNs for time-series) can be trained to automatically discover optimal, compressed feature representations directly from raw sensor data, even when noisy.

- Ethno-Computing and Domain Fusion: Collaborative design with farmers and agronomists can yield ethno-features computable representations of indigenous knowledge and observational cues. This fusion of local wisdom with data science ensures features are both interpretable and agronomically sound.

- Development of Transferable Feature Spaces: Research can focus on learning feature embeddings that are invariant to specific locales but sensitive to universal agricultural states (e.g., water-stressed, nutrient-deficient). This would enhance model portability across diverse African agro-ecologies.

- Ultra-Lightweight Feature Algorithms: There is a significant opportunity to design novel, computationally trivial algorithms for calculating key agronomic indices (e.g., vegetation indices, soil water content estimators) directly on edge devices, enabling sophisticated analytics without cloud dependence.

3.6.3. Opportunities in Model Study

- Explainable AI (XAI) and Hybrid Models: The integration of XAI is imperative. Hybrid modeling, which combines data-driven ML with mechanistic crop models or rule-based expert systems, can enhance interpretability, improve performance with limited data, and build farmer trust by aligning with causal understanding.

- Federated Learning: This paradigm enables collaborative model training across multiple farms without centralizing raw data. It preserves data privacy, leverages diverse local data distributions, and builds collective intelligence ideal for cooperatives and farmer networks.

- Few-Shot and Meta-Learning: These approaches aim to create models that can rapidly adapt to new tasks (e.g., recognizing a new disease) with only a few examples. This is crucial for responsive pest and disease management in dynamic environments.

- Edge-Native Model Architectures: Beyond compressing cloud models, the future lies in designing edge-native models. This involves neural architecture search (NAS) for efficient topologies and training strategies that prioritize low-power inference, robustness to sensor noise, and adaptive learning from streaming data.

4. Key AIoT Applications in Smart Farming

5. Proposed AIoT Architecture for African Agriculture

5.1. Layered Architecture Overview

5.2. Benefits for Low-Income and Sub-Saharan Agriculture

5.3. Prerequisites for Successful Deployment in Africa

5.4. Expected Productivity Gains

6. Ethical Aspects of AIoT in Agriculture

7. Discussion

8. Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AIoT | Artificial Intelligence of Things |

| AWS | Amazon Web Services |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| GPRS | General Packet Radio Service |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GSM | Global System for Mobile Communications |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LoRa | Long Range |

| LPWAN | Low Power Wide Area Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| NB-IoT | Narrowband Internet of Things |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| PLF | Precision Livestock Farming |

| PPP | Public–Private Partnerships |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SMS | Short Message Service |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| USD | United States Dollar |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A. Key Terminology

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) | Integration of artificial intelligence capabilities (machine learning, computer vision, predictive analytics) with IoT infrastructure to enable autonomous decision-making, pattern recognition, and intelligent responses in connected systems. |

| Climate Resilience | The capacity of agricultural systems to anticipate, absorb, adapt to, and recover from climate-related shocks and stresses (droughts, floods, temperature extremes) while maintaining productivity and sustainability. |

| Digital Divide | The gap in access to digital technologies, infrastructure, and literacy between well-resourced populations and resource-constrained communities, particularly affecting smallholder farmers in developing regions. |

| Edge Computing | Distributed computing paradigm where data processing occurs at or near the data source (the network edge) rather than in centralized cloud servers, enabling real-time decision-making with reduced latency and bandwidth requirements. |

| Governance Frameworks | Structured policies, regulations, and institutional arrangements that guide data ownership, privacy protection, algorithmic accountability, and ethical use of AI technologies in agricultural systems. |

| LPWAN (Low-Power Wide-Area Network) | Wireless communication technologies (e.g., LoRaWAN, NB-IoT, Sigfox) designed for long-range transmission (2–15 km) with minimal power consumption, ideal for connecting battery-powered IoT devices in remote agricultural areas. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Computational methods and algorithms that enable systems to learn patterns from data and improve performance on specific tasks without being explicitly programmed, including techniques such as neural networks, decision trees, and support vector machines. |

| Precision Agriculture | Farming management approach that uses data-driven technologies to optimize field-level crop and livestock management with regard to spatial and temporal variability, minimizing resource waste while maximizing productivity. |

| Smart Livestock Management | Technology-enabled monitoring and management of animal health, welfare, behavior, and productivity using sensors, wearables, and AI analytics to optimize herd performance and detect early signs of illness or stress. |

| TinyML | Machine learning techniques optimized to run on resource-constrained microcontrollers and embedded devices with limited memory, processing power, and energy availability, typically consuming less than 1mW of power. |

References

- Oliveira, R.C.d.; Silva, R.D.d.S.e. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture: Benefits, Challenges, and Trends. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Ammad-Uddin, M.; Sharif, Z.; Mansour, A.; Aggoune, E.H.M. Internet-of-Things (IoT)-based smart agriculture: Toward making the fields talk. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 129551–129583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine learning in agriculture: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Xu, L. Edge computing: Vision and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016, 3, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, P.; Ranganath, S.; Bhandaru, M.; Tibrewala, S. A Survey of AI Enabled Edge Computing for Future Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th 5G World Forum (5GWF), Montreal, QC, Canada, 13–15 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, R.; Manne, N.; Garg, J.; Motwani, D.; Shrivastava, A.K.; Sharma, M. A Smart Irrigation System Powered by IoT and Machine Learning for Optimal Water Management. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE), Greater Noida, India, 14–15 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1801–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.P.; Hughes, D.P.; Salathé, M. Using deep learning for image-based plant disease detection. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajib, M.M.H.; Sayem, A.S.M. Innovations in Sensor-Based Systems and Sustainable Energy Solutions for Smart Agriculture: A Review. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yue, M.; Yao, H.; Tian, H.; Sun, X.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ban, D.; Zheng, H. Hybridized energy harvesting device based on high-performance triboelectric nanogenerator for smart agriculture applications. Nano Energy 2022, 102, 107681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Hasan, W.; Singh, S.; Kumar, D.; Ansari, M.J.; Nisar, S. (Eds.) Agriculture 4.0: Smart Farming with IoT and Artificial Intelligence; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsan, M.; Totapally, S.; Hailu, M.; Addom, B.K. The Digitalisation of African Agriculture Report 2018–2019; CTA/Dalberg Advisers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2022; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/101498 (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Lee, S.W.; Koo, M.J. PRISMA 2020 statement and guidelines for systematic review and meta-analysis articles, and their underlying mathematics: Life Cycle Committee Recommendations. Life Cycle 2022, 2, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.A. When AI Meets IoT: AIoT. In Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2022; p. ch. 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RINF Tech. Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT): Current State and Future Path. 2023. Available online: https://www.rinf.tech/artificial-intelligence-of-things-aiot-current-state-and-future-path/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Kasereka, S.K.; Tashev, T.; Medagbe, Y.C.N.; Ocama, O.V.; Ilunga, G.W.; Kyungu, E.; Kyamakya, K. Smart Irrigation for Precision Agriculture: A Pathway to Sustainable Farming in Low-Income Regions. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Big Data, Knowledge and Control Systems Engineering (BdKCSE), Bankya, Bulgaria, 6–7 November 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, I. AIoT: When Artificial Intelligence Meets the Internet of Things. 2020. Available online: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/aiot-when-ai-meets-iot-technology/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Chlingaryan, A.; Sukkarieh, S.; Whelan, B. Machine learning approaches for crop yield prediction and nitrogen status estimation in precision agriculture: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 151, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.; Maltese, A.; McCabe, M.F. Monitoring agricultural ecosystems. In Unmanned Aerial Systems for Monitoring Soil, Vegetation, and Riverine Environments; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Medagbe, Y.C.N.; Ocama, O.V.; Kasoro, N.M.; Tashev, T.; Kasereka, S.K. Leveraging Smart Crop Recommendation Systems and Climate-Resilient Practices for Sustainable Agriculture in Developing Regions: A Brief Review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 265, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazie, I.G.; Mbayandjambe, A.M.; Nguemdjom, K.T.; Kuyunsa, A.M.; Kabengele, H.K.; Gupta, R.; Kyamakya, K.; Tashev, T.; Kasereka, S.K. Enhancing Agricultural Supply Chain Traceability with Blockchain, Smart Contracts, and E-Labelling. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Big Data, Knowledge and Control Systems Engineering (BdKCSE), Bankya, Bulgaria, 6–7 November 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goap, A.; Sharma, D.; Shukla, A.; Krishna, C. An IoT based smart irrigation management system using Machine learning and open source technologies. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 155, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocama, O.V.; Medagbe, Y.C.N.; Akello, S.; Kambale, W.V.; Tashev, T.; Kyamakya, K.; Kasereka, S.K. A Review on Advancing Technologies in Precision Agriculture: Applications, Challenges, and the Way Forward. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 265, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S.; Reimert, I.; Kemp, B. Recent advances in wearable sensors for animal health management. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2021, 32, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintus, M.; Colucci, F.; Maggio, F. Emerging Developments in Real-Time Edge AIoT for Agricultural Image Classification. IoT 2025, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adli, H.K.; Remli, M.A.; Wong, K.N.S.W.S.; Ismail, N.A.; González-Briones, A.; Corchado, J.M.; Mohamad, M.S. Recent Advancements and Challenges of AIoT Application in Smart Agriculture: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, E.E.K.; Anggraini, L.; Kumi, J.A.; Karolina, L.B.; Akansah, E.; Sulyman, H.A.; Mendonça, I.; Aritsugi, M. IoT Solutions with Artificial Intelligence Technologies for Precision Agriculture: Definitions, Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Electronics 2024, 13, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, J.; Ali, N.; Cao, Z.; Ren, Y.; Dong, Y. Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) for Precision Agriculture: Applications in Smart Irrigation, Nutrient and Pest Management. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tace, Y.; Tabaa, M.; Elfilali, S.; Leghris, C.; Bensag, H.; Renault, E. Smart irrigation system based on IoT and machine learning. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsoh, B.; Katimbo, A.; Guo, H.; Heeren, D.M.; Nakabuye, H.N.; Qiao, X.; Ge, Y.; Rudnick, D.R.; Wanyama, J.; Bwambale, E.; et al. Internet of Things-Based Automated Solutions Utilizing Machine Learning for Smart and Real-Time Irrigation Management: A Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 7480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoaib, M.; Sadeghi-Niaraki, A.; Ali, F.; Hussain, I.; Khalid, S. Leveraging deep learning for plant disease and pest detection: A comprehensive review and future directions. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1538163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyakuri, J.P.; Nkundineza, C.; Gatera, O.; Nkurikiyeyezu, K.; Mwitende, G. AI and IoT-powered edge device optimized for crop pest and disease detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasath, B.; Akila, M. IoT-based pest detection and classification using deep features with enhanced deep learning strategies. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 105985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.J.; Rayanoothala, P.S.; Sree, R.P. Next-gen agriculture: Integrating AI and XAI for precision crop yield predictions. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1451607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabed, M.A.; Murad, M.A.A. Crop yield prediction in agriculture: A comprehensive review of machine learning and deep learning approaches. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.F.; Sabanci, K.; Aslan, B. Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Crop Yield Estimation Based on Sentinel-2 Data: A Comprehensive Survey. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terence, S.; Immaculate, J.; Raj, A.; Nadarajan, J. Systematic Review on Internet of Things in Smart Livestock Management Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangorra, F.M.; Buoio, E.; Calcante, A.; Bassi, A.; Costa, A. Internet of Things (IoT): Sensors Application in Dairy Cattle Farming. Animals 2024, 14, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamuryekung’e, S. Transforming ranching: Precision livestock management in the Internet of Things era. Rangelands 2024, 46, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigussie, E.; Olwal, T.; Musumba, G.; Tegegne, T.; Lemma, A.; Mekuria, F. IoT-based Irrigation Management for Smallholder Farmers in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 177, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngulube, P. Leveraging information and communication technologies for sustainable agriculture and environmental protection among smallholder farmers in tropical Africa. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehui, S.K.; Odeh, K. Digital Solutions in Agriculture Drive Meaningful Livelihood Improvements for African Smallholder Farmers; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/digital-solutions-in-agriculture-drive-meaningful-livelihood-improvements-for-african-smallholder-farmers/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Farmonaut. Africa Agri Tech 2025: Transforming Agriculture Africa. 2025. Available online: https://farmonaut.com/africa/africa-agri-tech-2025-transforming-agriculture-africa (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Wambua, R. Will AI Make Farming in Africa More Sustainable or More Complex? 2025. Available online: https://lanfrica.com/blog/will-ai-make-farming-in-africa-more-sustainable-or-more-complex/ (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- Uyeh, D.D.; Gebremedhin, K.G.; Hiablie, S. Perspectives on the strategic importance of digitalization for Modernizing African Agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 211, 107972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onike, N.J. The Internet of Things (IoT) in Farming: Smart Solutions for a Sustainable Future. Int. J. Poverty Investig. Dev. 2025, 5, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Africa, T.I. How IoT Sensors Improve Crop Yields in Africa. 2024. Available online: https://www.techinafrica.com/how-iot-sensors-improve-crop-yields-in-africa/ (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Africa, I.N. Benefits of IoT in Agriculture and Farming. 2025. Available online: https://www.itnewsafrica.com/2025/04/benefits-of-iot-in-agriculture-and-farming/ (accessed on 19 January 2026).

- Africa, T.R. IoT Innovations Driving Smart Agriculture Solutions on the African Continent. 2024. Available online: https://www.telecomreviewafrica.com/articles/features/12729-iot-innovations-driving-smart-agriculture-solutions-on-the-african-continent/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Dahane, A.; Benameur, R.; Kechar, B. An IoT low-cost smart farming for enhancing irrigation efficiency of smallholders farmers. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2022, 127, 3173–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review, S.E. AI in Agriculture: Transforming Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2025. Available online: https://stanfordeconreview.com/2025/03/12/commentary-ai-in-agriculture-transforming-food-security-in-sub-saharan-africa/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Abdulai, A.R.; Quarshie, P.T.; Duncan, E.; Fraser, E. Is agricultural digitization a reality among smallholder farmers in Africa? Unpacking farmers’ lived realities of engagement with digital tools and services in rural Northern Ghana. Agric. Food Secur. 2023, 12, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Dara, R.; Hazrati Fard, S.M.; Kaur, J. Recommendations for ethical and responsible use of artificial intelligence in digital agriculture. Front. Artif. Intell. 2022, 5, 884192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T.; Mikiciuk, G.; Durlik, I.; Mikiciuk, M.; Łobodzińska, A.; Śnieg, M. The IoT and AI in Agriculture: The Time Is Now—A Systematic Review of Smart Sensing Technologies. Sensors 2025, 25, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwelo, F.A. Algorithmic Bias and Farmers’ Autonomy in AI-Driven Agricultural Marketing and Supply Chains. In AI and Machine Learning Applications in Supply Chains and Marketing; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 313–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayuravaani, M.; Ramanan, A.; Perera, M.; Senanayake, D.A.; Vidanaarachchi, R. Insights into artificial intelligence bias: Implications for agriculture. Digit. Soc. 2024, 3, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewera, D.; Zhou, M.; Gavai, P.V. Enhancing IoT Security for Socio-Economic Development in the Mirror of Challenges, Emerging Technologies, and Holistic Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd Zimbabwe Conference of Information and Communication Technologies (ZCICT), Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, 28–29 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, R. Ecological footprints, carbon emissions, and energy transitions: The impact of artificial intelligence (AI). Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, A.O.; Adediran, S.A.; Omotoso, A.B.; Olagunju, K.O.; Omotayo, O.P. Artificial intelligence in agriculture: Ethics, impact possibilities, and pathways for policy. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 110927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, S.; Spachos, P. Solar-powered smart agricultural monitoring system using Internet of Things devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 9th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1–3 November 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Refs | Key Contributions | Study Scope | Technology Used | Dataset | Country | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IoT to AIoT Evolution/Paradigm Papers | ||||||

| [24] | Reviews edge-based AIoT deployment workflow for agricultural monitoring; Highlights data seasonality and power consumption challenges in edge AI. | IoT-AIoT evolution; Edge computing | Deep learning models, edge devices | Literature review | Global | Data seasonality limits model training; Power consumption concerns; Early development stage. |

| [25] | Systematic review tracking AIoT field growth from <5 papers (2017) to 50 papers (2023); Identifies AIoT as distinct paradigm beyond IoT+AI. | IoT-AIoT evolution; Smart agriculture | Deep learning, computer vision, IoT sensors | Literature review (37,230 AI/IoT agriculture articles) | Global | AIoT in infant stage; Adoption barriers; Data acquisition and connectivity challenges. |

| [26] | PRISMA 2020 systematic review demonstrating sharp publication increase 2022–2024; Comprehensive communication technology analysis. | IoT-AI integration; Precision agriculture | LoRa, NB-IoT, GSM/GPRS, IoT sensors | Literature review (PRISMA 2020) | Global | Rural connectivity challenges; Limited cellular coverage; Edge computing needs optimization. |

| AIoT Applications-Smart Irrigation | ||||||

| [27] | Reviews AIoT applications showing 35% water waste reduction; Integrates UAV technology with AI analytics for precision management. | Smart irrigation; Nutrient management | UAVs, AI analytics, soil moisture sensors | Literature review | Global | High setup costs; Rural connectivity issues; Inconsistent sensor reliability; Limited smallholder scalability. |

| [28] | Designs an IoT- and ML-based smart irrigation system to optimize water use through real-time sensing and predictive decision-making. | Smart irrigation; IoT–ML water management | Soil moisture sensors, microcontroller/IoT nodes, wireless communication, ML prediction models | Custom experimental sensor dataset | Morocco | Limited dataset size; field validation constrained; performance depends on sensor reliability; scalability and long-term deployment not fully assessed. |

| [29] | PRISMA review of 43 studies showing LSTM achieving R2 0.76–0.91 for soil moisture prediction; Reports 20% pesticide reduction, 30% water savings. | Smart irrigation; Predictive analytics | LSTM networks, IoT sensors, ML algorithms | Literature review (43 studies 2017–2024) | Global | Field transferability issues; Manual steps required; High ML computational demands; Limited complex validation. |

| AIoT Applications-Pest Detection | ||||||

| [30] | Comprehensive review of CNN-based models achieving >95% classification accuracy and >90% detection precision for plant diseases. | Pest detection; Disease classification | CNNs, computer vision, deep learning | Literature review | Global | Environmental factors affect performance; Limited real-world validation; Large labeled datasets required; Occlusion challenges. |

| [31] | Develops portable edge device (Raspberry Pi 5) with Tiny-LiteNet CNN for resource-constrained African environments; Built-in explainability. | Pest detection; Edge AI | Raspberry Pi 5, Tiny-LiteNet CNN, lightweight models | Cereal crops dataset | Rwanda | Limited to cereal crops; HD camera required; Edge processing limitations; Climate change requires updates. |

| [32] | Novel IoT-based pest detection model with enhanced deep learning achieving higher accuracy than existing methods. | Pest detection; IoT classification | IoT sensors, enhanced deep learning, object detection | Custom IoT sensor data | India | Day/night pest hiding; Image quality sensor-dependent; High computational demands; Limited pest types. |

| AIoT Applications-Crop Yield Prediction | ||||||

| [33] | Integrates Explainable AI (XAI) with CNNs for transparent yield prediction using satellite/drone imagery for climate adaptation. | Crop yield prediction; XAI | CNNs, XAI, satellite/drone imagery, multispectral sensors | Satellite/drone imagery | Global | Requires high-resolution imagery; Complex training/validation; Limited developing region access; High computational needs. |

| [34] | Comprehensive review analyzing 115 articles on ML/DL methods for yield prediction; Notable advancement documented 2018–2023. | Crop yield prediction; ML/DL comparison | Random Forest, XGBoost, CNNs, LSTM | Literature review (115 articles) | Global | Data availability issues; Limited regional transferability; Substantial historical data needed; High computational resources. |

| [35] | Reviews AI integration with free Sentinel-2 satellite data for yield estimation; Continuous study increase 2017–2024. | Crop yield prediction; Satellite imagery | Random Forests, SVM, CNNs, Sentinel-2 multispectral | Sentinel-2 satellite data (wheat, maize, rice) | Global | Cloud cover affects quality; 5-day temporal limits; Ground truth validation required; Technical expertise needed. |

| AIoT Applications-Livestock Management | ||||||

| [36] | PRISMA systematic review covering sensors, actuators, controllers for multiple animal types; Addresses renewable energy integration. | Livestock management; IoT systems | IoT sensors, actuators, controllers, communication tech | Literature review (PRISMA) | Global | Single animal focus common; Limited scalability analysis; Stability/maintenance gaps; Economic feasibility unclear. |

| [37] | Reviews Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) device integration with edge/cloud computing and ML for dairy cattle real-time monitoring. | Livestock management; Dairy cattle | PLF devices, edge/cloud computing, ML, IoT sensors | Dairy cattle sensor data | Italy | High edge device costs; Regular updates required; Limited farm expertise; Heterogeneous adoption rates. |

| [38] | Examines precision livestock management integrating on-animal sensors, environmental monitoring, remote sensing for ranching. | Livestock management; Ranching | On-animal sensors, environmental monitoring, remote sensing, IoT | Rangeland sensor data | United States | Landscape connectivity challenges; Harsh conditions threaten devices; High implementation costs; Training requirements. |

| African Context Papers | ||||||

| [39] | Examines IoT irrigation solutions tailored for smallholder farmers in low-bandwidth Sub-Saharan Africa environments. | Smart irrigation; Smallholder focus | IoT sensors, low-bandwidth solutions | Not specified | Sub-Saharan Africa | Limited rural infrastructure; High upfront costs; Connectivity challenges; Limited technical support. |

| [40] | Explores ICT tools for sustainable agriculture and environmental protection among tropical Africa smallholder farmers. | ICT for sustainability; Environmental protection | ICT tools, digital agriculture technologies | Not specified | Tropical Africa | Rural infrastructure gaps; Digital literacy challenges; Affordability issues; Limited support networks. |

| [41] | Policy analysis demonstrating evidence-based livelihood improvements from digital agricultural solutions for African smallholders. | Digital agriculture policy; Livelihood improvement | Digital agricultural technologies | Not specified | Africa | Policy requires government action; Barriers not fully addressed; Scalability challenges; Funding concerns. |

| [42] | Industry overview of agri-tech transformation trends covering technological innovations and market opportunities in Africa for 2025. | Agri-tech trends; Market analysis | Various agricultural technologies | Not specified | Africa | May lack academic rigor; Limited peer review; May emphasize opportunities over challenges; Commercial bias. |

| [43] | Critical examination of AI’s dual potential as sustainability enabler and complexity creator in African agriculture. | AI sustainability; Complexity analysis | AI technologies in agriculture | Not specified | Africa | Blog lacks peer review; May lack empirical data; Limited technical depth; Solutions underdeveloped. |

| [44] | Strategic analysis examining digitalization policy implications, infrastructure requirements, and socio-economic adoption factors in Africa. | Digitalization strategy; Policy analysis | Digital agricultural technologies | Not specified | Africa | Abstract-only access limits assessment; General roadmap; Regional diversity challenges; Funding unexplored. |

| [45] | Examines IoT farming applications emphasizing sustainability and future-oriented solutions for developing world contexts. | IoT sustainability; Future solutions | IoT sensors, smart farming technologies | Not specified | Nigeria | Limited impact factor; Review rigor uncertain; African-specific content unclear; Technical depth unspecified. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kasereka, S.K.; Mbayandjambe, A.M.; Bazie, I.G.; Zeufack, H.F.; Ocama, O.V.; Hassan, E.; Kyamakya, K.; Tashev, T. From IoT to AIoT: Evolving Agricultural Systems Through Intelligent Connectivity in Low-Income Countries. Future Internet 2026, 18, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18020082

Kasereka SK, Mbayandjambe AM, Bazie IG, Zeufack HF, Ocama OV, Hassan E, Kyamakya K, Tashev T. From IoT to AIoT: Evolving Agricultural Systems Through Intelligent Connectivity in Low-Income Countries. Future Internet. 2026; 18(2):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18020082

Chicago/Turabian StyleKasereka, Selain K., Alidor M. Mbayandjambe, Ibsen G. Bazie, Heriol F. Zeufack, Okurwoth V. Ocama, Esteve Hassan, Kyandoghere Kyamakya, and Tasho Tashev. 2026. "From IoT to AIoT: Evolving Agricultural Systems Through Intelligent Connectivity in Low-Income Countries" Future Internet 18, no. 2: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18020082

APA StyleKasereka, S. K., Mbayandjambe, A. M., Bazie, I. G., Zeufack, H. F., Ocama, O. V., Hassan, E., Kyamakya, K., & Tashev, T. (2026). From IoT to AIoT: Evolving Agricultural Systems Through Intelligent Connectivity in Low-Income Countries. Future Internet, 18(2), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18020082