Unsupervised Detection of SOC Spoofing in OCPP 2.0.1 EV Charging Communication Protocol Using One-Class SVM

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Implications of Spoofing SOC

1.1.1. Unfair Scheduling

1.1.2. Charging Station Congestion

1.1.3. Inaccurate Load Forecasting

2. Related Work on EV SOC-Based Frameworks and Their Challenges

2.1. Charging Scheduling and Optimization

2.2. Demand Response Program

2.3. V2G and Ancillary Services

2.4. Contributions

- We identify and define two SOC spoofing attacks (i.e., Priority Manipulation Attack and Session Extension Attack) and explain how adversaries can manipulate SOC values to obtain unfair charging priority, get around charging cutoff policies, and cause inaccurate wait time estimation, charging station congestion, and even grid instability.

- Building on our preliminary studies on SOC-based spoofing attacks presented in [29], where we only achieved an F1 score of 87% with an autoencoder-based attack detection model without engineered features, in this paper, we focus on deriving engineered features and present the need for the specific features that we engineered.

- We propose an unsupervised learning-based spoofing attack detection model based on One-Class SVM (OCSVM), which can detect both spoofing attacks with high accuracy.

- We compare the performance of our proposed OCSVM-based attack detection model with alternative unsupervised learning and deep learning-based attack detection models and present a detailed tradeoff analysis of precision and recall in terms of the two defined spoofing attacks and their consequences.

3. Background and Threat Model

3.1. OCPP 2.0.1 Overview

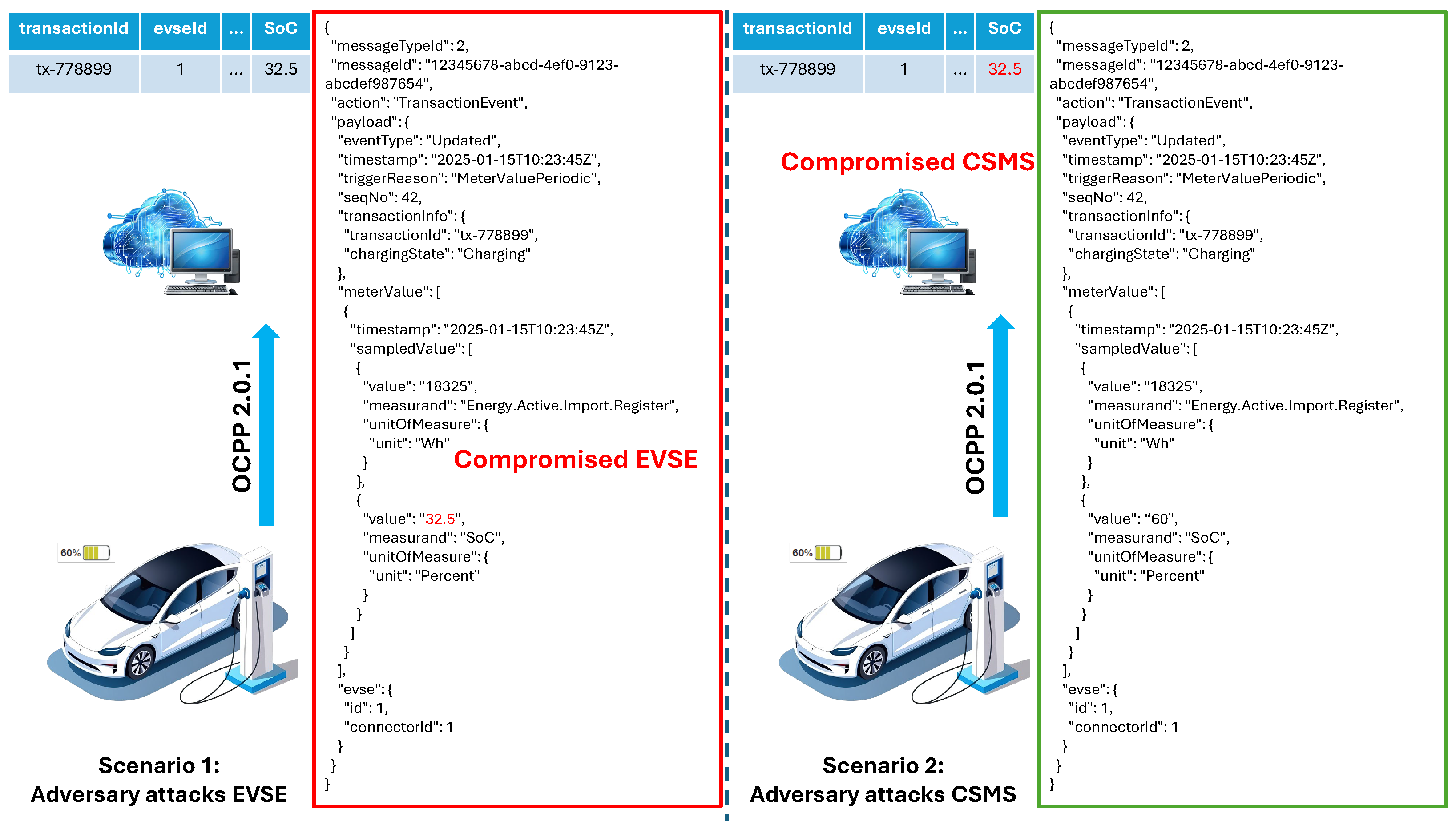

3.2. Threat Model

- Priority Manipulation Attack: In this attack, the adversary falsifies its SOC upon arrival, commonly referred to as the arrival SOC. By falsely reporting a significantly lower arrival SOC than the true value, it may appear that the EV requires charging immediately. This deception can mislead the charging station or aggregator into prioritizing the EV for immediate or accelerated charging [9,10], granting it unfair access to resources ahead of others. Such manipulation disrupts optimal scheduling mechanisms and can make the charging infrastructure less reliable overall. Since aggregators may unknowingly allocate excess resources to malicious users while neglecting genuinely low-SOC vehicles, if such vulnerability persists over time, the charging station/aggregator may start losing user trust and may lead to financial losses for charging service operators.

- Session Extension Attack: In this attack, the adversary falsifies the SOC near the end of the charging session, reporting it as lower than its true value. Typically, charging stations or aggregators enforce a cutoff of the charging session once the SOC exceeds a predefined threshold (e.g., around 85%) [11], since charging efficiency declines sharply beyond this point due to a lower charging rate. Specifically, each additional percent of SOC requires disproportionately more time. By falsifying its SOC, the attacker can bypass this cutoff policy since the station believes further charging may be required, thus, allowing the EV to remain connected to charge. This can lead to charging station congestion because the charging station miscalculates the wait times. Inaccurate wait times can cause customer dissatisfaction as other customers may stay in the queue longer than it was promised, overall degrading the reliability of the charging infrastructure. The consequences of the Session Extension attack extend beyond congestion at the individual charging stations, as the inaccurate wait times may propagate delays across the entire charging network when EVs start moving to other charging stations. The effects may propagate faster in urban environments, where the EV density is typically higher. This cascading effect will cause serious degradation and trust of customers in EV charging stations. Furthermore, falsified SOC data can corrupt the load forecast, which can, in a result, disrupt load balancing. This can potentially lead to voltage fluctuations and grid instability, where the consequences can be significant during peak demand periods.

4. One-Class SVM-Based Anomaly Detection

4.1. One-Class SVM Background

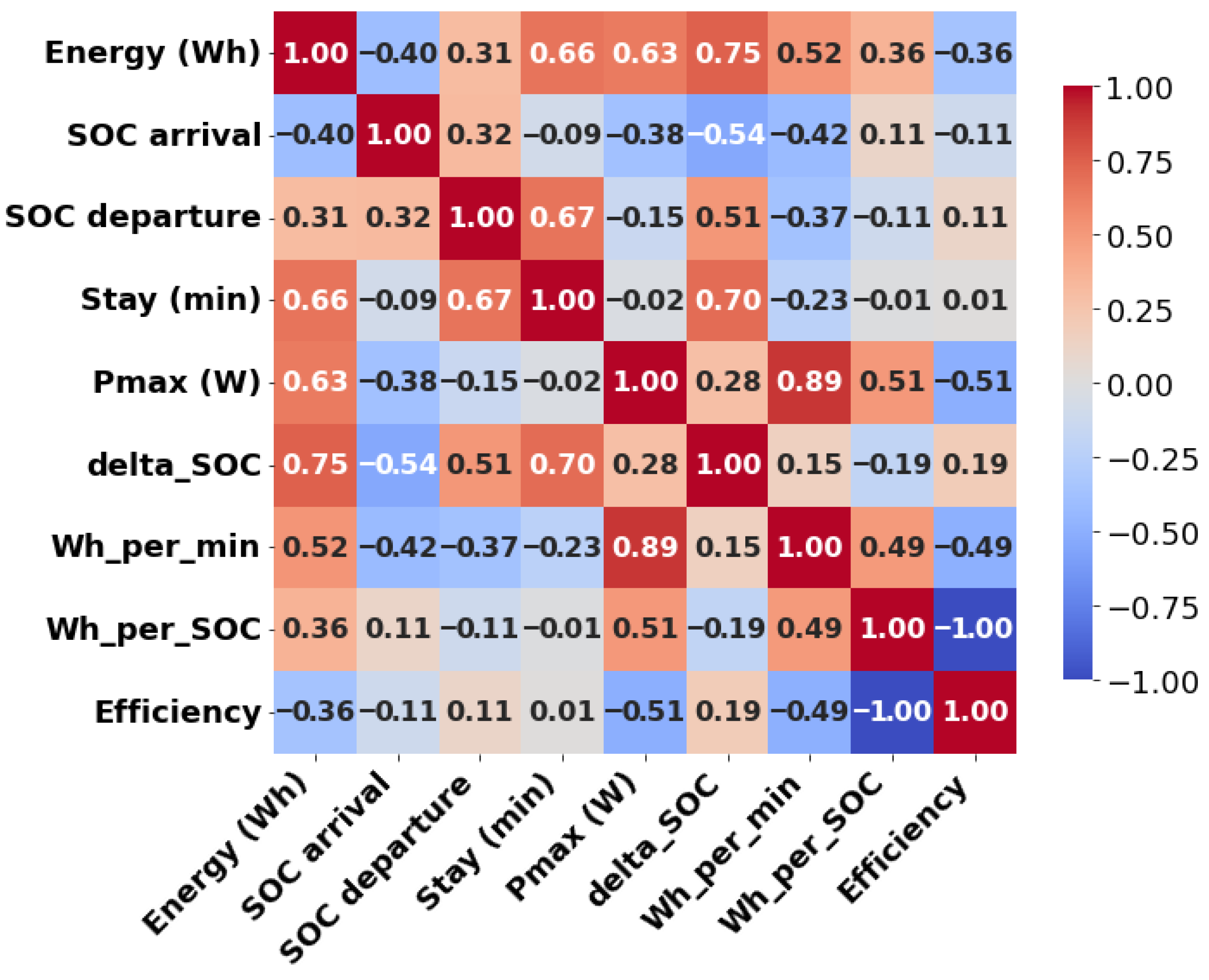

4.2. Dataset Construction and Feature Engineering

5. Performance Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

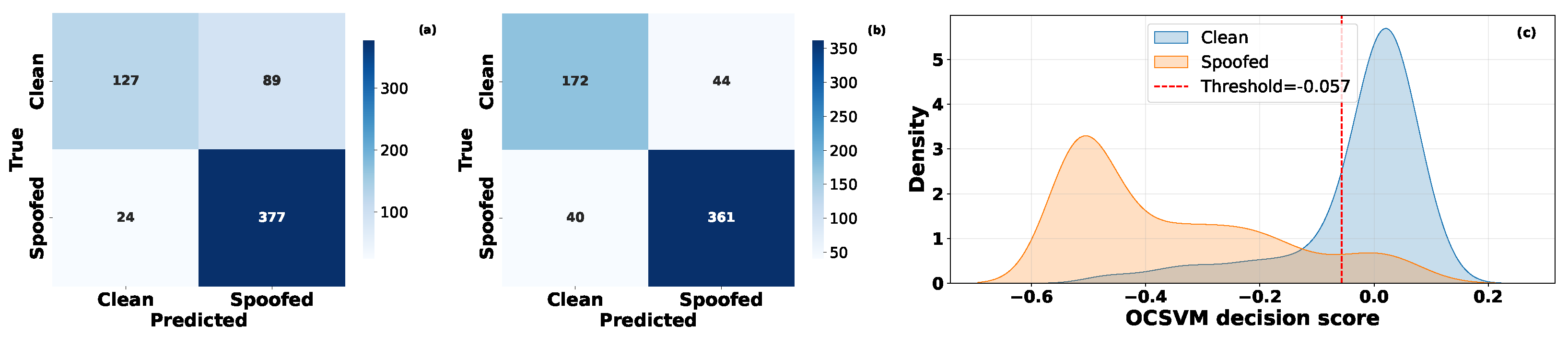

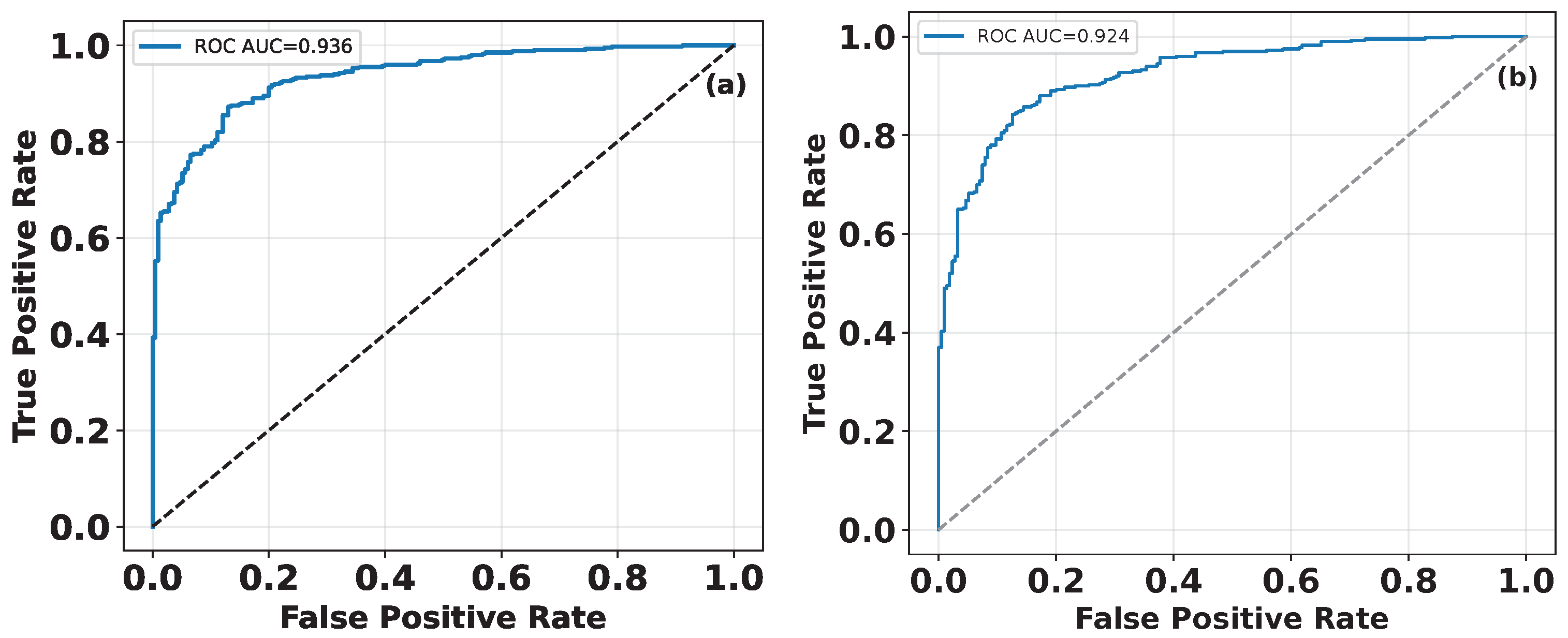

5.2. Performance Evaluation of OCSVM for Spoofing Attack Detection

5.3. Comparative Evaluation

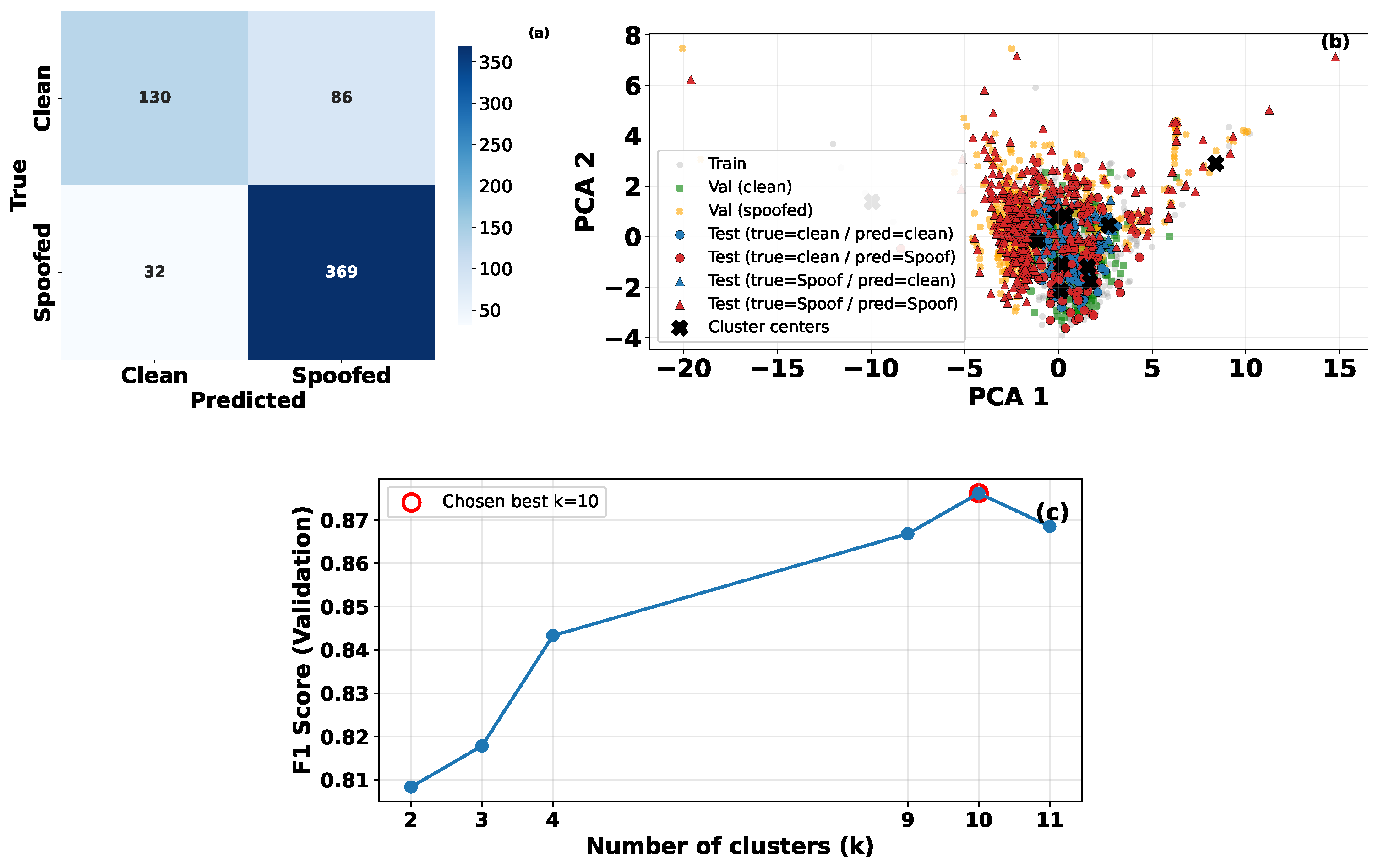

5.3.1. K-Means Clustering for Spoofing Attack Detection

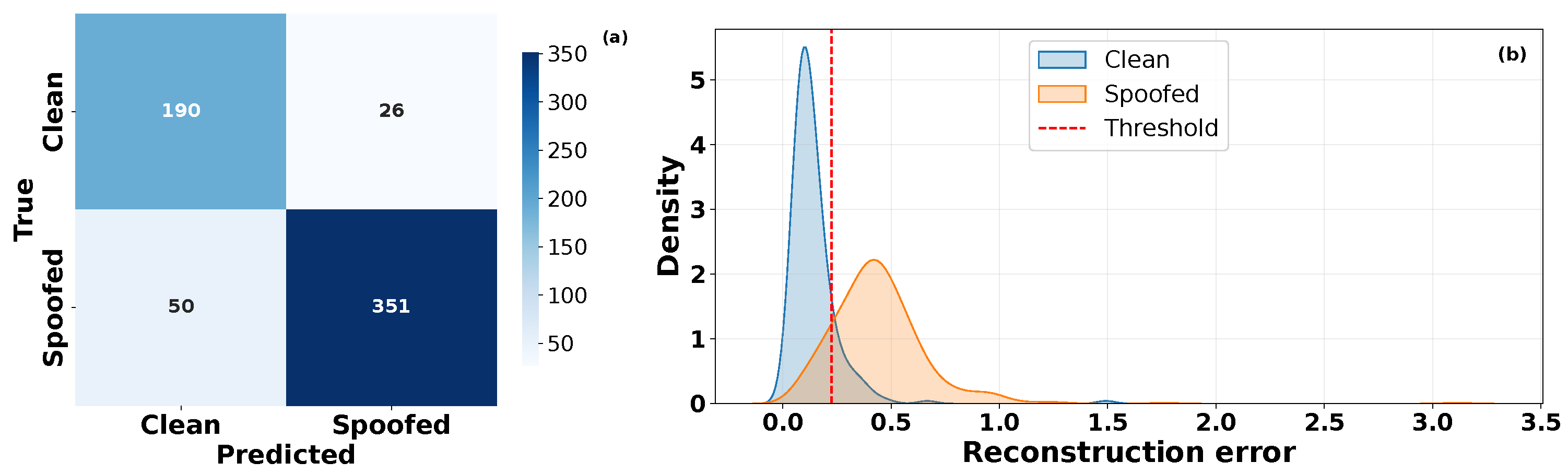

5.3.2. Autoencoder for Spoofing Attack Detection

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shankleman, J. The Electric Car Revolution Is Accelerating; Bloomberg: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gd-Admin. Global EV Charging Station Market Is Projected to Reach USD 12.1 Billion by 2030. Available online: https://www.midaevse.com/news/global-ev-charging-station-market-is-projected-to-reach-usd-12-1-billion-by-2030/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Anwar, M.N.B.; Ruby, R.; Cheng, Y.; Pan, J. Time-of-Use-Aware Priority-Based Multi-Mode Online Charging Scheme for EV Charging Stations. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm), Singapore, 25–28 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hakak, S.; Ghorbani, A. Detecting Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks that generate false authentications on Electric Vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure. Comput. Secur. 2024, 144, 103989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Panigrahi, B.K.; Joshi, A.; Paul, K. Demonstration of denial of charging attack on electric vehicle charging infrastructure and its consequences. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2024, 46, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, T.; Torabi, S.; Bou-Harb, E.; Fachkha, C.; Assi, C. Power jacking your station: In-depth security analysis of electric vehicle charging station management systems. Comput. Secur. 2022, 112, 102511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, M.; Kabir, M.E.; Moussa, B.; Assi, C. Coordinated Charging and Discharging of Electric Vehicles: A New Class of Switching Attacks. ACM Trans. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2022, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, S.S.A.; Raj, V.; Petra, M.I.; Azad, A.K.; Mathew, S.; Sulthan, S.M. Charge Scheduling Optimization of Electric Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review of Essentiality, Perspectives, Techniques, and Security. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 121010–121034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, B.; Cao, B.; Li, T.; Zhao, X. Two-Level Optimal Scheduling Strategy of Electric Vehicle Charging Aggregator Based on Charging Urgency. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Smart Power & Internet Energy Systems (SPIES), Beijing, China, 9–12 December 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1755–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Rana, R.; Mishra, S. Multi Priority-Queuing algorithm for Real Time Charge Scheduling of Electric Vehicles on Highways based on Time allotment. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Smart Grid and Renewable Energy (PESGRE2020), Cochin, India, 2–4 January 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electrify America. Congestion Reduction Effort (State of Charge Pilot). Available online: https://www.electrifyamerica.com/soc-pilot/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Acharya, S.; Dvorkin, Y.; Karri, R. Causative Cyberattacks on Online Learning-Based Automated Demand Response Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3548–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangir, H.; Gougheri, S.S.; Vatandoust, B.; Golkar, M.A.; Golkar, M.A.; Ahmadian, A.; Hajizadeh, A. A Novel Cross-Case Electric Vehicle Demand Modeling Based on 3D Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangir, H.; Lakshminarayana, S.; Poor, H.V. Charge Manipulation Attacks Against Smart Electric Vehicle Charging Stations and Deep Learning-Based Detection Mechanisms. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 5182–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Du, C.; You, T.; Bai, L.; Wu, J. Dynamic Programming-Based Optimal Charging Scheduling for Electric Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 7th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Engineering (ICITE), Beijing, China, 11–13 November 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frendo, O.; Graf, J.; Gaertner, N.; Stuckenschmidt, H. Data-driven smart charging for heterogeneous electric vehicle fleets. Energy AI 2020, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecolo, R.; Khandoker, M.S.; Hossain, S.; Niloy, A.; Fahim, I.A.; Aziz, T. EV Charging Framework: Enhancing Urban Charging Infrastructure with SOC and Emergency Prioritization. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques (ICREST), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 11–12 January 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbal, A.; Alrifaie, M.F. A User-Preference-Based Charging Station Recommendation for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 11617–11634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikzad, M.; Samimi, A. Assessment of Time-Based Demand Response Programs for Electric Vehicle Charging Facilities. Renew. Energy Focus 2025, 53, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenmayr, U.; Wang, W.; Jochem, P. Unit commitment of photovoltaic-battery systems: An advanced approach considering uncertainties from load, electric vehicles, and photovoltaic. Appl. Energy 2020, 280, 115972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Gao, S.; Liu, Y.; Song, T.E.; Han, H. A model predictive control approach in microgrid considering multi-uncertainty of electric vehicles. Renew. Energy 2021, 163, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jochem, P.; Fichtner, W. A scenario-based stochastic optimization model for charging scheduling of electric vehicles under uncertainties of vehicle availability and charging demand. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 119886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniyappan, B.; Vinopraba, T. Dynamic pricing for load shifting: Reducing electric vehicle charging impacts on the grid through machine learning-based demand response. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, M.; Yang, Z.; Li, G. Coordinating Flexible Demand Response and Renewable Uncertainties for Scheduling of Community Integrated Energy Systems with an Electric Vehicle Charging Station: A Bi-Level Approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, 12, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Jiao, L.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, L. Scheduling Online EV Charging Demand Response via V2V Auctions and Local Generation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 11436–11452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.S.; Yong, J.Y.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Tan, K.M.; Mansor, M.; Tariq, M. Priority-based vehicle-to-grid scheduling for minimization of power grid load variance. J. Energy Storage 2021, 39, 102607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.; Iuliano, S.; Galdi, V.; Calderaro, V.; Graber, G. Achieving Consensus in Self-Organizing Electric Vehicles for Implementing V2G-Based Ancillary Services. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 137222–137236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Dominguez, D.; Ejeh, J.; Brown, S.F.; Dunbar, A.D. Exploring the possibility to provide black start services by using vehicle-to-grid. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.B.; Siraj, M.S.; Tsiropoulou, E.E.; Fragkos, G.; Sullivant, R.; Choe, Y.R.; Rhee, J.; Lee, K.H. Reevaluating Optional Fields in OCPP 2.0.1: Preliminary Case Study by Spoofing State of Charge. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 30th International Workshop on Computer Aided Modeling and Design of Communication Links and Networks (CAMAD), Tempe, AZ, USA, 14–16 October 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.S.; Sarker, M.T.; Nabi, M.S.; Bannah, H.; Ramasamy, G.; Eng Eng, N. Federated AI-OCPP Framework for Secure and Scalable EV Charging in Smart Cities. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO Standard 15118-2; Road Vehicles—Vehicle to Grid Communication Interface—Part 2: Network and Application Protocol Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Open Charge Alliance. OCPP 2.0.1—Part 2: Specification; Technical Report; Version 2.0.1—Revision Date: 15 December 2022; Open Charge Alliance: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scholkopf, B.; Smola, A.J. Learning with Kernels: Support Vector Machines, Regularization, Optimization, and Beyond; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi, R.; Khan, M.A.; Sorrentino, D.; Diaine, C.; Malekjafarian, A. An unsupervised anomaly detection framework for onboard monitoring of railway track geometrical defects using one-class support vector machine. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; McCann, R.A.; Huang, Y.; Wang, W.; Kong, J. Malware detection for internet of things using one-class classification. Sensors 2024, 24, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinon, N.; Trombetta, R.; Lartizien, C. One-Class SVM on siamese neural network latent space for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection on brain MRI White Matter Hyperintensities. Med. Imaging Deep. Learn. 2024, 227, 1783–1797. [Google Scholar]

- DESL-EPFL. Level 3 Electric Vehicle Charging Dataset. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/DESL-EPFL/Level-3-EV-charging-dataset (accessed on 31 May 2025).

| Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| DR | Demand Response |

| EDR | Emergency Demand Response |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| EVCS | Electric Vehicle Charging Station |

| EVSE | Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment |

| MITM | Man-in-the-Middle |

| OCPP | Open Charge Point Protocol |

| OCSVM | One-Class Support Vector Machine |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PKI | Public Key Infrastructure |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

| Model Configuration | F1-Score (%) | False Negatives | True Positives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without Engineered Features | 87 | 56 | 345 |

| With Engineered Features | 90 | 40 | 361 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rahman, A.B.; Siraj, M.S.; Tsiropoulou, E.E.; Fragkos, G.; Sullivant, R.; Choe, Y.R.; Jimenez, J.; Rhee, J.; Lee, K.H. Unsupervised Detection of SOC Spoofing in OCPP 2.0.1 EV Charging Communication Protocol Using One-Class SVM. Future Internet 2026, 18, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010060

Rahman AB, Siraj MS, Tsiropoulou EE, Fragkos G, Sullivant R, Choe YR, Jimenez J, Rhee J, Lee KH. Unsupervised Detection of SOC Spoofing in OCPP 2.0.1 EV Charging Communication Protocol Using One-Class SVM. Future Internet. 2026; 18(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahman, Aisha B., Md Sadman Siraj, Eirini Eleni Tsiropoulou, Georgios Fragkos, Ryan Sullivant, Yung Ryn Choe, Jhaell Jimenez, Junghwan Rhee, and Kyu Hyung Lee. 2026. "Unsupervised Detection of SOC Spoofing in OCPP 2.0.1 EV Charging Communication Protocol Using One-Class SVM" Future Internet 18, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010060

APA StyleRahman, A. B., Siraj, M. S., Tsiropoulou, E. E., Fragkos, G., Sullivant, R., Choe, Y. R., Jimenez, J., Rhee, J., & Lee, K. H. (2026). Unsupervised Detection of SOC Spoofing in OCPP 2.0.1 EV Charging Communication Protocol Using One-Class SVM. Future Internet, 18(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010060