Cross-Gen: An Efficient Generator Network for Adversarial Attacks on Cross-Modal Hashing Retrieval

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose Cross-Gen, an efficient parallel generator framework that rapidly learns the decision behavior of a target CMHR model and generates cross-modal adversarial examples at inference time without iterative optimization.

- We design a training strategy that acquires relevant cross-modal pairs via interaction with the target model and optimizes the generator using a composite objective combining adversarial, quantization, and reconstruction losses.

- We conduct comprehensive experiments on FLICKR-25K and NUS-WIDE with diverse model backbones, demonstrating that Cross-Gen outperforms iterative baselines in generation speed while maintaining strong attack efficacy.

2. Background

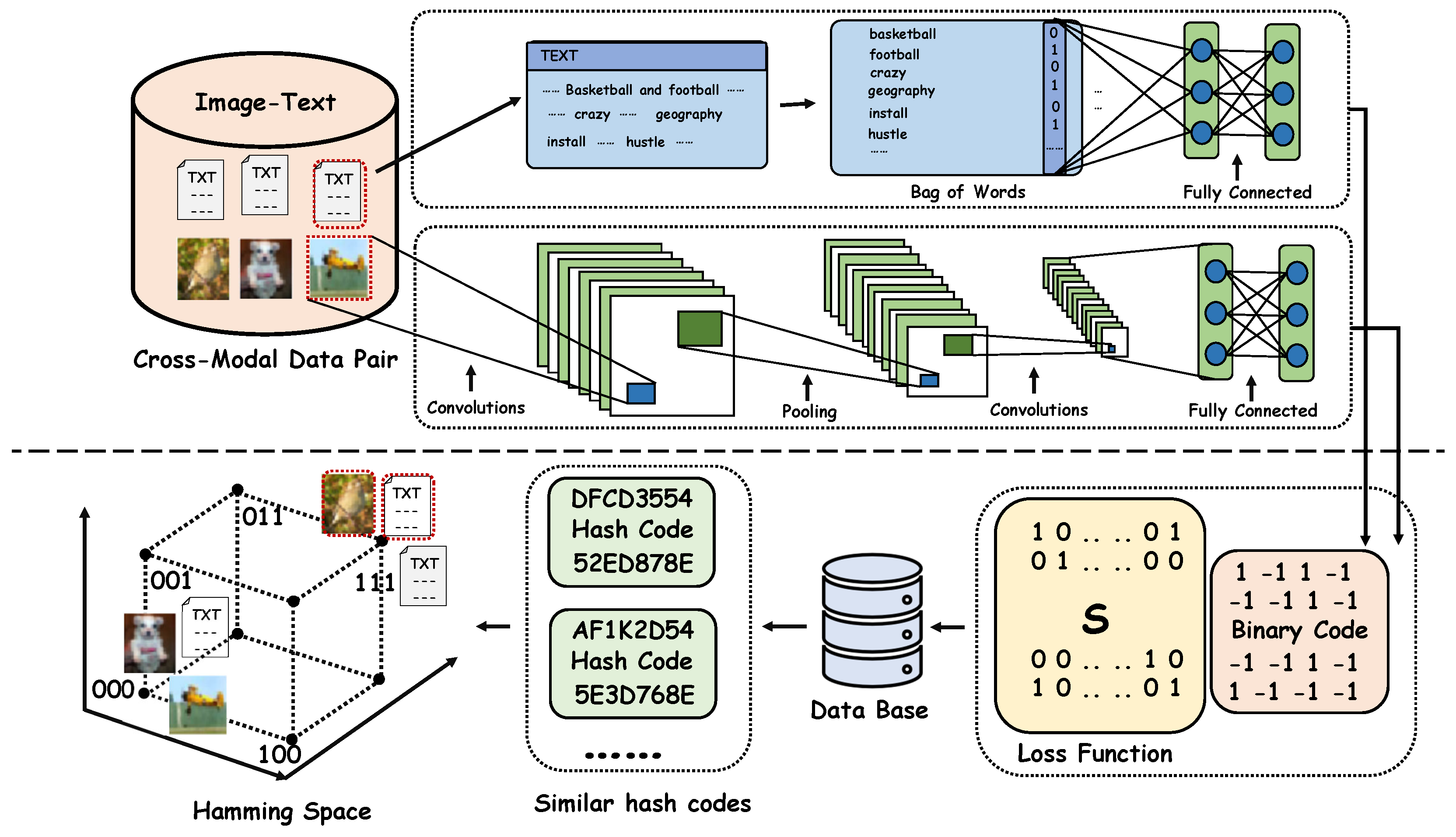

2.1. Cross-Modal Hash Retrieval System

- Embedding semantically aligned cross-modal data pairs into a joint vector space.

- Designing an optimization objective that enhances both semantic consistency and Hamming-space similarity between paired samples.

- Generating binary hash codes for all cross-modal data and storing them in a database to support efficient retrieval.

2.2. Problem Formulation

3. Framework

3.1. Overview

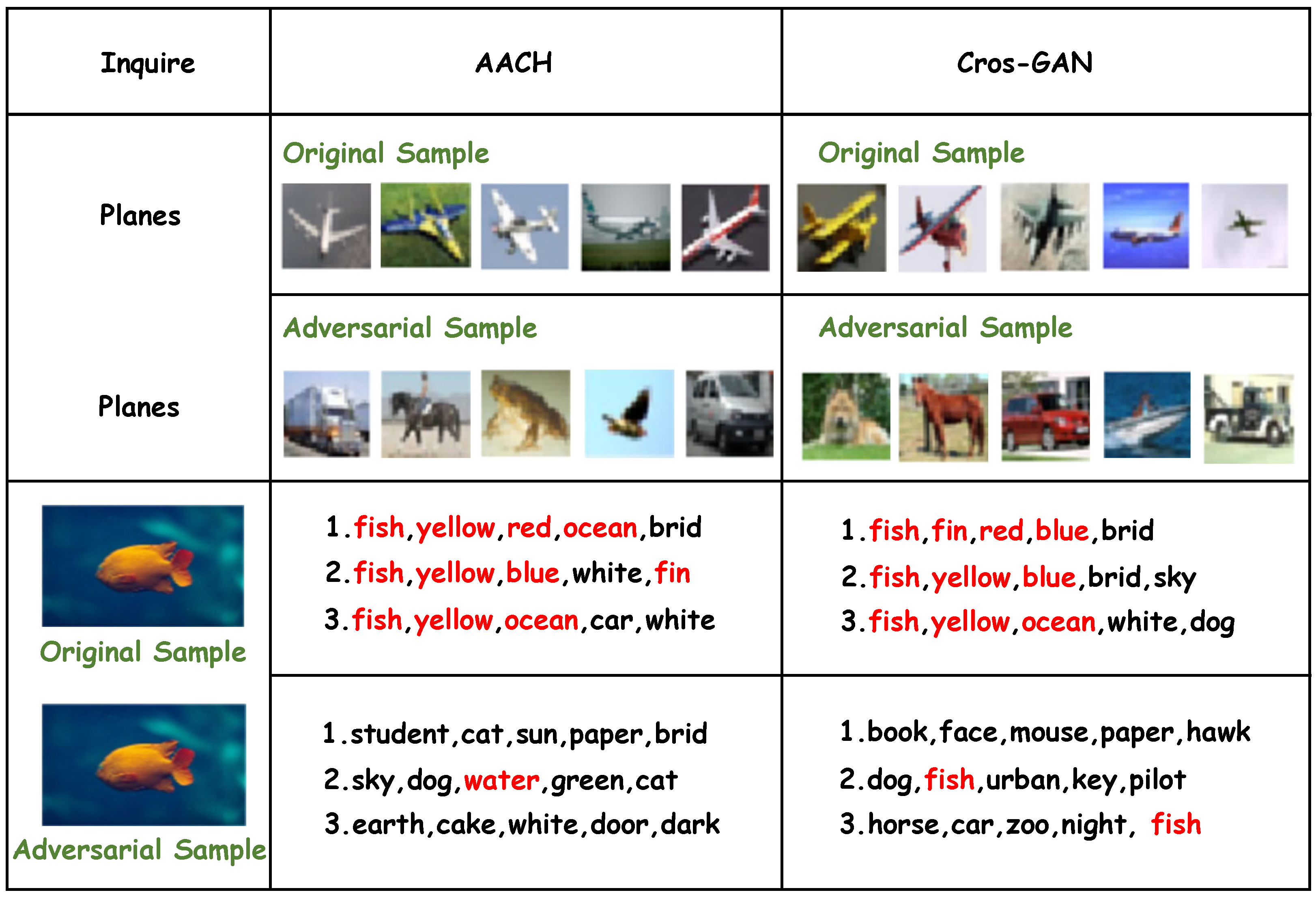

3.2. Cross-Modal Data Adversarial Generator

- Adversarial and original input data have significant Hamming distance.

- In the training process, the network needs to generate compact hash codes.

- The generated adversarial examples are invisible from the original input examples.

3.3. Implementation

- For the image-to-text task, we build the adversarial image generator using a modified AlexNet or ResNet-34/50. All backbones are initialized with ImageNet pre-trained weights, and the final classification layer is replaced by a deconvolutional head that outputs perturbed images of the same size as the input (e.g., ). The generator takes a clean image and produces an adversarial version , where the perturbation is constrained by to ensure visual imperceptibility.

- For the text-to-image task, we construct the adversarial text generator based on a 2-layer LSTM [38] with 512 hidden units per layer. The input is the original bag-of-words (BoW) vector, and the output is a perturbed textual representation in the same embedding space. Since text perturbations operate in the continuous feature domain, no explicit norm constraint is applied.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

- Statistical significance: 1000 samples provide sufficient diversity to cover multiple semantic categories while ensuring stable evaluation of attack success rate.

- Computational feasibility: Generating high-quality adversarial examples is resource-intensive, and 1000 queries represent a commonly adopted scale in recent adversarial cross-modal studies [36].

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Compared Method

4.4. Results

4.5. Running Time and Imperceptibility

5. Related Work

5.1. Deep Cross-Modal Hamming Retrieval

5.2. Adversarial Attacks on Deep Cross-Modal Hamming Retrieval

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hong, F.; Liu, C.; Yuan, X. DNN-VolVis: Interactive volume visualization supported by deep neural network. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Pacific Visualization Symposium (PacificVis), Bangkok, Thailand, 23–26 April 2019; pp. 282–291. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M.; Lippel, J.; Stuhlsatz, A.; Zielke, T. Robust dimensionality reduction for data visualization with deep neural networks. Graph. Model. 2020, 108, 101060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Long, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; Yu, P.S. Deep visual-semantic hashing for cross-modal retrieval. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1445–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.Y.; Li, W.J. Deep cross-modal hashing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3232–3240. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, B.; Long, M.; Wang, J. Cross-modal hamming hashing. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 202–218. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, S.; Han, Y. Curls & whey: Boosting black-box adversarial attacks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 6519–6527. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Gardner, J.; You, Y.; Wilson, A.G.; Weinberger, K. Simple black-box adversarial attacks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 2484–2493. [Google Scholar]

- Komkov, S.; Petiushko, A. Advhat: Real-world adversarial attack on arcface face id system. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 819–826. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6199. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.M.; Fawzi, A.; Frossard, P. Deepfool: A simple and accurate method to fool deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2574–2582. [Google Scholar]

- Dusmanu, M.; Schonberger, J.L.; Sinha, S.N.; Pollefeys, M. Privacy-preserving image features via adversarial affine subspace embeddings. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 14267–14277. [Google Scholar]

- Che, Z.; Borji, A.; Zhai, G.; Ling, S.; Guo, G.; Callet, P.L. Adversarial attacks against deep saliency models. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.01231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, A.; Engstrom, L.; Athalye, A.; Lin, J. Black-box adversarial attacks with limited queries and information. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 2137–2146. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagoji, A.N.; He, W.; Li, B.; Song, D. Practical black-box attacks on deep neural networks using efficient query mechanisms. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 154–169. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Jordan, M.I.; Wainwright, M.J. Hopskipjumpattack: A query-efficient decision-based attack. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (sp), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–20 May 2020; pp. 1277–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Li, B. Qeba: Query-efficient boundary-based blackbox attack. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1221–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Na, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, K.; Park, J.; Hwang, J.Y.; Choi, J.P. Domain adaptive transfer attack-based segmentation networks for building extraction from aerial images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 5171–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Pino, J.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Genzel, D. Improving speech translation by understanding and learning from the auxiliary text translation task. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.05782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Neupane, A.; Paul, S.; Song, C.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Roy-Chowdhury, A.K.; Swami, A. Stealthy Adversarial Perturbations Against Real-Time Video Classification Systems. In Proceedings of the NDSS’19, San Diego, CA, USA, 24–27 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, B.; Shen, F.; Lu, G. Prototype-supervised adversarial network for targeted attack of deep hashing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 16357–16366. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Tan, Y. Generating adversarial malware examples for black-box attacks based on GAN. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.05983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Huiskes, M.J.; Lew, M.S. The mir flickr retrieval evaluation. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Conference on Multimedia Information Retrieval, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30–31 October 2008; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, T.S.; Tang, J.; Hong, R.; Li, H.; Luo, Z.; Zheng, Y. Nus-wide: A real-world web image database from national university of singapore. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Image and Video Retrieval, Santorini, Greece, 8–10 July 2009; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Y.; Torralba, A.; Fergus, R. Spectral hashing. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2008, 21, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Pushpalatha., K.R.; Chaitra., M.; Karegowda, A.G. Color Histogram based Image Retrieval—A Survey. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci. 2013, 4, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, R.; Zhou, Z.H. Understanding bag-of-words model: A statistical framework. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2010, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Li, C.; Yan, J.; Deng, C.; Liu, X. Graph Convolutional Network Hashing for Cross-Modal Retrieval. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; Volume 2019, pp. 982–988. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Sebe, N.; Shen, H.T. A survey on learning to hash. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 769–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Lang, B.; Li, X. Large-scale unsupervised hashing with shared structure learning. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2014, 45, 1811–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Q.; Huang, L.; Wei, Z.; Xie, K.; Zhang, W. Unsupervised deep multi-similarity hashing with semantic structure for image retrieval. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 31, 2852–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Kitani, K.M. Deep supervised hashing with triplet labels. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 November 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, R.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. Deep supervised hashing for fast image retrieval. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2064–2072. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.; Xie, H.; Yang, D.; Yin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Q. Supervised hash coding with deep neural network for environment perception of intelligent vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 19, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, S.; Deng, C.; Liu, W.; Huang, H. Adversarial Attack on Deep Cross-Modal Hamming Retrieval. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2218–2227. [Google Scholar]

- Papernot, N.; McDaniel, P.; Goodfellow, I.; Jha, S.; Celik, Z.B.; Swami, A. Practical black-box attacks against machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2–6 April 2017; pp. 506–519. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, S.; Deng, C.; Xie, D.; Liu, W. Cross-modal learning with adversarial samples. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 10792–10802. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, C. Deep joint-semantics reconstructing hashing for large-scale unsupervised cross-modal retrieval. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3027–3035. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, S.; Oh, S.J.; De Rezende, R.S.; Kalantidis, Y.; Larlus, D. Probabilistic embeddings for cross-modal retrieval. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 8415–8424. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Tang, H.; Deng, C.; Zhan, L.; Liu, W. Vulnerability vs. reliability: Disentangled adversarial examples for cross-modal learning. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual Event, USA, 23–27 August 2020; pp. 421–429. [Google Scholar]

| Tasks | Method | Iteration | FLICKER-25k | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlexNet | ResNet-34 | ResNet-50 | |||

| I→T | Original | 74.40% | 80.24% | 79.78% | |

| AACH | 100 | 59.97% | 64.15% | 63.43% | |

| 500 | 58.60% | 63.02% | 62.98% | ||

| Ours | 1 | 56.21% | 60.58% | 60.24% | |

| T→I | Original | 71.87% | 77.58% | 76.81% | |

| AACH | 100 | 59.59% | 67.47% | 62.84% | |

| 500 | 58.64% | 66.68% | 61.80% | ||

| Ours | 1 | 57.83% | 65.93% | 60.50% | |

| Tasks | Method | Iteration | NUS-WIDE | ||

| AlexNet | ResNet-34 | ResNet-50 | |||

| I→T | Original | 56.25% | 66.04% | 65.97% | |

| AACH | 100 | 33.93% | 40.16% | 41.47% | |

| 500 | 33.52% | 39.94% | 40.52% | ||

| Ours | 1 | 30.13% | 36.92% | 39.43% | |

| T→I | Original | 54.08% | 56.95% | 59.14% | |

| AACH | 100 | 36.71% | 47.07% | 47.91% | |

| 500 | 36.55% | 46.37% | 46.73% | ||

| Ours | 1 | 34.33% | 43.26% | 45.58% | |

| Tasks | Method | Iteration | FLICKER-25k | Method | Iteration | NUS-WIDE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Per | Time | Per | |||||

| I→T | AACH | 100 | 0.31 | 1.14 | AACH | 100 | 0.34 | 1.28 |

| 500 | 1.27 | 0.93 | 500 | 1.44 | 1.19 | |||

| Ours | 1 | 0.011 | 1.95 | Ours | 1 | 0.006 | 1.77 | |

| T→I | AACH | 100 | 0.98 | 1.84 | AACH | 100 | 0.56 | 1.30 |

| 500 | 3.81 | 1.67 | 500 | 2.03 | 1.26 | |||

| Ours | 1 | 0.004 | 2.06 | Ours | 1 | 0.009 | 1.98 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, C.; Chen, L.; Li, S.; Yi, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Shi, R. Cross-Gen: An Efficient Generator Network for Adversarial Attacks on Cross-Modal Hashing Retrieval. Future Internet 2025, 17, 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120573

Hu C, Chen L, Li S, Yi Y, Zhan Y, Liu C, Liu J, Shi R. Cross-Gen: An Efficient Generator Network for Adversarial Attacks on Cross-Modal Hashing Retrieval. Future Internet. 2025; 17(12):573. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120573

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Chao, Li Chen, Sisheng Li, Yin Yi, Yu Zhan, Chengguang Liu, Jianling Liu, and Ronghua Shi. 2025. "Cross-Gen: An Efficient Generator Network for Adversarial Attacks on Cross-Modal Hashing Retrieval" Future Internet 17, no. 12: 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120573

APA StyleHu, C., Chen, L., Li, S., Yi, Y., Zhan, Y., Liu, C., Liu, J., & Shi, R. (2025). Cross-Gen: An Efficient Generator Network for Adversarial Attacks on Cross-Modal Hashing Retrieval. Future Internet, 17(12), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120573