STREAM: A Semantic Transformation and Real-Time Educational Adaptation Multimodal Framework in Personalized Virtual Classrooms

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Section 2: Survey of Enabling Technologies—A comprehensive review of existing AI tools and technologies relevant to content analysis, learner modeling, planned for real-time but tested offline, and multi-modal delivery. The section highlights current capabilities and identifies the limitations of existing systems, underscoring the need for the proposed STREAM framework.

- Section 3: STREAM Framework: Concepts, Architecture, Components—This section introduces the conceptual framework that outlines the end-to-end flow of content from instructional source to personalized delivery. It details the system’s key components, including content decomposition, learner profiling, and adaptive multi-modal presentation.

- Section 4: Feasibility and Early Prototype Design—This section presents the initial implementation strategy, including designing a pilot study using pre-recorded lectures. It outlines the methodological approach to analyzing content and simulating adaptive delivery based on the learners’ preferences.

- Section 5: Discussion—An analytical discussion of how STREAM addresses existing gaps in the literature. The section examines the theoretical and practical implications of implementing such a system, with a focus on potentially enhancing equity and responsiveness pending validation studies in virtual learning.

- Section 6: Conclusion and Next Steps—A summary of key contributions, followed by a roadmap for future research, including the development of subsequent papers that will explore specific components of the framework in depth.

2. Survey of Enabling Technologies

2.1. Content Analysis Tools, Intended for Real-Time

2.2. Learner Modeling and Preference Detection

2.3. Multimodal Delivery Tools

2.4. Existing Adaptive Learning Systems

2.5. UDL and Metadata-Driven Adaptation in Prior Research

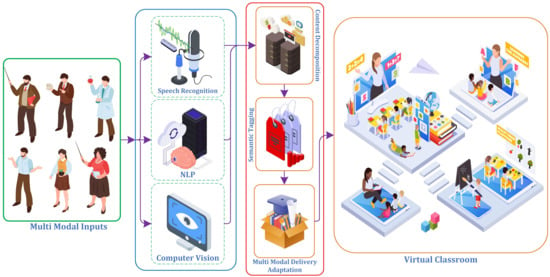

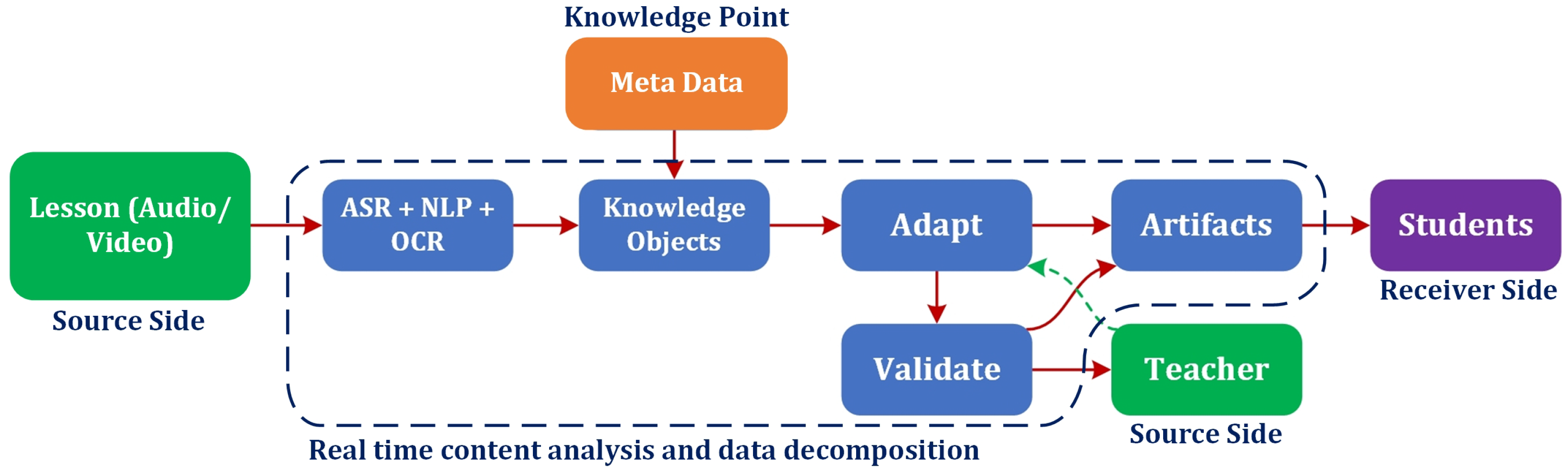

3. STREAM Framework: Concepts, Architecture, Components

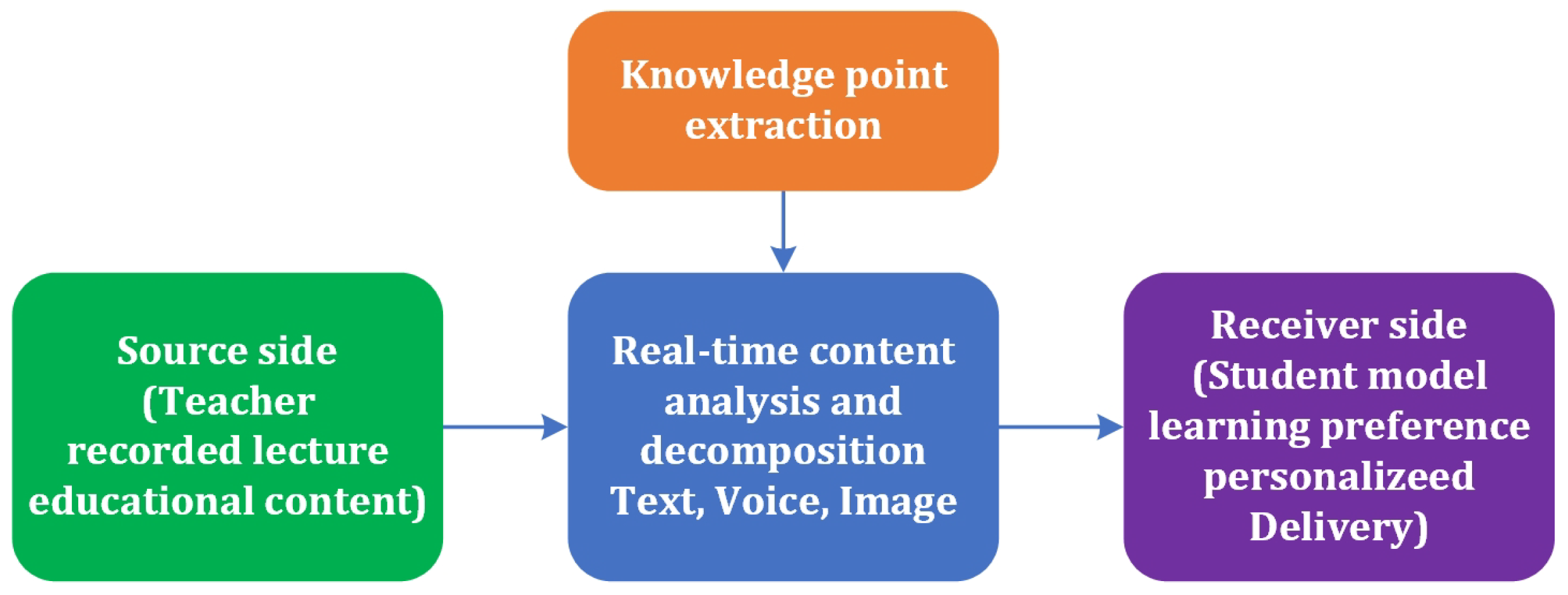

3.1. Conceptual Flow

3.1.1. Source Side

3.1.2. Middle Layer

3.1.3. Receiver Side

3.2. Key Components

3.2.1. Knowledge Point Extraction

3.2.2. Metadata Generation

3.2.3. Learner Profiling

3.2.4. Adaptive Content Generation

3.3. Modularity

4. Feasibility and Early Prototype Design

- (i)

- Knowledge Point Extraction—time-aligned ASR and transformer tagging produce machine-interpretable objects for definitions, step sequences, prompts, and entities;

- (ii)

- Metadata Generation—each object carries provenance and pedagogical fields (ID, timecodes, Bloom level, difficulty, prerequisites, visual references) to preserve auditability;

- (iii)

- Adaptive Content Delivery—rule-based mappings regenerate visual-first artifacts (arrow-sequence → numbered path diagram; prompt → two-panel Plan → Test; entity → pictogram with OCR caption);

- (iv)

- Learner Profiling—intentionally out of scope in this pilot (fixed visual profile) to isolate feasibility of the content–to–adaptation loop.

4.1. Pilot Implementation of Source Side: Pre-Recorded Lecture "Pree"

4.2. Middle Layer: Content Component Extraction

| S1 [00:02:10.00-00:02:15.00]: |

| ″From the start, go forward, forward, then right to reach the zoo.″ |

| S2 [00:02:15.10-00:02:16.80]: |

| ″Show me the path.″ |

| S3 [00:02:17.00-00:02:18.50]: |

| ″Test it with your car.″ |

| Sentence segmentation (spaCy) |

| [ S1 | S2 | S3 ] |

| Multi-label classifier outputs (BERT + sigmoid) |

| # probs shown only for labels ≥ 0.05 |

| S1: |

| knowledge_point: 0.88 |

| entity: 0.11 (token "zoo") |

| example: 0.07 |

| S2: |

| prompt: 0.95 |

| S3: |

| prompt: 0.93 |

| Rule-assisted passes |

| Imperative detector: |

| S2 → prompt=True (verb-initial "Show") |

| S3 → prompt=True (verb-initial "Test") |

| Arrow-sequence parser (token collapse): |

| S1 evidence span chars [16,47) = "go forward, forward, then right" |

| canonical_steps: ["forward","forward","right"] |

| Exported tag items (JSON Lines) |

| "sentence_id":"S1", |

| "time":{"start":"00:02:10.00","end":"00:02:15.00"}, |

| "text":"From the start, go forward, forward, then right to reach the zoo.", |

| "labels":{"knowledge_point":0.88,"entity":0.11,"example":0.07}, |

| "evidence_spans":{"steps":[16,47]}, |

| "canonical_steps":["forward","forward","right"] |

| "sentence_id":"S2", |

| "time":{"start":"00:02:15.10","end":"00:02:16.80"}, |

| "text":"Show me the path.", |

| "labels":{"prompt":0.95}, |

| "evidence_spans":{"prompt":[66,83]} |

| "sentence_id":"S3", |

| "time":{"start":"00:02:17.00","end":"00:02:18.50"}, |

| "text":"Test it with your car.", |

| "labels":{"prompt":0.93}, |

| "evidence_spans":{"prompt":[84,106]} |

- "id",

- "timecodes",

- "text",

- "visual_refs",

- "type" {definition, step, prompt, example},

- "bloom_level",

- "difficulty",

- "prerequisites"

| "id": "KO-0142", |

| "timecodes": {"start": "00:02:11.20", "end": "00:02:14.90"}, |

| "text": "forward, forward, right", |

| "type": "step", |

| "asr_conf": 0.93, |

| "tag_conf_map": {"knowledge_point": 0.88}, |

| "visual_refs": [{"frame": 3187, "bbox": [412, 276, 86, 44], "ocr": null}], |

| "bloom_level": "apply", |

| "difficulty": "intro", |

| "prerequisites": ["KO-0061: forward arrow meaning"], |

| "source_hash": "c7a9f2" |

4.3. Receiver Side: Single Student Style Adaptation

4.4. Content Decomposition and Prompt Generation

4.5. Tools

4.6. Feasibility Criteria & Quick Evaluation

4.7. Scope

4.8. Risks & Immediate Mitigations

4.9. Pilot Study Outcomes

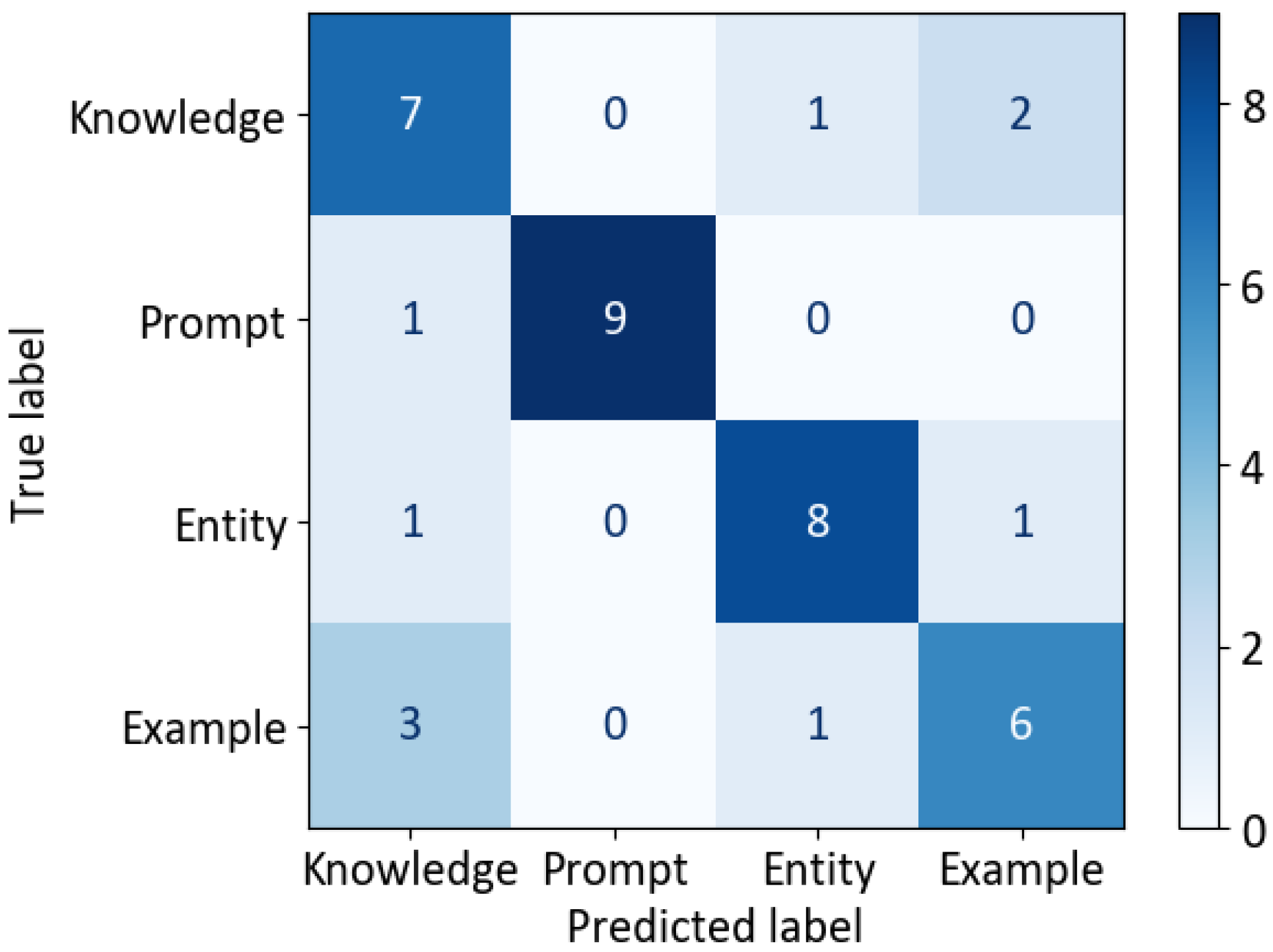

4.9.1. Accuracy

4.9.2. Latency and Resources

4.9.3. Output Quality

4.9.4. Traceability and Provenance

4.9.5. Lightweight Ablations

5. Discussion

5.1. Why STREAM Is Designed to Fill an Important Research Gap?

5.2. Intended Alignment with Personalized Learning Theories

5.3. Potential Role of AI in Equity and Access

5.4. Potential for Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

5.5. Limitations and Roadmap for Validation

- Phase 1: Expanded content testing (short-term, 3–6 months): Apply the STREAM framework to a corpus of 20–30 lessons (5–15 min each) spanning STEM, humanities, and languages. Include varied input qualities (e.g., noisy audio from actual classrooms, handwritten slides, multilingual content). Metrics: ASR accuracy (>85%), tagging fidelity (inter-rater agreement >0.8 via human annotation), latency (<5 s end-to-end). This will test robustness to content diversity.

- Phase 2: Multi-profile learner validation (medium-term, 6–12 months): Conduct user studies with 50–100 diverse participants (e.g., multilingual learners, students with disabilities like dyslexia or ADHD, varying ages/levels). Simulate profiles beyond the visual (e.g., auditory, kinesthetic) and measure outcomes such as comprehension retention (using pre- and post-tests), engagement (measured by time-on-task and self-reported via surveys), and preference matching. Use A/B testing to compare adapted vs. non-adapted content. This will evaluate equity impacts in controlled lab settings.

- Phase 3: Real-world deployment pilots (long-term, 12–24 months): Deploy in 3–5 virtual classrooms (e.g., K-12 and higher ed, urban/rural sites) with bandwidth constraints. Integrate with platforms like Zoom or Moodle, tracking scalability metrics (e.g., concurrent users without latency spikes, edge vs. cloud performance). Include ethical reviews for privacy and bias audits. Longitudinal data will assess sustained potential impacts on accessibility pending validation.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Contribution Summary

6.2. Scope Alignment

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CV | Computer Vision |

| fps | frames per second |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| NER | Named Entity Recognition |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PNG | Portable Network Graphics |

| SER | Sentence Error Rate |

| STREAM | Semantic Transformation and Real-Time Educational Adaptation Multimodal |

| SVG | Scalable Vector Graphics |

| T5 | Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer |

| TTS | Text-to-Speech |

| UDL | Universal Design for Learning |

| VAD | Voice Activity Detection |

| VARK | Visual, Auditory, Reading/Writing, Kinesthetic |

| VLEs | Virtual Learning Environments |

| VRAM | Video Random-Access Memory |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| WCAG | Web Content Accessibility Guidelines |

| WER | Word Error Rate |

References

- Spaho, E.; Çiço, B.; Shabani, I. IoT Integration Approaches into Personalized Online Learning: Systematic Review. Computers 2025, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, I.A.; Burbules, N.C. Online education viewed through an equity lens: Promoting engagement and success for all learners. Rev. Educ. 2022, 10, e3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.H.; Meyer, A. Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning; ERIC; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T.E.; Meyer, A.; Rose, D.H. Universal Design for Learning in the Classroom: Practical Applications; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, H.; Hussain, M.A.; Tufail, M. Effect of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Embedded Project on 5th Grade Students’ Academic Achievement in Science Subject. Bull. Educ. Res. 2024, 46, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Altowairiki, N.F. Universal Design for Learning Infusion in Online Higher Education. Online Learn. 2023, 27, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Bashir, S.; Rana, K.; Lambert, P.; Vernallis, A. Post-COVID-19 adaptations; the shifts towards online learning, hybrid course delivery and the implications for biosciences courses in the higher education setting. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 711619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xu, W.; Yu, L. Constructing an online sustainable educational model in COVID-19 pandemic environments. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Bhatia, P.; Murphy, M.; Pereira, A.L. Digital education colonized by design: Curriculum reimagined. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Grebennikova, V.; Lisovskiy, A.; Rakhimova, G.; Vasileva, T. AI-driven adaptive learning for sustainable educational transformation. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 1921–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, S.; Li, J. A Review of Multimodal Interaction in Remote Education: Technologies, Applications, and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, O.O.; Al Hamad, N.M.; Chisom, O.N.; Osawaru, B.; Adewusi, O.E. AI in education: A review of personalized learning and educational technology. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 18, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.S.; Renumol, V. A systematic literature review on adaptive content recommenders in personalized learning environments from 2015 to 2020. J. Comput. Educ. 2022, 9, 113–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, M.S. Using AI for adaptive learning and adaptive assessment. In Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Machine-Generated Literature Overview; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 341–466. [Google Scholar]

- Kabudi, T.; Pappas, I.; Olsen, D.H. AI-enabled adaptive learning systems: A systematic mapping of the literature. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M.T.; Qtaish, A. Effective Adaptive E-Learning Systems According to Learning Style and Knowledge Level. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2019, 18, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, H.R.; Hanirex, D.K. A deep learning-enabled approach for real-time monitoring of learner activities in adaptive e-learning environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Circuit Power and Computing Technologies (ICCPCT), Kollam, India, 8–9 August 2024; Volume 1, pp. 846–851. [Google Scholar]

- Aladakatti, S.S.; Senthil Kumar, S. Exploring natural language processing techniques to extract semantics from unstructured dataset which will aid in effective semantic interlinking. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 2023, 14, 2243004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passi, N.; Raj, M.; Shelke, N.A. A review on transformer models: Applications, taxonomies, open issues and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON), Pimari Chinchwad, India, 23–25 August 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zeeshan, R.; Bogue, J.; Asghar, M.N. Relative applicability of diverse automatic speech recognition platforms for transcription of psychiatric treatment sessions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 117343–117354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uke, S.; Junghare, P.; Kenjale, S.; Korade, S.; Kothwade, A. Comprehensive Real-Time Intrusion Detection System Using IoT, Computer Vision (OpenCV), and Machine Learning (YOLO) Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Intelligent Information Systems (ICUIS), Gobichettipalayam, India, 12–13 December 2024; pp. 1680–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Huang, R.T.; Sommer, M.; Pei, B.; Shidfar, P.; Rehman, M.S.; Ritzhaupt, A.D.; Martin, F. The efficacy of artificial intelligence-enabled adaptive learning systems from 2010 to 2022 on learner outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2024, 62, 1348–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, A.; Zhang, Y. Lwcnet: A lightweight and efficient algorithm for household waste detection and classification based on deep learning. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Asghar, M.R. Characterisation and quantification of user privacy: Key challenges, regulations, and future directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 27, 3266–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Dai, L.; Zheng, X. Advances in Wearable Sensors for Learning Analytics: Trends, Challenges, and Prospects. Sensors 2025, 25, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villegas-Ch, W.; Gutierrez, R.; Mera-Navarrete, A. Multimodal Emotional Detection System for Virtual Educational Environments: Integration Into Microsoft Teams to Improve Student Engagement. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 42910–42933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, J.; Pai, A.P.; Ishimaru, S. Toward an interactive reading experience: Deep learning insights and visual narratives of engagement and emotion. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 6001–6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lai, Y.; Huang, X. Innovations in Online Learning Analytics: A Review of Recent Research and Emerging Trends. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 166761–166775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaugg, T. Future innovations for assistive technology and universal design for learning. In Assistive Technology and Universal Design for Learning: Toolkits for Inclusive Instruction; Plural Publishing: San Diego, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 275–318. [Google Scholar]

- Kohnke, S.; Zaugg, T. Artificial intelligence: An untapped opportunity for equity and access in STEM education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraghmi, E.; Atwe, L.; Jaber, A. A Comparative Study of PEGASUS, BART, and T5 for Text Summarization Across Diverse Datasets. Future Internet 2025, 17, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orynbay, L.; Razakhova, B.; Peer, P.; Meden, B.; Emeršič, Ž. Recent advances in synthesis and interaction of speech, text, and vision. Electronics 2024, 13, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratschke, B.M. Generative AI and Education: Digital Pedagogies, Teaching Innovation and Learning Design; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, P.A.; Juanico, J.F. The Effectiveness of Khan Academy in Teaching Elementary Math. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BANU, J.S.; Preethi, G. Empowering Sentiment Analysis of Coursera Course Reviews with Sophisticated Artificial Bee Colony-Inspired Deep Q-Networks (SABC-DQN). J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2024, 102, 2338–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Tang, Y. AI-Driven Adaptive Learning and Management System Research: A Practical Framework Based on the ALEKS System. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Digital Ethics (ICAIDE), Guangzhou, China, 29–31 May 2025; pp. 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi, I.; Bose, C.; Tripathi, N. Transforming Education: Adaptive Learning, AI, and Online Platforms for Personalization. In Technology for Societal Transformation: Exploring the Intersection of Information Technology and Societal Development; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. Online Learning Platform of Modern Chinese Course Based on Multimodal Emotion-Aware Adaptive Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 3rd International Conference on Data Science and Network Security (ICDSNS), Tiptur, India, 25–26 July 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yeganeh, L.N.; Fenty, N.S.; Chen, Y.; Simpson, A.; Hatami, M. The future of education: A multi-layered metaverse classroom model for immersive and inclusive learning. Future Internet 2025, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, L.N.; Simpson, A.; Fenty, N.; Hatami, M.; Rho, S.; Park, S.; Chen, Y. Immersive Future: A Case Study of Metaverse in Preparing Students for Career Readiness. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking and Applications (MetaCom), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–29 August 2025; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bollu, J.; Relangi, S.R.S.P.; Musuku, S.; Gangadhar, P.; Divya Sri, K.S.; Sree, K.B. Personalized Learning Content Generator: A Multimodal Application with Ai-Driven Content Creation and Adaptive Learning. 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5221494 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Polonetsky, J.; Tene, O. Who is reading whom now: Privacy in education from books to MOOCs. Vanderbilt J. Entertain. Technol. Law 2014, 17, 927. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Kiriti, M.; Singh, H.; Shrivastava, A. Education AI: Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on education in the digital age. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2025, 16, 1424–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronseth, S.L.; Stefaniak, J.E.; Dalton, E.M. Maturation of Universal Design for Learning. Theories to Influence the Future of Learning Design and Technology: Theory Spotlight Competition 2021; EdTech Books: Provo, UT, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rappolt-Schlichtmann, G.; Daley, S.G.; Rose, L.T. A Research Reader “in” Universal Design for Learning; ERIC; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Utami, I.S. Universal Design for Learning in Online Education: A Systematic Review of Evidence-Based Practice for Supporting Students with Disabilities. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2025, 24, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.P.; Snow, K. Supporting students with diverse learning needs using universal design for learning in online learning: Voice of the students. J. Teach. Learn. 2024, 18, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadimas, D.; Kasapakis, V.; Kotis, K. A systematic review on the combination of VR, IoT and AI technologies, and their integration in applications. Future Internet 2025, 17, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, E.; Mohammad, F.; Stevens, L.; Burbelo, H.; Awoke, A.; Rewkowski, N.; Manocha, D. An overview of enhancing distance learning through emerging augmented and virtual reality technologies. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2023, 30, 4480–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höffler, T.N.; Leutner, D. Instructional animation versus static pictures: A meta-analysis. Learn. Instr. 2007, 17, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, P.; Marcus, N.; Chan, C.; Qian, N. Learning hand manipulative tasks: When instructional animations are superior to equivalent static representations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayi, E.A. Transitioning to blended learning during COVID-19: Exploring instructors and adult learners’ experiences in three Ghanaian universities. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 2760–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C. Meaning Particles and Waves in MOOC Video Lectures: A transpositional grammar guided observational analysis. Comput. Educ. 2025, 236, 105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chai, M.H.; Lin, P.H. Exploring the Impact of Interactive Multimedia E-Books on the Effectiveness of Environmental Learning, Pro-Environmental Attitudes, and Behavioural Intentions Among Primary School Students. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2025, 41, e70087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. Methodological and technological advancements in E-learning. Information 2025, 16, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgun, S.; Greenhow, C. Artificial intelligence in education: Addressing ethical challenges in K-12 settings. AI Ethics 2022, 2, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.; Smart, A.; Birhane, A. The reanimation of pseudoscience in machine learning and its ethical repercussions. Patterns 2024, 5, 101027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wang, H.; Song, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, J.; Pei, Y. A comprehensive review on synergy of multi-modal data and ai technologies in medical diagnosis. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Moon, J.; Eom, T.; Awoyemi, I.D.; Hwang, J. Generative AI-Enhanced Virtual Reality Simulation for Pre-Service Teacher Education: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Usability and Instructional Utility for Course Integration. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiaan, M.A.K.; Mukta, M.S.H.; Fatema, K.; Fahad, N.M.; Sakib, S.; Mim, M.M.J.; Ahmad, J.; Ali, M.E.; Azam, S. A review on large language models: Architectures, applications, taxonomies, open issues and challenges. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26839–26874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, C.N.; Tan, C.W.; Yu, P.D. MCQGen: A large language model-driven MCQ generator for personalized learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 102261–102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khonde, K.R.; Shah, J.; Patel, P. EchoSense AI Transcrib Using DevOps. In Proceedings of the 2024 Parul International Conference on Engineering and Technology (PICET), Vadodara, India, 3–4 May 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Almusfar, L.A. Improving learning management system performance: A comprehensive approach to engagement, trust, and adaptive learning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 46408–46425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.Y.; Kang, S.; Kim, S. A non-verbal teaching behaviour analysis for improving pointing out gestures: The case of asynchronous video lecture analysis using deep learning. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2024, 40, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, D. Intelligent analysis system for teaching and learning cognitive engagement based on computer vision in an immersive virtual reality environment. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Data player: Automatic generation of data videos with narration-animation interplay. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2023, 30, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, R.; Aslam, M. A Multi-Faceted Deep Learning Approach for Student Engagement Insights and Adaptive Content Recommendations. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 69236–69256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yu, D. Towards intelligent E-learning systems. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 7845–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwadei, A.M.; Mohsen, M.A. Investigation of the use of infographics to aid second language vocabulary learning. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Adams, C.B. Drawing from and expanding their toolboxes: Preschool teachers’ traditional strategies, unconventional opportunities, and novel challenges in scaffolding young children’s social and emotional learning during remote instruction amidst COVID-19. Early Child. Educ. J. 2023, 51, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reales, D.; Manrique, R.; Grévisse, C. Core Concept Identification in Educational Resources via Knowledge Graphs and Large Language Models. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Zhang, Y.W.; Xin, X.Q.; Cai, L.W. Sustainable personalized E-learning through integrated cross-course learning path planning. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridell, K.; Walldén, R. Graphical models for narrative texts: Reflecting and reshaping curriculum demands for Swedish primary school. Linguist. Educ. 2023, 73, 101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, H.; Vogel, B.; Jacobsson, A. Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches in digital education: A systematic revision. Information 2022, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, H. A convolutional recurrent neural-network-based machine learning for scene text recognition application. Symmetry 2023, 15, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Q.; Hodges, T.S.; Mousavi, V. Designing Writers: A Self-Regulated Approach to Multimodal Composition in Teacher Preparation and Early Grades. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.L.; Qin, J. Metadata; American Library Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Das Mandal, S.K.; Basu, A. Classification of action verbs of Bloom’s taxonomy cognitive domain: An empirical study. J. Educ. 2022, 202, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Sha, L.; Zeng, Z.; Gašević, D.; Liu, Z. Annotation Guideline-Based Knowledge Augmentation: Towards Enhancing Large Language Models for Educational Text Classification. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2025, 18, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J. Examining the characteristics of practical knowledge from four public Facebook communities of practice in instructional design and technology. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 90669–90689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sümer, Ö.; Goldberg, P.; D’Mello, S.; Gerjets, P.; Trautwein, U.; Kasneci, E. Multimodal engagement analysis from facial videos in the classroom. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021, 14, 1012–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, H. Integrating Emotion Recognition in Educational Robots Through Deep Learning-Based Computer Vision and NLP Techniques. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393945666 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Saxer, K.; Tuominen, H.; Schnell, J.; Mori, J.; Niemivirta, M. Lower Secondary Students’ Well-Being Profiles: Stability, Transitions, and Connections with Teacher–Student, and Student–Student Relationships. Child Youth Care Forum 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Cultura, S.; Sharma, K.; Giannakos, M.N. Multimodal teacher dashboards: Challenges and opportunities of enhancing teacher insights through a case study. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2023, 17, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fu, R.; Amin, M.B.; Kang, B. The impact of modern ai in metadata management. Hum.-Centric Intell. Syst. 2025, 5, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosha, N.F.; Ngulube, P. Metadata standard for continuous preservation, discovery, and reuse of research data in repositories by higher education institutions: A systematic review. Information 2023, 14, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, S.G.; Celik, T.; Human-Hendricks, N.E. Personalized adaptive learning technologies based on machine learning techniques to identify learning styles: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 48392–48409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Migut, G.; Specht, M. What attention regulation behaviors tell us about learners in e-reading?: Adaptive data-driven persona development and application based on unsupervised learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 118890–118906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Yu, L.; Asim, M.; Ahmed, A.; Wani, M.A. Enhancing e-learning adaptability with automated learning style identification and sentiment analysis: A hybrid deep learning approach for smart education. Information 2024, 15, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Chiu, C.N.; Wang, P.T.; Fang, L.D. VisFactory: Adaptive Multimodal Digital Twin with Integrated Visual-Haptic-Auditory Analytics for Industry 4.0 Engineering Education. Multimedia 2025, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S.A.; Alomari, K.M.; Alfaisal, A.M.; Aljanada, R.A.; Basiouni, A. Emotion recognition for enhanced learning: Using AI to detect students’ emotions and adjust teaching methods. Smart Learn. Environ. 2025, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Maazouzi, Q.; Retbi, A. Multimodal Detection of Emotional and Cognitive States in E-Learning Through Deep Fusion of Visual and Textual Data with NLP. Computers 2025, 14, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troussas, C.; Krouska, A.; Sgouropoulou, C. Learner Modeling and Analysis. In Human-Computer Interaction and Augmented Intelligence: The Paradigm of Interactive Machine Learning in Educational Software; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 305–345. [Google Scholar]

- Sajja, R.; Sermet, Y.; Cikmaz, M.; Cwiertny, D.; Demir, I. Artificial intelligence-enabled intelligent assistant for personalized and adaptive learning in higher education. Information 2024, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorea, I.; Cioca, M.; Oancea, R.; Gorski, A.T.; Gorski, H.; Tudorache, P. Adaptive learning using artificial intelligence in e-learning: A literature review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliska, D.; Gudoniene, D. Sustainable technology-enhanced learning for learners with dyslexia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, T.; Babály, B.; Pataiová, H.; Kárpáti, A. Development of spatial abilities of preadolescents: What works? Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gm, D.; Goudar, R.; Kulkarni, A.A.; Rathod, V.N.; Hukkeri, G.S. A digital recommendation system for personalized learning to enhance online education: A review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 34019–34041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Online university teaching during and after the COVID-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigit. Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, S.; Daniel, S.; Haque, R.; Belkina, M.; Hassan, G.M.; Grundy, S.; Lyden, S.; Neal, P.; Sandison, C. ChatGPT versus engineering education assessment: A multidisciplinary and multi-institutional benchmarking and analysis of this generative artificial intelligence tool to investigate assessment integrity. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2023, 48, 559–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.; Uckelmann, D. Multi-Modal LA in Personalized Education Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 54049–54065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabane, L.; Ma, J.; Chu, R.; Cheng, J.; Ismaila, A.; Rios, L.P.; Robson, R.; Thabane, M.; Giangregorio, L.; Goldsmith, C.H. A tutorial on pilot studies: The what, why and how. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, G.A.; Dodd, S.; Williamson, P.R. Design and analysis of pilot studies: Recommendations for good practice. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2004, 10, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.G.; Carter, R.E.; Nietert, P.J.; Stewart, P.W. Recommendations for planning pilot studies in clinical and translational research. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2011, 4, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. bmj 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeqdad, Q.I.; Alodat, A.M.; Alquraan, M.F.; Mohaidat, M.A.; Al-Makhzoomy, A.K. The effectiveness of universal design for learning: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2218191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catama, B.V. Universal Design for Learning in Action: Exploring Strategies, Outcomes, and Challenges in Inclusive Education. Int. J. Rehabil. Spec. Educ. 2025, 5, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Campos, C. The impact of artificial intelligence on personalized learning in higher education: A systematic review. Trends High. Educ. 2025, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plooy, E.; Casteleijn, D.; Franzsen, D. Personalized adaptive learning in higher education: A scoping review of key characteristics and impact on academic performance and engagement. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thesen, T.; Park, S.H. A generative AI teaching assistant for personalized learning in medical education. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tolosa, L.; Rivas-Echeverria, F.; Marquez, R. Integrating AI in education: Navigating UNESCO global guidelines, emerging trends, and its intersection with sustainable development goals. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, C.; Lipuma, J.; Oviedo-Torres, X. Artificial intelligence in STEM education: A transdisciplinary framework for engagement and innovation. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1619888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, Z.; Paul, R.; Rahman, M.A.; Barua, T. A Systematic Review Of Human-AI Collaboration In It Support Services: Enhancing User Experience And Workflow Automation. J. Sustain. Dev. Policy 2025, 1, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I.; Bularca, A.R. Artificial Intelligence Governance in Higher Education: The Role of Knowledge-Based Strategies in Fostering Legal Awareness and Ethical Artificial Intelligence Literacy. Societies 2025, 15, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamad, S.; Chin, Y.H.; Zulmuksah, N.I.N.; Haque, M.M.; Shaheen, M.; Nisar, K. Technical review: Architecting an AI-driven decision support system for enhanced online learning and assessment. Future Internet 2025, 17, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasolla, F.; Zullo, A.; Maniglio, R.; Passaro, A.; Di Gioia, M.; Curcio, E.; Martini, E. Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning for Assessing and Enhancing Academic Performance in University Students: A Scoping Review. AI 2025, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Technology/Platform | Function | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| T5, BERT, GPT | Text-based content analysis and semantic extraction | Requires fine-tuning for educational contexts | |

| Content Analysis Tools, Designed for Real-Time but Offline-Tested | Whisper, Google Speech-to-Text | Speech recognition, and lecture transcription | Accuracy may drop with noisy inputs or accents |

| OpenCV, YOLO, Vision API | Visual content segmentation and object recognition | Limited interpretation of abstract visuals | |

| Emotion APIs, Affective Computing Tools | Detects emotional and motivational states in learners | Potential bias; limited granularity without hardware | |

| Learner Modeling & Preference Detection | Eye-tracking (Tobii, iMotions) | Tracks gaze, attention, and behavioral interaction | Intrusive or costly; sensitive to setup |

| VARK, Felder-Silverman Models | Categorizes learners by preferred learning modalities | Contested theoretical validity | |

| TTS Engines (Polly, WaveNet) | Delivers content in natural spoken formats | Modality fidelity varies by language and platform | |

| Multimodal Delivery Tools | ChatGPT, Gemini, GenAI | Generates custom content for adaptive instruction | Limited control over depth and granularity |

| Semantic Communication Models | Optimizes message meaning in low-bandwidth settings | Still emerging; high technical complexity | |

| Existing Adaptive Learning Systems | Khan Academy, Coursera, Smart Sparrow | Personalized paths based on performance history | Lacks adaptation and multimodal personalization, with real-time untested |

| Feature | STREAM | Khan Academy | Coursera | Smart Sparrow | Duolingo | ALEKS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation, Intended for Real-Time but Offline-Tested | Yes: Decomposes and adapts content during live/streamed lessons with <1 s latency on standard hardware. | Partial: AI feedback via Khanmigo; adapts between exercises from post-performance data; limited in-lesson processing. | Partial: Recommends modules post-quiz; no live decomposition/ regeneration. | Partial: Adaptive simulations, but rule-based and not designed for all content types in the offline-tested adaptation. | Partial: Adjusts difficulty in-session, but limited to gamified drills without full content transformation. | No: Adapts paths based on assessments; offline processing dominates. |

| Multimodal Content Delivery | Yes: Dynamically generates/regenerates across text, audio, video, diagrams; fuses ASR/NLP/CV for seamless integration. | Partial: Text, video, exercises with some AI narration; no modality switching or generation in the offline evaluation. | Partial: Video lectures, quizzes, text; limited to pre-made formats without fusion. | Yes: Interactive simulations with text/video; not AI-driven regeneration for live contexts. | Partial: Audio/text drills, images; app-based, no video decomposition or custom generation. | No: Primarily text-based math problems; minimal multimodal support. |

| Personalization Depth | High: Dynamic learner profiles (cognitive/affective states via eye-tracking, emotion APIs); adapts to preferences, disabilities, multilingual needs with UDL compatibility. | Medium: Performance-based paths with AI tutoring; basic mastery tracking, limited affective or behavioral modeling, with real-time untested. | Medium: Skill-based recommendations; learner profiles limited to progress/history. | High: Scenario-based adaptation; includes some behavioral cues, but not deeply affective. | Medium: Skill/decay models; gamified, but no deep affective or disability-focused profiles. | High: Knowledge-space theory for math; detailed but domain-specific; no multimodal/affective. |

| Content Decomposition & Tagging | Yes: AI-driven (BERT/T5 for semantics, Whisper for speech, YOLO/OpenCV for visuals); tags units with metadata for traceability. | No: Relies on pre-tagged content; no automated decomposition. | No: Courses are pre-structured; no tagging in the offline-tested system. | Partial: Tags simulations; manual/author-driven, not AI-automated. | No: Pre-built lessons; algorithmic but not decomposed via multimodal AI. | No: Pre-defined knowledge points; no multi-modal tagging, as real-time was not evaluated. |

| Equity & Accessibility Focus | High: Designed for diverse populations; supports multilingual use and disabilities via regenerated formats and provenance links. | Medium: Free access, subtitles, AI for underserved areas; largely one-size-fits-all. | Medium: Subtitles, mobile access; partnerships for equity, but not adaptive regeneration. | Medium: Customizable for inclusivity; deployment-limited. | High: Multilingual support, gamification for potential engagement pending validation; app-centric, less for disabilities. | Medium: Adaptive pacing; limited multimodal accessibility. |

| Scalability & Hardware Needs | High: Modular pipeline for classroom-grade hardware; pilot-tested in clean conditions with a roadmap for noisy/ bandwidth-constrained extensions. | High: Web/app-based; scales globally. | High: Cloud-based; accessible worldwide. | Medium: Requires authoring tools; less scalable for non-experts. | High: Mobile-first; scales via app ecosystem. | High: Web-based; LMS integrations; math-focused. |

| Validation & Evidence | Pilot-based: Feasibility on a 5-min STEM clip; staged roadmap for diverse testing (e.g., multilingual, disabilities). | Extensive: Data from millions; A/B tests on mastery learning and AI efficacy. | Extensive: University partnerships; completion-rate analyses. | Research-backed: Studies on adaptive simulations. | Extensive: App metrics; language-retention studies. | Research-backed: Knowledge-space model validated in education studies. |

| Component | Purpose | Technologies Used | Role in Framework | Conceptual Flow Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Point Extraction | Identifies and isolates core instructional concepts (such as definitions and skills) from multimodal content. | Transformer-based NLP (e.g., BERT), OCR, and semantic parsing. | Converts instructional content into modular, meaningful learning units. | Middle layer (content analysis/decomposition) |

| Metadata Generation | Adds descriptive and pedagogical tags (e.g., type, difficulty, modality) to enable intelligent retrieval and alignment. | Heuristic tagging, Bloom’s taxonomy mapping, and prosodic/emotional analysis. | Provides a metadata layer for content organization and adaptive use. | Middle layer (content analysis/decomposition) |

| Learner Profiling | Builds dynamic profiles based on learner preferences, behaviors, and emotional states to guide personalization. | Machine learning, affective computing, behavioral analytics. | Guides decision-making on what and how to present content. | Receiver side (student model) |

| Adaptive Content Delivery | Delivers content in customized formats and sequences across modalities, adapting to learner responses, intended for real-time but offline. | Decision algorithms, multimodal rendering engines, and feedback loops are designed for real-time but tested offline. | Implements learner-facing adaptations to enhance interaction, pending validation. | Receiver side (personalized delivery) |

| Label | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Point | 75.0 | 65.0 | 69.7 |

| Prompt | 90.0 | 85.0 | 87.4 |

| Entity | 80.0 | 70.0 | 74.7 |

| Example | 70.0 | 60.0 | 64.7 |

| Overall (Macro Avg.) | 78.8 | 70.0 | 74.1 |

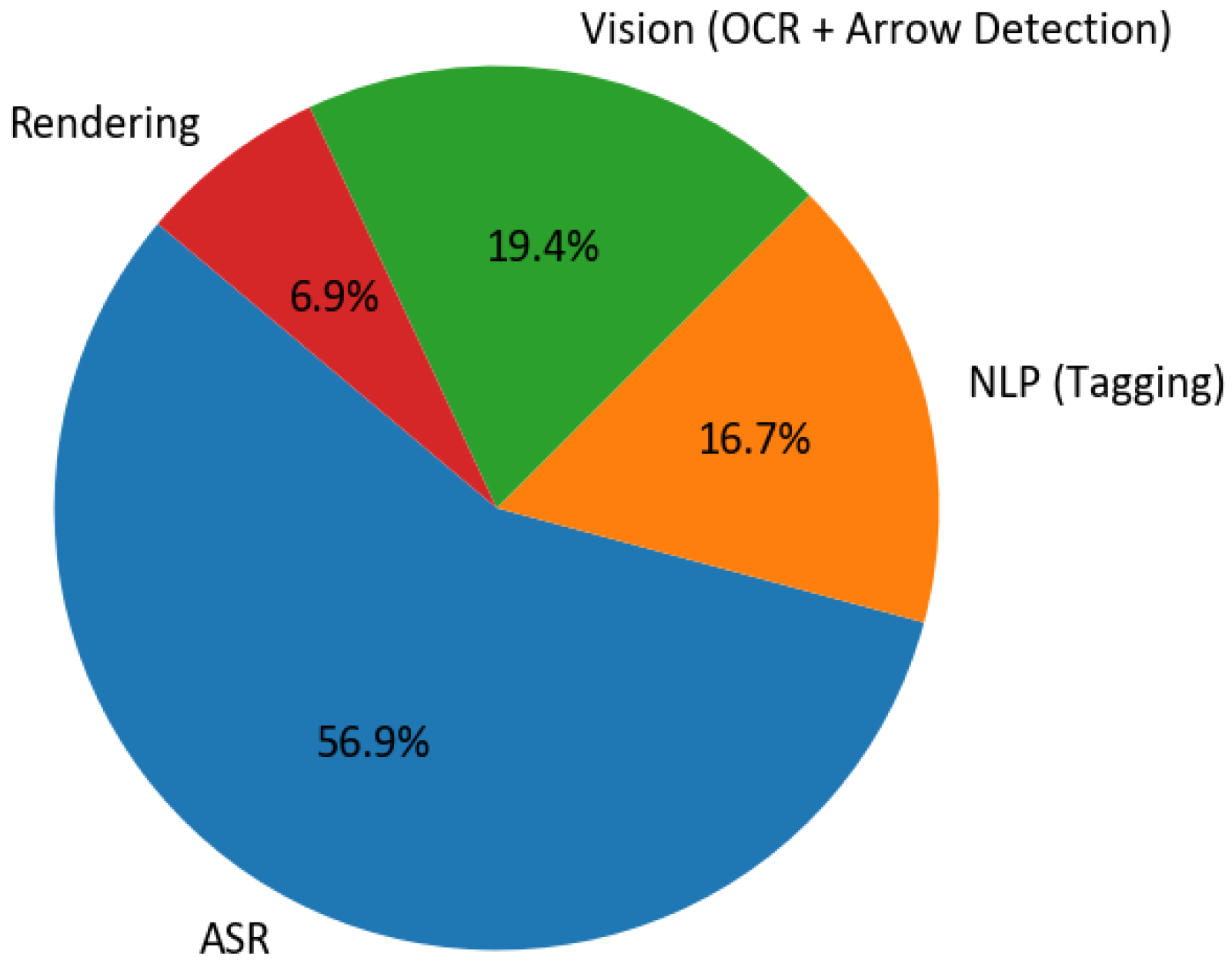

| Stage | Median Time (min) | 90th Percentile (min) |

|---|---|---|

| ASR | 4.1 | 4.5 |

| NLP (Tagging) | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| Vision (OCR + Arrow Detection) | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Rendering | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Total | 7.2 | 7.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeganeh, L.N.; Chen, Y.; Fenty, N.S.; Simpson, A.; Hatami, M. STREAM: A Semantic Transformation and Real-Time Educational Adaptation Multimodal Framework in Personalized Virtual Classrooms. Future Internet 2025, 17, 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120564

Yeganeh LN, Chen Y, Fenty NS, Simpson A, Hatami M. STREAM: A Semantic Transformation and Real-Time Educational Adaptation Multimodal Framework in Personalized Virtual Classrooms. Future Internet. 2025; 17(12):564. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120564

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeganeh, Leyli Nouraei, Yu Chen, Nicole Scarlett Fenty, Amber Simpson, and Mohsen Hatami. 2025. "STREAM: A Semantic Transformation and Real-Time Educational Adaptation Multimodal Framework in Personalized Virtual Classrooms" Future Internet 17, no. 12: 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120564

APA StyleYeganeh, L. N., Chen, Y., Fenty, N. S., Simpson, A., & Hatami, M. (2025). STREAM: A Semantic Transformation and Real-Time Educational Adaptation Multimodal Framework in Personalized Virtual Classrooms. Future Internet, 17(12), 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120564