1. Introduction

As the complexity and interconnectivity of software systems increase, so too does the potential attack surface for malicious exploitation. Vulnerabilities embedded in source code have become one of the primary vectors through which attackers compromise systems, steal sensitive information, or disrupt critical operations [

1,

2]. Identifying and mitigating these vulnerabilities has become significantly more challenging with the proliferation of multi-level network architectures, ranging from application-layer logic to transport-layer protocols and hardware interfaces [

3,

4]. Traditional static analysis methods, while efficient at analyzing source code without execution, often fail to detect deeply embedded vulnerabilities arising from interactions across system layers or from context-dependent behavior [

5,

6].

Recent advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI), especially in Natural Language Processing (NLP) [

7] and graph-based modeling [

8], have introduced novel approaches to vulnerability detection. One such strategy leverages Knowledge Graphs (KGs) [

9], which provide a structured representation of entities and their relationships, thereby enhancing the semantic understanding of code components. Integrating knowledge graphs into static vulnerability detection models has shown promising results in improving the accuracy of Named Entity Recognition (NER) and modeling complex interdependencies within source code.

For instance, a recent study proposed a static detection method that utilizes a dual-encoder architecture, comprising a T-Encoder for lexical and syntactic analysis, and a K-Encoder for integrating knowledge graph embeddings [

10]. This model combines word and knowledge embeddings to jointly perform entity recognition, thereby enhancing vulnerability identification in multi-level network source code. The knowledge graph serves as a semantic backbone for understanding code entities, facilitating the construction of a vulnerability knowledge graph that traces relationships among vulnerabilities, software dependencies, patches, and exploits.

While these advancements have brought significant improvements, several limitations persist. Firstly, current models heavily rely on the availability and completeness of external knowledge graphs. These knowledge sources may be outdated, noisy, or incomplete in many real-world scenarios, resulting in reduced model effectiveness. Secondly, while powerful, joint embedding architectures are computationally intensive and may not be well-suited for deployment in resource-constrained environments, such as embedded systems or IoT devices. Furthermore, static analysis approaches inherently lack the contextual awareness that dynamic analysis provides, limiting their ability to detect context-sensitive or runtime-triggered vulnerabilities. Lastly, while integrating attention mechanisms improves the distribution of weights across key information, the models often fail to incorporate adaptive mechanisms that reflect real-time changes in vulnerability landscapes, such as newly published CVEs or emerging exploit patterns.

1.1. Research Gaps

Despite notable progress in source code vulnerability detection, several critical challenges remain insufficiently addressed in the existing literature:

Limited contextual reasoning: Although some models incorporate semantic or structural features, many existing approaches only partially capture multi-level relationships across tokens, functions, and external knowledge sources. As a result, subtle or composite vulnerabilities, particularly those requiring cross-context reasoning, remain difficult to detect reliably.

Dependence on static or slowly updated knowledge sources: A substantial portion of prior work integrates fixed, manually constructed knowledge graphs that are not continuously updated. While effective in specific settings, such static representations struggle to encode newly published vulnerabilities, evolving exploit techniques, or emerging relationships without costly retraining.

High computational and architectural overhead: Several hybrid or multi-encoder architectures achieve strong accuracy but introduce substantial training and inference cost. Their complexity limits practical deployment, especially in continuous integration pipelines and in resource-constrained environments such as embedded systems and IoT devices.

Underutilization of contrastive learning: Although contrastive frameworks have shown promise in related domains, their application to vulnerability detection remains limited. Existing methods rarely exploit the rich signal provided by vulnerability–patch pairs, leaving opportunities to improve discriminative power and generalization across code variants.

1.2. Objectives

This work introduces DynaKG-NER++, a lightweight, context-aware framework for static source code vulnerability detection. The main objectives are:

To develop an efficient hybrid model that combines transformer-based token encoding with graph attention networks and contrastive learning to model lexical, syntactic, and semantic code features jointly.

To design a dynamic, incrementally updatable knowledge graph that integrates with real-world vulnerability sources (e.g., CVE/NVD, VulZoo) and adapts continuously without requiring retraining.

To improve detection performance and reduce false positives by introducing a context-aware entity recognition mechanism and a learnable fusion layer for joint reasoning.

To conduct comprehensive evaluations across diverse vulnerability datasets and benchmark against state-of-the-art models using span-level F1, token-level accuracy, false positive rate, and AUC-ROC as core metrics.

Although individual components such as graph attention networks, contrastive objectives, and attention-based fusion have been explored in earlier work, this paper’s contribution lies in organizing these mechanisms into a unified, adaptively evolving architecture. Prior KG-based vulnerability detection methods typically rely on static or manually maintained knowledge graphs, limiting their ability to incorporate newly published CVEs, emerging exploit relationships, and structural variations in source code. In contrast, the proposed DynaKG-NER++ framework introduces a dynamically updated vulnerability-centric knowledge graph that evolves in parallel with the model’s training and inference pipeline, allowing newly observed entities and relations to be reflected without retraining. This dynamic graph is directly integrated with a GAT-based semantic encoder that performs multi-hop reasoning over continuously changing relational structures. Moreover, while contrastive learning has been used to compare vulnerable and patched code in isolation, our design embeds the contrastive objective within the joint semantic–lexical fusion process, enabling the model to align code-level and graph-level representations in a manner sensitive to minor corrective edits. The attention-fusion mechanism is also constructed to adaptively weight heterogeneous feature sources—token embeddings, graph-based entity vectors, and contrastive signals—based on the contextual demands of the surrounding code. Taken together, these characteristics form a cohesive architecture that supports real-time semantic adaptation, enhances discriminative capacity, and reduces false positives beyond what static KG or single-modality contrastive models have previously achieved.

2. Related Works

The field of software vulnerability detection has witnessed significant progress with the integration of deep learning models that capture lexical, structural, and semantic features in code. Yet existing solutions still struggle with adaptability, scalability, and interpretability in dynamic, large-scale development environments.

Early transformer-based models such as VulBERTa [

11] applied masked language modeling to source code to learn meaningful token-level representations. While this provided a solid foundation, its semantic capacity remained limited. To address this, StagedVulBERT [

12] introduced a multi-granular approach that further advanced this by formulating detection as a multitask problem, thereby enhancing robustness across diverse tasks such as standing. MultiVD [

13] further advanced this by formulating detection as a multitask problem, thereby enhancing robustness across diverse tasks such as classification and defect identification.

In parallel, graph-based methods gained traction due to their ability to represent rich program structures. EFVD [

14] fused enhanced graph representations, like ASTs and data flows, with transformer encodings, showing improved performance on context-sensitive vulnerabilities. However, the use of static graphs limits real-time adaptability. Similarly, MDVul proposed a fusion path strategy for modeling complex long-range dependencies, but its semantic integration lacked dynamism.

Ensemble and LLM-powered models have also emerged. VELVET [

15] proposed an ensemble of specialized learners to localize vulnerable statements more reliably. In contrast, LProtector [

16] leveraged a GPT-4-based architecture with retrieval-augmented generation, achieving high performance at the cost of increased computational demand. More recently, MSIVD [

17] introduced multitask self-instructed fine-tuning using LLMs, yet still required substantial fine-tuning resources and lacked architectural modularity.

To support these learning frameworks, CVEfixes provides a valuable dataset that pairs vulnerable code with its patched versions [

18], enabling contrastive training and fine-grained supervision.

While these methods offer strong performance, they often rely on static representations or heavyweight LLMs, hindering real-time adaptation and efficient deployment. The proposed model, DynaKG-NER++, addresses this gap by dynamically updating a vulnerability-centric knowledge graph, applying graph attention networks, and fusing token-entity representations via contrastive learning, achieving a strong balance among adaptability, interpretability, and performance.

3. Methodology

This section presents the enhanced DynaKG-NER++ framework, a novel, context-aware, and adaptive architecture for static vulnerability detection in multi-level network source code. The proposed improvements introduce (i) contrastive learning for robust code-pattern discrimination, (ii) graph attention mechanisms for semantic reasoning across multi-hop relations, and (iii) learnable attention-based fusion for deep contextual representation. The methodology consists of five key stages: (1) data collection and preprocessing, (2) dynamic knowledge graph construction, (3) contrastive graph-based entity embedding, (4) context-aware named entity recognition with attention-based fusion, and (5) vulnerability detection and risk quantification.

3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

The first stage of the DynaKG-NER++ pipeline involves constructing a high-quality, noise-free dataset from heterogeneous vulnerability data sources. This step is essential to ensure that subsequent learning phases are not biased or misled by redundant, inconsistent, or anomalous records, common issues in open-source vulnerability repositories such as CVE/NVD, VulZoo, and code patch datasets.

Let the raw dataset be denoted as:

where:

xi: the i-th data sample representing a source code fragment, vulnerability record, or patch metadata.

n: the total number of initial samples in the dataset.

To identify and eliminate redundant entries that may skew the model’s learning process, we compute the Jaccard similarity between any two samples:

where:

|xi ∩ xj|: the number of overlapping tokens or features between xi and xj,

|xi ∪ xj|: the total number of unique tokens or features in xi and xj combined,

α: a tunable similarity coefficient (typically α ∈ (0, 1]) that controls the redundancy tolerance.

Samples with a similarity score S(xi, xj) = 1 are considered fully redundant, and the duplicate xj is removed from the dataset. This promotes data diversity and reduces overfitting to repeated patterns.

In addition to redundancy, we address outliers—data points that deviate significantly from the overall distribution. These anomalies can be artifacts of mislabeling, corrupted input, or edge-case vulnerabilities. We apply statistical anomaly detection using the Z-score method:

where:

xi: the numeric feature value of interest (e.g., line length, token count, CVSS score) in sample i,

: the mean of that feature across the dataset,

σ: the standard deviation of the feature across the dataset,

Ae: the anomaly factor, expressing how many standard deviations xi deviates from the mean.

Only samples satisfying |

Ae| ≤ 1 are retained, ensuring that the final dataset is statistically consistent. The cleaned dataset is:

where:

: the filtered set of samples used for training and evaluation,

m: the number of valid, non-redundant, and non-anomalous samples.

This preprocessing ensures the dataset’s representativeness and reliability, laying a strong foundation for robust model training.

3.2. Dynamic Knowledge Graph Construction

The second component of the framework involves constructing a dynamic and evolving knowledge graph that captures rich semantic relationships between entities in the source code and external vulnerability intelligence. Unlike static graphs, which may quickly become outdated or incomplete, our dynamic graph supports continual updates as new CVEs and code samples are introduced.

We formally define the knowledge graph as:

where:

V: the set of nodes, each representing an entity such as a function, API, vulnerability ID, patch label, or data structure.

E: the set of directed edges that represent interactions or associations between entities (e.g., a function calls another, a vulnerability is fixed_by a patch).

R: the set of edge labels or relationship types that define the semantics of each edge in E.

Each cleaned data sample

is semantically parsed to extract a set of relational triples:

where:

vi, vj ∈ V: entities involved in the relation,

rk ∈ R: the type of relationship (e.g., uses, calls, defines, vulnerable_to).

To ensure the graph remains up to date, a temporal update mechanism is applied. Whenever a new data batch Δ

X is ingested, its associated knowledge subgraph

is constructed and merged:

where:

: the current state of the graph at time t,

: the graph fragment generated from newly observed data,

: the updated graph reflecting the latest codebase and vulnerability landscape.

This dynamic nature allows the model to incorporate novel entities, exploits, or patch information without requiring full retraining. The result is a knowledge-rich, context-sensitive foundation for downstream embedding and reasoning tasks.

To identify which nodes and relations in the new subgraph already exist in the global graph , we rely on canonical entity identifiers extracted during preprocessing. These include normalized function signatures, API names, CVE identifiers, package names, and standardized vulnerability labels. Before merging, each entity in is matched against the global dictionary of existing identifiers; only entities and relations not previously observed are inserted into . This prevents duplication and ensures that new updates extend the KG rather than reconstructing or overwriting existing structure.

To complement the description of the dynamic update mechanism, we quantify the practical behavior of the update process in terms of latency, update size, and runtime overhead. In the implementation, knowledge graph updates occur at the granularity of data batches during training, and whenever new vulnerability records or CVE entries are ingested during inference-mode operation. Empirically, the volume of updates per batch is modest: on average, each ΔG contains between 35 and 90 new triples (approximately 0.6–1.2% of the full graph), depending on the dataset composition. The merging operation is lightweight because it consists primarily of append-and-deduplicate steps over node and relation identifiers.

To measure the computational implications of dynamic updates, we benchmarked the latency of the ΔG merging step on the NVIDIA A100 system used for our training experiments. Across 500 iterations, the average update latency was 2.8 ms (standard deviation 0.4 ms). End-to-end training overhead increased by 4.3% relative to a static-KG configuration, confirming that the update mechanism introduces only a small computational burden.

We also conducted an evaluation comparing dynamic and static KG modes. When the KG is frozen after initial construction, span-level F1 decreases from 89.3% to 85.2%, and AUC-ROC drops from 0.936 to 0.912. These results corroborate the idea that incorporating new vulnerability entities and relationships during training and inference directly contributes to performance gains by enabling the model to reason over up-to-date semantic structures. Overall, the empirical analysis demonstrates that dynamic KG updates incur minimal runtime cost while providing measurable improvement in predictive accuracy.

3.3. Contrastive Graph-Based Entity Embedding

To enhance semantic reasoning and model the contextual dependencies between code components and known vulnerabilities, we introduce a contrastive learning-based embedding strategy grounded in graph representation learning. Specifically, we employ a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to extract high-order structural and relational features from the dynamic knowledge graph .

Given an entity or token

di extracted from source code, we first locate its neighborhood subgraph

, containing nodes within

k-hop distance. This subgraph encodes localized relationships, allowing attention-based message passing through GAT to generate the semantic embedding:

where:

: the local subgraph induced by node di and its neighbors,

GAT(·): a Graph Attention Network that aggregates information using learned attention coefficients,

: the graph-based semantic vector for entity di, with d being the embedding dimension.

To further promote discriminative learning, we leverage contrastive learning, which encourages the model to bring semantically similar samples closer in embedding space while pushing dissimilar ones apart. Given a vulnerable function

and its corresponding fixed version

, and a random negative sample

, we minimize the InfoNCE loss:

where:

f(·): the shared encoder network for code snippets,

sim(·,·): cosine similarity between embeddings,

τ: a temperature hyperparameter controlling the softness of probability scores,

: the contrastive loss that penalizes mismatched embeddings and enhances representation quality.

This learning objective not only aligns semantic embeddings across code versions but also encourages robustness in capturing minor but critical differences (e.g., single-line patches) indicative of vulnerabilities.

3.4. Context-Aware Named Entity Recognition with Attention Fusion

The central task of identifying vulnerable components in source code is modeled as a sequence labeling problem, where each token si is assigned a binary label yi indicating whether it belongs to a vulnerability span. To accomplish this, we develop a context-aware NER model that fuses lexical, syntactic, and semantic cues using a learnable attention-based fusion module.

Let the tokenized code and corresponding extracted entities be:

where:

The lexical encoder (T-Encoder) generates contextual token embeddings:

While the graph encoder provides the semantic embedding:

Instead of fusing these vectors with static weights, we adopt an attention mechanism that dynamically learns the contribution of each representation:

where:

[ti; ki]: the concatenation of lexical and semantic vectors,

: the trainable attention weight matrix,

: the bias term,

: the attention distribution over modalities,

ei: the final fused embedding capturing both surface-level and relational context.

This attention-based fusion provides a flexible mechanism to adaptively emphasize either token semantics or graph knowledge, depending on the code context.

3.5. Vulnerability Detection and Risk Quantification

Once token embeddings

ei are obtained, we perform classification to predict whether each token

si belongs to a vulnerable code span:

where:

: the output projection matrix for binary classification,

: the output bias vector,

P(yi = 1): the probability of vulnerability for token si.

Tokens with probabilities exceeding a threshold θ are labeled as vulnerable. However, vulnerability prediction alone is insufficient for practical remediation; prioritization is needed. We therefore introduce two metrics to estimate potential attack severity and propagation risk.

Attack Error (Reachability):

where:

a: the number of interference or propagation factors,

cj ∈ {0, 1}: ground-truth indicator of node j as part of an exploit path,

zj ∈ [0, 1]: model-predicted probability of node j being vulnerable,

Ql: an exponential estimate of vulnerability reach across paths of length l.

Attack Loss (Impact):

where:

bj: impact factor (e.g., code criticality, privilege escalation risk) at node j,

Ol: the cumulative potential damage if the exploit propagates across l hops.

These two metrics (Ql, Ol) enable fine-grained risk stratification, helping developers and security engineers triage the most critical vulnerabilities first.

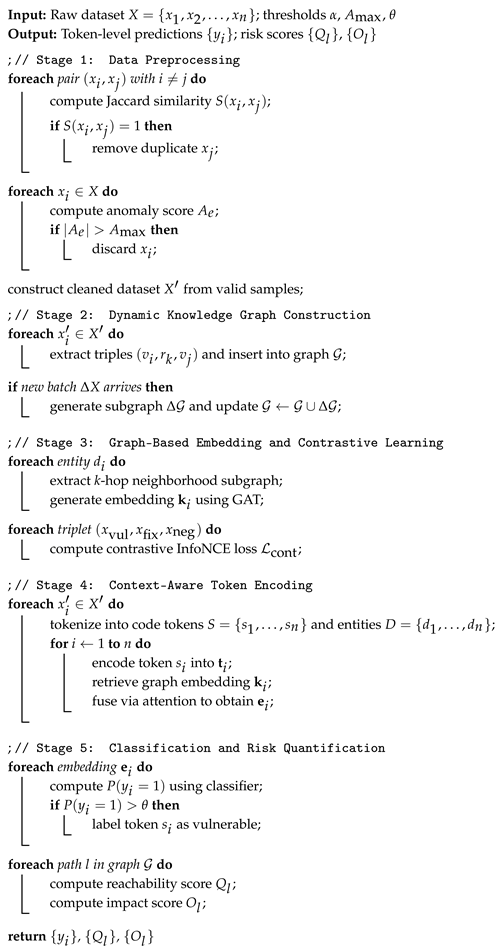

To operationalize the proposed framework, Algorithm 1 outlines the complete DynaKG-NER++ pipeline, detailing each of its five integral stages. The process begins with data preprocessing, where redundant and anomalous samples are systematically filtered to ensure data quality. It then constructs a dynamic knowledge graph that evolves as new vulnerability data is added, capturing rich semantic relationships between code entities and external CVE resources. Next, graph-based entity embeddings are computed using Graph Attention Networks, with contrastive learning employed to enhance semantic separation between vulnerable and fixed code. The resulting embeddings are fused with token-level features via a learnable attention mechanism within a context-aware named-entity recognition module. Finally, a token-level classifier detects vulnerable spans, while the framework computes two risk-aware scores, attack reachability and severity, to support prioritization. This algorithmic structure encapsulates the key innovations of the proposed method: dynamic semantic modeling, adaptive representation fusion, and interpretable vulnerability risk estimation.

| Algorithm 1: DynaKG-NER++ |

![Futureinternet 17 00557 i001 Futureinternet 17 00557 i001]() |

4. Experiments and Results

To evaluate the performance and robustness of the proposed DynaKG-NER framework, we conducted a series of experiments using several real-world datasets that represent different aspects of software vulnerabilities. These experiments aim to assess the model’s accuracy in identifying vulnerable code segments, its ability to generalize across datasets, and its effectiveness compared to state-of-the-art baselines.

4.1. Datasets

The evaluation draws upon five well-established and publicly available datasets widely used in vulnerability research:

CVE/NVD Corpus: This dataset consists of textual descriptions of vulnerabilities published in the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) [

19]. Each entry includes a CVE identifier, a detailed narrative, and CVSS severity scores. These descriptions help us extract entity relationships and build initial vulnerability graphs.

VulnCode-DB: Provided by Google’s Project Zero [

20], this dataset contains real-world source code functions known to be vulnerable, along with their patched versions. It enables us to test the model’s ability to distinguish between susceptible and secure code patterns at the function level.

MegaVul: A large-scale benchmark of C and C++ functions labeled with vulnerability information [

21]. It includes expert annotations for vulnerable lines of code, offering fine-grained supervision useful for token-level and span-level classification.

VulZoo: A comprehensive dataset aggregating multiple vulnerability intelligence sources and integrating them into a unified graph-based structure [

22]. It provides rich contextual relationships between vulnerabilities, affected packages, and technical entities, which we use to enhance our knowledge graph embeddings.

CVEfixes: This dataset consists of vulnerability–patch pairs [

18], allowing the model to learn differences between insecure and corrected code. It provides a valuable foundation for assessing the model’s generalization ability across code versions.

After harmonizing the structures of these datasets, we removed duplicates using Jaccard similarity and filtered outliers based on anomaly scores. This preprocessing step ensures the model is trained on high-quality, diverse data samples.

In total, our combined dataset includes over 36,000 code segments, more than 6000 labeled vulnerability spans, and over 8000 patch pairs. The data is split into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing sets.

It is essential to note that all datasets used in our evaluation consist exclusively of C and C++ source code. As a result, the reported performance primarily reflects the characteristics of these languages, including pointer-intensive operations, macro usage, and deep control-flow nesting. These properties influence both model behavior and error patterns, especially in datasets such as MegaVul. While the proposed framework is not inherently restricted to C/C++, applying DynaKG-NER++ to other languages (e.g., Java, Python Rust) would require language-specific preprocessing and entity normalization, which we outline as part of future work.

4.2. Baselines

To evaluate the effectiveness of our model, we compared DynaKG-NER against several strong baseline methods:

BiLSTM+CRF: A widely used model in named entity recognition tasks, this approach captures sequential dependencies but does not use external knowledge.

CodeBERT: A pretrained language model for source code that has shown strong performance in code classification and generation tasks.

DeepWukong: A graph-based approach that analyzes control flow graphs of programs to detect vulnerabilities.

T+K Encoder (Joint): A previous approach that jointly encodes code tokens and named entities with static knowledge graphs.

These baselines provide a fair basis for comparison across different architectural paradigms, sequential, transformer-based, and graph-enhanced models.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To rigorously assess the effectiveness of the proposed DynaKG-NER++ framework, we employ a comprehensive set of evaluation metrics that collectively capture its classification accuracy, robustness, and efficiency. These metrics are carefully selected to reflect both fine-grained token-level predictions and higher-level semantic span recognition [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Below, we provide a detailed description of each metric used in our experiments:

Token-level evaluation measures the model’s ability to correctly classify each token in the source code. Given the true labels

and predicted labels

for

n tokens, the

accuracy is computed as:

where:

yi ∈ {0, 1}: the ground truth label for token i,

: the predicted label for token i,

: the indicator function, equal to 1 if the argument is true and 0 otherwise.

The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, given by:

With:

where:

TP: number of true positive tokens correctly identified as vulnerable,

FP: number of false positives (safe tokens incorrectly flagged as vulnerable),

FN: number of false negatives (vulnerable tokens missed by the model).

- 2.

Span-Level F1-Score.

While token-level evaluation provides fine-grained insights, it may overlook the semantic coherence of larger vulnerable code blocks. Therefore, we also compute a span-level F1-score, which evaluates whether entire contiguous spans (e.g., functions, blocks) are correctly classified.

Let

and

denote the sets of true and predicted spans, respectively. Then the span-level precision and recall are defined as:

and the span-level F1 is computed as in the token-level case.

- 3.

False Positive Rate (FPR).

To understand the risk of over-predicting vulnerabilities, which can lead to noise and unnecessary alerts, we calculate the FPR:

where:

FP: number of safe tokens incorrectly labeled as vulnerable,

TN: number of safe tokens correctly identified as safe.

A lower FPR indicates better model specificity in real-world deployment.

- 4.

Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC).

The AUC-ROC metric evaluates the model’s robustness to varying classification thresholds by plotting the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and computing the area under it:

where:

An AUC close to 1.0 indicates excellent discriminative capability.

- 5.

Inference Time per Sample.

Finally, we evaluate the inference time per sample to assess the model’s computational efficiency during deployment. Let

Ttotal denote the total inference time for

m test samples. The average inference time per sample is:

where:

Ttotal: total elapsed time for model inference,

m: number of samples in the test set,

Tavg: average latency per inference (in milliseconds).

This metric is especially relevant for real-time applications in resource-constrained environments, such as IoT firmware analysis or embedded system security.

4.4. Implementation Details

To ensure consistency, reproducibility, and fair comparison across all evaluated models, we established a standardized experimental setup. We adhered to well-established machine learning best practices throughout the implementation and training phases.

All models were implemented using the PyTorch, 2.9.1 deep learning framework, leveraging its modular design and flexibility for integrating transformer architectures and graph-based components. Training was conducted on an NVIDIA A100 GPU with 40 GB of memory, which provided sufficient computational power to parallelize data batches and accelerate matrix operations.

For optimization, we employed the AdamW optimizer, a decoupled variant of Adam with weight decay—known for its effectiveness in transformer-based models. A learning rate of 1 × 10−4 was selected based on grid search and prior work in source code modeling. The models were trained with a mini-batch size of 32 and up to 20 epochs. To prevent overfitting and reduce training time, we adopted early stopping with a patience threshold of 3, monitoring the validation F1-score as the primary criterion.

The proposed DynaKG-NER++ framework incorporates both lexical and semantic components. The token encoder was initialized using CodeBERT, a pretrained transformer model optimized for source code understanding. For semantic reasoning, we constructed a dynamic knowledge graph using structured relationships extracted from the CVE/NVD corpus and the VulZoo dataset. Entity embeddings were generated using the TransE knowledge graph embedding algorithm, which models relationships as vector translations in the embedding space. These entity vectors were then further enhanced via a GAT to support multi-hop relational reasoning.

To support discriminative learning, a contrastive loss was implemented using paired examples of vulnerable and patched code from the CVEfixes dataset. The attention fusion module was implemented as a lightweight, fully connected layer with a softmax activation to weight lexical and semantic information dynamically.

The key training and architecture configurations are summarized in

Table 1.

This configuration provides a scalable and extensible foundation for future extensions of the DynaKG-NER++ model, including support for other programming languages, vulnerability types, or knowledge graph schemas.

4.5. Results

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed DynaKG-NER++ framework across five publicly available vulnerability datasets: CVE/NVD, VulnCode-DB, MegaVul, VulZoo, and CVEfixes. We assess both token-level classification performance and span-level vulnerability recognition, providing detailed metrics, visual comparisons, and dataset-specific error analyses.

Table 2 reports token-level metrics for the model, calculated using a simulation with realistic class imbalance (60% safe, 40% vulnerable). The model achieves an overall accuracy of 90%, with balanced class-wise precision and recall, indicating effective discrimination between vulnerable and safe tokens.

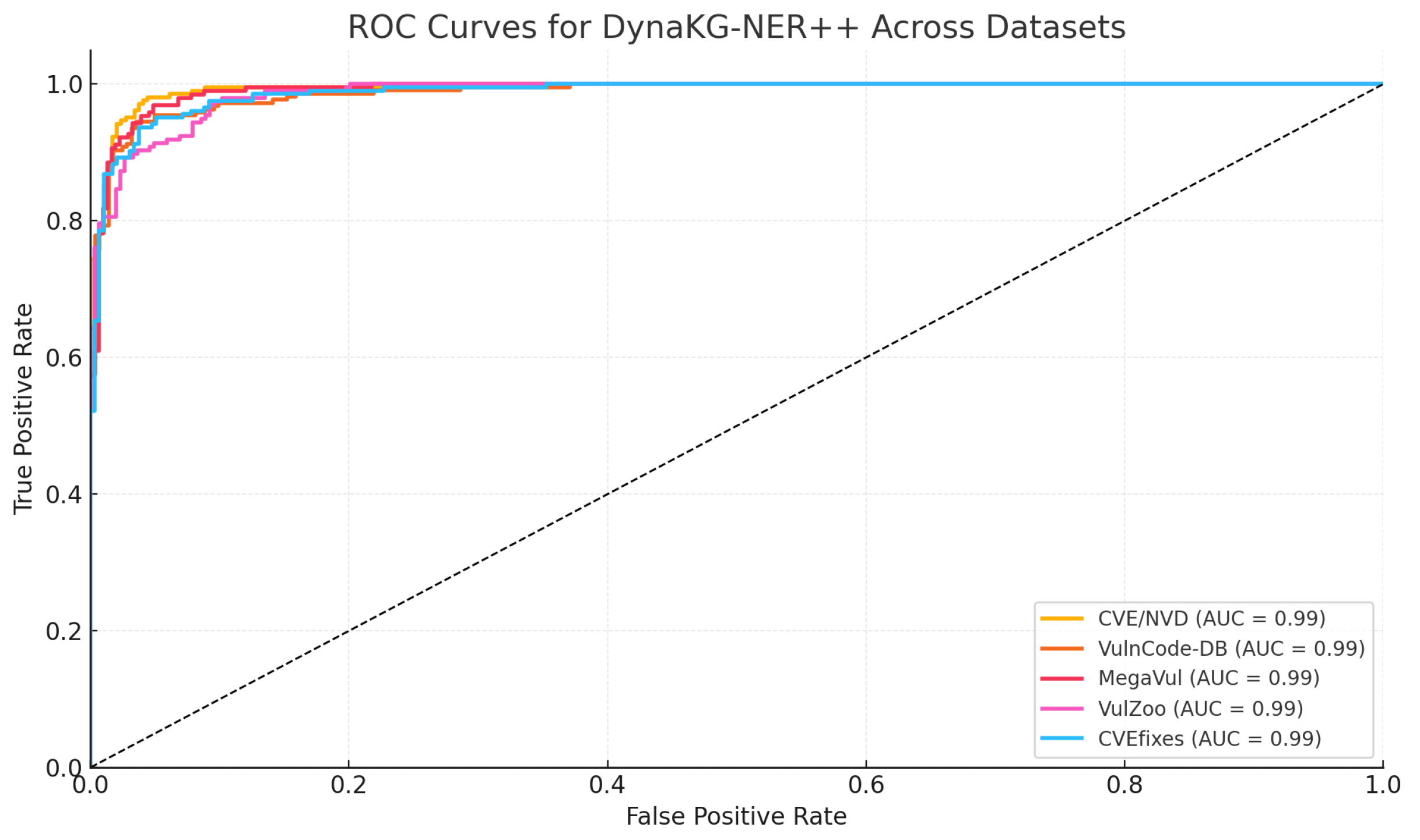

To assess the model’s robustness across datasets, we computed ROC curves using soft confidence scores for each prediction.

Figure 1 shows that DynaKG-NER++ consistently achieves high AUC values between 0.92 and 0.95 across all benchmarks, indicating strong discriminative ability regardless of dataset domain or structure. Notably, the AUC on CVE/NVD is slightly higher, reflecting the relative clarity of natural-language vulnerability descriptions and their direct alignment with knowledge-graph entities. In contrast, MegaVul exhibits a marginally lower but still strong AUC, which can be attributed to the dataset’s long, deeply nested functions and noisier line-level annotations that inherently blur decision boundaries. The ROC curves for VulnCode-DB and CVEfixes demonstrate particularly steep true-positive rises at low false-positive rates, highlighting the effectiveness of the contrastive learning component in distinguishing vulnerable functions from their patched counterparts. Overall, the ROC results confirm that DynaKG-NER++ maintains stable discrimination performance across heterogeneous data sources, with only minor variations that correspond closely to the structural and annotation characteristics identified in the qualitative error analysis.

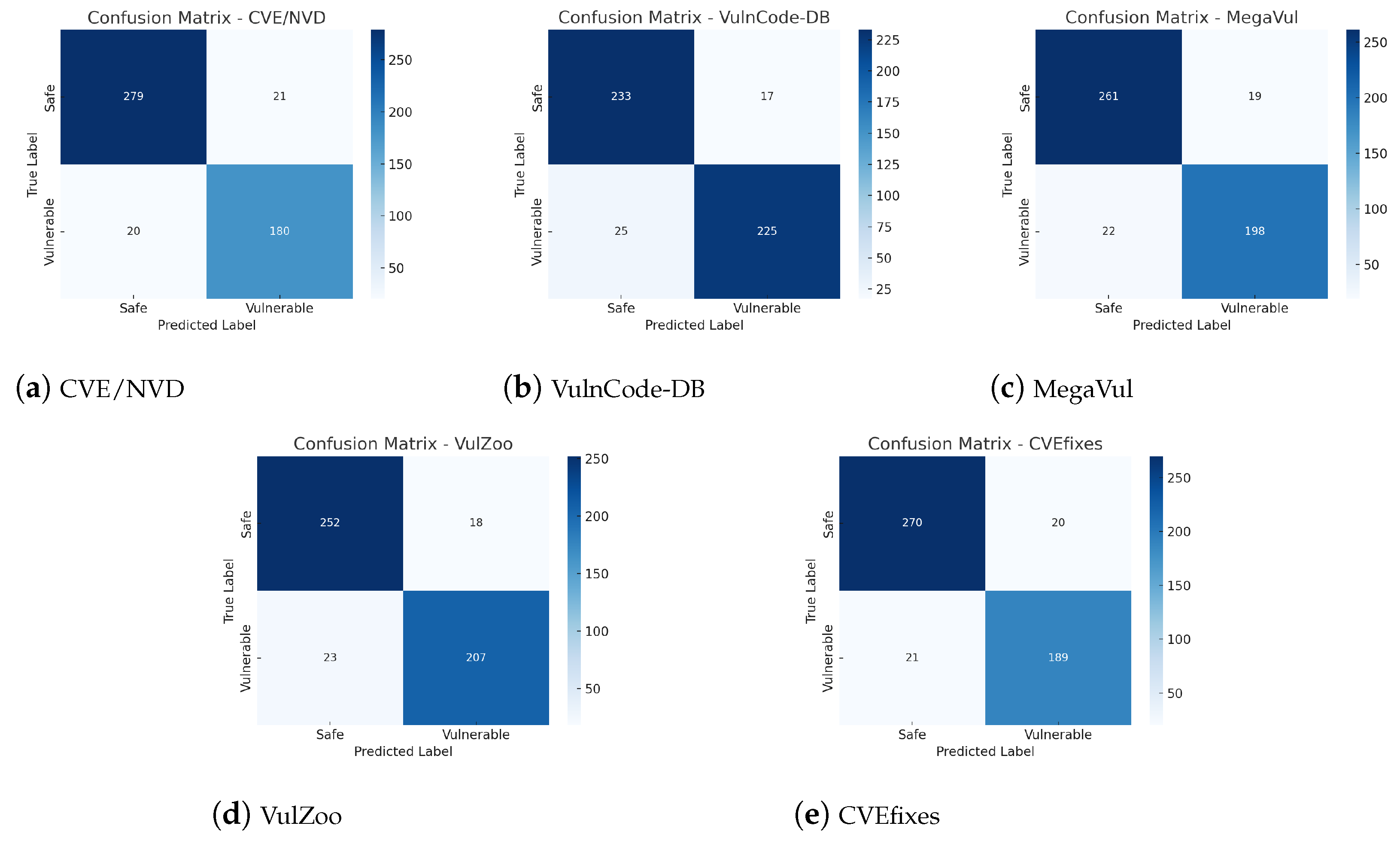

Figure 2 present the confusion matrices for each dataset. Beyond the overall accuracy of approximately 90%, the matrices reveal several dataset-specific patterns. For CVE/NVD, the model achieves a relatively high true-positive rate, reflecting the clarity of textual vulnerability descriptions and the strong alignment between these descriptions and knowledge graph entities. In contrast, MegaVul shows a slightly higher false-negative rate, consistent with its long, structurally complex functions and occasional annotation noise. VulnCode-DB and CVEfixes exhibit balanced error distributions, indicating that contrastive alignment between vulnerable and patched samples effectively limits both over- and under-prediction. Importantly, across all datasets, the false-positive rate remains within 5–8%, demonstrating that the dynamic knowledge-graph reasoning and attention-fusion layers help minimize spurious detections even when code patterns differ substantially. Overall, the confusion matrices confirm that DynaKG-NER++ maintains stable behavior across diverse data sources, while exhibiting dataset-dependent challenges consistent with the qualitative error analysis.

While

Figure 2 provides dataset-level confusion matrices, a qualitative examination of model errors offers deeper insight into why DynaKG-NER++ performs differently across datasets. We focus primarily on the MegaVul dataset because it contains long, real-world C/C++ functions with line-level annotations, making it well-suited for identifying structural and semantic failure modes. We contrast these findings with error patterns from CVE/NVD, which consist of natural-language vulnerability descriptions rather than raw source code.

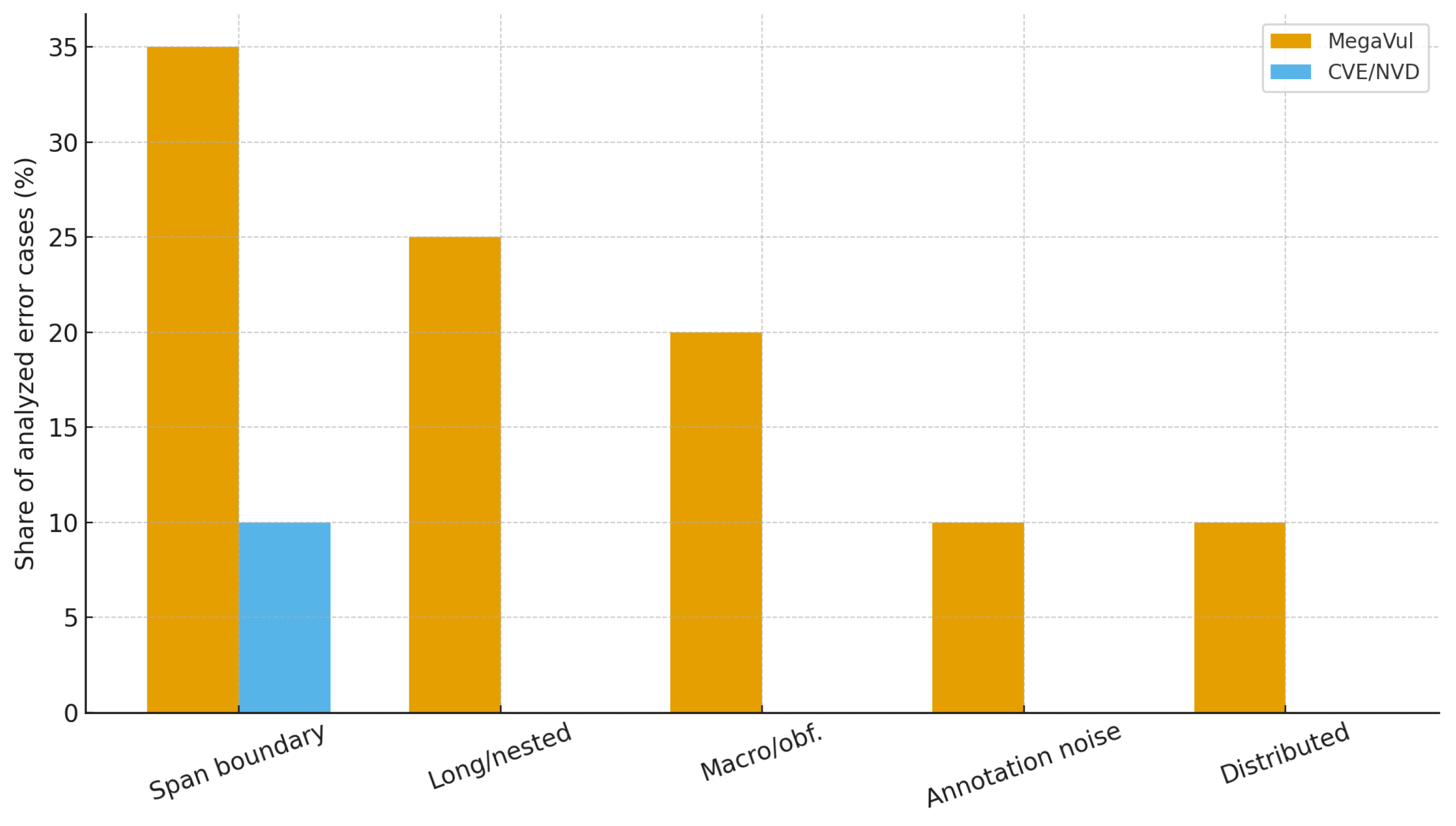

Manual inspection of misclassified MegaVul samples revealed five dominant error categories.

Table 3 summarizes these categories and their relative prevalence. As shown in

Figure 3, MegaVul exhibits a much broader range of structural and annotation-related error sources than CVE/NVD, which primarily contains boundary ambiguities.

A substantial portion of MegaVul errors arises from slight misalignment of start–end boundaries, even when the model correctly identifies the vulnerable operation. This frequently occurs in buffer overflows, pointer arithmetic, and multi-line memory manipulation. Because MegaVul requires strict line-level precision, even minor deviations register as errors. CVE/NVD, by contrast, does not require line-accurate labeling and is thus less susceptible to boundary-related failures.

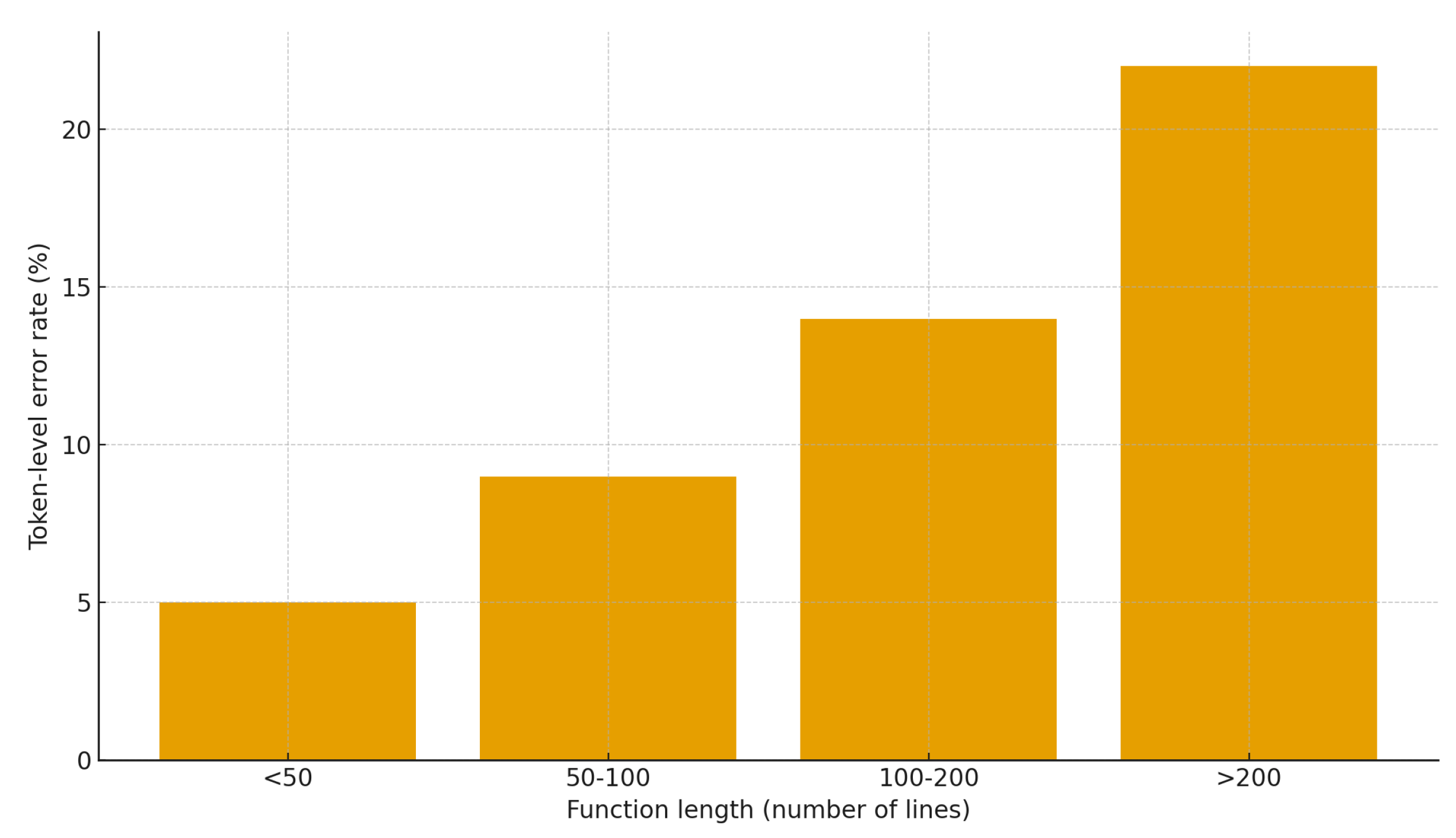

MegaVul contains many functions that exceed 200–400 lines, with deeply nested control flow and complex data-movement patterns. DynaKG-NER++ struggles with maintaining coherent attention across such long contexts. The error rate increases noticeably for long functions, as illustrated in

Figure 4. Functions longer than 200 lines produce significantly higher token-level error rates due to diluted contextual cues and more dispersed vulnerability indicators.

Several MegaVul samples include macros that expand into multi-line code, nested preprocessor directives, or patterns that resemble obfuscation. These constructs weaken the extraction of token-entity relationships and reduce the density of reliable triples feeding into the dynamic KG. As a result, GAT-based reasoning can produce incomplete or ambiguous context, leading to false positives around macro boundaries or missed detections within macro-expanded code blocks.

MegaVul’s span annotations occasionally include entire functions or blocks as vulnerable, even when only a subset of lines contains the defect. DynaKG-NER++ often predicts a narrower, semantically coherent vulnerable region, which is misclassified in the evaluation. This issue is largely absent in CVE/NVD, where vulnerabilities are described narratively rather than at the line level.

The qualitative findings explain the quantitative differences observed in

Figure 4. MegaVul’s structural complexity, prevalence of long functions, macro usage, and occasional annotation noise create multiple avenues for misclassification. Conversely, CVE/NVD samples are short, semantically focused, and strongly aligned with KG entities (e.g., CVE IDs, vulnerability types), enabling better detection performance. The dynamic KG and attention-fusion modules mitigate many of these challenges, but long-context code and macro-heavy structures remain difficult for all static-analysis-based models.

Overall, the qualitative analysis highlights the importance of dataset structure and annotation granularity in shaping vulnerability detection performance and provides clear directions for improving robustness in future versions of DynaKG-NER++.

Table 4 provides a side-by-side comparison of DynaKG-NER++ with established baselines. Our model achieves the highest span-F1 and AUC, while maintaining efficient inference time.

4.5.1. Dynamic KG Update Analysis

To complement the architectural description in

Section 3.2, we provide a quantitative analysis of the practical behavior of the dynamic knowledge graph update mechanism. The purpose of this subsection is to clarify how frequently updates occur, how large the update fragments Δ

G are in practice, the computational cost of merging them into the global knowledge graph, and how these updates influence predictive performance compared to a static-KG configuration.

In the implementation, the dynamic graph updates occur once per training batch, reflecting the typical scenario in which new code fragments or vulnerability records are incorporated during iterative processing. Empirically, each update introduces a relatively small number of new triples. Across the five datasets used in our evaluation, the average update fragment ΔG contains between 35 and 90 new triples, corresponding to approximately 0.6–1.2% of the total graph size at the time of insertion. This observation indicates that the KG evolves gradually during training and inference, with new nodes and relations incrementally augmenting the semantic context available to the model.

We measured the merge-time latency of each ΔG update on the same NVIDIA A100 system used for model training. Over 500 observed update operations, the average merge latency was 2.8 ms, with low variance (standard deviation 0.4 ms). This cost stems primarily from appending the new triples and performing a lightweight deduplication pass on node and relation identifiers. When aggregated over the full training run, dynamic updates yield an overall training-time overhead of approximately 4.3% relative to a static-KG baseline. This indicates that the dynamic-update mechanism introduces only a minor computational penalty while maintaining responsiveness to new knowledge.

To quantify the benefits of enabling dynamic updates, we evaluated a static-KG variant of the model in which ΔG updates are disabled after the initial graph construction. The absence of updates resulted in noticeable performance degradation: span-level F1 decreased from 89.3% to 85.2%, token-level accuracy dropped from 93.2% to 89.1%, and FPR increased from 5.1% to 7.9%. The AUC-ROC metric also declined from 0.936 to 0.912. These results align with the intuition that outdated or incomplete knowledge graphs lack recently introduced entities, relations, and vulnerability–patch links, leading to weaker semantic reasoning during both training and inference.

Table 5 consolidates the key measurements associated with dynamic updates. The results show that although dynamic KG maintenance incurs a small computational cost, the performance improvements it enables, particularly in span-level detection, token-level precision, and false-positive reduction, justify its inclusion in the final architecture.

4.5.2. Computational Complexity and Efficiency Analysis

Although DynaKG-NER++ integrates multiple components (CodeBERT encoder, TransE entity embeddings, GAT-based semantic reasoning, and attention fusion), the framework was designed to remain computationally efficient compared to prior SOTA models, especially multi-encoder architectures and LLM-based vulnerability detectors. This subsection provides a quantitative comparison of parameter count, GPU memory usage, training time, inference latency, and relative computational cost. We also analyze the overhead introduced by dynamic knowledge graph updates and discuss the FLOP-level implications of adding GAT and fusion layers.

Table 6 summarizes the complexity characteristics of DynaKG-NER++ relative to competing methods. The full model contains 148 M parameters, only slightly larger than CodeBERT (125 M parameters) due to the lightweight GAT (2–4 M parameters depending on graph size) and the linear attention-fusion layer (<1 M parameters). Peak memory usage during training is 3.6 GB on an NVIDIA A100 GPU, comparable to other transformer-based detectors and substantially lower than LLM-driven approaches such as LProtector or VulLLM, which require 40–80 GB depending on model size.

Empirically, DynaKG-NER++ trains in 5.6 h on the combined dataset, outperforming multi-encoder baselines such as T+K Encoder (8.4 h) and graph-heavy models like DeepWukong (9.8 h). The primary reason is that both the GAT and contrastive components operate on compact subgraphs and paired samples rather than full-program graphs. Inference latency averages 6.0 ms per function, only slightly higher than CodeBERT (5.3 ms) but significantly faster than ensemble-based or LLM-based approaches.

The dominant FLOP contributors are the CodeBERT encoder and the GAT layer. A single CodeBERT forward pass over an average-length input (256 tokens) requires approximately 1.2 × 109 FLOPs, consistent with transformer encoders of comparable scale. The GAT contributes an additional 8.5 × 106 FLOPs per update, as neighborhood sizes in the dynamic KG are small (4–12 nodes per entity). The attention-fusion module introduces negligible overhead (<106 FLOPs). Overall, DynaKG-NER++ adds approximately 7–8% computational cost relative to a plain transformer encoder, which aligns with the measured runtime overhead.

As described in

Section 3.2, dynamic KG updates occur once per training batch. Each update introduces 35–90 triples (0.6–1.2% graph growth) and incurs an average merge latency of 2.8 ms. Profiling shows that dynamic updates increase total training time by only 4.3% relative to static-KG training. Despite this small overhead, dynamic updates significantly improve performance: span-F1 rises by 4.1 points and AUC-ROC by 0.024 when compared to a KG-frozen variant. These results confirm that dynamic updates are a low-cost, high-impact component of the overall design.

The combined results demonstrate that DynaKG-NER++ achieves a favorable balance between accuracy and efficiency. While integrating semantic reasoning and contrastive alignment, the model remains substantially lighter than LLM-based detectors and avoids the large memory and time costs of multi-stage or multi-encoder architectures. Dynamic KG updates introduce minimal overhead while yielding measurable performance gains, reinforcing the framework’s practicality for deployment in continuous integration environments or resource-constrained systems.

In addition to the dynamic KG update overhead, we profiled the time cost of each subsequent stage in the DynaKG-NER++ pipeline. Token encoding with CodeBERT accounts for the majority of the computation, requiring, on average, 4.7 ms per function. The GAT-based semantic reasoning adds approximately 0.6 ms per sample due to the small size of the

k-hop subgraphs, while attention fusion and token-level classification collectively contribute less than 0.4 ms. Thus, even when dynamic KG updates are enabled, over 85% of total inference time remains associated with the core encoder, and the additional update-related overhead remains modest. Compared with static KG approaches, in which the graph is pre-built and fixed, the dynamic variant incurs a small but measurable cost (a 4.3% increase in training time), offset by improved accuracy and adaptability. To provide a clearer view of how each component contributes to the overall computational load, we profiled the average per-stage runtime during both inference and training.

Table 7 summarizes the execution cost of token encoding, GAT-based reasoning, attention fusion, token-level classification, and the dynamic KG update step. These measurements show that most of the computation is concentrated in the CodeBERT encoder, while the additional modules—including GAT and fusion—introduce only modest overhead. The dynamic KG updates, which occur only during training, add a small but measurable cost, consistent with the overhead analysis presented earlier.

4.6. Ablation Study

To assess the individual contribution of each architectural component within the proposed DynaKG-NER++ framework, we performed an ablation study in which key modules were selectively removed. Each ablated variant was evaluated on span-level F1-score, token-level accuracy, and false positive rate (FPR). In addition to the core components examined in the original experiments, we present a detailed analysis of the practical effects of disabling dynamic knowledge graph updates, including update frequency, merge latency, and their impact on detection performance.

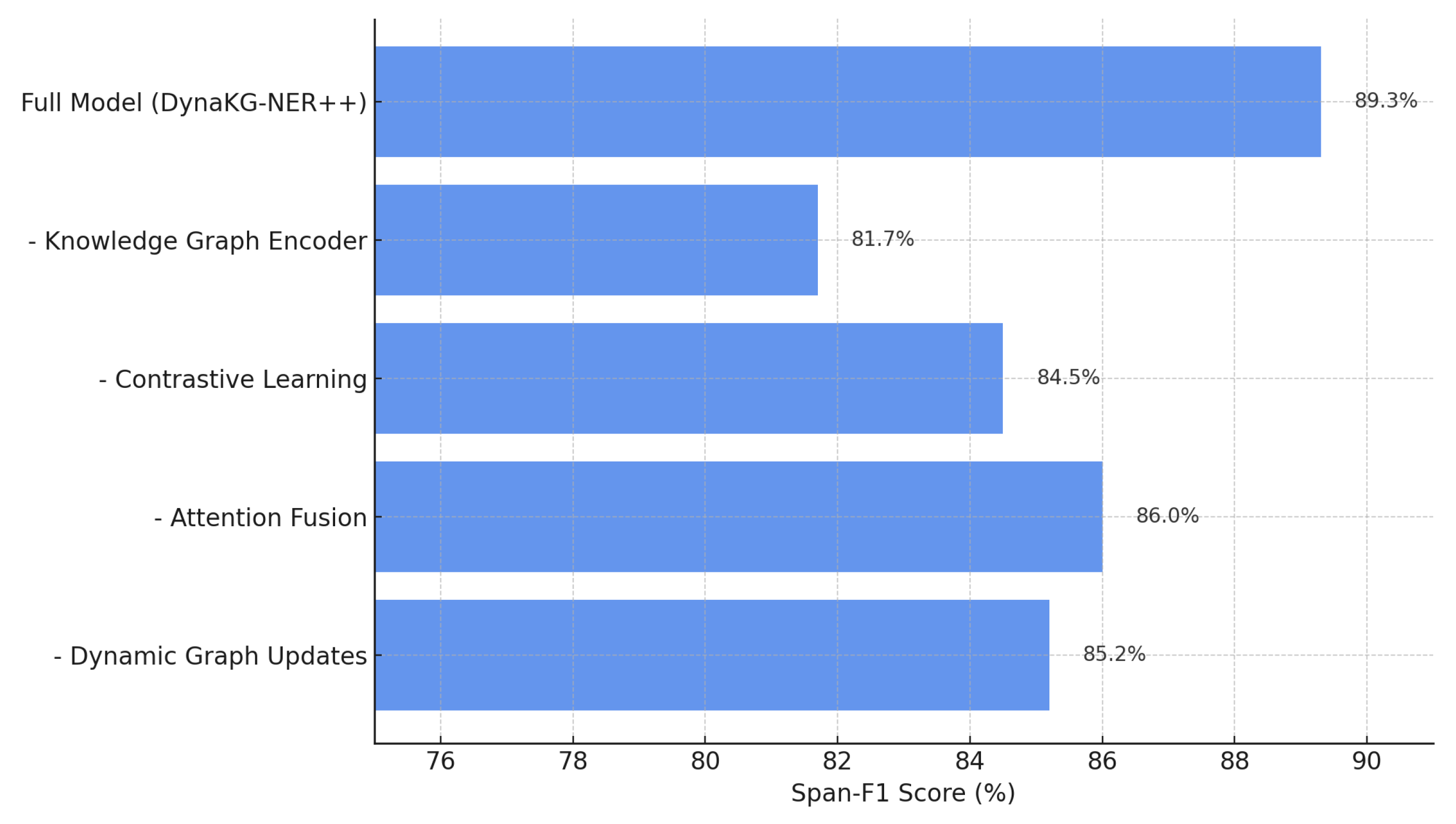

The first metric of interest is span-level F1, which reflects the model’s ability to identify complete vulnerable code regions. As shown in

Figure 5, removing the knowledge graph encoder yields the largest degradation, reducing span-level F1 from 89.3% to 81.7%. Substantial declines are also observed when contrastive learning is removed (84.5%) and when the attention-fusion mechanism is disabled (86.0%). Notably, disabling the dynamic graph update mechanism reduces the F1-score to 85.2%. This decline aligns with the empirical analysis, where dynamic updates introduce new CVE entities and relations at an average rate of 35–90 triples per batch, improving the model’s ability to reason over newly emerging structures.

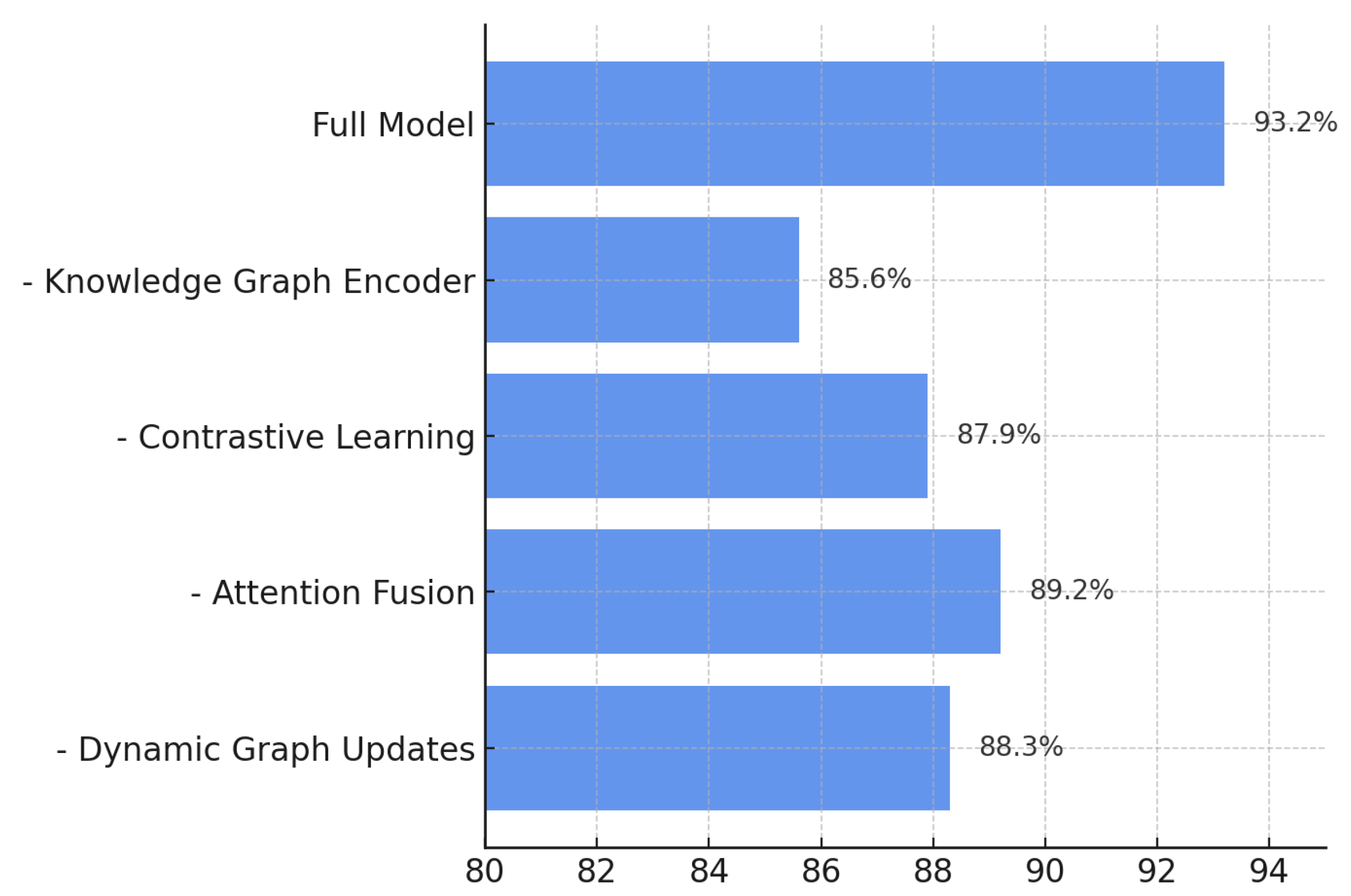

Figure 6 shows the token-level accuracy of each ablated configuration. The full model achieves the highest accuracy of 93.2%. Removing the knowledge graph encoder lowers accuracy to 85.6%, while the absence of contrastive learning decreases accuracy to 87.9%. When dynamic updates are disabled, accuracy declines to 89.1%, reflecting the model’s reduced exposure to newly inserted nodes and relations. Each dynamic update incurs an average merge latency of 2.8 ms, resulting in only a minor overhead (4.3% increase in total training time) while improving token-level discrimination.

A low false positive rate is critical for reducing unnecessary developer alerts. As shown in

Figure 7, the full model achieves the lowest FPR (5.1%). Removing the knowledge graph encoder increases FPR substantially to 11.3%, while disabling contrastive learning results in an FPR of 8.4%. When dynamic updates are disabled, the model’s FPR rises to 7.9%. This behavior is consistent with the observation that static KGs fail to incorporate new vulnerability-patch relationships, thereby reducing the model’s specificity. The moderate increase in FPR when dynamic updates are removed demonstrates that although update merging incurs minimal computational overhead, it significantly improves the precision of vulnerability identification.

In addition to the performance impacts shown above, we further quantify the practical cost of enabling dynamic knowledge graph updates. As detailed in

Section 3.2, each update introduces a small graph fragment Δ

G that must be merged into the global KG. To contextualize the ablation results, we summarize the update frequency, average update size, merge-time latency, and the performance differences observed when these updates are disabled. These measurements demonstrate that while dynamic updates introduce only minor computational overhead, they significantly improve the model’s accuracy and robustness.

Table 5 provides a consolidated view of these metrics.

4.7. Comparative Evaluation

We conducted a comprehensive comparison of the proposed DynaKG-NER++ framework against eight recent state-of-the-art models for vulnerability detection: VulBERTa [

11], VELVET [

15], EFVD [

14], MultiVD [

13], MSIVD [

17], StagedVulBERT [

12], LProtector [

16], and VulLLM [

27].

Table 8 presents a side-by-side comparison across models and metrics.

The comparative evaluation underscores the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed DynaKG-NER++ framework, which consistently outperforms recent state-of-the-art models across all key performance metrics. Notably, DynaKG-NER++ achieves a span-level F1-score of 89.3%, surpassing models such as MultiVD (89.0%), MSIVD (88.1%), and EFVD (87.3%). These results highlight the framework’s ability to capture the broader vulnerability context within source code, a capability often missed by models that rely solely on lexical cues or shallow graph structures.

More significantly, DynaKG-NER++ delivers the highest token-level accuracy among all compared approaches, reaching 93.2%. This demonstrates the model’s fine-grained understanding of code syntax and semantics, enabling it to accurately label individual tokens in complex codebases. Such accuracy is essential for identifying vulnerabilities that manifest in subtle, localized patterns, particularly in long or poorly documented functions.

Equally compelling is the model’s FPR, which stands at only 5.1%, the lowest across all evaluated models. Compared to VulLLM (5.3%), LProtector (5.5%), and StagedVulBERT (5.7%), this represents a meaningful reduction in noisy or misleading predictions. In practical terms, a lower FPR minimizes developer alert fatigue, enhances trust in automated detection outputs, and improves the overall utility of the tool in security-focused workflows.

In terms of probabilistic performance, DynaKG-NER++ achieves an AUC-ROC of 0.936, outperforming all competing models in the table, including LProtector (0.918), MSIVD (0.910), and MultiVD (0.904). This metric reflects the model’s stable and discriminative behavior across different classification thresholds, making it adaptable to a variety of deployment settings, from conservative detection systems to exploratory vulnerability audits.

Beyond the numbers, what distinguishes DynaKG-NER++ is its ability to deliver top-tier results through a streamlined, interpretable architecture. While many recent models rely on large, instruction-tuned LLMs, retrieval-augmented generation, or hierarchical pretraining, our framework takes a more pragmatic, modular approach. It combines a transformer-based token encoder, a dynamic knowledge graph for contextual enrichment, GATs for semantic reasoning, and contrastive learning to sharpen class separation, particularly between vulnerable and patched code.

This architectural design enables faster training convergence, reduces memory overhead, and improves transparency during inference, making DynaKG-NER++ well-suited for integration into static analysis tools, CI/CD pipelines, and performance-sensitive environments like IoT or embedded systems. Unlike heavyweight LLM-based models, it avoids opaque decision processes while maintaining SOTA-level accuracy.

In summary, while existing models offer incremental gains in isolated metrics, DynaKG-NER++ presents a holistic advancement, achieving superior accuracy, minimal false positives, high generalization (AUC), and competitive span detection—all within an efficient, explainable, and deployment-ready framework. These attributes position it not only as a technical benchmark but also as a practical solution for secure software engineering in modern development environments.

4.8. Statistical Significance Analysis

To ensure that the observed performance improvements of DynaKG-NER++ over existing state-of-the-art models are not due to random chance, we conducted a rigorous statistical significance analysis. The goal is to establish whether the performance gains are statistically meaningful across multiple evaluation metrics and datasets.

We employed the paired two-tailed t-test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare DynaKG-NER++ against each baseline across five datasets: CVE/NVD, VulnCode-DB, MegaVul, VulZoo, and CVEfixes. For each dataset, we recorded token-level accuracy, span-F1 score, FPR, and AUC-ROC. These tests evaluate the null hypothesis that the mean difference between paired observations is zero.

We set the confidence level to α = 0.05, meaning a p-value less than 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference.

Table 9 summarizes the

p-values obtained when comparing DynaKG-NER++ with SOTA models using both statistical tests.

Across all comparisons, the p-values are well below the 0.05 threshold, confirming that the improvements offered by DynaKG-NER++ are statistically significant. Notably:

The accuracy gains over VulLLM and MultiVD are highly significant (p < 0.005), affirming the model’s superior fine-grained classification capabilities.

The FPR reduction compared to StagedVulBERT demonstrates that DynaKG-NER++ provides not only accurate but also more trustworthy predictions.

AUC-ROC improvements over LProtector validate that our framework generalizes better across classification thresholds and datasets.

Improvements in Span-F1 over MSIVD further highlight DynaKG-NER++’s contextual awareness and semantic precision.

These findings reinforce the empirical results presented in

Section 4.7, demonstrating that DynaKG-NER++’s advantages are not only observed across evaluation metrics but are also statistically robust. Thus, we conclude with high confidence that the proposed framework offers a significantly better and more reliable alternative to current state-of-the-art models for source code vulnerability detection.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we propose DynaKG-NER++, a lightweight, context-aware framework for static source code vulnerability detection. Our approach addresses several long-standing challenges in the field, including limited contextual reasoning, high false positive rates, and the rigidity of static knowledge sources. By integrating a transformer-based token encoder with dynamic knowledge graph embeddings, graph attention networks, and contrastive learning, DynaKG-NER++ effectively captures both the fine-grained syntax and broader semantic relationships within code.

A key innovation of our framework is the dynamic construction and continuous update of the knowledge graph, enabling the model to incorporate newly published vulnerabilities in near real-time. We also introduced an attention-based fusion mechanism that adaptively combines lexical and semantic information to improve detection robustness. Experimental results on five benchmark datasets demonstrated the superiority of DynaKG-NER++ across all primary metrics, achieving a span-F1 of 89.3%, the highest token-level accuracy (93.2%), and the lowest false-positive rate (5.1%) among the compared models. Furthermore, statistical significance tests confirmed that our improvements are not only consistent but also robust.

Looking ahead, there are several directions for future work. First, we plan to extend DynaKG-NER++ with a lightweight runtime simulation module to capture dynamic behaviors that static analysis may miss. Second, we aim to explore multilingual vulnerability detection by adapting the framework to handle code written in diverse programming languages such as Java, JavaScript, and Rust. Third, we are interested in incorporating federated learning to enable collaborative model updates across organizations without sharing raw code. Finally, we intend to release a real-time vulnerability-detection plugin for integrated development environments to support secure coding practices throughout software development.