A Proposal of a Scale to Evaluate Attitudes of People Towards a Social Metaverse

Abstract

1. Introduction

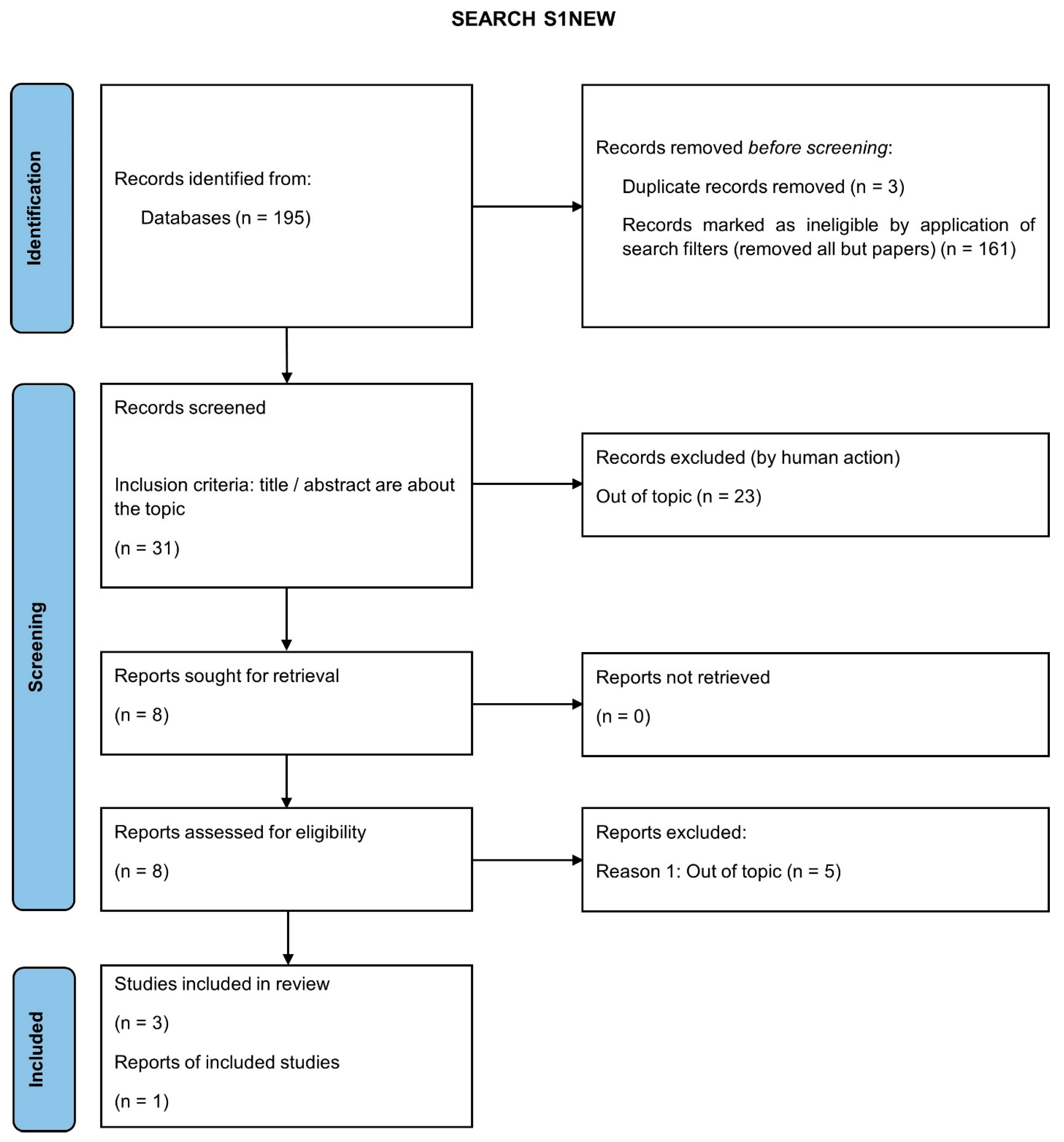

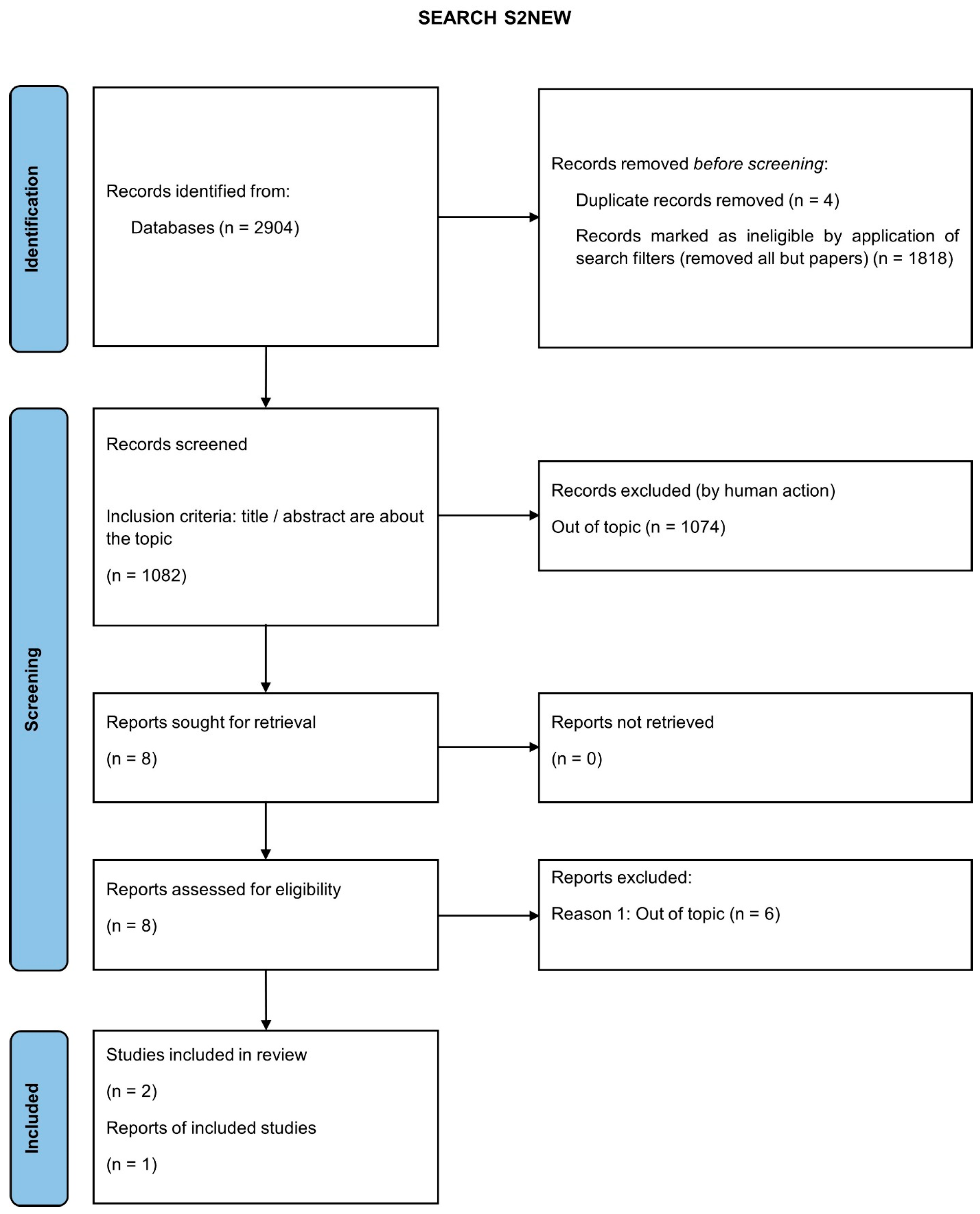

2. Related Works

3. Development of the Questionnaire

4. Questionnaire Administration

5. Results

5.1. General Information

5.2. Checks for Feasibility of Exploratory Factor Analysis

5.3. Extraction of Factors and Processing

- C1 (in the end not used): Select the items with a loading cutoff of 0.35. Thus, the items must have a loading ≥ 0.35. This is a simple pragmatic criterion.

- C2: Select the items with a loading cutoff ≥ 0.3 as factor markers AND a factor must have at least three markers [45]. Whenever possible, in practice more severe cutoff values were used (such as, for example, ≥0.4 or more).

- C3: Select items so that the absolute value of {item’s first maximum loading amongst factors—item’s second maximum loading amongst factors} ≥ 0.3 [58].

- C4: First apply C3 and then apply C2 to the items resulting from C3. This criterion helps in letting the factors emerge with at least three markers and featuring both a good enough distance of the highest loading value from other loading values and a sufficient loading cutoff value.

5.4. Interpretation of Factors

5.5. Scoring

- Scores ≤ 15 express just a negative attitude towards the social metaverse;

- Scores in (16, 21) express a slight negative attitude towards the social metaverse;

- Scores in (22, 39) express a neutral position;

- Scores in (40, 45) express a slight positive attitude;

- Scores ≥ 46 express a positive attitude.

6. Considerations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

- Doing fitness while immersed in virtual scenarios draws me (+) (T7)

- 2.

- Rather than facing a trip (maybe long and expensive) to meet up with somebody, I would prefer to meet somebody within virtual social worlds without moving from home (+) (T6)

- 3.

- In my opinion, doing and sharing experiences while immersed in virtual social worlds would not be something better than reality (−) (T6)

- 4.

- In my opinion, experiences within virtual social worlds, even in company of other people, could be an alternative to experiences of reality (+) (T4)

- 5.

- The immersion in virtual social worlds offers many possibilities: in my opinion, it risks making reality “unnecessary” (−) (T7)

- 6.

- I am afraid that social relations made by users interacting in virtual social worlds might impoverish people (−) (T7)

- 7.

- The idea of meeting up with my friends within the virtual social worlds doesn’t mean a thing to me (−) (T5)

- 8.

- I think that exploring virtual, imaginary and fantasy social worlds makes little sense (−) (T6)

- 9.

- I think that, in virtual social worlds, doing what I want and sharing my experiences can better my well-being (+) (T6)

- 10.

- The thought that situations I desire can be realized within virtual social worlds cheers me up (+) (T6)

- 11.

- If there were something limiting my life, I think I could overcome it by getting immersed in virtual social worlds and attending experiences that I would select myself (+) (T7)

- 12.

- The idea of having experiences with my friends in virtual social worlds leaves me indifferent (−) (T5)

- 13.

- I think that it is nice to have experiences with my relatives within virtual social worlds, instead of meeting up really (+) (T5)

- 14.

- A future where we meet within virtual social worlds worries me (−) (T7)

- 15.

- I think that I could spend less time on certain things in real life and, instead, do them while immersed in virtual social worlds (+) (T4)

- 16.

- I like more meeting up and having experiences with people in reality rather than in virtual social worlds (−) (T5)

- 17.

- I don’t like the idea of “being away” from reality around me while immersed in virtual social worlds (−) (T7)

- 18.

- The students could attend classes by getting immersed in a virtual social world rather than being at school: I don’t like this scenario (−) (T7)

- 19.

- In my opinion the experiences and sharing in virtual social worlds will not be as satisfying as experiences and sharing in real life (−) (T7)

- 20.

- The idea of meeting up with my relatives in virtual social worlds interests me a great deal (+) (T5)

- 21.

- In virtual social worlds, I would like to attend public events and situations, such as going to concerts, to cinema, to theater, to club (+) (T4)

- 22.

- In my opinion it is better to meet up with people within virtual social worlds directly, rather than having to move on purpose to see each other (+) (T6)

- 23.

- If I had trouble travelling, being able to meet up anyway with people in virtual social worlds would be consolatory for me (+) (T6)

- 24.

- In my opinion, the possibility of working while immersed in a virtual office and of attending meetings with people in customized virtual environments is interesting (+) (T7)

- 25.

- In the virtual social worlds there are many occasions of awesome experiences, but I don’t think that this can better the life of people (−) (T7)

- 26.

- I wouldn’t like to wear all the time on the head a display device for getting immersed in virtual social worlds (−) (T7)

- 27.

- In my opinion, frequenting virtual social worlds can better life (+) (T6)

- 28.

- I deem it positive to be able to meet up easily with other people within virtual social worlds for the purpose of activities, meetings or work (+) (T6)

- 29.

- The possibility of playing sports and games within virtual social worlds with other people “present” in virtual is a nice thing (+) (T4)

- 30.

- I would be fine spending, during the week, 4–10 h immersed in virtual social worlds (+) (T7)

- 31.

- Frequenting, exploring virtual social places created by users are pointless things (−) (T6)

- 32.

- Playing sports within virtual social worlds is an interesting thing (+) (T4)

- 33.

- I think that attending public entertainment events within virtual social worlds is a good idea because I can have fun and feel at peace (+) (T4)

- 34.

- Doing things in virtual social worlds rather than in reality can be positive (+) (T7)

- 35.

- I would like to participate in astonishing events within virtual social worlds, as for example attending concerts in between the planets, or going to amusement parks stretching to the horizon, or shopping in ancient Rome (+) (T7)

- 36.

- I think I will use the virtual social worlds (+) (T7)

- 37.

- If there was something of my appearance I did not like, I don’t think that participating in virtual social worlds with a different appearance would make me feel better (−) (T6)

- 38.

- The possibility of customizing my appearance in virtual social worlds leaves me indifferent (−) (T6)

Appendix C

| Item | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | −0.132763 | 0.012754 | 0.131381 | 0.671440 | −0.049754 |

| Item 2 SQRT | 0.383504 | −0.144823 | 0.030766 | −0.058296 | 0.549424 |

| Item 4 | 0.295643 | 0.060137 | 0.005948 | 0.076512 | 0.292022 |

| Item 9 | 0.591406 | 0.072333 | −0.065378 | −0.004811 | 0.245362 |

| Item 10 | 0.388485 | 0.095122 | 0.163391 | 0.075273 | 0.092008 |

| Item 11 | 0.898511 | −0.342209 | 0.018771 | −0.166572 | 0.091278 |

| Item 13 SQRT | 0.090939 | 0.396518 | −0.130142 | 0.249908 | 0.094728 |

| Item 15 SQRT | 0.448326 | 0.052207 | 0.070533 | −0.009281 | 0.093649 |

| Item 20 SQRT | 0.297697 | 0.047588 | 0.029060 | 0.345832 | 0.107656 |

| Item 21 | −0.155326 | −0.023716 | 0.775636 | 0.066861 | 0.154925 |

| Item 22 LOG10 | −0.019480 | 0.158638 | −0.016098 | −0.090576 | 0.731703 |

| Item 23 | 0.838957 | −0.269149 | 0.004650 | 0.067090 | −0.086160 |

| Item 24 | 0.342254 | −0.074052 | 0.267810 | 0.249488 | 0.101702 |

| Item 27 | 0.459428 | 0.379894 | 0.012175 | 0.021931 | −0.031281 |

| Item 28 | 0.452885 | −0.187597 | 0.477014 | 0.130330 | −0.041821 |

| Item 29 | 0.157416 | 0.068090 | −0.117981 | 0.800872 | −0.112962 |

| Item 30 | 0.196330 | 0.370094 | 0.144637 | 0.102608 | 0.078379 |

| Item 32 | −0.171962 | −0.045459 | 0.071168 | 0.975909 | −0.018260 |

| Item 33 | −0.110675 | 0.081072 | 0.710433 | 0.051714 | 0.133592 |

| Item 34 | 0.518281 | 0.095775 | 0.124412 | −0.102455 | 0.180196 |

| Item 35 | 0.155708 | −0.071850 | 0.642595 | −0.036856 | −0.181766 |

| Item 36 | 0.185262 | 0.236632 | 0.544262 | −0.042167 | −0.080261 |

| Item 6 LOG10 | 0.007035 | 0.717469 | −0.057890 | −0.075613 | 0.074661 |

| Item 7 SQRT | 0.215180 | 0.484082 | 0.124925 | 0.018606 | 0.002164 |

| Item 8 | 0.424239 | 0.361446 | 0.150922 | −0.095642 | −0.123010 |

| Item 14 SQRT | 0.320529 | 0.437234 | 0.098750 | −0.044062 | −0.110539 |

| Item 16 LOG10 | −0.193258 | 0.474126 | −0.033289 | 0.022751 | 0.346328 |

| Item 17 LOG10 | −0.322042 | 0.778293 | 0.082219 | −0.023162 | 0.006245 |

| Item 19 LOG10 | −0.076522 | 0.587988 | −0.144339 | 0.127401 | 0.044701 |

| Item 25 | 0.613832 | 0.433563 | −0.384888 | −0.016246 | −0.053472 |

| Item 26 LOG10 | −0.238355 | 0.706314 | 0.166809 | −0.059513 | 0.017867 |

| Item 31 | 0.320862 | 0.301634 | 0.330406 | −0.023566 | −0.158973 |

| Item | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.338678 | 0.359286 | 0.461192 | 0.670345 | 0.138880 |

| Item 2 SQRT | 0.477266 | 0.310767 | 0.351829 | 0.259260 | 0.635815 |

| Item 4 | 0.497631 | 0.421722 | 0.384909 | 0.370613 | 0.450263 |

| Item 9 | 0.689096 | 0.536316 | 0.449255 | 0.411289 | 0.473309 |

| Item 10 | 0.642677 | 0.537808 | 0.555251 | 0.487539 | 0.351694 |

| Item 11 | 0.608417 | 0.236195 | 0.343168 | 0.203950 | 0.265996 |

| Item 13 SQRT | 0.464769 | 0.562421 | 0.349845 | 0.472882 | 0.301906 |

| Item 15 SQRT | 0.561833 | 0.435793 | 0.424129 | 0.355033 | 0.304762 |

| Item 20 SQRT | 0.594272 | 0.509182 | 0.510894 | 0.596626 | 0.346001 |

| Item 21 | 0.441073 | 0.409314 | 0.754187 | 0.499804 | 0.369997 |

| Item 22 LOG10 | 0.305877 | 0.354142 | 0.253661 | 0.184746 | 0.751755 |

| Item 23 | 0.660339 | 0.326981 | 0.419963 | 0.385108 | 0.154076 |

| Item 24 | 0.653351 | 0.499128 | 0.645824 | 0.607548 | 0.366153 |

| Item 27 | 0.734321 | 0.709327 | 0.539131 | 0.506817 | 0.293906 |

| Item 28 | 0.698854 | 0.462656 | 0.738375 | 0.581379 | 0.260343 |

| Item 29 | 0.554026 | 0.524473 | 0.497193 | 0.825016 | 0.158119 |

| Item 30 | 0.641352 | 0.678054 | 0.580011 | 0.542763 | 0.367789 |

| Item 32 | 0.409521 | 0.423893 | 0.546034 | 0.889225 | 0.199516 |

| Item 33 | 0.498765 | 0.491320 | 0.762039 | 0.522971 | 0.377831 |

| Item 34 | 0.676238 | 0.538227 | 0.519650 | 0.386487 | 0.425997 |

| Item 35 | 0.441202 | 0.318987 | 0.619253 | 0.371480 | 0.059229 |

| Item 36 | 0.656823 | 0.625969 | 0.749284 | 0.525163 | 0.250814 |

| Item 6 LOG10 | 0.454648 | 0.673576 | 0.337067 | 0.321106 | 0.300974 |

| Item 7 SQRT | 0.648580 | 0.717956 | 0.559004 | 0.500624 | 0.310355 |

| Item 8 | 0.674406 | 0.645366 | 0.537818 | 0.420513 | 0.195998 |

| Item 14 SQRT | 0.624125 | 0.652508 | 0.497523 | 0.424639 | 0.193811 |

| Item 16 LOG10 | 0.261456 | 0.460455 | 0.243734 | 0.255783 | 0.442866 |

| Item 17 LOG10 | 0.265913 | 0.589398 | 0.303876 | 0.284844 | 0.192378 |

| Item 19 LOG10 | 0.330913 | 0.540355 | 0.239687 | 0.337856 | 0.219404 |

| Item 25 | 0.631874 | 0.612548 | 0.243586 | 0.330752 | 0.204297 |

| Item 26 LOG10 | 0.338455 | 0.608272 | 0.383388 | 0.313806 | 0.227785 |

| Item 31 | 0.676953 | 0.644294 | 0.647906 | 0.501971 | 0.180112 |

| Item | Initial | Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.484943 | 0.463400 |

| Item 2 SQRT | 0.492877 | 0.483074 |

| Item 4 | 0.421399 | 0.334616 |

| Item 9 | 0.555766 | 0.531110 |

| Item 10 | 0.505856 | 0.460607 |

| Item 11 | 0.517916 | 0.462592 |

| Item 13 SQRT | 0.506879 | 0.366521 |

| Item 15 SQRT | 0.421617 | 0.329796 |

| Item 20 SQRT | 0.572881 | 0.459571 |

| Item 21 | 0.623624 | 0.597488 |

| Item 22 LOG10 | 0.447652 | 0.579466 |

| Item 23 | 0.516095 | 0.480504 |

| Item 24 | 0.624121 | 0.548424 |

| Item 27 | 0.634628 | 0.615322 |

| Item 28 | 0.650901 | 0.646807 |

| Item 29 | 0.678309 | 0.707136 |

| Item 30 | 0.634317 | 0.545270 |

| Item 32 | 0.694594 | 0.813322 |

| Item 33 | 0.646605 | 0.603532 |

| Item 34 | 0.560207 | 0.503846 |

| Item 35 | 0.541053 | 0.419253 |

| Item 36 | 0.674527 | 0.635340 |

| Item 6 LOG10 | 0.452276 | 0.465147 |

| Item 7 SQRT | 0.627467 | 0.566931 |

| Item 8 | 0.575014 | 0.536214 |

| Item 14 SQRT | 0.550560 | 0.494345 |

| Item 16 LOG10 | 0.347056 | 0.318866 |

| Item 17 LOG10 | 0.434958 | 0.392678 |

| Item 19 LOG10 | 0.406978 | 0.310654 |

| Item 25 | 0.523640 | 0.543393 |

| Item 26 LOG10 | 0.429725 | 0.398306 |

| Item 31 | 0.604590 | 0.585158 |

References

- Stephenson, N. Snow Crash, 1st ed.; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.-M.; Kim, Y.-G. A Metaverse: Taxonomy, Components, Applications, and Open Challenges. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 4209–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Pereira, V.; Sánchez-Amboage, E.; Membiela-Pollán, M. Facing the challenges of metaverse: A systematic literature review from Social Sciences and Marketing and Communication. Prof. Inf. 2023, 32, e320102. Available online: https://revista.profesionaldelainformacion.com/index.php/EPI/article/view/87104/63308 (accessed on 23 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bojic, L. Metaverse through the prism of power and addiction: What will happen when the virtual world becomes more attractive than reality? Eur. J. Futures Res. 2022, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, R.; Yang, Y.; Xue, X.; Chen, S. Metaverse: Perspectives from graphics, interactions and visualization. Vis. Inf. 2022, 6, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Hu, L.; Wang, Y. The metaverse in education: Definition, framework, features, potential applications, challenges, and future research topics. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1016300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethcle, N.; Weinberger, M. Applying the Metaverse to Real-world Citizen Participation—First Results from a Field Experiment. In Proceedings of the 58th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Fajardo, V.; Puig-Cabrera, M.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, I. Beyond the real world: Metaverse adoption patterns in tourism among Gen Z and Millennials. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 28, 1261–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. What Is Gen Z? Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-gen-z (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Zelazko, A. Millenial, Demographic Group. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/millennial (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Shahzad, K.; Ashfaq, M.; Zafar, A.U.; Basahel, S. Is the future of the metaverse bleak or bright? Role of realism, facilitators, and inhibitors in metaverse adoption. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 209, 123768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Kowalski, R.; Achuthan, K. Metaverse technologies and human behavior: Insights into engagement, adoption, and ethical challenges. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2025, 19, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottura, S. Does Anyone Care about the Opinion of People on Participating in a “Social” Metaverse? A Review and a Draft Proposal for a Surveying Tool. Future Internet 2024, 16, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerberg, M. The Metaverse and How We Will Build It Together. Connect 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uvufun6xer8 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Babu, A.; Mohan, P. Impact of the Metaverse on the Digital Future: People’s Perspective. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems, Coimbatore, India, 22–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Rosen, M.A.; Yáñez, J.A. Social Cognitive Theory to Assess the Intention to Participate in the Facebook Metaverse by Citizens in Peru during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, A.S.; Ghorpade, N.; Hashim, M.F.; Vaishnav, J.; Almaspoor, Z. A Comprehensive Study on Metaverse and Its Impacts on Humans. Adv. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 2022, 3247060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Allam, Z. The Metaverse as a virtual form of data-driven smart cities: The ethics of the hyper-connectivity, datafication, algorithmization, and platformization of urban society. Comput. Urban Sci. 2022, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in psychobiologic functioning. In Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action; Hemisphere Publishing Corp.: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 355–394. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, J. Metaverse-Statistics & Facts. 10 January 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/8652/metaverse/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Dixon, S.J. Share of Adults in the United States Who Are Interested in Meta’s New Virtual Reality Project Known as the Metaverse as of November 2021. 21 February 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1277855/united-statesadults-interested-meta-metaverse/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Petrosyan, A. Feelings Toward the Metaverse According to Adults in the United States as of January 2022. 7 July 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1290667/united-states-adults-feelings-toward-metaverse/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Petrosyan, A. Views on the Metaverse According to Adults in the United States as of January 2022. 7 July 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1290435/united-states-adults-views-of-metaverse/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Dixon, S.J. Share of Adults in the United States Joining or Considering Joining the Metaverse for Various Reasons as of December 2021. 7 February 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1288048/united-states-adults-reasons-forjoining-the-metaverse/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Web of Science. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Scopus. Available online: https://www.scopus.com (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Qiu, H.; Hoe-Lian, G.D.; Ong, A.; Jin, S.; Wang, S. Why Social Media Users Are Hesitant to Embrace the Metaverse: Technology Acceptance, Perceived Risks and Mitigations. In Proceedings of the HCI International 2024, Washington, DC, USA, 29 June–4 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragha, P.; Dhalmahapatra, K.; Natarajan, T. The future of human experience: The drivers of user adoption of the metaverse. Online Inf. Rev. 2025, 49, 669–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Yu, Z. Investigating Users’ Acceptance of the Metaverse with an Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 40, 5810–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, O.; Zallio, M.; Schnitzer, B. Young skeptics: Exploring the perceptions of virtual worlds and the metaverse in generations Y and Z. Front. Virtual Real. 2024, 5, 1330358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiale, Z.; Farzana, Q.; Jihad, M. Embracing the new reality: Gen Y’s intention to use metaverse apps and devices. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 398–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Ph. D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/15192 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environment Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Krahn, H.J.; Galambos, N.L. Work values and beliefs of ‘Generation X’ and ‘Generation Y’. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 17, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Forms. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/online-surveys-polls-quizzes (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Digital 2024: Italy. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-italy (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis, 1st ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.W. On factors and factors scores. Psichometrika 1967, 32, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, R.L. Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, MI, USA; Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Reio, T.G.; Shuck, B. Exploratory Factor Analysis: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2014, 17, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM SPSS Statistics. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Gensler, S.; Weiber, R.; Weiber, T. Factor Analysis. In Multivariate Analysis, 1st ed.; Roscher, B., Ed.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; pp. 381–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, A.; Molino, D. Factor Analysis for Social Sciences, 1st ed.; Research Notebooks Series, A14-400/12; Social Sciences Dept., University of Turin: Torino, Italy, 2011. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R.H. Confirmatory Factor Analysis. In Handbook of Applied Multivariate Statistics and Mathematical Modeling; Tinsley, H.E.A., Brown, S.D., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 465–497. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, M.S. The effect of standardization on a Chi-square approximation in factor analysis. Biometrika 1951, 38, 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziuban, C.D.; Shirkey, E.C. When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Some decision rules. Psychol. Bull. 1974, 81, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Factor Analysis Descriptives. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/30.0.0?topic=analysis-factor-descriptives (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- McDonald, R.P. Factor Analysis and Related Methods, 1st ed.; Psychology Press, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1990, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models, 1st ed.; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W. An Overview of Analytic Rotation in Exploratory Factor Analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2001, 36, 111–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurstone, L.L. Multiple Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga, M. How to Factor-Analyze Your Data Right: Do’s, Don’ts, and How-To’s. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2010, 3, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.C. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R.; Revicki, D.A. Reliability and validity (including responsiveness). In Assessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials: Methods and Practice, 2nd ed.; Fayers, P., Hays, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gail, M.S.; Artino, A.R., Jr. Analyzing and Interpreting Data from Likert-Type Scales. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, S. Likert scales: How to (ab)use them. Med. Educ. 2004, 38, 1217–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoff, N. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBMS SPSS Amos. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/it-it/products/structural-equation-modeling-sem (accessed on 12 November 2025).

| Tag Ti—Represented Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| T1—New social platform | The metaverse will be the new platform for new social media. |

| T2—Flooding mobile phones and devices | The metaverse will run on as many devices as possible—smartphones, tablets, headsets, computers and other smart devices. |

| T3—New internet | The metaverse will be the new Internet with infrastructure of contents. |

| T4—Doing activities of daily living | People can carry out (or are “encouraged” to) the usual activities of their life in the metaverse. |

| T5—People meet actively/share experiences | People, with particular attention to relatives and friends, meet in the metaverse and together they carry out actions and/or share experiences (depending on the specific context, this may evoke—also implicitly—no need to do so in reality). |

| T6—Tearing down the boundaries | The metaverse allows people to do anything by tearing down the boundaries/barriers/limits of reality (depending on the specific context, this may also be implicit). |

| T7—Living life in the metaverse | People can perform/transfer actions typical of real life to the metaverse. |

| Extracted Factors | % of Residuals < 0.1 (Absolute Value) | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 96.37 | 0.049 |

| 5 | 98.79 | 0.038 |

| 6 | 99.39 | 0.031 |

| No. of Extracted Factors | Type of Rotation | Criterion (Ci) Giving the Best Result | Discarded Factors (Fi) | No. of Factors Left | Cumulated Explained Total Variance (%) Fact. Left (All Fact.) | Loading Cutoff (Absolute Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Ortho | C2 | - | 4 | 47.37 (54.29) | 0.463 |

| 4 | Oblimin | C2 | - | 4 | 47.37 (54.29) | 0.433 |

| 4 | Promax | C2 | - | 4 | 47.37 (54.29) | 0.459 |

| 4 | Promax | C4 | F4 | 3 | 44.67 (49.83) | 0.501 |

| 5 | Ortho | C2 | F5 | 4 | 48.00 (54.29) | 0.507 |

| 5 | Oblimin | C2 | F4 | 4 | 47.59 (53.66) | 0.403 |

| 5 | Promax | C2 | F5 | 4 | 48.00 (54.29) | 0.544 |

| 5 * | Promax | C4 | F5 | 4 | 48.00 (54.29) | 0.518 |

| 6 | Ortho | C2 | F5, F6 | 4 | 48.15 (54.29) | 0.423 |

| 6 | Oblimin | C2 | F1 | 5 | 40.56 (23.54) | 0.386 |

| 6 | Promax | C2 | F6 | 5 | 51.16 (58.11) | 0.373 |

| 6 | Promax | C4 | F5, F6 | 4 | 48.15 (54.29) | 0.594 |

| Scale Item No. | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 I think that, in virtual social worlds, doing what I want and sharing my experiences can better my well-being (+) (9) (T6) | 0.591 | |||

| 2 If there was something limiting my life, I think I could overcome it by getting immersed in virtual social worlds and attending experiences that I would select myself (+) (11) (T7) | 0.898 | |||

| 3 If I had trouble travelling, being able to meet up anyway with people in virtual social worlds would be consolatory for me (+) (23) (T6) | 0.838 | |||

| 4 Doing things in virtual social worlds rather than in reality can be positive (+) (34) (T7) | 0.518 | |||

| 5 * I am afraid that social relations made by users interacting in virtual social worlds might impoverish people (−) (6) (T7) | 0.717 | |||

| 6 * I don’t like the idea of “being away” from reality around me while immersed in virtual social worlds (−) (17) (T7) | 0.778 | |||

| 7 * In my opinion the experiences and sharing in virtual social worlds will not be as satisfying as experiences and sharing in real life (−) (19) (T7) | 0.587 | |||

| 8 * I wouldn’t like to wear all the time on the head a display device for getting immersed in virtual social worlds (−) (26) (T7) | 0.706 | |||

| 9 In virtual social worlds, I would like to attend public events and situations, such as going to concerts, to cinema, to theater, to club (+) (21) (T4) | 0.775 | |||

| 10 I think that attending public entertainment events within virtual social worlds is a good idea because I can have fun and feel at peace (+) (33) (T4) | 0.710 | |||

| 11 I would like to participate in astonishing events within virtual social worlds, like for example attending concerts in between the planets, or going to amusement parks stretching to the horizon, or shopping in ancient Rome (+) (35) (T7) | 0.642 | |||

| 12 I think I will use the virtual social worlds (+) (36) (T7) | 0.544 | |||

| 13 Doing fitness while immersed in virtual scenarios draws me (+) (1) (T7) | 0.671 | |||

| 14 The possibility to play sports and games within virtual social worlds with other people “present” in virtual, is a nice thing (+) (29) (T4) | 0.800 | |||

| 15 Playing sports within virtual social worlds is an interesting thing (+) (32) (T4) | 0.975 |

| Question From Literature Reporting the Selection of a “Negative” Answer | Items of F2 |

|---|---|

| In [16], the question “Can Metaverse be a world where the digital world is more valuable than the physical world?” (28.6% = “Yes”, 37.7% = “No”, 33.6% = “Not Sure”) has a relevant percentage of “No” (it is a “negative” answer). | Item 5—I am afraid that social relations made by users interacting in virtual social worlds might impoverish people. (Agree 36.4% + Strongly agree 43.5% = 79.9%) Item 6—I don’t like the idea of “being away” from reality around me while immersed in virtual social worlds. (Agree 40.8% + Strongly agree 38% = 78.8%) Item 7—In my opinion the experiences and sharing in virtual social worlds can’t be as satisfying as experiences and sharing in real life. (Agree 33.7% + Strongly agree 47.8% = 81.5%) Item 8—I wouldn’t like to wear all the time on the head a display device for getting immersed in virtual social worlds. (Agree 35.3% + Strongly agree 45.7% = 81%) |

| In [18], the question “Do you think a Metaverse could create a physical communication gap between humans, and also cause hindrance in physical relationships?” (47.4% = “Yes”, 14.3% = “No”, 38.2% = “Maybe”) has a relevant percentage of “Yes” (it is a “negative” answer). | |

| In [19], the question “In the Metaverse, you could do many of the things you do now such as socialize with others, play games, watch concerts, and shop for digital and non-digital items such as clothing, home goods, and cars. Which of the following describe your views on Metaverse? — Select all that apply” has a relevant percentage in the answer “Not good as real life” = 30% (it is a “negative” answer). Note: all available answers have not been reported, because the list is too long. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mottura, S.; Mondellini, M. A Proposal of a Scale to Evaluate Attitudes of People Towards a Social Metaverse. Future Internet 2025, 17, 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120556

Mottura S, Mondellini M. A Proposal of a Scale to Evaluate Attitudes of People Towards a Social Metaverse. Future Internet. 2025; 17(12):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120556

Chicago/Turabian StyleMottura, Stefano, and Marta Mondellini. 2025. "A Proposal of a Scale to Evaluate Attitudes of People Towards a Social Metaverse" Future Internet 17, no. 12: 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120556

APA StyleMottura, S., & Mondellini, M. (2025). A Proposal of a Scale to Evaluate Attitudes of People Towards a Social Metaverse. Future Internet, 17(12), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120556