Machine Learning Pipeline for Early Diabetes Detection: A Comparative Study with Explainable AI

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

1.2. Research Objective

1.3. Novelty and Significant Contributions

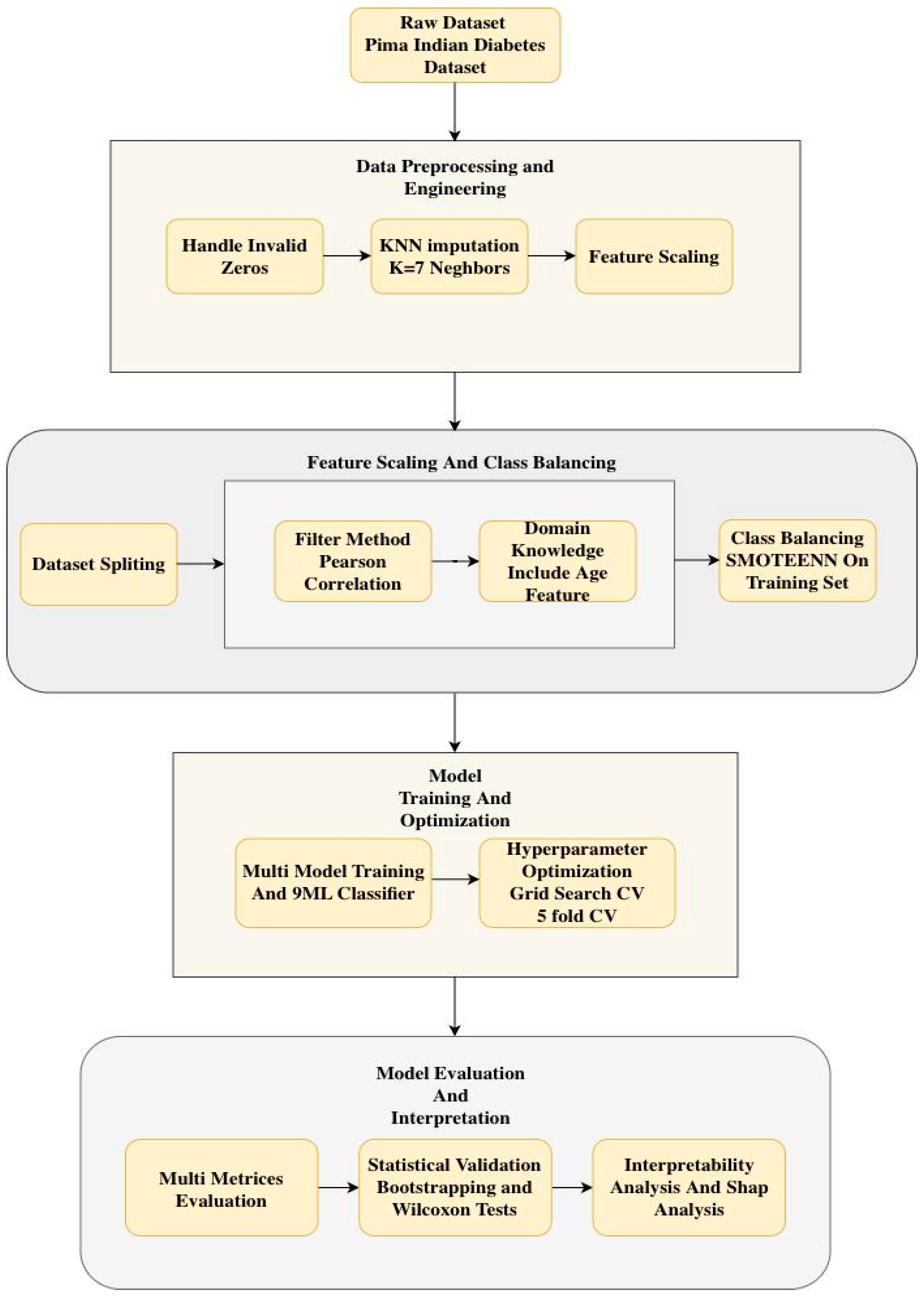

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

- Pregnancies: Number of times pregnant.

- Glucose: Plasma glucose concentration 2 h in an oral glucose tolerance test (mg/dL).

- BloodPressure: Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg).

- SkinThickness: Triceps skin fold thickness (mm), a measure of subcutaneous body fat.

- Insulin: 2-h serum insulin (mu U/mL).

- BMI: Body Mass Index (weight in kg/(height in m)2), a measure of body fat based on height and weight.

- DiabetesPedigreeFunction: A score that indicates the likelihood of diabetes based on family history.

- Age: Age in years (all patients are at least 21 years old).

- Outcome: Target variable (0 = no diabetes, 1 = diabetes).

| Feature | Description | Unit | Count | Mean | Std Dev | Min | 50% (Median) | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancies | Number of times pregnant | - | 768 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 0 | 3 | 17 |

| Glucose | Plasma glucose concentration | mg/dL | 768 | 120.9 | 32.0 | 0 | 117.0 | 199 |

| BloodPressure | Diastolic blood pressure | mm Hg | 768 | 69.1 | 19.4 | 0 | 72.0 | 122 |

| SkinThickness | Triceps skin fold thickness | mm | 768 | 20.5 | 16.0 | 0 | 23.0 | 99 |

| Insulin | 2 h serum insulin | mu U/mL | 768 | 79.8 | 115.2 | 0 | 30.5 | 846 |

| BMI | Body Mass Index | kg/m2 | 768 | 32.0 | 7.9 | 0 | 32.0 | 67.1 |

| DiabetesPedigreeFunction | Diabetes likelihood score | - | 768 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.078 | 0.3725 | 2.42 |

| Age | Age | Years | 768 | 33.2 | 11.8 | 21 | 29.0 | 81 |

| Outcome | Target Variable | 0 or 1 | 768 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

2.2. Input Variables

2.3. Data Preprocessing

- Handling of Invalid Zero Values: The features Glucose, Blood Pressure, Skin Thickness, Insulin, and BMI contained biologically implausible zero values, such as zero blood pressure. These values were treated as missing data (NaN) rather than valid measurements to prevent model bias.

- KNN Imputation: Missing values were imputed by the KNN Imputation algorithm with 7 neighbors, which provides a balance between using too few neighbors, which can lead to noisy imputations, and too many, which can oversmooth and ignore local patterns. This is the method used over mean or median imputation as it maintains the underlying data distribution and pattern of covariance by filling in missing values based on the similarity of features of the nearest neighbors. Table 2 shows the statistics dataset after KNN imputation.

2.4. Dataset Splitting

2.5. Feature Engineering

2.6. Feature Selection

- -

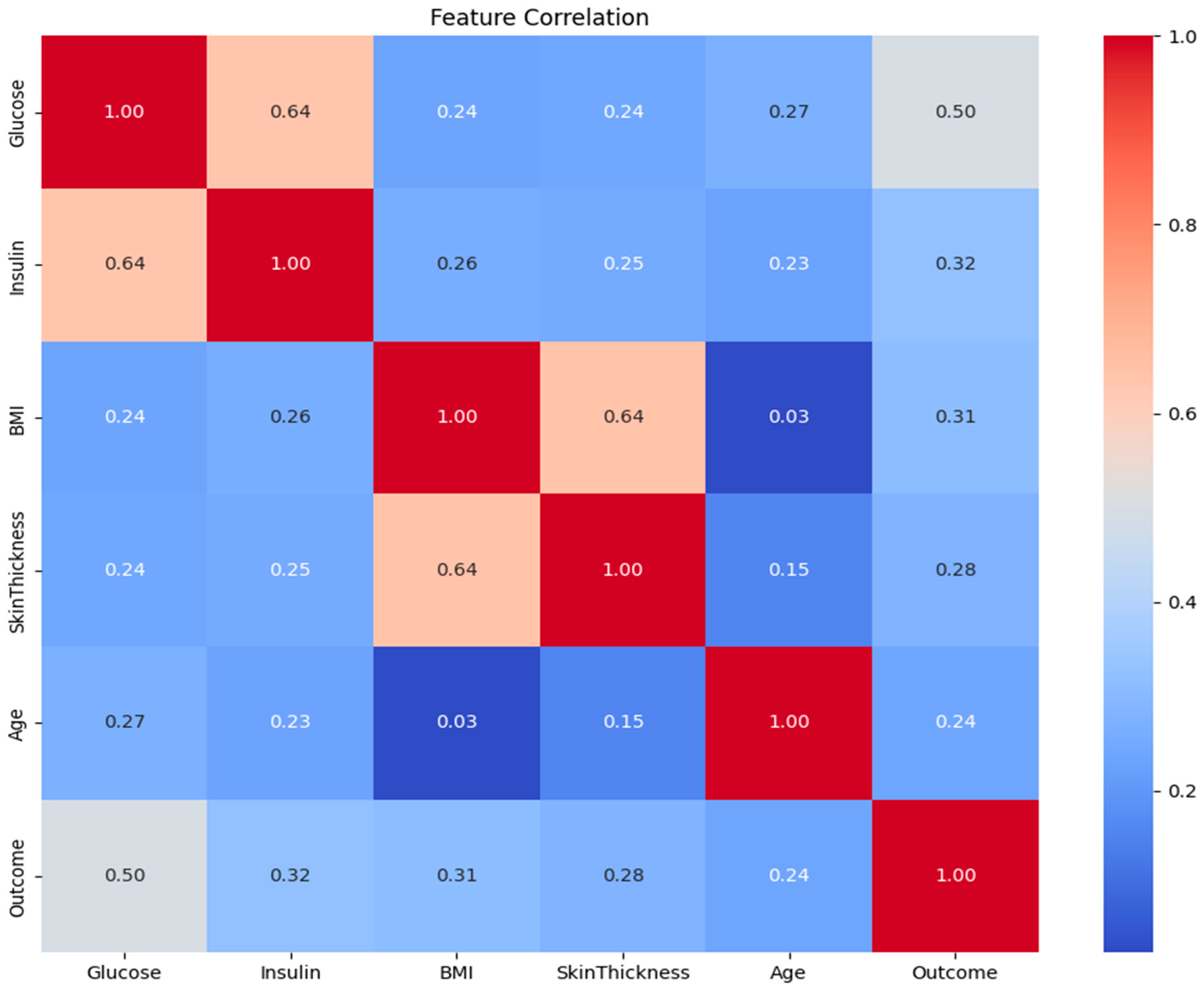

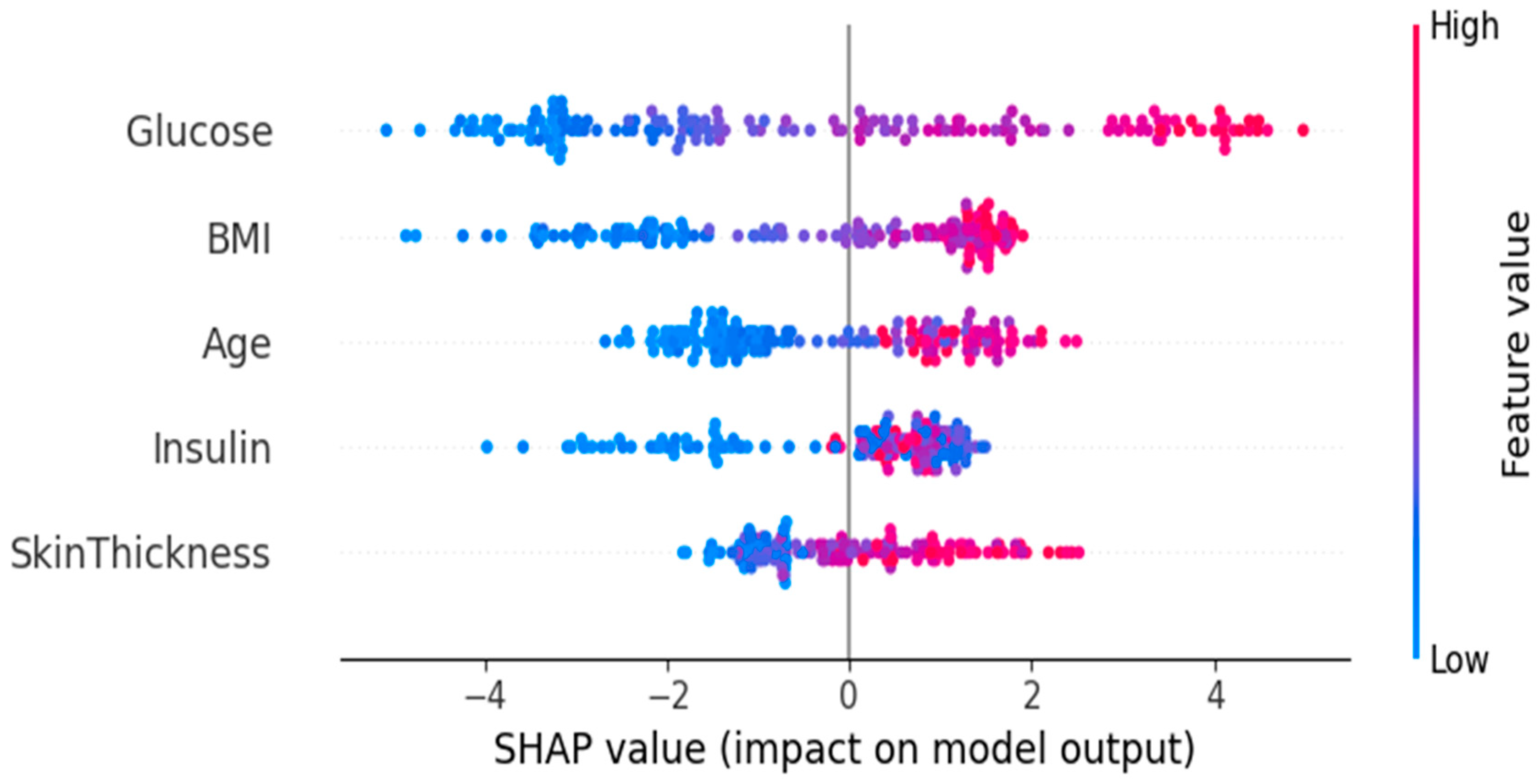

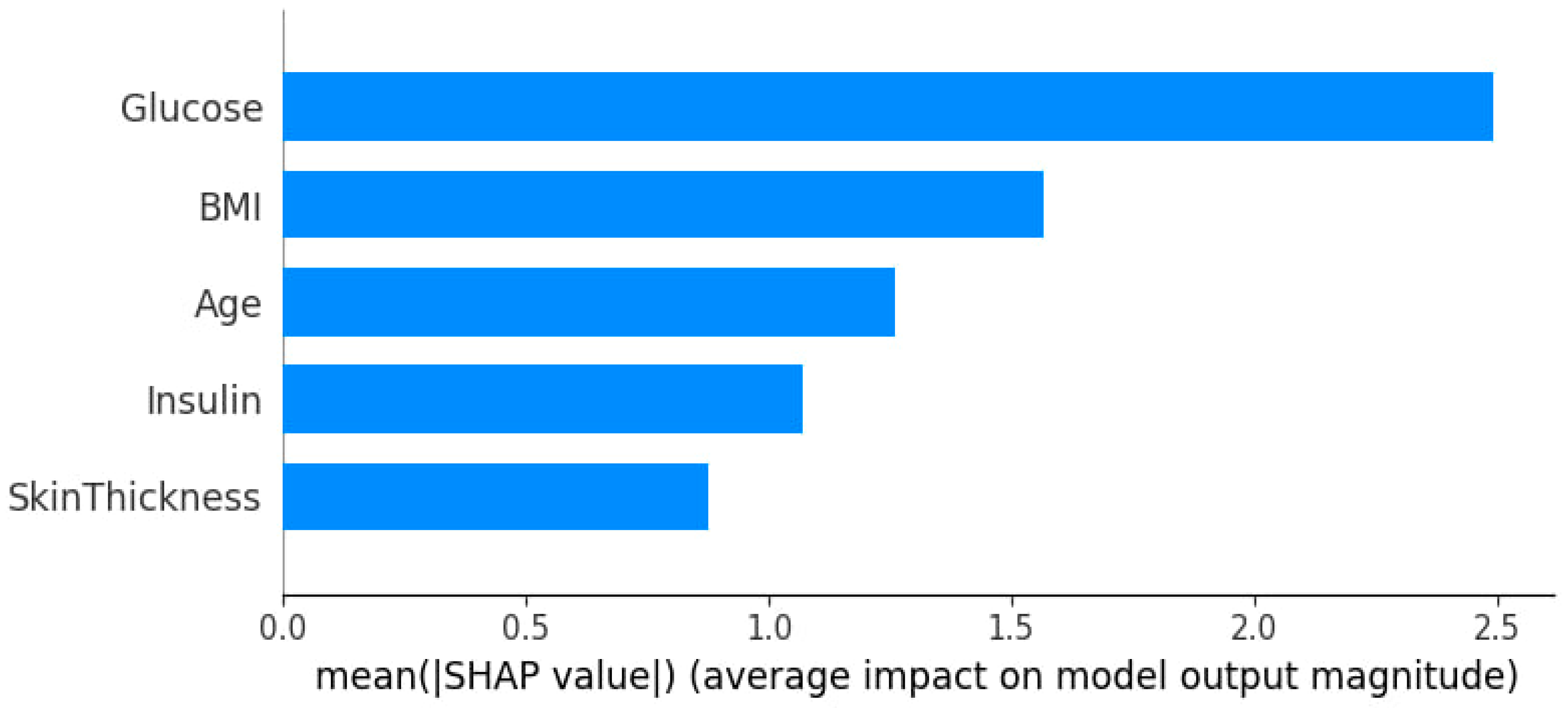

- Pearson Correlation Filtering: The absolute value of the correlation coefficient of each feature with the target (Outcome) was calculated. The most correlated features, N = 4, were selected. N = 4 is quantitatively determined by comparison among Pearson correlation coefficients for each of the features and the target variable. The top four features with the highest absolute Pearson correlation to the Outcome were selected: Glucose, BMI, Insulin, and Diabetes Pedigree Function. Based on its established clinical importance, Age was also added to the final set. Thus, the five features used for model development were: Glucose, BMI, Insulin, Diabetes Pedigree Function, and Age.

- -

- Domain Knowledge Integration: As it had clinically validated relevance, Age was included in the final set of features by design, although it was not among the top N features.

2.7. Handling Class Imbalance

2.8. Model Development

- Ensemble/Boosting: XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, AdaBoost, GB

- Tree-based: Balanced RF

- Kernel-based: SVM

- Distance-based: KNN

- Linear: LR

2.9. Hyperparameter Tuning

2.10. Model Performance Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

| Model | ROC AUC | PR AUC | Precision | Recall | F1 | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.956 | 0.987 | 0.971 | 0.968 |

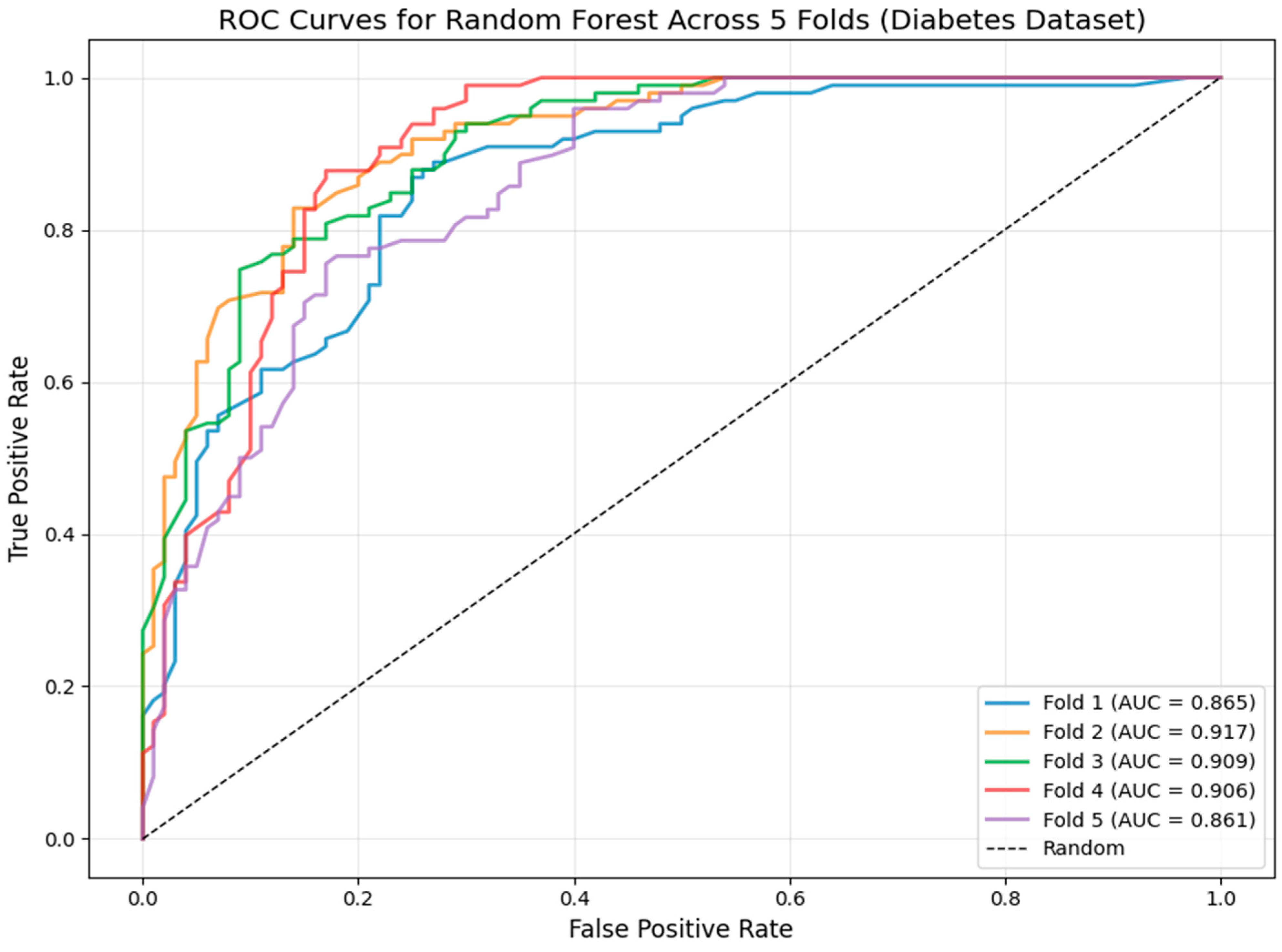

| RF | 0.971 | 0.972 | 0.962 | 0.954 | 0.958 | 0.955 |

| KNN | 0.971 | 0.968 | 0.982 | 0.921 | 0.951 | 0.948 |

| LightGBM | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.955 |

| XGBoost | 0.966 | 0.967 | 0.962 | 0.950 | 0.956 | 0.953 |

| SVM | 0.963 | 0.960 | 0.944 | 0.971 | 0.957 | 0.953 |

| AdaBoost | 0.962 | 0.964 | 0.942 | 0.942 | 0.942 | 0.937 |

| GB | 0.961 | 0.962 | 0.946 | 0.942 | 0.944 | 0.939 |

| LR | 0.951 | 0.955 | 0.872 | 0.983 | 0.924 | 0.912 |

| LASSO | 0.951 | 0.956 | 0.875 | 0.983 | 0.926 | 0.915 |

| Model | ROC AUC | PR AUC | Precision | Recall | F1 | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 0.835 | 0.729 | 0.691 | 0.658 | 0.674 | 0.778 |

| GB | 0.825 | 0.688 | 0.613 | 0.785 | 0.688 | 0.752 |

| CatBoost | 0.825 | 0.695 | 0.574 | 0.827 | 0.678 | 0.726 |

| AdaBoost | 0.822 | 0.689 | 0.612 | 0.738 | 0.669 | 0.745 |

| RF | 0.822 | 0.688 | 0.597 | 0.775 | 0.674 | 0.739 |

| SVM | 0.811 | 0.683 | 0.648 | 0.766 | 0.702 | 0.773 |

| KNN | 0.799 | 0.642 | 0.687 | 0.617 | 0.650 | 0.768 |

| LightGBM | 0.795 | 0.649 | 0.603 | 0.747 | 0.668 | 0.741 |

| XGBoost | 0.775 | 0.648 | 0.578 | 0.743 | 0.650 | 0.721 |

3.1. Feature Correlation Analysis

3.2. Model Robustness: Cross-Validation ROC Analysis

3.3. Feature Importance and Impact via SHAP Analysis

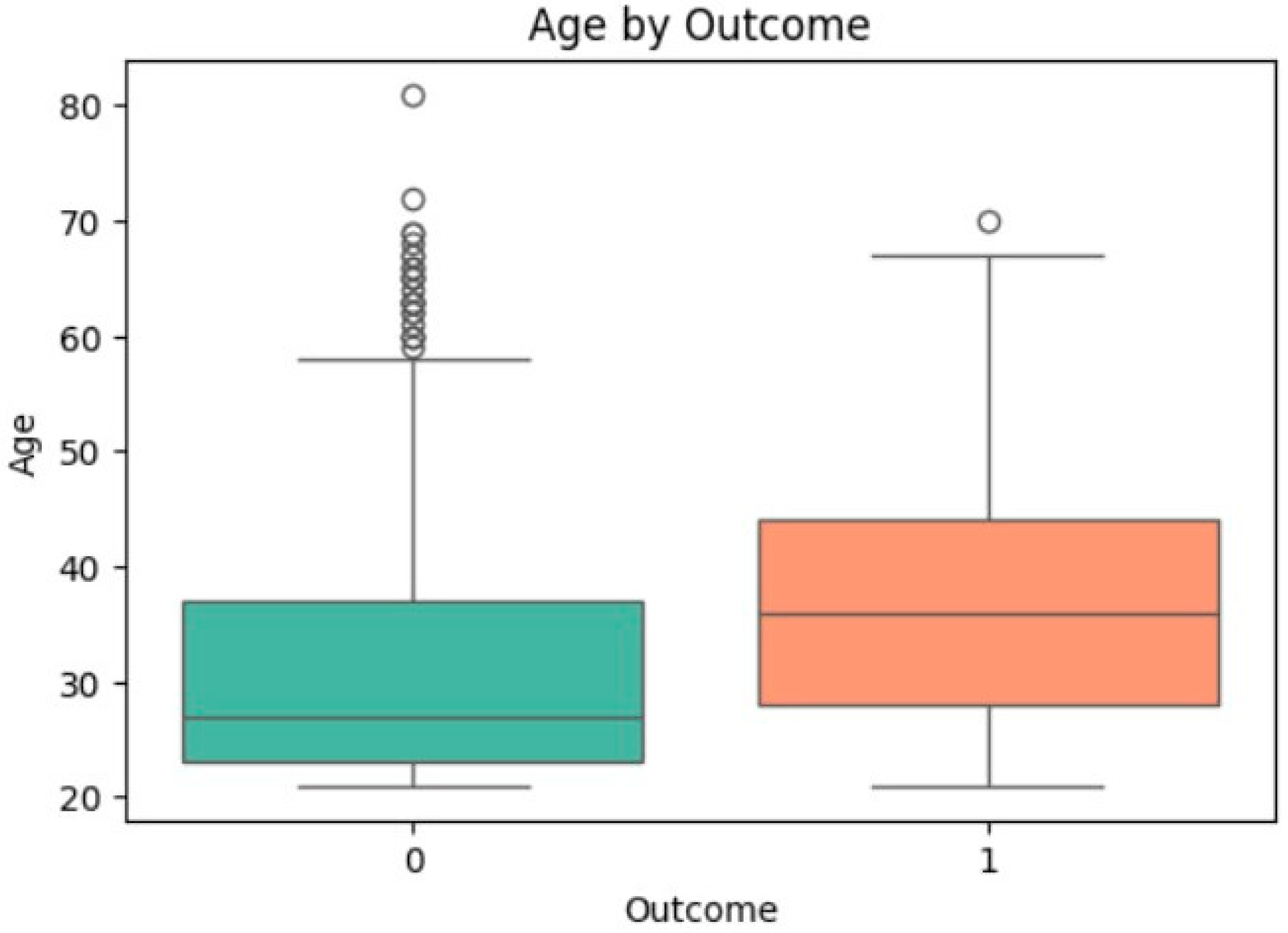

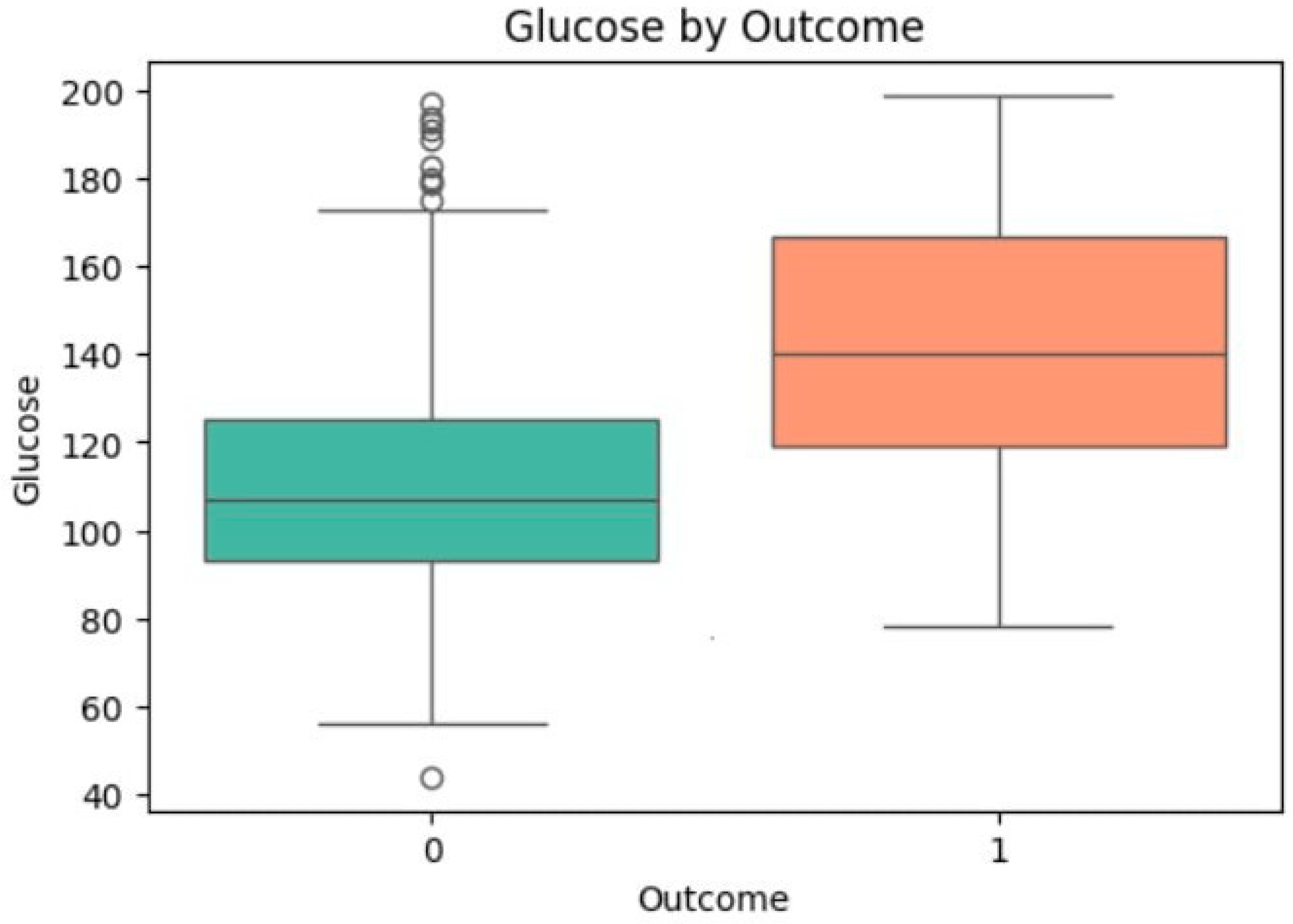

3.4. Univariate Analysis of Feature Associations with Diabetes

| Feature | T-Statistic | p-Value (t-test) | Mean (Group 0) | Mean (Group 1) | Cohen’s d | Odds Ratio (OR) | 0.95 CI for OR | p-Value (Regression) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | −14.974 | <0.0001 | 110.57 | 142.24 | 1.195 | 1.042 | [1.035, 1.049] | <0.0001 |

| Insulin | −8.851 | <0.0001 | 129.89 | 195.29 | 0.712 | 1.008 | [1.006, 1.010] | <0.0001 |

| BMI | −9.097 | <0.0001 | 30.85 | 35.38 | 0.692 | 1.109 | [1.082, 1.136] | <0.0001 |

| SkinThickness | −8.037 | <0.0001 | 27.19 | 32.61 | 0.607 | 1.072 | [1.052, 1.092] | <0.0001 |

| Age | −6.921 | <0.0001 | 31.19 | 37.07 | 0.514 | 1.043 | [1.030, 1.056] | <0.0001 |

3.5. Comparative Model Performance and Statistical Validation

3.6. Clinical Translation and Actionable Insights

3.7. Multi-Dataset Generalizability Assessment

3.7.1. Validation Dataset 1: CDC BRFSS 2015 Dataset

3.7.2. Validation Dataset 2: Diabetes 130-US Hospitals Dataset

3.7.3. Cross-Dataset Performance Consistency

4. Conclusions

- External Validation: using larger, multi-ethnic, and more recent datasets to validate robustness and generalizability.

- Multi-Modal Data Integration: developing the model by integrating other data types, such as medical images or textual data.

- Real-Time Deployment: Implementing a real-time web service or mobile application within an IoT-enabled healthcare framework.

- Advanced Explainability: Using other explainable AI methods to provide case-based explanations for clinicians.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, Z.; Mohamed, K.; Zeeshan, S.; Dong, X. Artificial intelligence with a multi-functional machine learning platform development for better healthcare and precision medicine. Database 2020, 2020, baaa010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballé-Cervigón, N.; Castillo-Sequera, J.L.; Gómez-Pulido, J.A.; Gómez-Pulido, J.M.; Polo-Luque, M.L. Machine learning applied to diagnosis of human diseases: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standl, E.; Khunti, K.; Hansen, T.B.; Schnell, O. The global epidemics of diabetes in the 21st century: Current situation and perspectives. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, B.; Irshad, A.; Rida, I.; Shabaz, M. AI-driven predictive modeling for disease prevention and early detection. SLAS Technol. 2025, 31, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Kwon, S.; Lee, D. Predicting Infectious Disease Using Deep Learning and Big Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Asadi, S.; Abumalloh, R.A.; Samad, S.; Ghabban, F.; Supriyanto, E.; Osman, R. Sustainability performance assessment using self-organizing maps (SOM) and classification and ensembles of regression trees (CART). Sustainability 2021, 13, 3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, C.M.; Patel, P.; Ghetia, T.; Mazzeo, P.L. Effective heart disease prediction using machine learning techniques. Algorithms 2023, 16, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Haque, M.R.; Iqbal, H.; Hasan, M.M.; Hasan, M.; Kabir, M.N. Breast cancer prediction: A comparative study using machine learning techniques. SN Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, S.; Tanzeem, A.K.; Tasawar, I.K.; Shorna, F.; Siddique, M.A.B.; Alam, S.B. Blood cancer recognition based on discriminant gene expressions: A comparative analysis of optimized machine learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 12th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 27–30 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 0385–0391. [Google Scholar]

- Al Reshan, M.S.; Amin, S.; Zeb, M.A.; Sulaiman, A.; Alshahrani, H.; Shaikh, A. A robust heart disease prediction system using hybrid deep neural networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 121574–121591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, S.; Adhikari, M.; Balasubramanian, V.; Menon, V.G.; Li, X.; Zakarya, M. An intelligent heart disease prediction system based on swarm-artificial neural network. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 14723–14737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar Nia, N.; Kaplanoglu, E.; Nasab, A. Evaluation of artificial intelligence techniques in disease diagnosis and prediction. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2023, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kor, C.-T.; Li, Y.-R.; Lin, P.-R.; Lin, S.-H.; Wang, B.-Y.; Lin, C.-H. Explainable Machine Learning Model for Predicting First-Time Acute Exacerbation in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alex, S.A.; Nayahi, J.J.V.; Shine, H.; Gopirekha, V. Deep convolutional neural network for diabetes mellitus prediction. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jerjawi, N.S.; Abu-Naser, S.S. Diabetes prediction using artificial neural network. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 121, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bashbishy, A.E.S.; El-Bakry, H.M. Pediatric diabetes prediction using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhao, X.; Miao, C. A comprehensive exploration to the machine learning techniques for diabetes identification. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 4th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Singapore, 5–8 February 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Chandgude, N.; Pawar, S. Diagnosis of diabetes using Fuzzy inference System. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Computing Communication Control and Automation (ICCUBEA), Pune, India, 12–13 August 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, Y.; Gorelova, I.; Bellini, F.; D’ascenzo, F. Drinking water quality assessment using a fuzzy inference system method: A case study of Rome (Italy). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegar, Y.; Barzegar, A.; Bellini, F.; Marrone, S.; Verde, L. Fuzzy inference system for risk assessment of wheat flour product manufacturing systems. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 4431–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, F.; Barzegar, Y.; Barzegar, A.; Marrone, S.; Verde, L.; Pisani, P. Sustainable water quality evaluation based on cohesive Mamdani and Sugeno fuzzy inference system in Tivoli (Italy). Sustainability 2025, 17, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, Y.; Barzegar, A.; Marrone, S.; Verde, L.; Bellini, F.; Pisani, P. Computational Risk Assessment in Water Distribution Network. In International Conference on Computational Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Barzegar, A.; Campanile, L.; Marrone, S.; Marulli, F.; Verde, L.; Mastroianni, M. Fuzzy-based severity evaluation in privacy problems: An application to healthcare. In Proceedings of the 2024 19th European Dependable Computing Conference (EDCC), Leuven, Belgium, 8–11 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Naseem, A.; Habib, R.; Naz, T.; Atif, M.; Arif, M.; Allaoua Chelloug, S. Novel Internet of Things based approach toward diabetes prediction using deep learning models. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 914106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Singh, S.; Prasad, D. Machine learning and IoT-based model for patient monitoring and early prediction of diabetes. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2022, 34, e7219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Z.; Luo, X.; Pei, J.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, Y. Data pricing in machine learning pipelines. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2022, 64, 1417–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, F.; Wever, M.; Tornede, A.; Hüllermeier, E. Predicting machine learning pipeline runtimes in the context of automated machine learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 3055–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.S.; Moore, J.H. TPOT: A tree-based pipeline optimization tool for automating machine learning. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Automatic Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 24 June 2016; PMLR: London, UK, 2016; pp. 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Baccouche, A.; Garcia-Zapirain, B.; Castillo Olea, C.; Elmaghraby, A. Ensemble deep learning models for heart disease classification: A case study from Mexico. Information 2020, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, J.B.; Nasien, D. Application of machine learning k-nearest neighbour algorithm to predict diabetes. Int. J. Electr. Energy Power Syst. Eng. 2023, 6, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, A.; Bulut, S. Machine learning for early diabetes screening: A comparative study of algorithmic approaches. Serbian J. Electr. Eng. 2025, 22, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.; Pourpanah, F.; Lim, C.P.; Wu, Q.M. Methods for class-imbalanced learning with support vector machines: A review and an empirical evaluation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.03398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. CatBoost for big data: An interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokker, C.; Abdelkader, W.; Bagheri, E.; Parrish, R.; Cotoi, C.; Navarro, T.; Germini, F.; Linkins, L.A.; Haynes, R.B.; Chu, L.; et al. Boosting efficiency in a clinical literature surveillance system with LightGBM. PLOS Digit. Health 2024, 3, e0000299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, A.; Katariya, R.; Patel, V. A review on random forest: An ensemble classifier. In International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 758–763. [Google Scholar]

- Theerthagiri, P.; Vidya, J. Cardiovascular disease prediction using recursive feature elimination and gradient boosting classification techniques. Expert Syst. 2022, 39, e13064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budholiya, K.; Shrivastava, S.K.; Sharma, V. An optimized XGBoost based diagnostic system for effective prediction of heart disease. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 4514–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asra, T.; Setiadi, A.; Safudin, M.; Lestari, E.W.; Hardi, N.; Alamsyah, D.P. Implementation of AdaBoost algorithm in prediction of chronic kidney disease. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Engineering, Applied Sciences and Technology (ICEAST), Pattaya, Thailand, 1–3 April 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 264–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ciu, T.; Oetama, R.S. Logistic regression prediction model for cardiovascular disease. IJNMT (Int. J. New Media Technol.) 2020, 7, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Haque, I.; Lu, H.; Moni, M.A.; Gide, E. Comparative performance analysis of K-nearest neighbour (KNN) algorithm and its different variants for disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, A.; Mustafa, W.; Marqas, R.B. A comparative study of diabetes detection using the Pima Indian diabetes database. Methods 2023, 7, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Salih, M.S.; Ibrahim, R.K.; Zeebaree, S.R.; Asaad, D.; Zebari, L.M.; Abdulkareem, N.M. Diabetic prediction based on machine learning using PIMA Indian dataset. Commun. Appl. Nonlinear Anal. 2024, 31, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoi, S.K.; Panda, S.K.; Jena, K.K.; Abhisekh, P.A.; Sahoo, K.S.; Sama, N.U.; Pradhan, S.S.; Sahoo, R.R. Prediction of diabetes in females of pima Indian heritage: A complete supervised learning approach. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 3074–3084. [Google Scholar]

- Shwartz-Ziv, R.; Armon, A. Tabular data: Deep learning is not all you need. Inf. Fusion 2022, 81, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinsztajn, L.; Oyallon, E.; Varoquaux, G. Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on typical tabular data? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 507–520. [Google Scholar]

- Esteva, A.; Robicquet, A.; Ramsundar, B.; Kuleshov, V.; DePristo, M.; Chou, K.; Cui, C.; Corrado, G.; Thrun, S.; Dean, J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Count | Mean | Std Dev | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 768 | 121.7 | 30.0 | 56.0 | 99.0 | 117.0 | 141.0 | 199.0 |

| BloodPressure | 768 | 71.3 | 12.4 | 38.0 | 64.0 | 72.0 | 80.0 | 122.0 |

| SkinThickness | 768 | 29.1 | 10.1 | 7.0 | 22.0 | 29.0 | 35.0 | 99.0 |

| Insulin | 768 | 155.1 | 100.2 | 15.0 | 87.0 | 130.5 | 200.0 | 744.0 |

| BMI | 768 | 32.5 | 6.8 | 18.2 | 28.0 | 32.0 | 36.6 | 67.1 |

| Feature | Stage | Count | Mean | Std Dev | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Before | 614 | 121.67 | 30.03 | 56.00 | 99.00 | 117.00 | 140.00 | 199.00 |

| Glucose | After | 448 | 126.61 | 34.06 | 56.00 | 100.00 | 120.00 | 156.26 | 199.00 |

| Insulin | Before | 614 | 149.36 | 89.75 | 15.00 | 87.00 | 135.00 | 187.25 | 744.00 |

| Insulin | After | 448 | 156.00 | 99.42 | 15.00 | 83.18 | 138.71 | 193.14 | 543.00 |

| BMI | Before | 614 | 32.43 | 6.83 | 18.20 | 27.62 | 32.40 | 36.50 | 67.10 |

| BMI | After | 448 | 33.23 | 7.79 | 18.20 | 27.78 | 32.80 | 37.50 | 67.10 |

| SkinThickness | Before | 614 | 29.05 | 9.34 | 7.00 | 23.00 | 29.00 | 34.54 | 99.00 |

| SkinThickness | After | 448 | 29.09 | 9.11 | 7.00 | 22.11 | 29.86 | 35.00 | 56.00 |

| Age | Before | 614 | 33.37 | 11.83 | 21.00 | 24.00 | 29.00 | 41.00 | 81.00 |

| Age | After | 448 | 32.32 | 10.50 | 21.00 | 24.00 | 29.00 | 40.00 | 72.00 |

| Model | Tuned Hyperparameters | Full Search Space | Final Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | n_estimators, max_depth, learning_rate, subsample | n_estimators: [100, 200, 500]; max_depth: [3, 6, 9]; learning_rate: [0.01, 0.1, 0.2]; subsample: [0.8, 1.0] | 200, 6, 0.1, 0.8 |

| CatBoost | iterations, depth, l2_leaf_reg | iterations: [500, 1000]; depth: [4, 6, 8]; l2_leaf_reg: [1, 3, 5] | 1000, 6, 3 |

| LightGBM | n_estimators, num_leaves, learning_rate | n_estimators: [100, 200, 500]; num_leaves: [15, 31, 63]; learning_rate: [0.01, 0.1, 0.2] | 200, 31, 0.1 |

| Random Forest (RF) | n_estimators, max_depth, min_samples_leaf | n_estimators: [100, 200, 500]; max_depth: [10, 20, None]; min_samples_leaf: [1, 2, 4] | 200, 20, 2 |

| SVM | C, gamma | C: [0.1, 1, 10, 100]; gamma: [‘scale’, ‘auto’, 0.1, 0.01] | 10, ‘scale’ |

| KNN | n_neighbors | n_neighbors: [3, 5, 7, 9, 11] | 7 |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | C, penalty | C: [0.1, 1, 10, 100]; penalty: [‘l2’] | 1, ‘l2’ |

| AdaBoost | n_estimators, learning_rate | n_estimators: [50, 100, 200]; learning_rate: [0.01, 0.1, 1.0] | 200, 0.1 |

| Gradient Boosting (GB) | n_estimators, learning_rate, max_depth | n_estimators: [100, 200, 500]; learning_rate: [0.01, 0.1, 0.2]; max_depth: [3, 4, 5] | 200, 0.1, 3 |

| Model | Dataset | ROC-AUC | Accuracy | F1-Score | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR (Baseline) | Pima | 0.851 | 0.779 | 0.675 | 0.872 | 0.983 |

| CatBoost (Proposed) | Pima | 0.972 | 0.968 | 0.971 | 0.956 | 0.987 |

| LSTM [41] | Pima | 0.890 | 0.850 | 0.800 | 0.820 | 0.780 |

| SVM with PCA [42] | Pima | 0.929 | 0.861 | 0.887 | 0.889 | 0.869 |

| LR [43] | Pima | 0.825 | 0.768 | 0.760 | 0.763 | 0.768 |

| ANN [24] | Kaggle | – | 0.680 | 0.590 | 0.660 | 0.560 |

| CNN [24] | Kaggle | – | 0.770 | 0.600 | 0.690 | 0.550 |

| LSTM [24] | Kaggle | – | 0.780 | 0.610 | 0.730 | 0.530 |

| Metric | k = 4 | k = 6 | k = 7 | k = 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 0.950 | 0.952 | 0.956 | 0.952 |

| Accuracy | 0.965 | 0.953 | 0.968 | 0.962 |

| Recall | 0.987 | 0.963 | 0.987 | 0.979 |

| F1-Score | 0.968 | 0.958 | 0.971 | 0.965 |

| ROC AUC | 0.971 | 0.969 | 0.972 | 0.969 |

| PR AUC | 0.972 | 0.971 | 0.972 | 0.969 |

| Model | ROC AUC | F1-Score | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 0.972 [0.965, 0.977] | 0.971 [0.955, 0.984] | 0.968 [0.953, 0.984] | 0.956 | 0.987 |

| RF | 0.971 [0.965, 0.976] | 0.959 [0.937, 0.976] | 0.955 [0.938, 0.973] | 0.963 | 0.955 |

| KNN | 0.971 [0.964, 0.977] | 0.951 [0.929, 0.969] | 0.949 [0.926, 0.969] | 0.982 | 0.922 |

| XGBoost | 0.966 [0.957, 0.974] | 0.957 [0.939, 0.973] | 0.953 [0.933, 0.971] | 0.963 | 0.951 |

| LightGBM | 0.966 [0.956, 0.975] | 0.959 [0.940, 0.975] | 0.955 [0.935, 0.975] | 0.959 | 0.959 |

| SVM | 0.963 [0.950, 0.973] | 0.958 [0.938, 0.975] | 0.953 [0.931, 0.973] | 0.944 | 0.971 |

| AdaBoost | 0.963 [0.953, 0.970] | 0.943 [0.920, 0.964] | 0.937 [0.915, 0.960] | 0.942 | 0.942 |

| GB | 0.961 [0.949, 0.971] | 0.944 [0.922, 0.964] | 0.940 [0.917, 0.960] | 0.946 | 0.942 |

| LR | 0.951 [0.939, 0.962] | 0.925 [0.900, 0.948] | 0.913 [0.884, 0.938] | 0.872 | 0.984 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | ROC AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 0.910 | 0.953 | 0.862 | 0.905 | 0.967 |

| XGBoost | 0.910 | 0.954 | 0.861 | 0.905 | 0.967 |

| LightGBM | 0.907 | 0.939 | 0.871 | 0.904 | 0.967 |

| GradientBoost | 0.892 | 0.908 | 0.872 | 0.890 | 0.961 |

| AdaBoost | 0.851 | 0.840 | 0.868 | 0.854 | 0.936 |

| RandomForest | 0.843 | 0.822 | 0.875 | 0.848 | 0.923 |

| KNN | 0.809 | 0.745 | 0.939 | 0.831 | 0.897 |

| SVM | 0.811 | 0.793 | 0.842 | 0.817 | 0.887 |

| LogisticRegression | 0.757 | 0.743 | 0.785 | 0.763 | 0.832 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | ROC AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LightGBM | 0.933 | 0.994 | 0.871 | 0.928 | 0.959 |

| XGBoost | 0.932 | 0.987 | 0.875 | 0.928 | 0.957 |

| CatBoost | 0.931 | 0.989 | 0.868 | 0.926 | 0.955 |

| RandomForest | 0.865 | 0.886 | 0.839 | 0.862 | 0.933 |

| LogisticRegression | 0.606 | 0.610 | 0.588 | 0.599 | 0.650 |

| Dataset | Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | ROC AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pima Indian | CatBoost | 0.968 | 0.956 | 0.987 | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| Pima Indian | XGBoost | 0.953 | 0.962 | 0.950 | 0.956 | 0.966 |

| Pima Indian | LightGBM | 0.955 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.966 |

| CDC BRFSS 2015 | CatBoost | 0.910 | 0.953 | 0.862 | 0.905 | 0.967 |

| CDC BRFSS 2015 | XGBoost | 0.910 | 0.953 | 0.861 | 0.905 | 0.967 |

| CDC BRFSS 2015 | LightGBM | 0.907 | 0.939 | 0.871 | 0.904 | 0.967 |

| Diabetes 130-US Hospitals | CatBoost | 0.931 | 0.989 | 0.868 | 0.926 | 0.955 |

| Diabetes 130-US Hospitals | XGBoost | 0.932 | 0.987 | 0.875 | 0.928 | 0.957 |

| Diabetes 130-US Hospitals | LightGBM | 0.933 | 0.989 | 0.871 | 0.928 | 0.959 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barzegar, Y.; Barzegar, A.; Bellini, F.; D'Ascenzo, F.; Gorelova, I.; Pisani, P. Machine Learning Pipeline for Early Diabetes Detection: A Comparative Study with Explainable AI. Future Internet 2025, 17, 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17110513

Barzegar Y, Barzegar A, Bellini F, D'Ascenzo F, Gorelova I, Pisani P. Machine Learning Pipeline for Early Diabetes Detection: A Comparative Study with Explainable AI. Future Internet. 2025; 17(11):513. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17110513

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarzegar, Yas, Atrin Barzegar, Francesco Bellini, Fabrizio D'Ascenzo, Irina Gorelova, and Patrizio Pisani. 2025. "Machine Learning Pipeline for Early Diabetes Detection: A Comparative Study with Explainable AI" Future Internet 17, no. 11: 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17110513

APA StyleBarzegar, Y., Barzegar, A., Bellini, F., D'Ascenzo, F., Gorelova, I., & Pisani, P. (2025). Machine Learning Pipeline for Early Diabetes Detection: A Comparative Study with Explainable AI. Future Internet, 17(11), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17110513