Abstract

Botnet attacks on Internet of Things (IoT) devices are escalating at the 5G/6G multi-access edge, yet most federated learning frameworks for IoT malware detection (FL-IMD) still hinge on a central aggregator, enlarging the attack surface, weakening privacy, and creating a single point of failure. We propose a two-tier, fully decentralized FL architecture aligned with MEC’s Proximal Edge Server (PES)/Supplementary Edge Server (SES) hierarchy. PES nodes train locally and encrypt updates with the Cheon–Kim–Kim–Song (CKKS) scheme; SES nodes verify ECDSA-signed provenance, homomorphically aggregate ciphertexts, and finalize each round via an Algorand-style committee that writes a compact, tamper-evident record (update digests/URIs and a global-model hash) to an append-only ledger. Using the N-BaIoT benchmark with an unsupervised autoencoder, we evaluate known-device and leave-one-device-out regimes against a classical centralized baseline and a cryptographically hardened but server-centric variant. With the heavier CKKS profile, attack sensitivity is preserved (TPR ), and specificity (TNR) declines by only 0.20 percentage points relative to plaintext in both regimes; a lighter profile maintains TPR while trading 3.5–4.8 percentage points of TNR for about 71% smaller payloads. Decentralization adds only a negligible per-round overhead for committee finality, while homomorphic aggregation dominates latency. Overall, our FL-IMD design removes the trusted aggregator and provides verifiable, ledger-backed provenance suitable for trustless MEC deployments.

1. Introduction

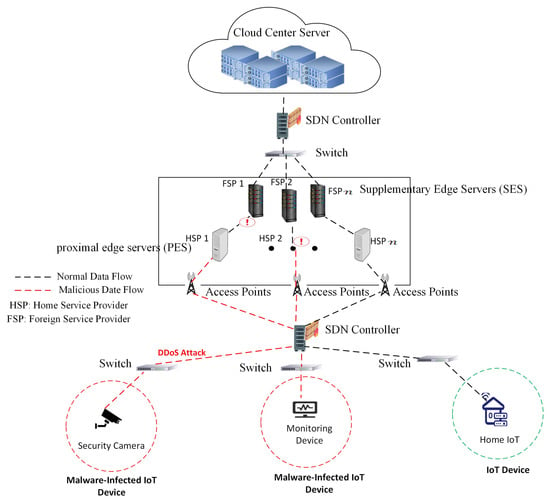

Botnet campaigns that weaponize Internet of Things (IoT) devices continue to escalate, particularly across 5G/6G Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC) infrastructures. This surge has made IoT security a first-order concern [1,2]. The 2025 SonicWall Cyber-Threat Report notes a 124% year-over-year increase in IoT attacks in 2024 [3]. MEC offloads computation to edge servers operated by service providers; once compromised, these nodes become targets themselves, triggering service disruption and resource exhaustion [4] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Security threats in MEC networks: IoT devices infected with malware are connected to MEC servers.

Contemporary MEC deployments adopt a two-tier edge architecture: (i) Proximal Edge Servers (PES)—latency-critical gateways near IoT access points—and (ii) Supplementary Edge Servers (SES)—better-provisioned nodes enlisted to extend coverage, absorb overload, or federate resources across administrative domains [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. This layered design balances near-device responsiveness at PES with the strategic flexibility of an SES overlay, which we leverage for decentralized FL.

Network-behavior monitoring is a practical way to detect compromised devices when direct instrumentation is infeasible or privacy-sensitive [11,12]. Federated learning (FL) trains such detectors collaboratively across data-siloed domains without centralizing raw traffic [13,14,15]: clients transmit model updates instead of packet traces, aiding data sovereignty and regulatory compliance. N-BaIoT has become the de facto FL-IMD benchmark because it provides per-device traces that naturally induce non-IID, client-wise partitions and allow cross-device generalization studies [14,15,16,17].

Despite progress, two issues remain insufficiently addressed. First, privacy leakage from shared model updates persists: gradient inversion, membership inference, and related attacks can expose sensitive local traffic characteristics when updates are unprotected or only lightly obfuscated [13,14,15]. Second, aggregation reliability and trust are often assumed rather than engineered. Most frameworks depend on a logically central aggregation server that (i) constitutes a single point of failure, (ii) concentrates trust and attack surface, (iii) risks compute/bandwidth bottlenecks at scale, and (iv) complicates deployment across multi-operator or zero-trust MEC environments [14,15,17]. Our earlier RPFL framework [18] grafted homomorphic encryption (HE) and signatures onto FL but still relied on a central server.

Research question: Can we realize a privacy-preserving, auditable, fully decentralized FL pipeline aligned with MEC’s PES/SES hierarchy that retains high zero-day IoT-malware detection rates while eliminating the central aggregator and avoiding overload on PES nodes?

1.1. Research Gap

Most FL-based IoT-malware detectors still rely on a central aggregator, which is a single point of failure and trust, exposes plaintext updates to inference attacks, and struggles to span multiple MEC operators. Prior work adds cryptography or uses hierarchical FL, but rarely together delivers (a) end-to-end update confidentiality at the aggregation tier, (b) verifiable provenance/audit trails, and (c) removal of the trusted server in a way that fits MEC’s PES/SES resource split. This gap motivates our design. This work. We introduce a two-tier, fully decentralized FL architecture for IoT-malware detection in MEC. PES nodes train locally and encrypt updates with CKKS; SES nodes verify, cache, and homomorphically aggregate ciphertexts. An Algorand-style committee writes a succinct per-round commitment (update digests/URIs and a global-model hash) to an append-only ledger. No entity beyond PES ever holds raw traffic or plaintext updates, and no single SES can dictate the global model.

1.2. Our Contributions

We present a two-tier, fully decentralized FL framework for IoT-malware detection at the MEC edge that does the following:

- Eliminates the central aggregator via a peer-to-peer SES overlay with Algorand-style committees, removing the single point of failure.

- Preserves update confidentiality using CKKS; we expose light vs. heavy parameter profiles to trade precision for payload.

- Enables signed provenance and auditability: PES signs hashed update metadata; committees commit digests/URIs and the global-model hash to a lightweight ledger (ciphertexts stay off-chain).

- Aligns with MEC resources: PES performs training and encryption/decryption; SES handles verification, HE aggregation, and finality.

- Demonstrates generalization and costs: on N-BaIoT under known-device and leave-one-device-out protocols, with per-component runtime and communication overheads (consensus is negligible vs. HE).

- Analyzes security and limits: threat model (honest-but-curious PES; Byzantine SES), integrity guarantees, and practical limits (ciphertext size, TenSEAL serialization), with deployment guidance.

1.3. Organization

Section 2 reviews background and related work. Section 3 summarizes the minimal preliminaries, with formal details deferred to Appendix A. Section 4 presents the framework. Section 5 analyzes security. Section 6 details implementation and experimental setup. Section 7 reports results. Section 8 covers limitations and deployment guidance. Section 9 concludes.

2. Background and Related Work

Federated learning-based IoT malware detection (FL-IMD) sits at the intersection of three lines of work: (i) datasets and partitioning strategies that preserve device heterogeneity, (ii) federated architectures for traffic-based malware detection, and (iii) security mechanisms that protect model updates and the aggregation layer. We review each thread before summarizing the open gaps our framework addresses.

2.1. Datasets and FL-Friendly Partitioning

Most public IoT security corpora were captured in centralized lab settings and require artificial splits to emulate cross-site learning [14]. N-BaIoT is a notable exception: per-device files enable natural client-wise partitions and realistic non-IID distributions across devices, making it the de facto benchmark for FL-IMD and our evaluation choice (see Section 6).

2.2. FL-Based IoT-Malware Detection

Popoola et al. [15] apply FedAvg with a parameter server for zero-day botnet detection, keeping raw traffic local but relying on a trusted central aggregator. Rey et al. [14] train supervised (MLP) and unsupervised (autoencoder) FL models on N-BaIoT with a single server; they also study poisoning robustness, yet model updates remain in plaintext at the server. Regan et al. [19] demonstrate edge-gateway FL with a deep autoencoder coordinated by a server-side aggregator. Wardana et al. [17] propose a hierarchical edge–fog–cloud FL-DNN with a central cloud aggregator and report high accuracy on N-BaIoT.

Takeaway. Across these studies, a central (or hierarchical) server remains the single point of failure/trust, and client updates are exposed in plaintext at the aggregator.

2.3. Security Add-Ons and Their Limits

Unprotected gradients can leak private features via inversion and membership-inference attacks [13,14]. Differential privacy helps but may harm rare-threat detection [20]. Server-side defenses (e.g., cosine-similarity outlier filtering) flag poisoned clients [21] but still presume plaintext updates at a central server and do not remove the single point of failure.

2.4. Our Prior Work: RPFL

RPFL [18] integrates homomorphic encryption and ECDSA with smart-contract checks, improving confidentiality and integrity. However, it retains a central aggregator, so availability/trust bottlenecks and cross-operator deployment frictions remain.

2.5. Positioning and Remaining Gap

In summary, prior FL-IMD systems either (i) assume a central aggregator (trust/availability bottleneck) or (ii) omit end-to-end parameter privacy and audit trails at the aggregation tier. This motivates our design, which combines encrypted updates, signed provenance, and committee-based finality without a trusted server, aligned with MEC’s PES/SES split (details in Section 4).

Table 1 positions our design within the FL-IMD literature and shows that it uniquely combines homomorphic encryption, ledger-backed authenticated provenance, and committee-based aggregation in a design explicitly aligned with MEC’s two-tier PES/SES hierarchy.

Table 1.

Representative FL-IMD studies evaluated on the N-BaIoT dataset, with their main strengths and weaknesses, especially regarding parameter privacy, adversarial robustness, and aggregator trust.

3. Preliminaries

This section includes only the essentials for federated learning (FL), CKKS, ECDSA, and Algorand-style committees needed to follow the design. Algebraic details, protocol-level steps, and full citations are provided in Appendix A (see Appendix A.1, Appendix A.2 and Appendix A.3); the complete per-round pseudocode remains in the main text.

3.1. Federated Learning

We follow the standard FedAvg-style setting with client-wise (PES-wise) non-IID splits; each round, clients train locally and contribute weighted updates to the global model [13]. For general background and system considerations in FL, see [22,23,24].

3.2. Homomorphic Encryption (CKKS)

We encrypt model parameters so SES nodes only see ciphertexts yet can still sum them homomorphically; additions are depth-free, while multiplications consume depth. Precision/noise budget and payload size depend on the polynomial degree and modulus chain [25,26]. Security-level sizing follows the Homomorphic Encryption Standard [27]. Implementation details and the concrete parameter profiles we use are in Appendix A.1 (CKKS via TenSEAL [28]).

3.3. Signatures and Provenance (ECDSA)

Each PES signs a compact per-update metadata record (see Section 4), rather than the CKKS ciphertext itself, to bind provenance while keeping overhead negligible. To prevent nonce-reuse attacks, nonces are generated deterministically per RFC 6979 [29]; see Appendix A.2 for details.

3.4. Committee Finality (Algorand-Style)

A rotating committee of validators reaches finality with a quorum of votes via Algorand’s BA★ fast path under partial synchrony, with VRF-based sortition for non-interactive eligibility [30,31]. Only compact digests/URIs and the global-model hash are recorded on-chain—CKKS ciphertexts remain off-chain (see Section 4); step-by-step protocol details appear in Appendix A.3.

4. Proposed Framework

Scope. We target IoT-malware detection in 5G/6G multi-access edge computing (MEC) deployments, where traffic remains siloed at numerous latency-critical gateways. Our goal is to eliminate the single, trusted FL aggregator while preserving (i) confidentiality of model updates via CKKS homomorphic encryption; (ii) origin authentication and integrity through ECDSA signatures; (iii) round-by-round auditability using a lightweight ledger of per-round commitments; and (iv) seamless deployment on MEC’s two-tier hierarchy—Proximal Edge Servers (PES) and Supplementary Edge Servers (SES)—all without degrading zero-day detection performance.

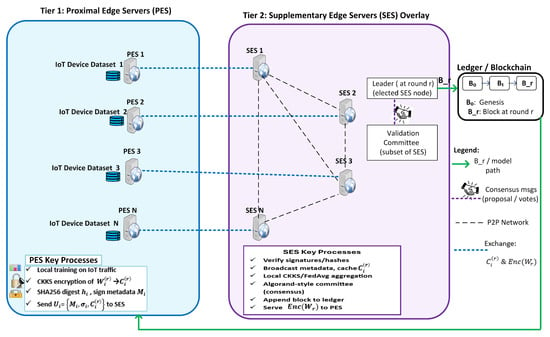

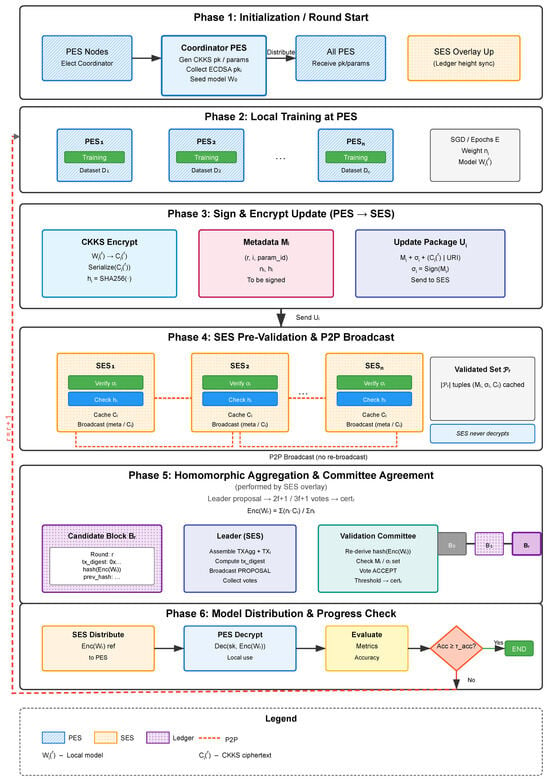

Figure 2 presents the system-level architecture, Figure 3 details the round-level control flow, and Table 2 summarizes all symbols.

Figure 2.

System-level view of the two-tier PES/SES architecture and ledger placement for fully decentralized FL-based IoT-malware detection.

Figure 3.

Per-round control flow of a decentralized FL pipeline for IoT-malware detection: from local training and CKKS encryption at PES to homomorphic aggregation and committee agreement at SES.

Table 2.

Symbols used throughout Section 4.

4.1. Entities and Trust Assumptions

- Proximal Edge Servers (PES): Latency-critical edge nodes near IoT access gateways. Each PES trains a local malware-detection model over proximate traffic, holds (or can reconstruct) decryption key material within its administrative domain, and possesses an ECDSA key pair to authenticate its encrypted updates.

- Supplementary Edge Servers (SES): Better-provisioned edge nodes interconnected in a peer-to-peer (P2P) overlay. SES nodes (a) verify PES update signatures, (b) cache encrypted update ciphertexts, (c) perform homomorphic aggregation to derive the encrypted global model, and (d) execute a lightweight validation-committee agreement round to finalize a per-round block.

- Coordinator PES (bootstrapping role): Generates the CKKS parameter context and system public key, collects PES ECDSA public keys, initializes the genesis ledger state, and distributes the initial (round 0) global model.

Authenticated channels are assumed within each operator domain; PES ECDSA public keys are distributed out-of-band at system setup. SES nodes are only partially trusted; the committee-based agreement layer mitigates Byzantine SES behavior and prevents any single SES from dictating aggregation results, replacing the traditional centralized aggregator. We assume at most f Byzantine SES in any committee; a block is finalized once at least of validator votes (i.e., ) are collected.

4.2. Cryptographic Materials

We instantiate CKKS to support approximate arithmetic over real-valued model parameters. A global CKKS public key (with a parameter identifier) is distributed to all PES; the corresponding decryption material remains within PES administrative domains. Each PES i holds an ECDSA key pair registered at initialization.

Our design combines two complementary mechanisms: CKKS provides confidentiality of model updates across domains, while ECDSA signatures over concise, per-round metadata (which embeds a ciphertext digest) provide authenticity, integrity, and round binding. Concretely, before uploading, each PES attaches

and signs . This lets any SES verify origin and integrity without a central server and allows the ledger to commit only a small record (plus a uri) to the off-ledger ciphertext for auditability.

For how these cryptographic elements integrate with committee selection and finality, see the beginning of Section 4.3.

4.3. Round Protocol Overview

4.3.1. Cryptographic/Consensus Intuition

We use CKKS so SES nodes can homomorphically sum encrypted model parameters without decryption; PES also signs a compact metadata record (SHA-256 digest + ECDSA) to bind provenance and detect tampering. After SES computes the encrypted global model, an Algorand-style committee (size , quorum ) finalizes a block that records only digests/URIs and the global-model hash; ciphertexts themselves remain off-chain. Formal definitions and parameters appear in Appendix A.

Each global training round r proceeds in six phases as shown in Figure 3.

4.3.2. Phase 1: Initialization/Round Start

The Coordinator PES distributes , the CKKS parameter identifier, PES public keys, and the current encrypted global model (for , the seed model). SES nodes synchronize overlay membership and ledger height.

4.3.3. Phase 2: Local Training at PES

Each PES decrypts (if authorized) to recover , trains locally on its dataset, and produces updated weights together with a participation weight (e.g., local sample count).

4.3.4. Phase 3: Sign & Encrypt Update (PES → SES)

- CKKS encryption of

- SHA-256 digest ; sign metadata (ECDSA)

- Send to SES

PES i encrypts under CKKS, yielding , computes , and forms . It signs . The signed package (or (if the ciphertext is stored off-ledger) is sent to an SES, which broadcasts either the full update or (if off-ledger) across the SES P2P overlay. The signature covers only compact metadata (containing the digest), minimizing overhead.

4.3.5. Phase 4: SES Pre-Validation & P2P Broadcast

Upon receiving , an SES verifies with , recomputes , and checks in . Valid local updates are cached, and their tuples are broadcast to all peer SES. Updates received via the overlay are verified and cached but not re-broadcast. After a fixed dissemination window, each SES forms the validated set .

4.3.6. Phase 5: Homomorphic Aggregation & Committee Agreement

After Phase 4, each SES fixes the validated set consisting of updates whose signatures and hashes are verified and that arrived before the dissemination cutoff.

Each SES independently computes

and derives .

Committee selection and voting (Algorand-style):

- VRF sortition. Using the previous block hash as a seed, each SES runs non-interactive VRF-based sortition to determine if it is the leader or a validator in the round-r committee of size and outputs a VRF proof; peers verify the proof and confirm role eligibility locally.

- Aggregation and consistency check. The elected leader packages either or the compact (uriglob, hglob, param_id), plus the ordered update digests and their VRF proof. Validators recompute locally from their cached inputs and verify all metadata/signatures.

- Finality. Upon collecting valid VOTE_ACCEPT messages, the leader (or any validator) assembles a quorum certificate (QC), finalizes block , and appends it to the chain. Only compact fields are written on-chain (digests/URIs and ); ciphertexts remain off-ledger.

4.3.7. Phase 6: Model Distribution & Progress Check

The finalized block’s reference to is served to PES (directly or via ). Each PES retrieves , decrypts to (if authorized), evaluates validation metrics, and either halts (if global accuracy ) or proceeds to round until .

4.4. Data Structures

When large ciphertexts are stored off-ledger, we record only digests and URIs:

Here, and . The field tx_digest is a compact cryptographic digest committing to the ordered transaction set for round r (e.g., a Merkle root). The certificate certr−1 (if included) authenticates the previously finalized block, helping late or recovering SES nodes synchronize without re-running earlier rounds.

Consensus parameters:

- Committee size/quorum: validators; finality with votes under partial synchrony.

- Sortition/eligibility: VRF-based, seeded by the previous block hash; leaders/validators attach a VRF proof, which peers verify.

- Proposal content: ordered update digests and (ciphertexts stay off-ledger).

- Validator check: re-derive locally from cached inputs; accept only matching proposals.

- Ledger record: block header , quorum certificate , , and ; ciphertexts referenced via uri.

4.5. PES and SES Round Procedures

Algorithms 1 and 2 summarize per-round logic.

| Algorithm 1 PES round procedure i (round r). |

|

| Algorithm 2 SES round processing and CKKS-aware committee consensus in round r. |

|

5. Security Analysis

We analyze the scheme’s privacy and security properties. We first state the adversarial model, then argue each guarantee.

5.1. Threat Model

- PES (honest-but-curious): A Proximal Edge Server follows the protocol but attempts to infer information about other domains’ traffic from what it can observe.

- SES (Byzantine): In any round, at most f of the validators may behave arbitrarily—dropping, delaying, equivocating, or forging messages.

- Adversarial goals: (i) extract private traffic features; (ii) alter model updates or ledger history; (iii) halt global-model progress.

Model Poisoning and Mitigations (Design Options)

While SES nodes never see plaintext updates, adversarial PES could attempt model poisoning (e.g., sign-flip or backdoor). Our design accommodates two low-overhead deployment options: (i) committee-side robust aggregation (trimmed mean or coordinate median) to reduce outlier influence, and (ii) a simple magnitude gate on the aggregate (-norm check against a rolling reference) applied prior to dissemination. These options do not require per-client plaintext visibility, are compatible with our pipeline, and add negligible overhead relative to homomorphic aggregation.

5.2. Privacy Guarantees

- Confidential updates at the aggregation tier. Each PES encrypts its local model into using CKKS with parameters sized for at least 128-bit classical security according to the Homomorphic Encryption Standard [27]. CKKS (instantiated over RLWE) provides semantic security against chosen-plaintext attacks (IND-CPA), so SES peers observing only ciphertexts and hashes cannot distinguish encryptions of equal-length plaintexts except with negligible advantage.

- Dataset secrecy vs. global-model exposure. Raw traffic never leaves a PES, and SES nodes observe only CKKS ciphertexts plus signed metadata. After aggregation, the released model reflects a mixture of many local updates and is therefore less directly attributable to any single PES (especially when each round includes a sufficient number of participants).

- Residual inference exposure at the global model. While SES observes only ciphertexts, a decrypted global model (available to PES within their domains) remains subject to the standard FL risk of membership/property inference. Our design supports operational controls that can be enabled by deployment policy: (a) a minimum participant threshold per round to dilute any single contribution; (b) reduced model-release cadence (e.g., every k rounds) to limit across-round differencing; and (c) an optional aggregate-level-DP noise addition before decryption when required. These options are compatible with the encrypted aggregation path and do not change CKKS/consensus logic.

5.3. Integrity and Availability Guarantees

- Authenticity and integrity of submissions. Each metadata tuple is signed as . Validators recompute and check . Thus, any bit-level change to invalidates , and any change to the ciphertext is detected via the hash-consistency check.

- Round consistency. Validators independently recompute ; a block is accepted only when at least of votes coincide (Algorand BA★). Consequently, each round yields a single, globally agreed digest (and associated encrypted model reference).

- Byzantine resilience. With validators, BA★ preserves safety against any f faulty SES and guarantees liveness once partial synchrony holds.

- Auditability and non-repudiation. Every block records plus a quorum certificate, enabling post-hoc attribution of each ciphertext to its signed origin.

5.3.1. Ledger Sustainability

The design records only compact metadata on-chain (block header, quorum certificate, aggregate digest, and per-update digests/URIs), while ciphertexts remain off-chain. The per-round on-chain footprint is the sum of those items for that round, and total storage grows linearly with the number of rounds. Operators can bound long-term growth by retaining only the most recent set of rounds together with periodic checkpoints; this yields effectively linear growth in the chosen retention window while preserving auditability via the certificate chain. Off-chain payloads remain addressable by their uri references.

5.3.2. Sybil Resilience

To reduce the risk of committee capture by many collocated identities, SES registration uses PKI-backed admission; per-round VRF sortition enforces eligibility caps/rate limiting; and, where applicable, a stake-weighted variant further lowers capture probability. These controls complement the / BFT guarantees and do not require per-client plaintext visibility.

5.3.3. Summary

Under standard hardness assumptions for CKKS and ECDSA and the safety-liveness guarantees of Algorand BA★, the framework provides confidentiality of model updates at the aggregation tier, origin authentication and tamper evidence, ledger-backed auditability, and Byzantine-fault-tolerant finalization—without relying on a central trusted server.

6. Performance Evaluation

6.1. Implementation Environment

6.1.1. Hardware and Base System

All experiments were executed on a Google Compute Engine virtual machine (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA; region us-central1) configured with 24 vCPUs and 192 GB RAM, running Ubuntu 24.04 LTS (Canonical Group Limited, London, UK).

6.1.2. Federated Learning Stack (PES Client and SES/Server)

Our experiments rely on Flower [32] (version 1.5.0, Python 3.12.3) and PyTorch [33] (version 2.7.1 + cu126). At start-up, the simulation controller spawns one Supplementary Edge Server (SES) process per client. Each SES communicates with its colocated Proximal Edge Server (PES) via Flower’s gRPC channel and exchanges CKKS-encrypted updates with peer SES nodes over a lightweight Flask/HTTP endpoint.

6.1.3. Homomorphic-Encryption Configuration

We employ CKKS via TenSEAL [28]. To study the accuracy–overhead trade-off, two alternative parameter profiles are evaluated—only one is active in any given run:

- Heavy key .

- Lighter key .

A single public key is broadcast at initialization; the corresponding secret key never leaves PES administrative domains, so SES nodes operate exclusively on ciphertexts. Here N is the polynomial-modulus degree and the CKKS scale factor, following Cheon et al. [25]. The heavy and light profiles expose a controllable security–precision–payload trade-off (Table 5). In our prototype, we encrypt the final fully connected layer; current TenSEAL/Protobuf limits prevent serializing the entire network into a single 8192-slot ciphertext (Section 8.7).

6.1.4. Algorand Consensus Layer (Measurement Harness vs. Production)

Measurement harness. In our 8 SES/8 PES deployment (one PES per SES) with CKKS enabled and P2P SES-to-SES aggregation, we used a private Algorand Sandbox [34] purely as a latency-only commit path. The validator set was fixed at (thus ); the SES nodes act as external clients. At the end of each round, they compute , re-derive , and submit in the note field of a zero-amount self-transaction via the Algorand Python SDK. Per-round consensus finality was consistently RTT-bounded and small, as reported in Section 7.3. This harness isolates the ledger-commit path and is not presented as fault-tolerant nor as a model of churn or adversaries.

Production protocol. In deployment, validator roles rotate among SES via VRF-based sortition seeded by the previous block hash, with a committee of size and finality at votes (see Section 4 for protocol integration and Section 5 for safety/liveness assumptions). Only compact digests/URIs and are recorded on-chain—ciphertexts remain off-ledger. As shown in Section 7.3, the consensus tail is RTT-bounded (a few milliseconds, ∼6.9 ms) and negligible relative to homomorphic aggregation.

6.2. Dataset Configuration for Unsupervised Learning

6.2.1. Dataset Overview

We employ the N-BaIoT dataset as our sole source of IoT traffic and attack traces. N-BaIoT contains packet-flow statistics (115 features) from nine commercial IoT devices, each recorded under benign operation and under Mirai or BASHLITE botnet attacks. Because the traces are grouped by device, the dataset naturally yields a non-IID, device-level partitioning that mirrors a federated setting: in our simulation, K PES nodes each receive the benign traffic of exactly one device for training and threshold calibration, while one device is held out entirely to test cross-client generalization. This arrangement reflects the privacy and trust constraints expected in MEC-based IoT networks and provides a realistic benchmark for unsupervised, federated anomaly detection.

6.2.2. Initial Splitting

For each PES node , the available benign traffic data is chronologically split into three disjoint subsets:

- Test set: 20% of the benign samples, reserved for evaluation on known devices;

- Unused buffer: 1% of the samples, excluded to prevent potential data leakage;

- Train pool: the remaining 79%, used for training and threshold estimation.

6.2.3. Train/Threshold Division and Resampling

The train pool is further divided evenly into

- A training set (39.5%);

- A threshold-selection set (39.5%).

Each PES node’s training set consists solely of benign traffic. To control for sample-size effects, we fix the number of benign training samples per PES to via upsampling or downsampling, performed only after the train/validation/test split to avoid leakage. Normalization is applied per PES using min–max scaling.

6.2.4. Test Dataset Rebalancing

For evaluation, each test set is rebalanced to benign and attack according to benign_prop_resample and p_test_resample. This is applied uniformly across all PES nodes and the unseen device. We use a single rebalanced scenario throughout.

6.2.5. Data Normalization

All input samples are normalized using min–max feature scaling, defined as . This operation is performed element-wise across the 115-dimensional feature vectors. The normalization parameters and are computed independently for each PES node using its local training data only, ensuring no leakage from the threshold-selection or test sets. These values are fixed prior to training and are embedded within each PES node’s model through a normalization wrapper. To maintain numerical stability, the denominator is clamped with a small constant () to prevent division by near-zero values.

6.3. Model Architecture and Training

We adopt an unsupervised anomaly-detection approach based on a shallow autoencoder, following prior results on N–BaIoT [14]. The encoder has one hidden layer with 29 ELU units, and the decoder reconstructs the 115 -dimensional input. The network is trained only on benign samples by minimizing mean-squared reconstruction error (MSE). A normalization wrapper precedes the encoder to apply per-feature min–max scaling; the scaling parameters are computed locally on each PES from its own training data to preserve privacy and reflect client heterogeneity.

Federated schedule. In each round, clients train locally for multiple epochs.

Aggregation. Each SES node performs aggregation using Flower’s FedAvg strategy.

Detection threshold. Each PES computes a local threshold as the 95th percentile of reconstruction errors on its benign validation split. The SES (leader) averages to obtain the global threshold ; the result is validated by a committee, recorded on the ledger, and shared with all PES each round to ensure consistent anomaly classification.

Implementation note. In our prototype, we encrypt only the final fully connected layer due to current TenSEAL/serialization limits (see Section 6.1 and Section 8.7); the framework itself supports full-model encryption.

6.4. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

Because the model was trained solely in an unsupervised anomaly detection setting using only benign traffic, the learned representations are not influenced by the presence or proportion of attack data. As the model’s performance is inherently independent of class balance, we focus our evaluation on the True Positive Rate (TPR) and True Negative Rate (TNR). Accuracy is intentionally omitted, as it can be misleading in imbalanced settings and does not reliably capture the model’s sensitivity to anomalies.

The following metrics are used in our evaluation:

- TP (True Positives): Correctly identified attack samples.

- TN (True Negatives): Correctly identified benign samples.

- FP (False Positives): Benign samples incorrectly classified as attacks.

- FN (False Negatives): Attack samples incorrectly classified as benign.

- True Positive Rate (TPR):

- True Negative Rate (TNR):

Federated Partitioning and Run Schedule

We employ a leave-one-device-out protocol: the nine N-BaIoT devices are split into training clients (one device per PES node), while the remaining device is kept completely unseen for testing. Cycling through all nine possible train/test splits yields nine federations. Each federation is trained for global rounds; within a round, every client runs 120 local epochs on an auto-encoder optimized by Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with learning rate and batch size 64. L2 regularization is tuned over the grid . Hyper-parameters were selected via fine-tuning to balance model performance and training efficiency. The whole procedure is repeated five times, and we report the mean of TPR and TNR across those repetitions.

6.5. Baselines

We compare our framework against three key baselines selected for their relevance to IoT malware detection and federated learning:

- Classical FL-IMD (Centralized, No Privacy): This is our direct ablation baseline, mirroring our framework’s dataset, model, and training strategy but using a standard centralized aggregator without any cryptographic protections (HE or signatures). It serves to isolate and quantify the performance impact of our privacy-preserving, decentralized design.

- Rey et al. [14]: A state-of-the-art centralized FL framework for IoT security. Their “Multi-epoch aggregation” approach uses a central coordinator and simple equal-weight averaging. This baseline represents a high-performing but non-private alternative.

- Asiri et al. [18]: Our prior centralized FL framework that integrates HE and ECDSA to improve privacy and reliability. The original implementation used supervised classification; for a fair comparison here, we adapt RPFL to the same unsupervised autoencoder as our method. This baseline isolates the benefits of moving from a centralized private design to our fully decentralized approach.

7. Results

7.1. Detection Performance on Known Devices

We evaluated our framework through two comparisons: first, quantifying the impact of our security mechanisms on detection performance, then benchmarking against state-of-the-art approaches.

7.1.1. Impact of Security Mechanisms: Baseline Comparison

To isolate the effect of cryptographic protection on detection performance, we compared our framework against classical FL-IMD without security features; the results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Known-device performance: impact of security mechanisms. Heavy-key CKKS preserves TPR; TNR differs by 0.20 percentage points vs. plaintext.

Both approaches, as shown in Table 3, achieved an identical TPR of 0.999, indicating that attack detection capability remains unaffected by our security additions. The TNR decreased marginally from 0.932 to 0.930, which we attribute to computational noise introduced during homomorphic aggregation. This translates to approximately two additional false positives per 1000 benign samples, a reasonable trade-off considering the security benefits gained.

7.1.2. Competitive Analysis: State-of-the-Art Comparison

We then compared our framework with Rey et al.’s established FL-IMD approach to assess competitive performance; the comparison is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison with state-of-the-art FL-IMD.

Rey et al. [14] report a TNR of 0.948, exceeding ours by 1.8 percentage points. Two aspects of their setup differ from ours: (i) they aggregate in plaintext with equal client weights (no sample-size weighting), which in heterogeneous settings can prevent large clients from dominating; and (ii) they avoid homomorphic encryption and ledger commitments, thereby avoiding HE-related numeric constraints and the compute/latency overheads of HE and the ledger. In contrast, their design presumes a trusted centralized server—a premise that may be unrealistic in multi-access edge computing (MEC) deployments.

Asiri et al. [18] matched our framework’s performance and included verifiability features, but its reliance on a centralized server introduces a single point of failure and limits its resilience in decentralized or trustless MEC scenarios.

Our framework exchanges this performance margin for three essential security properties. The homomorphic encryption preserves model privacy even from aggregating servers, while the integrity layer (hash and signing) enables update verification without data exposure. Additionally, the decentralized aggregation eliminates single points of failure, ensuring system resilience against node compromise or failure.

In practice, edge computing environments face various security threats, from compromised nodes to adversarial data injection. While Rey et al.’s approach excels in controlled settings, our framework provides the security guarantees necessary for deployment in these challenging real-world conditions. The 1.8% TNR difference represents an acceptable trade-off for organizations requiring verifiable and privacy-preserving federated learning at the MEC networks.

7.1.3. Model Performance: Lighter-Key vs. Heavy-Key HE (Known-Device)

Comparing lighter-key and heavy-key HE configurations reveals clear differences, as summarized in Table 5. While both preserve attack detection (TPR ), specificity diverges: heavy-key HE achieves TNR , whereas lighter-key HE yields TNR = 0.882 (a 4.8 pp gap, about 48 additional false alarms per 1000 benign samples with lighter keys). This stems from parameter-set-dependent numerical precision in CKKS: the larger polynomial degree and modulus in the heavy-key profile better preserve the fine-grained reconstruction errors that drive autoencoder thresholds, whereas the lighter-key profile introduces more noise, primarily hurting specificity.

Table 5.

Known-device performance under CKKS profiles. Heavy keys preserve TPR and near-plaintext TNR; light keys preserve TPR with ∼3.5 pp lower TNR and ∼71% smaller payload (see Table 7).

7.2. Impact of Security Mechanisms on Unseen Devices

Cross-device generalization (LODO). To assess generalizability without adding new corpora, we adopt a leave-one-device-out protocol across all nine N-BaIoT devices: eight devices participate as clients (PES), while the ninth is held out entirely for testing; we repeat this for all nine folds. Across folds, the heavy CKKS profile preserves TPR at 0.999 and changes TNR by only pp relative to plaintext, whereas the light profile preserves TPR and trades pp TNR for smaller payloads (Table 6). This experiment quantifies how homomorphic encryption (HE) influences detection quality when the model is confronted with a device never observed during training. For every one of the nine IoT devices in N–BaIoT we trained on the remaining eight and evaluated on the held-out device, yielding one run per fold (nine runs in total). All hyperparameters mirror the known-device study; only the security layer changes.

Table 6.

Cross-device (leave-one-device-out) performance under CKKS profiles. TPR remains 0.999; heavy CKKS TNR is percentage points vs. plaintext; light CKKS TNR is percentage points with smaller payload (see Table 6).

As summarized in Table 6, homomorphic encryption leaves attack sensitivity intact (all schemes attain TPR ) while affecting specificity only modestly. Heavy-key HE lowers TNR by a negligible pp (approximately 2 extra false alarms per 1000 benign samples). The lighter-key configuration sacrifices an additional pp of TNR but cuts ciphertext size by roughly , reducing transmission time accordingly (Table 7, Figure 4). Overall, strong-key HE provides privacy and auditability with virtually no loss in operational accuracy.

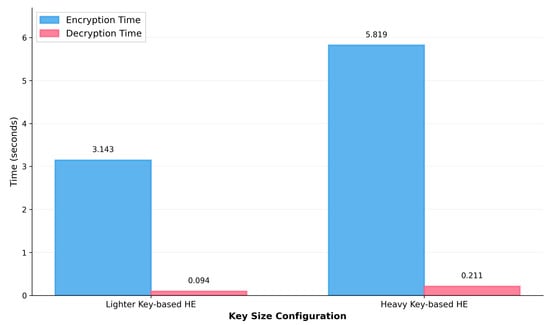

Figure 4.

Encryption and decryption time overhead for different HE key sizes, highlighting the computational asymmetry.

For context, Rey et al. [14] report a TNR of 0.926 on unseen devices with their multi-epoch averaging approach, slightly higher than our plaintext baseline but provided without any privacy guarantees. Their method experiences a 2.2 pp drop from known to unseen devices (0.948 → 0.926), whereas our scheme with heavy-key HE maintains more consistent performance across device types. This suggests that properly parameterized encryption may even help regularize the model against over-fitting to the training devices.

Because benign traffic patterns are highly device-specific, a federation trained on eight devices inevitably treats some legitimate flows from a ninth, unseen device as mild anomalies; hence, a small but expected TNR drop. Attack detection (TPR) remains unaffected because malicious traffic is much more homogeneous across devices.

7.3. Computational and Communication Overhead

Beyond detection accuracy, we evaluated the practical costs introduced by our framework’s cryptographic and consensus mechanisms, focusing on computation at both the client and aggregator tiers, as well as communication payload.

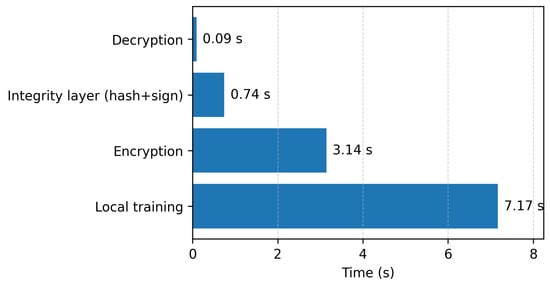

7.3.1. Client-Side (PES) Computational Cost

At the client side, the primary overheads stem from local training and the cryptographic operations required for each update. Figure 5 breaks down the average runtime for a PES node. Local model training is the most time-consuming task, at approximately . This is followed by the CKKS encryption of the model update, which takes with the lighter-key profile. The integrity layer (hashing and ECDSA signing) adds a modest , while decryption of the global model is negligible at . In total, the security mechanisms add about per round, demonstrating that while the overhead is significant, it remains well within practical limits for typical MEC round times.

Figure 5.

Average computational cost at a PES node, broken down by key operations: training, encryption, decryption, and the integrity layer (hash + signature).

Figure 4 further details the pronounced asymmetry in CKKS operations. With the heavy-key profile, encryption takes , while decryption takes only (a gap). This disparity is inherent to CKKS’s design, where encryption involves intensive polynomial arithmetic and noise sampling. Increasing the polynomial degree from (lighter) to (heavy) increases encryption time by , consistent with the complexity of the underlying arithmetic.

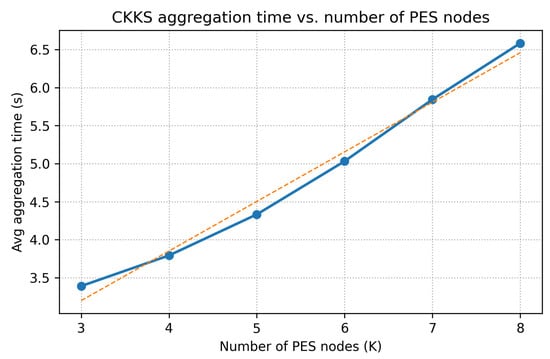

7.3.2. Aggregator-Side (SES) Computational Cost

As shown in Figure 6, SES-side CKKS aggregation time scales linearly with K; a least-squares fit gives (), i.e., each additional client adds about s on our testbed.

Figure 6.

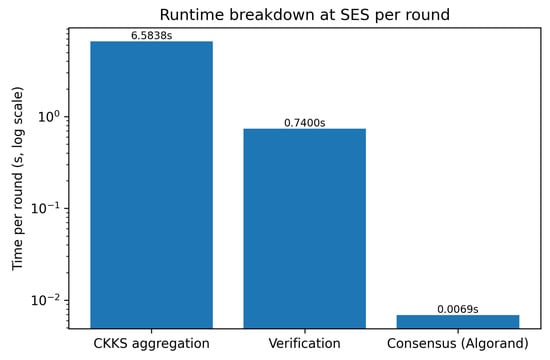

CKKS aggregation time versus the number of participating clients (K). The dashed line shows a linear fit of s ().

Figure 7 decomposes the total round time at an SES node for a round with clients. Homomorphic aggregation is the clear bottleneck, accounting for (89.8%) of the total time. Signature and hash verification takes (10.1%), while the Algorand committee consensus for finality is negligible at just (<0.1%). This confirms that decentralization adds negligible latency; round time is dictated by HE aggregation rather than consensus.

Figure 7.

Runtime breakdown at an SES node per round (, log scale), showing the dominance of homomorphic aggregation.

7.3.3. Consensus Latency Model

We denote by the per-round consensus latency on the fast path, by the wide-area network (WAN) round-trip time between SES peers, by the local verification time (VRF/proof checks and quorum certificate (QC) assembly), and by the SES-side homomorphic-aggregation time. Under these definitions, the BA★ fast path is modeled as

where captures the two network round trips (proposal and vote). Because only compact digests/URIs and votes are exchanged, is bounded by WAN rather than ciphertext size and remains small compared with (Figure 7).

7.3.4. Communication Overhead

Homomorphic encryption introduces a substantial communication cost, a critical factor in MEC environments where backhaul capacity can be a bottleneck [35,36]. As detailed in Table 7, a plaintext model update of only 28 kB inflates to 305.7 MB with the lighter-key HE profile and over 1 GB with the heavy-key profile.

Table 7.

Per-round upload size and inflation factor relative to the 28 kB plaintext model.

Table 7.

Per-round upload size and inflation factor relative to the 28 kB plaintext model.

| Setting | Payload Size | Inflation Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Lighter-key HE | 305.7 MB | 1.1 × 104 |

| Heavy-key HE | 1.06 GB | 3.9 × 104 |

Assuming an illustrative backhaul goodput of 100 Mbit s−1, the upload time for a single client would be approximately 25 s for the lighter key and over 85 s for the heavy-key ciphertext. These magnitudes underscore the importance of careful HE parameter selection and suggest that heavy-key HE may require dedicated network resources, e.g., 5G (and future 6G) network slicing, to remain practical in production.

8. Discussion

We now interpret the results in the context of MEC deployments. We begin with operator-oriented sizing guidance and then examine scalability—committee coordination, the peer-to-peer overlay, and ledger growth. Next, we discuss behavior under adverse network conditions, summarize CKKS/TenSEAL constraints with practical mitigations, and contrast centralized, semi-decentralized, and our committee-based designs. We close with a concise runtime deployment blueprint (Section 8.8).

8.1. Sizing Guidance (Deployment-Oriented)

Select the CKKS profile and the per-round client count K in light of available backhaul and the latency service-level objectives (SLOs) you must meet. Figure 6 and Figure 7 show that aggregation scales roughly linearly with K and dominates the round budget. When bandwidth is ample and specificity is paramount, use the heavy profile; when backhaul is tight and a modest specificity trade-off is acceptable, opt for the lighter profile. Keep K bounded via client sampling or clustering (Section 8.6), use the cluster-aware overlay to localize ciphertext traffic, and tune consensus timeouts to observed RTTs.

8.2. Adversity and Fault-Path Behavior

Real deployments are rarely pristine: links flap, partitions appear, packets are lost, and validators churn. Under such conditions, the protocol preserves safety—no two honest SES finalize conflicting histories—provided at most f of validators are faulty; liveness resumes once partial synchrony returns. The symptom is delay rather than divergence: view changes are triggered, proposals are retried, and finality can slip behind real time. Because consensus exchanges only compact digests and votes, the added latency remains RTT-bounded (see Figure 7); homomorphic aggregation continues to be the pacing term.

8.3. Limitations

Our empirical study focuses on N-BaIoT; to mitigate single-corpus risk, we report leave-one-device-out results across all nine devices. Broadening validation to additional IoT corpora and deployment environments is a natural next step. Our prototype uses a shallow autoencoder due to current CKKS/serialization constraints; the framework accommodates higher-capacity architectures, although they imply larger ciphertexts and higher homomorphic-encryption costs, which merit a dedicated evaluation.

8.4. Architectural Contrast: Centralized, Semi-Decentralized, Committee-Based

We contrast three deployment archetypes, each trading efficiency, resilience, and trust in different ways. Centralized: A single-aggregator design dispenses with committee coordination and executes one CKKS aggregation per round; however, it concentrates trust and introduces a single point of failure—if the server is isolated by a partition, clients behind the cut cannot progress. Semi-decentralized: Regional multi-aggregators attenuate wide-area exposure and latency, yet trust and failure still pool within regions; cross-region fusion reintroduces an upper-tier bottleneck. Committee-based (ours): The SES overlay distributes decision-making across the edge: with validators, safety holds for Byzantine nodes. Because consensus exchanges only compact digests and votes, its latency is RTT-bounded and payload-light; homomorphic aggregation therefore remains the pacing term (Figure 7). In short, centralized maximizes computational efficiency at the cost of resilience, semi-decentralized improves locality without removing single points of trust, and our committee design preserves low latency while eliminating the trusted aggregator.

8.5. Dataset Diversity & Generalizability

N-BaIoT is a widely used FL-IMD benchmark because it provides per-device traces that enable natural client-wise partitioning and realistic non-IID distributions. Nevertheless, it does not cover the full spectrum of IoT protocols, vendor stacks, or long-tailed benign behaviors. To probe cross-device generalization without introducing new corpora, we adopt a leave-one-device-out (LODO) protocol across all nine devices (see Section 7.2/Table 6): the heavy-key CKKS profile retains TPR (0.999) with a pp TNR delta vs. plaintext, while the light-key profile retains TPR and trades pp TNR for smaller payloads. However, larger and more diverse IoT corpora—spanning vendors, protocols, and deployment conditions—are needed to faithfully stress-test FL scalability in MEC settings.

8.6. Optimizing Latency and Scalability in Peer-to-Peer Aggregation

As shown in Figure 6, aggregation scales with K and dominates round time; committee finality remains a short, RTT-bounded tail (Figure 7).

8.6.1. Scaling Properties

Committee coordination. Finality is obtained from a small, fixed committee of validators. Consequently, message exchange and verification cost are with , independent of the installed base N. If the per-round participant set K is kept bounded via client sampling, the consensus contribution remains a short, RTT-bounded tail (Figure 7).

P2P overlay: A bounded-degree SES overlay caps per-node gossip load, and a cluster-aware topology localizes heavy traffic. Partitioning n SES into k clusters reduces potential peer exchanges from to ; across clusters, only compact digests and URIs are exchanged, while bulky ciphertexts stay local.

Ledger growth: On-chain records carry only compact metadata—headers, digests, URIs, and quorum certificates (Section 4.4)—so per-round on-chain state is and total growth is linear in rounds. Retention can be bound with a sliding window plus periodic checkpoints; ciphertexts remain off-ledger under a content-addressed uri with redundancy/pinning.

8.6.2. Cluster-Aware Overlay

To curb both bandwidth and tail latency at larger scales, we envision a hierarchical, cluster-aware deployment. PES nodes are partitioned into geographic or network-affinity clusters of 10–20 nodes, each served by a local SES. If the SES overlay is decomposed into k disjoint clusters of size with dense intra-cluster connectivity, the potential P2P exchanges drop from to

That is, a reduction linear in k. Inter-cluster synchronization can then proceed via a light SES–of–SES layer that exchanges only digests and URIs, keeping bulky ciphertexts local.

8.6.3. Latency Budget and Overlap

The SES round time can be written as

where dissemination and consensus are network-bound and homomorphic aggregation is compute-bound. In practice, overlaps with PES encryption and SES fetching; adds only a short tail. The dominant term is , which in our measurements is approximately s.

8.7. TenSEAL in Practice: Implementation Pitfalls and Mitigations

Our encryption design is governed by three pragmatic constraints:

- Depth. CKKS supports additions and multiplications; each non-linear activation (ReLU, sigmoid, etc.) must be approximated by a polynomial. Such approximations exhaust the noise budget long before a full forward–backward pass can complete at the parameter sets we target.

- Memory. The current TenSEAL/Protobuf stack imposes an internal buffer cap that prevents a ciphertext from reaching the full slot capacity permitted by CKKS. Even the first dense layer can exceed this library limit and raise an array-size exception, despite ample host RAM. This restriction stems from the serializer rather than the CKKS scheme itself.

- Bandwidth. A CKKS ciphertext is two to four orders of magnitude larger than the corresponding plaintext tensor; shipping these payloads across the MEC backhaul quickly dominates local encryption time.

To remain within all three bounds, we currently encrypt only the final fully connected layer. Future work will explore ciphertext compression, the hierarchical SES clustering outlined in Section 8.6, and bootstrapped CKKS variants, which promise to relax both depth and memory pressure [37].

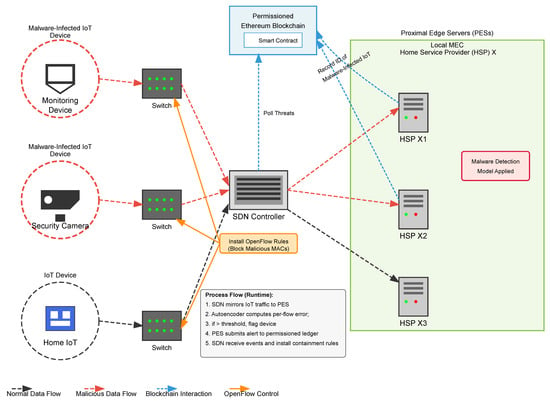

8.8. Edge-Side Deployment of the Trained Detection Model

We describe a post-training deployment pattern for real-time anomaly detection in MEC-enabled IoT networks. Figure 8 illustrates the system-level data flow for this operational phase. At runtime, only Proximal Edge Servers (PES) perform inference; the SES overlay used during training and aggregation is not on the critical path.

Figure 8.

Blockchain-enabled runtime deployment. Trained autoencoders run on PES, while a permissioned Ethereum ledger and SDN applications coordinate enforcement using compact, signed alerts.

The SDN controller mirrors IoT traffic to PES nodes for analysis. Each PES runs the trained autoencoder and computes a per-flow reconstruction error; when this error exceeds a statistically derived threshold (e.g., the 95th percentile of benign reconstruction errors), the source device is flagged as potentially compromised. To minimize privacy exposure, alerts reference devices pseudonymously (e.g., via privacy-preserving tokens) and include a short expiration window, rather than exposing raw identifiers. Alerts are submitted to a permissioned Ethereum ledger via a smart contract, creating an immutable record and emitting events that SDN applications subscribe to. Upon receipt, the SDN controller installs containment rules (e.g., OpenFlow drops or rate limits) without manual intervention. This operational ledger is distinct from the training-time committee ledger in Section 4; it is used solely for enforcement events and stores compact metadata (hash, timestamp, policy tag), never raw packet traces or training artifacts.

The blockchain integration offers three practical benefits. First, decentralization avoids single points of failure and enables parallel alerting across PES nodes, reducing coordination bottlenecks. Second, the append-only log provides auditability through timestamped, tamper-evident records of detections and actions. Third, smart contracts automate alert dissemination to SDN applications, enabling rapid, operator-free enforcement. The same mechanism can support cross-operator threat-intelligence exchange within a shared, permissioned consortium network.

9. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, we addressed the critical need for a secure, private, and resilient framework for collaborative IoT malware detection within decentralized MEC environments. Traditional FL systems fall short by relying on a single, trusted aggregator, which introduces significant security and operational risks. We designed and validated a novel two-tier architecture that overcomes these limitations by uniquely integrating peer-to-peer aggregation, homomorphic encryption for confidentiality, and a ledger-based committee for decentralized, auditable finality. Our empirical evaluation on the N-BaIoT dataset confirms the framework’s practical viability, demonstrating that the system achieves excellent detection performance (>99% TPR) with only a negligible trade-off in specificity in exchange for robust, end-to-end privacy. The results prove that eliminating the central server is feasible without creating a new performance bottleneck, thereby providing an effective blueprint for deploying collaborative security services in next-generation edge networks.

Building on this foundation, future work will focus on enhancing scalability and communication efficiency through hierarchical SES overlays and advanced ciphertext compression. We also plan to explore next-generation cryptographic methods, such as bootstrapped FHE and zero-knowledge proofs, to support more complex models and develop robust defenses against adversarial attacks like model poisoning in the encrypted domain. A key final step—guided by the feasibility evidence and the dataset generalizability discussion—will be to validate the framework in a physical MEC testbed and extend its application beyond malware detection to other distributed edge-intelligence tasks.

Author Contributions

M.A.: Devised the study concept, designed the methodology, coded the software, carried out the simulations and investigations, validated the findings, and prepared the first manuscript draft. M.A.K. and R.M.A.: Offered supervision and undertook critical review and revisions. B.S.A. and F.E.E.: Contributed to the manuscript’s review and editorial refinement. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at king Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is publicly available and can be accessed at the following link: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/detection_of_IoT_botnet_attacks_N_BaIoT (accessed on 5 August 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Cryptographic and Consensus Preliminaries

Appendix A.1. CKKS: Approximate Homomorphic Encryption

We adopt the Cheon–Kim–Kim–Song (CKKS) scheme for approximate arithmetic over real/complex vectors [25,38]. Let

be the cyclotomic ring with N a power of two. A tensor is encoded as a plaintext polynomial at scale . Encryption with public key and randomness u yields

where are discrete-Gaussian. Additions are depth-free; multiplications consume one level of the coefficient-modulus chain and are followed by rescaling. Decryption with recovers , which decodes to at the target precision.

Parameter Profiles Used

We consider two profiles to expose a precision–payload trade-off:

- Heavy key: , modulus chain , .

- Light key: , modulus chain , .

We implement CKKS via TenSEAL [28] integrated into Flower [39] to encrypt layer weights on-the-fly.

Appendix A.2. ECDSA: Authenticity and Integrity

We instantiate the Elliptic-Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) on curve P-256 (secp256r1) as specified by the NIST Digital Signature Standard, FIPS 186-5 [40]. Security strength alignment and key-size guidance follow NIST SP 800-57 Part 1 Rev. 5 [41,42]. Hashing uses SHA-256, standardized by NIST’s FIPS PUB 180-4 [43]; to prevent nonce reuse, ECDSA nonces are generated deterministically per RFC 6979 [29].

Each PES i forms the metadata

and computes the signature . Validators verify using and recompute from the received ciphertext to ensure tamper evidence, origin binding, and replay protection. Only the compact metadata and digest are signed to minimize overhead while still binding each ciphertext to its origin (see also Section 4 for the end-to-end flow).

Appendix A.3. Algorand-Style Committee Consensus

We adapt Algorand’s BA★ fast path with verifiable-random-function (VRF)–based, non-interactive sortition [30] and follow the protocol engineering guidance in the Algorand documentation [31]. In our setting, the committee size is with quorum (Byzantine threshold f) under partial synchrony.

Per-Round Flow

The following applies for each global round r:

- Sortition. A VRF seeded by the previous block hash elects one leader and a validator set of size [30].

- Proposal. The leader proposes together with its VRF proof [30,31].

- Validation. Each validator independently recomputes from its cached inputs and, if consistent, returns a signed VOTE_ACCEPT.

- Finality. Upon collecting valid votes, the proposal is finalized with a quorum certificate and appended as block [30].

Only compact digests/URIs and the global-model hash are recorded on-chain; bulky CKKS ciphertexts remain off-chain to respect MEC latency/bandwidth budgets while retaining auditability (see Section 4).

References

- Coston, I.; Plotnizky, E.; Nojoumian, M. Comprehensive Study of IoT Vulnerabilities and Countermeasures. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batewela, S.; Liyanage, M.; Zeydan, E.; Ylianttila, M.; Ranaweera, P. Security Orchestration in 5G and Beyond Smart Network Technologies. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 554–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SonicWall Inc. 2025 SonicWall Cyber Threat Report: Executive Summary. 2025. Available online: https://www.sonicwall.com/resources/white-papers/executive-summary-2025-sonicwall-cyber-threat-report (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Ma, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, F.; Xie, Q.; Chen, K.; Lv, C.; He, Y.; Li, F. A Survey of DDoS Attack and Defense Technologies in Multiaccess Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 1428–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Sorour, S.; Elsayed, S.A.; Hassanein, H.S. Cost and delay-aware service replication for scalable mobile edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 10937–10950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Jin, R.; Dai, H. Deep PDS-learning for privacy-aware offloading in MEC-enabled IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 4547–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Sorour, S.; Hassanein, H.S. Group-delay aware task offloading with service replication for scalable mobile edge computing. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2020—2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 7–11 December 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Sorour, S.; Hassanein, H.S. Group delay-aware scalable mobile edge computing using service replication. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 11911–11920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cai, Q.; Luo, Y. Multi-edge collaborative offloading and energy threshold-based task migration in mobile edge computing environment. Wirel. Netw. 2021, 27, 4903–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Sorour, S.; Elsayed, S.A.; Hassanein, H.S. Profitable and Scalable MEC: Reputation-Based Service Replication via Stackelberg Game. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Jabraeil Jamali, M.A. Internet of Things intrusion detection systems: A comprehensive review and future directions. Clust. Comput. 2023, 26, 3753–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoufi, M.A.; Siraj, M.M.; Ghaleb, F.A.; Al-Razgan, M.; Al-Asaly, M.S.; Alfakih, T.; Saeed, F. Anomaly-Based Intrusion Detection Model Using Deep Learning for IoT Networks. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 141, 823–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Agüera y Arcas, B. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS 2017), Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; Volume 54, pp. 1273–1282. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v54/mcmahan17a.html (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Rey, V.; Sánchez, P.M.S.; Celdrán, A.H.; Bovet, G. Federated learning for malware detection in IoT devices. Comput. Netw. 2022, 204, 108693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, S.I.; Ande, R.; Adebisi, B.; Gui, G.; Hammoudeh, M.; Jogunola, O. Federated deep learning for zero-day botnet attack detection in IoT-edge devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 3930–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Mathov, Y.; Mirsky, Y.; Shabtai, A.; Breitenbacher, D.; Elovici, Y. N-baiot—Network-based detection of iot botnet attacks using deep autoencoders. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2018, 17, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, A.A.; Sukarno, P.; Salman, M. Collaborative botnet detection in heterogeneous devices of Internet of Things using federated deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 13th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications (ICSCA 2024), Bali Island, Indonesia, 1–3 February 2024; pp. 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, M.; Khemakhem, M.A.; Alhebshi, R.M.; Alsulami, B.S.; Eassa, F.E. Rpfl: A reliable and privacy-preserving framework for federated learning-based iot malware detection. Electronics 2025, 14, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, C.; Nasajpour, M.; Parizi, R.M.; Pouriyeh, S.; Dehghantanha, A.; Choo, K.K.R. Federated IoT attack detection using decentralized edge data. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2022, 8, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.M.S.; Celdrán, A.H.; Xie, N.; Bovet, G.; Pérez, G.M.; Stiller, B. Federatedtrust: A solution for trustworthy federated learning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 152, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thein, T.T.; Shiraishi, Y.; Morii, M. Personalized federated learning-based intrusion detection system: Poisoning attack and defense. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 153, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Qu, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Gao, L. Asynchronous federated learning on heterogeneous devices: A survey. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 50, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wen, Z.; Wu, Z.; Hu, S.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; He, B. A survey on federated learning systems: Vision, hype and reality for data privacy and protection. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 3347–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.H.; Kim, A.; Kim, M.; Song, Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2017; Takagi, T., Peyrin, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10624, pp. 409–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.V.T.; Messai, M.L.; Gavin, G.; Darmont, J. A survey on implementations of homomorphic encryption schemes. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 15098–15139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Chase, M.; Chen, H.; Ding, J.; Goldwasser, S.; Gorbunov, S.; Halevi, S.; Hoffstein, J.; Laine, K.; Lauter, K.; et al. Homomorphic encryption standard. In Protecting Privacy Through Homomorphic Encryption; Lauter, K., Dai, W., Laine, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaissa, A.; Retiat, B.; Cebere, B.; Belfedhal, A.E. TenSEAL: A library for encrypted tensor operations using homomorphic encryption. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.03152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornin, T. Deterministic Usage of the Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA) and Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA). Request for Comments 6979, Internet Engineering Task Force. August 2013. Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc6979 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Gilad, Y.; Hemo, R.; Micali, S.; Vlachos, G.; Zeldovich, N. Algorand: Scaling Byzantine agreements for cryptocurrencies. In Proceedings of the 26th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP 2017), Shanghai, China, 28–31 October 2017; pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gorbunov, S.; Micali, S.; Vlachos, G. Algorand Agreement: Super Fast and Partition Resilient Byzantine Agreement. In Cryptol. ePrint Arch; 2018; Report 2018/377; Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/377 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Beutel, D.J.; Topal, T.; Mathur, A.; Qiu, X.; Fernandez-Marques, J.; Gao, Y.; Sani, L.; Li, K.H.; Parcollet, T.; de Gusmão, P.P.B.; et al. Flower: A friendly federated learning research framework. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.14390. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Algorand Sandbox, Version 3.2.0; 2025. Available online: https://github.com/algorand/sandbox (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Pham, Q.V.; Fang, F.; Ha, V.N.; Piran, M.J.; Le, M.; Le, L.B.; Hwang, W.J.; Ding, Z. A survey of multi-access edge computing in 5G and beyond: Fundamentals, technology integration, and state-of-the-art. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 116974–117017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, T.; Samdanis, K.; Mada, B.; Flinck, H.; Dutta, S.; Sabella, D. On multi-access edge computing: A survey of the emerging 5G network edge cloud architecture and orchestration. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 1657–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossuat, J.P.; Mouchet, C.; Troncoso-Pastoriza, J.; Hubaux, J.P. Efficient bootstrapping for approximate homomorphic encryption with non-sparse keys. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2021; Canteaut, A., Standaert, F.-X., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12696, pp. 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuglova, E.; Kucherov, N. An overview of modern fully homomorphic encryption schemes. In Current Problems in Applied Mathematics and Computer Science and Systems; Alikhanov, A., Lyakhov, P., Samoylenko, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 702, pp. 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adap. Flower: A Friendly Federated Learning Research Framework. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/adap/flower (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- FIPS 186-5; Digital Signature Standard (DSS). Federal Information Processing Standards Publication 186-5. National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Barker, E. Recommendation for Key Management: Part 1–General; NIST Special Publication 800-57 Part 1, Rev. 5; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Zheng, J.; Din, N.; Hussain, M.T.; Ullah, F.; Yousaf, M. Elliptic Curve Cryptography; Applications, challenges, recent advances, and future trends: A comprehensive survey. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 47, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIPS 180-4; Secure Hash Standard (SHS). Federal Information Processing Standards Publication 180-4. National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).