Abstract

Cloud computing as a technology has the capacity to enhance cooperation, scalability, accessibility, and offers discount prospects using improved and effective computing, and this capability helps organizations to stay focused. Ontologies are used to model knowledge. Once knowledge is modeled, knowledge management systems can be used to search, match, visualize knowledge, and also infer new knowledge. Ontologies use semantic analysis to define information within an environment with interconnecting relationships between heterogeneous sets. This paper aims to provide a comprehensive review of the existing literature on ontology in cloud computing and defines the state of the art. We applied the systematic literature review (SLR) approach and identified 400 articles; 58 of the articles were selected after further selection based on set selection criteria, and 35 articles were considered relevant to the study. The study shows that four predominant areas of cloud computing—cloud security, cloud interoperability, cloud resources and service description, and cloud services discovery and selection—have attracted the attention of researchers as dominant areas where cloud ontologies have made great impact. The proposed methods in the literature applied 30 ontologies in the cloud domain, and five of the methods are still practiced in the legacy computing environment. From the analysis, it was found that several challenges exist, including those related to the application of ontologies to enhance business operations in the cloud and multi-cloud. Based on this review, the study summarizes some unresolved challenges and possible future directions for cloud ontology researchers.

1. Introduction

The cloud has generated enormous interest within academia and other decision-making bodies, shaping their perception of the cloud computing environment. Based on the definition from the National Institutes of Standards and Technology (NIST), "Cloud computing is a model for enabling ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications, services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction" [1]. The word ‘cloud’ has been used on various occasions, such as in describing large telecommunications networks even in the 1990s [2]. However, during his paper presentation at the Search Engine Conference in 2006, Eric Schmidt used the world cloud computing for the first time as an approach to Software-as-a-Service (SaaS). It was used to analyze the business model of providing services over the Internet [3,4,5]. Cloud computing is regarded as a technique in which IT services are offered using low-cost computing units connected by Internet Protocol (IP) networks [6].

Cloud computing provides a distinct opportunity for enterprises to quickly become competitive and utilize the advantage of information technology (IT) services-based solutions with a reduced (upfront) cost. This also provides the necessary platform for companies to globalize their processes while improving and/or streamlining business operations [7]. Cloud computing is increasingly embedded in the support of critical business functions of enterprises [8]. Cloud computing has the ability to create enormous opportunities for various business strategies and help companies stay focused and become more competitive [9]. The drawback here is that the dispersed nature of the cloud lends itself to different problems with security and privacy threats at the top of the list [10], coupled with regulations and other factors that influence the external business environment in which the organization operates [8]. The baseline for the definition of cloud computing must include scalability and virtualization [11]. Cloud technology has sets of attributes that distinguish it from other technologies; however, services in this category are affected by heterogeneity challenges. As such, cloud services have many challenges to resolve, such as conflicts arising from limited knowledge about cloud resources and service description, security, interoperability, service discovery, and selection [12].

Ontologies are used to model knowledge management systems where such functions as searching, matching, and visualization can be implemented. It improves the interpretation of cloud components and integration of similar definition services, and deciphers dissimilar representations of the equivalent entity [13]. Ontology is employed in cloud services due to its ability to provide a common-access information layer. This capacity can offer an environment that allows it to display the amount of service it has in the cloud more cohesively and hide its differences. Thus, it has a profound effect as it improves solutions even for many of the problems associated with relocation and service configuration [11,12].

In the present work, our aim is to discuss state-of-the-art ontologies in cloud and multi-cloud computing. Specifically, the contributions of the present work are summarized below:

- i.

- An extensive review has been carried out to investigate cloud ontology techniques for viable cloud computing.

- ii.

- Legacy ontology computing techniques have been matched with the ontology of cloud computing based on shared properties.

- iii.

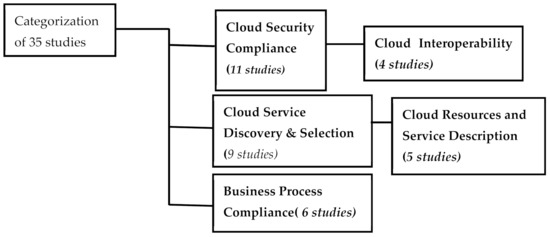

- The current study on cloud computing ontologies is organized into four categories: Cloud security, Cloud resources and services description, Cloud interoperability, and Cloud services discovery and selection.

From the systematic review of selected articles, some of the closest articles to this study are the works carried out by Androcec and Seva [11], and Opara-Martins et al. [9], although they did not consider Business Process Compliance (BPC) with cloud computing standards. This study intends to improve on these works by considering compliance of business processes; it also considers alternatives to the cloud technology like the fog and edge technologies in a bid to create awareness of emerging technologies within the cloud environment.

The following section presents a brief discussion of the models according to the NIST standard descriptions.

2. Background and Related Work

Information Technology (IT), when used as a Service (ITaaS), comprises applications and servers, databases, and a data server bus that provides and supports applications that can be rented from private vendors or designed by a person [14]. Within ITaaS, there exist three layers, beginning with Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS) [14], and Software as a Service (SaaS) [15]. These are usually referred to as service models and deployment models [1].

2.1. Deployment Models

The deployment model (irrespective of the service model) is divided into five categories of clouds, namely: Private, Public, and Hybrid Cloud, with the shared concept called community cloud and the multi-cloud [1,16].

Private cloud is one where computing access is confined within the organization. Its operations are based on a pool of shared resources. It should be noted that this cloud model is entirely operated and managed in-house by the organization’s IT specialist(s), and access to resources is over a secured intranet.

Advantages of the private cloud:

- i.

- Enhanced control: the proprietor controls access in and out of the network, sets the security policies and regulates user behavior.

- ii.

- Security and Privacy: improved access and security is possible when resources are segmented within the same infrastructure.

- iii.

- Tailored: solutions are modified to meet the company’s specific need.

Disadvantage of the private cloud:

- i.

- Controlled scalability: this cloud model has limitations on scalability because it is a function of underlying hardware. It is scaled within the resource capability of the owners.

- ii.

- Hugh budget: the overhead is higher compared to public cloud since the owner would be expected to pay for every resource at his disposal.

Public cloud is one where cloud services are provided as open access for the public [2,16].

Since the public cloud is opened to just anybody, the security cannot be guaranteed; in the public cloud, infrastructural services are offered over the internet. This arrangement gives ownership to the vendor and not the client.

Advantages of the public cloud:

- i.

- Marginal Investment: it is a good option for users in need of instant cloud service, it has little or no advance payment as it is a pay-as-you-go service model.

- ii.

- Initial capital outlay: the client is not bordered about the hardware infrastructural setup as this is borne by the vendor.

- iii.

- Management is not an option: the client does not concern itself with managing the public cloud infrastructure.

- iv.

- Scalability: the system has the capacity to respond to clients’ resource needs at any time.

Disadvantages of the public cloud:

- i.

- Security and Privacy: due to public access, its protective capacities against criminals are weak.

- ii.

- Reliability: The system is vulnerable to failures mainly due to increased traffic from several clients.

Hybrid cloud is the merging of private and public clouds, in which offerings from each domain are absorbed in a combined manner, having some relationships with some external service providers [17].

Advantages of the hybrid cloud:

- i.

- Robust and control: with flexibility, it is possible to create a solution to meet your business need on-demand.

- ii.

- Budget: there is a reduction in cost due to the merger between private and public clouds; this is because public cloud offers free scalability. Therefore, depending on the task at hand, there may or may not be any cost attached.

- iii.

- Security: data integrity is guaranteed to a very large extent due to proper data segregation.

Disadvantage of the hybrid cloud:

- i.

- Maintenance: they may need for extra cost on maintenance when using the hybrid cloud model.

- ii.

- Difficult Integration: the process of integration may become complex when attempting to integrate two dissimilar models.

Community cloud is a cloud facility reserved for a specific community’s usage based on organizations with a shared interest. It could be managed individually or by more members of the organization, and it can be situated on-site or off-site.

Advantages of the community cloud:

- i.

- Effective budget: overhead is light since numerous groups take responsibility for sharing the cloud.

- ii.

- Shared resources: it provides the platform to share cloud resources and infrastructure, which in turn reduces cost of running and maintenance.

Disadvantages of the community cloud:

- i.

- Restriction on bandwidth: there is a fixed bandwidth and data storage within the organization or individual within the community.

Multi-cloud refers to the use of multiple public clouds. A multi-cloud deployment is one in which a company uses multiple public clouds from different cloud providers. In a multi-cloud configuration, a company uses several vendors for cloud hosting, storage, and the full application stack, rather than just one.

Advantages of the multi-cloud:

- i.

- Reduced dormancy: it offers vendors the opportunity to choose regions and zones closest to their clients by reducing or eliminating inactive time.

- ii.

- Service availability: the chance of lack of service is very minimal in multi-cloud configuration.

Disadvantages of the multi-cloud:

- i.

- Inability to manage the system effectively could lead to an increase in cost, which will in turn affect system flexibility.

2.2. Related Surveys of Ontology Usage in Conventional Computing

Ontology is defined as the explicit formal specification of conceptualization [18]. Ontologies are absolutely the pillar of several cloud applications requiring specific domain knowledge [19]. In a cloud environment, identifying and categorizing cloud services in the real world could be challenging because cloud services are provided at various service levels with process data, business logic, and hardware capabilities [20]. Ontology offers organized rules of ideas, each with clearly stipulated guidelines that the machine can understand, thus contributing to machine intelligence [21]. The cloud ontology provides meta-information about data semantics, covering cloud models and their relationships [22]. An ontology represents domain knowledge; the ontology engineer creates ontology classes by making graphical models. This is because models are said to have clear semantics. Based on the above, ontology-based domain knowledge can create unambiguous formal rules such that models can be expressive and interpreted by both machines and humans [23]. Ontology has been applied to many areas since the advent of cloud computing, acting as the missing link between humans and machines to reconcile the heterogeneous nature of the cloud resulting from the lack of standard and governance structure.

Ontologies are indispensable tools for semantic web-based application(s) [24]; hence, their evaluations are paramount for enhancing their (semantic) quality. Most ontology engineers would rather have a modular ontology rather than a general ontology. This is because a good quality modular ontology will promote reusability [25]. The research work carried out by [26] developed an architecture that uses dual core ontology components, namely, the Catalogue and Business Process Ontology, with the capacity for extension through the addition of specific domain ontologies. The catalog ontology explores Universal Business Languages (UBL), whereas the Business Process Ontology uses various applicable business metrics. The business process incorporates rules that different semantic analyzers for commercial practices can understand. The performance of an ontology is said to be efficient based on the depth selected; if the depth is very high, then it implies that the knowledge transfer will be very detailed. Otherwise, knowledge transfer and test will be superficial. Then, there will be no strategic advantage and the system will be lost [27]. The authors of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) framework developed an architecture based on the results of the DAPRECO project. A product of GDPR contains not only legal instructions and ideas obtained within the legal environment, but semantic provisions based on obligations, permissions, and prohibitions [28]. The MEASUR’s ontology was developed as a model that offers a non-dynamic version of the enterprise configurations. This framework is being applied to various scenarios, and it has responded well by providing proof of strength. The authors proposed a system that supported an ontological judgment system to assist stakeholders in accepting such resolutions under electronic governance policies [29]. The authors of [30] proposed a process ontology-based approach to eliminate semantic ambiguity by providing a means to capture rich semantic information residing in business processes, which can be achieved by using domain-specific ontologies. The authors of [31] presented a framework consisting of a list of norms and a generic compliance checking approach based on process execution. The authors of [32] proposed a semantic framework based on an Internet of Things in Business Processes Ontology (IoT-BPO) semantic model. The authors of [33] created an ontology with the ability to depict relationships among various stakeholders involved in the cloud environment. The approach performs security assessment from different customers’ points of view. The authors of [34] presented a security architecture that acts as a base for describing the challenges related to security requirements. In another work, the authors [35] modeled their ITAOFIR (IT Assets Ontology for Information Risk) ontology as a dynamic representation of IT Assets tangibility and risk. Meanwhile, the authors of [36] built a clear representation amid perceptions of protocols and prototypes, and they used semantic business vocabularies coupled with rules based on similarity measures. Explicit modeling and mapping of vocabularies in the compliance framework environment will ease the stress domain experts encounter when screening for the adequacy of specific regulations [37].

The work in [38] proposed a semantic-based service description and discovery framework, which uses a multi-agent approach and ontology with a prototype for cloud service description and discovery in the cloud computing domain. A framework [39] was conceptual in nature and was used for Continued Process Auditing (CPA) relying on domain ontologies.

The authors of [40] developed a reasoning framework that improves the resolution of similarity conflicts between cloud services through a cloud computing ontology.

According to [41], the reason for involving ontologies in cloud computing is due to its ability to reduce search time, rapid discovery of resources, and accurate results. In [42], the authors proposed an approach that could standardize security information and use this description with reasoners, to achieve new understanding and incorporate artifacts into a decision support architecture for some challenges and compliance management to offer total and technically sound decision alternatives to policy makers to achieve this. The authors had to create a complete package of IT with security ontologies that has regulated governance structures based on the ISO 27002 standard. Their framework was validated with a model, methodologies, and artifacts using specialists and clients from small organizations.

An ontology-based infrastructure service discovery and selection model is proposed that specifies practical and non-practical requirements [43]. The authors applied ontology to improve the effectiveness and accuracy of the model to aid consumers in searching and selecting the appropriate vendor with a high level of accuracy. The authors of [44] presented a model to enhance the population of a compliance ontology by using information extracted from an existing Governance Risk Compliance (GRC) architecture to enhance semantic interoperability and reduce the complexity and the disabled functions carried out during compliance monitoring in organizations.

In [45], the authors proposed a framework that generates three fuzzy service ontology configurations such as IaaS, SaaS, and PaaS ontologies. It is intended to define and update cloud service concepts based on fuzzy alignment.

In [46], the authors proposed a framework that incorporates ontology mapping, the development lifecycle of secure systems, natural language processing, including heuristics for applying security policies to compliance issues such as regulations and ethics to focus on compliance to support constant compliance monitoring.

In [47], the authors presented a Compliance Management Ontology (CoMOn) to consider a clear requirement in the compliance management profession and research communities based on shared knowledge of the different ideas that define compliance management practice.

3. Methodology

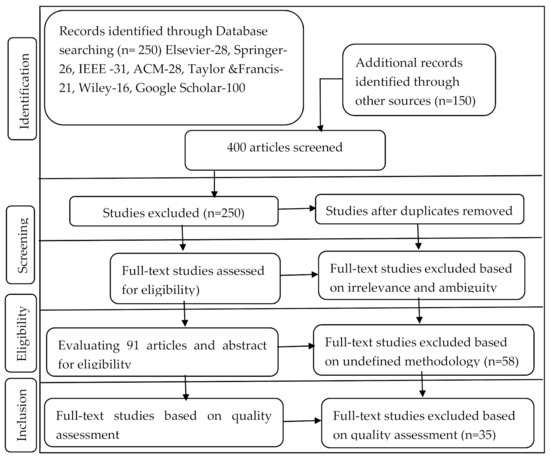

The review process follows the guidelines for performing systematic reviews of the literature, as proposed by [48] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the review process with the selection of studies at various stages.

The approach adopted during the search process includes identifying databases, choosing keywords, and then defining the search strings by specifying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study identified 400 articles, and 58 of these were selected, and after further screening, we settled for 35 articles that meet the objective of the study.

3.1. Methods and Materials

The steps of the whole article include:

- Survey with 400 articles related to cloud computing, ontology, and business process compliance, and eventually settling for 35 articles that meet the study objective.

- Present commendations and best practice procedures based on the knowledge acquired from far-reaching evaluation and assessment of existing literatures.

3.2. Research Questions and Formalization

Following the problems faced by software developers conceptualizing in an explicit format rules that are interpretable by both humans and machines, the study intends to address the challenges based on the motivation and objectives of the study. The questions focus on identifying experts’ ideas and experiences in software engineering with particular reference to ontology in cloud computing areas and approaches from traditional to the cloud so as to determine the future direction(s) in the cloud computing domain.

Motivation is based on the following:

- (a)

- Current cloud ontologies are not specific [12].

- (b)

- The vendor lock-in challenges resulting from customers’ lack of awareness of proprietary standards that do not support interoperability and portability when entering a cloud service contract [9].

- (c)

- The quest for supremacy among major players enhances their unwillingness to settle for a universal standard and thus upholding their incompatible cloud standards and design configuration [49].

- (d)

- Cloud computing is borderless in approach and application; this also means that data within the cloud would be governed by different and sometimes conflicting legislation, thereby creating more security and compliance issues.

The main objective of the study is to achieve an all-inclusive assessment of cloud ontologies, their motivations, and applications. To achieve this, the research focused on the commonly applied quality metrics to specify, analyze, and validate ontology approaches to business compliance in the cloud [50].

The study intends to address the following research questions.

RQ1 :

How has the ontology in cloud computing evolved?

RQ2 :

Which areas have dominated the use of ontologies in cloud computing?

RQ3 :

Which areas have been the least deployed in cloud computing?

RQ4 :

What are problems and future directions in ontology and cloud research?

3.3. Source Selection

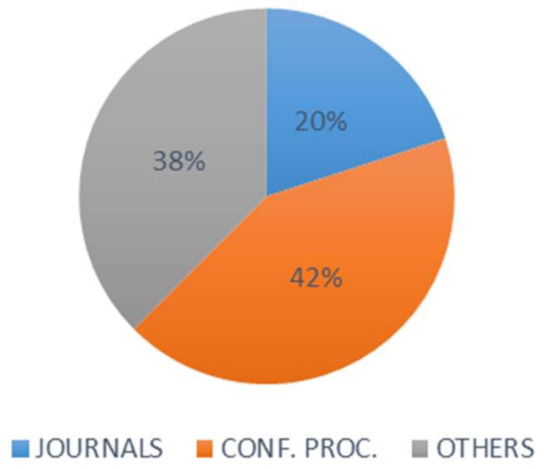

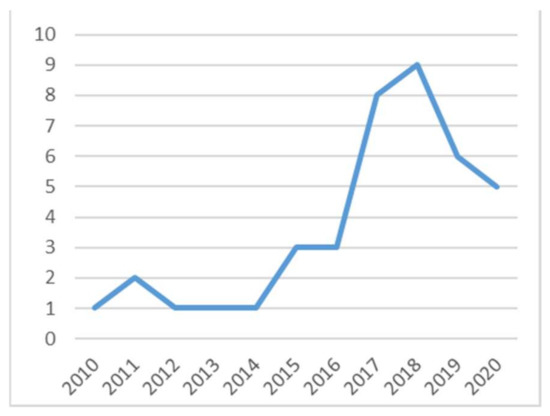

The databases selected for the study include ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, SpringerLink, ScienceDirect – Elsevier, and Google Scholar. At an advanced search, some parameters like "title," “abstract,” and "entire document" were considered, and if not enough, a combination was carried out (if present in the database). With respect to the selection criteria, we applied: (i) Inclusion criteria: work related to research questions, and only papers in English published from 2010 to 2020 were selected from different reputable journals and conference proceedings. (ii) At the level of the exclusion criteria: we removed those articles that had no relationship with the research questions and those not published in English (Table 1 and Table 2). The results of the process are summarized in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The stated headings are provided in the next section to summarize the identified studies and distribution across studies.

Table 1.

Keywords and the search string.

Table 2.

Distribution per publication source types.

Figure 2.

Sources of relevant articles within the study period.

Figure 3.

Number of publications per year.

3.4. Selection Execution

The purpose of the search is to obtain an initial list of studies that would be used for further evaluation. The articles were further evaluated to ensure that they are fit and can be used to provide answers to the research questions defined, which have a duration of 10 years between 2010 and 2020 (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). Table 3 gives an overview of some of the selected studies based on their different categories (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Categorization of primary studies based on present application of ontology in cloud computing.

Table 3.

Summary of some selected studies for review, based on application area of ontology in cloud computing.

4. Information Extraction

Security is regarded as an integral aspect of cloud computing consolidation as a flexible and feasible multipurpose solution. This is based on the perspectives of distinct groups, including researchers from academia, business policy decision makers, and government organizations. The similarities in these various viewpoints provide a clear indication of the crucial nature of security and legal impediments for cloud computing, including data confidentiality, reputation fate sharing, service availability, and provider lock-in. In the immediate subsection, the study lists the selected articles according to their categories.

4.1. Cloud Services Discovery and Selection

In [51], the authors developed a cloud security comparator system that assists consumers who are interested in moving their business to the cloud but are skeptical due to some security issues due to lack of knowledge about different compliance architectures. In [54], the authors developed a prototype methodology to resolve problems of service matching, composition, and selection using Semantic Web technology and QoS parameters based on availability, throughput, cost, and response time, included in the SLA. In [52], the authors presented an application that offers a common platform for discovering and deploying applications for various cloud service providers. The technology known as cloud launch allows applications to be included in a catalog in no definite order while maintaining cloud flexibility allowing developers to offer their applications on multiple cloud environments with little effort. In [53], they proposed the multi-agent methodology to solve the problems arising from users’ inability to discover and select the service that best suits their purpose using the ontological approach. In [55], they proposed SEMREG- Pro, a model for registering semantic services that offers a client interface for service consumers to discover semantic web service data from the registry using a domain ontology. As an added value, it offers consumers the privilege of subscribing to the register and being informed whenever a match to their request was discovered. In [57], the authors proposed the cloud patterns, intending to offer nonspecific and specific elucidations to frequent challenges while defining architectures for cloud applications. They did that by developing platform-dependent patterns that can be assigned to specific platforms provided by specific operators. In [20], they developed a cloud service search engine model to identify and classify cloud services. A detailed ontology was developed to enhance discovery classification and service discovery. In [11], the authors wanted to achieve an all-inclusive view of the ontology for cloud computing together with their areas of application and emphasis. In [56], their position was that the preconditions and postconditions of the services could be communicated in SPARQL. The authors posited that the objective of applying agents is that it can also be expressed in SPARQL. Based on this assertion, it makes sense first to identify the services offered. Then, one can find a suitable service that satisfies the agent and the property specified as a value for precondition and postcondition of the service.

4.2. Cloud Service Description and Selection

In [60], their study designed a case-based energy-saving cloud reasoning agent designed to enhance web services ontology and big data analytics. They reviewed important architectures for developing web services and how to incorporate and aid cloud interaction at the back-end.

In [58], based on the authors’ assertion, cloud services are aiding the continuous expansion of transactions in the cloud environment; it allows cloud consumers the flexibility to acquire and position their needed services through the Internet. The bottleneck in describing major functions of a cloud service would require every service provider to use its version of the service description language. This involves using its own rules and semantics by incorporating models and standards to reach its goal. This, in turn, hinders the cloud computing community from adopting and enforcing common standards, and this limits automatic adoption and deployment of cloud services leading to vendor lock-in.

In [59], Talhi et al. proposed the OntoClean methodology, an approach that was intended to improve collaboration between stakeholders throughout the product lifecycle. It offered solutions that helped users request services ranging from product design and distribution within the cloud environment.

In [61], the authors proposed an information framework, whose emphasis was on the customized creation of a strategy in the cloud manufacturing domain. They applied the semantic web initiative.

In [62], the authors proposed a requirement ontology based on the Unified Problem-solving Method Development Language (UPML) methodology. Its key function was to examine the brokerage requirements, which had the ability to close the gap between high and low requirements specifications. There are three basic concepts: the task, which defines the task that needs to be completed, the problem-solving method, which defines the solutions, and then the problem domain, which defines the concepts for a particular requirements environment. This approach is based on the UPML across the distinct levels in the cloud computing environment.

4.3. Cloud Interoperability

In [50], the authors proposed the PaaSport semantic model, which uses the extension of the OWL ontology based on the Dolce+Dns Ultralite (DUL) ontology. The basic function of the ontological model is to semantically represent the capacities of the Platform as a Service (PaaS) technique for the requirements of applications for deployment. Moreover, it was developed to ensure semantic matching and ranking algorithms that provide the best matching contributions.

In [75], the authors proposed a methodology called cloud lightning ontology, which helps to support different high-performance resources in the cloud. The function is solely to mitigate interoperability challenges between service managers and to service abstractions and sustain the cohesive existence based on existing interoperability standards. The technique supports cloud designers in producing the next generations of cloud computing systems.

In [49], the authors identified and addressed the service-level interoperability challenges that arise when Application Programme Interfaces (APIs) from various active players on the platform as a service are transacted. The use case technique was used to introduce the information of the current user from one platform as a service offering to the application held on a different offer.

In [74], the authors presented a framework for making information exchange operations among heterogeneous sources much easier. The model explores semantic web technologies to allow semantic transmission of data and the perception of the agent’s real-world vision based on the communication process. The system can enhance the extraction of relevant information and encoding its content so that the original semantics are preserved.

4.4. Ontology-Based Approach in Cloud Security and Compliance

Cloud computing ontologies can be applied to different service types; however, their fundamental responsibility is to select and discover the appropriate provision based on the expectations of the available clients and the exposure of cloud service resources available. Ontologies are used as vocabulary or dictionaries of the security domain. They offer reasoning capabilities and help to understand the relationship between entities [82]. Whereas it is a difficult task to systematically detect and correct unknown security challenges, cloud consumers are confused about what security measures to expect from their service providers and whether these measures would meet the security needs of their organizations.

In [61], the authors proposed the declarative methodology SecFog, which can be applied to quantitatively explore the security layers of multi-service application deployment to cloud edge infrastructures. They applied the Problog prototype in their implementation.

In [62], the authors presented a framework of an inference methodology; they collected and analyzed the vulnerabilities of most solutions. Based on this analysis, a premium was placed on the security environment ontology modeling. The authors used a canny measure, a useful tool in a power environment.

In [65], the authors presented an intrusion detection mechanism used in computer network security. Its components include enterprise network-based intrusion detection systems.

In [70], the authors’ attempt was to minimize the search space for the challenges that would be encountered with respect to its execution time. They posited that security defects with known corrections are still being introduced in new systems just waiting to be enabled.

In [71], the authors proposed the framework of an OWL-based security ontology with the aid of protégé that incorporates the OWL/XML language and also includes requirements for the security architecture in line with cloud vulnerability, risk, and threat with the relationship within their different units.

In [73], the authors presented a multilayer cloud architecture model, which provides an improved level of interactions between heterogeneous home devices and cloud service providers. The ontology negotiates the methodology for designing new home-based services to create a more valuable and robust innovative home platform.

In [64], the authors presented a literature review that describes the main attributes, results, problems, and application domains. They observed some discrepancies related to the security assessment literature, which can be part of a future study in this area.

In [68], the authors presented a security ontology framework with a specific focus on cloud-specific virtualization challenges. The ontology model incorporates concepts from existing security and cloud ontologies, where it includes concepts based on security and regulatory standards. They argued that when the ontology is used as a reference model, it activates dynamic changes based on the existing scenario, thus improving the optimal actuality of the security diagnosis.

In [69], the authors developed an ontology rich in semantics whose approach was to model a framework for security threats that incorporates cloud security policies to display the provider data they contain. The new system is equipped with features that allow everyone to use the system without difficulties, including a security policy recommender and an application for new clients planning to move their business to the cloud.

In [72], Singh & Pandey (2014) proposed an analysis based on the relative capacity or otherwise of current ontological security approaches in the cloud. They also pointed out the directions research will follow going forward. This is based on the shortcomings identified from the articles they analyzed in their study.

In [63], the authors proposed an ontology-based access control model called Onto-ACM, which offers a flexible admission mechanism using context reasoning like context permission level with a policy for each administrator and user; this model is thought to be rich in semantic analysis. The system is convenient and efficient in policy management; this is because the existing architecture has the ability to grant a role inheritance by an administrator only. In contrast, the proposed architecture can grant a role inheritance to the administrator and the user.

4.5. Ontology in Business Process Compliance

In [81], the authors developed a framework referred to as an automatic compliance checking framework based on an ontological architecture to design a model to observe the rate of conformity and scrutinize the system in a business information management domain. Their framework incorporates environmental building information and sensors provided the data.

In [78], the authors’ work provides the model for developing a legal framework that considers an expert view of legal privileges. To prove the efficiency of their proposed method, they used a relator and its specialties in terms of the framework they applied.

In [80], the authors’ proposal is an integrated framework that checks compliance with legal rules and emphasizes GDPR. They used Akoma Ntoso to model the text with PrOnto for the legal concepts and LegalRuleML for the norms; they used Regorous to combine BPMN and facts with rules as expressed in LegalRuleML, providing the final report.

In [76], the authors proposed an approach that can check if an enterprise functionality complied with the stated organizational syntax and semantics by examining functions within the ontological functional framework. Again, if this method can specify organizational syntax as a reasoning database with respect to the outsider enterprise model, the system can detect violation using a logic program reasoner.

In [79], the authors proposed a service contract ontology grounded in a legal core ontology referred to as UFO-L and a core ontology of service known as UFO-S. They used the SLA (Service Level Agreement) as the foundation to enhance an already existing organizational language and its framework.

In [77], the authors proposed an architecture for managing compliance using semantic analysis. They intend to save all enterprise functionality, including design time verification, run time, offline, and investigation. Their framework incorporates a unified semantic environment, industry, and governing information for various abstraction nodes that offers a shared conceptualization of related and business-specific compliance.

5. Results and Discussion

Table 4 provides the contributions in terms of the proposed method, practice environment, strengths, and weaknesses of the articles used in the study. As Table 4 shows, the proposed method is ontology. This is due to its semantic capabilities.

Table 4.

Summary of contributions and their weaknesses.

However, few studies explained the usage of ontology in a legacy or traditional computing environment.

As seen in Table 5, the systematic review of the literature summarizes the number of studies related to initiatives. New techniques, processes, and approaches try to facilitate the use of semantic rules to enhance adoption and migration to the cloud; however, studies show that the compliance of the ontology business process with the rich semantic rules is only rarely deployed through the cloud. The area mainly concentrated in the cloud is the issue of security compliance. These features can be used as the basis for new processes, methodologies, and frameworks.

Table 5.

Summary of some selected studies per initiatives.

5.1. Discussion

RQ1:

How has the ontology in cloud computing evolved?

This study has been carried out using a comprehensive review approach of studies that address ontology trends in cloud computing. Our investigation reveals that: Cloud computing has positioned itself as the major technological advancement of the moment, attracting attention from various research areas. It evolved from previous technologies and computing areas like service-oriented architecture (SOA), virtualization, and grid computing. As expected, it comes with its inherent advantages and disadvantages [83]. Cloud computing operations have found expression in semantic web rules. It is common knowledge to see ontology applied in various software engineering environments like Change Control, Process Support, and Requirement Engineering. Most are limited to only web applications [84]. As a concept that must meet the changing needs of software users, it must be maintained constantly and evolve continuously according to the domain or knowledge space [85].

RQ2:

Which Area Has Dominated the Use of Ontology in Cloud Computing?

From Table 5, it is clear that cloud security and compliance have benefited more from ontologies in cloud computing. Especially as security has become an integral aspect of cloud business consolidation, this is based on the distinct groups’ perspectives, including researchers from academia, business policy decision makers, and governmental organizations. The similarities in these various viewpoints provide a clear indication of the crucial nature of security and legal impediments for cloud computing, including data confidentiality, reputation fate sharing, service availability, and provider lock-in.

RQ3:

In which area has the ontology been least deployed in cloud computing?

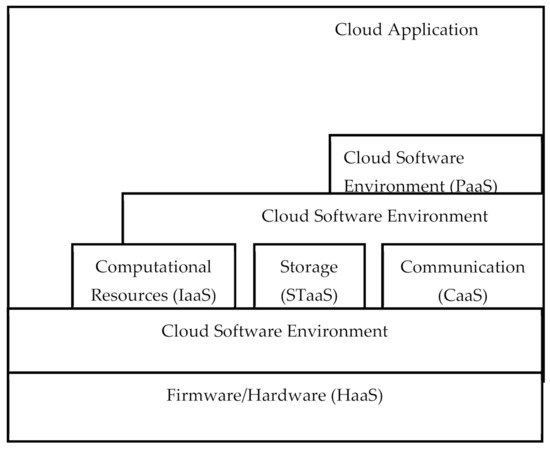

Table 5 shows that ontologies has been the least employed in business process compliance. It is also very clear that ontologies enjoyed relative attention in many software areas in traditional computing. At the same time, that cannot be said for its applications in the cloud. From studies carried out in the course of this work, it is clear that many application areas of software engineering have yet to enter the cloud market; the traditional/legacy applications overshadow them (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cloud ontology: described as five layers, with three components to the cloud infrastructure layer.

RQ4:

Problems and future directions in ontology and cloud research.

The evolution, usage, and deployment approaches of cloud computing provide the basis for the problems and the future directions in ontology and cloud research which are discussed under two broad areas: business process compliance and cloud computing.

5.2. Business Process Compliance

As compliance becomes a major issue, the effect of optimization is thought of as a strategic concern, such that business compliance requirements can be achieved by applying smart audit techniques that can only come from IT knowledge [86].

Traditional audit improves operating efficiency and control. If these controls are improperly placed or malfunctions, the regulators can only analyze a portion of the information. Interestingly, varying information tools and technologies have contributed significantly to improving auditing methods. In this work, we discovered that SOA evaluation is necessary to understand that these enterprise syntaxes improve with phases and require continuous improvement [27]. The intellectual asset involves many aspects; one of them is the ability to perform various tasks. Every process requires special skill set therefore, staff members with the required knowledge would be responsible for such processes. Management’s concern is to understand what information remains embedded and how to abstract these different methods. The process remains flexible; hence, every variation starts at the process [87]. The prospect for which business processes have been introduced to SOA has formed the baseline for areas such as enterprise procedures and implementation semantics that include the organizational method framework, and notations that are typical for computerization and orchestration services for the business processes [88].

5.3. Cloud Computing: A Projection

Verification, including the valuation of cloud components from resistance to reliability, remains a huge challenge. Despite an increase in the figure with respect to current research activities centered on the definition of related quality metrics and benchmarks, no solution has yet been adopted as a standard [89]. At the network edge, there are analytic streams that are implemented to reduce traffic and, in some instances, provide a privacy preservation algorithm. The edge of the IoT is responsible for semantic mediation, which converts data into a format accessible to both humans and machines. In contrast, semantic interoperability is a function of the cloud. In the future, data processing will be performed on every layer of the device edge and cloud. By doing so, the infrastructural dynamism of IoT would be considered. IoT technologies have assumed a necessity status in aiding the transfer of information, which activates automated facilities. The cross of the matter is that they have limitations to the number of services they can support due to resource constraints.

However, fog computing is seen as a veritable alternative to these challenges, as long as it collaborates with the veil system in extending cloud capability towards the verge of the system. With this method, the benefits of the system can be brought closer to the end user [90]. Fog computing is defined as “a horizontal system-level architecture that distributes computing, storage, control, and networking functions closer to users along a cloud-to-thing continuum” [91]. Note that in edge computing, data processing takes place at the network’s edge, near the physical location where the data are created, whereas fog computing functions as a bridge between the edge and the cloud for a variety of reasons, including data filtering.

The fog and cloud operate in a distributed manner to achieve the need for an application [92]. However, some applications require low latency so that distance becomes a barrier [93]. An attempt is being made to rectify the challenges associated with these two concepts. Hence, mist computing was introduced. NIST defines mist computing as “a lightweight and rudimentary form of fog computing that resides at the edge of the network fabric, bringing the fog computing layer closer to the smart end devices”. Mist computing uses microcomputers and microcontrollers to feed into fog computing nodes and potentially onward towards the centralized (cloud) computing services. Devices close to the mist provide the ability to identify and identify points of personal knowledge and point-identification; with this, they can provide a vibrant distribution of information due to environmental variation [94]. It helps to reduce the technological load requirement while also reducing inactivity, thus improving the independence of the result [95]. Table 6 shows the comparison between fog computing and cloud computing.

Table 6.

Comparison of fog computing and cloud computing.

From Table 6, it is obvious that the fog provides an improved benefit than the cloud in most of the parameters. However, they are the same in some of the parameters.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

The inherent advantage associated with ontology is such that, if properly applied to crucial application areas like business-compliant processes, cloud security compliance using the cloud technology would prove huge savings for practitioners. The analysis of the incorporated articles indicates several challenges and areas for future studies. It comprises those particularly connected with ontologies to enhance security and interoperability of cloud transactions. We abridged the selected articles into four key sets: cloud security, cloud resources and service description, cloud service discovery and selection, and cloud interoperability. While a huge impact has been made on cloud computing ontology, there exists a plethora of challenges and issues to be resolved in this domain. Based on the prevailing studies, the study acknowledged some unresolved issues in this domain, such as:

Heterogeneity. This is the basis for inter-operability conflict due mainly to scripting format, which allows different vendors to implement their services in multi-clouds in their own format without adhering to a common template. A standard format is required to provide a viable platform for interaction in a shared understanding and help eliminate vendor lock-ins.

Security. Since information is held in trust by a third party, there is a reason for clarity, especially with the Service Level Agreement (SLA), which specifies the rights and privileges of the cloud customer so that trust could be built to sustain cloud transactions in multi-cloud.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable, the study does not report any data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mell, P.; Grance, T. The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing. Available online: http://faculty.winthrop.edu/domanm/csci411/Handouts/NIST.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, L.; Boutaba, R. Cloud computing: State-of-the-art and research challenges. J. Internet. Serv. Appl. 2010, 1, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E. Conversation with Eric Schmidt Hosted by Danny Sullivan. Search Engine Strategies Conference (2006). Available online: https://www.google.com/press/podium/ses2006.html (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Buzys, R.; Maskeliunas, R.; Damaševičius, R.; Sidekerskiene, T.; Woźniak, M.; Wei, W. Cloudification of virtual reality gliding simulation game. Information 2018, 9, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danevičius, E.; Maskeliunas, R.; Damaševičius, R.; Połap, D.; Wožniak, M. A soft body physics simulator with computational offloading to the cloud. Information 2018, 9, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Luo, Z.; Du, Y.; Guo, L. Cloud Computing: An Overview. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-10665-1_63#citeas (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Odun-Ayo, I.; Misra, S.; Omoregbe, N.; Onibere, E.; Bulama, Y.; Damasevičius, R. Cloud-based security driven human resource management system. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference of the Catalan Association for Artificial Intelligence, Deltebre, Terres de l’Ebre, Spain, 25–27 October 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gazzar, R.; Hustad, E.; Olsen, D.H. Understanding cloud computing adoption issues: A Delphi study approach. J. Syst. Softw. 2016, 118, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara-Martins, J.; Sahandi, R.; Tian, F. Critical analysis of vendor lock-in and its impact on cloud computing migration: A business perspective. J. Cloud Comput. Adv. Syst. Appl. 2016, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odun-Ayo, I.; Geteloma, V.; Misra, S.; Ahuja, R.; Damasevicius, R. Systematic mapping study of utility-driven platforms for clouds. Proc. Int. Conf. Emerg. Trends Inf. Technol. 2020, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androcec, D.; Vrcek, N.; Seva, J. Cloud computing ontologies: A systematic review. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Models and Ontology-based Design of Protocols, Architectures and Services Cloud, Chamonix/Mont Blanc, France, 29 April–4 May 2012; pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sayed, M.M.; Hassan, H.A.; Omara, F.A. Towards evaluation of cloud ontologies. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2019, 126, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimerink, A.A.; Helver, M. Security and compliance ontology for cloud service agreements. Int. J. Cloud Comput. Database Manag. 2020, 1, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, F.S.; Nascimento, M.H.R. Major Challenges Facing Cloud Migration. J. Eng. Technol. Ind. Appl. 2020, 6, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. Cloud Computing Technologies and Applications. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4419-6524-0_2 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Watts, S. SaaS vs PaaS vs IaaS: What’s the Difference and How to Choose. 2017. Available online: https://www.bmc.com/blogs/saas-vs-paas-vs-iaas-whats-the-difference-and-how-to-choose (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Dillon, T.; Wu, C.; Chang, E. Cloud Computing: Issues and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2010 24th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, Perth, Australia, 20–23 April 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T. “What is Ontology?” Encyclopedia of Database Systems 1. Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-0-387-39940-9_1318 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Flahive, A.; Taniar, D.; Rahayu, W. Ontology as a Service (OaaS): A case for sub-ontology merging on the cloud. J. Supercomput. 2011, 65, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfazi, A.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Qin, Y.; Noor, T.H. Ontology-Based Automatic Cloud Service Categorization for Enhancing Cloud Service Discovery. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 19th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 21–25 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tankelevičiene, L.; Damaševičius, R. Towards the development of genuine intelligent ontology-based e-learning systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Systems, Xiamen, China, 29–31 October 2010; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Sim, K.M. Ontology and search engine for cloud computing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on System Science and Engineering, Yichang, Hubei, China, 12–14 November 2010; pp. 276–281. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkelmann, K.; Laurenzi, E.; Martin, A.; Thönssen, B. Ontology-Based Metamodeling. Stud. Syst. Decis. Control 2018, 141, 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sowunmi, O.Y.; Misra, S.; Omoregbe, N.; Damasevicius, R.; Maskeliūnas, R. A semantic web-based framework for information retrieval in E-learning systems. In International Conference on Recent Developments in Science, Engineering and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliyan, N.; Verma, A. Recent Advances in the Evaluation of Ontology Quality. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/recent-advances-in-the-evaluation-of-ontology-quality/215071 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Deng, Q.; Gönül, S.; Kabak, Y.; Gessa, N.; Glachs, D.; Gigante-Valencia, F.; Thoben, K.D. An ontology framework for multisided platform interoperability. In Enterprise Interoperability VIII; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Gábor, A.; Kő, A.; Szabó, Z.; Fehér, P. Corporate Knowledge Discovery and Organizational Learning: The Role, Importance, and Application of Semantic Business Process Management—The ProKEX Case. In Knowledge Management and Organizational Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini, C.; Calabró, A.; Marchetti, E. GDPR and business processes. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Applications of Intelligent Systems, New York, NY, USA, 7–9 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino, B.; Marino, A.; Rak, M.; Pariso, P. Optimization and Validation of e-Government Business Processes with Support of Semantic Techniques. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-22354-0_76#citeas (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Fan, S.; Hua, Z.; Storey, V.C.; Zhao, J.L. A process ontology based approach to easing semantic ambiguity in business process modeling. Data Knowl. Eng. 2016, 102, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, M.; Governatori, G.; Wynn, M.T. Normative requirements for regulatory compliance: An abstract formal framework. Inf. Syst. Front. 2015, 18, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, K.; Gaaloul, W.; Cuccuru, A.; Gerard, S. Semantic Framework for Internet of Things-Aware Business Process Development. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 26th International Conference on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises (WETICE), Poznan, Poland, 21–23 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, S.; Vateva-Gurova, T.; Trapero, R.; Suri, N. Threat Modeling the Cloud: An Ontology Based Approach. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 11398, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Arogundade, O.T.; Jin, Z.; Yang, X. Towards ontological approach to eliciting risk-based security requirements. Int. J. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2014, 6, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Adesemowo, A.K.; von Solms, R.; Botha, R.A. ITAOFIR: IT asset ontology for information risk in knowledge economy and beyond. In Communications in Computer and Information Science (Global Security, Safety and Sustainability-The Security Challenges of the Connected World); Jahankhani, H., Carlile, A., Emm, D., Hosseinian-Far, A., Brown, G., Sexton, G., Jamal, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: London, UK, 2017; Volume 630, pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Sunkle, S.; Kholkar, D.; Kulkarni, V. Toward Better Mapping between Regulations and Operational Details of Enterprises Using Vocabularies and Semantic Similarity. Complex Syst. Inform. Modeling Q. CSIMQ 2016, 5, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mustapha, A.M.; Arogundade, O.T.; Misra, S.; Damasevicius, R.; Maskeliunas, R. A systematic literature review on compliance requirements management of business processes. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2020, 11, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, M.; Pattanayak, B.K.; Patra, M.R. A Multi-Agent-Based Framework for Cloud Service Description and Discovery Using Ontology. Intell. Comput. Commun. Devices 2014, 308, 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Subhani, N.; Kent, R.D. Continuous process auditing (CPA): An audit rule ontology based approach to audit-as-a-service. In Proceedings of the 2015 Annual IEEE Systems Conference (SysCon) Proceedings, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–16 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Parhi, M.; Pattanayak, B.K.; Patra, M.R. A multi-agent-based framework for cloud service discovery and selection using ontology. Serv. Oriented Comput. Appl. 2017, 12, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageed, Z.S.; Ibrahim, R.K.; Sadeeq, M.A.M. Unified Ontology Implementation of Cloud Computing for Distributed Systems. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenz, S.; Neubauer, T. Ontology-based information security compliance determination and control selection on the example of ISO 27002. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2018, 26, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, M.; Pattanayak, B.K.; Patra, M.R. An ontology-based cloud infrastructure service discovery and selection system. Int. J. Grid Util. Comput. 2018, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.C.; Lim-Cheng, N.R. An ontology based framework to support multi-standard compliance for an enterprise. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (ICRIIS), Langkawi, Malaysia, 16–17 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, N.K.; RS, R.K. Fuzzy service conceptual ontology system for cloud service recommendation. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 69, 435–446. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, D.C.; Villamarin, J.B.; Cu, G.; Lim-Cheng, N.R. Towards Compliance Management Automation thru Ontology mapping of Requirements to Activities and Controls. In Proceedings of the 2018 Cyber Resilience Conference (CRC), Putrajaya, Malaysia, 13–15 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, N.S.; Indulska, M.; Sadiq, S. Compliance management ontology–a shared conceptualization for research and practice in compliance management. Inf. Syst. Front. 2016, 18, 995–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Keele UK Keele Univ. 2004, 33, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Androcec, D.; Vrcek, N. Ontologies for Platform as Service APIs Interoperability. Cybern. Inf. Technol. 2016, 16, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassiliades, N.; Symeonidis, M.; Gouvas, P.; Kontopoulos, E.; Meditskos, G.; Vlahavas, I. PaaSport semantic model: An ontology for a platform-as-a-service semantically interoperable marketplace. Data Knowl. Eng. 2018, 113, 81–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.P.; Elluri, L.; Nagar, A. An Integrated Knowledge Graph to Automate Cloud Data Compliance. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 148541–148555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afgan, E.; Lonie, A.; Taylor, J.; Goonasekera, N. CloudLaunch: Discover and deploy cloud applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 94, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shamsuddin, S.M.; Eassa, F.E.; Mohammed, F. Cloud Service Discovery and Extraction: A Critical Review and Direction for Future Research. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-99007-1_28#citeas (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Modi, K.J.; Garg, S. A QoS-based approach for cloud-service matchmaking, selection and composition using the Semantic Web. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2019, 21, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, F.; Asadabadi, M.R.; Janjua, N.K.; Hussain, O.K.; Chang, E.; Saberi, M. An MCDM method for cloud service selection using a Markov chain and the best-worst method. Knowl. Based Syst. 2018, 159, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbodio, M.L.; Martin, D.; Moulin, C. Discovering Semantic Web services using SPARQL and intelligent agents. J. Web Semant. 2010, 8, 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, B.; Cretella, G.; Esposito, A. Cloud services composition through cloud patterns: A semantic-based approach. Soft Comput. 2016, 21, 4557–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, F.; Mohsin, A.; Janjua, N.K. Service description languages in cloud computing: State-of-the-art and research issues. Serv. Oriented Comput. Appl. 2019, 13, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhi, A.; Fortineau, V.; Huet, J.C.; Lamouri, S. Ontology for cloud manufacturing based Product Lifecycle Management. J. Intell. Manuf. 2017, 30, 2171–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.C.S. A Web Services, Ontology and Big Data Analysis Technology-Based Cloud Case-Based Reasoning Agent for Energy Conservation of Sustainability Science. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, X. ManuService ontology: A product data model for service-oriented business interactions in a cloud manufacturing environment. J. Intell. Manuf. 2016, 30, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwell, R.; Liu, X.; Chalmers, K.; Pahl, C. Task Orientated Requirements Ontology for Cloud Computing Services. Available online: https://www.scitepress.org/papers/2016/57523/57523.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Brogi, A.; Ferrari, G.L.; Forti, S. Secure Cloud-Edge deployments, with trust. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 102, 775–788. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, C.; Choi, J. Ontology-based Security Context Reasoning for Power IoT-Cloud Security Service. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 110510–110517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Choi, J.; Kim, P. Ontology-based access control model for security policy reasoning in cloud computing. J. Supercomput. 2013, 67, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, F.D.F.; Jino, M. A Survey of security assessment ontologies. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Di, M. Design of the Network Security Intrusion Detection System Based on the Cloud Computing. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15235-2_11 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Janulevicius, J.; Marozas, L.; Cenys, A.; Goranin, N.; Ramanauskaite, S. Enterprise architecture modeling based on cloud computing security ontology as a reference model. In Proceedings of the 2017 Open Conference of Electrical, Electronic and Information Sciences (eStream), Vilnius, Lithuania, 27 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaiprasath, R.; Elankavi, R.; Udayakumar, R. Cloud security and compliance -a semantic approach in end to end security. Available online: https://www.exeley.com/in_jour_smart_sensing_and_intelligent_systems/doi/10.21307/ijssis-2017-265 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Klimenko, A.; SafronenkovaI, I. An Ontology-Based Approach to the Workload Distribution Problem Solving in Fog-Computing Environment. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-19810-7_7#citeas (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Singh, V.; Pandey, S.K. Cloud security ontology (CSO). In Cloud Computing for Geospatial Big Data Analytics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 81–109. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Pandey, S.K. A comparative study of Cloud Security Ontologies. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization, Noida, India, 8–10 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, M.; Zuo, J.; Liu, Z.; Castiglione, A.; Palmieri, F. Multi-layer cloud architectural model and ontology-based security service framework for IoT-based smart homes. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 78, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Mazzeo, A.; Moscato, V.; Picariello, A. A Framework for Semantic Interoperability over the Cloud. In Proceedings of the 2013 27th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops, Barcelona, Spain, 25–28 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Castañé, G.C.; Xiong, H.; Dong, D.; Morrison, J.P. An ontology for heterogeneous resources management interoperability and HPC in the cloud. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 88, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corea, C.; Delfmann, P. Detecting Compliance with Business Rules in Ontology- Based Process Modeling. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik, St. Gallen, Switzerland, 12–15 February 2017; pp. 226–240. [Google Scholar]

- Elgammal, A.; Turetken, O. Lifecycle Business Process Compliance Management: A Semantically-Enabled Framework. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Cloud Computing (ICCC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 26–29 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Griffo, C.; Almeida, J.P.A.; Guizzardi, G. Conceptual Modeling of Legal Relations. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2018, 11157, 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Griffo, C.; Almeida, J.P.A.; Guizzardi, G.; Nardi, J.C. From an Ontology of Service Contracts to Contract Modeling in Enterprise Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 21st International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference (EDOC), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 10–13 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Palmirani, M.; Governatori, G. Modelling Legal Knowledge for GDPR Compliance Checking. Available online: https://ebooks.iospress.nl/volumearticle/50839 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Zhong, B.; Wu, H.; Sepasgozar, H.L.S.; Luo, H.; He, L. A scientometric analysis and critical review of construction related ontology research. Autom. Constr. 2019, 101, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaševičius, R. Ontology of domain analysis concepts in software system design domain. In Information Systems Development: Towards a Service Provision Society. Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youseff, L.; Butrico, M.; da Silva, D. Toward a Unified Ontology of Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the Grid Computing Environments Workshop, Austin, TX, USA, 12–16 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, M.P.S.; Kumar, A.; Beniwal, R. Ontologies for Software Engineering: Past, Present and Future. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Osborne, F.; Motta, E. Pragmatic Ontology Evolution: Reconciling User Requirements and Application Performance. Semant. Web–ISWC 2018, 11136, 495–512. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhsh, F.A.; Silva, P.d.; Bukhsh, B.A.; Syed, S. From Traditional to Technologically Influenced Audit: A Compliance Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology (FIT), Islamabad, Pakistan, 17–19 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrogio, A.; Paglia, E.; Bocciarelli, P.; Giglio, A. To-wards performance-oriented perfective evolution of BPMN models. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Theory of Modeling and Simulation (TMS-DEVS), Pasadena, CA, USA, 3–6 April 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Casalicchio, E.; Cardellini, V.; Interino, G.; Palmirani, M. Research challenges in legal-rule and QoS-aware cloud service brokerage. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 78, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puliafito, C.; Mingozzi, E.; Longo, F.; Puliafito, A.; Rana, O. Fog Computing for the Internet of Things. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2019, 19, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenFog Consortium. OpenFog Reference Architecture for Fog Computing. 2017. Available online: https://www.openfogconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/OpenFog_Reference_Architecture_2_09_17-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2019).

- Rubio-Drosdov, E.; Sanchez, D.D.; Almenarez, F.; Marin, A. A Framework for Efficient and Scalable Service Offloading in the Mist. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 5th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Limerick, Ireland, 15–18 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Venčkauskas, A.; Morkevicius, N.; Jukavičius, V.; Damaševičius, R.; Toldinas, J.; Grigaliūnas, Š. An edge-fog secure self-authenticable data transfer protocol. Sensors 2019, 19, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preden, S.; Tammemae, K.; Jantsch, A.; Leier, M.; Riid, A.; Calis, E. The Benefits of Self-Awareness and Attention in Fog and Mist Computing. Computer 2015, 48, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, G.; Bade, D.; Lamersdorf, W. Computing at the mobile edge: Designing elastic android applications for computation offloading. In Proceedings of the 2015 8th IFIP Wireless and Mobile Networking Conference (WMNC), Munich, Germany; 2015; pp. 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Laghari, A.A.; Karim, S.; Shakir, M.; Brohi, A.A. Comparison of Fog Computing Cloud Computing. Int. J. Math. Sci. Comput. (IJMSC) 2019, 5, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).