Well-Being and Social Media: A Systematic Review of Bergen Addiction Scales

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method and Procedures

2.1. Measuring Facebook and Social Media Addiction

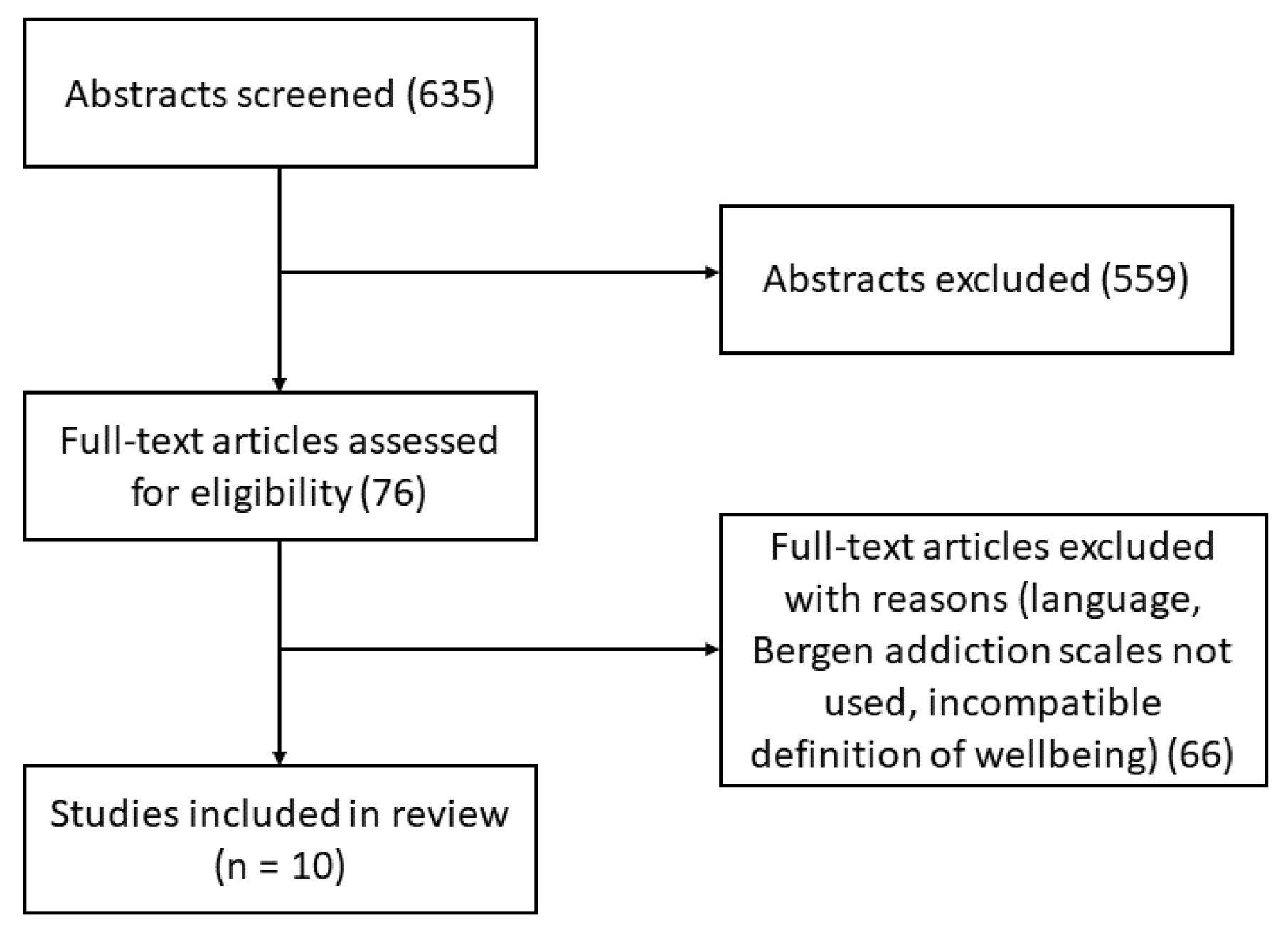

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results: Facebook and Social Media Addiction Effects on Well-Being

3.1. Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being

3.2. Other Well-Being Measures

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krasnova, H.; Abramova, O.; Notter, I.; Baumann, A. Why phubbing is toxic for your relationship: understanding the role of smartphone jealousy among “generation y” users. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1130&context=ecis2016_rp (accessed on 20 November 2016).

- Ling, R. The Mobile Connection: The Cell Phone’s Impact on Society; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M. Online Social Networking and Addiction—A Review of the Psychological Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2011, 8, 3528–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.A.; Ryan, T.; Gray, D.L.; McInerney, D.M.; Waters, L. Social Media Use and Social Connectedness in Adolescents: The Positives and the Potential Pitfalls. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 31, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Billieux, J.; Griffiths, M.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Mazzoni, E.; Pallesen, S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016, 30, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misoch, S. Stranger on the internet: Online self-disclosure and the role of visual anonymity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Pu, J.; Lawrence, G. The Role of Virtual Social Identity through Blog Use in Social Life. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2038&context=amcis2006 (accessed on 23 December 2006).

- Ryan, T.; Chester, A.; Reece, J.; Xenos, S. The uses and abuses of Facebook: A review of Facebook addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.W.; Tran, B.X.; Le, H.T.; Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, C.T.; Tran, T.D.; Latkin, C.A.; Ho, R.C. Perceptions of Health-Related Information on Facebook: Cross-Sectional Study Among Vietnamese Youths. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2017, 6, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guazzini, A.; Duradoni, M.; Capelli, A.; Meringolo, P. An Explorative Model to Assess Individuals’ Phubbing Risk. Future Internet 2019, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Time Spent on Social Network Sites and Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosecky, J.; Hong, D.; Shen, V.Y. User identification across multiple social networks. In Proceedings of the 2009 First International Conference on Networked Digital Technologies, Ostrava, Czech Republic, 29–31 July 2009; pp. 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turel, O.; Brevers, D.; Bechara, A. Time distortion when users at-risk for social media addiction engage in non-social media tasks. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 97, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Gaskin, J.; Wang, H.-Z.; Liu, D. Life satisfaction moderates the associations between motives and excessive social networking site usage. Addict. Res. Theory 2016, 24, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R.C.; Zhang, M.W.; Tsang, T.Y.; Toh, A.H.; Pan, F.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, C.; Yip, P.S.; Lam, L.T.; Lai, C.-M.; et al. The association between internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Turel, O.; Brevers, D.; Bechara, A. Excess social media use in normal populations is associated with amygdala-striatal but not with prefrontal morphology. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2017, 269, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.; Pontes, H.M. Chaos and confusion in DSM-5 diagnosis of Internet Gaming Disorder: Issues, concerns, and recommendations for clarity in the field. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 6, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.-K.; Lai, C.-M.; Ko, C.-H.; Chou, C.; Kim, D.-I.; Watanabe, H.; Ho, R.C.M. Psychometric Properties of the Revised Chen Internet Addiction Scale (CIAS-R) in Chinese Adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.X.; Mai, H.T.; Nguyen, L.H.; Nguyen, C.T.; Latkin, C.A.; Zhang, M.W.B.; Ho, R.C.M. Vietnamese validation of the short version of Internet Addiction Test. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2017, 6, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turel, O.; Qahri-Saremi, H. Problematic use of social networking sites: antecedents and consequence from a dual-system theory perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 33, 1087–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.X.; Huong, L.T.; Hinh, N.D.; Nguyen, L.H.; Le, B.N.; Nong, V.M.; Thuc, V.T.M.; Tho, T.D.; Latkin, C.; Zhang, M.W.; et al. A study on the influence of internet addiction and online interpersonal influences on health-related quality of life in young Vietnamese. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Torsheim, T.; Brunborg, G.S.; Pallesen, S. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 110, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Griffiths, M. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longstreet, P.; Brooks, S. Life satisfaction: A key to managing internet & social media addiction. Technol. Soc. 2017, 50, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.Y.; Sidani, J.E.; Shensa, A.; Radovic, A.; Miller, E.; Colditz, J.B.; Hoffman, B.L.; Giles, L.M.; Primack, B.A. Association Between Social Media Use and Depression Among U.s. Young Adults. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kross, E.; Verduyn, P.; Demiralp, E.; Park, J.; Lee, D.S.; Lin, N.; Shablack, H.; Jonides, J.; Ybarra, O. Facebook Use Predicts Declines in Subjective Well-Being in Young Adults. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e69841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M. Internet addiction: Fact or fiction? The Psychologist 1999, 12, 246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, M.; Kuss, D.J.; Billieux, J.; Pontes, H.M. The evolution of Internet addiction: A global perspective. Addict. Behav. 2016, 53, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampe, C.; Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C. Changes in Use and Perception of Facebook. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2008 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 721–730. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.; Fornasier, S.; White, K.M. Psychological Predictors of Young Adults’ Use of Social Networking Sites. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, 13, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. Nicotine, tobacco and addiction. Nature 1996, 384, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.-H. Internet Gaming Disorder. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2014, 1, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.; Karila, L.; Billieux, J. Internet Addiction: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Research for the Last Decade. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ben/cpd/2014/00000020/00000025/art00006 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. A Meta-analysis of Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z. Chapter 6 - Social Networking Addiction: An Overview of Preliminary Findings. In Behavioral Addictions; Rosenberg, K.P., Feder, L.C., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kircaburun, K.; Griffiths, M.D. Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, D. The WHO Definition of “Health”. Hastings Cent. Stud. 1973, 1, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alheneidi, H. The influence of information overload and problematic Internet use on adults’ well-being. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Atroszko, P.A.; Balcerowska, J.M.; Bereznowski, P.; Biernatowska, A.; Pallesen, S.; Schou Andreassen, C. Facebook addiction among Polish undergraduate students: Validity of measurement and relationship with personality and well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Teismann, T.; Margraf, J. Physical activity mediates the association between daily stress and Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) – A longitudinal approach among German students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; van Koningsbruggen, G.M.; Kerkhof, P. A brief measure of social media self-control failure. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufadi, Y. Social networking time use scale (SONTUS): A new instrument for measuring the time spent on the social networking sites. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, S.A. Facebook Addiction and Subjective Well-Being: a Study of the Mediating Role of Shyness and Loneliness. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, S.A.; Uysal, R. Well-being and problematic Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 49, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turel, O.; Poppa, N.; Tasha; Gil-Or, O. Neuroticism Magnifies the Detrimental Association between Social Media Addiction Symptoms and Wellbeing in Women, but Not in Men: A three-Way Moderation Model. Psychiatr. Q. 2018, 89, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, J.D.; Mansfield, R.; Corcoran, R. Attachment Anxiety and Problematic Social Media Use: The Mediating Role of Well-Being. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Prieto, C.; Diener, E.; Tamir, M.; Scollon, C.; Diener, M. Integrating The Diverse Definitions of Happiness: A Time-Sequential Framework of Subjective Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2005, 6, 261–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A.; Baylis, N.; Keverne, B.; Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H.; Dienberg Love, G. Positive health: connecting well–being with biology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. Psychological Well-Being: Meaning, Measurement, and Implications for Psychotherapy Research. Psychother. Psychosom. 1996, 65, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. What Is Positive about Positive Psychology: The Curmudgeon and Pollyanna. Psychol. Inq. 2003, 14, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.S.; Schwartz, S.J.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Ravert, R.D.; Williams, M.K.; Agocha, V.B.; Kim, S.Y.; Donnellan, M.B. The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. J. Posit. Psychol. 2010, 5, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New Well-being Measures: Short Scales to Assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A.; So, T.T.C. Flourishing Across Europe: Application of a New Conceptual Framework for Defining Well-Being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 110, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being; Atria Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, C.; Hervás, G.; Ho, S.M.Y. Intervenciones clínicas basadas en la Psicología Positiva: Fundamentos y aplicaciones. Psicol. Conduct. 2006, 14, 401–432. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle, D.E.; Wiersma, W.; Jurs, S.G. Applied statistics for the behavioral sciences, 5th ed.; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-495-80885-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Lepper, H.S. A Measure of Subjective Happiness: Preliminary Reliability and Construct Validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C. On Energy, Personality, and Health: Subjective Vitality as a Dynamic Reflection of Well-Being. J. Pers. 1997, 65, 529–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O’Connell, K.A. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atroszko, P.A.; Andreassen, C.S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pallesen, S. Study addiction — A new area of psychological study: Conceptualization, assessment, and preliminary empirical findings. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, R.E. Activation-Deactivation Adjective Check List: Current Overview and Structural Analysis. Psychol. Rep. 1986, 58, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Biswas-Diener, R.; King, L.A. Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukat, J.; Margraf, J.; Lutz, R.; van der Veld, W.M.; Becker, E.S. Psychometric properties of the Positive Mental Health Scale (PMH-scale). BMC Psychol. 2016, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.M.; Pendlebury, H.; Thomas, K.; Smith, A.P. The Student Wellbeing Process Questionnaire (Student WPQ). Psychology 2017, 8, 1748–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.; Smith, A.P. A holistic approach to stress and well-being. Part 6: The Wellbeing Process Questionnaire (WPQ Short Form). Occup. Health Work 2012, 9, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, M.; Dutton, W.H. Society and the Internet: How Networks of Information and Communication are Changing Our Lives; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Monacis, L.; de Palo, V.; Griffiths, M.D.; Sinatra, M. Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awata, S.; Bech, P.; Yoshida, S.; Hirai, M.; Suzuki, S.; Yamashita, M.; Ohara, A.; Hinokio, Y.; Matsuoka, H.; Oka, Y. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index in the context of detecting depression in diabetic patients. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 61, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, M.; Hayashino, Y.; Tsujii, S.; Ishii, H.; Fukuhara, S. Comparative validity of the WHO-5 Well-Being Index and two-question instrument for screening depressive symptoms in patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2013, 50, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.S. Internet Addiction: A New Clinical Phenomenon and Its Consequences. Am. Behav. Sci. 2004, 48, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hone, L.; Jarden, A.; Schofield, G. Psychometric Properties of the Flourishing Scale in a New Zealand Sample. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, M.; Senol-Durak, E.; Gencoz, T. Psychometric Properties of the Satisfaction with Life Scale among Turkish University Students, Correctional Officers, and Elderly Adults. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 99, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Barkley, J.E.; Karpinski, A.C. The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and Satisfaction with Life in college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunz, U.; Curry, C.; Voon, W. Perceived versus actual computer-email-web fluency. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 2321–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.J. Technological literacy: A multliteracies approach for democracy. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2009, 19, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastin, M.S.; LaRose, R. Internet Self-Efficacy and the Psychology of the Digital Divide. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2000, 6, JCMC611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Haridakis, P.M. The Role of Internet User Characteristics and Motives in Explaining Three Dimensions of Internet Addiction. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2009, 14, 988–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamberini, L.; Luciano; Alcañiz Raya, M.; Mariano; Barresi, G.; Giacinto; Fabregat; Malena; Ibanez; Gonçalves, F.; et al. Cognition, technology and games for the elderly: An introduction to ELDERGAMES Project. PsychNol. J. 2006, 4, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Kirman, B.; Lawson, S.; Linehan, C.; Martino, F.; Gamberini, L.; Gaggioli, A. Improving Social Game Engagement on Facebook Through Enhanced Socio-contextual Information. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1753–1756. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolli, A.; Corradi, N.; Gamberini, L.; Hoggan, E.; Jacucci, G.; Katzeff, C.; Broms, L.; Jonsson, L. Eco-Feedback on the Go: Motivating Energy Awareness. Computer 2011, 44, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Author | Year | Country | Sample Size | Sample Description | Measure of WB | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS) | |||||||

| 1 | Turel and Gil-Or | 2018 | Israel | 215 | Israeli college students (age range: 20–65; M-age = 26.99) | WHO five item Wellbeing Index (WHO-5; [72]) | −0.57 ** |

| 2 | Satici and Uysal | 2015 | Turkey | 311 | Turkey university students (age range: 18–32; M-age = 20.86 years) | The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; [60]) | −0.32 ** |

| Flourishing Scale [62] | −0.29 ** | ||||||

| Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; [67]) | −0.32 ** | ||||||

| Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS; [68]) | −0.32 ** | ||||||

| 3 | Atroszko, Balcerowska, Bereznowski, Biernatowsk, Pallesen, and Andreassen | 2018 | Poland | 1157 | Gdańsk full-time university students (M-age =20.33 years) | Adapted WHOQOL Brief scale - Quality of life [70] | −0.07 * |

| 4 | Wang, Gaskin, Wang and Liu | 2016 | China | 915 | College students China (M-age = 19.87) | Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; [60]) | −0.11 ** (excessive user of Weibo) 0.05 (non-excessive users) |

| 5 | Satici | 2019 | Turkey | 280 | University students (range 17–25; M-age = 21.04 years) | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; [61]) | Range from −0.13 ** to −0.18 ** |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; [60]) | Range from −0.16 ** to −0.21 ** | ||||||

| 6 | Brailovskaia, Teismann, and Margraf | 2018 | Germany | 122 | German college students that were Facebook users (age range: 17–38) | Positive Mental Health Scale (PMH-Scale; [74]) | −0.27 ** |

| 7 | Du, van Koningsbruggen and Kerkhof | 2018 | US, UK, Canada, and Australia | 405 | Prolific platform users. Age range: 18–59 years; M-age=31; | Activation Deactivation Adjective Checklist (ADACL; [71]) | −0.10 * |

| 8 | Olufadi | 2016 | Nigeria | 1808 | People from Ilorin metropolis. Age range: 20–58; M-age = 32.43 | Positive relations with others [76] | −0.13 * |

| Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) | |||||||

| 9 | Worsley, Mansfield, and Corcoran | 2018 | Not available, online survey | 915 | Social media users. Age range: 18–25; M-age = 20.19 | 18-item version of Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWBSs; [76]) | −0.34 ** |

| 10 | Alheneidi | 2019 | UK | 226 | UK-based students (age range: 18–71) | The Student WPQ [75]: positive well-being | −0.13 * |

| The Student WPQ: negative well-being | 0.28 ** | ||||||

| UK | 254 | UK-based employees (age range: 18–65; M-age=42) | WPQ short form [78]: Positive well-being | 0.04 | |||

| WPQ short form: Negative well-being | 0.45 ** | ||||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duradoni, M.; Innocenti, F.; Guazzini, A. Well-Being and Social Media: A Systematic Review of Bergen Addiction Scales. Future Internet 2020, 12, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12020024

Duradoni M, Innocenti F, Guazzini A. Well-Being and Social Media: A Systematic Review of Bergen Addiction Scales. Future Internet. 2020; 12(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuradoni, Mirko, Federico Innocenti, and Andrea Guazzini. 2020. "Well-Being and Social Media: A Systematic Review of Bergen Addiction Scales" Future Internet 12, no. 2: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12020024

APA StyleDuradoni, M., Innocenti, F., & Guazzini, A. (2020). Well-Being and Social Media: A Systematic Review of Bergen Addiction Scales. Future Internet, 12(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12020024