Machine Learning-Guided Development of Anti-Tuberculosis Dry Powder for Inhalation Prepared by Co-Spray Drying

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

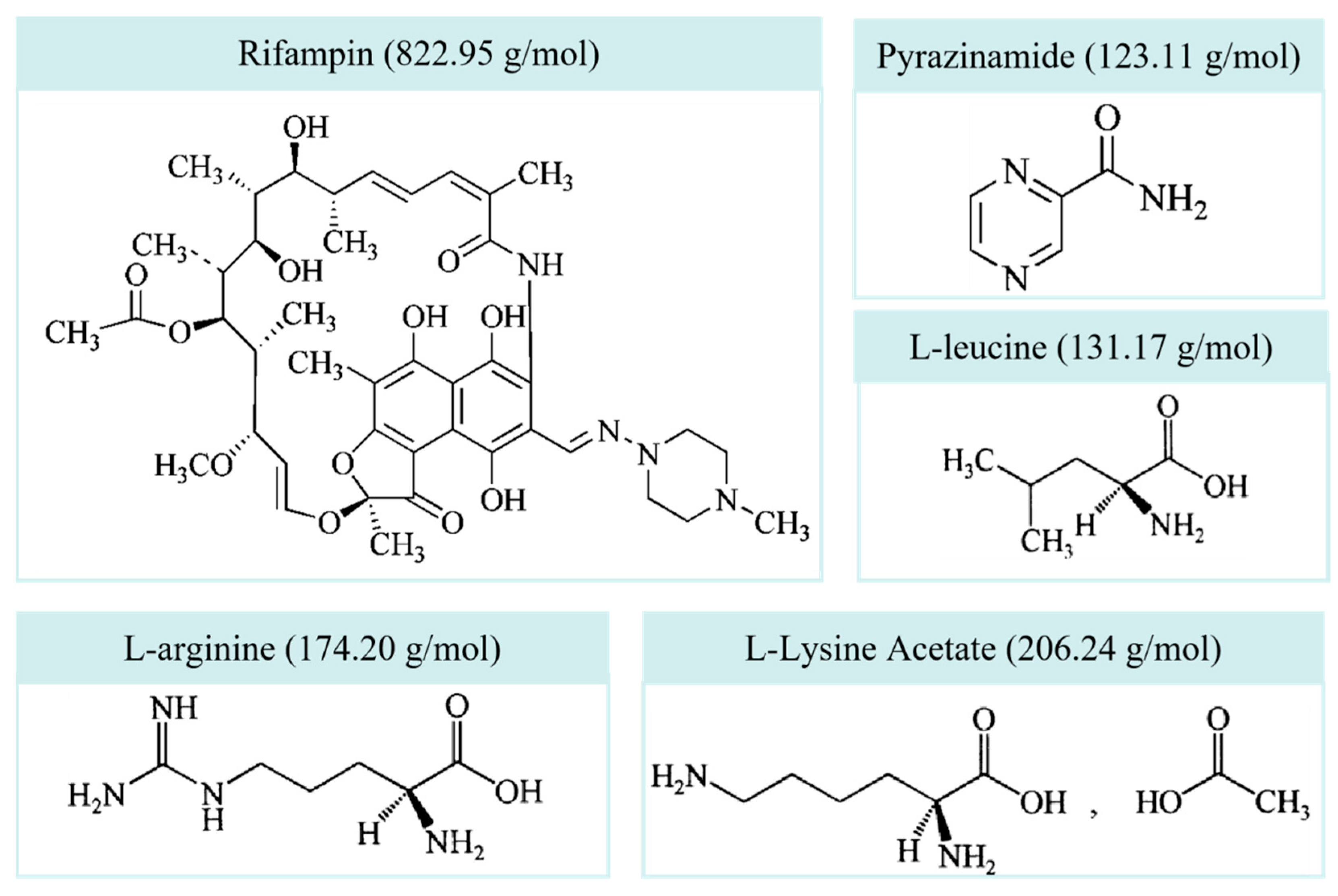

2.1. Materials

2.2. Spray Drying

2.3. In Vitro Aerodynamic Performance

2.4. Physicochemical Characterization

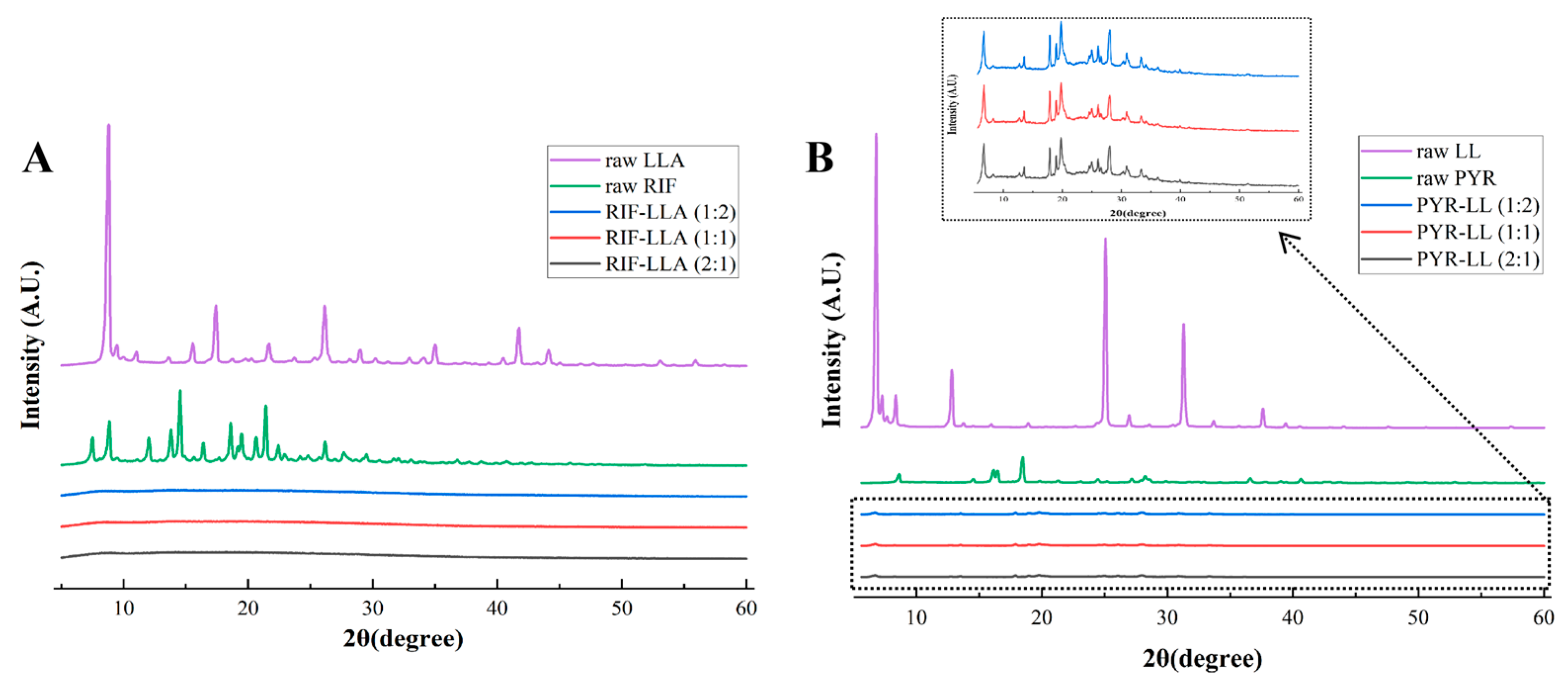

2.4.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

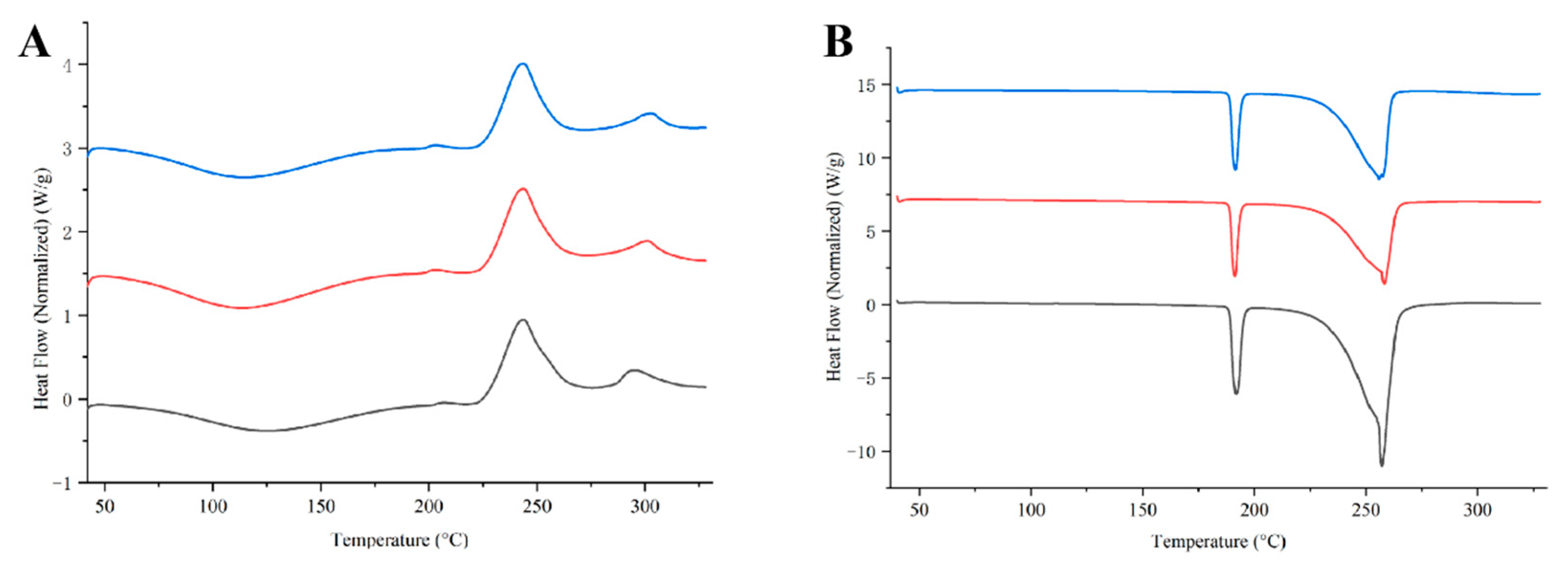

2.4.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

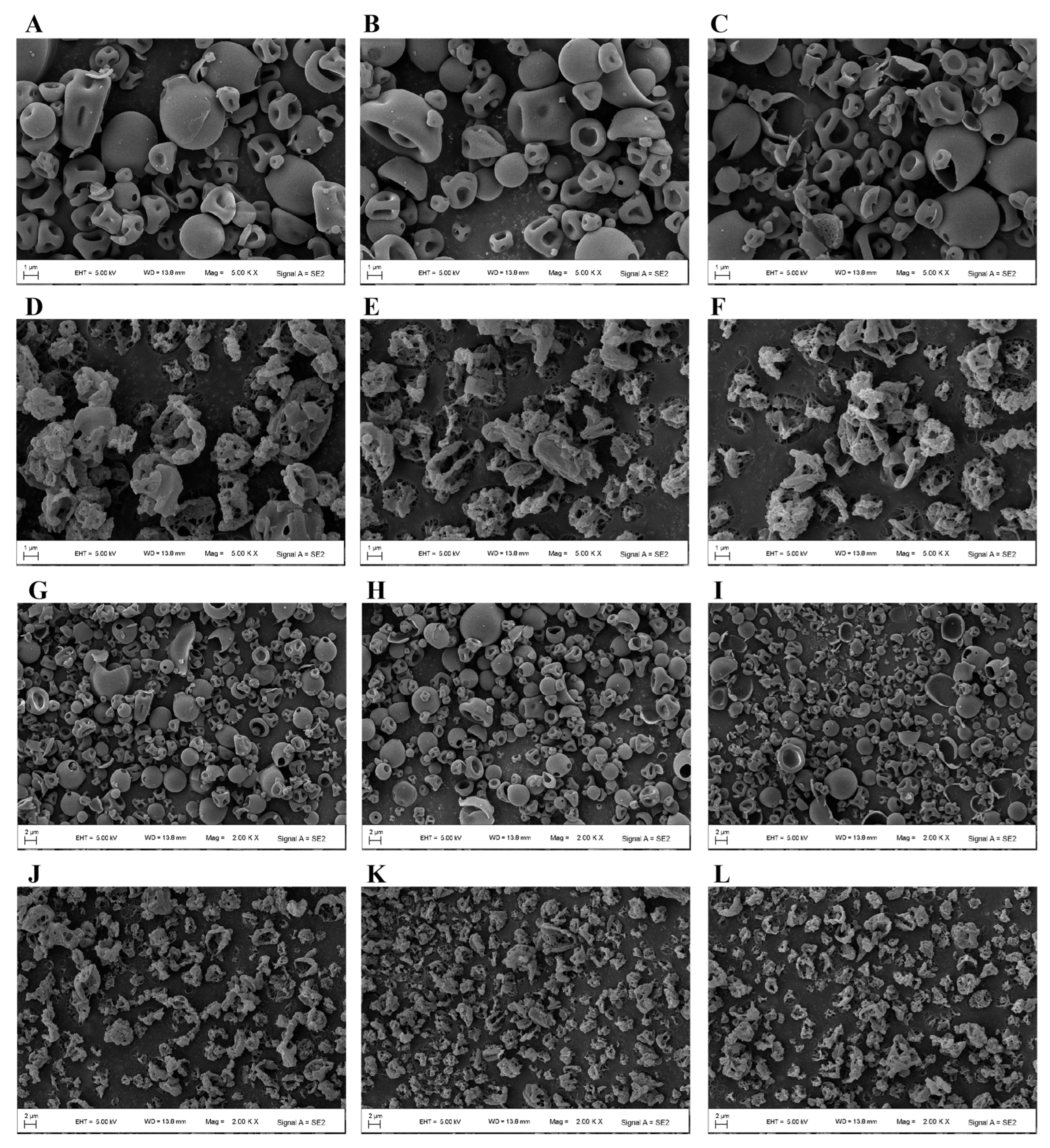

2.4.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.5. Machine Learning Model Development

2.5.1. Data Preparation

2.5.2. Model Construction

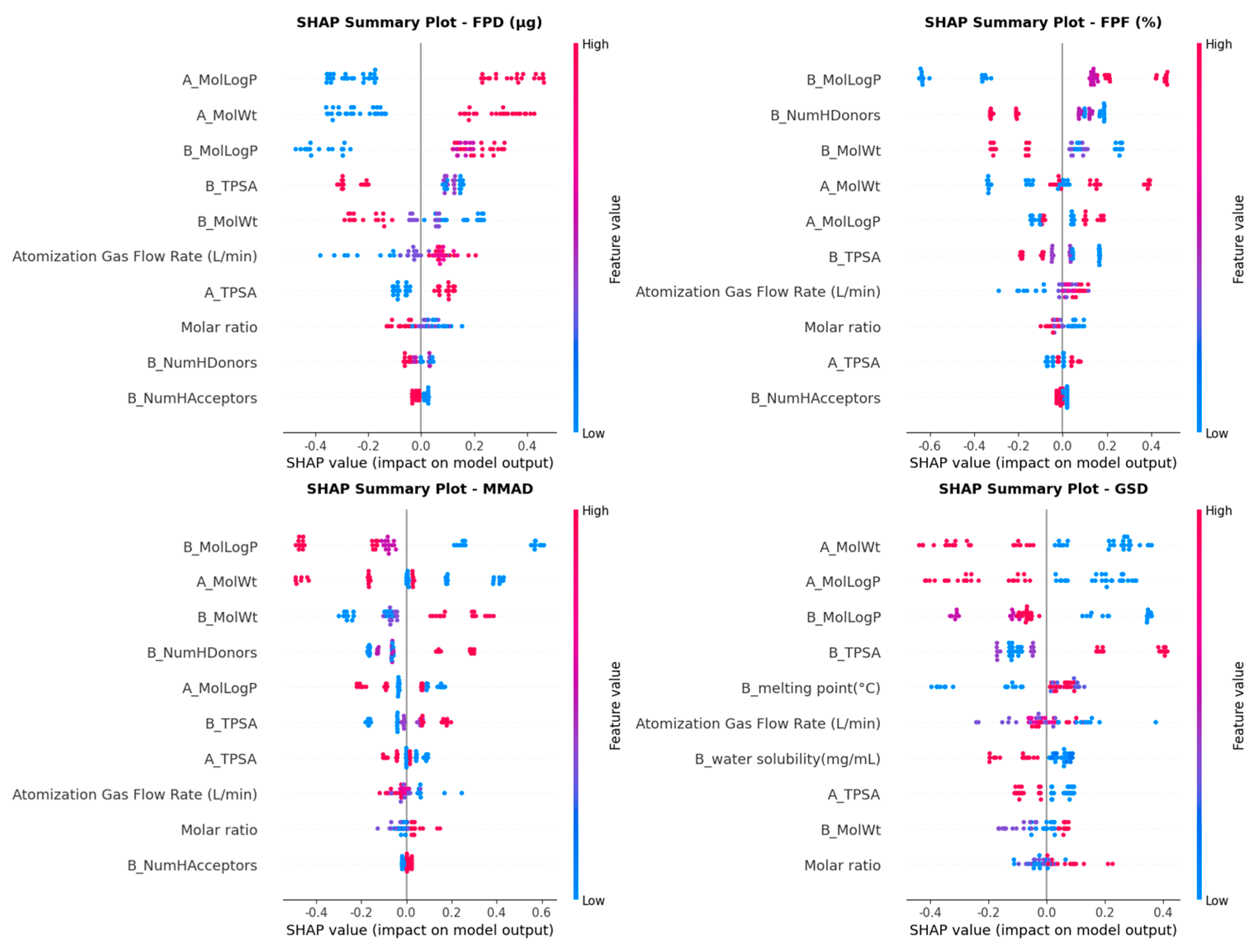

2.5.3. Evaluation Criteria and Interpretability

3. Results

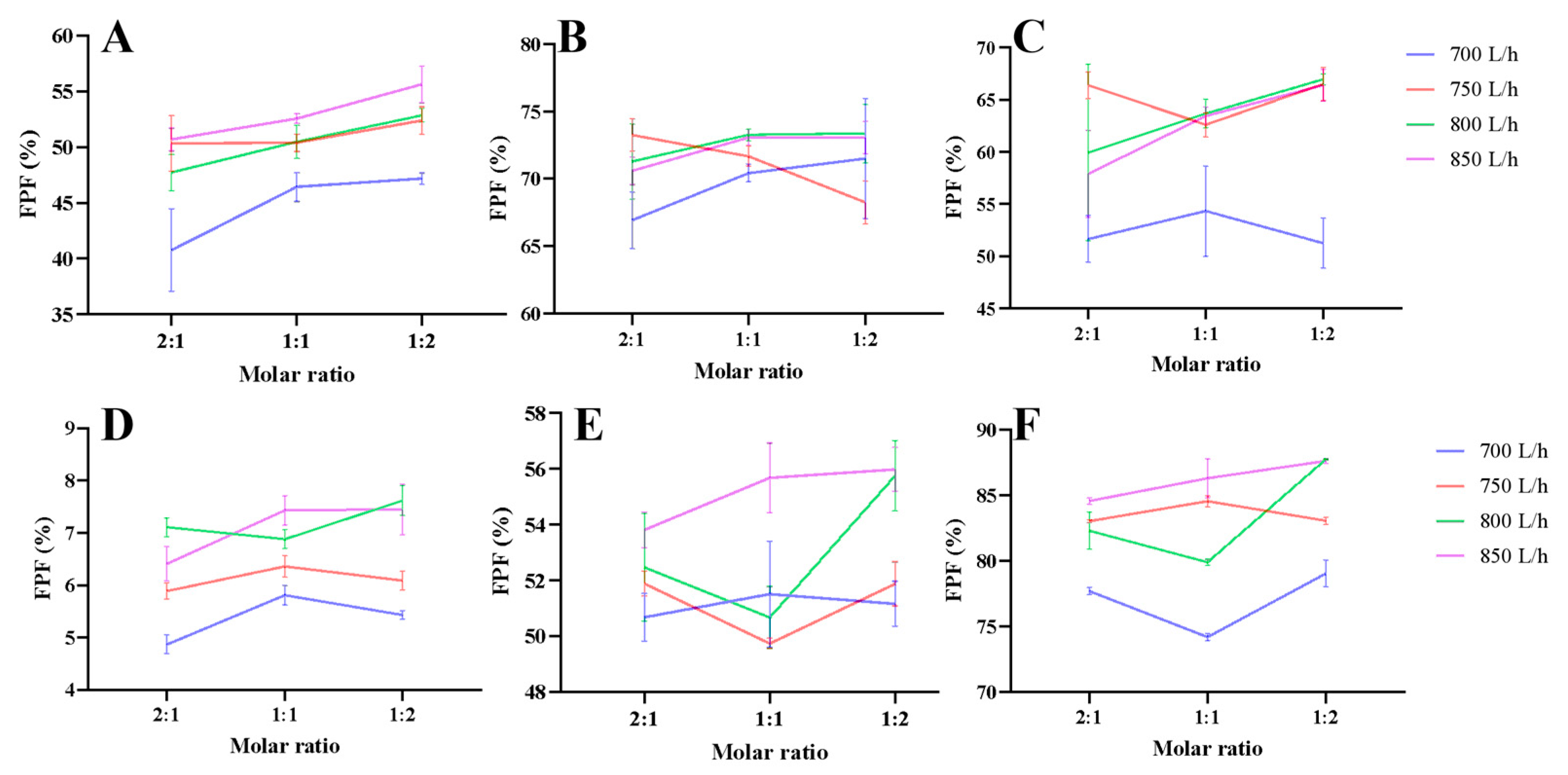

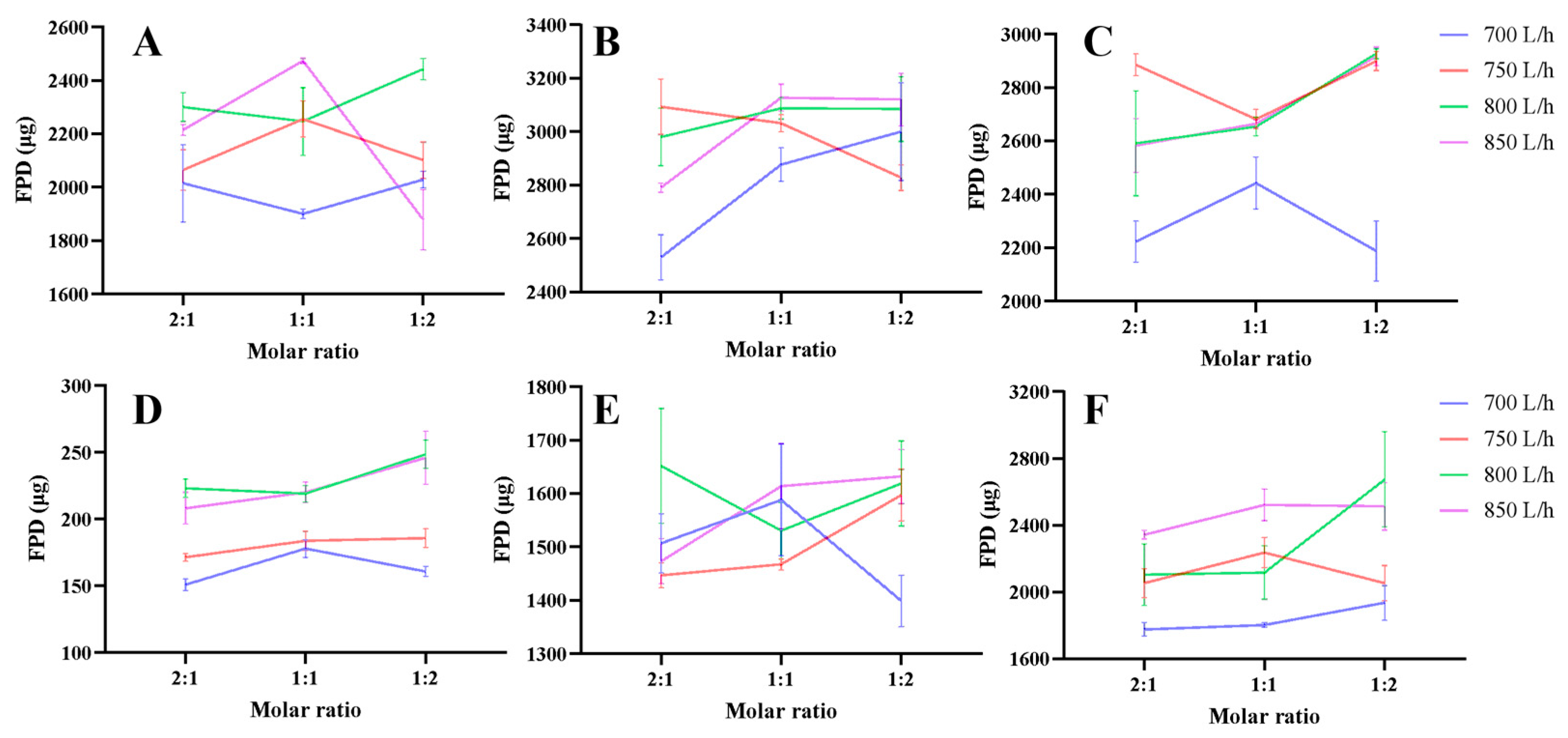

3.1. Aerodynamic Performance

3.2. Characterization of DPIs

3.3. Model Performance

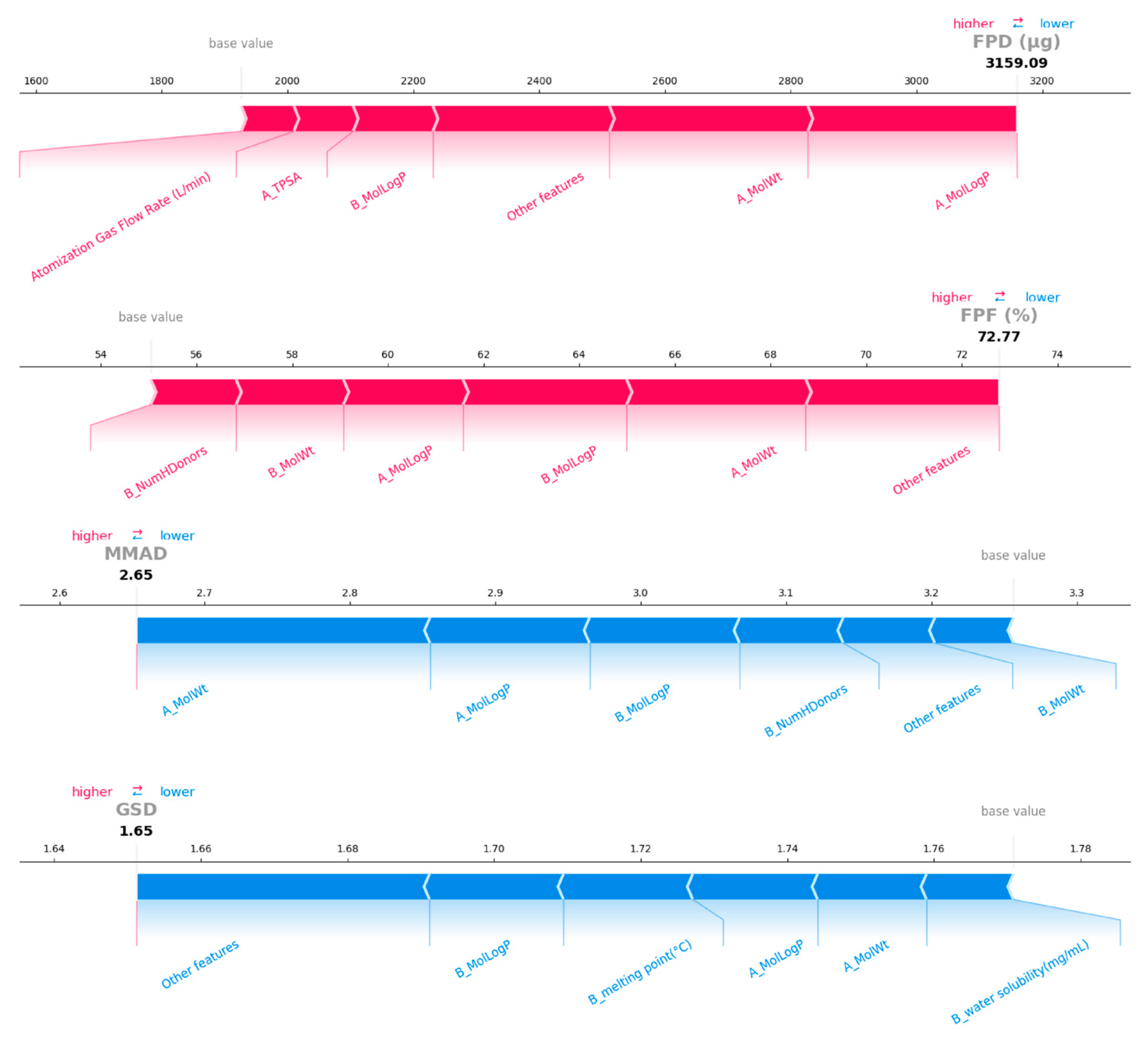

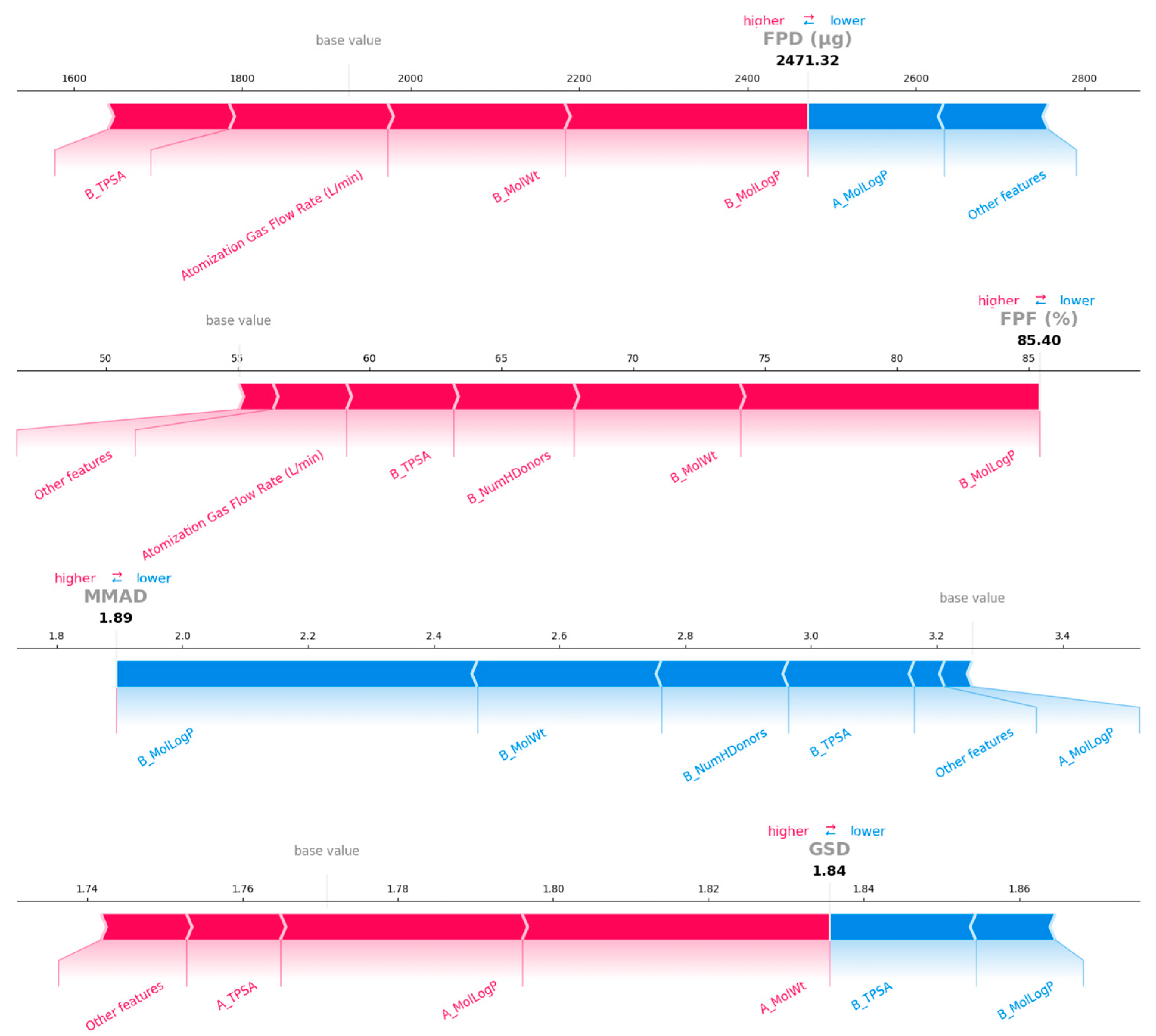

3.4. Model Interpretation

4. Discussion

4.1. Inhalable Property of Spray-Dried DPIs

4.2. Model Development and Selection

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trajman, A.; Campbell, J.R.; Kunor, T.; Ruslami, R.; Amanullah, F.; Behr, M.A.; Menzies, D. Tuberculosis. Lancet 2025, 405, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis: Module 4: Treatment and Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240107243 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/6833f3e7-4721-4ddc-b211-648e95f0de93/content (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis: Module 1: Prevention—Infection Prevention and Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240055889 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Chae, J.; Choi, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Choi, J. Inhalable nanoparticles delivery targeting alveolar macrophages for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2021, 132, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drugbank. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/drugs (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Rifampin for Injection. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2025/050420s093,050627s038lbl.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Rifampin Capsules. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/050429s087lbl.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Rifampin, Isoniazid and Pyrazinamide Tablets. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2025/050705s028lbl.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Conte, J.E.; Golden, J.A.; McQuitty, M.; Kipps, J.; Duncan, S.; McKenna, E.; Zurlinden, E. Effects of Gender, AIDS, and Acetylator Status on Intrapulmonary Concentrations of Isoniazid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2358–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, E.; Sharafeldin, N.; Reinisch, V.; Mohsenzada, N.; Mitsche, S.; Schröttner, H.; Zellnitz-Neugebauer, S. Development of Co-Amorphous Systems for Inhalation Therapy—Part 2: In Silico Guided Co-Amorphous Rifampicin–Moxifloxacin and –Ethambutol Formulations. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotz, E.; Tateosian, N.L.; Salgueiro, J.; Bernabeu, E.; Gonzalez, L.; Manca, M.L.; Amiano, N.; Valenti, D.; Manconi, M.; García, V.; et al. Pulmonary delivery of rifampicin-loaded soluplus micelles against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 101170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Vaghasiya, K.; Gupta, P.; Singh, A.K.; Gupta, U.D.; Verma, R.K. Dynamic mucus penetrating microspheres for efficient pulmonary delivery and enhanced efficacy of host defence peptide (HDP) in experimental tuberculosis. J. Control. Release 2020, 324, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajj, N.; O’Reilly, N.J.; Cathcart, H. Leucine as an excipient in spray dried powder for inhalation. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 2384–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, N.; Cipolla, D.; Park, H.; Zhou, Q.T. Physical stability of dry powder inhaler formulations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardenhire, D.S.; Nozart, L.; Hinski, S.T. Dry-Powder Inhalers. In A Guide to Aerosol Delivery Devices for Respiratory Therapists, 5th ed.; Vries, M.D., Ed.; American Association for Respiratory Care: Irving, TX, USA, 2023; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Alhajj, N.; O’Reilly, N.J.; Cathcart, H. Designing enhanced spray dried particles for inhalation: A review of the impact of excipients and processing parameters on particle properties. Powder Technol. 2021, 384, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Pan, X.; Wu, C.; Jiang, J. Recent advances in dry powder inhalation formulations prepared by co-spray drying technology: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 681, 125825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, W.-R.; Chang, R.Y.K.; Chan, H.-K. Engineering the right formulation for enhanced drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 191, 114561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbagh, A.; Abu Kasim, N.H.; Yeong, C.H.; Wong, T.W.; Abdul Rahman, N. Critical Parameters for Particle-Based Pulmonary Delivery of Chemotherapeutics. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2018, 31, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.P.; Clarke, S.W. Therapeutic aerosols 1--physical and practical considerations. Thorax 1983, 38, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, A.H.L.; Tong, H.H.Y.; Chattopadhyay, P.; Shekunov, B.Y. Particle Engineering for Pulmonary Drug Delivery. Pharm. Res. 2007, 24, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, T.; López-Iglesias, C.; Szewczyk, P.K.; Stachewicz, U.; Barros, J.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Alnaief, M.; García-González, C.A. A Pathway From Porous Particle Technology Toward Tailoring Aerogels for Pulmonary Drug Administration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 671381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehring, R. Pharmaceutical Particle Engineering via Spray Drying. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 999–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsapis, N.; Bennett, D.; Jackson, B.; Weitz, D.A.; Edwards, D.A. Trojan particles: Large porous carriers of nanoparticles for drug delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 12001–12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.R.; Bērziņš, K.; Fraser-Miller, S.J.; Gordon, K.C.; Das, S.C. Co-Amorphization of Kanamycin with Amino Acids Improves Aerosolization. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.R.; Sinha, S.; Gordon, K.C.; Das, S.C. Amino acids improve aerosolization and chemical stability of potential inhalable amorphous Spray-dried ceftazidime for Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 621, 121799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, G.; Cai, S.; Jing, H.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; et al. Moisture-Resistant Co-Spray-Dried Netilmicin with l-Leucine as Dry Powder Inhalation for the Treatment of Respiratory Infections. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübl, A.; Most, J.; Hauß, C.; Planz, V.; Windbergs, M. Development of spray-dried phage-aztreonam microparticles for inhalation therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2026, 219, 114966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Party, P.; Soliman, L.; Nagy, A.; Farkas, Á.; Ambrus, R. Optimization, In Vitro, and In Silico Characterization of Theophylline Inhalable Powder Using Raffinose-Amino Acid Combination as Fine Co-Spray-Dried Carriers. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Rades, T.; Rantanen, J.; Yang, M. Inhalable co-amorphous budesonide-arginine dry powders prepared by spray drying. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 565, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabelmann, A.; Lehr, C.-M.; Grohganz, H. Preparation of Co-Amorphous Levofloxacin Systems for Pulmonary Application. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoubadi, M.; Gregson, F.K.A.; Wang, H.; Carrigy, N.B.; Nicholas, M.; Gracin, S.; Lechuga-Ballesteros, D.; Reid, J.P.; Finlay, W.H.; Vehring, R. Trileucine as a dispersibility enhancer of spray-dried inhalable microparticles. J. Control. Release 2021, 336, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.; McCollum, J.; Wang, H.; Ordoubadi, M.; Jar, C.; Carrigy, N.B.; Barona, D.; Tetreau, I.; Archer, M.; Gerhardt, A.; et al. Development of a formulation platform for a spray-dried, inhalable tuberculosis vaccine candidate. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 593, 120121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ye, Z.; Gao, H.; Ouyang, D. Computational pharmaceutics-A new paradigm of drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2021, 338, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vora, L.K.; Gholap, A.D.; Jetha, K.; Thakur, R.R.; Solanki, H.K.; Chavda, V.P. Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutical Technology and Drug Delivery Design. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Bufton, J.; Hickman, R.J.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Bannigan, P.; Allen, C. Revolutionizing drug formulation development: The increasing impact of machine learning. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 202, 115108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannigan, P.; Aldeghi, M.; Bao, Z.; Häse, F.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Allen, C. Machine learning directed drug formulation development. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 175, 113806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Peng, H.-H.; Yang, Z.; Ma, X.; Sahakijpijarn, S.; Moon, C.; Ouyang, D.; Williams, R.O., III. The applications of Machine learning (ML) in designing dry powder for inhalation by using thin-film-freezing technology. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 626, 122179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J.M.; Baumann, J.M.; Morgen, M.M. Predicting spray dried dispersion particle size via machine learning regression methods. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 3223–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pubchem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Kumar, C.S.; Choudary, M.N.S.; Bommineni, V.B.; Tarun, G.; Anjali, T. Dimensionality Reduction based on SHAP Analysis: A Simple and Trustworthy Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), Chennai, India, 28–30 July 2020; pp. 558–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherukuvada, S.; Thakuria, R.; Nangia, A. Pyrazinamide Polymorphs: Relative Stability and Vibrational Spectroscopy. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 3931–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehring, R.; Foss, W.R.; Lechuga-Ballesteros, D. Particle formation in spray drying. J. Aerosol Sci. 2007, 38, 728–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Features |

|---|---|

| Drug | MolWt, MolLogP, TPSA, NumHDonors, NumHAcceptors, melting point (°C), water solubility (mg/mL) |

| Amino acid | MolWt, MolLogP, TPSA, NumHDonors, NumHAcceptors, melting point (°C), water solubility (mg/mL) |

| Conditions | Molar ratio, Atomization Gas Flow Rate (L/min) |

| Target variables | FPD (μg), FPF (%), MMAD (µm), GSD |

| ML Algorithms | Hyperparameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | n_estimators | max_depth | min_samples_leaf | min_samples_split | max_samples | |

| 150 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 0.9 | ||

| XGBoost | learning_rate | n_estimators | max_depth | subsample | colsample_bytree | min_child_weight |

| 0.2 | 100 | 3 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| SVM | Kernel function | C | gamma | |||

| rbf | 1 | auto | ||||

| MLP | hidden_layer_sizes | activation | optimizer | learning_rate | ||

| (20, 10) | tanh | SGD | 0.1 | |||

| ML Algorithms | RF | XGB | SVM | MLP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Test | CV | Train | Test | CV | Train | Test | CV | Train | Test | CV | |

| FPD_R2 | 0.974 | 0.961 | 0.937 | 0.997 | 0.964 | 0.928 | 0.980 | 0.965 | 0.945 | 0.975 | 0.967 | 0.943 |

| FPD_MAE | 111.594 | 128.873 | 185.426 | 39.643 | 133.893 | 189.717 | 104.331 | 129.216 | 169.274 | 108.597 | 121.438 | 160.303 |

| FPD_RMSE | 149.713 | 171.962 | 229.030 | 54.636 | 163.984 | 245.182 | 131.444 | 161.969 | 210.994 | 146.954 | 158.204 | 213.571 |

| FPF_R2 | 0.988 | 0.966 | 0.963 | 0.999 | 0.991 | 0.980 | 0.988 | 0.950 | 0.973 | 0.989 | 0.968 | 0.969 |

| FPF_MAE | 1.993 | 2.692 | 3.876 | 0.624 | 1.547 | 2.612 | 2.243 | 3.360 | 3.222 | 1.871 | 2.620 | 2.755 |

| FPF_RMSE | 2.743 | 3.898 | 4.557 | 0.798 | 1.997 | 3.492 | 2.770 | 4.678 | 4.064 | 2.626 | 3.737 | 4.124 |

| MMAD_R2 | 0.984 | 0.966 | 0.952 | 0.996 | 0.982 | 0.922 | 0.978 | 0.939 | 0.934 | 0.982 | 0.976 | 0.963 |

| MMAD_MAE | 0.083 | 0.107 | 0.171 | 0.040 | 0.105 | 0.196 | 0.125 | 0.184 | 0.193 | 0.112 | 0.117 | 0.156 |

| MMAD_RMSE | 0.164 | 0.212 | 0.268 | 0.080 | 0.154 | 0.345 | 0.192 | 0.284 | 0.306 | 0.174 | 0.178 | 0.217 |

| GSD_R2 | 0.964 | 0.898 | 0.910 | 0.997 | 0.894 | 0.893 | 0.967 | 0.881 | 0.904 | 0.961 | 0.903 | 0.890 |

| GSD_MAE | 0.022 | 0.041 | 0.034 | 0.007 | 0.038 | 0.037 | 0.020 | 0.041 | 0.036 | 0.022 | 0.040 | 0.035 |

| GSD_RMSE | 0.029 | 0.048 | 0.042 | 0.009 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.028 | 0.052 | 0.046 | 0.030 | 0.047 | 0.049 |

| Formulation | Atomizer (L/h) | Ratio of Drug to Amino Acid | FPD (µg) | Predicted FPD | FPF (%) | Predicted FPF | MMAD (µm) | Predicted MMAD | GSD | Predicted GSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIF-LLA | 850 | 1:1 | 3127.32 | 3159.09 | 73.08 | 72.77 | 2.63 | 2.65 | 1.65 | 1.65 |

| PYR-LL | 850 | 1:1 | 2521.71 | 2471.32 | 86.31 | 85.40 | 1.88 | 1.89 | 1.84 | 1.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, A.; Pan, X.; Wu, C.; Jiang, J. Machine Learning-Guided Development of Anti-Tuberculosis Dry Powder for Inhalation Prepared by Co-Spray Drying. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020191

Hu X, Chen X, Zhou Z, Wang A, Pan X, Wu C, Jiang J. Machine Learning-Guided Development of Anti-Tuberculosis Dry Powder for Inhalation Prepared by Co-Spray Drying. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(2):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020191

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Xiaoyun, Xian Chen, Ziling Zhou, Aichao Wang, Xin Pan, Chuanbin Wu, and Junhuang Jiang. 2026. "Machine Learning-Guided Development of Anti-Tuberculosis Dry Powder for Inhalation Prepared by Co-Spray Drying" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 2: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020191

APA StyleHu, X., Chen, X., Zhou, Z., Wang, A., Pan, X., Wu, C., & Jiang, J. (2026). Machine Learning-Guided Development of Anti-Tuberculosis Dry Powder for Inhalation Prepared by Co-Spray Drying. Pharmaceutics, 18(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020191