Combined Intraperitoneal and Systemic Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Metastases: Drug Delivery Concepts, Pharmacokinetics, and Clinical Applications: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

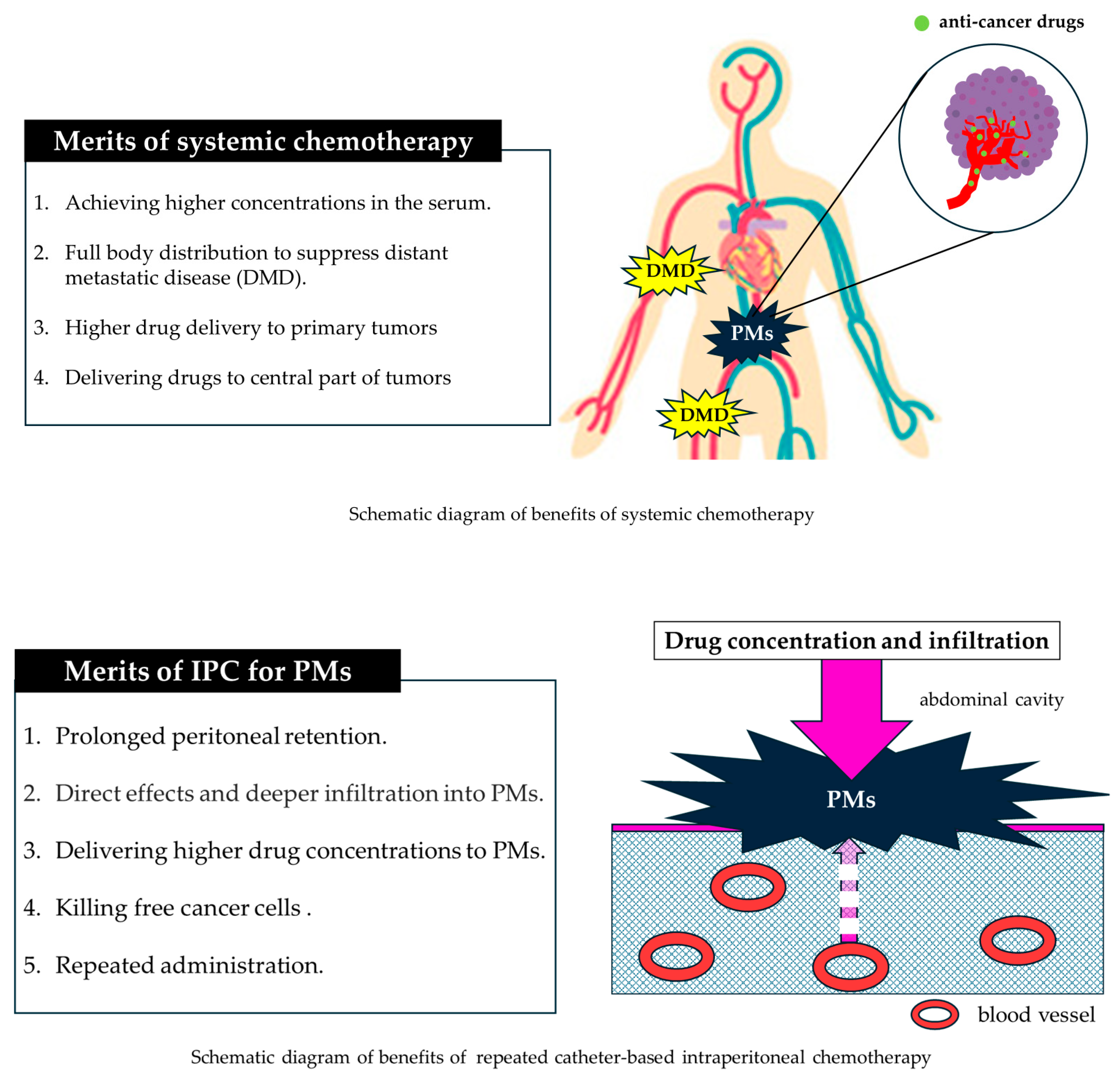

3. Benefits of the Intraperitoneal Approach

4. Disadvantages of the Intraperitoneal Approach

5. Combination with Systemic Chemotherapy

6. Clinical Trials of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy by Cancer Type

6.1. Ovarian Cancer

6.2. Pancreatic Cancer

6.3. Gastric Cancer

6.4. Colorectal Cancer

6.5. Pseudomyxoma Peritonei

6.6. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

7. Future Directions

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMs | Peritoneal metastases |

| IPC | Intraperitoneal chemotherapy |

| IP | Intraperitoneal |

| IV | Intravenous |

| iPocc | Intraperitoneal Therapy for Ovarian Cancer with Carboplatin |

| HIPEC | Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy |

| PIPAC | Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| CRS | Cytoreductive surgery |

| GC | Gastric cancer |

| OS | Overall survival |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| PDS | Primary debulking surgery |

| CDDP | Cisplatin |

| CPA | Cyclophosphamide |

| PTX | Paclitaxel |

| CBDCA | Carboplatin |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| PFS | Progression free survival |

| MA | Malignant ascites |

| FOLFORINOX | Fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin |

| GEM | Gemcitabine |

| FN | Febrile neutropenia |

| MMC | Mitomycin C |

| NRCT | Nonrandomized control trials |

| RR | Risk ratio |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| Bev | Bevacizumab |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PMP | Pseudomyxoma peritonei |

| EPIC | Early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| L-OHP | Oxaliplatin |

| Doxo | Doxorubicin |

| CPT-11 | Irinotecan |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

References

- Ishigami, H.; Fujiwara, Y.; Fukushima, R.; Nashimoto, A.; Yabusaki, H.; Imano, M.; Imamoto, H.; Kodera, Y.; Uenosono, Y.; Amagai, K.; et al. Phase III trial comparing intraperitoneal and intravenous paclitaxel plus S-1 versus cisplatin plus S-1 in patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis: PHOENIX-GC trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1922–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Tanabe, H.; Okamoto, A.; Takehara, K.; Saito, M.; Fujiwara, H.; Tan, D.S.P.; Yamaguchi, S.; et al. Intraperitoneal Carboplatin for Ovarian Cancer—A Phase 2/3 Trial. NEJM Evid. 2023, 2, EVIDoa2200225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwaal, V.J.; van Ruth, S.; de Bree, E.; van Sloothen, G.W.; van Tinteren, H.; Boot, H.; Zoetmulder, F.A. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3737–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Fujii, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Takami, H.; Yoshioka, I.; Yamaki, S.; Sonohara, F.; Shibuya, K.; Motoi, F.; Hirano, S.; et al. Phase I/II study of adding intraperitoneal paclitaxel in patients with pancreatic cancer and peritoneal metastasis. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 1811–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, B.; Lang, H.; Koenigsrainer, A.; Gockel, I.; Rau, H.G.; Seeliger, H.; Lerchenmueller, C.; Reim, D.; Wahba, R.; Angele, M.; et al. Effect of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy on Cytoreductive Surgery in Gastric Cancer with Synchronous Peritoneal Metastases: The Phase III GASTRIPEC-I Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Driel, W.J.; Koole, S.N.; Sikorska, K.; Schagen van Leeuwen, J.H.; Schreuder, H.W.R.; Hermans, R.H.M.; de Hingh, I.H.J.T.; van der Velden, J.; Arts, H.J.; Massuger, L.F.A.G.; et al. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommariva, A.; Tonello, M.; Coccolini, F.; De Manzoni, G.; Delrio, P.; Pizzolato, E.; Gelmini, R.; Serra, F.; Rreka, E.; Pasqual, E.M.; et al. Colorectal Cancer with Peritoneal Metastases: The Impact of the Results of PROPHYLOCHIP, COLOPEC, and PRODIGE 7 Trials on Peritoneal Disease Management. Cancers 2022, 15, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanenburg, E.S.; El Klaver, C.; Wisselink, D.D.; Punt, C.J.A.; Snaebjornsson, P.; Crezee, J.; Aalbers, A.G.J.; Brandt-Kerkhof, A.R.M.; Bremers, A.J.A.; Burger, P.J.W.A.; et al. Adjuvant Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Colon Cancer (COLOPEC): 5-Year Results of a Randomized Multicenter Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagotti, A.; Costantini, B.; Fanfani, F.; Giannarelli, D.; De Iaco, P.; Chiantera, V.; Mandato, V.; Giorda, G.; Aletti, G.; Greggi, S.; et al. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Platinum-Sensitive Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: A Randomized Trial on Survival Evaluation (HORSE; MITO-18). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perelló-Trias, M.T.; Serrano-Muñoz, A.J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Segura-Sampedro, J.J.; Ramis, J.M.; Monjo, M. Intraperitoneal drug delivery systems for peritoneal carcinomatosis: Bridging the gap between research and clinical implementation. J. Control Release 2024, 373, 70–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, P.C.S.; Guchelaar, N.A.D.; Sassen, S.D.T.; Koch, B.C.P.; Mathijssen, R.H.J.; Koolen, S.L.W. A Clinical Pharmacological Perspective on Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. Drugs 2025, 85, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Kitayama, J.; Nagai, R.; Aizawa, K. Anatomical Targeting of Anticancer Drugs to Solid Tumors Using Specific Administration Routes: Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchelaar, N.A.D.; Noordman, B.J.; Koolen, S.L.W.; Mostert, B.; Madsen, E.V.E.; Burger, J.W.A.; Brandt-Kerkhof, A.R.M.; Creemers, G.J.; de Hingh, I.H.J.T.; Luyer, M.; et al. Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Unresectable Peritoneal Surface Malignancies. Drugs 2023, 83, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.H.; Peng, K.W.; Li, Y. Intraperitoneal free cancer cells in gastric cancer: Pathology of peritoneal carcinomatosis and rationale for intraperitoneal chemotherapy/hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in gastric cancer. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 1, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, M.D.; McPartland, S.; Detelich, D.; Saif, M.W. Chemotherapy for intraperitoneal use: A review of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy and early post-operative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2016, 7, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bree, E.; Michelakis, D.; Stamatiou, D.; Romanos, J.; Zoras, O. Pharmacological principles of intraperitoneal and bidirectional chemotherapy. Pleura Peritoneum 2017, 2, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugarbaker, P.H. Intraperitoneal paclitaxel: Pharmacology, clinical results and future prospects. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 12, S231–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, D.; Kitayama, J.; Ishigami, H.; Kaisaki, S.; Nagawa, H. Different tissue distribution of paclitaxel with intravenous and intraperitoneal administration. J. Surg. Res. 2009, 155, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarbaker, P.H.; Van der Speeten, K. Surgical technology and pharmacology of hyperthermic perioperative chemotherapy. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2016, 7, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, D.S.; Young, L.; Mason, N.; Salmon, S.E. In vitro evaluation of anticancer drugs against ovarian cancer at concentrations achievable by intraperitoneal administration. Semin. Oncol. 1985, 12, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, P.Q.; Han, I.H.; Seow, K.M.; Chen, K.H. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC): An Overview of the Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Actions and Effects on Epithelial Ovarian Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, B.; Brandl, A.; Piso, P.; Pelz, J.; Busch, P.; Demtröder, C.; Schüle, S.; Schlitt, H.J.; Roitman, M.; Tepel, J.; et al. Peritoneal metastasis in gastric cancer: Results from the German database. Gastric Cancer 2020, 23, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnot, P.E.; Piessen, G.; Kepenekian, V.; Decullier, E.; Pocard, M.; Meunier, B.; Bereder, J.M.; Abboud, K.; Marchal, F.; Quenet, F.; et al. Cytoreductive Surgery with or Without Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Gastric Cancer with Peritoneal Metastases (CYTO-CHIP study): A Propensity Score Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2028–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, R.A.; O’Cearbhaill, R.E.; Zivanovic, O.; Chi, D.S. Current status and future prospects of hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) clinical trials in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Hyperth. 2017, 33, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franko, J.; Ibrahim, Z.; Gusani, N.J.; Holtzman, M.P.; Bartlett, D.L.; Zeh, H.J., 3rd. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion versus systemic chemotherapy alone for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer 2010, 116, 3756–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirnezami, R.; Mehta, A.M.; Chandrakumaran, K.; Cecil, T.; Moran, B.J.; Carr, N.; Verwaal, V.J.; Mohamed, F.; Mirnezami, A.H. Cytoreductive surgery in combination with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival in patients with colorectal peritoneal metastases compared with systemic chemotherapy alone. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, T.C.; Moran, B.J.; Sugarbaker, P.H.; Levine, E.A.; Glehen, O.; Gilly, F.N.; Baratti, D.; Deraco, M.; Elias, D.; Sardi, A.; et al. Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2449–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.; Chandrakumaran, K.; Dayal, S.; Mohamed, F.; Cecil, T.D.; Moran, B.J. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in 1000 patients with perforated appendiceal epithelial tumours. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 42, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.J.; Carbajal, J.; Alfaro, A.L.; Saravia, L.G.; Zanabria, D.; Araujo, J.M.; Quispe, L.; Zevallos, A.; Buleje, J.L.; Cho, C.E.; et al. Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2023, 181, 103841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonemura, Y.; Kawamura, T.; Bandou, E.; Takahashi, S.; Sawa, T.; Matsuki, N. Treatment of peritoneal dissemination from gastric cancer by peritonectomy and chemohyperthermic peritoneal perfusion. Br. J. Surg. 2005, 92, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; Shrestha, R.D.; Kokubun, M.; Ohta, M.; Takahashi, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Kiuchi, S.; Okui, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Arimizu, N.; et al. Intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion combined with surgery effective for gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding. Ann. Surg. 1988, 208, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solass, W.; Kerb, R.; Mürdter, T.; Giger-Pabst, U.; Strumberg, D.; Tempfer, C.; Zieren, J.; Schwab, M.; Reymond, M.A. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy of peritoneal carcinomatosis using pressurized aerosol as an alternative to liquid solution: First evidence for efficacy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, M.; Hübner, M.; Grass, F.; Bakrin, N.; Villeneuve, L.; Laplace, N.; Passot, G.; Glehen, O.; Kepenekian, V. Pressurised intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy: Rationale, evidence, and potential indications. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e368–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giorgio, A.; Sgarbura, O.; Rotolo, S.; Schena, C.A.; Bagalà, C.; Inzani, F.; Russo, A.; Chiantera, V.; Pacelli, F. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy with cisplatin and doxorubicin or oxaliplatin for peritoneal metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920940887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Tan, H.L.; Sundar, R.; Lieske, B.; Chee, C.E.; Ho, J.; Shabbir, A.; Babak, M.V.; Ang, W.H.; Goh, B.C.; et al. PIPAC-OX: A Phase I Study of Oxaliplatin-Based Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy in Patients with Peritoneal Metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robella, M.; De Simone, M.; Berchialla, P.; Argenziano, M.; Borsano, A.; Ansari, S.; Abollino, O.; Ficiarà, E.; Cinquegrana, A.; Cavalli, R.; et al. A Phase I Dose Escalation Study of Oxaliplatin, Cisplatin and Doxorubicin Applied as PIPAC in Patients with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Cancers 2021, 13, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceelen, W.; Sandra, L.; de Sande, L.V.; Graversen, M.; Mortensen, M.B.; Vermeulen, A.; Gasthuys, E.; Reynders, D.; Cosyns, S.; Hoorens, A.; et al. Phase I study of intraperitoneal aerosolized nanoparticle albumin based paclitaxel (NAB-PTX) for unresectable peritoneal metastases. EBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyami, M.; Bonnot, P.E.; Mercier, F.; Laplace, N.; Villeneuve, L.; Passot, G.; Bakrin, N.; Kepenekian, V.; Glehen, O. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) for unresectable peritoneal metastasis from gastric cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosrawipour, T.; Khosrawipour, V.; Giger-Pabst, U. Pressurized Intra Peritoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy in patients suffering from peritoneal carcinomatosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, F.; Struller, F.; Horvath, P.; Solass, W.; Bösmüller, H.; Königsrainer, A.; Reymond, M.A. Feasibility, Safety, and Efficacy of Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) for Peritoneal Metastasis: A Registry Study. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 2743985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyami, M.; Gagniere, J.; Sgarbura, O.; Cabelguenne, D.; Villeneuve, L.; Pezet, D.; Quenet, F.; Glehen, O.; Bakrin, N.; Passot, G. Multicentric initial experience with the use of the pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) in the management of unresectable peritoneal carcinomatosis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 43, 2178–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver Goetze, T.; Al-Batran, S.E.; Pabst, U.; Reymond, M.; Tempfer, C.; Bechstein, W.O.; Bankstahl, U.; Gockel, I.; Königsrainer, A.; Kraus, T.; et al. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) in combination with standard of care chemotherapy in primarily untreated chemo naïve upper gi-adenocarcinomas with peritoneal seeding—A phase II/III trial of the AIO/CAOGI/ACO. Pleura Peritoneum 2018, 3, 20180113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakrin, N.; Tempfer, C.; Scambia, G.; De Simone, M.; Gabriel, B.; Grischke, E.M.; Rau, B. PIPAC-OV3: A multicenter, open-label, randomized, two-arm phase III trial of the effect on progression-free survival of cisplatin and doxorubicin as Pressurized Intra-Peritoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) vs. chemotherapy alone in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer. Pleura Peritoneum 2018, 3, 20180114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, P.B.; Stahl, C.C.; Vande Walle, K.A.; Pokrzywa, C.J.; Cherney Stafford, L.M.; Aiken, T.; Barrett, J.; Acher, A.W.; Leverson, G.; Ronnekleiv-Kelly, S.; et al. What Drives High Costs of Cytoreductive Surgery and HIPEC: Patient, Provider or Tumor? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 4920–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, L.; Zhang, W.; Ni, L.; Xu, Z.; Yang, K.; Gou, H.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, M.; Yang, Y.; Hu, J.; et al. Study of SOX combined with intraperitoneal high-dose paclitaxel in gastric cancer with synchronous peritoneal metastasis: A phase II single-arm clinical trial. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 4161–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, Y.; Lan, D.; Bao, W.; Yang, H.; Zhou, S.; Huang, F.; Wang, M.; Peng, Z. SOX combined with intraperitoneal perfusion of docetaxel compared with DOS regimen in the first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer with malignant ascites: A prospective observation. Trials 2022, 23, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, D.K.A.; Sundar, R.; Kim, G.; Ang, J.J.; Lum, J.H.Y.; Nga, M.E.; Goh, G.H.; Seet, J.E.; Chee, C.E.; Tan, H.L.; et al. Outcomes of a Phase II Study of Intraperitoneal Paclitaxel plus Systemic Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin (XELOX) for Gastric Cancer with Peritoneal Metastases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8597–8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ohzawa, H.; Miyato, H.; Kanamaru, R.; Kurashina, K.; Hosoya, Y.; Lefor, A.K.; Sata, N.; Kitayama, J. Intraperitoneal Administration of Paclitaxel Combined with S-1 Plus Oxaliplatin as Induction Therapy for Patients with Advanced Gastric Cancer with Peritoneal Metastases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 3863–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.A.; Krikorian, J.G.; Reich, S.D.; Smyth, R.D.; Lee, F.H.; Issell, B.F. Clinical pharmacology of intraperitoneal cisplatin. Gynecol. Oncol. 1985, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Kurashina, K.; Saito, S.; Kanamaru, R.; Ohzawa, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Miyato, H.; Hosoya, Y.; Lefor, A.K.; Sata, N.; et al. Flow cytometry-based analysis of tumor-leukocyte ratios in peritoneal fluid from patients with advanced gastric cancer. Cytom. B Clin. Cytom. 2021, 100, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Kurashina, K.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kanamaru, R.; Ohzawa, H.; Miyato, H.; Saito, S.; Hosoya, Y.; Lefor, A.K.; Sata, N.; et al. Altered intraperitoneal immune microenvironment in patients with peritoneal metastases from gastric cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 969468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Mu, W.; Liao, C.G.; Hou, Y.; Song, J.; Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of cisplatin in the systemic versus hyperthermic intrathoracic or intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2024, 95, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, F.; Gong, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Shen, L. Phase I study of intraperitoneal bevacizumab for treating refractory malignant ascites. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 300060520986664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideris, M.; Menon, U.; Manchanda, R. Screening and prevention of ovarian cancer. Med. J. Aust. 2024, 220, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannistra, S.A. Cancer of the ovary. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2519–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Gore, M. Recent advances in systemic treatments for ovarian cancer. Cancer Imaging 2012, 12, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, D.S.; Liu, P.Y.; Hannigan, E.V.; O’Toole, R.; Williams, S.D.; Young, J.A.; Franklin, E.W.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L.; Malviya, V.K.; DuBeshter, B. Intraperitoneal cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide versus intravenous cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide for stage III ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 1950–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markman, M.; Bundy, B.N.; Alberts, D.S.; Fowler, J.M.; Clark-Pearson, D.L.; Carson, L.F.; Wadler, S.; Sickel, J. Phase III trial of standard-dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high-dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small-volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: An intergroup study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.K.; Bundy, B.; Wenzel, L.; Huang, H.Q.; Baergen, R.; Lele, S.; Copeland, L.J.; Walker, J.L.; Burger, R.A.; Gynecologic Oncology Group. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabasag, C.J.; Ferlay, J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Weber, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Pancreatic cancer: An increasing global public health concern. Gut 2022, 71, 1686–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, A.; Kelly, P.; Turkington, R.C.; Jones, C.; Coleman, H.G.; McCain, R.S. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4846–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, N.E.; Prendergast, C.; Lowy, A.M. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: Definitions and management. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 10740–10751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sener, S.F.; Fremgen, A.; Menck, H.R.; Winchester, D.P. Pancreatic cancer: A report of treatment and survival trends for 100,313 patients diagnosed from 1985–1995, using the National Cancer Database. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1999, 189, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomassen, I.; Lemmens, V.E.; Nienhuijs, S.W.; Luyer, M.D.; Klaver, Y.L.; de Hingh, I.H. Incidence, prognosis, and possible treatment strategies of peritoneal carcinomatosis of pancreatic origin: A population-based study. Pancreas 2013, 42, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, T.M.; van Erning, F.N.; van der Geest, L.G.M.; de Groot, J.W.B.; Haj Mohammad, N.; Lemmens, V.E.; van Laarhoven, H.W.; Besselink, M.G.; Wilmink, J.W.; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Association between primary origin (head, body and tail) of metastasised pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and oncologic outcome: A population-based analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 106, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahara, N.; Isayama, H.; Nakai, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Saito, K.; Hamada, T.; Mizuno, S.; Miyabayashi, K.; Mohri, D.; Kogure, H.; et al. Pancreatic cancer with malignant ascites: Clinical features and outcomes. Pancreas 2015, 44, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrone, C.R.; Haas, B.; Tang, L.; Coit, D.G.; Fong, Y.; Brennan, M.F.; Allen, P.J. The influence of positive peritoneal cytology on survival in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2006, 10, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T.; Desseigne, F.; Ychou, M.; Bouché, O.; Guimbaud, R.; Bécouarn, Y.; Adenis, A.; Raoul, J.L.; Gourgou-Bourgade, S.; de la Fouchardière, C.; et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hoff, D.D.; Ervin, T.; Arena, F.P.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.; Moore, M.; Seay, T.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Ma, W.W.; Saleh, M.N.; et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoi, S.; Fujii, T.; Yanagimoto, H.; Motoi, F.; Kurata, M.; Takahara, N.; Yamada, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Mizuma, M.; Honda, G.; et al. Multicenter Phase II Study of Intravenous and Intraperitoneal Paclitaxel with S-1 for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Patients with Peritoneal Metastasis. Ann. Surg. 2017, 265, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Fujii, T.; Hirano, S.; Motoi, F.; Honda, G.; Uemura, K.; Kitayama, J.; Unno, M.; Kodera, Y.; Yamaue, H.; et al. Randomized phase III trial of intravenous and intraperitoneal paclitaxel with S-1 versus gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with peritoneal metastasis (SP study). Trials 2023, 23, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijken, A.; Lurvink, R.J.; Luyer, M.D.P.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G.A.P.; van Erning, F.N.; van Sandick, J.W.; de Hingh, I.H.J.T. The Burden of Peritoneal Metastases from Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review on the Incidence, Risk Factors and Survival. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koemans, W.J.; Lurvink, R.J.; Grootscholten, C.; Verhoeven, R.H.A.; de Hingh, I.H.; van Sandick, J.W. Synchronous peritoneal metastases of gastric cancer origin: Incidence, treatment and survival of a nationwide Dutch cohort. Gastric Cancer 2021, 24, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Shi, C.; Wu, R.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Q. Peritoneal recurrence in gastric cancer following curative resection can be predicted by postoperative but not preoperative biomarkers: A single-institution study of 320 cases. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 78120–78132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desiderio, J.; Chao, J.; Melstrom, L.; Warner, S.; Tozzi, F.; Fong, Y.; Parisi, A.; Woo, Y. The 30-year experience-A meta-analysis of randomised and high-quality non-randomised studies of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the treatment of gastric cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 79, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granieri, S.; Bonomi, A.; Frassini, S.; Chierici, A.P.; Bruno, F.; Paleino, S.; Kusamura, S.; Germini, A.; Facciorusso, A.; Deraco, M.; et al. Prognostic impact of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in gastric cancer patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 2757–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.F.; Lv, L.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, C.G. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) Combined with Surgery: A 12-Year Meta-Analysis of this Promising Treatment Strategy for Advanced Gastric Cancer at Different Stages. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3170–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.J.; Huang, C.Q.; Suo, T.; Mei, L.J.; Yang, G.L.; Cheng, F.L.; Zhou, Y.F.; Xiong, B.; Yonemura, Y.; Li, Y. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: Final results of a phase III randomized clinical trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 1575–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, H.; Kitayama, J.; Kaisaki, S.; Hidemura, A.; Kato, M.; Otani, K.; Kamei, T.; Soma, D.; Miyato, H.; Yamashita, H.; et al. Phase II study of weekly intravenous and intraperitoneal paclitaxel combined with S-1 for advanced gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Kitayama, J.; Ishigami, H.; Emoto, S.; Yamashita, H.; Watanabe, T. A phase 2 trial of intravenous and intraperitoneal paclitaxel combined with S-1 for treatment of gastric cancer with macroscopic peritoneal metastasis. Cancer 2013, 119, 3354–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, D.; Kodera, Y.; Fukushima, R.; Morita, M.; Fushida, S.; Yamashita, N.; Yoshikawa, K.; Ueda, S.; Yabusaki, H.; Kusumoto, T.; et al. Phase II Study of Intraperitoneal Administration of Paclitaxel Combined with S-1 and Cisplatin for Gastric Cancer with Peritoneal Metastasis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, W.J.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, C.M.; Park, J.Y.; Jang, Y.J.; Park, J.M.; Kim, J.W.; Jee, Y.S.; Choi, S.I.; Oh, S.C.; et al. Intraperitoneal paclitaxel with systemic S-1 plus oxaliplatin for advanced or recurrent gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis: A single-arm, multicenter phase II clinical trial. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 51, 109603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil, M.; Dayyani, F. Phase II clinical trial of sequential treatment with systemic chemotherapy and intraperitoneal paclitaxel for gastric and gastroesophageal junction peritoneal carcinomatosis—STOPGAP trial. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Yang, Z.Y.; Yan, C.; Liu, W.T.; Ni, Z.T.; Yao, X.X.; Hua, Z.C.; Feng, R.H.; Zheng, Y.N.; Wang, Z.Q.; et al. A phase III trial of neoadjuvant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy for gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segelman, J.; Granath, F.; Holm, T.; Machado, M.; Mahteme, H.; Martling, A. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors for peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2012, 99, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerscher, A.G.; Chua, T.C.; Gasser, M.; Maeder, U.; Kunzmann, V.; Isbert, C.; Germer, C.T.; Pelz, J.O. Impact of peritoneal carcinomatosis in the disease history of colorectal cancer management: A longitudinal experience of 2406 patients over two decades. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 1432–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razenberg, L.G.; van Gestel, Y.R.; Lemmens, V.E.; de Hingh, I.H.; Creemers, G.J. Bevacizumab in Addition to Palliative Chemotherapy for Patients with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis of Colorectal Origin: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Clin. Color. Cancer 2016, 15, e41–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franko, J.; Shi, Q.; Meyers, J.P.; Maughan, T.S.; Adams, R.A.; Seymour, M.T.; Saltz, L.; Punt, C.J.A.; Koopman, M.; Tournigand, C.; et al. Prognosis of patients with peritoneal metastatic colorectal cancer given systemic therapy: An analysis of individual patient data from prospective randomised trials from the Analysis and Research in Cancers of the Digestive System (ARCAD) database. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, D.; Benizri, E.; Di Pietrantonio, D.; Menegon, P.; Malka, D.; Raynard, B. Comparison of two kinds of intraperitoneal chemotherapy following complete cytoreductive surgery of colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 14, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashin, P.H.; Graf, W.; Nygren, P.; Mahteme, H. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis: Prognosis and treatment of recurrences in a cohort study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 38, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, D.; Gilly, F.; Boutitie, F.; Quenet, F.; Bereder, J.M.; Mansvelt, B.; Lorimier, G.; Dubè, P.; Glehen, O. Peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis treated with surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: Retrospective analysis of 523 patients from a multicentric French study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijpers, A.M.; Mirck, B.; Aalbers, A.G.; Nienhuijs, S.W.; de Hingh, I.H.; Wiezer, M.J.; van Ramshorst, B.; van Ginkel, R.J.; Havenga, K.; Bremers, A.J.; et al. Cytoreduction and HIPEC in the Netherlands: Nationwide long-term outcome following the Dutch protocol. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 20, 4224–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quénet, F.; Elias, D.; Roca, L.; Goéré, D.; Ghouti, L.; Pocard, M.; Facy, O.; Arvieux, C.; Lorimier, G.; Pezet, D.; et al. Cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus cytoreductive surgery alone for colorectal peritoneal metastases (PRODIGE 7): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, M.; Teixeira Farinha, H.; Grass, F.; Wolfer, A.; Mathevet, P.; Hahnloser, D.; Demartines, N. Feasibility and Safety of Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2017, 2017, 6852749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleiman, M.J.; Jelip, A.; Buchs, N.; Toso, C.; Liot, E.; Koessler, T.; Meyer, J.; Meurette, G.; Ris, F. Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Carcinomatosis in Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Cancers 2024, 16, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurvink, R.J.; Rovers, K.P.; Nienhuijs, S.W.; Creemers, G.J.; Burger, J.W.A.; de Hingh, I.H.J. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy with oxaliplatin (PIPAC-OX) in patients with colorectal peritoneal metastases-a systematic review. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 12, S242–S258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murono, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Nozawa, H.; Sasaki, K.; Emoto, S.; Matsuzaki, H.; Kashiwabara, K.; Ishigami, H.; Gohda, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; et al. Intraperitoneal paclitaxel combined with FOLFOX/CAPOX plus bevacizumab for colorectal cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis (the iPac-02 trial): Study protocol of a single arm, multicenter, phase 2 study. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2023, 38, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusamura, S.; Barretta, F.; Yonemura, Y.; Sugarbaker, P.H.; Moran, B.J.; Levine, E.A.; Goere, D.; Baratti, D.; Nizri, E.; Morris, D.L.; et al. The Role of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Pseudomyxoma Peritonei After Cytoreductive Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, e206363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarbaker, P.H.; Chang, D. Results of treatment of 385 patients with peritoneal surface spread of appendiceal malignancy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 1999, 6, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Alzahrani, N.A.; Liauw, W.; Traiki, T.B.; Morris, D.L. Early Postoperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Low-Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms with Pseudomyxoma Peritonei: Is it Beneficial? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, A.; Brandl, A.; Wakama, S.; Sako, S.; Ishibashi, H.; Mizumoto, A.; Takao, N.; Noguchi, K.; Motoi, S.; Ichinose, M.; et al. Neoadjuvant Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Patients with Pseudomyxoma Peritonei-A Novel Treatment Approach. Cancers 2020, 12, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Schwarz, L.; Spiliotis, J.; Hsieh, M.C.; Akaishi, E.H.; Goere, D.; Sugarbaker, P.H.; Baratti, D.; Quenet, F.; Bartlett, D.L.; et al. Is there an oncological interest in the combination of CRS/HIPEC for peritoneal carcinomatosis of HCC? Results of a multicenter international study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 1786–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Zhang, K.; Yan, L.; Zhang, Y. Long-term survival outcomes following cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 22, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lin, J.; Gao, K.; Dang, X.; Hua, Y. The Prophylactic Role of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy on Spontaneously Ruptured Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Radical Resection: A Retrospective Study. Cancer Manag. Res. 2025, 17, 3241–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatelle, R.C.; Liu, R.; Hung, Y.P.; Bressler, E.; Neal, E.J.; Martin, A.; Ekladious, I.; Grinstaff, M.W.; Colson, Y.L. Ultra-high drug loading improves nanoparticle efficacy against peritoneal mesothelioma. Biomaterials 2022, 285, 121534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Kimura, N.; Ohzawa, H.; Miyato, H.; Sata, N.; Koyanagi, T.; Saga, Y.; Takei, Y.; Fujiwara, H.; Nagai, R.; et al. Optimizing Timing of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy to Enhance Intravenous Carboplatin Concentration. Cancers 2024, 16, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christou, N.; Auger, C.; Battu, S.; Lalloué, F.; Jauberteau-Marchan, M.O.; Hervieu, C.; Verdier, M.; Mathonnet, M. Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Metastases: Technical Innovations, Preclinical and Clinical Advances and Future Perspectives. Biology 2021, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.; Gerakopoulos, V.; Oehler, R. Metastasis-associated fibroblasts in peritoneal surface malignancies. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asem, M.; Young, A.; Oyama, C.; ClaureDeLaZerda, A.; Liu, Y.; Ravosa, M.J.; Gupta, V.; Jewell, A.; Khabele, D.; Stack, M.S. Ascites-induced compression alters the peritoneal microenvironment and promotes metastatic success in ovarian cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M.; Thibault, B.; Delord, J.P.; Couderc, B. Implication of tumor microenvironment in chemoresistance: Tumor-associated stromal cells protect tumor cells from cell death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 9545–9571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.C.; Hsu, Y.T.; Chang, C.L. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy enhances antitumor effects on ovarian cancer through immune-mediated cancer stem cell targeting. Int. J. Hyperth. 2021, 38, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceelen, W.; Ramsay, R.G.; Narasimhan, V.; Heriot, A.G.; De Wever, O. Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment in Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Directly targets PMs and free intraperitoneal cancer cells with high local drug concentrations. | Requires invasive procedures (port-based IPC requires surgical port placement or HIPEC is one-time during major surgery). |

| Prolonged local drug exposure due to limited systemic absorption, leading to reduced systemic toxicity. | Needs specialized equipment and expertise, making it resource-intensive and high-cost. |

| Deeper penetration of chemotherapy into PMs. | High risk of severe side effects as for hematologic or non-hematologic toxicity). |

| Implantation of IP port enable repeatable administration and outpatient treatment. | Risk of port-related complications (infection, catheter blockage, leakage). |

| IPC can convert some patients to surgery. | Limited evidence from large trials and unclear optimal patient selection. |

| HIPEC further enhances drug penetration and tumor cell kill, achieving high local efficacy. | Does not favorably affect disease outside the peritoneal cavity. |

| Tumor Type | Author, Year | Study, Design | Treatment Regimen | Outcomes | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian | Alberts et al. (1996) [57] | Phase III RCT | IV CDDP 100 mg/m2 + IV CPA 600 mg/m2 vs. IP CDDP 100 mg/m2 + IV CPA 600 mg/m2 | OS: 41 (IV group) vs. 49 months (IP group) (p = 0.02) | IP group has significantly longer OS. |

| Markman et al. (1998) [58] | Phase III RCT | IV PTX 135 mg/m2 + IV CDDP 75 mg/m2 vs. IV CBDCA (AUC9) + IV PTX 135 mg/m2 + IP CDDP 100 mg/m2 | PFS: 22 (IV group) vs. 28 months (IP group) (p = 0.01); OS: 52 (IV group) vs. 63 months (IP group) (p = 0.05) | IPC shows improved PFS and a trend toward OS benefit. | |

| Armstrong et al. (2006) [59] | Phase III RCT | IV PTX 135 mg/m2 + IV CDDP 75 mg/m2 vs. IV PTX 135 mg/m2 + IP CDDP 100 mg/m2 + IP PTX 60 mg/m2 | PFS: 18.3 (IV group) vs. 23.8 months (IP group) (p = 0.05); OS: 49.7 (IV group) vs. 65.6 months (IP group) (p = 0.03) | Markedly better PFS/OS with IP, but <50% completed 6 cycles due to toxicity | |

| Nagao et al. (2020) [2] | Phase II/III RCT | IV PTX 80 mg/m2 (days 1, 8, 15) + IV CBDCA AUC6 vs. IV PTX 80 mg/m2 (days 1, 8, 15) + IP CBDCA AUC6 | PFS: 20.7 (IV group) vs. 23.5 months (p = 0.04); OS: 67.0 (IV group) vs. 64.9 months (IP group) (p = n.s) | Significant PFS benefit with IP | |

| Pancreatic | Satoi et al. (2017) [70] | Phase II | IV PTX 50 mg/m2 + IP PTX 20 mg/m2 (days 1, 8) + oral S-1 80 mg/m2 (days 1–14 of 21 days cycle) | OS: 16.3 months 1-year OS 62%, 2-year 23%; overall response rate 36%, disease control rate 82% | Encouraging outcomes; conversion surgery led to longer OS (27.8 vs. 14.2 months) |

| Yamada et al. (2020) [4] | Phase I/II | IV GEM 800 mg/m2 + IV nab-PTX 75 mg/m2 + IP PTX 20 mg/m2 (days 1, 8, 15 of 21 days cycle) | RFS: 6 months OS: 14.5 months, response rate 50%, disease control rate 95%, cytology turned negative 39% | Good cytology conversion; OS longer in patients with conversion surgery | |

| Gastric | Yang XJ et al. 2011 [78] | Phase III RCT | CRS alone vs. CRS + HIPEC (CDDP 120 mg + MMC 30 mg) | OS: 6.5 in CRS group vs. 11.0 months (CRS + HIPEC group) (p = 0.046) | First RCT showing HIPEC significantly improves OS in GC patients with PMs. |

| Bonnot PE et al (2019) [23] | Phase III RCT | CRS alone vs. CRS + HIPEC (HIPEC regimen per study) | OS: 12.1 in CRS alone group vs. 18.8 months in CRS + HIPEC group, RFS: 7.8 vs. 13.6 months | Significantly better OS and RFS with HIPEC, especially in low-PCI and CC-0/1 patients | |

| Rau B et al (2024) [5] | Phase III RCT | CRS alone vs. CRS + HIPEC (CDDP 75 mg/m2 + MMC 15 mg/m2) | OS: 14.9 in CRS group vs 14.9 months in CRS + HIPEC group (p = 0.16); PFS: 3.5 vs. 7.1 months (p = 0.047) | PFS not OS significantly improved with HIPEC | |

| Ishigami H et al. (2010) [79] | Phase II | IV PTX 50 mg/m2 + IP PTX 20 mg/m2 (days 1, 8 of 21days cycle) + S-1 80 mg/m2 (days 1–14) | Median OS 22.5 months; 1-year OS 78%; overall response rate 56%; cytologyturned negative in 86% | High response rate and cytology clearance | |

| Ishigami H et al. (2018) [1] | Phase III RCT | IV PTX 50 mg/m2 + IP PTX 20 mg/m2 (days 1, 8 of 3 weeks cycle) + S-1 80 mg/m2 (days 1–21) in IP group vs. CDDP 60 mg/m2 (day 8 for a 5 weeks cycle) + S-1 80 mg/m2 (days 1 to 21) in SP group | OS: 15.2 in SP group vs. 17.7 months in IP group (p = 0.08) In sensitivity analysis adjusted for baseline ascites, OS in IP group is longer than SP group adjusted HR 0.59, p = 0.008. | Trend towards longer OS with IP group; benefit more apparent in adjusted analysis for ascites | |

| Colorectal | Verwaal VJ et al. (2003) [3] | Phase III RCT | 5FU-LV with or without palliative surgery vs. CRS + HIPEC with MMC +5-FU/LV | OS: 12.6 in 5FU-LV alone group vs. 22.3 months in HIPEC group (p = 0.032) | Significant survival benefit with CRS + HIPEC, especially in patients with limited tumor |

| Quénet F et al. (2021) [94] | Phase III RCT | CRS alone vs. CRS + HIPEC with L-OHP | OS: 41.2 in CRS alone vs. 41.7 months in CRS + HIPEC group (p = n.s) | No additional OS benefit from CRS +HIPEC | |

| Pseudomyxoma | Prabhu A et al. (2020) [102] | Phase II | Laparoscopic HIPEC with L-OHP 200 mg/m2 + IP docetaxel 40 mg/m2 + IP CDDP 40 mg/m2 + S-1 | 81.5% of patients qualified for CRS and HIPEC | High downstaging rate showed. |

| Tumor Type | Author, Year | Grade ≥ 3 Adverse Events (Type, %) | Catheter-Related Complications (%) | Treatment-Related Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian | Alberts et al. (1996) [57] | Anemia 25% (IV group), vs. 26% (IP group), neutropenia 69 vs. 56%, leukopenia 50 vs. 40%, thrombocytopenia, 9 vs. 8% | 5 patients (1.8%): Details are not reported. | 0% in IV group vs. 0.7% due to respiratory failure and bronchopneumonia in IP group IV group |

| Markman et al. (1998) [58] | Higher incidence of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and gastrointestinal and metabolic toxicities in IP group. (grade and % are not described) | — (not reported) | — | |

| Armstrong et al. (2006) [59] | Markedly increased incidences of fatigue (18%), pain (11%), infection (16%), fever (9%), leukopenia (76%), thrombocytopenia (12%), genitourinary event (7%), gastrointestinal event (46%), metabolic event (27%), pain (11%) and neurotoxicity (19%) in IP arm | Infection (10.2%), catheter obstruction (4.8%), catheter leak (1.4%), access problem (2.4%), fluid leak out vagina (0.4%) | 1.9% in IV group vs. 2.4% in IP group. All cases are attributed to infection. | |

| Nagao et al. (2020) [2] | 96% in IV group and 93.2% in IP group. Main AEs are anemia 67% vs. 64%, neutropenia 82% vs. 80%, thrombocytopenia 26% vs. 27%, abdominal pain 0% vs. 1.4%, nausea 2.7% vs. 1%, fatigue 1.3% vs. 1.7% and neuro system disorders 5.4% vs. 2.4% | catheter obstruction (2.7%), IP site leakage (5.7%) | 0% | |

| Pancreatic | Satoi et al. (2017) [70] | Hematologic AEs: neutropenia (42%), leukopenia (18%), febrile neutropenia (6%), and anemia (3%). Non-hematologic AEs: appetite loss (12%), nausea (9%), vomiting, diarrhea, mucositis (6%). | Infection (3%), dislocation of the device (6%) | 3% due to superior mesenteric arterial thrombosis |

| Yamada et al. (2020) [4] | Hematologic AEs: leucocytopenia (48%), neutropenia (70%), febrile neutropenia (9%), anaemia (17%) and thrombocytopenia (13%). Non-hematologic AEs: appetite loss (9%) and nausea (4%). | 1 patient (2.1%): Details are not reported. | — | |

| Gastric | Yang XJ et al. 2011 [78] | 4 patients (11.7%) in CRS group vs. 5 (14.7%) patients in the CRS + HIPEC group (p = n.s). The contents are infection, respiratory failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, bone marrow suppression and intestinal obstruction. | — | — |

| Bonnot PE et al (2019) [23] | 55.3% in CRS alone vs. 53.7% in CRS + HIPEC (p = 0.49): Details are not reported. | — | 90-days mortality: 7.4% in CRS alone vs. 10.1% in CRS + HIPEC (p = 0.82) | |

| Rau B et al (2024) [5] | Similar incidence: 38.1% in CRS alone vs. 43.6% in CRS + HIPEC (p = 0.79). | — | 0% in CRS alone vs. 4% in CRS + HIPEP (p = 0.49) | |

| Ishigami H et al. (2010) [79] | Neutropenia 38%, leukopenia 18% and anemia 10% | 1 patient (2.5%): catheter obstruction | 0% | |

| Ishigami H et al. (2018) [1] | Leukopenia 9% in SP group vs. 25% in IP group (p = 0.02), neutropenia 30% vs. 50% (p = 0.02); nonhematologic AEs are no differences between two group. | port infection 2.5%, catheter obstruction 2.5%, subcutaneous hematoma 0.8% and fistula between the catheter and small intestine 0.8% | 0% | |

| Colorectal | Verwaal VJ et al. (2003) [3] | Fever 6%, leukopenia 17%, thrombocytopenia 4%, neuropathy 4%, pulmonary embolus 4%, renal obstruction 4%, heart failure 12%, gastrointestinal fistula 15%, hemorrhage 14%, psychological disorders 10% in HIPEC group | Catheter infections 6% | 8% due to abdominal pain followed by HIPEC (2%) or postoperative complications (2%) |

| Quénet F et al. (2021) [94] | The incidences at 30 days were no difference between 32% in CRS alone group and 42% in CRS + HIPEC group (p = 0.08). However, at 60 days, events in CRS + HIPEC group were more than CRS alone (26% vs. 15%, p = 0.03) | — | At 30 days, 2 patients (1.5%) in each group. At 60 days, one additional patients (total 2.2%) in CRS alone group due to acute respiratory distress and two patients (total 3%) in CRS alone group due to pulmonary embolism and bilateral pneumonia. | |

| Pseudomyxoma | Prabhu A et al. (2020) [102] | Major morbidity 13.6% | 6% details are not reported. | 4.5% details are not reported. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tamura, K.; Kitayama, J.; Saga, Y.; Takei, Y.; Fujiwara, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Nagai, R.; Aizawa, K. Combined Intraperitoneal and Systemic Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Metastases: Drug Delivery Concepts, Pharmacokinetics, and Clinical Applications: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020179

Tamura K, Kitayama J, Saga Y, Takei Y, Fujiwara H, Yamaguchi H, Nagai R, Aizawa K. Combined Intraperitoneal and Systemic Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Metastases: Drug Delivery Concepts, Pharmacokinetics, and Clinical Applications: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(2):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020179

Chicago/Turabian StyleTamura, Kohei, Joji Kitayama, Yasushi Saga, Yuji Takei, Hiroyuki Fujiwara, Hironori Yamaguchi, Ryozo Nagai, and Kenichi Aizawa. 2026. "Combined Intraperitoneal and Systemic Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Metastases: Drug Delivery Concepts, Pharmacokinetics, and Clinical Applications: A Narrative Review" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 2: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020179

APA StyleTamura, K., Kitayama, J., Saga, Y., Takei, Y., Fujiwara, H., Yamaguchi, H., Nagai, R., & Aizawa, K. (2026). Combined Intraperitoneal and Systemic Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Metastases: Drug Delivery Concepts, Pharmacokinetics, and Clinical Applications: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceutics, 18(2), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020179