The Effect of GLP-1 Agonists on Patients with Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Outcomes

3.5. Effect on Liver Steatosis, Steatohepatitis, and Liver Fibrosis

3.6. Weight and HbA1c

3.7. Biomarkers and Liver Enzymes

3.8. Quality of Life and Adverse Events

3.9. Publication Bias

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Clinical Implications

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riazi, K.; Azhari, H.; Charette, J.H.; Underwood, F.E.; King, J.A.; Afshar, E.E.; Swain, M.G.; Congly, S.E.; Kaplan, G.G.; Shaheen, A.A. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golabi, P.; Paik, J.M.; AlQahtani, S.; Younossi, Y.; Tuncer, G.; Younossi, Z.M. Burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa: Data from Global Burden of Disease 2009–2019. J. Hepatol 2021, 75, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Stepanova, M.; Ong, J.; Trimble, G.; AlQahtani, S.; Younossi, I.; Ahmed, A.; Racila, A.; Henry, L. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Is the Most Rapidly Increasing Indication for Liver Transplantation in the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 580–589.e585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caturano, A.; Acierno, C.; Nevola, R.; Pafundi, P.C.; Galiero, R.; Rinaldi, L.; Salvatore, T.; Adinolfi, L.E.; Sasso, F.C. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From Pathogenesis to Clinical Impact. Processes 2021, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Gomez, E.; Martinez-Perez, Y.; Calzadilla-Bertot, L.; Torres-Gonzalez, A.; Gra-Oramas, B.; Gonzalez-Fabian, L.; Friedman, S.L.; Diago, M.; Romero-Gomez, M. Weight Loss Through Lifestyle Modification Significantly Reduces Features of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 367–378.e365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Alejandre, B.A.; Cantero, I.; Perez-Diaz-del-Campo, N.; Monreal, J.I.; Elorz, M.; Herrero, J.I.; Benito-Boillos, A.; Quiroga, J.; Martinez-Echeverria, A.; Uriz-Otano, J.I.; et al. Effects of two personalized dietary strategies during a 2-year intervention in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized trial. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1532–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevola, R.; Epifani, R.; Imbriani, S.; Tortorella, G.; Aprea, C.; Galiero, R.; Rinaldi, L.; Marfella, R.; Sasso, F.C. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frías, J.P.; Davies, M.J.; Rosenstock, J.; Pérez Manghi, F.C.; Fernández Landó, L.; Bergman, B.K.; Liu, B.; Cui, X.; Brown, K. Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide Once Weekly in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xia, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y. Efficacy of Incretin-Based Therapies in Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 40, 2659–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Morandin, R.; Fiorio, V.; Lando, M.G.; Stefan, N.; Tilg, H.; Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Improve MASH and Liver Fibrosis: A Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Liver Int. 2025, 45, e70256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Li, J.; Zeng, H.; Liu, J. Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on the degree of liver fibrosis and CRP in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim. Care Diabetes 2024, 18, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.A.; Browne, S.K.; Suschak, J.J.; Tomah, S.; Gutierrez, J.A.; Yang, J.; Roberts, M.S.; Harris, M.S. Effect of pemvidutide, a GLP-1/glucagon dual receptor agonist, on MASLD: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Bedossa, P.; Fraessdorf, M.; Neff, G.W.; Lawitz, E.; Bugianesi, E.; Anstee, Q.M.; Hussain, S.A.; Newsome, P.N.; Ratziu, V.; et al. A Phase 2 Randomized Trial of Survodutide in MASH and Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Kaplan, L.M.; Frias, J.P.; Brouwers, B.; Wu, Q.; Thomas, M.K.; Harris, C.; Schloot, N.C.; Du, Y.; Mather, K.J.; et al. Triple hormone receptor agonist retatrutide for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A randomized phase 2a trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2037–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, S.S.; Daniels, S.J.; Robertson, D.; Sarv, J.; Sánchez, J.; Carter, D.; Jermutus, L.; Challis, B.; Sanyal, A.J. Safety and Efficacy of Novel Incretin Co-agonist Cotadutide in Biopsy-proven Noncirrhotic MASH with Fibrosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Gaunt, P.; Aithal, G.P.; Barton, D.; Hull, D.; Parker, R.; Hazlehurst, J.M.; Guo, K.; Abouda, G.; Aldersley, M.A.; et al. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet 2016, 387, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xu, W.; Yang, H.; Feng, W.; Li, C.; Tong, G.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Shen, S.; et al. Effects of exenatide, insulin, and pioglitazone on liver fat content and body fat distributions in drug-naive subjects with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2014, 51, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutour, A.; Abdesselam, I.; Ancel, P.; Kober, F.; Mrad, G.; Darmon, P.; Ronsin, O.; Pradel, V.; Lesavre, N.; Martin, J.C.; et al. Exenatide decreases liver fat content and epicardial adipose tissue in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes: A prospective randomized clinical trial using magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2016, 18, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, A.; Andersen, G.; Hockings, P.; Johansson, L.; Morsing, A.; Palle, M.S.; Vogl, T.; Loomba, R.; Plum-Mörschel, L. Randomised clinical trial: Semaglutide versus placebo reduced liver steatosis but not liver stiffness in subjects with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54, 1150–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Tian, W.; Lin, L.; Xu, X. Liraglutide or insulin glargine treatments improves hepatic fat in obese patients with type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in twenty-six weeks: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 170, 108487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Gao, L.; Xue, H.; Tian, J.; Wang, K.; Jiang, H.; Huang, C.; Lian, Q.; Yuan, M.; Gao, G.; et al. Efficacy and safety of a biased GLP-1 receptor agonist ecnoglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, J.; Hsiang, J.C.; Taneja, R.; Koo, S.; Soon, G.; Kam, C.J.; Law, N.; Ang, T. Randomized trial comparing effects of weight loss by liraglutide with lifestyle modification in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchay, M.S.; Krishan, S.; Mishra, S.K.; Choudhary, N.S.; Singh, M.K.; Wasir, J.S.; Kaur, P.; Gill, H.K.; Bano, T.; Farooqui, K.J.; et al. Effect of dulaglutide on liver fat in patients with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD: Randomised controlled trial (D-LIFT trial). Diabetologia 2020, 63, 2434–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yan, H.; Xia, M.; Zhao, L.; Lv, M.; Zhao, N.; Rao, S.; Yao, X.; Wu, W.; Pan, B.; et al. Efficacy of exenatide and insulin glargine on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Armstrong, M.J.; Jara, M.; Kjær, M.S.; Krarup, N.; Lawitz, E.; Ratziu, V.; Sanyal, A.J.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. Semaglutide 2·4 mg once weekly in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-related cirrhosis: A randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Hartman, M.L.; Lawitz, E.J.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Boursier, J.; Bugianesi, E.; Yoneda, M.; Behling, C.; Cummings, O.W.; Tang, Y.; et al. Tirzepatide for Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatohepatitis with Liver Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolla, A.; Poolman, T.; Othonos, N.; Dong, J.; Smith, K.; Cornfield, T.; White, S.; Ray, D.W.; Mouchti, S.; Mózes, F.E.; et al. Randomised trial comparing weight loss through lifestyle and GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy in people with MASLD. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, P.N.; Buchholtz, K.; Cusi, K.; Linder, M.; Okanoue, T.; Ratziu, V.; Sanyal, A.J.; Sejling, A.-S.; Harrison, S.A. A placebo-controlled trial of subcutaneous semaglutide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Newsome, P.N.; Kliers, I.; Østergaard, L.H.; Long, M.T.; Kjær, M.S.; Cali, A.M.; Bugianesi, E.; Rinella, M.E.; Roden, M.; et al. Phase 3 Trial of Semaglutide in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2089–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, M.M.; Tonneijck, L.; Muskiet, M.H.A.; Kramer, M.H.H.; Pouwels, P.J.W.; Pieters-van den Bos, I.C.; Hoekstra, T.; Diamant, M.; van Raalte, D.H.; Cahen, D.L. Twelve week liraglutide or sitagliptin does not affect hepatic fat in type 2 diabetes: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 2588–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Yao, B.; Kuang, H.; Yang, X.; Huang, Q.; Hong, T.; Li, Y.; Dou, J.; Yang, W.; Qin, G.; et al. Liraglutide, Sitagliptin, and Insulin Glargine Added to Metformin: The Effect on Body Weight and Intrahepatic Lipid in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2019, 69, 2414–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gómez, M.; Armstrong, M.J.; Funuyet-Salas, J.; Mangla, K.K.; Ladelund, S.; Sejling, A.S.; Shrestha, I.; Sanyal, A.J. Improved health-related quality of life with semaglutide in people with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomised trial. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 58, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okanoue, T.; Sundby Palle, M.; Sejling, A.S.; Tawfik, M.; Roden, M. Similar weight loss with semaglutide regardless of diabetes and cardiometabolic risk parameters in individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Post hoc analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L. Hepatic Fibrosis and Cancer: The Silent Threats of Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; de Avila, L.; Petta, S.; Hagström, H.; Kim, S.U.; Nakajima, A.; Crespo, J.; Castera, L.; Alkhouri, N.; Zheng, M.H.; et al. Predictors of fibrosis, clinical events and mortality in MASLD: Data from the Global-MASLD study. Hepatology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.M.; McCauley, K.F.; Dunham-Snary, K.J. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): Mechanisms, Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Advances. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2025, 8, e70132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, R.F.; Tacke, F.; Sugimoto, A.; Friedman, S.L. Antifibrotic therapies for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kowdley, K.V.; Terrault, N.; Chalasani, N.P.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; McCullough, A.J.; Shringarpure, R.; Ferguson, B.; Lee, L.; et al. Factors Associated with Histologic Response in Adult Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 88–95.e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Hu, J.; Han Chin, Y.; Chew, H.S.J.; Wang, W. Comparative effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor agonists and dual agonists in the treatment of patients with metabolic dysfunction associated steatohepatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1681965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutoukidis, D.A.; Koshiaris, C.; Henry, J.A.; Noreik, M.; Morris, E.; Manoharan, I.; Tudor, K.; Bodenham, E.; Dunnigan, A.; Jebb, S.A.; et al. The effect of the magnitude of weight loss on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2021, 115, 154455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, A.S.; Crowley, M.J.; Wang, Y.; Moylan, C.A.; Guy, C.D.; Henao, R.; Piercy, D.L.; Seymour, K.A.; Sudan, R.; Portenier, D.D.; et al. Glycemic Control Predicts Severity of Hepatocyte Ballooning and Hepatic Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2021, 74, 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, K.; Roghani, R.S.; Camilleri, M. Effects of GLP-1 agonists on proportion of weight loss in obesity with or without diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Med. 2022, 35, 100456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, S.; Tahrani, A.A.; Piya, M.K. The role of GLP-1 receptor agonists as weight loss agents in patients with and without type 2 diabetes. Pract. Diabetes 2015, 32, 297–300b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgojo-Martínez, J.J.; Mezquita-Raya, P.; Carretero-Gómez, J.; Castro, A.; Cebrián-Cuenca, A.; de Torres-Sánchez, A.; García-de-Lucas, M.D.; Núñez, J.; Obaya, J.C.; Soler, M.J.; et al. Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromrey, M.L.; Ittermann, T.; Berning, M.; Kolb, C.; Hoffmann, R.T.; Lerch, M.M.; Völzke, H.; Kühn, J.P. Accuracy of ultrasonography in the assessment of liver fat compared with MRI. Clin. Radiol. 2019, 74, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoncapè, M.; Liguori, A.; Tsochatzis, E.A. Non-invasive testing and risk-stratification in patients with MASLD. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 122, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinitz, S.; Müller, J.; Jenderka, K.V.; Schlögl, H.; Stumvoll, M.; Blüher, M.; Blank, V.; Karlas, T. The application of high-performance ultrasound probes increases anatomic depiction in obese patients. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Groups | No of Participants | Age in Years Mean (SD) | Male (%) | BMI (kg/m2) Mean (SD) | Weight (KG) Mean (SD) | Type 2 Diabetes (%) | HbA1c % Mean (SD) | Hepatic Fat Content Mean (SD) | ALT (U/L) Mean (SD) | AST (U/L) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrong et al. 2016 [20] | Liraglutide | 26 | 50 (11) | 18 (69%) | 34.2 (4.7) | 101 (18) | 9 (35%) | 5.9 (0.7) | N/A | 77 (34) | 51 (22) |

| Placebo | 26 | 52 (12) | 13 (50%) | 37.7 (6.2) | 108 (18) | 8 (31%) | 6.0 (0.9) | N/A | 66 (42) | 51 (27) | |

| Bi et al. 2014 [21] | Exenatide | 11 | 50.8 (13.3) | 7 (63.6%) | 25.1 (3.6) | 71.1 (11.6) | 11 (100%) | 8.6 (1.3) | 27.4 (18.2) | 30.7 (17.6) | 26.3 (9.3) |

| Insulin | 11 | 53.5 (8) | 5 (45.5%) | 24.5 (2) | 65.2 (6.6) | 11 (100%) | 9.1 (1) | 3.7 (16.6) | 20.2 (6.6) | 23.0 (7) | |

| Dutour et al. 2016 [22] | Exenatide | 22 | 51 (9.4) | 13 (59%) | 37.2 (8.4) | 104 (23.5) | 22 (100%) | N/A | N/A | 48 (35) | 33 (25) |

| Reference treatment | 22 | 52 (9.4) | 8 (36%) | 35 (5.6) | 95 (14) | 22 (100%) | N/A | N/A | 48 (27) | 30 (13) | |

| Flint et al. 2021 [23] | Semaglutide | 34 | 59.5 (10.1) | 23 (67.6%) | N/A | 105.1 (15.3) | 7.3 (0.9%) | 7.3 (0.9) | 22.1 (15.6) | 53.6 (47.8) | 38.1 (27.2) |

| Placebo | 33 | 60.5 (8.5) | 24 (72.7%) | N/A | 102.3 (12.7) | 7.4 (1%) | 7.4 (1.0) | 20.9 (14.2) | 44.4 (34.7) | 34.2 (21.5) | |

| Guo et al. 2020 [24] | Liraglutide | 31 | 53.1 (6.3) | 16 (52%) | 29.2 (4.2) | 84.3 (10.8) | 31 (100%) | 7.5 (1.3) | 26.4 (3.2) | 33.2 (15.8) | 29.6 (10.8) |

| Insulin | 30 | 52.0 (8.7) | 18 (60%) | 28.3 (3.8) | 83.8 (11.2) | 30 (100%) | 7.4 (0.9) | 25(4.3) | 31.5 (12.6) | 27.9 (12.1) | |

| Placebo | 30 | 52.6 (3.9) | 20 (67%) | 28.6 (3.7) | 82.2 (12.4) | 30 (100%) | 7.4 (1) | 25.8 (4.5) | 30.5 (13.4) | 28.1 (12.6) | |

| Harrison et al. 2025 [13] | Pemvidutide | 70 | 49.2 (9.3) | 34 (48.6%) | 35.7 (4.8) | 99.81 (17.7) | 21 (30%) | 6.8 (1.2) | 21.2 (7.4) | 35.6 (18.5) | 25.8 (10) |

| Placebo | 24 | 47.9 (14) | 10 (41.67%) | 36.9 (4.7) | 105.1 (20.8) | 6 (5%) | 6.2 (0.6) | 23.8 (9.2) | 39.5 (21.4) | 23.8 (10.0) | |

| Ji et al. 2025 [25] | Ecnoglutide | 499 | 34.4 (7.6) | 253 (50.7%) | 32.5 (4.1) | 91.4 (16.1) | 0 | 5.3 (0.3) | 28.5 (17) | 20.6 (7.2) | |

| Placebo | 165 | 33.8 (7.2) | 82 (50%) | 32.4 (4.1) | 91.0 (16.3) | 0 | 5.3 (0.4) | 26 (3.3) | 1 9 (1.5) | ||

| Khoo et al. 2019 [26] | Liraglutide | 15 | 38.6 (8.2) | 15 (100%) | 34.3 (3.9) | 102.7 (16.2) | 0 | N/A | 31.4 (9.3) | 87 (32) | 45 (14) |

| Lifestyle interventions | 15 | 43.6 (9.9) | 13 (87%) | 32.2 (3.2) | 89.6 (12.7) | 0 | N/A | 30.8 (17.5) | 88 (38) | 52 (27) | |

| Kuchay et al. 2020 [27] | Dulaglutide | 32 | 46.6 (9.1) | 23 (72%) | 29.6 (3.6) | 85.8 (13.3) | 32 (100%) | 8.4 (1) | 17.9 (7.2) | 70.1 (30.1) | 49.9 (22.7) |

| Usual care | 32 | 48.1 (8.9) | 22 (69%) | 29.9 (3.9) | 83.7 (13) | 32 (100%) | 8.4 (1) | 17.1 (7.7) | 68.1 (30.8) | 46.1 (21.1) | |

| Liu et al. 2020 [28] | Exentide | 35 | 47.63 (10.14) | 19 (54%) | 28.49 (3.02) | 79.28 (9.64) | 35 (100%) | 8.32 (0.94) | 42.21 (16.83) | 42.71 (23.19) | 31.29 (17.32) |

| Insulin | 36 | 50.56 (11.78) | 19 (53%) | 27.84 (3.10) | 77.63 (13.70) | 36 (100%) | 8.58 (0.91) | 35.47 (13.78) | 32.81 (22.37) | 25.11 (14.09) | |

| Loomba et al. 2023 [29] | Semaglutide | 47 | 59.9 (7.1) | 16 (34%) | 34.6 (5.9) | 95.2 (18.7) | 35 (75%) | 7.1 (1.3) | 11.34 (5.04) | 56.1 (39.4) | 51.9 (24.2) |

| Placebo | 24 | 58.7 (9.7) | 6 (25%) | 35.5 (6.0) | 98.6 (22.2) | 18 (75%) | 7.2 (1.2) | 11.65 (5.23) | 41.8 (23.5) | 42.9 (20.3) | |

| Loomba et al. 2024 [30] | Tirzepatide | 142 | 54.7 (11.2) | 60 (42.3%) | 36.2 (6) | 101.1 (21.4) | 82 (57.7%) | 6.5 (1.1) | 18.5 (7.6) | 62.6 (34.2) | 50 (24.5) |

| Placebo | 48 | 53.5 (11.6) | 21 (43.8%) | 36 (6.7) | 96 (21.6) | 29 (60%) | 6.8 (1.2) | 18.2 (6.8) | 59.7 (30.3) | 52.3 (21.3) | |

| Moolla et al. 2025 [31] | Liraglutide | 15 | 48 (15.5) | 8 (53.3%) | 35.7 (6.6) | 106.9 (21.7) | 0 | N/A | 24.3 (8.9) | 58 (31) | 36 (11.6) |

| Lifestyle interventions | 14 | 48 (15) | 7 (50%) | 36.4 (5.6) | 104.2 (21.7) | 0 | N/A | 21.1 (9) | 61 (29.9) | 37 (15) | |

| Newsome et al. 2021 [32] | Semaglutide | 240 | 55.8 (10.4) | 90 (37.5%) | 35.7 (2.3) | 97.4 (21) | 149 (62.1%) | 7.3 (1.2) | N/A | 70.6 (59.5) | 55.3 (43) |

| Placebo | 80 | 52.4 (10.8) | 36 (45%) | 36.2 (2.4) | 101.3 (23.3) | 50 (62%) | 7.3 (1.2) | N/A | 74.7 (68.8) | 54.6 (45.3) | |

| Sanyal et al. 2024 a [15] | Retatrutide | 79 | 46.8 (12.3) | 43 (87.8%) | 38.4 (5.3) | 110.1 (19.1) | N/A | 5.5 (0.4) | 20 (6.9) | 33.2 (4) | 24.2 (1.8) |

| Placebo | 19 | 45.5 (10.7) | 9 (47.4%) | 38.6 (4.6) | 110.8 (16.5) | N/A | 5.56 (0.33) | 15.6 (5.8) | 31.6 (2.1) | 24.5 (1.2) | |

| Sanyal et al. 2024 b [14] | Survodutide | 219 | 50.1 (13.2) | 108 (49.3%) | 35.9 (6.4) | 101.8 (22.9) | 84 (38.4%) | 6.9 (1) | 19.5 (7.5) | 57.9 (43.5) | 45.9 (34.9) |

| Placebo | 74 | 53 (11.5) | 30 (40.5%) | 35.49 (6.44) | 98.09 (20.78) | 29 (39%) | 7.08 (0.87) | 19.62 (7.59) | 57.3 (36.6) | 51.3 (40.9) | |

| Sanyal et al. 2025 [33] | Semaglutide | 534 | 56.3 (11.4) | 221 (41.3%) | 34.3 (7.2) | 95.4 (24.5) | 296 (55.4%) | N/A | N/A | 67.8 (42.3) | 53.2 (28.6) |

| Placebo | 266 | 55.4 (12) | 122 (45.8%) | 35 (7.1) | 97.6 (24.6) | 296 (55.4%) | N/A | N/A | 67.9 (44.7) | 52.8 (33.1) | |

| Shankar et al. 2024 [16] | Cotadutide | 50 | 57.7 (11.2) | 23 (46%) | 37.2(6.2) | 99.3(18.8) | 29 (58%) | 6.7 (1.2) | 19.5 (7.5) | 44.8(20.8) | 35.1 (15.3) |

| Placebo | 24 | 52.2 (13.5) | 10 (41.7%) | 37.6 (5.1) | 102.2 (18.1) | 12 (50%) | 6.8 (1.5) | 19.1 (8.2) | 48.8 (31.2) | 38.4 (24.6) | |

| Smits et al. 2016 [34] | Liraglutide | 17 | 60.8 (7.4) | 12 (70.6%) | 32.8 (4.1) | 103.2 (13.2) | 17 (100%) | 7.4 (0.8) | 20.9 (14) | 28.9 (12) | 24.2 (7.8) |

| Placebo | 17 | 65.8 (5.8) | 13 (76.5%) | 30.6 (2.9) | 95.8 (9.9) | 17 (100%) | 7.5 (0.8) | 18.7 (11.1) | 32 (21.4) | 22.2 (7.4) | |

| Yan et al. 2019 [35] | Liraglutide | 24 | 43.1 (9.7) | 17 (70.8%) | 30.1 (3.3) | 86.6 (12.9) | 24 (100%) | 7.8 (1.4) | 15.4 (5.6) | 43.2 (21.2) | 31.1 (11.7) |

| Insulin | 24 | 45.6 (7.6) | 14 (58.3%) | 29.6 (3.5) | 85.6 (14.2) | 24 (100%) | 7.7 (0.9) | 14.9 (5.5) | 39.5 (25.7) | 33.2 (17.4) |

| Study ID | Country | NCT | Population | T2DM | NASH | Sample | Intervention | Dose and Frequency | Control | MRI or Biopsy | Follow up Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrog et al. 2016 [20] | United Kingdom | NCT01237119 | Patients with biopsy-confirmed non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | Both patients with and without diabetes | Yes | 52 | Liraglutide | 1.8 mg daily | Placebo | Biopsy | 48 weeks |

| Bi 2014 [21] | China | NCT01147627 | Drug-naive T2DM patients | Yes | No | 33 | Exentide | 10 lg twice daily | Insulin, pioglitazone | MRI | 24 weeks |

| Dutour et al. 2016 [22] | France | NR | Obese subjects with T2D and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels of 6.5–10% | Yes | No | 44 | Exenatide | 10 µg twice daily | Reference treatment | MRI | 26 weeks |

| Flint et al. 2021 [23] | Germany | NCT03357380 | Subjects aged 18–75 years, with a BMI of 25–40 kg/m2 and liver stiffness of 2.50–4.63 kPa measured by MRE and >4.0 kPa | Both patients with and without diabetes | No | 67 | Semaglutide | 0.4 mg/day | Placebo | MRI | 48 weeks |

| Guo et al. 2020 [24] | China | hiCTR2000035091 | Patients with type 2 diabetes and NAFL | Yes | No | 96 | Liraglutide | 1.8 mg | Insulin, placebo | MRI | 26 weeks |

| Harrison et al. 2025 [13] | United States | NCT05006885 | Patients with a BMI >−28.0 kg/m2 and LFC >−10% | Both patients with and without diabetes | No | 94 | Pemvidutide | 1.2, 1.8, and 2.4 mg | Placebo | MRI | 12 weeks |

| Ji et al. 2025 [25] | China | NCT05813795 | Adults with overweight or obesity | No | No | 664 | Ecnoglutide | 1.2, 1.8, and 2.4 mg | Placebo | MRI | 40 weeks |

| Khoo et al. 2019 [26] | Singapore | NR | Obese adults with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | No | No | 30 | Liraglutide | 3 mg | Lifestyle intervention | MRI | 26 weeks |

| Kuchay et al. 2020 [27] | India | NCT03590626 | Patients with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD | Yes | No | 64 | Dulaglutide | Dulaglutide 1.5 mg weekly | Usual care | MRI | 24 weeks |

| Liu et al. 2020 [28] | China | NCT02303730 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | Yes | No | 71 | Exenatide | Subcutaneous exenatide 10 μg twice daily for 20 weeks | Insulin | MRI | 24 weeks |

| Loomba et al. 2023 [29] | Europe and the USA | NCT03987451 | Patients with NASH and compensated cirrhosis. | Both patients with and without diabetes | Yes | 71 | Semaglutide | Once-weekly subcutaneous 2.4 mg | Placebo | Both | 48 weeks |

| Loomba et al. 2024 [30] | Multicenter (10 countries) | NCT04166773 | Participants with biopsy-confirmed MASH and stage F2 or F3 (moderate or severe) fibrosis | Both patients with and without diabetes | Yes | 190 | Tirzepatide | Doses of 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg once-weekly | Placebo | Biopsy | 52 weeks |

| Moolla et al. 2025 [31] | United Kingdom | EudraCT (2016-002045-36) | Participants with MASLD, without type 2 diabetes | No | Included a subpopulation | 29 | Liraglutide | Liraglutide treatment 1.8 mg/day | Lifestyle interventions | MRI | 12 weeks |

| Newsome et al. 2021 [32] | Multicenter (16 countries) | NCT02970942 | Patients with biopsy- confirmed NASH and liver fibrosis of stage F1, F2, or F3. | Both patients with and without diabetes | Yes | 320 | Semaglutide | Once-daily subcutaneous semaglutide at a dose of 0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 mg | Placebo | Biopsy | 72 weeks |

| Sanyal et al. 2024 a [15] | United States | NCT04881760 | Participants with MASLD | No | NR | 98 | Retatrutide | Retatrutide 1 mg, 4 mg, 8 mg, or 12 mg administered once-weekly | Placebo | MRI | 24 weeks |

| Sanyal et al. 2024 b [14] | Multicenter (25 countries) | NCT04771273 | Adults with biopsy-confirmed MASH and fibrosis | Both patients with and without diabetes | Yes | 293 | Survodutide | Once-weekly subcutaneous injections of survodutide at a dose of 2.4, 4.8, or 6.0 mg | Placebo | Both | 48 weeks |

| Sanyal et al. 2025 [33] | Multicenter (253 clinical sites in 37 countries) | NCT04822181 | Patients with biopsy-defined MASH and fibrosis | Both patients with and without diabetes | Yes | 800 | Semaglutide | Once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide at a dose of 2.4 mg | Placebo | Biopsy | 72 weeks |

| Shankar et al. 2024 [16] | 23 sites across the United States and Puerto Rico | NCT04019561 | Participants with biopsy- proven noncirrhotic metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) with fibrosis. | Both patients with and without diabetes | Yes | 74 | Cotadutide | Subcutaneous once-daily cotadutide 300 mg, cotadutide 600 mg20:K20 | Placebo | Both | 19 weeks |

| Smits et al. 2016 [34] | Netherlands | NCT01744236 | Overweight patients with type 2 diabetes | Yes | No | 51 | Liraglutide | Liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily | Placebo, sitagliptin | MRI | 12 weeks |

| Yan et al. 2019 [35] | China | NCT02147925 | Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | Yes | No | 75 | Liraglutide | Subcutaneous 1.8 mg once daily | Sitagliptin and insulin | MRI | 26-week |

| Main Analysis | Sensitivity Analysis (Leave-One-Out Test) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Comparison | No. of studies | Effect Estimate | Heterogeneity | Exclusion of | No. of studies | Effect estimate | Heterogeneity | ||||

| SMD, 95%CI/RR, 95%CI | p value | p value | I2 | SMD, 95%CI/RR, 95%CI | p value | p value | I2 | |||||

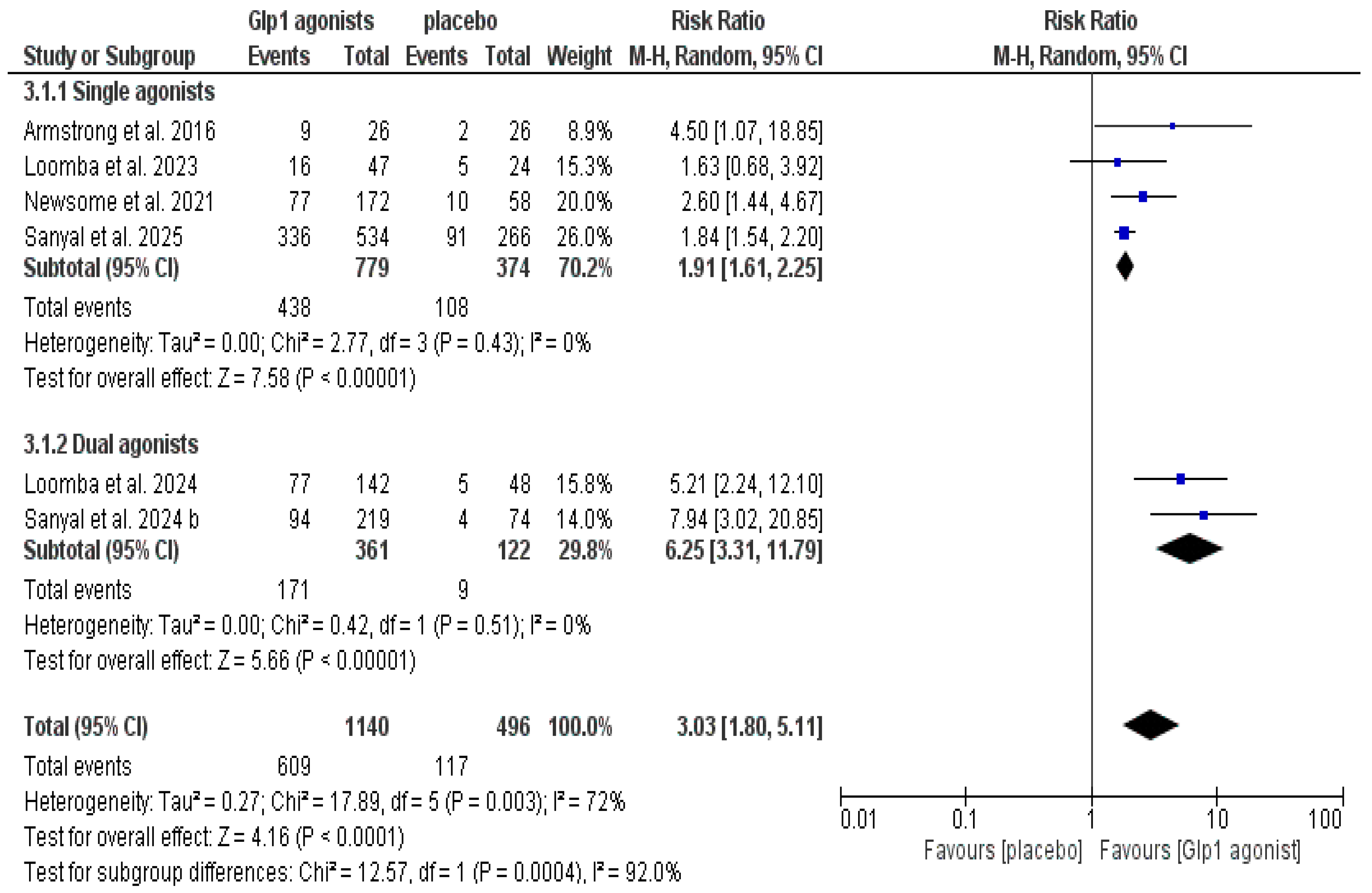

| Resolution of MASH without worsening fibrosis | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 6 | 3.03 [1.80, 5.11] | Test for overall effect: (p < 0.0001) | (p = 0.003) | I2 = 72% | Not resolved | N/A | ||||

| Improvement of at least one stage of liver fibrosis without worsening of MASH | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. placebo) | 5 | 1.45 [1.05, 1.99] | (p = 0.02) | (p = 0.05) | I2 = 59% | Loomba et al. 2023 [29] | 4 | 1.61 [1.34, 1.93] | (p < 0.00001) | p = 0.55 | I2 = 0% |

| Resolution of MASH and improvement in fibrosis | Overall population (Semaglutide vs. placebo) | 3 | 2.01 [1.55, 2.62] | (p < 0.00001) | (p = 0.18); | I2 = 41% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Weight | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 18 | −1.11 [−1.57, −0.66] | (p < 0.00001) | (p < 0.00001) | I2 = 95% | Not resolved | N/A | ||||

| HBA1c | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 15 | −0.81 [−1.16, −0.45] | (p < 0.00001) | (p < 0.00001) | I2 = 90% | Not resolved | N/A | ||||

| Liver fat | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 17 | −0.72 [−0.99, −0.45] | (p < 0.00001) | (p < 0.00001) | I2 = 78% | Not resolved | N/A | ||||

| AST | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 16 | −0.48 [−0.83, −0.13] | (p = 0.008) | (p < 0.00001); | I2 = 91% | Not resolved | N/A | ||||

| ALT | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 17 | −0.54 [−0.85, −0.23] | (p = 0.0008) | (p < 0.00001) | I2 = 89% | Not resolved | N/A | ||||

| CRP | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 4 | −0.54 [−0.90, −0.18] | (p = 0.004) | (p = 0.05) | I2 = 62% | Harrison et al. 2025 [13] | 3 | −0.67 [−1.03, −0.31] | (p = 0.0003) | (p = 0.17) | I2 = 44% |

| Quality of life SF-36 (physical component) | Overall population GLP-1 agonists vs. placebo) | 2 | 0.35 [0.12, 0.58] | (p = 0.003) | (p = 0.99) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Quality of life SF-36 (mental component) | Overall population GLP-1 agonists vs. placebo) | 2 | 0.14 [−0.09, 0.38] | (p = 0.23) | (p = 0.73) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Liver fat reduction ≥30% | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 6 | 3.32 [1.89, 5.83] | (p < 0.0001) | (p = 0.05) | I2 = 54% | Harrison et al. 2025 [13] | 5 | 2.95 [1.88, 4.63] | (p < 0.00001) | (p = 0.20) | I2 = 33% |

| Flint et al. 2021 [23] | 5 | 3.85 [2.05, 7.23] | (p < 0.0001) | (p = 0.15) | I2 = 40% | |||||||

| Liver fat reduction ≥70% | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 2 | 10.18 [2.32, 44.68] | (p = 0.002) | (p = 0.11) | I2 = 62% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Adverse events | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 11 | 1.10 [1.05, 1.14] | (p < 0.00001) | (p = 0.23) | I2 = 22% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Serious adverse events | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 12 | 1.13 [0.88, 1.44] | (p = 0.35) | (p = 0.98) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Hypoglycemia event | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 5 | 1.08 [0.72, 1.61] | (p = 0.71) | (p = 0.45) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Gastrointestinal side effects | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 5 | 1.51 [1.37, 1.67] | (p < 0.00001) | (p = 0.44) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Diarrhea | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 13 | 2.02 [1.67, 2.43] | (p < 0.00001) | (p = 0.70) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Nausea | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 13 | 2.98 [2.49, 3.58] | (p < 0.00001) | (p = 0.32) | I2 = 13% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Vomiting | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 12 | 4.76 [3.40, 6.66] | (p < 0.00001) | (p = 0.63) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Fatigue | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 7 | 1.52 [1.10, 2.10] | (p = 0.01) | (p = 0.80) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Dizziness | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 6 | 1.00 [0.47, 2.12] | (p = 0.99) | (p = 0.06) | I2 = 52% | Sanyal 2024 a [15] | 5 | 0.99 [0.67, 1.46] | (p = 0.97) | (p = 0.43) | I2 = 0% |

| Injection site reaction | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 4 | 1.01 [0.67, 1.51] | (p = 0.98) | (p = 0.76) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant heterogeneity | N/A | ||||

| Gallbladder events | Overall population (GLP-1 agonist vs. control) | 4 | 1.75 [0.87, 3.54] | (p = 0.12) | (p = 0.90) | I2 = 0% | Not performed since there is no significant | N/A | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tornea, D.A.; Goldis, C.; Isaic, A.; Motofelea, A.C.; Sima, A.C.; Ciocarlie, T.; Crintea, A.; Diaconescu, R.G.; Motofelea, N.; Goldis, A. The Effect of GLP-1 Agonists on Patients with Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010086

Tornea DA, Goldis C, Isaic A, Motofelea AC, Sima AC, Ciocarlie T, Crintea A, Diaconescu RG, Motofelea N, Goldis A. The Effect of GLP-1 Agonists on Patients with Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010086

Chicago/Turabian StyleTornea, Denisia Adelina, Christian Goldis, Alexandru Isaic, Alexandru Catalin Motofelea, Alexandra Christa Sima, Tudor Ciocarlie, Andreea Crintea, Razvan Gheorghe Diaconescu, Nadica Motofelea, and Adrian Goldis. 2026. "The Effect of GLP-1 Agonists on Patients with Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010086

APA StyleTornea, D. A., Goldis, C., Isaic, A., Motofelea, A. C., Sima, A. C., Ciocarlie, T., Crintea, A., Diaconescu, R. G., Motofelea, N., & Goldis, A. (2026). The Effect of GLP-1 Agonists on Patients with Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010086