Advancing Tuberculosis Treatment with Next-Generation Drugs and Smart Delivery Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods: Literature Search and Review Approach

3. New Horizons in Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Discovery

3.1. Innovative Small Molecules

3.2. Drug Repurposing and Adjunctive Antibacterials

3.3. Host-Directed Therapies (Hdts)

3.4. Emerging Biologic and Genetic Therapies

4. Innovative Delivery Systems in Tb Pharmaceutics

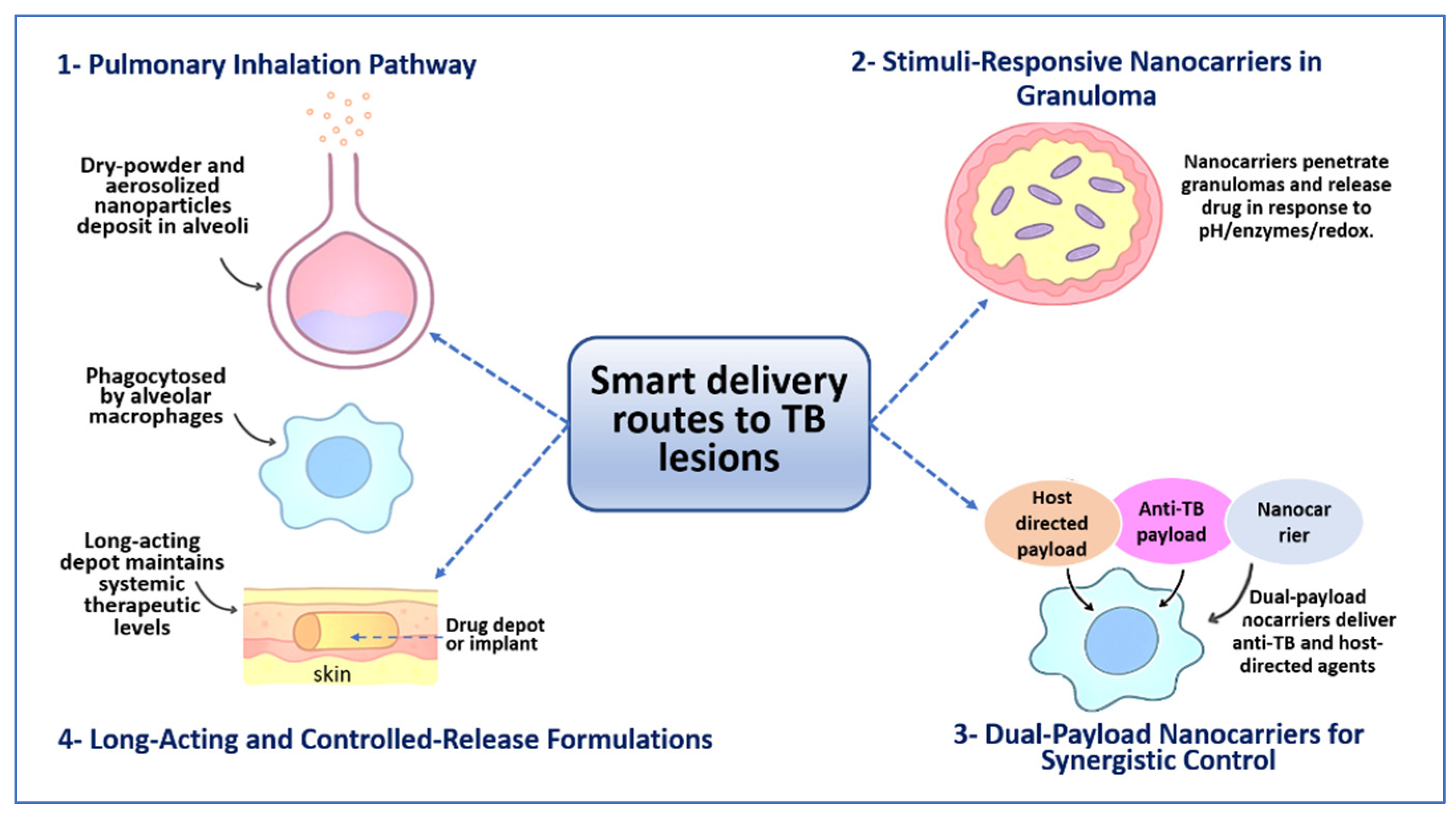

4.1. Pulmonary and Inhalable Delivery Systems

4.2. Nanocarrier-Based Systems

4.3. Stimuli-Responsive and Smart Delivery

4.4. Long-Acting and Controlled-Release Formulations

4.5. Co-Delivery and Combination Platforms

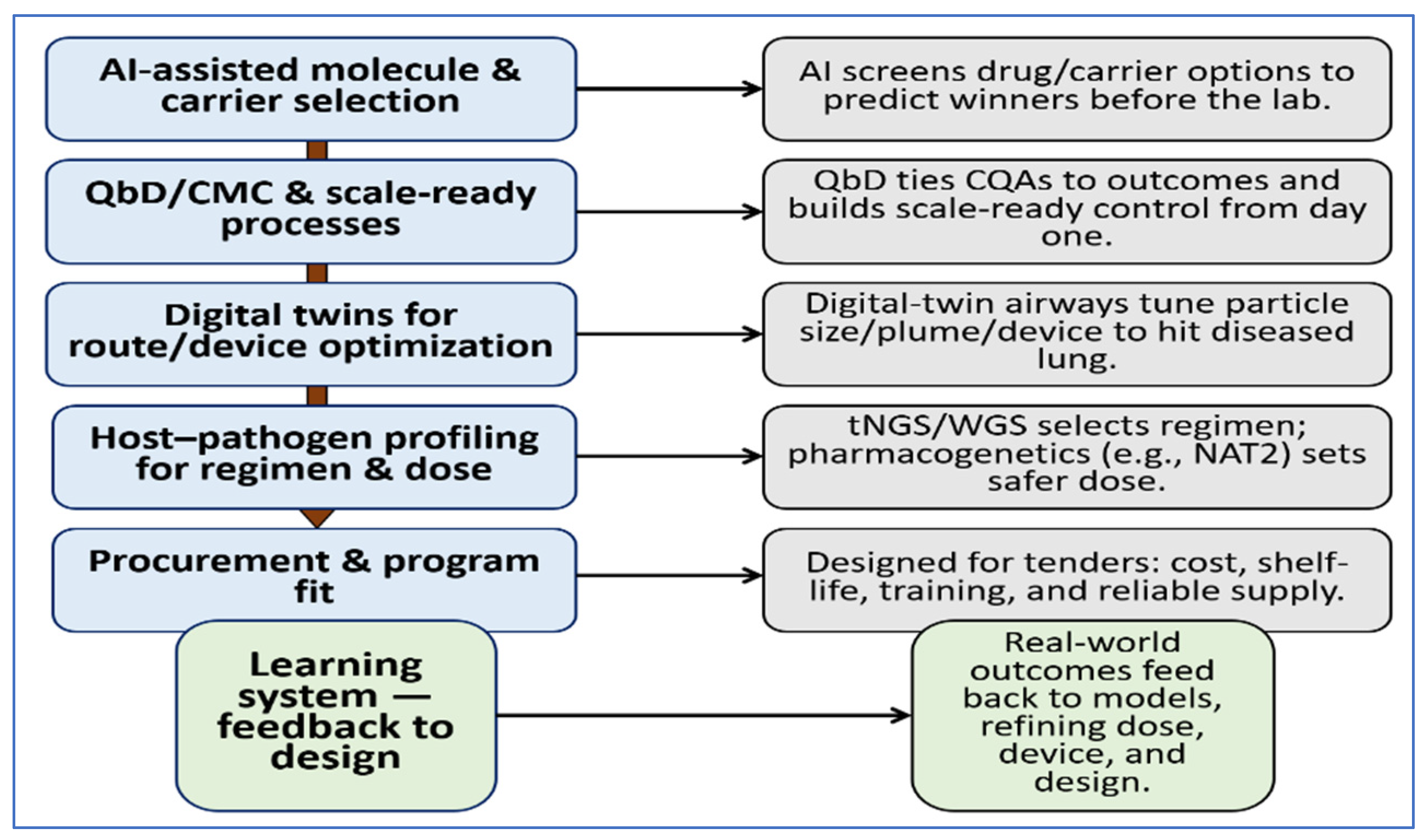

5. Bridging Therapeutics and Delivery: The Precision Pharmaceutic Paradigm

5.1. Case Studies: Improved PK/PD Through Delivery Innovation

5.2. AI and Computational Modeling in Drug Delivery Co-Optimization

5.3. Strategies for Intracellular Penetration and Sustained Exposure

5.4. Patient-Centered Issues: Adherence, Cost, Access

5.5. Synthesis and Future Directions

| Agent/Theme | Approach | Model/Setting | Key Findings | Practical Takeaway | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDQ: EBA PK/PD model | Mechanistic PK/PD re-analysis of 14-day EBA trial | Adults with drug-susceptible pulmonary TB; monotherapy dataset re-analyzed | BDQ produced measurable kill with estimated maximum rate near 0.23 log10 CFU/mL/day and EC50 near 1.6 mg/L | Exposure-aware dosing and delivery needed to balance efficacy and safety | [156,180] |

| BDQ: pediatric-leaning nanoemulsions | DoE-guided vegetable-oil nanoemulsion | Preclinical formulation work with in vitro release and stability | Droplets near 190 to 200 nm with controlled release and scalable processing | Supports child-friendly oral BDQ formats | [157] |

| BDQ: long-acting depot | Long-acting injectable suspension | Validated mouse preventive-therapy model | Single dose near 160 mg/kg protected for about 12 weeks | Depot delivery extends exposure and reduces dosing burden | [181] |

| Rifabutin: ISFI | PLGA-based in situ forming implant | Mouse prevention and treatment models | Sustained rifabutin for about 16 weeks and cleared infection | Quarterly style option for rifamycins | [149] |

| CFZ: inhalable powder | DoE-optimized PLGA microparticles | In vitro work with M. tuberculosis H37Ra and aerosol testing | Particles near 1 μm with high entrapment and biphasic release; eight-fold higher activity | Suited for alveolar macrophage targeting | [133] |

| CFZ: oral loading | Once-daily 300 mg for four weeks | Clinical PK setting | Faster attainment of CFZ target concentrations | Alternative when inhalation not feasible | [159] |

| Rifampicin: liposomes for the lung | Nebulized liposomes and microparticle blends | Guinea pig pulmonary TB model | Lower lung CFU and smaller spleen weights | Evidence for pulmonary translation | [161] |

| Rifampicin: inhaled powders | Aerosolized dry powders | Mouse and guinea pig PK/PD studies | Higher bioavailability and lung exposure at lower doses than oral dosing | Device and route can outperform oral dosing | [25] |

| Nanocarriers: design rules | Macrophage-targeted polymeric and lipid carriers with responsive release | Synthesis of nanocarrier evidence | Carriers between about 100 and 200 nm with tuned charge and contextual responsiveness raised intralesional levels | Lesion PK/PD predicts cure better than plasma; engineered carriers outperform free drug | [28] |

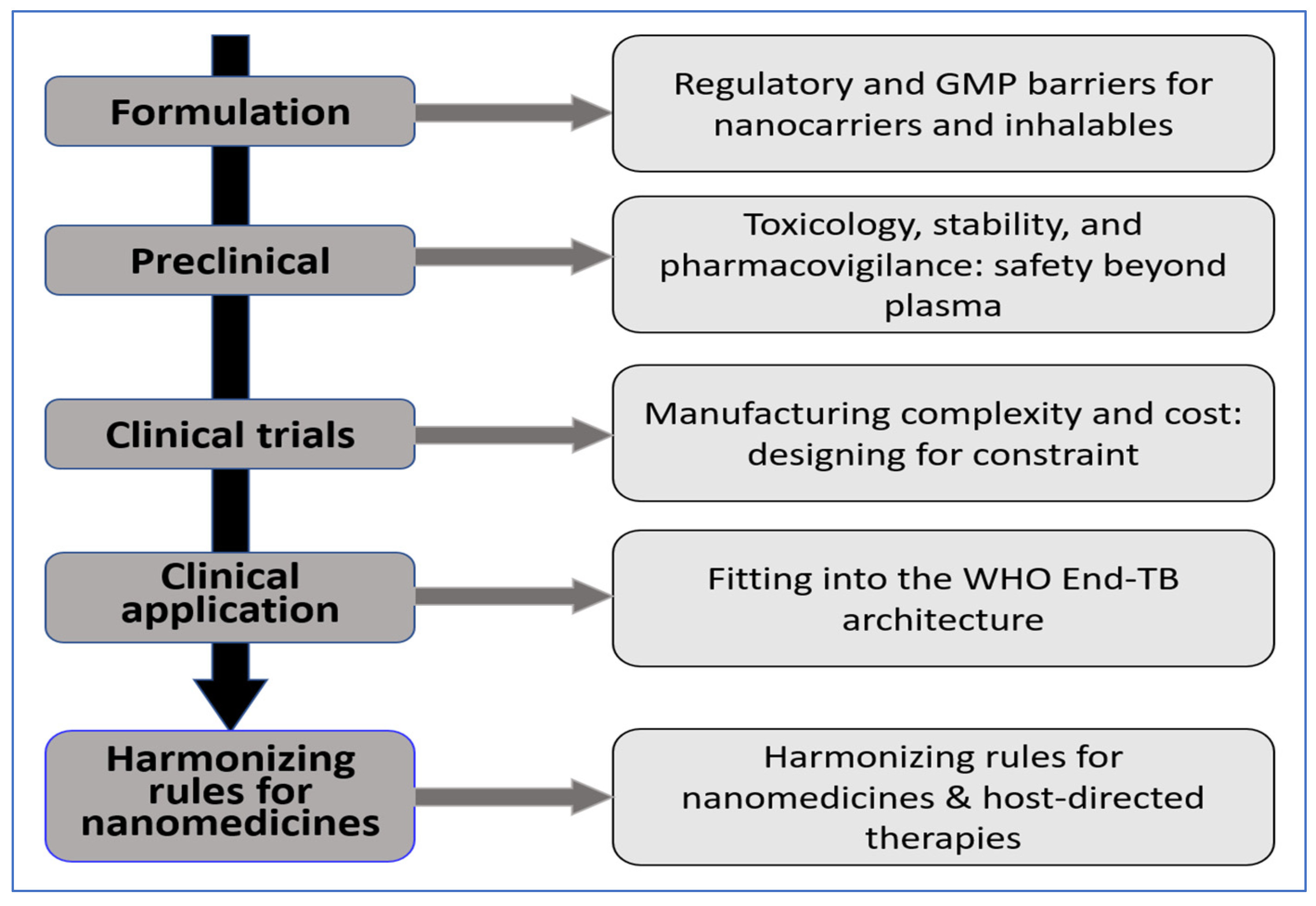

6. Translational and Regulatory Challenges

6.1. Regulatory and Gmp Hurdles for Nanocarriers and Inhalables

6.2. Toxicology, Stability, and Pharmacovigilance: Safety Beyond Plasma

6.3. Manufacturing Complexity and Cost: Designing for Constraint

6.4. Integration Within the WHO End TB Strategy Framework

6.5. Harmonizing Rules for Nanomedicines and HDTs

6.6. What a Workable Path Looks Like

7. Future Perspectives and Outlook

7.1. Smarter Design and Selection

7.2. Delivery in Real Lungs

7.3. Choosing Regimens and Doses Sooner

7.4. Vaccines, Gene-Based Adjuncts, and Manufacturability

7.5. A Near-Term Blueprint We Can Act on Now

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Yang, H.; Ruan, X.; Li, W.; Xiong, J.; Zheng, Y. Global, regional, and national burden of tuberculosis and attributable risk factors for 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases 2021 study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Cotugno, S.; Guido, G.; Cavallin, F.; Pisaturo, M.; Onorato, L.; Zimmerhofer, F.; Pipitò, L.; De Iaco, G.; Bruno, G. Disparities in tuberculosis diagnostic delays between native and migrant populations in Italy: A multicenter study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 150, 107279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Tuberculosis Resurges as Top Infectious Disease Killer; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/1-11-2024-tuberculosis-resurges-top-infectious-disease-killer? (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis: Module 4—Treatment: Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240048126? (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). TB Knowledge Sharing Platform—Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis; Section 3.4; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://tbksp.who.int/es/node/2774? (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Dorman, S.E.; Nahid, P.; Kurbatova, E.V.; Phillips, P.P.; Bryant, K.; Dooley, K.E.; Engle, M.; Goldberg, S.V.; Phan, H.T.; Hakim, J. Four-month rifapentine regimens with or without moxifloxacin for tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1705–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, W. Interim guidance: 4-month rifapentine-moxifloxacin regimen for the treatment of drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarathy, J.P.; Zuccotto, F.; Hsinpin, H.; Sandberg, L.; Via, L.E.; Marriner, G.A.; Masquelin, T.; Wyatt, P.; Ray, P.; Dartois, V. Prediction of drug penetration in tuberculosis lesions. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016, 2, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.M.; Mills, D.; Spraggins, J.; Lambert, W.S.; Calkins, D.J.; Schey, K.L. High-resolution matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–imaging mass spectrometry of lipids in rodent optic nerve tissue. Mol. Vis. 2013, 19, 581. [Google Scholar]

- Lenaerts, A.; Barry, C.E., III; Dartois, V. Heterogeneity in tuberculosis pathology, microenvironments and therapeutic responses. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 264, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, L.; Daudelin, I.B.; Podell, B.K.; Chen, P.-Y.; Zimmerman, M.; Martinot, A.J.; Savic, R.M.; Prideaux, B.; Dartois, V. High-resolution mapping of fluoroquinolones in TB rabbit lesions reveals specific distribution in immune cell types. eLife 2018, 7, e41115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilma, A.; Bailey, H.; Karakousis, P.C.; Karanika, S. HIV/tuberculosis coinfection in pregnancy and the postpartum period. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarathy, J.P.; Dartois, V. Caseum: A niche for Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug-tolerant persisters. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00159-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, N.; Gupta, S.V.; Fox, W.S.; Via, L.E.; Bang, H.; Lee, M.; Eum, S.; Shim, T.; Barry, C.E., III; Zimmerman, M. Tuberculosis drugs’ distribution and emergence of resistance in patient’s lung lesions: A mechanistic model and tool for regimen and dose optimization. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crofton, J. The MRC randomized trial of streptomycin and its legacy: A view from the clinical front line. J. R. Soc. Med. 2006, 99, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerantzas, C.A.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr. Origins of combination therapy for tuberculosis: Lessons for future antimicrobial development and application. mBio 2017, 8, e01586-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.F.; Schraufnagel, D.E.; Hopewell, P.C. Treatment of tuberculosis. A historical perspective. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, 1749–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, V.N.; Wetzstein, N. Building on the past: Revisiting historical tuberculosis trials in a modern era. CMI Commun. 2025, 2, 105132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensi, P. History of the development of rifampin. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1983, 5, S402–S406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudzinová, P.; Šanderová, H.; Koval’, T.; Skálová, T.; Borah, N.; Hnilicová, J.; Kouba, T.; Dohnálek, J.; Krásný, L. What the Hel: Recent advances in understanding rifampicin resistance in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuac051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). SIRTURO (Bedaquiline) Tablets—NDA Approval Letter; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2012/204384Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Deltyba, INN—Delamanid: Product Information (EPAR); European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/deltyba-epar-product-information_en.pdf? (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Pretomanid Tablets—NDA 212862 Approval Package; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212862Orig1s000Approv.pdf? (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Khadka, P.; Dummer, J.; Hill, P.C.; Katare, R.; Das, S.C. A review of formulations and preclinical studies of inhaled rifampicin for its clinical translation. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2023, 13, 1246–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainwal, N.; Sharma, Y.; Jakhmola, V. Dry powder inhalers of antitubercular drugs. Tuberculosis 2022, 135, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buya, A.B.; Witika, B.A.; Bapolisi, A.M.; Mwila, C.; Mukubwa, G.K.; Memvanga, P.B.; Makoni, P.A.; Nkanga, C.I. Application of lipid-based nanocarriers for antitubercular drug delivery: A review. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Virmani, T.; Kumar, G.; Deshmukh, R.; Sharma, A.; Duarte, S.; Brandão, P.; Fonte, P. Nanocarriers in tuberculosis treatment: Challenges and delivery strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aekwattanaphol, N.; Das, S.C.; Khadka, P.; Nakpheng, T.; Bintang, M.A.K.M.; Srichana, T. Development of a proliposomal pretomanid dry powder inhaler as a novel alternative approach for combating pulmonary tuberculosis. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 664, 124608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.M.; Diorio, A.M.; Kommarajula, P.; Kunda, N.K. A quality-by-design strategic approach for the development of bedaquiline-pretomanid nanoparticles as inhalable dry powders for TB treatment. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 653, 123920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, H.; Zhao, C.; Tian, X.; Cun, D.; Yang, M. Mannose-decorated solid-lipid nanoparticles for alveolar macrophage targeted delivery of rifampicin. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Xia, J.; Yu, J.; Chen, D.; Huang, Y.; Yang, F.; Ruan, Y.; Xu, J.-F. Nanomaterial-mediated host directed therapy of tuberculosis by manipulating macrophage autophagy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Chu, H.; Li, Q.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J.; Chu, N.; Sun, Z. Host-directed therapy for tuberculosis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammerman, N.C.; Nuermberger, E.L.; Owen, A.; Rannard, S.P.; Meyers, C.F.; Swindells, S. Potential impact of long-acting products on the control of tuberculosis: Preclinical advancements and translational tools in preventive treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, S510–S516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longest, P.W.; Bass, K.; Dutta, R.; Rani, V.; Thomas, M.L.; El-Achwah, A.; Hindle, M. Use of computational fluid dynamics deposition modeling in respiratory drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadafi, H.; Monshi Tousi, N.; De Backer, W.; De Backer, J. Validation of computational fluid dynamics models for airway deposition with SPECT data of the same population. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long-Acting/Extended Release Antiretroviral Resource Program (LEAP). Long-Acting Tuberculosis Drug Development Workshop 2024; LEAP: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://longactinghiv.org/LEAP-TB-WORKSHOP-2024? (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Vermeulen, M.; Scarsi, K.; Furl, R.; Sayles, H.; Anderson, M.; Valawalkar, S.; Kadam, A.; Cox, S.; Mave, V.; Barthwal, M. Patient and provider preferences for long-acting TB preventive therapy. IJTLD Open 2025, 2, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, D.; Li, X.; Wei, J.; Du, W.; Zhao, A.; Xu, M. RNA vaccines: The dawn of a new age for tuberculosis? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2469333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Rhee, K.Y. Tuberculosis drug development: History and evolution of the mechanism-based paradigm. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a021147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Soni, A.; Tanwar, O.; Bhadane, R.; Besra, G.S.; Kawathekar, N. DprE1 inhibitors: Enduring aspirations for future antituberculosis drug discovery. ChemMedChem 2023, 18, e202300099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, E.J.; Schwartz, C.P.; Zgurskaya, H.I.; Jackson, M. Recent advances in mycobacterial membrane protein large 3 inhibitor drug design for mycobacterial infections. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2023, 18, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoelscher, M.; Barros-Aguirre, D.; Dara, M.; Heinrich, N.; Sun, E.; Lange, C.; Tiberi, S.; Wells, C. Candidate anti-tuberculosis medicines and regimens under clinical evaluation. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufa, M.; Finger, V.; Kovar, O.; Soukup, O.; Torruellas, C.; Roh, J.; Korabecny, J. Revolutionizing tuberculosis treatment: Breakthroughs, challenges, and hope on the horizon. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 1311–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, R.; Diacon, A.H.; Takuva, S.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Karwe, V.; Hafkin, J. Quabodepistat in combination with delamanid and bedaquiline in participants with drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis: Protocol for a multicenter, phase 2b/c, open-label, randomized, dose-finding trial to evaluate safety and efficacy. Trials 2024, 25, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, N.; de Jager, V.; Dreisbach, J.; Gross-Demel, P.; Schultz, S.; Gerbach, S.; Kloss, F.; Dawson, R.; Narunsky, K.; Matt, L. Safety, bactericidal activity, and pharmacokinetics of the antituberculosis drug candidate BTZ-043 in South Africa (PanACEA-BTZ-043–02): An open-label, dose-expansion, randomised, controlled, phase 1b/2a trial. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacon, A.H.; Barry, C.E., III; Carlton, A.; Chen, R.Y.; Davies, M.; de Jager, V.; Fletcher, K.; Koh, G.C.; Kontsevaya, I.; Heyckendorf, J. A first-in-class leucyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor, ganfeborole, for rifampicin-susceptible tuberculosis: A phase 2a open-label, randomized trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-Y.; Tyagi, S.; Soni, H.; Betoudji, F.; Converse, P.J.; Mdluli, K.; Upton, A.M.; Fotouhi, N.; Barros-Aguirre, D.; Ballell, L. Bactericidal and sterilizing activity of novel regimens combining bedaquiline or TBAJ-587 with GSK2556286 and TBA-7371 in a mouse model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e01562-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis: Module 4—Treatment: Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment (2022 Update); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063129? (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Nimmo, C.; Bionghi, N.; Cummings, M.J.; Perumal, R.; Hopson, M.; Al Jubaer, S.; Naidoo, K.; Wolf, A.; Mathema, B.; Larsen, M.H. Opportunities and limitations of genomics for diagnosing bedaquiline-resistant tuberculosis: A systematic review and individual isolate meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, e164–e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, R.; Bionghi, N.; Nimmo, C.; Letsoalo, M.; Cummings, M.J.; Hopson, M.; Wolf, A.; Al Jubaer, S.; Padayatchi, N.; Naidoo, K. Baseline and treatment-emergent bedaquiline resistance in drug-resistant tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 62, 2300639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snobre, J.; Meehan, C.; Mulders, W.; Rigouts, L.; Buyl, R.; de Jong, B.; Van Rie, A.; Tzfadia, O. Frameshift mutations in the mmpR5 gene can have a bedaquiline-susceptible phenotype by retaining a protein structure and function similar to wild-type Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e00854-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babii, S.; Li, W.; Yang, L.; Grzegorzewicz, A.E.; Jackson, M.; Gumbart, J.C.; Zgurskaya, H.I. Allosteric coupling of substrate binding and proton translocation in MmpL3 transporter from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. mBio 2024, 15, e02183-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Section 1.3: Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. In Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024/tb-disease-burden/1-3-drug-resistant-tb (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Shi, J.; Li, L.; Wu, T.; Chu, P.; Pang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Gao, M.; Lu, J. Spontaneous mutational patterns and novel mutations for delamanid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e00531-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichmuth, M.L.; Hömke, R.; Zürcher, K.; Sander, P.; Avihingsanon, A.; Collantes, J.; Loiseau, C.; Borrell, S.; Reinhard, M.; Wilkinson, R.J. Natural polymorphisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis conferring resistance to delamanid in drug-naive patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00513-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.; Yang, W.; Ou, X.; Zhao, B.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhuang, J.; Li, C. High-Level Primary Pretomanid-Resistant with ddn In-Frame Deletion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Its Association with Lineage 4.5 in China. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 26551–26559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, F.; Bagdasaryan, T.R.; Borisov, S.; Howell, P.; Mikiashvili, L.; Ngubane, N.; Samoilova, A.; Skornykova, S.; Tudor, E.; Variava, E. Bedaquiline–pretomanid–linezolid regimens for drug-resistant tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conradie, F.; Diacon, A.H.; Ngubane, N.; Howell, P.; Everitt, D.; Crook, A.M.; Mendel, C.M.; Egizi, E.; Moreira, J.; Timm, J. Treatment of highly drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, R.; Diacon, A.H.; De Jager, V.; Narunsky, K.; Moodley, V.M.; Stinson, K.W.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Hafkin, J. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and early bactericidal activity of quabodepistat in combination with delamanid, bedaquiline, or both in adults with pulmonary tuberculosis: A randomised, active-controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, D.; de Jager, V.; Dawson, R.; Narunsky, K.; Moloantoa, T.; Venter, E.; Stinson, K.; Levi, M.; Anderson, A.; Grekas, E.; et al. A randomized, active-control, open-label Phase 2a trial evaluating the bactericidal activity, safety, and pharmacokinetics of TBA-7371 in drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Lung Health 2023, Paris, France, 15–18 November 2023; Presentation. Bill & Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.gatesmri.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/tbd03-201-union-late-breaker-abstract.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Heinrich, N.; Manyama, C.; Koele, S.E.; Mpagama, S.; Mhimbira, F.; Sebe, M.; Wallis, R.S.; Ntinginya, N.; Liyoyo, A.; Huglin, B. Sutezolid in combination with bedaquiline, delamanid, and moxifloxacin for pulmonary tuberculosis (PanACEA-SUDOCU-01): A prospective, open-label, randomised, phase 2b dose-finding trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, S.; Upton, C.; de Jager, V.R.; van Niekerk, C.; Dawson, R.; Hutchings, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.; Nam, K.; Sun, E. Telacebec, a Potent Agent in the Fight Against Tuberculosis: Findings from A Randomized, Phase 2 Clinical Trial and Beyond. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phase 2a Study to Evaluate the Early Bactericidal Activity, Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Multiple Oral Doses of Telacebec (Q203). New TB Drugs. 2022. Available online: https://www.newtbdrugs.org/pipeline/trials/phase-2-telacebec-q203-eba? (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Hartkoorn, R.C.; Uplekar, S.; Cole, S.T. Cross-resistance between clofazimine and bedaquiline through upregulation of MmpL5 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2979–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsaman, T.; Mohamed, M.S.; Mohamed, M.A. Current development of 5-nitrofuran-2-yl derivatives as antitubercular agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 88, 102969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuma, N.H.; Smit, F.J.; Seldon, R.; Aucamp, J.; Jordaan, A.; Warner, D.F.; N’Da, D.D. Single-step synthesis and in vitro anti-mycobacterial activity of novel nitrofurantoin analogues. Bioorg Chem. 2020, 96, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh; Bruhn, D.F.; Scherman, M.S.; Woolhiser, L.K.; Madhura, D.B.; Maddox, M.M.; Singh, A.P.; Lee, R.B.; Hurdle, J.G.; McNeil, M.R. Pentacyclic nitrofurans with in vivo efficacy and activity against nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarova, K.; Vinogradova, L.; Lukin, A.; Zhuravlev, M.; Deniskin, D.; Chudinov, M.; Gureev, M.; Dogonadze, M.; Zabolotnykh, N.; Vinogradova, T. The Nitrofuran-Warhead-Equipped Spirocyclic Azetidines Show Excellent Activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecules 2024, 29, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koele, S.E.; Heinrich, N.; De Jager, V.R.; Dreisbach, J.; Phillips, P.P.; Gross-Demel, P.; Dawson, R.; Narunsky, K.; Wildner, L.M.; Mchugh, T.D. Population pharmacokinetics and exposure–response relationship of the antituberculosis drug BTZ-043. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbelowo, O.; Sarathy, J.P.; Gausi, K.; Zimmerman, M.D.; Wang, H.; Wijnant, G.-J.; Kaya, F.; Gengenbacher, M.; Van, N.; Degefu, Y. Pharmacokinetics and target attainment of SQ109 in plasma and human-like tuberculosis lesions in rabbits. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e00024-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, J.; Paradis, N.J.; Bennet, L.; Alesiani, M.C.; Hausman, K.R.; Wu, C. Inhibition mechanism of anti-TB drug SQ109: Allosteric inhibition of TMM translocation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis MmpL3 transporter. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 5356–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jager, V.R.; Dawson, R.; van Niekerk, C.; Hutchings, J.; Kim, J.; Vanker, N.; van der Merwe, L.; Choi, J.; Nam, K.; Diacon, A.H. Telacebec (Q203), a new antituberculosis agent. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1280–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, J.; Kang, H.; Ahn, J.; Hutchings, J.; Niekerk, C.v.; Kim, J.; Jeon, Y.; Nam, K.; Kim, T.H. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and metabolism of Telacebec (Q203) for the treatment of tuberculosis: A randomized, placebo-controlled, multiple ascending dose phase 1B trial. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e01123-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauffour, A.; Cambau, E.; Pethe, K.; Veziris, N.; Aubry, A. Unprecedented in vivo activity of telacebec against Mycobacterium leprae. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0013076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, I.; Boeree, M.; Chesov, D.; Dheda, K.; Günther, G.; Horsburgh, C.R., Jr.; Kherabi, Y.; Lange, C.; Lienhardt, C.; McIlleron, H.M. Recent advances in the treatment of tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.H.; Burke, A.; Cho, J.-G.; Alffenaar, J.-W.; Davies Forsman, L. New oxazolidinones for tuberculosis: Are novel treatments on the horizon? Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, O.; Dikeman, D.A.; Ortines, R.V.; Wang, Y.; Youn, C.; Mumtaz, M.; Orlando, N.; Zhang, J.; Patel, A.M.; Gough, E. The novel oxazolidinone TBI-223 is effective in three preclinical mouse models of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02451-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, N.; Ernest, J.P.; Imperial, M.; Solans, B.P.; Wang, Q.; Tasneen, R.; Tyagi, S.; Soni, H.; Garcia, A.; Bigelow, K. Dose optimization of TBI-223 for enhanced therapeutic benefit compared to linezolid in antituberculosis regimen. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, A.; Pappas, F.; Bruinenberg, P.; Nedelman, J.; Taneja, R.; Hickman, D.; Beumont, M.; Sun, E. Pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and safety of TBI-223, a novel oxazolidinone, in healthy participants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e01542-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspard, M.; Butel, N.; El Helali, N.; Marigot-Outtandy, D.; Guillot, H.; Peytavin, G.; Veziris, N.; Bodaghi, B.; Flandre, P.; Petitjean, G. Linezolid-associated neurologic adverse events in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.-G.; Liu, X.-M.; Wu, S.-Q.; He, J.-Q. Impacts of clofazimine on the treatment outcomes of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 2023, 25, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal, M.; Padayatchi, N.; Metcalfe, J.; O’Donnell, M. Systematic review of clofazimine for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2013, 17, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.P.; Peloquin, C.A.; Sterling, T.R.; Kaur, P.; Diacon, A.H.; Gotuzzo, E.; Benator, D.; Warren, R.M.; Sikes, D.; Lecca, L. Efficacy and safety of higher doses of levofloxacin for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: A randomized, placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- England, K.; Boshoff, H.I.; Arora, K.; Weiner, D.; Dayao, E.; Schimel, D.; Via, L.E.; Barry, C.E., III. Meropenem-clavulanic acid shows activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3384–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberi, S.; Sotgiu, G.; D’Ambrosio, L.; Centis, R.; Arbex, M.A.; Arrascue, E.A.; Alffenaar, J.W.; Caminero, J.A.; Gaga, M.; Gualano, G. Comparison of effectiveness and safety of imipenem/clavulanate-versus meropenem/clavulanate-containing regimens in the treatment of MDR-and XDR-TB. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 1758–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degner, N.R.; Wang, J.-Y.; Golub, J.E.; Karakousis, P.C. Metformin use reverses the increased mortality associated with diabetes mellitus during tuberculosis treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.; Jeong, D.; Mok, J.; Jeon, D.; Kang, H.-Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Choi, H.; Kang, Y.A. Relationship between metformin use and mortality in tuberculosis patients with diabetes: A nationwide cohort study. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetteh, P.; Danso, E.K.; Osei-Wusu, S.; Yeboah-Manu, D.; Asare, P. The role of metformin in tuberculosis control among TB and diabetes mellitus comorbid individuals. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1549572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, S.P.; Guler, R.; Khutlang, R.; Lang, D.M.; Hurdayal, R.; Mhlanga, M.M.; Suzuki, H.; Marais, A.D.; Brombacher, F. Statin therapy reduces the mycobacterium tuberculosis burden in human macrophages and in mice by enhancing autophagy and phagosome maturation. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, K.-M.; Lee, C.-S.; Wu, Y.-C.; Shu, C.-C.; Ho, C.-H. Association between statin use and tuberculosis risk in patients with bronchiectasis: A retrospective population-based cohort study in Taiwan. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2024, 11, e002077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeel, S.; Motaung, B.; Ozturk, M.; Mafu, T.S.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Thienemann, F.; Guler, R. Immunomodulatory effects of atorvastatin on peripheral blood mononuclear cells infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1597534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.-x.; Xiong, X.-f.; Zhu, M.; Wei, J.; Zhuo, K.-q.; Cheng, D.-y. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on the outcomes of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2018, 18, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lin, T.; Pan, Y. Vitamin D supplementation for tuberculosis prevention: A meta-analysis. Biomol. Biomed. 2025, 26, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, A.-M.; Andersson, B.; Lorell, C.; Raffetseder, J.; Larsson, M.; Blomgran, R. Autophagy induction targeting mTORC1 enhances Mycobacterium tuberculosis replication in HIV co-infected human macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo, B.I.; Khan, A.; Singh, V.K.; de-Leon, E.; Aguillón-Durán, G.P.; Ledezma-Campos, E.; Canaday, D.H.; Jagannath, C. Human monocyte-derived macrophage responses to M. tuberculosis differ by the host’s tuberculosis, diabetes or obesity status, and are enhanced by rapamycin. Tuberculosis 2021, 126, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liang, R.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Hu, Q.; Wen, Q.; Zhao, H. Pharmacokinetics of Nitazoxanide Dry Suspensions After Single Oral Doses in Healthy Subjects: Food Effects Evaluation and Bioequivalence Study. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2024, 13, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilinç, G.; Boland, R.; Heemskerk, M.T.; Spaink, H.P.; Haks, M.C.; van der Vaart, M.; Ottenhoff, T.H.; Meijer, A.H.; Saris, A. Host-directed therapy with amiodarone in preclinical models restricts mycobacterial infection and enhances autophagy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00167-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, N.; Sigal, A.; Naidoo, K. Metformin as host-directed therapy for TB treatment: Scoping review. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, J.; Yang, E.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Xia, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, L. Macrophage targeted graphene oxide nanosystem synergize antibiotic killing and host immune defense for Tuberculosis Therapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 208, 107379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Santiago, B.; Hernandez-Pando, R.; Carranza, C.; Juarez, E.; Contreras, J.L.; Aguilar-Leon, D.; Torres, M.; Sada, E. Expression of cathelicidin LL-37 during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in human alveolar macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, and epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rekha, R.S.; Rao Muvva, S.J.; Wan, M.; Raqib, R.; Bergman, P.; Brighenti, S.; Gudmundsson, G.H.; Agerberth, B. Phenylbutyrate induces LL-37-dependent autophagy and intracellular killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1688–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Does, A.M.; Beekhuizen, H.; Ravensbergen, B.; Vos, T.; Ottenhoff, T.H.; van Dissel, J.T.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Hiemstra, P.S.; Nibbering, P.H. LL-37 directs macrophage differentiation toward macrophages with a proinflammatory signature. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, A.; Talukdar, S.; Chaubey, G.K.; Dilawari, R.; Modanwal, R.; Chaudhary, S.; Patidar, A.; Boradia, V.M.; Kumbhar, P.; Raje, C.I. Regulation of macrophage cell surface GAPDH alters LL-37 internalization and downstream effects in the cell. J. Innate Immun. 2023, 15, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnananthasivam, S.; Li, H.; Bouzeyen, R.; Shunmuganathan, B.; Purushotorman, K.; Liao, X.; Du, F.; Friis, C.G.K.; Crawshay-Williams, F.; Boon, L.H. An anti-LpqH human monoclonal antibody from an asymptomatic individual mediates protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Labani-Motlagh, A.; Bohorquez, J.A.; Moreira, J.D.; Ansari, D.; Patel, S.; Spagnolo, F.; Florence, J.; Vankayalapati, A.; Sakai, T. Bacteriophage therapy for the treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections in humanized mice. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfull, G.F. Phage therapy for nontuberculous mycobacteria: Challenges and opportunities. Pulm. Ther. 2023, 9, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nick, J.A.; Dedrick, R.M.; Gray, A.L.; Vladar, E.K.; Smith, B.E.; Freeman, K.G.; Malcolm, K.C.; Epperson, L.E.; Hasan, N.A.; Hendrix, J. Host and pathogen response to bacteriophage engineered against Mycobacterium abscessus lung infection. Cell 2022, 185, 1860–1874.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Gangakhedkar, R.; Thakur, H.S.; Raman, S.K.; Patil, S.A.; Jain, V. Mycobacteriophage D29 Lysin B exhibits promising anti-mycobacterial activity against drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04597-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jowsey, W.J.; Cheung, C.-Y.; Smart, C.J.; Klaus, H.R.; Seeto, N.E.; Waller, N.J.; Chrisp, M.T.; Peterson, A.L.; Ofori-Anyinam, B. Whole genome CRISPRi screening identifies druggable vulnerabilities in an isoniazid resistant strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, J.; Li, S.; Li, C.; Pang, Y. Development and clinical evaluation of a CRISPR/Cas13a-based diagnostic test to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical specimens. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1117085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, N.; Pang, M.; Miao, H.; Dai, X.; Li, B.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Liu, Y. Rapid and Highly Sensitive Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Utilizing the Recombinase Aided Amplification-Based CRISPR-Cas13a System. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakku, S.G.; Lirette, J.; Murugesan, K.; Chen, J.; Theron, G.; Banaei, N.; Blainey, P.C.; Gomez, J.; Wong, S.Y.; Hung, D.T. Genome-wide tiled detection of circulating Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell-free DNA using Cas13. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeman, H.; Al-Wassiti, H.; Fabb, S.A.; Lim, L.; Wang, T.; Britton, W.J.; Steain, M.; Pouton, C.W.; Triccas, J.A.; Counoupas, C. A lipid nanoparticle-mRNA vaccine provides potent immunogenicity and protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeman, H.; Al-Wassiti, H.; Fabb, S.A.; Lim, L.; Wang, T.; Britton, W.J.; Steain, M.; Pouton, C.W.; Triccas, J.A.; Counoupas, C. An LNP-mRNA vaccine modulates innate cell trafficking and promotes polyfunctional Th1 CD4+ T cell responses to enhance BCG-induced protective immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. eBioMedicine 2025, 113, 105599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shi, M.; Wang, Y.; You, J. Progress and prospects of mRNA-based drugs in pre-clinical and clinical applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opperman, C.J.; Brink, A.J. Phage Therapy for Mycobacteria: Overcoming Challenges, Unleashing Potential. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, H.; Padmapriyadarsini, C.; Chuchottaworn, C.; Foraida, S.; Hadigal, S.; Birajdar, A. Efficacy and safety data on pretomanid for drug-resistant TB. IJTLD Open 2025, 2, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römpp, A.; Treu, A.; Kokesch-Himmelreich, J.; Marwitz, F.; Dreisbach, J.; Aboutara, N.; Hillemann, D.; Garrelts, M.; Converse, P.J.; Tyagi, S. The clinical-stage drug BTZ-043 accumulates in murine tuberculosis lesions and efficiently acts against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vocat, A.; Luraschi-Eggemann, A.; Antoni, C.; Cathomen, G.; Cichocka, D.; Greub, G.; Riabova, O.; Makarov, V.; Opota, O.; Mendoza, A. Real-time evaluation of macozinone activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis through bacterial nanomotion analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e01318-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, K.; Te Brake, L.H.; Lemm, A.-K.; Hoelscher, M.; Svensson, E.M.; Hölscher, C.; Heinrich, N. Investigating the treatment shortening potential of a combination of bedaquiline, delamanid and moxifloxacin with and without sutezolid, in a murine tuberculosis model with confirmed drug exposures. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 2607–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L.J.; Velásquez, G.E.; Kempker, R.R.; Imperial, M.Z.; Nuermberger, E.; Dorman, S.E.; Ignatius, E.; Granche, J.; Phillips, P.P.; Furin, J. ACTG A5409 (RAD-TB): Study protocol for a phase 2 randomized, adaptive, dose-ranging, open-label trial of novel regimens for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Trials 2025, 26, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmetti, L.; Khan, U.; Velásquez, G.E.; Gouillou, M.; Ali, M.H.; Amjad, S.; Kamal, F.; Abubakirov, A.; Ardizzoni, E.; Baudin, E. Bedaquiline, delamanid, linezolid, and clofazimine for rifampicin-resistant and fluoroquinolone-resistant tuberculosis (endTB-Q): An open-label, multicentre, stratified, non-inferiority, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2025, 13, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.; Medcalf, E.; Nyang’wa, B.-T.; Egizi, E.; Berry, C.; Dodd, M.; Foraida, S.; Gegia, M.; Li, M.; Mirzayev, F. The safety and tolerability of linezolid in novel short-course regimens containing bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid to treat rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 78, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davuluri, K.S.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, A.V.; Chaudhary, P.; Raman, S.K.; Kushwaha, S.; Singh, S.V.; Chauhan, D.S. Atorvastatin potentially reduces mycobacterial severity through its action on lipoarabinomannan and drug permeability in granulomas. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03197-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.; Li, X.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, P.; Gao, S. The role of vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Infection 2025, 53, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, D.; Nilsson, B.-O. Human antimicrobial/host defense peptide LL-37 may prevent the spread of a local infection through multiple mechanisms: An update. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 74, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, A.G.; Dunkley, O.R.; Modi, N.H.; Huang, Y.; Tseng, S.; Reiss, R.; Daivaa, N.; Davis, J.L.; Vargas, D.A.; Banada, P. A streamlined CRISPR-based test for tuberculosis detection directly from sputum. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadx2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, W.; Ahmad, S.; Rahman, M.U.; Akram, H.; Abdullah, U. Nanostructured lipid carriers applications in cosmeceuticals: Structure, formulation, safety profile and market trends. Prospect. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 23, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singireddy, A.R.; Pedireddi, S.R. Advances in lopinavir formulations: Strategies to overcome solubility, bioavailability, and stability challenges. Prospect. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 22, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Prakash, P.; Mohtar, N.; Kumar, K.S.; Parumasivam, T. Review of inhalable nanoparticles for the pulmonary delivery of anti-tuberculosis drugs. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2023, 28, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Grainger, D.W. Regulatory considerations specific to liposome drug development as complex drug products. Front. Drug Deliv. 2022, 2, 901281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongala, D.S.; Patil, S.M.; Kunda, N.K. Design of experiment (DoE) approach for developing inhalable PLGA microparticles loaded with clofazimine for tuberculosis treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdopórpora, J.M.; Martinena, C.; Bernabeu, E.; Riedel, J.; Palmas, L.; Castangia, I.; Manca, M.L.; Garcés, M.; Lázaro-Martinez, J.; Salgueiro, M.J. Inhalable mannosylated rifampicin–curcumin co-loaded nanomicelles with enhanced in vitro antimicrobial efficacy for an optimized pulmonary tuberculosis therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Greeny, A.; Nandan, A.; Sah, R.K.; Jose, A.; Dyawanapelly, S.; Junnuthula, V.; KV, A.; Sadanandan, P. Advanced drug delivery and therapeutic strategies for tuberculosis treatment. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashyal, S.; Suwal, N.; Thapa, R.; Bagale, L.R.; Sugandhi, V.; Subedi, S.; Idrees, S.; Panth, N.; Elwakil, B.H.; El-Khatib, M. Liposomal drug delivery system for lung diseases: Recent advancement and future perspectives. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2025, 69, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, W.-R.; Chang, R.Y.K.; Kwok, P.C.L.; Tang, P.; Chen, L.; Chen, D.; Chan, H.-K. Administration of dry powders during respiratory supports. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Gao, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, L.; Xiao, Y. Current development of nano-drug delivery to target macrophages. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque-Borda, C.A.; Vishwakarma, S.K.; Delgado, O.J.R.; de Souza Rodrigues, H.L.; Primo, L.M.; Campos, I.C.; De Lima, T.S.; Perdigão, J.; Pavan, F.R. Peptide-Based Strategies Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Covering Immunomodulation, Vaccines, Synergistic Therapy, and Nanodelivery. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, R.; Popli, P.; Sal, K.; Challa, R.R.; Vallamkonda, B.; Garg, M.; Dora, C.P. A review on biomacromolecular ligand-directed nanoparticles: New era in macrophage targeting. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, T.O.; Poka, M.S.; Witika, B.A. Nanotechnological innovations in paediatric tuberculosis management: Current trends and future prospects. Front. Drug Deliv. 2024, 3, 1295815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Drug Products, Including Biological Products, That Contain Nanomaterials—Guidance for Industry; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/157812/download? (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Das, S.S.; Bharadwaj, P.; Bilal, M.; Barani, M.; Rahdar, A.; Taboada, P.; Bungau, S.; Kyzas, G.Z. Stimuli-responsive polymeric nanocarriers for drug delivery, imaging, and theragnosis. Polymers 2020, 12, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, N. Stimuli-responsive nanoparticles for lung disorder treatment: From serendipity to precision phosphorylation modulation and drug repurposing. Next Nanotechnol. 2025, 7, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, F.; Liu, M. New opportunities of stimulus-responsive smart nanocarriers in cancer therapy. Nano Mater. Sci. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarathy, J.P.; Via, L.E.; Weiner, D.; Blanc, L.; Boshoff, H.; Eugenin, E.A.; Barry, C.E., III; Dartois, V.A. Extreme drug tolerance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in caseum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02266-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lin, N.; Hu, J.; Zhang, B. Stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems for the diagnosis and therapy of lung cancer. Molecules 2022, 27, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naureen, F.; Shah, Y.; Rehman, M.u.; Chaubey, P.; Nair, A.K.; Khan, J.; Abdullah; Shafique, M.; Shah, K.U.; Ahmad, B. Inhalable dry powder nano-formulations: Advancing lung disease therapy-a review. Front. Nanotechnol. 2024, 6, 1403313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Johnson, C.E.; Schmalstig, A.A.; Annis, A.; Wessel, S.E.; Van Horn, B.; Schauer, A.; Exner, A.A.; Stout, J.E.; Wahl, A. A long-acting formulation of rifabutin is effective for prevention and treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Li, S.-Y.; Pertinez, H.; Betoudji, F.; Lee, J.; Rannard, S.P.; Owen, A.; Nuermberger, E.L.; Ammerman, N.C. Using dynamic oral dosing of rifapentine and rifabutin to simulate exposure profiles of long-acting formulations in a mouse model of tuberculosis preventive therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e00481-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nande, A.; Hill, A.L. The risk of drug resistance during long-acting antimicrobial therapy. Proc. R. Soc. B 2022, 289, 20221444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenelle, D.C.; Staas, J.K.; Winchester, G.A.; Barrow, E.L.; Barrow, W.W. Efficacy of microencapsulated rifampin in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Jahagirdar, P.; Tripathi, D.; Devarajan, P.V.; Kulkarni, S. Macrophage targeted polymeric curcumin nanoparticles limit intracellular survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through induction of autophagy and augment anti-TB activity of isoniazid in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1233630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekale, R.B.; Maphasa, R.E.; D’Souza, S.; Hsu, N.J.; Walters, A.; Okugbeni, N.; Kinnear, C.; Jacobs, M.; Sampson, S.L.; Meyer, M. Immunomodulatory Nanoparticles Induce Autophagy in Macrophages and Reduce Mycobacterium tuberculosis Burden in the Lungs of Mice. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025, 11, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Krishna, V.; Kumari, N.; Banerjee, A.; Kapoor, P. Nano-engineered solutions for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB): A novel nanomedicine. Nano Struct. Nano Objects 2024, 40, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.A. Pharmacodynamics and bactericidal activity of bedaquiline in pulmonary tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e01636-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, T.O.; Poka, M.S.; Witika, B.A. Formulation and optimisation of bedaquiline nanoemulsions for the potential treatment of multi drug resistant tuberculosis in paediatrics using quality by design. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, A.; Ammerman, N.C.; Tasneen, R.; Lachau-Durand, S.; Andries, K.; Nuermberger, E. Efficacy of long-acting bedaquiline regimens in a mouse model of tuberculosis preventive therapy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stemkens, R.; Lemson, A.; Koele, S.E.; Svensson, E.M.; Te Brake, L.H.; van Crevel, R.; Boeree, M.J.; Hoefsloot, W.; van Ingen, J.; Aarnoutse, R.E. A loading dose of clofazimine to rapidly achieve steady-state-like concentrations in patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 3100–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım, M.; Düzgüneş, N. Liposome-Encapsulated Antibiotics for the Therapy of Mycobacterial Infections. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Contreras, L.; Sethuraman, V.; Kazantseva, M.; Hickey, A. Efficacy of combined rifampicin formulations delivered by the pulmonary route to treat tuberculosis in the guinea pig model. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.G.; Dos Santos, R.N.; Oliva, G.; Andricopulo, A.D. Molecular docking and structure-based drug design strategies. Molecules 2015, 20, 13384–13421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Algaleel, S.A.; Abdel-Bar, H.M.; Metwally, A.A.; Hathout, R.M. Evolution of the computational pharmaceutics approaches in the modeling and prediction of drug payload in lipid and polymeric nanocarriers. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javan Nikkhah, S.; Thompson, D. Molecular modelling guided modulation of molecular shape and charge for design of smart self-assembled polymeric drug transporters. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, G.K.; Patra, C.N.; Jammula, S.; Rana, R.; Chand, S. Artificial intelligence and machine learning implemented drug delivery systems: A paradigm shift in the pharmaceutical industry. J. Bio-X Res. 2024, 7, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Perez, A.; van Tilborg, D.; van der Meel, R.; Grisoni, F.; Albertazzi, L. Machine learning-guided high throughput nanoparticle design. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchpuri, M.; Painuli, R.; Kumar, C. Artificial intelligence in smart drug delivery systems: A step toward personalized medicine. RSC Pharm. 2025, 2, 882–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Gadgil, C.J. A physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for tuberculosis drug disposition at extrapulmonary sites. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K.; Balazki, P.; van der Graaf, P.H.; Guo, T.; van Hasselt, J.C. Predictions of bedaquiline central nervous system exposure in patients with tuberculosis meningitis using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2024, 63, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atoyebi, S.; Montanha, M.C.; Nakijoba, R.; Orrell, C.; Mugerwa, H.; Siccardi, M.; Denti, P.; Waitt, C. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of drug–drug interactions between ritonavir-boosted atazanavir and rifampicin in pregnancy. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2024, 13, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchese, J.M.; Dartois, V.; Kirschner, D.E.; Linderman, J.J. Both pharmacokinetic variability and granuloma heterogeneity impact the ability of the first-line antibiotics to sterilize tuberculosis granulomas. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartol, I.R.; Graffigna Palomba, M.S.; Tano, M.E.; Dewji, S.A. Computational multiphysics modeling of radioactive aerosol deposition in diverse human respiratory tract geometries. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Xue, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Xi, Z.; Cui, X. Numerical investigations on the deposition characteristics of lunar dust in the human bronchial airways. Particuology 2025, 97, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintainer, R.; Fochesato, A.; Boaretti, D.; Giampiccolo, S.; Watson, S.; Levi, M.; Reali, F.; Marchetti, L. stormTB: A web-based simulator of a murine minimal-PBPK model for anti-tuberculosis treatments. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 1462193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reali, F.; Fochesato, A.; Kaddi, C.; Visintainer, R.; Watson, S.; Levi, M.; Dartois, V.; Azer, K.; Marchetti, L. A minimal PBPK model to accelerate preclinical development of drugs against tuberculosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1272091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, C.S.C.; Cazorla, J.I.M.; Cazorla, R.M.M.; Roque-Borda, C.A.; Polinario, G.; Banda, R.A.F.; Sabio, R.M.; Chorilli, M.; Santos, H.A.; Pavan, F.R. Breaking barriers: The potential of nanosystems in antituberculosis therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 39, 106–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.D.; Ernest, J.P.; Dide-Agossou, C.; Bauman, A.A.; Ramey, M.E.; Rossmassler, K.; Massoudi, L.M.; Pauly, S.; Al Mubarak, R.; Voskuil, M.I. Lung microenvironments harbor Mycobacterium tuberculosis phenotypes with distinct treatment responses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e00284-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothawade, S.; Shende, P. Coordination bonded stimuli-responsive drug delivery system of chemical actives with metal in pharmaceutical applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 510, 215851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, G.; Faisal, S.; Dorhoi, A. Microenvironments of tuberculous granuloma: Advances and opportunities for therapy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1575133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diacon, A.H.; Dawson, R.; Von Groote-Bidlingmaier, F.; Symons, G.; Venter, A.; Donald, P.R.; Conradie, A.; Erondu, N.; Ginsberg, A.M.; Egizi, E. Randomized dose-ranging study of the 14-day early bactericidal activity of bedaquiline (TMC207) in patients with sputum microscopy smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2199–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.; Ammerman, N.C.; Tyagi, S.; Saini, V.; Vervoort, I.; Lachau-Durand, S.; Nuermberger, E.; Andries, K. Activity of a long-acting injectable bedaquiline formulation in a paucibacillary mouse model of latent tuberculosis infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00007-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Liposome Drug Products: Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls; Human Pharmacokinetics and Bioavailability; and Labeling—Guidance for Industry; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/70837/download? (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Metered Dose Inhaler (MDI) and Dry Powder Inhaler (DPI) Drug Products—Quality Considerations (Draft Guidance); U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. Available online: https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2018-08200.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Reflection Paper on Nanotechnology-Based Medicinal Products for Human Use; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2006; Available online: https://etp-nanomedicine.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/reflection-paper-nanotechnology-based-medicinal-products-human-use_en-1.pdf? (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Active Tuberculosis Drug-Safety Monitoring and Management (aDSM); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/tuberculosis/active-tb-drug-safety-monitoring-and-management-adsm3f6ba713-4a52-4076-9b1d-943bb96cfc55.pdf?sfvrsn=4a28fd4c_1& (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR). In Training Guide for Trainers on Active Tuberculosis Drug Safety Monitoring and Management (aDSM); WARN/CARN-TB; WHO/TDR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://tdr.who.int/docs/librariesprovider10/adsm/adsm-training-guide.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Q13: Continuous Manufacturing of Drug Substances and Drug Products; ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_Q13_Step4_Guideline_2022_1116.pdf? (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Nanotechnology-Based Medicinal Products for Human Use: EU Horizon Scanning Report; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/nanotechnology-based-medicinal-products-human-use-eu-horizon-scanning-report_en.pdf? (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Q12: Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management (Step 5); ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/Q12_Guideline_Step4_2019_1119.pdf? (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Q12 Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management—Guidance for Industry; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/q12-technical-and-regulatory-considerations-pharmaceutical-product-lifecycle-management-guidance? (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Tuberculosis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis? (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Programme on Tuberculosis and Lung Health: The End TB Strategy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/the-end-tb-strategy? (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Rodríguez-Gómez, F.D.; Monferrer, D.; Penon, O.; Rivera-Gil, P. Regulatory pathways and guidelines for nanotechnology-enabled health products: A comparative review of EU and US frameworks. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1544393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TR 10993-22:2017; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices: Part 22: Guidance on Nanomaterials. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65918.html? (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Singh, A.V.; Bhardwaj, P.; Upadhyay, A.K.; Pagani, A.; Upadhyay, J.; Bhadra, J.; Tisato, V.; Thakur, M.; Gemmati, D.; Mishra, R. Navigating regulatory challenges in molecularly tailored nanomedicine. Explor. BioMat-X 2024, 1, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Q2(R2): Validation of Analytical Procedures; ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-q2r2-guideline-validation-analytical-procedures-step-5-revision-1_en.pdf? (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Active Tuberculosis Drug-Safety Monitoring and Management (aDSM)—Programme Page; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/diagnosis-treatment/treatment-of-drug-resistant-tb/active-tb-drug-safety-monitoring-and-management-%28adsm%29? (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Aghajanpour, S.; Amiriara, H.; Esfandyari-Manesh, M.; Ebrahimnejad, P.; Jeelani, H.; Henschel, A.; Singh, H.; Dinarvand, R.; Hassan, S. Utilizing machine learning for predicting drug release from polymeric drug delivery systems. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 188, 109756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.M.; Shah, K.A.; Sunder, S.; Albuquerque, R.Q.; Brütting, C.; Ruckdäschel, H. Machine learning applied to the design and optimization of polymeric materials: A review. Next Mater. 2025, 7, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsard, A.; Genet, M.; Drummond, D. Digital twins for chronic lung diseases. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2024, 33, 240159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Launches New Guidance on the Use of Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Tests for the Diagnosis of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis and a New Sequencing Portal; Departmental Update, 20 March 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-03-2024-who-launches-new-guidance-on-the-use-of-targeted-next-generation-sequencing-tests-for-the-diagnosis-of-drug-resistant-tb-and-a-new-sequencing-portal? (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Jin, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, C.; Li, P.; Hu, C.; Liu, J.; Pan, J. Targeted next-generation sequencing: A promising approach for Mycobacterium tuberculosis detection and drug resistance when applied in paucibacillary clinical samples. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e03127-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, J.; Ohno, M.; Kubota, R.; Yokota, S.; Nagai, T.; Tsuyuguchi, K.; Okuda, Y.; Takashima, T.; Kamimura, S.; Fujio, Y. NAT2 genotype guided regimen reduces isoniazid-induced liver injury and early treatment failure in the 6-month four-drug standard treatment of tuberculosis: A randomized controlled trial for pharmacogenetics-based therapy. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 69, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BioNTech SE. Safety and Immune Responses After Vaccination with Two Investigational RNA-Based Vaccines against Tuberculosis in Healthy Volunteers; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05537038; BioNTech SE: Mainz, Germany, 2025. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05537038 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

| Drug | Drug Class | Primary Molecular Target/Mechanism of Action | Studied Population/Intended Role | Clinical Status | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDQ | Diarylquinoline | Inhibits mycobacterial ATP synthase (c-subunit), blocking ATP generation | MDR-/XDR-TB | Approved; WHO-recommended BPaL/BPaLM regimens | [1,49,50,51,52,53] |

| DLM | Nitroimidazole | F420-dependent prodrug inhibiting mycolic-acid synthesis after activation | DR-TB | Approved (EU/WHO) | [23,49,54,55,56] |

| Pa | Nitroimidazole | F420-dependent prodrug inhibiting cell-wall synthesis and generating reactive nitrogen species | MDR-/XDR-TB | Approved as part of BPaL/BPaLM | [24,56,57,58,59] |

| Quabodepistat (OPC-167832) | DprE1 inhibitor | Inhibits DprE1, blocking arabinan biosynthesis in the mycobacterial cell wall | DS- and DR-TB | Phase 2 (EBA/combination studies) | [45,60] |

| BTZ043 | Benzothiazinone (DprE1 inhibitor) | Covalent inhibition of DprE1 leading to arabinan depletion | DS- and DR-TB | Phase 2 | [56,61,62] |

| Telacebec (Q203) | Imidazopyridine amide | Inhibits cytochrome bc1 complex via QcrB | DS- and DR-TB | Phase 2a | [63,64] |

| Candidate/Class | Primary Target/Mechanism of Action | Stage | Why It Matters | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDQ | ATP synthase (c-subunit) inhibition | Approved; BPaL/BPaLM anchor | Supports short oral DR-TB regimens; resistance through Rv0678 and atpE requires DST and careful pairing | [58] |

| Pa | Nitroimidazole; F420-dependent activation with cell-wall effects | Approved in BPaL/BPaLM | Potent with BDQ and LZD; vulnerable to F420-pathway mutations | [118] |

| DLM | Nitroimidazole; F420-dependent activation | Approved (DR-TB) | Useful in shorter oral combinations; shares F420-pathway risks with Pa | [118] |

| Quabodepistat (OPC-167832) | DprE1 inhibition | Phase 2 (EBA; combinations) | First DprE1 candidate with human EBA and combination activity; DS-TB regimen under study | [45,60] |

| TBA-7371 | DprE1 inhibition | Phase 2a EBA | Dose-dependent 14-day EBA; positioned for combinations | [61] |

| BTZ043 | DprE1 inhibition (benzothiazinone) | Phase 2 | On-target bactericidal activity; promising lesion penetration | [46,119] |

| Macozinone (PBTZ-169) | DprE1 inhibition | Early clinical | Covalent DprE1 inhibitor; ongoing PK/PD refinement | [120] |

| Q203 | QcrB inhibition (cytochrome bc1 complex) | Phase 2a EBA | Human EBA; strong preclinical bactericidal activity; partner for energy-metabolism blockers | [63,64] |

| GSK3036656 (Ganfeborole) | LeuRS inhibition | Phase 2a EBA | First-in-class aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor with human EBA | [47] |

| Sutezolid (PNU-100480) | Oxazolidinone; 50S protein synthesis | Phase 2b | Greater bactericidal effect than LZD; improved safety | [62,121] |

| TBI-223 | Oxazolidinone; 50S protein synthesis | Phase 2 | Retains efficacy with less neuropathy and myelosuppression; promising with BDQ and Pa | [79,122] |

| CFZ | Membrane and electron-transport effects | MDR/XDR-TB use | Improves outcomes; requires QTc monitoring and screening for Rv0678-linked cross-resistance with BDQ | [123] |

| LZD | Oxazolidinone; 50S protein synthesis | Approved (DR-TB) | Dose and duration adjustments preserve efficacy while reducing toxicity | [58,124] |

| Metformin (HDT) | AMPK and mitochondrial activation lead to autophagy | Cohort evidence; RCTs pending | Linked to lower mortality; strong macrophage-level support | [87,88] |

| Statins (HDT) | Enhance autophagy and phagolysosome maturation | Preclinical; mixed clinical findings | Reduce M. tuberculosis burden in models; translational potential | [90,125] |

| Vitamin D | LL-37 induction; immune modulation | RCTs/meta-analyses | Benefits mainly in deficient individuals; modest effects in others | [126] |

| LL-37 strategies | Direct antibacterial and immunomodulatory effects | Preclinical/translational | Nanodelivery improves stability and macrophage targeting | [102,127] |

| Anti-LpqH monoclonal antibody | mAb targeting LpqH on M. tuberculosis | Preclinical | Isotype-dependent protection; foundation for TB-focused ADC platforms | [105] |

| Mycobacteriophage DS6A | Phage-mediated lysis of M. tuberculosis | Preclinical | Active in macrophages and humanized mice; good manufacturing practice (GMP) development needed | [106] |

| CRISPR-TB (diagnostics) | Cas13/Cas12 detection of TB cell-free DNA | Research-grade assays | Enables rapid, non-invasive plasma cfDNA detection | [113,128] |

| LNP–mRNA (CysVac2) | mRNA platform inducing adaptive and innate responses | Preclinical; early human | Strong Th1 responses; candidate as BCG booster or standalone vaccine | [114] |

| Particle Composition | Typical Aerodynamic Size | Key Physicochemical Properties | Primary Biological Effect | Impact on Therapeutic Efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomes (phospholipid-based aerosols) | 1–5 µm | High biocompatibility; encapsulation of hydrophobic drugs; sustained pulmonary residence | Uniform lung distribution and uptake by alveolar macrophages | Achieves bactericidal lung exposure at lower doses and reduces systemic toxicity in preclinical models | [25,127,128] |

| Solid LNPs/nanostructured lipid carriers | 100–300 nm | Lipophilic core; physical stability; controlled drug release | Prolonged retention in lung tissue and intracellular compartments | Maintains local drug concentrations and supports intracellular killing | [27,28,128] |

| Polymeric NPs (e.g., PLGA) | 100–300 nm | Tunable degradation; surface functionalization; ligand attachment (e.g., mannose) | Enhanced uptake by infected macrophages and granulomas | Improves intracellular delivery and lesion-level exposure compared with free drug | [28,128,132,133] |

| Dry-powder inhaler (DPI) microparticles | 1–5 µm | Low moisture content; optimized dispersibility; formulation–device compatibility | Efficient deep-lung deposition without external power | Enables direct lung targeting and improves aerosol performance in translational formulations | [26,29,30] |

| Surface-modified particles (e.g., mannosylated systems) | 100–300 nm | Ligand-mediated targeting; controlled surface charge | Preferential uptake by alveolar macrophages | Increases drug concentration at intracellular bacillary niches | [28,128,134] |

| System Type | Dominant Trigger in TB Lesions | Typical Design Feature | Primary Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH-responsive | Acidic pH in phagosomes and caseous necrosis | Acid-cleavable linkers or pH-sensitive polymer coatings (e.g., chitosan, PLGA blends) | Enables drug release in infected macrophages while remaining stable at physiological pH |

| Enzyme-responsive | Lesion-associated host or mycobacterial enzymes (e.g., esterases, proteases) | Enzyme-cleavable bonds within the carrier or linker | Improves selectivity by releasing drug preferentially in infected tissue |

| Redox-responsive | Elevated intracellular redox gradients and reactive oxygen species | Disulfide or thioketal bonds sensitive to redox conditions | Biases drug release toward intracellular compartments of infected cells |

| Multi-trigger systems | Combined acidic pH with redox or enzymatic cues | Layered or core–shell carriers integrating multiple responsive elements | Enhances spatial and temporal control of drug release |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E.; Abalkhail, A. Advancing Tuberculosis Treatment with Next-Generation Drugs and Smart Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010060

Elbehiry A, Marzouk E, Abalkhail A. Advancing Tuberculosis Treatment with Next-Generation Drugs and Smart Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleElbehiry, Ayman, Eman Marzouk, and Adil Abalkhail. 2026. "Advancing Tuberculosis Treatment with Next-Generation Drugs and Smart Delivery Systems" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010060

APA StyleElbehiry, A., Marzouk, E., & Abalkhail, A. (2026). Advancing Tuberculosis Treatment with Next-Generation Drugs and Smart Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010060