Effect of Treatment with a Combination of Dichloroacetate and Valproic Acid on Adult Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Primary Cells Xenografts on the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. GBM Patient Clinical Data

2.2. GBM Patient Study Groups

2.3. Investigational Medicinal Preparations

2.4. The CAM Model

2.5. Histological and Immunohistochemical Study of the Tumor

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Stereomicroscopic and Histologic Images of Tested Tumors on the CAM In Vivo, the Tumor Ex Ovo, and Their H-E Histological Images

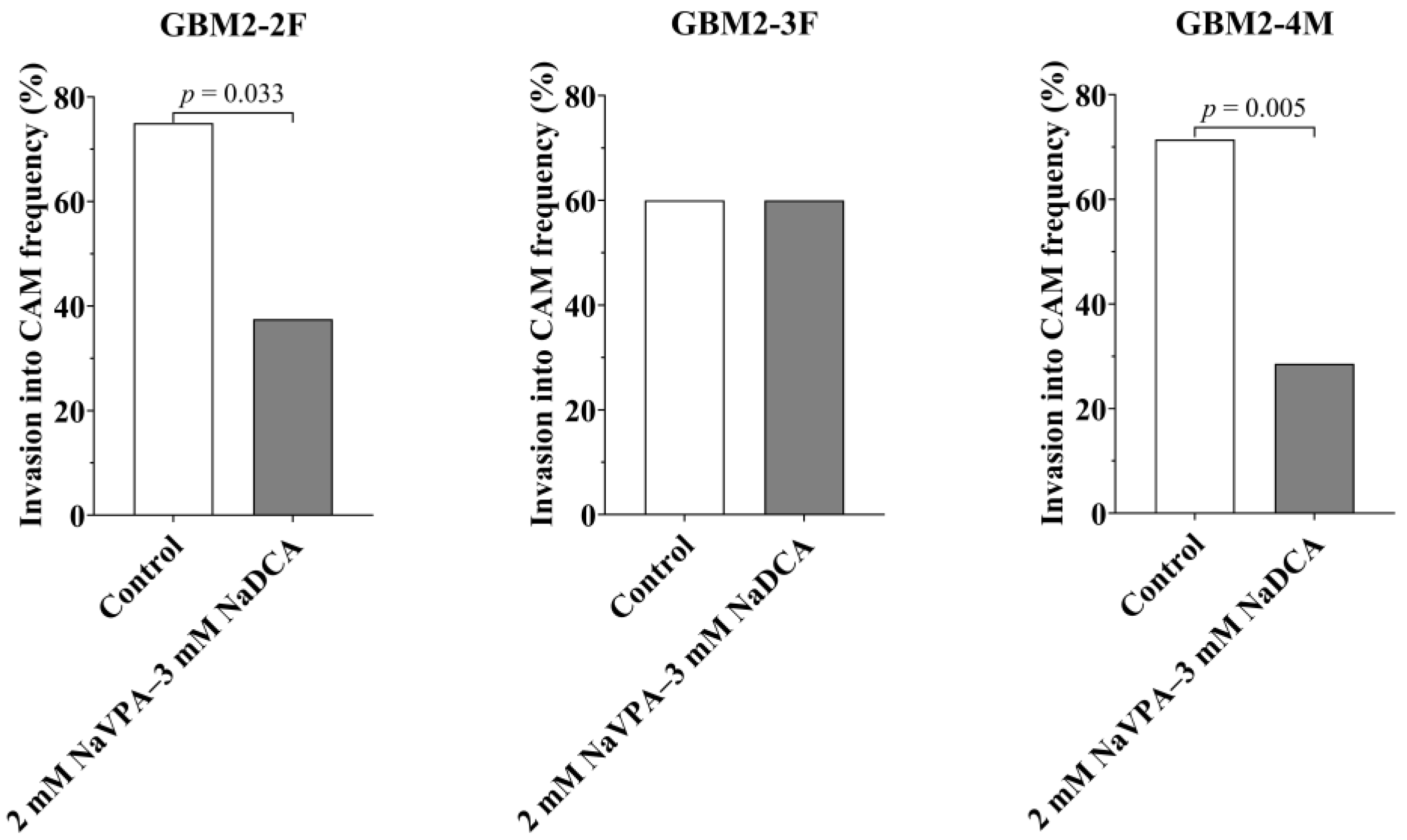

3.2. GBM2-2F, GBM2-3F and GBM2-4M Tumors’ Growth, Tumor Invasion Rate into CAM, the IMP Impact on Neo-Angiogenesis and CAM Thickness Under the Tumor

3.3. GBM2-2F, GBM2-3F and GBM2-4M Immunohistochemical Examination of GFAP, PCNA, p53, EZH2 and Vimentin Markers Expression in the Tested Tumors on CAM

3.3.1. The GFAP Expression in GBM-Resected Tumor Tissue of Studied Patients and Tumors Formed by Tumor Cells on CAM

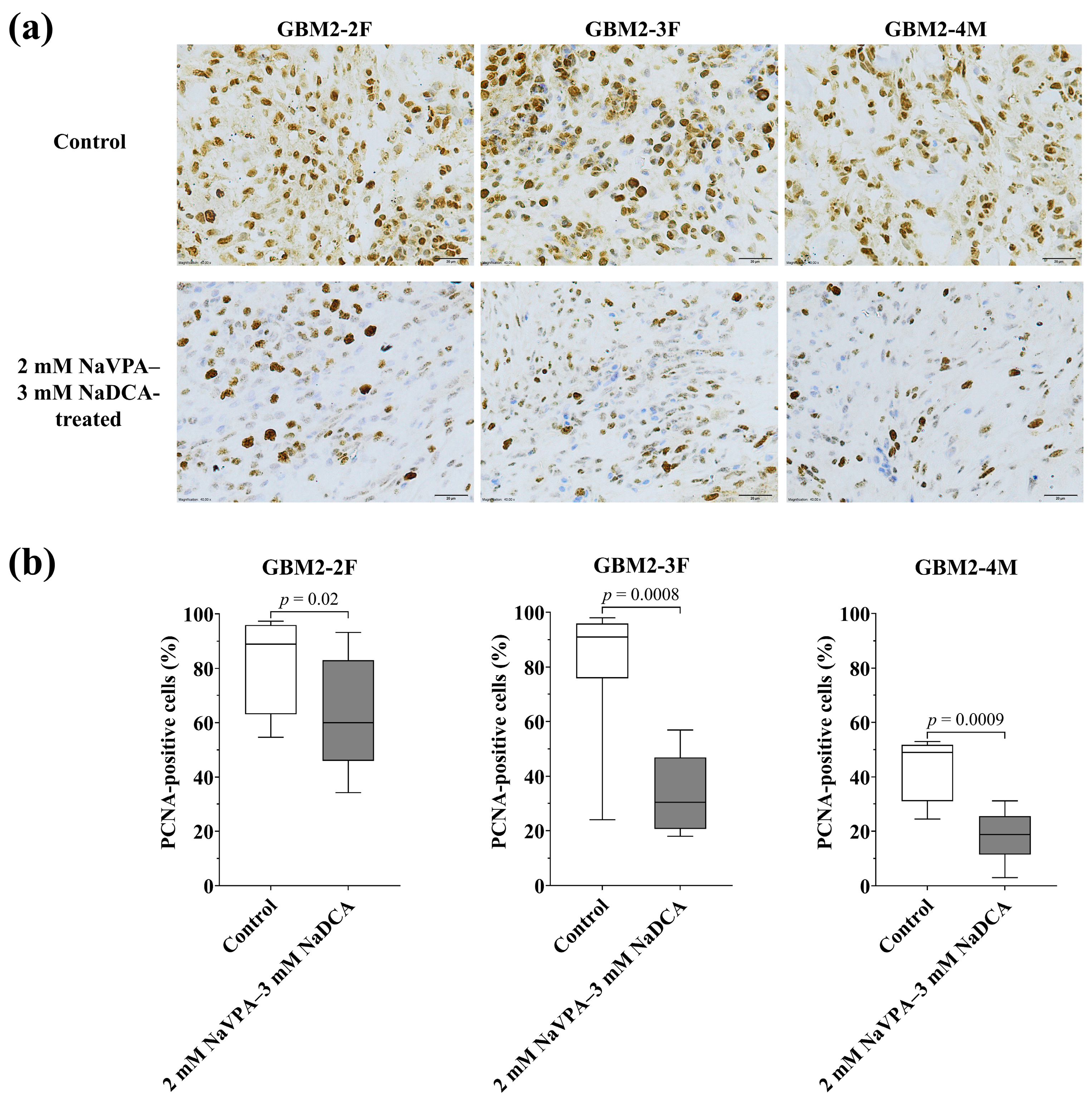

3.3.2. The PCNA Expression of GBM Tumors in Control and Treated Groups

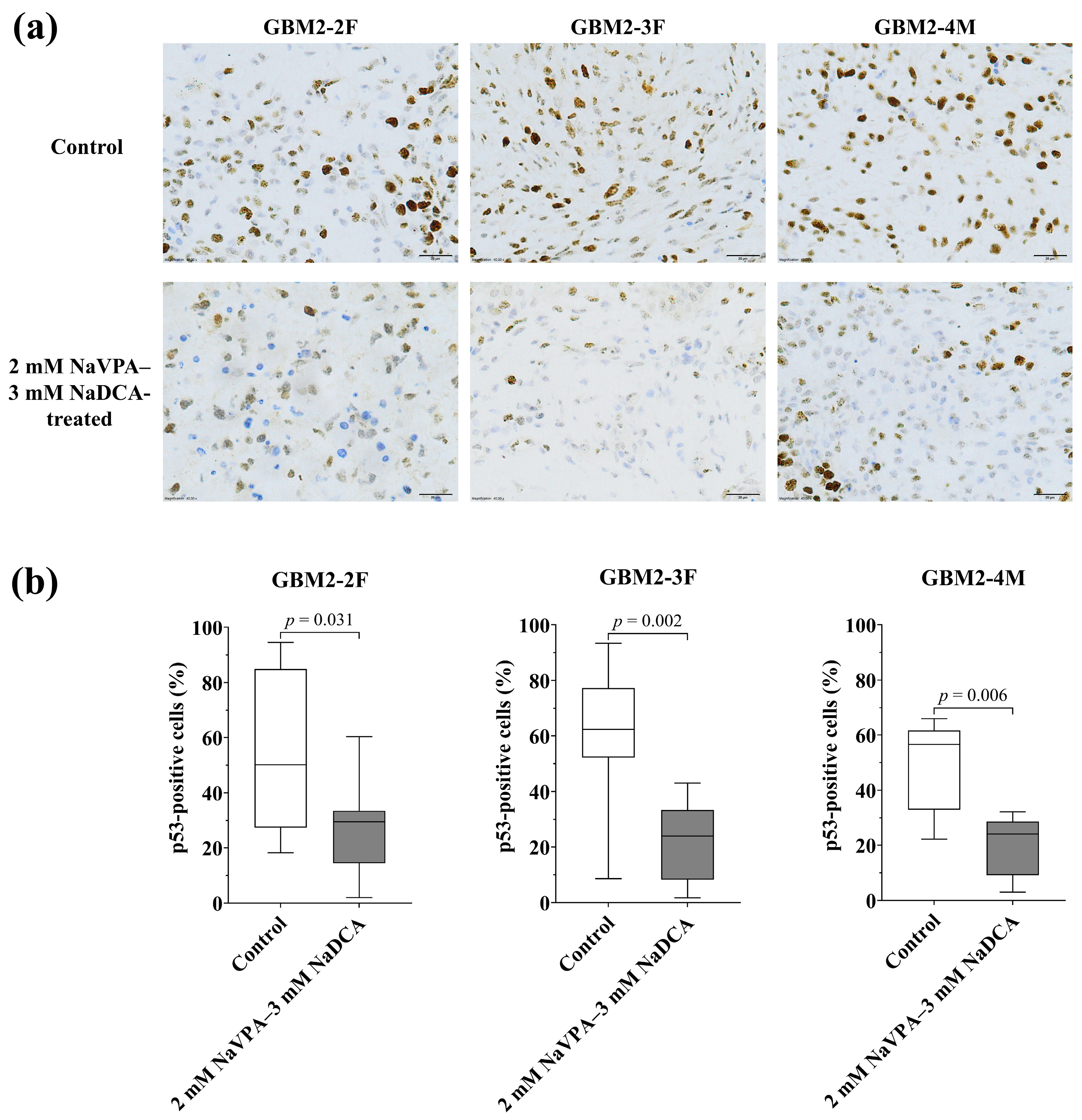

3.3.3. The p53 Expression of GBM Tumors in Control and Treated Groups

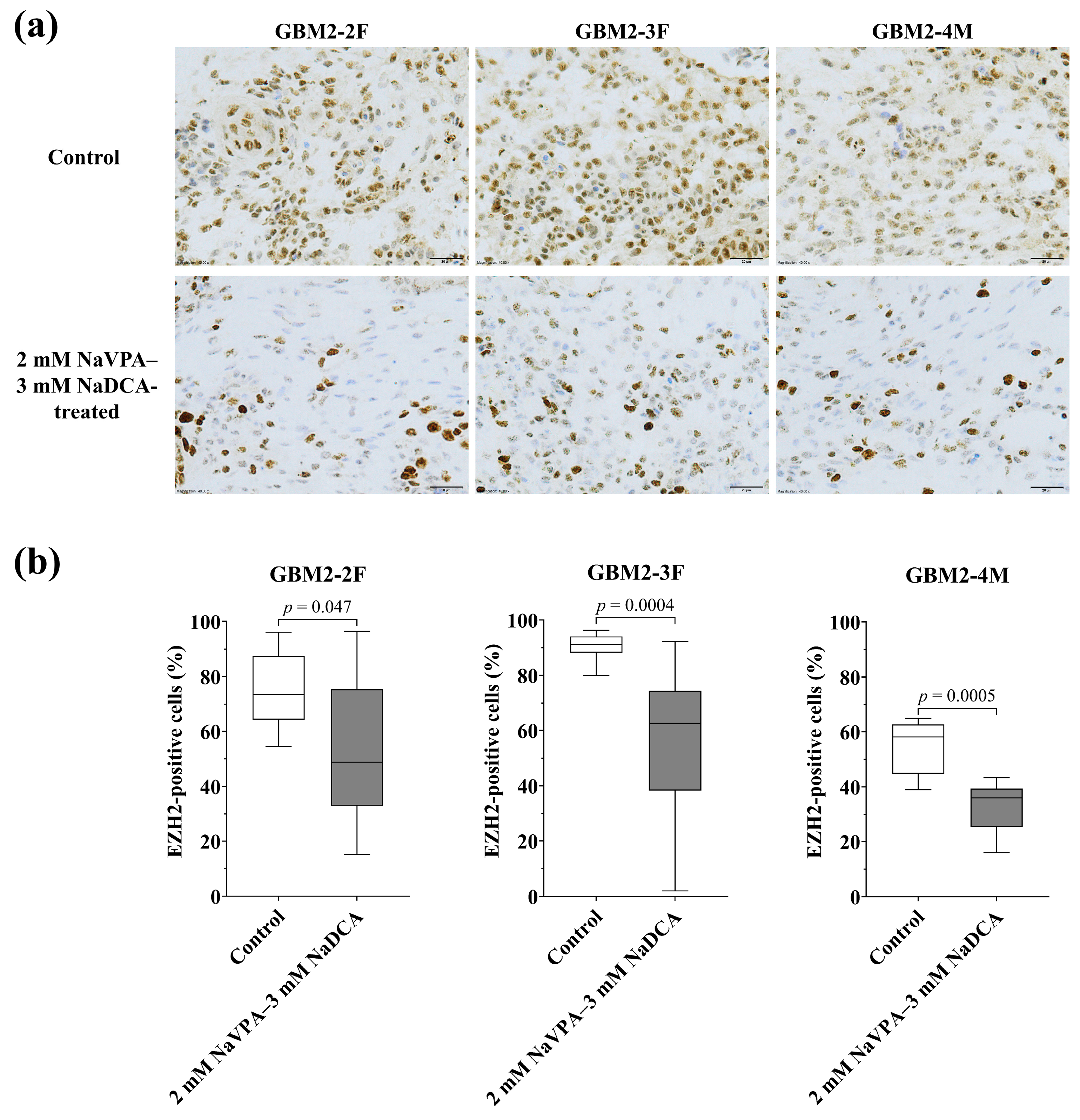

3.3.4. The EZH2 Expression of GBM Tumors in Control and Treated Groups

3.3.5. The Vimentin Expression in the Studied GBM Tumors in the Control and Treated Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Glioblastoma tumors formed from patients’ primary cells on CAM retain tumor GFAP expression, indicating that the CAM model is reliable for studying the properties of the tumor.

- Preclinical in vivo studies using the CAM model indicate that NaVPA–NaDCA has an anticancer effect on GFAP, p53, PCNA, EZH2, and vimentin GBM markers expression, which is important for carcinogenesis.

- The CAM model is informative for assessing the efficacy of the investigational drug in glioma primary cell tumors and may be a relevant tool for evaluating the potential effectiveness of chemotherapy; however, the expected effect of the drug should be assessed individually.

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAM | Chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane |

| DCA | Dichloroacetate |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium for cell culture |

| EDD | Day of embryo development |

| EZH2 | Polycomb inhibitory complex catalytic subunit 2 |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| H-E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| IDH | Isocitrate dehydrogenase |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| NaDCA | Sodium dichloroacetate |

| NaVPA–NaDCA | Combination of sodium dichloroacetate and sodium valproate |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| PDH | Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

| PDK | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase |

| PDX | Patient-derived xenograft model |

| p53 | TP53 gene-encoded p53 protein |

| P/S | Penicillin and streptomycin |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| VPA | Valproic acid |

Appendix A

| Patient Study Group | n | GFAP-Positive Cells (%), Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|

| GBM2-2F | ||

| GBM patient tumor tissue | 10 | 93.70 (72.56–100.00) |

| Control tumor on CAM | 8 | 80.24 (23.61–97.45) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 12 | 55.83 (10.10–93.60) |

| GBM2-3F | ||

| GBM patient tumor tissue | 10 | 89.44 (83.56–95.65) |

| Control tumor on CAM | 12 | 82.63 (75.05–90.63) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 44.38 (8.00–68.65) a |

| GBM2-4M | ||

| GBM patient tumor tissue | 10 | 85.88 (76.00–100.00) |

| Control tumor on CAM | 8 | 76.00 (69.06–89.00) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 39.92 (32.00–76.00) b |

| Patient Study Group | n | PCNA-Positive Cells (%), Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|

| GBM2-2F | ||

| Control | 8 | 88.88 (54.60–97.30) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 12 | 59.95 (34.31–93.20) a |

| GBM2-3F | ||

| Control | 12 | 90.95 (24.00–98.00) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 30.35 (18.00–56.91) b |

| GBM2-4M | ||

| Control | 8 | 49.00 (24.43–53.00) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 18.79 (3.00–31.10) c |

| Patient Study Group | n | p53-Positive Cells (%), Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|

| GBM2-2F | ||

| Control | 8 | 50.13 (18.23–94.54) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 12 | 29.54 (2.01–60.32) a |

| GBM2-3F | ||

| Control | 12 | 62.34 (8.60–93.33) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 23.93 (1.73–43.05) b |

| GBM2-4M | ||

| Control | 8 | 56.58 (22.19–66.00) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 24.00 (3.00–32.19) c |

| Patient Study Group | n | EZH2-Positive Cells (%), Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|

| GBM2-2F | ||

| Control | 8 | 73.48 (54.52–96.08) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 12 | 48.73 (15.21–96.40) a |

| GBM2-3F | ||

| Control | 12 | 91.11 (79.90–96.22) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 62.50 (2.00–92.17) b |

| GBM2-4M | ||

| Control | 8 | 58.11 (39.00–65.00) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 36.00 (16.00–43.36) c |

| Patient Study Group | n | Vimentin-Positive Cells (%), Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|

| GBM2-2F | ||

| Control | 8 | 45.85 (19.20–76.45) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 12 | 13.94 (2.02–56.02) a |

| GBM2-3F | ||

| Control | 12 | 26.91 (2.15–91.00) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 5.14 (1.18–31.25) b |

| GBM2-4M | ||

| Control | 8 | 79.00 (35.38–89.00) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 10 | 49.50 (29.00–70.72) c |

References

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Gittleman, H.; Patil, N.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro-Oncol. 2019, 21, v1–v100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2014-2018. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 23, III1–III105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalamarty, S.S.K.; Filipczak, N.; Li, X.; Subhan, M.A.; Parveen, F.; Ataide, J.A.; Rajmalani, B.A.; Torchilin, V.P. Mechanisms of Resistance and Current Treatment Options for Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). Cancers 2023, 15, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.C.; Ashley, D.M.; López, G.Y.; Malinzak, M.; Friedman, H.S.; Khasraw, M. Management of Glioblastoma: State of the Art and Future Directions. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Gilbert, M.R.; Chakravarti, A. Chemoradiotherapy in Malignant Glioma: Standard of Care and Future Directions. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4127–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, G.; Rahman, R. Evolution of Preclinical Models for Glioblastoma Modelling and Drug Screening. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 27, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xue, D.; Bankhead, A.; Neamati, N. Why All the Fuss about Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS)? J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 14276–14307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ho, W.S.; Lu, R. Targeting Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation in Glioblastoma Therapy. NeuroMolecular Med. 2022, 24, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrieu, C.M.; Storevik, S.; Guyon, J.; Pagano Zottola, A.C.; Bouchez, C.L.; Derieppe, M.A.; Tan, T.Z.; Miletic, H.; Lorens, J.; Tronstad, K.J.; et al. Refining the Role of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinases in Glioblastoma Development. Cancers 2022, 14, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinopoulos, C.; Seyfried, T.N. Mitochondrial Substrate-Level Phosphorylation as Energy Source for Glioblastoma: Review and Hypothesis. ASN Neuro 2018, 10, 1759091418818261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Yu, M.; Tsoli, M.; Chang, C.; Joshi, S.; Liu, J.; Ryall, S.; Chornenkyy, Y.; Siddaway, R.; Hawkins, C.; et al. Targeting Reduced Mitochondrial DNA Quantity as a Therapeutic Approach in Pediatric High-Grade Gliomas. Neuro-Oncol. 2020, 22, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutendra, G.; Michelakis, E.D. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase as a Novel Therapeutic Target in Oncology. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankotia, S.; Stacpoole, P.W. Dichloroacetate and Cancer: New Home for an Orphan Drug? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2014, 1846, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Nagaraja, N.V.; Hutson, A.D. Efficacy of Dichloroacetate as a Lactate-Lowering Drug. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003, 43, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakišaitis, D.; Damanskienė, E.; Curkūnavičiūtė, R.; Juknevičienė, M.; Alonso, M.M.; Valančiūtė, A.; Ročka, S.; Balnytė, I. The Effectiveness of Dichloroacetate on Human Glioblastoma Xenograft Growth Depends on Na+ and Mg2+ Cations. Dose-Response 2021, 19, 1559325821990166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Hau, E.; Joshi, S.; Dilda, P.J.; McDonald, K.L. Sensitization of Glioblastoma Cells to Irradiation by Modulating the Glucose Metabolism. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Guan, W. Valproic Acid: A Promising Therapeutic Agent in Glioma Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 687362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.Y.; Li, J.R.; Wu, C.C.; Ou, Y.C.; Chen, W.Y.; Kuan, Y.H.; Wang, W.Y.; Chen, C.J. Valproic Acid Sensitizes Human Glioma Cells to Gefitinib-Induced Autophagy. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.; Wang, J.; Hong, M.; Zheng, L.; Tong, Q. Valproic Acid Suppresses Warburg Effect and Tumor Progression in Neuroblastoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 508, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, E.; Ramachandran, S.; Coothankandaswamy, V.; Elangovan, S.; Prasad, P.D.; Ganapathy, V.; Thangaraju, M. Role of SLC5A8, a Plasma Membrane Transporter and a Tumor Suppressor, in the Antitumor Activity of Dichloroacetate. Oncogene 2011, 30, 4026–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronezi, G.M.B.; Felisbino, M.B.; Gatti, M.S.V.; Mello, M.L.S.; De Vidal, B.C. DNA Methylation Changes in Valproic Acid-Treated HeLa Cells as Assessed by Image Analysis, Immunofluorescence and Vibrational Microspectroscopy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Miner, A.; Hennis, L.; Mittal, S. Mechanisms of Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma—A Comprehensive Review. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavaliauskaitė, D.; Stakišaitis, D.; Martinkutė, J.; Šlekienė, L.; Kazlauskas, A.; Balnytė, I.; Lesauskaitė, V.; Valančiūtė, A. The Effect of Sodium Valproate on the Glioblastoma U87 Cell Line Tumor Development on the Chicken Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane and on EZH2 and P53 Expression. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 6326053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skredėnienė, R.; Stakišaitis, D.; Valančiūtė, A.; Balnytė, I. In Vivo and In Vitro Experimental Study Comparing the Effect of a Combination of Sodium Dichloroacetate and Valproic Acid with That of Temozolomide on Adult Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamri, M.S.; McClellan, B.L.; Hartlage, M.S.; Haase, S.; Faisal, S.M.; Thalla, R.; Dabaja, A.; Banerjee, K.; Carney, S.V.; Mujeeb, A.A.; et al. Targeting Neuroinflammation in Brain Cancer: Uncovering Mechanisms, Pharmacological Targets, and Neuropharmaceutical Developments. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 680021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeCordova, S.; Shastri, A.; Tsolaki, A.G.; Yasmin, H.; Klein, L.; Singh, S.K.; Kishore, U. Molecular Heterogeneity and Immunosuppressive Microenvironment in Glioblastoma. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakišaitis, D.; Kapočius, L.; Tatarūnas, V.; Gečys, D.; Mickienė, A.; Tamošuitis, T.; Ugenskienė, R.; Vaitkevičius, A.; Balnytė, I.; Lesauskaitė, V. Effects of Combined Treatment with Sodium Dichloroacetate and Sodium Valproate on the Genes in Inflammation- and Immune-Related Pathways in T Lymphocytes from Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection with Pneumonia: Sex-Related Differences. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakišaitis, D.; Kapočius, L.; Kilimaitė, E.; Gečys, D.; Šlekienė, L.; Balnytė, I.; Palubinskienė, J.; Lesauskaitė, V. Preclinical Study in Mouse Thymus and Thymocytes: Effects of Treatment with a Combination of Sodium Dichloroacetate and Sodium Valproate on Infectious Inflammation Pathways. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, M.; Harper, K.; Brochu-Gaudreau, K.; Perreault, A.; Roy, L.O.; Lucien, F.; Tian, S.; Fortin, D.; Dubois, C.M. The Development of a Rapid Patient-Derived Xenograft Model to Predict Chemotherapeutic Drug Sensitivity/Resistance in Malignant Glial Tumors. Neuro-Oncol. 2023, 25, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.A. Using Pdx for Preclinical Cancer Drug Discovery: The Evolving Field. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Bodegraven, E.J.; van Asperen, J.V.; Robe, P.A.J.; Hol, E.M. Importance of GFAP Isoform-Specific Analyses in Astrocytoma. Glia 2019, 67, 1417–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simone, L.; Capobianco, D.L.; Di Palma, F.; Binda, E.; Legnani, F.G.; Vescovi, A.L.; Svelto, M.; Pisani, F. GFAP Serves as a Structural Element of Tunneling Nanotubes between Glioblastoma Cells and Could Play a Role in the Intercellular Transfer of Mitochondria. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1221671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadipour, Y.; Gembruch, O.; Pierscianek, D.; Sure, U.; Jabbarli, R. Does the Expression of Glial Fibrillary Acid Protein (GFAP) Stain in Glioblastoma Tissue Have a Prognostic Impact on Survival? Neurochirurgie 2020, 66, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzińska-Ustymowicz, K.; Pryczynicz, A.; Kemona, A.; Czyzewska, J. Correlation between Proliferation Markers: PCNA, Ki-67, MCM-2 and Antiapoptotic Protein Bcl-2 in Colorectal Cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2009, 29, 3049–3052. [Google Scholar]

- Korshunov, A.; Golanov, A.; Sycheva, R.; Pronin, I. Prognostic Value of Tumour Associated Antigen Immunoreactivity and Apoptosis in Cerebral Glioblastomas: An Analysis of 168 Cases. J. Clin. Pathol. 1999, 52, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Morris, G.F. P53-Mediated Regulation of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen Expression in Cells Exposed to Ionizing Radiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Carlsen, L.; Hernandez Borrero, L.; Seyhan, A.A.; Tian, X.; El-Deiry, W.S. Advanced Strategies for Therapeutic Targeting of Wild-Type and Mutant P53 in Cancer. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.C.; Lowe, S.W. Mutant P53: It’s Not All One and the Same. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babamohamadi, M.; Babaei, E.; Ahmed Salih, B.; Babamohammadi, M.; Jalal Azeez, H.; Othman, G. Recent Findings on the Role of Wild-Type and Mutant P53 in Cancer Development and Therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 903075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanapathipillai, M. Treating P53 Mutant Aggregation-Associated Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaeva, N. P53 Signaling in Cancers. Cancers 2019, 11, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.J.; Synnott, N.C.; Crown, J. Mutant P53 as a Target for Cancer Treatment. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 83, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hou, S.; Jiang, R.; Sun, J.; Cheng, C.; Qian, Z. EZH2 Is a Potential Prognostic Predictor of Glioma. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Han, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Pu, P.; Kang, C. EZH2 Is a Negative Prognostic Factor and Exhibits Pro-Oncogenic Activity in Glioblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2015, 356, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.J.; Hung, M.C. The Role of EZH2 in Tumour Progression. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.A.; Lange, C.A. Roles of the EZH2 Histone Methyltransferase in Cancer Epigenetics. Mutat. Res.-Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2008, 647, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitzlein, L.M.; Adams, J.T.; Stitzlein, E.N.; Dudley, R.W.; Chandra, J. Current and Future Therapeutic Strategies for High-Grade Gliomas Leveraging the Interplay between Epigenetic Regulators and Kinase Signaling Networks. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Y.; Ma, W.; Lu, S.; He, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; et al. Vimentin Promotes Glioma Progression and Maintains Glioma Cell Resistance to Oxidative Phosphorylation Inhibition. Cell. Oncol. 2023, 46, 1791–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, M.; Neilson, E.G. Biomarkers for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.W.; Huang, B.R.; Liu, Y.S.; Lin, H.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Tsai, C.F.; Lu, D.Y.; Lin, C. Differential Characterization of Temozolomide-Resistant Human Glioma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zottel, A.; Jovčevska, I.; Šamec, N.; Komel, R. Cytoskeletal Proteins as Glioblastoma Biomarkers and Targets for Therapy: A Systematic Review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 160, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stakišaitis, D.; Valančiūtė, A.; Balnyte, I.; Lesauskaite, V.; Jukneviciene, M.; Staneviciene, J.; Juozas, J.D. Valpro Rūgšties ir Dichloroacetato Druskų Derinio Taikymas Vėžio Gydymui. LT6874B, 25 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Patent Application. Derivative of Valproic Acid and Dichloroacetate Used for the Treatment of Cancer. European Patent Application No. 21168796.7, 16 April 2021. Available online: https://register.epo.org/application?number=EP21168796 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Šlekienė, L.; Stakišaitis, D.; Balnytė, I.; Valančiūtė, A. Sodium Valproate Inhibits Small Cell Lung Cancer Tumor Growth on the Chicken Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane and Reduces the P53 and EZH2 Expression. Dose-Response 2018, 16, 1559325818772486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D. Chapter 5 Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane as a Useful Tool to Study Angiogenesis. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008, 270, 181–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angom, R.S.; Nakka, N.M.R.; Bhattacharya, S. Advances in Glioblastoma Therapy: An Update on Current Approaches. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rončević, A.; Koruga, N.; Soldo Koruga, A.; Rončević, R.; Rotim, T.; Šimundić, T.; Kretić, D.; Perić, M.; Turk, T.; Štimac, D. Personalized Treatment of Glioblastoma: Current State and Future Perspective. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.Y.; Koh, A.P.F.; Antony, J.; Huang, R.Y.J. Applications of the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane as an Alternative Model for Cancer Studies. Cells Tissues Organs 2022, 211, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D. The Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane in the Study of Angiogenesis and Metastasis: The CAM Assay in the Study of Angiogenesis and Metastasis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, N.; Kinney, T.D.; Mason, E.J.; Prieto, L.C. Maintenance of Human Neoplasm on the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane. Am. J. Pathol. 1956, 32, 271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Ausprunk, D.H.; Knighton, D.R.; Folkman, J. Vascularization of Normal and Neoplastic Tissues Grafted to the Chick Chorioallantois. Role of Host and Preexisting Graft Blood Vessels. Am. J. Pathol. 1975, 79, 597–618. [Google Scholar]

- Uloza, V.; Kuzminienė, A.; Šalomskaitė-Davalgienė, S.; Palubinskienė, J.; Balnytė, I.; Ulozienė, I.; Šaferis, V.; Valančiūtė, A. Effect of Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Tissue Implantation on the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane: Morphometric Measurements and Vascularity. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 629754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Vacca, A.; Roncali, L.; Dammacco, F. The Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane as a Model for in Vivo Research on Angiogenesis. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1996, 40, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balčiūnienė, N.; Tamašauskas, A.; Valančiūtė, A.; Deltuva, V.; Vaitiekaitis, G.; Gudinavičienė, I.; Weis, J.; von Keyserlingk, D.G. Histology of Human Glioblastoma Transplanted on Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane. Medicina 2009, 45, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gečys, D.; Akramas, L.; Preikšaitis, A.; Balnytė, I.; Vaitkevičius, A.; Šimienė, J.; Stakišaitis, D. Comparison of the Effect of the Combination of Sodium Valproate and Sodium Dichloroacetate on the Expression of SLC12A2, SLC12A5, CDH1, CDH2, EZH2, and GFAP in Primary Female Glioblastoma Cells with That of Temozolomide. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escartin, C.; Galea, E.; Lakatos, A.; O’Callaghan, J.P.; Petzold, G.C.; Serrano-Pozo, A.; Steinhäuser, C.; Volterra, A.; Carmignoto, G.; Agarwal, A.; et al. Reactive Astrocyte Nomenclature, Definitions, and Future Directions. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, M.; Zou, W.Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, S.; Lv, Y.; Su, L.; Ji, F.; Jiao, J.; Gao, Y. Ezh2 Regulates Early Astrocyte Morphogenesis and Influences the Coverage of Astrocytic Endfeet on the Vasculature. Cell Prolif. 2025, 58, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sereika, M.; Urbanaviciute, R.; Tamasauskas, A.; Skiriute, D.; Vaitkiene, P. GFAP Expression Is Influenced by Astrocytoma Grade and Rs2070935 Polymorphism. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 4496–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen Has an Association with Prognosis and Risks Factors of Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 6209–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, M.; Karimian-Jazi, K.; Hoffmann, D.C.; Rauschenbach, L.; Simon, M.; Hai, L.; Mandelbaum, H.; Schubert, M.C.; Kessler, T.; Uhlig, S.; et al. Individual Glioblastoma Cells Harbor Both Proliferative and Invasive Capabilities during Tumor Progression. Neuro-Oncol. 2023, 25, 2150–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, M.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y. Targeting P53 Pathways: Mechanisms, Structures, and Advances in Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AghaAmiri, S.; Ghosh, S.C.; Hernandez Vargas, S.; Halperin, D.M.; Azhdarinia, A. Somatostatin Receptor Subtype-2 Targeting System for Specific Delivery of Temozolomide. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.R.; Wang, M.; Aldape, K.D.; Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Jaeckle, K.A.; Armstrong, T.S.; Wefel, J.S.; Won, M.; Blumenthal, D.T.; et al. Dose-Dense Temozolomide for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma: A Randomized Phase III Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 4085–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Rhun, E.; Preusser, M.; Roth, P.; Reardon, D.A.; van den Bent, M.; Wen, P.; Reifenberger, G.; Weller, M. Molecular Targeted Therapy of Glioblastoma. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2019, 80, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.Y.; Ko, H.J.; Chiou, S.J.; Lai, Y.L.; Hou, C.C.; Javaria, T.; Huang, Z.Y.; Cheng, T.S.; Hsu, T.I.; Chuang, J.Y.; et al. Nbm-Bmx, an Hdac8 Inhibitor, Overcomes Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma Multiforme by Downregulating the β-Catenin/c-Myc/Sox2 Pathway and Upregulating P53-Mediated Mgmt Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osanai, T.; Takagi, Y.; Toriya, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Aruga, T.; Iida, S.; Uetake, H.; Sugihara, K. Inverse Correlation between the Expression of O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyl Transferase (MGMT) and P53 in Breast Cancer. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 35, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.H.; Yoon, W.S.; Park, K.Y.; Kim, S.M.; Lim, J.Y.; Woo, J.S.; Jeong, C.H.; Hou, Y.; Jeun, S.S. Valproic Acid Downregulates the Expression of MGMT and Sensitizes Temozolomide-Resistant Glioma Cells. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 987495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xia, Y.; Bu, X.; Yang, D.; Yuan, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, J. Effects of Valproic Acid on the Susceptibility of Human Glioma Stem Cells for TMZ and ACNU. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 9877–9883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Deng, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, G.; Feng, M.; Zhou, Y. Targeting EZH2 regulates the biological characteristics of glioma stem cells via the Notch1 pathway. Exp. Brain Res. 2023, 241, 2409–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, S.; You, H.; Chen, J.; Wu, Q.; Yin, K.; Lin, F.; Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; Ding, C.; et al. Integrating Metabolic RNA Labeling-Based Time-Resolved Single-Cell RNA Sequencing with Spatial Transcriptomics for Spatiotemporal Transcriptomic Analysis. Small Methods 2025, 9, e2401297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtakoivu, R.; Mai, A.; Mattila, E.; De Franceschi, N.; Imanishi, S.Y.; Corthals, G.; Kaukonen, R.; Saari, M.; Cheng, F.; Torvaldson, E.; et al. Vimentin-ERK Signaling Uncouples Slug Gene Regulatory Function. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 2349–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iser, I.C.; Pereira, M.B.; Lenz, G.; Wink, M.R. The Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition-Like Process in Glioblastoma: An Updated Systematic Review and In Silico Investigation. Med. Res. Rev. 2017, 37, 271–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyritsi, K.; Ye, J.; Douglass, E.; Pacholczyk, R.; Tsuboi, N.; Otani, Y.; Wang, Q.; Munn, D.H.; Kaur, B.; Hong, B. Brain CD73 Modulates Interferon Signaling to Regulate Glioblastoma Invasion. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2025, 7, vdaf080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, U.; Ha, G.; Tseng, Y.Y.; Greenwald, N.F.; Oh, C.; Shih, J.; McFarland, J.M.; Wong, B.; Boehm, J.S.; Beroukhim, R.; et al. Patient-Derived Xenografts Undergo Mouse-Specific Tumor Evolution. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, G.J. Applications of Patient-Derived Tumor Xenograft Models and Tumor Organoids. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Tang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yin, G.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, F. Patient-Derived Xenografts of Different Grade Gliomas Retain the Heterogeneous Histological and Genetic Features of Human Gliomas. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Chen, S.; Guo, Y.; Li, W.; Qi, X.; Yang, H.; Xiao, S.; Fang, G.; Hu, J.; Wen, C.; et al. Establishment and Evaluation of Four Different Types of Patient-Derived Xenograft Models. Cancer Cell Int. 2017, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, K.M.; Kim, J.; Jin, J.; Kim, M.; Seol, H.J.; Muradov, J.; Yang, H.; Choi, Y.L.; Park, W.Y.; Kong, D.S.; et al. Patient-Specific Orthotopic Glioblastoma Xenograft Models Recapitulate the Histopathology and Biology of Human Glioblastomas In Situ. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.F.; Zhang, Q.B.; Dong, J.; Diao, Y.; Wang, Z.M.; Li, R.J.; Wu, Z.C.; Wang, A.D.; Lan, Q.; Zhang, S.M.; et al. Development of Clinically Relevant Orthotopic Xenograft Mouse Model of Metastatic Lung Cancer and Glioblastoma through Surgical Tumor Tissues Injection with Trocar. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 29, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, D.; Mullins, C.S.; Schneider, B.; Orthmann, A.; Lamp, N.; Krohn, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Classen, C.F.; Linnebacher, M. Optimized Creation of Glioblastoma Patient Derived Xenografts for Use in Preclinical Studies. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, W.; Yi, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y. The Application of Histone Deacetylases Inhibitors in Glioblastoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient Study Group | Invasion, CAM Thickness | GFAP, PCNA, p53, EZH2, Vimentin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Tumors on CAM | ||||||

| GBM2 -2F | GBM2 -3F | GBM2 -4M | GBM2 -2F | GBM2-3F | GBM2 -4M | |

| Control | 8 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 8 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Patient Study Group | n | Invasion Frequency (%) | CAM Thickness (µm), Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBM2-2F | |||

| Control | 16 | 75.00 | 201.80 (47.32–677.70) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 16 | 37.50 a | 403.10 (150.30–672.20) |

| GBM2-3F | |||

| Control | 20 | 60.00 | 398.6 0 (98.00–675.60) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 20 | 60.00 | 422.70 (100.05–782.40) |

| GBM2-4M | |||

| Control | 14 | 71.43 | 201.30 (44.77–350.10) |

| 2 mM NaVPA–3 mM NaDCA-treated | 14 | 28.57 b | 171.40 (120.10–356.50) c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Skredėnienė, R.; Stakišaitis, D.; Preikšaitis, A.; Valančiūtė, A.; Lesauskaitė, V.; Balnytė, I. Effect of Treatment with a Combination of Dichloroacetate and Valproic Acid on Adult Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Primary Cells Xenografts on the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010052

Skredėnienė R, Stakišaitis D, Preikšaitis A, Valančiūtė A, Lesauskaitė V, Balnytė I. Effect of Treatment with a Combination of Dichloroacetate and Valproic Acid on Adult Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Primary Cells Xenografts on the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkredėnienė, Rūta, Donatas Stakišaitis, Aidanas Preikšaitis, Angelija Valančiūtė, Vaiva Lesauskaitė, and Ingrida Balnytė. 2026. "Effect of Treatment with a Combination of Dichloroacetate and Valproic Acid on Adult Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Primary Cells Xenografts on the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010052

APA StyleSkredėnienė, R., Stakišaitis, D., Preikšaitis, A., Valančiūtė, A., Lesauskaitė, V., & Balnytė, I. (2026). Effect of Treatment with a Combination of Dichloroacetate and Valproic Acid on Adult Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Primary Cells Xenografts on the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010052