Antibiofilm and Immunomodulatory Effects of Cinnamaldehyde in Corneal Epithelial Infection Models: Ocular Treatments Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals, Microbial Strains and Clture Conditions

2.2. Antibacterial Activity of Trans-Cinnamaldehyde Against K. pneumoniae

2.3. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

2.4. Biofilm Eradication Assay Using CV and XTT

2.5. Bacterial Biofilm Attachment and Proliferation in Contect Lens

2.5.1. Biofilm Evaluation Using Fluorescence Studies

2.5.2. Quantification of Nitric Oxide in the HCEC–Biofilm Co-Culture System

2.6. Quantification of Internalized Bacteria (Antibiotic Protection Assay)

2.7. HCEC Corneal Cell Migration Assay

2.8. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.9. Computational Analysis of MrkH and Cinnamaldehyde Interactions

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

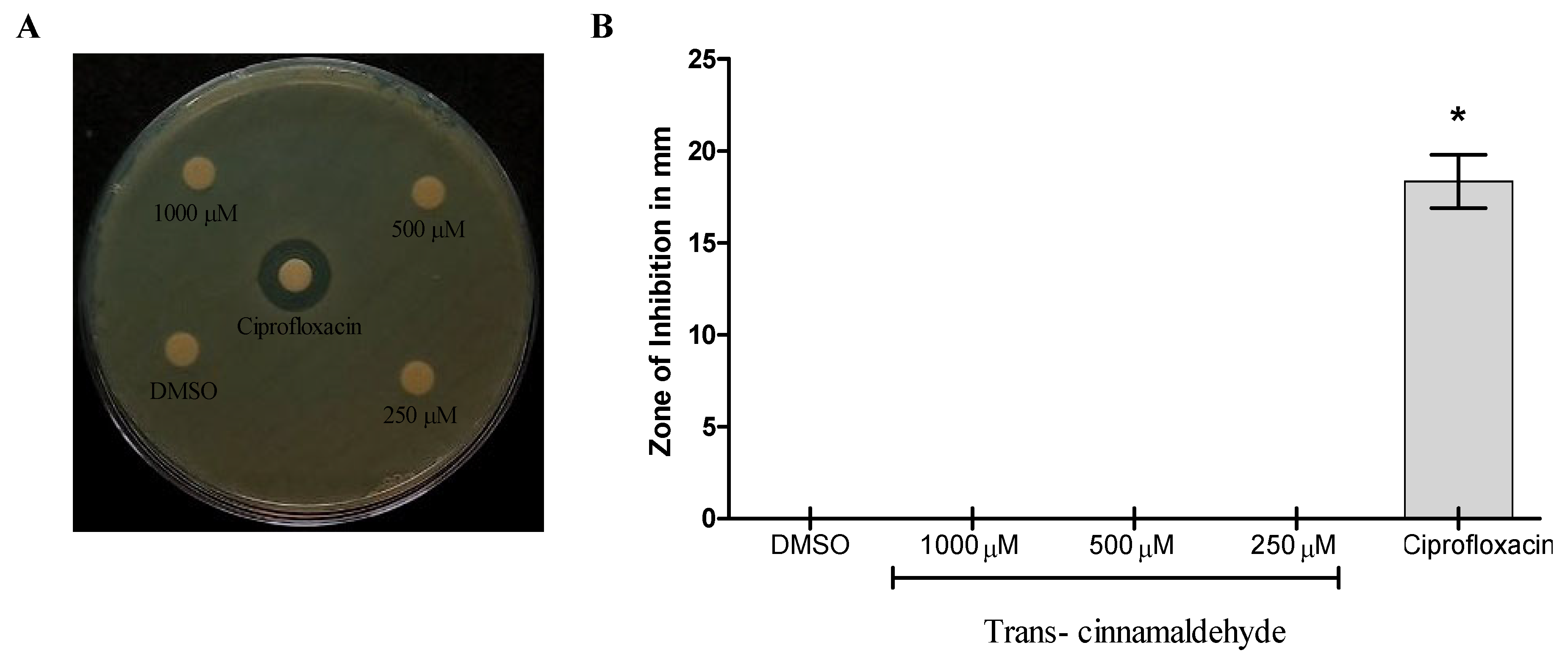

3.1. Trans-Cinnamaldehyde Antibacterial Properties Against S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa

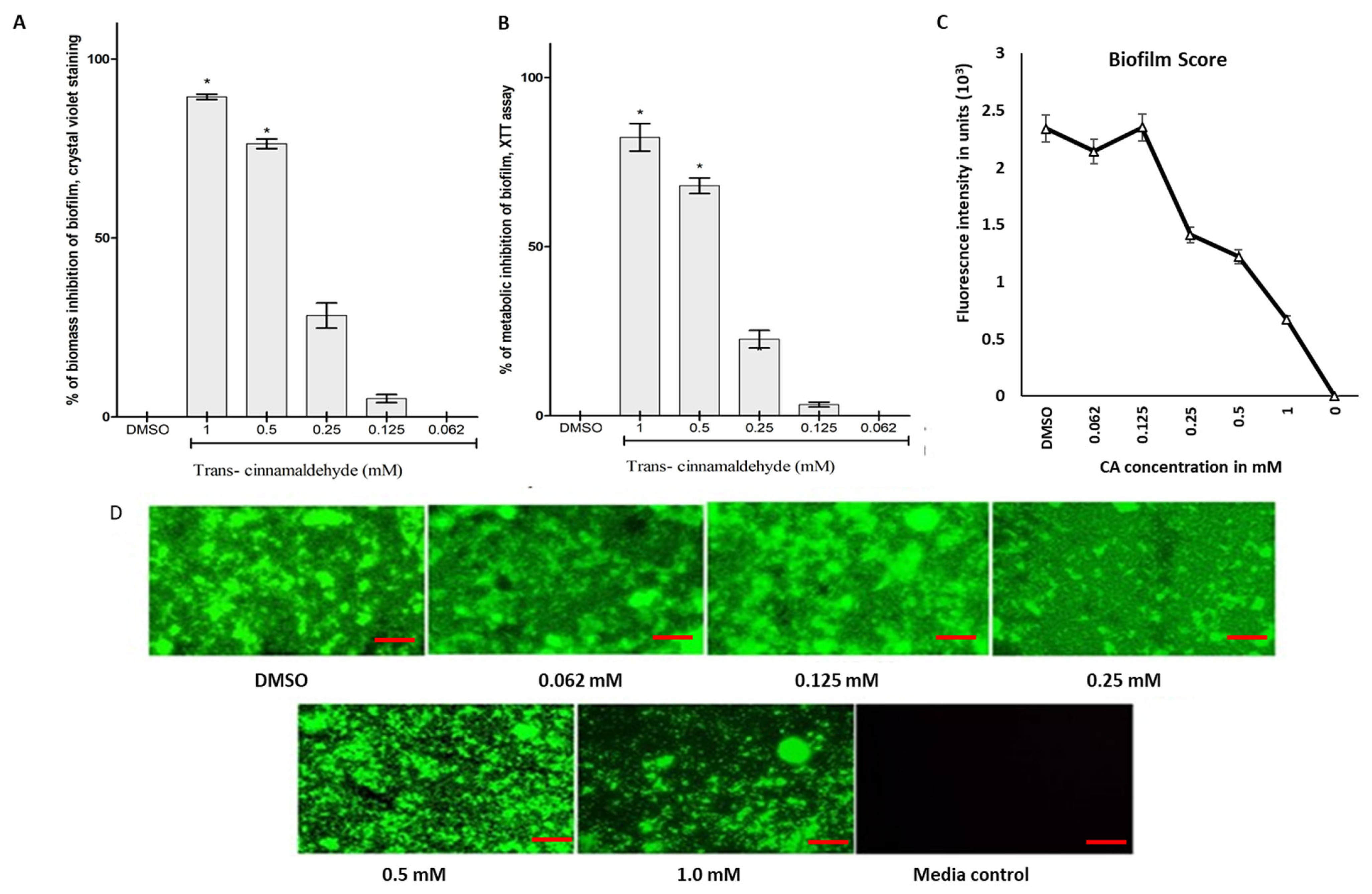

3.2. Biomass and Metabolic Inhibitory Potential of CA Against K. pneumoniae Biofilm

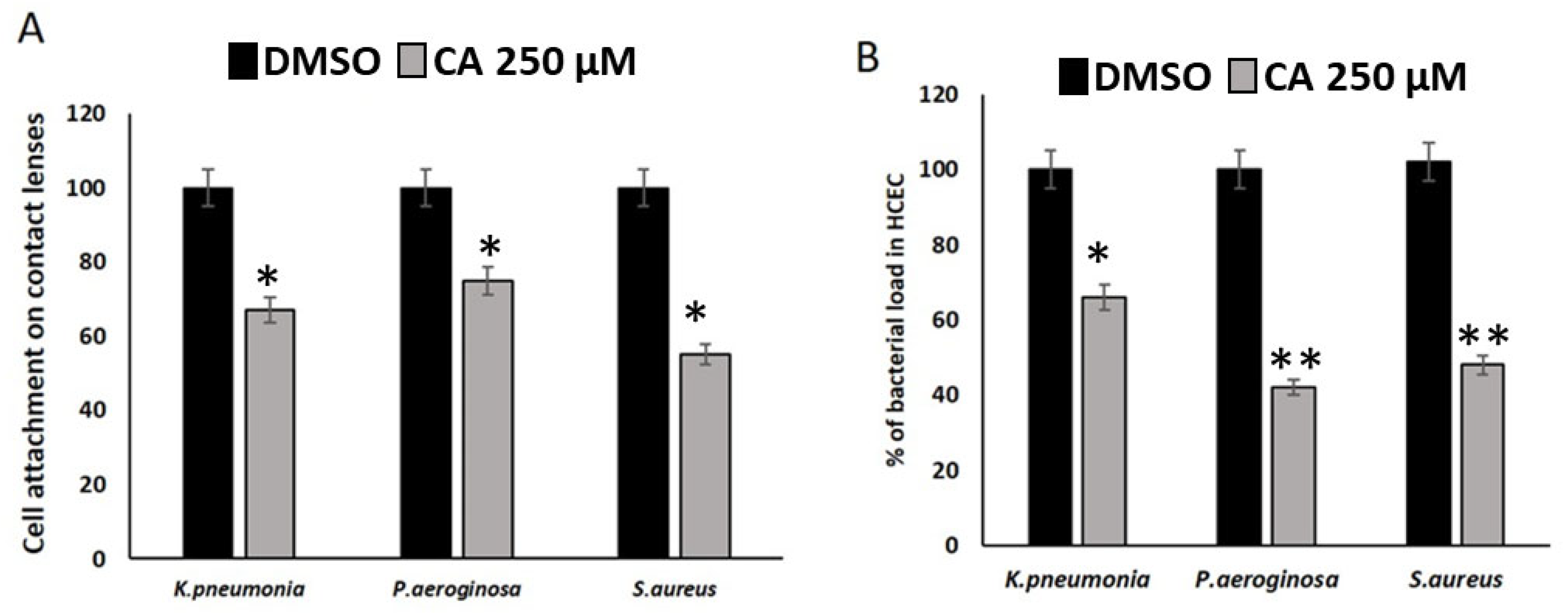

3.3. CA Inhibits the Cell Attachment and Bacterial Load of Ocular Microbes in HCEC Cell Lines

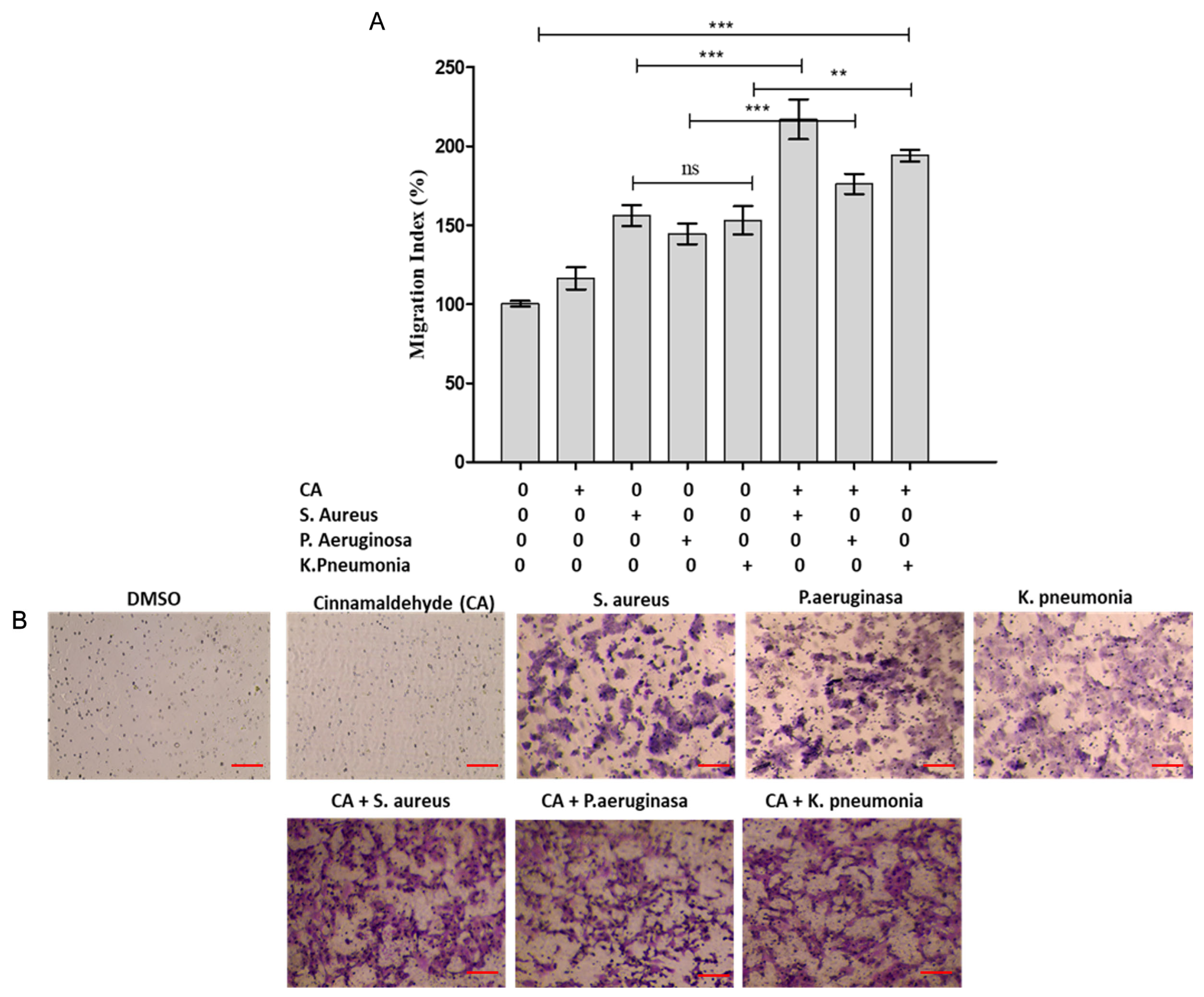

3.4. Modulation of HCEC Epithelial Cell Lines Migration Response by Cinnamaldehyde

3.5. CA Inhibited the Expression of Genes Involved in the Biofilm Formation of K. pneumoniae

3.6. Computational Docking and Interaction of mrkH with CA and C-Di-GMP

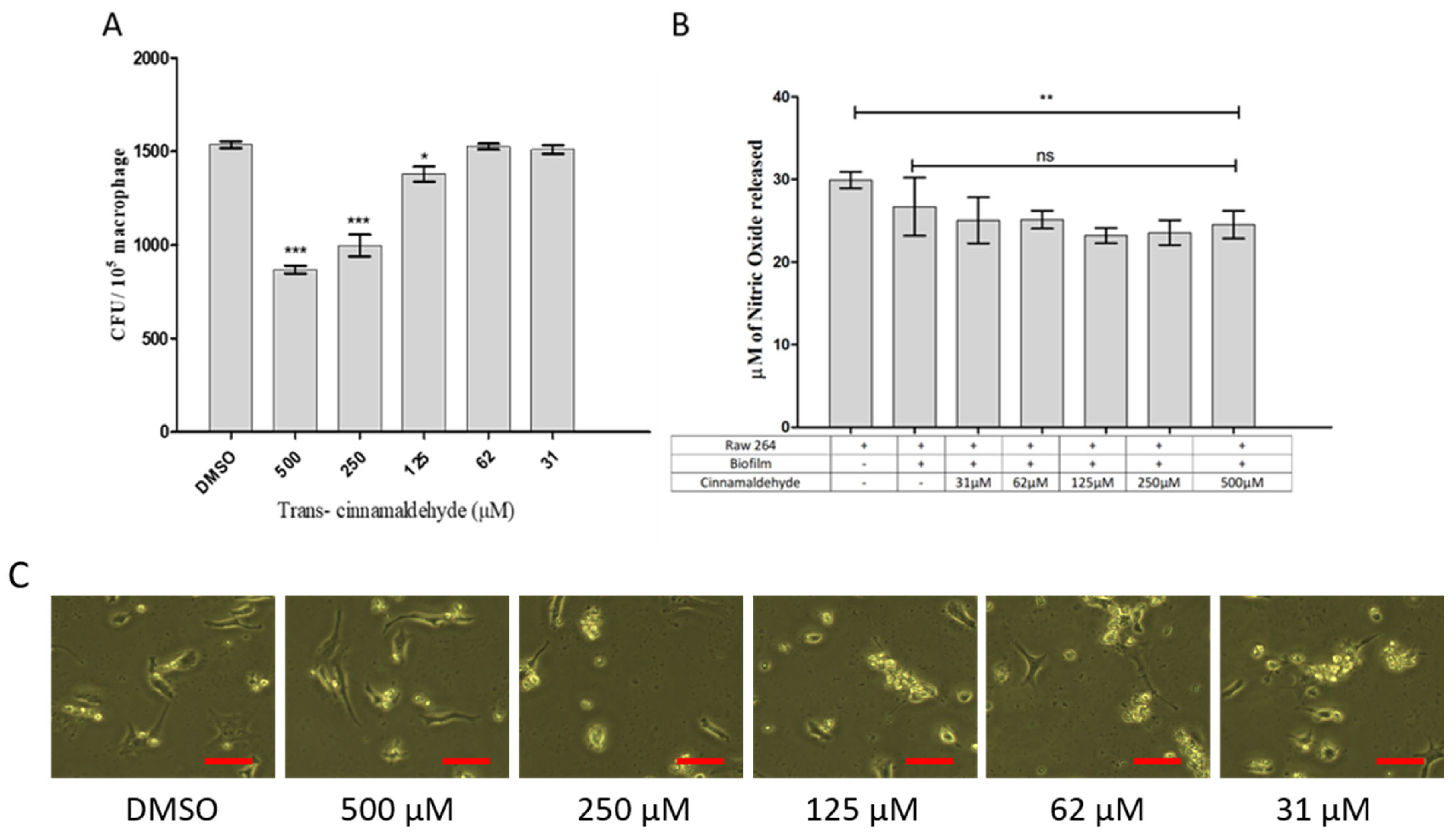

3.7. Effect of Cinnamaldehyde on Phagocytosis and Nitric Oxide Production in Rabbit Corneal Cell Lines (HCEC)

3.8. Cytokine Responses of HCEC Corneal Epithelial Cell Lines to K. pneumoniae Biofilms and CA Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, D.; Cavuoto, K.M.; Alfonso, E.C. Bacterial keratitis. In Infections of the Cornea and Conjunctiva; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Aguas, M.; Khoo, P.; Watson, S.L. Infectious keratitis: A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 50, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egrilmez, S.; Yildirim-Theveny, S. Treatment-resistant bacterial keratitis: Challenges and solutions. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, M.; Natarajan, R.; Kaur, K.; Gurnani, B. Clinical approach to corneal ulcers. TNOA J. Ophthalmic Sci. Res. 2023, 61, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.H.; Riaz, K.M.; Karamichos, D. Treatment of non-infectious corneal injury: Review of diagnostic agents, therapeutic medications, and future targets. Drugs 2022, 82, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornek, E.B.; Aydogdu, P.; Babur, E.; Cesur, S.; Ilhan, E.; Akpek, A.; Kaya, E.; Tinaz, G.B.; Sahin, A.; Bedir, T.; et al. Cinnamaldehyde- and meropenem-enriched 3D-printed corneal scaffolds for bacterial keratitis. MRS Bull. 2025, 50, 1158–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.E.S.; Destro, G.; Vieira, B.; Lima, A.S.; Ferraz, L.F.C.; Hakansson, A.P.; Darrieux, M.; Converso, T.R. Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms and their role in disease pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 877995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, L.; Acosta, I.C.; Zárate, L.; Rodríguez, P.; Huertas, M.G.; Zambrano, M.M. Biofilm and persister cell formation variability in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Colombia. Univ. Sci. 2020, 25, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, K.; Fatima, S.; Ali, A.; Ubaid, A.; Husain, F.M.; Abid, M. Biochemistry of bacterial biofilm: Insights into antibiotic resistance mechanisms and therapeutic intervention. Life 2025, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, C.T.; Cerveira, M.M.; Barboza, V.; Maria, E.; Ferrer, K.; Miller, R.G.; De Souza, T.; Zank, P.D.; Blanke, A.D.O.; Klein, V.P.; et al. A systematic review of essential oils’ antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Curr. Res. Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 6, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, H.; Shi, C.; Guo, X.; Wu, W.; Gan, C.; Li, M.; et al. Pathogenesis and treatment strategies for infectious keratitis: Exploring antibiotics, antimicrobial peptides, nanotechnology, and emerging therapies. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 15, 101250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raorane, C.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.G.; Rajasekharan, S.K.; García-Contreras, R.; Lee, J. Antibiofilm and antivirulence efficacies of flavonoids and curcumin against Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usai, F.; Di Sotto, A. trans-Cinnamaldehyde as a novel candidate to overcome bacterial resistance: An overview of in vitro studies. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Kang, O.H.; Kwon, D.Y. Trans-Cinnamaldehyde exhibits synergy with conventional antibiotic against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadha, J.; Ravi Singh, J.; Chhibber, S.; Harjai, K. Gentamicin augments the quorum quenching potential of cinnamaldehyde in vitro and protects Caenorhabditis elegans from Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 899566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshaya, B.S.; Premraj, K.; Iswarya, C.; Muthusamy, S.; Ibrahim, H.I.M.; Khalil, H.E.; Ashokkumar, V.; Vickram, S.; Kumar, V.S.; Palanisamy, S.; et al. Cinnamaldehyde inhibits Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation and promotes clearance of its colonization by modulation of phagocytes in vitro. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 181, 106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, S.S.; Cheepurupalli, L.; Gangwar, J.; Raman, T.; Ramakrishnan, J. Biofilm of Klebsiella pneumoniae minimize phagocytosis and cytokine expression by macrophage cell line. AMB Express 2022, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, R.L.I.V.; Cella, E.; Azarian, T.; Rendueles, O.; Fleeman, R.M. Diverse polysaccharide production and biofilm formation abilities of clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelusi, T.I.; Oyedele, A.Q.K.; Boyenle, I.D.; Ogunlana, A.T.; Adeyemi, R.O.; Ukachi, C.D.; Idris, M.O.; Olaoba, O.T.; Adedotun, I.O.; Kolawole, O.E.; et al. Molecular modeling in drug discovery. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2022, 29, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobiega, K.; Kraśniewska, K.; Derewiaka, D.; Gniewosz, M. Comparison of the antimicrobial activity of propolis extracts obtained by means of various extraction methods. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 5386–5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshikh, M.; Ahmed, S.; Funston, S.; Dunlop, P.; McGaw, M.; Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Resazurin-based 96-well plate microdilution method for the determination of minimum inhibitory concentration of biosurfactants. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeka, P.M.; Badger-Emeka, L.I.; Ibrahim, H.I.M.; Thirugnanasambantham, K.; Hussen, J. Inhibitory potential of mangiferin on glucansucrase producing Streptococcus mutans biofilm in dental plaque. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramenium, G.A.; Swetha, T.K.; Iyer, P.M.; Balamurugan, K.; Pandian, S.K. 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde from marine bacterium Bacillus subtilis inhibits biofilm and virulence of Candida albicans. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 207, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikrishnan, P.; Arayambath, B.; Jayaraman, V.K.; Ekambaram, K.; Ahmed, E.A.; Senthilkumar, P.; Ibrahim, H.I.M.; Sundaresan, A.; Thirugnanasambantham, K. Thidiazuron, a phenyl-urea cytokinin, inhibits ergosterol synthesis and attenuates biofilm formation of Candida albicans. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 38, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daw, K.; Baghdayan, A.S.; Awasthi, S.; Shankar, N. Biofilm and planktonic Enterococcus faecalis elicit different responses from host phagocytes in vitro. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhang, H.; Mei, L.; Dou, K.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, S.; Hasanin, M.S.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Q. Fucoidan-derived carbon dots against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm and infected dentinal tubules for the treatment of persistent endodontic infections. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanner, M.F. Python: A programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1999, 17, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, R.; Guo, J. Interactions and implications of Klebsiella pneumoniae with human immune responses and metabolic pathways: A comprehensive review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooters, K.E.; Ku, J.C.; Richter, D.M.; Krinock, M.J.; Minor, A.; Li, P.; Kim, A.; Sawyer, R.; Li, Y. Strategies for combating antibiotic resistance in bacterial biofilms. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1352273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestby, L.K.; Grønseth, T.; Simm, R.; Nesse, L.L. Bacterial biofilm and its role in the pathogenesis of disease. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio-López, J.; Lázaro-Díez, M.; Hernández-Cruz, T.M.; Blanco-Cabra, N.; Sorzabal-Bellido, I.; Arroyo-Urea, E.M.; Buetas, E.; González-Paredes, A.; Ortiz de Solórzano, C.; Burgui, S.; et al. Multimodal evaluation of drug antibacterial activity reveals cinnamaldehyde analog anti-biofilm effects against Haemophilus influenzae. Biofilm 2024, 7, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngokwe, Z.B.; Wolfoviz-Zilberman, A.; Sharon, E.; Zabrovsky, A.; Beyth, N.; Houri-Haddad, Y.; Kesler-Shvero, D. Trans-Cinnamaldehyde—Fighting Streptococcus mutans using nature. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimińska, I.; Lipska, J.; Gajewska, A.; Draszanowska, A.; Simões, M.; Olszewska, M.A. Antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of photodynamic treatment with Curcuma L. and Trans-cinnamaldehyde against Listeria monocytogenes. Molecules 2024, 29, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Yang, H.; Meng, X.; Su, R.; Cheng, S.; Wang, H.; Bai, X.; Guo, D.; Lü, X.; Xia, X.; et al. Inhibitory effects of trans-cinnamaldehyde against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2023, 20, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahrous, S.H.; El-Balkemy, F.A.; Abo-Zeid, N.Z.; El-Mekkawy, M.F.; El Damaty, H.M.; Elsohaby, I. Antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities of cinnamon oil against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from pneumonic sheep and goats. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Xiu, Z. Regulation of c-di-GMP in biofilm formation of Klebsiella pneumoniae in response to antibiotics and probiotic supernatant in a chemostat system. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yan, X.; Bai, J.; Xiang, L.; Ding, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; Liang, Q.; Zhou, Y. Identification of the BolA protein reveals a novel virulence factor in K. pneumoniae that contributes to survival in host. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00378-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubwieser, P.; Hilbe, R.; Gehrer, C.M.; Grander, M.; Brigo, N.; Hoffmann, A.; Seifert, M.; Berger, S.; Theurl, I.; Nairz, M.; et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae manipulates human macrophages to acquire iron. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1223113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.Y. The emerging problems of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections: Carbapenem resistance and biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnw219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, S.; Adaszyńska-Skwirzyńska, M.; Szewczuk, M.A.; Szczerbińska, D. Interaction between enrofloxacin and three essential oils (cinnamon bark, clove bud and lavender flower)—A study on multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli strains isolated from 1-day-old broiler chickens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Dai, J.; Xiu, Z. The inhibition mechanism of co-cultured probiotics on biofilm formation of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 135, lxae138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, M.K.; Nayak, A.K.; Hailemeskel, B.; Eyupoglu, O.E. Exploring recent updates on molecular docking: Types, method, application, limitation & future prospects. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2024, 13, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Meng, D.; Hao, N.; Wang, H.; Peng, W.; Wang, L.; Wei, Y. Yak IFNβ-3 enhances macrophage activity and attenuates Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143, 113467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, S.A.; Zhu, G.; Fanian, M.; Chen, S.; Yang, G. Exploring reduced macrophage cell toxicity of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae compared to classical Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 278, 127515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalitha, C.; Raman, T.; Rathore, S.S.; Ramar, M.; Munusamy, A.; Ramakrishnan, J. ASK2 bioactive compound inhibits MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae by antibiofilm activity, modulating macrophage cytokines and opsonophagocytosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Ferrer, S.; Peñaloza, H.F.; van der Geest, R.; Xiong, Z.; Gheware, A.; Tabary, M.; Lee, J.S. STAT1 employs myeloid cell–extrinsic mechanisms to regulate the neutrophil response and provide protection against invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae lung infection. ImmunoHorizons 2024, 8, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesur, S.; Ilhan, E.; Tut, T.A.; Kaya, E.; Dalbayrak, B.; Bosgelmez-Tinaz, G.; Arısan, E.D.; Gunduz, O.; Kijeńska-Gawrońska, E. Design of Cinnamaldehyde- and Gentamicin-Loaded Therapeutic Corneal Implants for Antibiofilm Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.M.; Zhao, Y.J.; Boekhout, T.; Wang, Q.M. Exploring the antibiofilm efficacy of cinnamaldehyde against microbial infections: In vitro and in vivo study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 130, 155542. [Google Scholar]

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| yfiN | TACGTACCGCGCTACATGAC | TCGGGCATCGGAATTGTTCA | 95 |

| mrkA | GCAAACTGGGCGTAAACTGG | CTTTCGCTTTCGGCTGAGTG | 186 |

| mrkB | ACCCGCTTTATTTATCCAGG | AAACGGGGTGGTAATGGTAT | 138 |

| mrkC | GGTATCAACGGTTCGCTGGA | CCAATGCCGCTCTGACGATA | 170 |

| mrkD | AACGTGCCGGGAATTGGTAT | GTGGTTGCCGCAGTTTTGAT | 155 |

| mrkF | AACGAAAACGCCGGGTATCT | CCTGCAAACGCACCTGATTT | 148 |

| mrkJ | CGAGCCACAGTGAGGTATCC | CCTGCGTCCATTTCGAGGTA | 96 |

| mrkH | TGGACTTTGCCGAGTT | ACCGCTATTGTCATGTTT | 120 |

| BolA | GCCATTGAGTTTGCGGTCTC | GTCGGGTGAAAAAGCAGCAG | 128 |

| ybtS | GACGGAAACAGCACGGTAAA | GAGCATAATAAGGCGAAAGA | 242 |

| 16S rRNA | GATGACCAGCCACACTGGAA | CTGCAGGGTAACGTCAATCG | 194 |

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LasL | 5′-CGTGCTCAAGTGTTCAAGG-3′ | 5′-TACAGTCGGAAAAGCCCAG-3′ | 170 |

| RHIi | 5′-TTCATCCTCCTTTAGTCTTCCC-3′ | 5′-TTCCAGCGATTCAGAGAGC-3′ | 177 |

| GAPDH | CGCTAACATCAAATGGGGTG | TTGCTGACAATCTTGAGGGAG | 201 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Khalifa, A.; Thangavelu, M.; Thirugnanasambantham, K.; Ibrahim, H.-I.M. Antibiofilm and Immunomodulatory Effects of Cinnamaldehyde in Corneal Epithelial Infection Models: Ocular Treatments Approach. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010005

Khalifa A, Thangavelu M, Thirugnanasambantham K, Ibrahim H-IM. Antibiofilm and Immunomodulatory Effects of Cinnamaldehyde in Corneal Epithelial Infection Models: Ocular Treatments Approach. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhalifa, Ashraf, Muthukumar Thangavelu, Krishnaraj Thirugnanasambantham, and Hairul-Islam M. Ibrahim. 2026. "Antibiofilm and Immunomodulatory Effects of Cinnamaldehyde in Corneal Epithelial Infection Models: Ocular Treatments Approach" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010005

APA StyleKhalifa, A., Thangavelu, M., Thirugnanasambantham, K., & Ibrahim, H.-I. M. (2026). Antibiofilm and Immunomodulatory Effects of Cinnamaldehyde in Corneal Epithelial Infection Models: Ocular Treatments Approach. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010005