Drug-Loaded Extracellular Vesicle-Based Drug Delivery: Advances, Loading Strategies, Therapeutic Applications, and Clinical Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

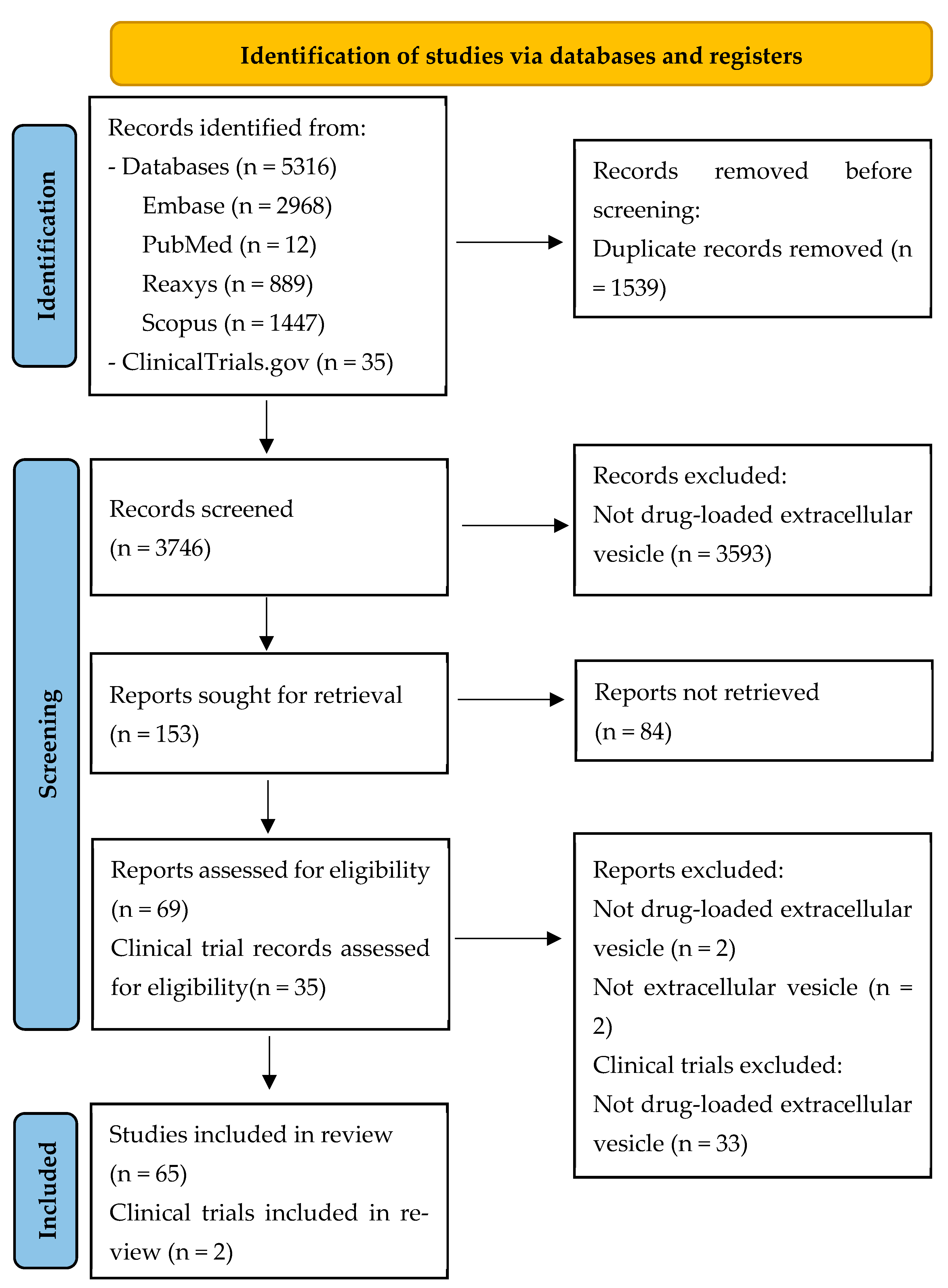

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Screening Process and Data Extraction

- Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of each study, including the type and source of EVs, type of loaded drug, particle size, targeted release of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), route of administration or drug release characteristics, and therapeutic indication.

- Table 2 presents detailed information on the type of loaded drug, loading method, loading efficiency, loading conditions (e.g., pH value, added excipients), and observed outcomes.

- Table 3 provides data on the clinical trials, including the type of vesicle, trial status, indication, loaded active ingredient, observed outcomes, and the ClinicalTrials.gov identifier (NCT number).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Overview of Included Studies

Comparative Analysis of EV Sources

| Type of EVs Source | Source of EVs | Type of Loaded Drug | Particle Size (nm) | Targeted Release of API | Administration Route/Drug Release Characteristic | Indication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) | Simvastatin | 30–150 | Alveolar bone | - - | Relapses after orthodontic tooth movement (Bone regeneration) | [35] |

| Activated T cell | Paclitaxel-poly-L-lysine prodrug | 123 ± 7 | Tumor cell | - i.v - Sustained | Triple-negative breast cancer | [23] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Rifampicin | 65–225 | Tumor cell | - i.v - Sustained | Osteosarcoma | [1] | |

| T cell | Doxorubicin | 146–147 | Tumor cell | - i.v - Sustained | Tumor treatment | [36] | |

| Non-small cell lung carcinoma A549 | Doxorubicin and lonidamine | 50–200 | Cancer cell | - i.v - Sustained | Lung cancer | [2] | |

| Endometrial mesenchymal stem cells | Atorvastatin | 50–200 | Glioblastoma tumor cell | - - | Glioblastoma | [37] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) | Doxorubicin | 169 | Tumor cell | - Intraperitoneal - Sustained | Colorectal cancer | [6] | |

| Periodontal stem cells | Aspirin | 206 | Macrophage | - Intraperitoneal - | Periodontitis | [38] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) | Baricitinib | 120 | Hair follicle | - i.v - | Alopecia areata | [24] | |

| M2-type macrophage | Berberine | 125 ± 12 | Injured spinal cord | - Intraperitoneal - Sustained | Spinal cord injury | [7] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) | Berberine | 103 | Injured spinal cord | - - Sustained | Spinal cord injury | [39] | |

| HepG2 tumor cell | Bleomycin | 105 | Tumor cell | - i.v - | Cancer | [25] | |

| Primary M2 macrophage | Curcumin | 124 | Site of inflammation | - i.v - | Spinal cord injury and rheumatoid arthritis | [8] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) | Cisplatin | 139 ± 47 | Tumor cell | - - | Cervical cancer therapy | [9] | |

| Fibroblast | Clodronate | 120 | Fibroblast | - i.v - | Pulmonary fibrosis | [40] | |

| A549 cancer cells | Docetaxel | 94–250 | Tumor cell | - i.v - | Lung cancer | [41] | |

| M1 macrophage | Docetaxel | 163 | Tumor cell | - - | Breast cancer | [42] | |

| Plasma | Donepezil | 107 | Brain | - i.v - Sustained | Alzheimer | [11] | |

| Breast cancer cell lines (4T1 and SKBR3) | Doxorubicin | 149–200 | Tumor cell | - | Retinoblastoma | [43] | |

| Endothelial cell | Doxorubicin | 50–200 | Glioma cell | - i.v - | Glioblastoma | [44] | |

| Natural killer cell | Doxorubicin | 131 | Tumor cell | - - | Triple-negative breast cancer | [45] | |

| SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells | Curcumin | 100 | Tumor cell | - - | Ovarian cancer | [21] | |

| JAWS II dendritic cell | Delphinidine | 117 ± 2 | Aortic endothelial cell | - - | Antiangiogenic | [22] | |

| Immature dendritic cells | Berberine chloride | 1106 ± 12 | Tumor cell | - - | Antitumor | [46] | |

| RAW 264.7 macrophages | Lyostaphin and vancomycin | 96 ± 6 | Liver and spleen | - i.v - Sustained | Intracellular MRSA | [47] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Rapamycin | <200 | Brain | - i.v - Sustained | Glioblastoma | [26] | |

| RAW 264.7 cells | Docetaxel | 122 ± 1 | Tumor cell | - - Sustained | Breast cancer | [48] | |

| Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | Doxorubicin | 30–200 | Bone tumor | - i.v - Sustained | Osteosarcoma | [49] | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Insulin | 153 ± 64 | Pancreatic islet | Sustained | Diabete | [12] | |

| Adipose-Derived Stem Cells | Curcumin | 50–200 | Skin flap | - i.v - | Flap grafting survival | [17] | |

| Pluripotent stem cells | Amphotericin B | Brain | - i.v - | Cryptococcal meningitis | [50] | ||

| Keratinocyte | Tofacitinib | 71 ± 3 | Keratinocytes | - - | Psoriasis | [51] | |

| Placental mesenchymal stem cells | Doxorubicin | 30–200 | Breast cancer cell | - i.v - | Breast cancer | [52] | |

| Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | Luteolin | 200 | Liver cell | - Intraperitoneal - Sustained | Liver fibrosis | [53] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Doxorubicin | 142–178 | Bone | - i.v - | Osteosarcoma | [54] | |

| Platelet | Kaempferol | 144 | Eye | - - Sustained | Corneal neovascularization | [55] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Bevacizumab | 155 ± 6 | Eye | - | Diabetic retinopathy | [56] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Rapamycin | 50–200 | Eye | - | Autoimmune Uveitis | [5] | |

| Embryonic kidney HEK293 cell | Melatonin | 100 | Skin | - | Atopic dermatitis | [57] | |

| Metastatic murine melanoma cells | Zinc-phthalocyanine | 100–200 | Tumor cell | - i.v/intratumoral - | Colon cancer | [58] | |

| Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | Gemcitabine | 60–100 | Pancreatic cell | - - | Pancreatic cancer | [59] | |

| Umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cell | Docetaxel | 218 ± 17 | Tumor cell | - - Sustained | Cancer | [60] | |

| Breast cancer cell MDA-MB-231 | Doxorubicin | 140 ± 3 | Breast cancer cell | - i.v - | Breast cancer | [61] | |

| HEK293 cells | Curcumin | 334 ± 3 | - | - -Sustained | - | [62] | |

| SF7761 stem cells-like- and U251-GMs | Doxorubicin | 100 | Glioma cell | - - | Malignant glioma | [63] | |

| Animal | Mouse BMSCs | Rifampicin | 157 ± 4 | Brain | - i.v - | Central nervous system tuberculosis | [64] |

| Milk | Anthocyanin | 106 | HepG2 cell | - | Antitumor | [65] | |

| Milk | Dexamethasone | 70 | Inflammatory cell | - - Sustained | Corneal alkali burn | [66] | |

| Mouse platelet | Resveratrol | 114 ± 8 | Injured site | - - Sustained | Promoting wound healing in diabete mice | [67] | |

| Animal milk and human mesenchymal stem cells | Doxorubicin | 114 ± 3 | Tumor cell | - - | Cancer | [68] | |

| Mouse glioma C6 cells | Cetuximab and doxorubicin | 125 ± 6 | Brain | - i.v - Sustained | Glioblastoma | [69] | |

| Mouse macrophage | Atovaquone | 84 | Tissue cyst | - i.v - | Toxoplama gondii infection | [14] | |

| Milk | Glycyrrhetinic acid | 122 ± 2 | Lung | - i.v - Sustained | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | [70] | |

| Milk | Oxaliplatin | 50–200 | Tumor cell | - i.v - Sustained | Cancer | [71] | |

| Plant | Banana | Curcumin | 50–250 | Colon | - - | Inflammatory bowel disease | [72] |

| Curcumin | Doxorubicin | 120–190 | Tumor cell | - i.v - Sustained | Cancer | [73] | |

| Grapefruit | Sodium thiosulfate | 196 ± 18 | Site of vascular calcification | - Intraperitoneal - Sustained | Vascular calcification | [74] | |

| Curcumin | Astragalus component | 154 | Tumor cell | - - Sustained | Antitumor | [75] | |

| Ginger | Curcumin | <400 | Colon | - Oral (gavage) - | Anti-colitis | [3] | |

| Plant Kaempferia parviflora | Clarithromycin | 352 ± 23 | GI tract | - - Sustained | Helicobacter pylori Infection | [4] | |

| Other | Probiotic Lactobacillus species | Doxorubicin | 142 ± 1 | Bacteria | - - Sustained | Staphylococcus species | [76] |

| Artificial cell NK cell line NK-92 | Docetaxel | 152 ± 17 | Tumor cell | - - | Lung cancer | [77] | |

| Plasma | Quercetin | 150 | Brain | - i.v - | Alzheimer | [78] | |

| Transferrin-modified SPIONs | Quercetin | 85 | Pancreatic islet | - i.v - | Type 2 diabetes | [13] |

| Type of Loaded Drug | Type of Loading | Loading Efficacy | Loading Circumstances (pH Value, Added Excipient…) | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17ß-Estradiol | Passive + active | Passive: 75 ± 4 ng/100 µg Active: 60 ± 3 ng/100 µg | - Incubation: 37 °C for 1 h - Sonication: 20% amplitude and 6 cycles of 30 s on/off for 3 min with a 2 min cooling period between each cycle | Significantly increased survival rate of BMMSCs (Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells) treated with 17β-estradiol-loaded exosomes in comparison with the control group | [20] |

| Paclitaxel-poly-L-lysine prodrug | Active | - | Membrane extrusion: 220 nm polycarbonate membrane | Mediates the synergistic effects of gene therapy and chemoimmunotherapy | [23] |

| Rifampicin | Active + passive | - | - Sonication: 20% amplitude, 6 cycles of 30 s on/off for three minutes with a two-minute cooling period between each cycle - Incubation at 37 °C for 60 min | Display potent antitumor therapeutic effects with remarkably low toxicity | [1] |

| Doxorubicin | Passive | - | Incubation in 37 °C and 50 °C water baths for 2 h | Efficient drug delivery capability in vitro and in vivo | [36] |

| Doxorubicin and lonidamine | Passive | 1 ± 0.2% and 4 ± 1.9% (Encapsulation efficiency) | Incubation overnight at 4 °C | Enhancement in anti-cancer efficacy both in vitro and in vivo | [2] |

| Atorvastatin | Active | - | Incubation along with Tween-20 | Enhanced antitumor effects compared to free atorvastatin | [37] |

| Doxorubicin (DOX) | Active | 199 ng 13% Encapsulation efficiency | Excipient: trimethylamine | The functionalization of the surface of exosomes with AS1411-DNA aptamer molecules considerably expanded the binding affinity and uptake rate in nucleolin-positive cells | [6] |

| Aspirin | Active | 0.6 μg mL−1 | Sonication: intermittent for 2 min on ice | Able to restore a certain degree of alveolar bone loss caused by periodontitis | [38] |

| Baricitinib | Active | 86 μg mL−1 | Electroporation: 125 μF, 250 V, Max capacitance, 10 pulses with a 2 s interval | Improvement of drug delivery efficiency, as well as the synergistic effect of EVs | [24] |

| Berberine | Passive + active | - | - Passive: incubation at 37 °C for 2 h - Active: sonication for 30 s in an ice bath | Accomplish the accumulation of Ber at high concentrations in the injury site | [7] |

| Berberine | Passive + active | - | - Passive: incubation at 37 °C - Active: sonication for 30 s with a 30 s pause for a small cycle, and after 3 small cycles with a 3 min pause | Decrease the level of local inflammation and the fiber extent of spinal cord injury in rats | [39] |

| Bleomycin | Passive | - | Incubation 20 min at 37 °C | Enhanced delivery of the drug to tumor cells | [25] |

| Curcumin | Active | 28% Encapsulation efficiency | Sonication | Improve motor function in inflammation models | [8] |

| Cisplatin | Passive | 32 ± 3% Loading efficiency | Incubation: 1 h at 37 °C in a water-bath shaker | Improved therapeutic efficacy in hampering cervical cancer progression both in vitro and in vivo | [9] |

| Clodronate | Active | 71 ± 3% Encapsulation efficiency | - Reverse phase evaporation method - Sonication: 30% amplitude, 30 s pulse on/off, for 2 min | Significantly enhanced pulmonary fibrotic drug delivery | [40] |

| Docetaxel | Active | 12 ± 6% Encapsulation efficiency | Electroporation: five mild electric shocks at 0.75 V in 15 s intervals | Increased drug potency compared to that of the free DTX. | [41] |

| Docetaxel | Active | 18 ± 3% Drug loading efficiency | Electroporation: 4 mm path length cuvettes | Improved the anti-cancer therapeutic efficacy with minimal side effects | [42] |

| Donepezil | Active + passive | 43 ± 0.8 Drug loading efficiency | - Sonication in Milli-Q water (250 μL) for 5 min - Incubation at 37 °C for 60 min | Higher pharmacological response, lower peripheral side effects, and without toxicity | [11] |

| Doxorubicin | Passive | 82 × 10−11 µM Dox/EV | Incubation | Display improved cellular internalization over free Dox | [43] |

| Doxorubicin | Passive | - | Oil-in-water emulsion, followed by solvent evaporation and dialysis | Facilitate penetration of anti-cancer drugs across the BBB (blood–brain barrier) and target the GBM (glioblastoma) | [44] |

| Doxorubicin | Active + passive | 51 ± 0.4% Drug loading efficiency | - Ultrasonication: 20% amplitude, six cycles of 30 sec on/off with 2 min cooling period between each cycle - Incubation at 22 °C for 120 min | Readily be engineered to target specific markers | [45] |

| Curcumin | Passive + active | Drug loading efficiency: - 10% for the incubation method - 11% for the sonication method - 9% for the freeze–thaw cycling method. | - Incubation: 1 h at 37 °C in the dark - Sonication: 6 cycles of 30 s - Freeze–thaw cycling: alternatively frozen at −70 °C and then thawed at room temperature | High stability and safety for delivery of drugs such as curcumin, but low loading efficiency of drug | [21] |

| Delphinidin | Passive | 9% Drug loading efficiency | - Mix and stir | Protect delphinidin and its metabolites from degradation | [22] |

| Berberine hydrochloride | Active + passive | 42 ± 2% Encapsulation efficiency | - Sonication for 5 min - Incubation at 37 °C for 120 min | Increase the efficacy of free BRB | [46] |

| Lyostaphin and vancomycin | Active + passive | - | - Sonication: 20% power, 10 cycles of 4 s pulse/2 s pause - Incubation at 37 °C for 60 min | Employ the mannosylated exosomes to deliver lysostaphin and vancomycin to bacterial infection sites to eradicate intracellular MRSA | [47] |

| Rapamycin | Passive | 52% Encapsulation efficiency | Incubation: 37 °C for 2.5 h | Exhibit faster and more efficient release at tumor sites | [26] |

| Docetaxel | Passive | 78% Encapsulation efficiency | Vortex | Enhancing the cellular uptake | [48] |

| Doxorubicin | Active | - | Excipient: Ammonium sulfate | Excellent antitumor properties both in vivo and in vitro | [49] |

| Insulin | Active | 50 ± 4% Drug loading efficiency | Electroporation at 200 V and 50 µF in 0.2 cm Invitrogen electroporation cuvettes | Insulin-loaded exosomes were internalized by their respective donor cells and were able to promote and enhance the transport and metabolism of glucose | [12] |

| Curcumin | Active | - | Excipient: Methanol | Enhance its duration and effect in the localization of skin flaps | [17] |

| Amphotericin B | Active + passive | - | - Co-incubation: at 37 °C for 2 h in the dark - Ultrasound: 37 kHz, 30 % power, pulse sonication for 15 min - Extrusion: 10 nm pore size - Electroporation: use the Loenza Amaxa 4D Nucleofactor | At least an eightfold increase in antifungal efficacy in vitro | [50] |

| Tofacitinib | Active + passive | - | - TFC incubation with donor cells of exosomes - TFC incubation with exosomes - Freeze–thaw cycles: frozen at −80 °C then brought back to room temperature, repeat 3 times - Probe sonication: 500 v, 2 kHz, 20% power, 6 cycles by 4 s pulse/2 s rest - Ultrasonic bath: for 20 min | Help us in diseases where communication between cells is the determining factor in the disease | [51] |

| Doxorubicin | Active | - | Ultrasonic: 20% amplitude with a 30 s on/off cycle | Significantly reduced cardiac toxicity and prolonged effectiveness | [52] |

| Luteolin | Passive + active | - Incubation: 3 ± 0.1% - Sonication: 40 ± 1% Encapsulation efficiency | - Passive: incubation at 37 °C - Active: sonication at 20% amplitude, 10 cycles of 3 s on/off for 3 min with 2 min cooling period in an ice bath between each cycle | Augmenting drug effect | [53] |

| Doxorubicin | Active | - | Excipient: triethylamine | Enhance toxicity against osteosarcoma and less toxicity in heart tissue | [54] |

| Kaempferol | Passive | 61 ± 5% Encapsulation efficiency | Mixing | Show a synergistic effect | [55] |

| Bevacizumab | Active + passive | - Freeze–thaw cycle: 61 ± 6 µg - Co-incubation at RT: 65 ± 3 µg - Saponin treatment: 74 ± 6 µg - Sonication: 61 ± 6 µg | - Freeze–thaw cycle: incubated at RT for 30 min, followed by freezing at −80 °C for 30 min; repeat 3 times - Incubation at room temperature - Incubation with 0.2% saponin - Sonication: 500 v, 2 kHz, 20% power, 4 cycles, 4 s pulse, and 2 s pause | Reduce the frequency of intravitreal injection required for treating diabetic retinopathy | [56] |

| Rapamycin | Active | - | Sonication: 25% power, 6 cycles of a 30 s pulse/30 s pause | Low risk of immunogenicity and tumorigenicity compared to cells | [5] |

| Melatonin | Passive | 97 ng/µg | Extrusion: three-step extrusion process through 10-, 5-, and 1-μm polycarbonate membrane filters | Ease of displaying targeting molecules on the surface of NVs when the cells are genetically engineered to express the targeting molecules | [57] |

| Zinc-phthalocyanine | Passive | - | Incubation | Slightly promoted the apoptosis of cancer cells | [58] |

| Gemcitabine | Active + passive | Drug loading efficiency: - 0.6 ± 0.2% for the incubation method - 4 ± 0.4% for the sonication method - 4 ± 0.5% for the electroporation method | - Electroporation: 2 mm cuvette - Ultrasonication: 20% amplitude for 30 s for three cycles with an interval of 90 s of ice cooling - Co-incubation: for 96 h | Potent cytotoxicity against pancreatic cancer cells | [59] |

| Docetaxel (DTX) | Passive + active | 9 ± 2 DTX(ng)/exosomes (μg) | - Passive: incubation for 2 h at 37 °C - Active: sonication at amplitude of 15% for 4 cycles | Superior in cytotoxicity in comparison to free DTX, with almost twice the potency | [60] |

| Doxorubicin | Active | 89 ± 2% Encapsulation efficiency | Excipient: Ammonium sulfate | The association of EVs in the lipid bilayer does not impair sensitivity to acidic pH | [61] |

| Doxorubicin | Active | - | Excipient: SF7761 GMs-derived exosome | Inhibit tumor growth in a mouse model of glioma by its delivery through the olfactory route with a nasal spray formulation | [63] |

| Rifampicin | Active | - | - Electroporation | Exhibit excellent brain targeting ability in vitro and vivo | [64] |

| Anthocyanin (ACN) | Active + passive | - | - Ultrasonic - Electroporation - Saponin - Incubation - Freeze–thaw cycles | The formulation prepared using the ultrasonic method can effectively enhance the stability of ACN | [65] |

| Dexamethasone | Active | - | Ultrasonication | Increased targeting affinity for macrophages | [66] |

| Resveratrol | Passive | - | Incubation: 37 °C for 1 h | Can be used as wound dressing for sustained drug release | [67] |

| Doxorubicin | Passive + active | - | - Incubation: 37 °C for 2 h - Electroporation: using a Neon™ Transfection System - Sonication: 20% amplitude, and 6 cycles of 30 s on/off for 4 min with a 2 min cooling period between each cycle | With electroporation, greatest success was reached in loading Dox into the EVs and minimal negative effects on surface proteins were detected, while sonication seemed to be detrimental to these proteins | [68] |

| Cetuximab | Passive | - | Incubation: 40 °C for 2 h | Synergistically deliver antibodies and drugs into the brain via intravenous administration | [69] |

| Atovaquone | Passive | 57 ± 6% Encapsulation efficiency | Incubation: 12 h at room temperature under stirring | Elicit potent anti-toxoplasmosis activity | |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid | Passive | 9% Drug loading efficiency | - Co-incubation: 37 °C for 1 h | Enhance lung function recovery | [70] |

| Oxaliplatin | Passive | - | - Incubation: 12 h at 4 °C | Have a high potential for treating solid tumor | [71] |

| Curcumin | Active | - | - pH-driven method: pH = 12 | Increase the bioavailability of hydrophobic drugs | [72] |

| Doxorubicin | Passive | 38 ± 2% Drug loading capacity | - Co-incubation: Curcuma and doxorubicin in 1:1 ratio at 37 °C and 200 rpm for 2 h | The nanoparticles exhibit excellent stability and controlled drug release properties | [73] |

| Sodium thiosulfate | Passive | - | Incubation at room temperature for 24 h | The nanodrugs exhibit excellent cellular uptake capacity | [74] |

| Astragalus component | Active | 34% Encapsulation efficiency | Sonication: 50 Hz, 30 min, 100% | Enhancement of synergistic antitumor activity. | [75] |

| Curcumin | Active + passive | 89± 0.3% Encapsulation efficiency | - Ultrasound: 20% amplitude for 1 min per cycle - Incubation: 37 °C for 1 h | Shows better anti-ulcerative colitis activity than either free curcumin or ginger-derived nanovesicles | [3] |

| Clarithromycin (CLA) | Passive | 92 ± 4% Encapsulation efficiency | Incubation at room temperature for 1 h on a rotator | KPEVs-CLA (Kaempferia parviflora extracellular vesicles) showed superior anti-inflammatory activity | [4] |

| Doxorubicin (DOX) | Passive + active | Encapsulation efficiency: - Shaking: 58 ± 4% - Electroporation: 63 ± 6% - Sonication: 72 ± 5% | - Shaking: 200 rpm and 37 °C for 4 h - Electroporation: single pulse of 1.8 kV - Sonication: 120 W, 30 kHz, 20% amplitude, and 30 cycles of 2 s interval on/off time | DOXLEV(lactic acid bacteria-derived Evs) exhibited enhanced antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus species compared to DOXfree | [76] |

| Docetaxel (DTX) | Active | 1% Encapsulation efficiency | Extrusion: 100 μg/mL of Docetaxel is added prior to extrusion | Increase the efficacy of DTX | [77] |

| Quercetin | Passive | 30 ± 8% Encapsulation efficiency | Incubation: continuous shaking at 4 °C overnight | Enhance the bioavailability of Quercetin | [78] |

| Quercetin | Passive | - | Incubation for 8 h at 4 °C | Better stability and higher solubility | [13] |

| Curcumin | Passive | - | Incubation for 30 min, at 37 °C, at neutral pH with shaking | Effective EV–curcumin delivery system with good stability, release control, and cytocompatibility | [62] |

| Type of Vesicle | State of Clinical | Condition | Loading Active | Outcome | NCT Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exosome | Completed | Male pattern baldness | Ecklonia cava (brown seaweed) Thuja orientalis (medicinal plant) | Inclusion criteria: - Malaysian men aged 20–50 - Diagnosed with Norwood Grade 2–3 androgenic alopecia Exclusion criteria: - Have thyroid issues, bleeding disorders, or diabetes - Use medical hair treatments, steroids, or immunosuppressants - Have Norwood Grades 1, 4–7, or cicatricial alopecia - Smokers Result: hair density and thickness improvements with minimal reported side effects | NCT06930326 [19] |

| Plant Exosomes | Completed | Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Curcumin | Inclusion criteria: - Confirmed diagnosis of IBD (either CD or UC) with moderate disease - Age 18 years or older - All sexes eligible Exclusion criteria: - Pregnant, HIV-positive individuals - Use of immunosuppressive drugs (unless for IBD treatment) - Active cancer within the past 5 years - Ginger allergy Result: after 30 days - Decrease in inflammatory cells in the biopsy after treatment versus before treatment - Decrease in subjective symptoms | NCT04879810 [18] |

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms of Action: A Three-Step Cellular Uptake Framework

4.1.1. Step 1—Cellular Uptake

4.1.2. Step 2—Endosomal Escape and Cargo Release

4.1.3. Step 3—Cargo Targeting and Functional Engagement

4.2. Advantages and Limitations of EV-Based Drug Delivery

4.3. Disease-Specific Pathophysiological Targeting of Drug-Loaded EVs

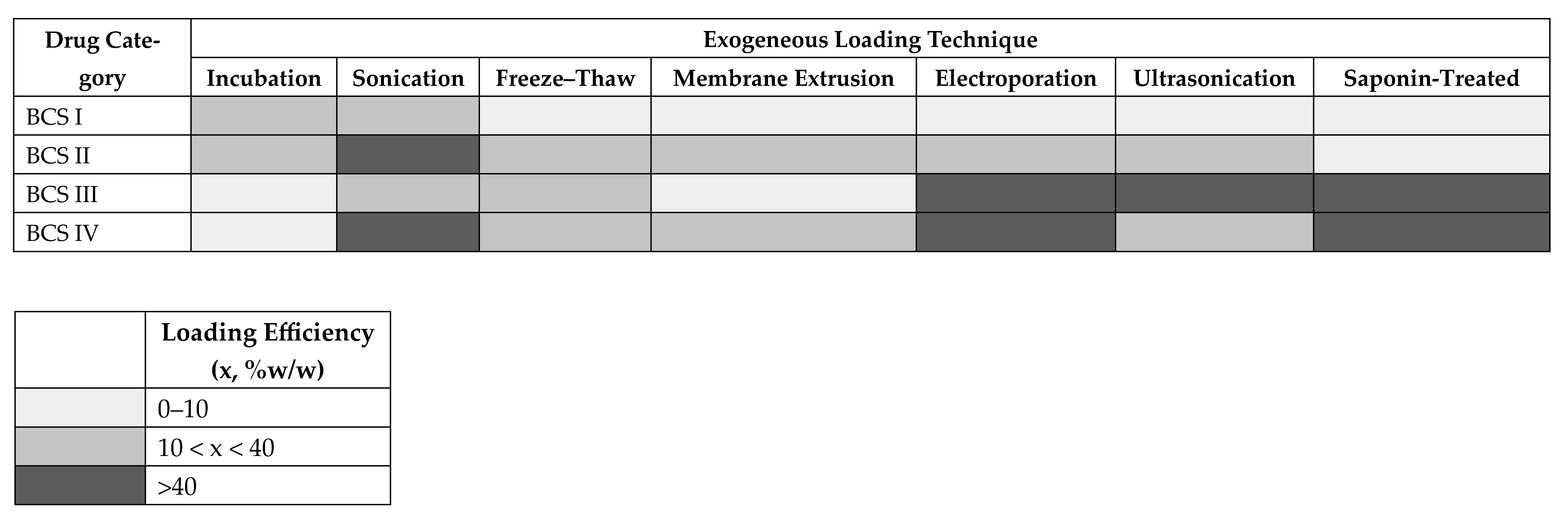

4.4. Loading Method Preferences and Trade-Offs

| BCS Class | Representative Drug | Preferred Loading Techniques | Observed Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I (High solubility, High permeability) | Estradiol [1], Aspirin [8], Delphinidin [36] | Incubation (passive), mild sonication | Estradiol: passive ~75 ng/100 µg vs. active ~60 ng/100 µg (incubation > sonication). Aspirin: low efficiency with sonication (0.587 µg/mL). Delphinidin: 9% with passive incubation. Overall: gentle methods sufficient, but efficiency is modest. |

| Class II (Low solubility, High permeability) | Curcumin [14,20,67,71], Berberine [11,12,37], Atorvastatin [6], Docetaxel [21,23,40,55,74], Paclitaxel [2] | Passive incubation, sonication, extrusion | Curcumin: 10% (incubation), 11% (sonication), 9% (freeze–thaw). Berberine: variable efficiency with passive + sonication (up to ~40%). Docetaxel: 12–18% with electroporation; ~77% with passive vortexing; very low (1.3%) with extrusion. Lipophilic drugs load well but are technique-dependent |

| Class III(High solubility, Low permeability) | Doxorubicin [4,5,7,24,25,26,41,46,48,56,57,62,68,73], Cisplatin [17], Insulin [42], Baricitinib [9] | Electroporation, ultrasonication, saponin, freeze–thaw | Doxorubicin: encapsulation efficiency ranged from <1% to ~89%, depending on method and excipients. Cisplatin: ~32% with incubation. Insulin: ~50% with electroporation. Baricitinib: 86 µg/mL with electroporation. Active methods clearly outperform passive incubation for hydrophilic/charged molecules. |

| Class IV(Low solubility, Low permeability; large/complex molecules) | Rapamycin [39,51], Amphotericin B [44], Bevacizumab (mAb) [50], Kaempferol [49], Luteolin [47] | Sonication, electroporation, saponin, freeze–thaw, extrusion | Bevacizumab: freeze–thaw (61 µg), co-incubation (65 µg), saponin (74 µg), sonication (61 µg). Luteolin: passive 3%, sonication 40%. Amphotericin B: large gains with active approaches (sonication, extrusion, electroporation). These complex/larger molecules require aggressive methods, with clear trade-offs in EV integrity. |

4.5. Clinical Translation and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EVs | Extracellular Vesicles |

References

- Chen, W.; Lin, W.; Yu, N.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Gong, F.; Li, N.; Chen, X.; et al. Activation of Dynamin-Related Protein 1 and Induction of Mitochondrial Apoptosis by Exosome-Rifampicin Nanoparticles Exerts Anti-Osteosarcoma Effect. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 5431–5446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, W.; Li, F.; Zeng, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Weng, J.; Li, Z.; Sun, L. Amplification of anticancer efficacy by co-delivery of doxorubicin and lonidamine with extracellular vesicles. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Pei, J.; Zhou, Z.; Lei, P.; Wang, M.; Zhang, P.; Yu, H.; Fan, G.; et al. Formulation, characterization, and evaluation of curcumin-loaded ginger-derived nanovesicles for anti-colitis activity. J. Pharm. Anal. 2024, 14, 101014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemidkanam, V.; Banlunara, W.; Chaichanawongsaroj, N. Kaempferia parviflora Extracellular Vesicle Loaded with Clarithromycin for the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 1967–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Su, L.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, H.; An, J.; Ni, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Therapeutic Effect of Rapamycin-Loaded Small Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 864956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, N.F.; Amini, R.; Ramezani, M.; Saidijam, M.; Hashemi, S.M.; Najafi, R. AS1411 aptamer-functionalized exosomes in the targeted delivery of doxorubicin in fighting colorectal cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 155, 113690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.-S.; Zhang, C.-J.; Xia, N.; Tian, H.; Li, D.-Y.; Lin, J.-Q.; Mei, X.-F.; Wu, C. Berberine-loaded M2 macrophage-derived exosomes for spinal cord injury therapy. Acta Biomater. 2021, 126, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Li, H.; Han, B.; Deng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, X. Cell penetrating peptide modified M2 macrophage derived exosomes treat spinal cord injury and rheumatoid arthritis by loading curcumin. Mater. Des. 2023, 225, 111455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Liu, T.; Miao, L.; Ji, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X. Cisplatin-encapsulated TRAIL-engineered exosomes from human chorion-derived MSCs for targeted cervical cancer therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jin, Z.; Fu, T.; Qian, Y.; Bian, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Drug Delivery Systems in Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.O.; Counil, H.; Rabanel, J.-M.; Haddad, M.; Zaouter, C.; Khedher, M.R.f.B.; Patten, S.A.; Ramassamy, C. Donepezil-Loaded Nanocarriers for the Treatment of Alzheimer?s Disease: Superior Efficacy of Extracellular Vesicles Over Polymeric Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 1077–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Morales, B.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; González-Valdez, J. Exosome-mediated insulin delivery for the potential treatment of diabetes mellitus. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Rao, L.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, S.; Xia, H.; Yang, J.; Lv, X.; Qin, D.; Zhu, C. Controlled SPION-Exosomes Loaded with Quercetin Preserves Pancreatic Beta Cell Survival and Function in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 5733–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudarzi, F.; Jajarmi, V.; Shojaee, S.; Mohebali, M.; Keshavarz, H. Formulation and evaluation of atovaquone-loaded macrophage-derived exosomes against Toxoplasma gondii: In vitro and in vivo assessment. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0308023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, C.; Amirsaadat, S.; Jalil, A.T.; Kadhim, M.M.; Abasi, M.; Pilehvar, Y. Curcumin-Loaded Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Derived Exosomes Efficiently Attenuate Proliferation and Inflammatory Response in Rheumatoid Arthritis Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Gu, Z. Extracellular vesicle as a next-generation drug delivery platform for rheumatoid arthritis therapy. J. Control. Release 2025, 381, 113610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Lei, L.; Yang, P.; Ju, Y.; Fan, X.; Fang, B. Exosomes-carried curcumin based on polysaccharide hydrogel promote flap survival. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04879810 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06930326 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Farashah, M.S.G.; Javadi, M.; Rad, J.S.; Shakouri, S.K.; Asnaashari, S.; Dastmalchi, S.; Nikzad, S.; Roshangar, L. 17β-Estradiol-Loaded Exosomes for Targeted Drug Delivery in Osteoporosis: A Comparative Study of Two Loading Methods. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 13, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramezani, R.; Sajadi, H.M.; Babashah, S. The effect of curcumin-loaded exosomes on the proliferation of human ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkallah, M.; Nzoughet-Kouassi, J.; Simard, G.; Thoulouze, L.; Marze, S.; Ropers, M.H.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Enhancement of the anti-angiogenic effects of delphinidin when encapsulated within small extracellular vesicles. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shen, M.; Wan, X.; Sheng, L.; He, Y.; Xu, M.; Yuan, M.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, J. Activated T cell-derived exosomes for targeted delivery of AXL-siRNA loaded paclitaxel-poly-L-lysine prodrug to overcome drug resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, F.; Yang, R.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, B. Baricitinib-loaded EVs promote alopecia areata mouse hair regrowth by reducing JAK-STAT-mediated inflammation and promoting hair follicle regeneration. Drug Discov. Ther. 2024, 18, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Younis, M.; Yingying, S.; Tanziela, T.; Yuan, L. Bleomycin loaded exosomes enhanced antitumor therapeutic efficacy and reduced toxicity. Life Sci. 2023, 330, 121977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.L.; Tang, Y.P.; Qu, Y.Q.; Yun, Y.X.; Zhang, R.L.; Wang, C.R.; Wong, V.K.W.; Wang, H.M.; Liu, M.H.; Qu, L.Q.; et al. Exosomal delivery of rapamycin modulates blood-brain barrier penetration and VEGF axis in glioblastoma. J. Control. Release 2025, 381, 113605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; He, C.; Hao, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Zhu, G. Prospects and challenges of extracellular vesicle-based drug delivery system: Considering cell source. Drug Deliv. 2020, 27, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Jin, J.; Fu, Z.; Wang, G.; Lei, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, J. Extracellular vesicle-based drug overview: Research landscape, quality control and nonclinical evaluation strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.; O’Driscoll, L.; Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W. MISEV2023: An updated guide to EV research and applications. J Extracell Vesicles 2024, 13, e12416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kul, E.; Okoroafor, U.; Dougherty, A.; Palkovic, L.; Li, H.; Valiño-Ramos, P.; Aberman, L.; Young, S.M., Jr. Development of adenoviral vectors that transduce Purkinje cells and other cerebellar cell-types in the cerebellum of a humanized mouse model. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2024, 32, 101243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, P.H.; Xiang, D.; Nguyen, T.N.; Tran, T.T.; Chen, Q.; Yin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, L.; Duan, A.; Chen, K.; et al. Aptamer-guided extracellular vesicle theranostics in oncology. Theranostics 2020, 10, 3849–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Vader, P.; Schiffelers, R.M. Extracellular vesicles for nucleic acid delivery: Progress and prospects for safe RNA-based gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2017, 24, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, A.; Rubinstein, A.; Kudryavtsev, I.; Yakovlev, A.; Golovkin, A. Extracellular vesicles as the drug delivery vehicle for gene-based therapy. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2025, 12, 041301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.G.; Shah, K.; Cromer, B.; Sumer, H. Comparative analysis of extracellular vesicles isolated from human mesenchymal stem cells by different isolation methods and visualisation of their uptake. Exp. Cell Res. 2022, 414, 113097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Muhammed, F.K.; Liu, Y. Simvastatin encapsulated in exosomes can enhance its inhibition of relapse after or-thodontic tooth movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2022, 162, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qiao, C.; Kong, X.; Yang, J.; Guo, F.; Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Xiu, H.; He, Y.; et al. Adhesion between EVs and tumor cells facilitated EV-encapsulated doxorubicin delivery via ICAM1. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 205, 107244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valipour, E.; Ranjbar, F.E.; Mousavi, M.; Ai, J.; Malekshahi, Z.V.; Mokhberian, N.; Taghdiri-Nooshabadi, Z.; Khanmohammadi, M.; Nooshabadi, V.T. The anti-angiogenic effect of atorvastatin loaded exosomes on glioblastoma tumor cells: An in vitro 3D culture model. Microvasc. Res. 2022, 143, 104385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, R.; Da, N.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, B.; He, X. Aspirin loaded extracellular vesicles inhibit inflammation of macrophages via switching metabolic phenotype in periodontitis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 667, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhao, Y.L.; Xu, T.; Yang, C.W.; Chen, X.Q. Berberine-loaded MSC-derived sEVs encapsulated in injectable GelMA hydrogel for spinal cord injury repair. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 643, 123283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Fan, M.; Huang, D.; Li, B.; Xu, R.; Gao, F.; Chen, Y. Clodronate-loaded liposomal and fibroblast-derived exosomal hybrid system for enhanced drug delivery to pulmonary fibrosis. Biomaterials 2021, 271, 120761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, M.; Lin, D.; Liang, D.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Y. Docetaxel-loaded exosomes for targeting non-small cell lung cancer: Preparation and evaluation in vitro and in vivo. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 1510–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, H.; Liu, T. Docetaxel-loaded M1 macrophage-derived exosomes for a safe and efficient chemoimmunotherapy of breast cancer. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, W.; Yeung, V.; Kahale, F.; Parekh, M.; Cortinas, J.; Chen, L.; Ross, A.E.; Ciolino, J.B. Doxorubicin-Loaded Extracellular Vesicles Enhance Tumor Cell Death in Retinoblastoma. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Song, J.; Lou, L.; Qi, X.; Zhao, L.; Fan, B.; Sun, G.; Lv, Z.; Fan, Z.; Jiao, B.; et al. Doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticle coated with endothelial cells-derived exosomes for immunogenic chemotherapy of glioblastoma. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2021, 6, e10203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, Z.S.; Ghavami, M.; Mohammadi, F.; Shokrollahi Barough, M.; Shokati, F.; Asghari, S.; Khalili, S.; Akbari Yekta, M.; Ghavamzadeh, A.; Forooshani, R.S. Doxorubicin-loaded NK exosomes enable cytotoxicity against triple-negative breast cancer spheroids. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2024, 27, 1604–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salek, A.; Selmi, M.; Barboura, M.; Martinez, M.C.; Chekir-Ghedira, L.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Enhancement of the In Vitro Antitumor Effects of Berberine Chloride When Encapsulated within Small Extracellular Vesicles. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Xie, B.; Peng, H.; Shi, G.; Sreenivas, B.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; He, Y. Eradicating intracellular MRSA via targeted delivery of lysostaphin and vancomycin with mannose-modified exosomes. J. Control. Release 2021, 329, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, M.; Kulkarni, M.; Narisepalli, S.; Chitkara, D.; Mittal, A. Exosomal fragment enclosed polyamine-salt nano-complex for co-delivery of docetaxel and mir-34a exhibits higher cytotoxicity and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, M.; Jin, L.; Guo, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhanghuang, C.; Tan, X.; Mi, T.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; et al. Exosome mimetics derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells deliver doxorubicin to osteosarcoma in vitro and in vivo. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 3291–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fang, W.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, G.; Gu, J. iPSC-derived exosomes as amphotericin B carriers: A promising approach to combat cryptococcal meningitis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1531425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, P.; Varshosaz, J.; Mirian, M.; Minaiyan, M.; Kazemi, M.; Bodaghi, M. Keratinocyte Exosomes for Topical Delivery of Tofacitinib in Treatment of Psoriasis: An In Vitro/ In Vivo Study in Animal Model of Psoriasis. Pharm. Res. 2024, 41, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, X. Key Magnetized Exosomes for Effective Targeted Delivery of Doxorubicin Against Breast Cancer Cell Types in Mice Model. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 10711–10724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashour, A.A.; El-Kamel, A.H.; Mehanna, R.A.; Mourad, G.; Heikal, L. Luteolin-loaded exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: A promising therapy for liver fibrosis. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 3270–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Chen, F.; Chen, J.; Lin, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Lin, J.; Zhong, G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Exosomes as Nanodrug Carrier of Doxorubicin for Targeted Osteosarcoma Therapy via SDF1-CXCR4 Axis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 3483–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.-S.; Chen, H.-A.; Chang, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-J.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Widhibrata, A.; Yang, Y.-H.; Hsieh, E.-H.; Delila, L.; Lin, I.C.; et al. Platelet-derived extracellular vesicle drug delivery system loaded with kaempferol for treating corneal neovascularization. Biomaterials 2025, 319, 123205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.K.; Ballal, A.R.; Shailaja, S.; Seetharam, R.N.; Raghu, C.H.; Sankhe, R.; Pai, K.; Tender, T.; Mathew, M.; Aroor, A.; et al. Small extracellular vesicle-loaded bevacizumab reduces the frequency of intravitreal injection required for diabetic retinopathy. Theranostics 2023, 13, 2241–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Go, G.; Yun, C.-W.; Yea, J.-H.; Yoon, S.; Han, S.-Y.; Lee, G.; Lee, M.-Y.; Lee, S.H. Topical administration of melatonin-loaded extracellular vesicle-mimetic nanovesicles improves 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, P.; Huis; T Veld, R.V.; Jorquera-Cordero, C.; Chan, A.B.; Ossendorp, F.; Cruz, L.J. Zinc-phthalocyanine-loaded extracellular vesicles increase efficacy and selectivity of photodynamic therapy in co-culture and preclinical models of colon cancer. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.G.; Chen, T.M.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.C.; Kong, Y. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes loaded with gemcitabine inhibit pancreatic cancer cell proliferation by enhancing apoptosis. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 16, 4006–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, M.; Sahoo, B.; Chaudhary, D.K.; Narisepalli, S.; Tiwari, S.; Chitkara, D.; Mittal, A. Human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes as an efficient nanocarrier for Docetaxel and miR-125a: Formulation optimization and anti-metastatic behaviour. Life Sci. 2023, 322, 121621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.M.P.; Gomes, E.R.; de Barros, A.L.B.; Cassali, G.D.; de Carvalho, A.T.; Silva, J.d.O.; Pádua, A.L.; Oliveira, M.C. Hybrid Nanosystem Formed by DOX-Loaded Liposomes and Extracellular Vesicles from MDA-MB-231 Is Effective against Breast Cancer Cells with Different Molecular Profiles. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazsoki, A.; Németh, K.; Visnovitz, T.; Lenzinger, D.; I Buzás, E.; Zelkó, R. Formulation and characterization of nanofibrous scaffolds incorporating extracellular vesicles loaded with curcumin. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Sidu, R.K.; Zou, H.; Alam, M.K.; Yang, M.; Lee, Y. Inhibition of Glioma Cells’ proliferation by doxorubicin-loaded Exosomes via microfluidics. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 8331–8343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ding, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, R.; Hu, C.; Tang, Q.; An, Y. Angiopep-2 Modified Exosomes Load Rifampicin with Potential for Treating Central Nervous System Tuberculosis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Si, X.; Cui, H.; Li, J.; Bao, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, B. Anthocyanin-loaded milk-derived extracellular vesicles nano-delivery system: Stability, mucus layer penetration, and pro-oxidant effect on HepG2 cells. Food Chem. 2024, 458, 140152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Ye, Y.; Fan, K.; Chen, C.; Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Dong, C.; Li, C.; Dong, N. Anti-inflammatory and Restorative effects of milk exosomes and Dexamethasone-Loaded exosomes in a corneal alkali burn model. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 666, 124784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Dong, Y.; Xu, P.; Pan, Q.; Jia, K.; Jin, P.; Zhou, M.; Xu, Y.; Guo, R.; Cheng, B. A composite hydrogel containing resveratrol-laden nanoparticles and platelet-derived extracellular vesicles promotes wound healing in diabetic mice. Acta Biomater. 2022, 154, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhya, A.; Tsiapalis, D.; McNamee, N.; Talbot, B.; O’driscoll, L. Doxorubicin Loading into Milk and Mesenchymal Stem Cells? Extracellular Vesicles as Drug Delivery Vehicles. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, A.; Sun, Y.; Duan, X.; Li, N.; Xia, H.; Liu, W.; Sun, K. Exosome-mediated delivery platform of biomacromolecules into the brain: Cetuximab in combination with doxorubicin for glioblastoma therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 660, 124262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, B.; Ren, X.; Lin, X.; Teng, Y.; Xin, F.; Ma, W.; Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; et al. Glycyrrhetinic acid loaded in milk-derived extracellular vesicles for inhalation therapy of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Control. Release 2024, 370, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go, G.; Park, H.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yun, C.W.; Lee, S.H. Inhibitory Effect of Oxaliplatin-loaded Engineered Milk Extracellular Vesicles on Tumor Progression. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Peng, S.; Zhou, L.; McClements, D.J.; Fang, S.; Liu, W. Colonic delivery and controlled release of curcumin encapsulated within plant-based extracellular vesicles loaded into hydrogel beads. Food Res. Int. 2025, 202, 115540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Li, G.; Pan, J.; Dou, D.; Ma, K.; Cui, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, X. Antibody functionalized curcuma-derived extracellular vesicles loaded with doxorubicin overcome therapy-induced senescence and enhance chemotherapy. J. Control. Release 2025, 379, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Teng, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, P.; Chen, G.; Wang, C.; Liang, X.-J.; Ou, C. Biomimetic Grapefruit-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Safe and Targeted Delivery of Sodium Thiosulfate against Vascular Calcification. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 24773–24789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.-e.; Zheng, Y.; He, Y.; Pan, J.; Liu, N.; Xu, Y.; Ma, R.; Zhai, J.; et al. Curcumae Rhizoma Exosomes-like nanoparticles loaded Astragalus components improve the absorption and enhance anti-tumor effect. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 81, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Cho, H.; Kim, K.-S. Antibiotic-loaded Lactobacillus-derived extracellular vesicles enhance the bactericidal efficacy against Staphylococcus species. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 105, 106607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Rojas, J.; Zavala, G.; Contreras-Lopez, R.; Olivares, B.; Aarsund, M.; Inngjerdingen, M.; Nyman, T.A.; Sandoval, F.I.; Ramírez, O.; Alarcón-Moyano, J.; et al. Artificial cell-derived vesicles by extrusion, a novel docetaxel drug delivery system for lung cancer. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 106, 106693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Guo, L.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Sui, H.; Zhao, L. Brain delivery of quercetin-loaded exosomes improved cognitive function in AD mice by inhibiting phosphorylated tau-mediated neurofibrillary tangles. Drug Deliv. 2020, 27, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklander, O.P.B.; Brennan, M.; Lötvall, J.; Breakefield, X.O.; El Andaloussi, S. Advances in therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kink, J.A.; Bellio, M.A.; Forsberg, M.H.; Lobo, A.; Thickens, A.S.; Lewis, B.M.; Ong, I.M.; Khan, A.; Capitini, C.M.; Hematti, P. Large-scale bioreactor production of extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stromal cells for treatment of acute radiation syndrome. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dieu, L.L.; Kazsoki, A.; Zelkó, R. Drug-Loaded Extracellular Vesicle-Based Drug Delivery: Advances, Loading Strategies, Therapeutic Applications, and Clinical Challenges. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010045

Dieu LL, Kazsoki A, Zelkó R. Drug-Loaded Extracellular Vesicle-Based Drug Delivery: Advances, Loading Strategies, Therapeutic Applications, and Clinical Challenges. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleDieu, Linh Le, Adrienn Kazsoki, and Romána Zelkó. 2026. "Drug-Loaded Extracellular Vesicle-Based Drug Delivery: Advances, Loading Strategies, Therapeutic Applications, and Clinical Challenges" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010045

APA StyleDieu, L. L., Kazsoki, A., & Zelkó, R. (2026). Drug-Loaded Extracellular Vesicle-Based Drug Delivery: Advances, Loading Strategies, Therapeutic Applications, and Clinical Challenges. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010045