Development and Evaluation of Scaffolds Based on Perch Collagen–Hydroxyapatite for Advanced Synthetic Bone Substitutes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

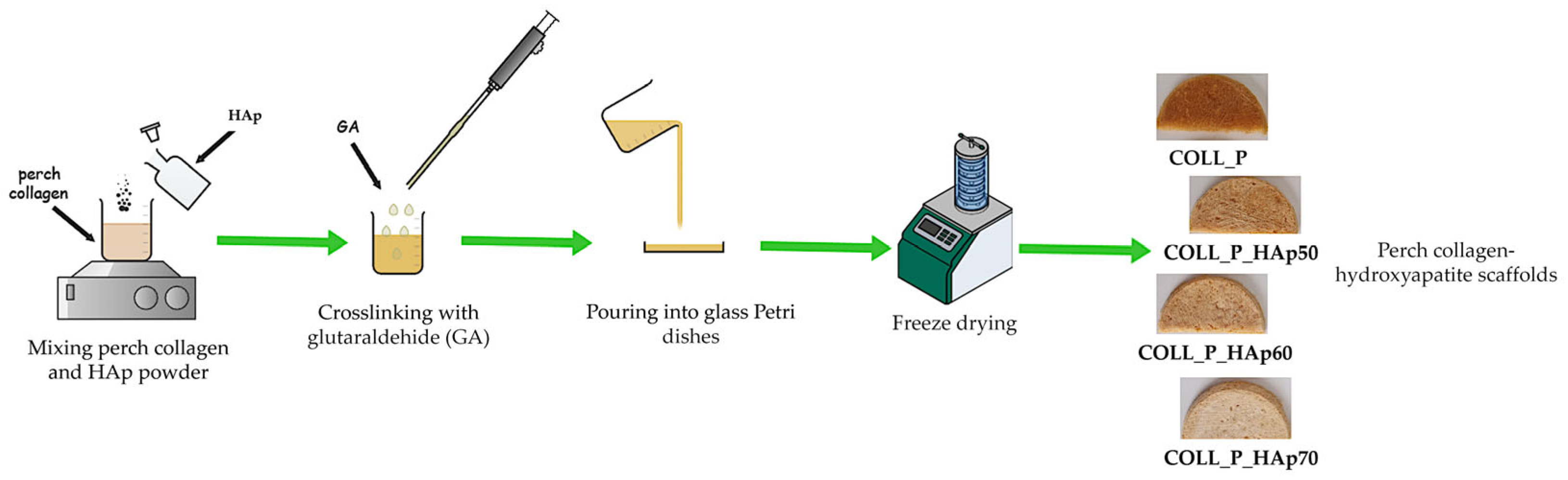

2.2.1. Preparation of Perch Collagen–HAp Scaffolds

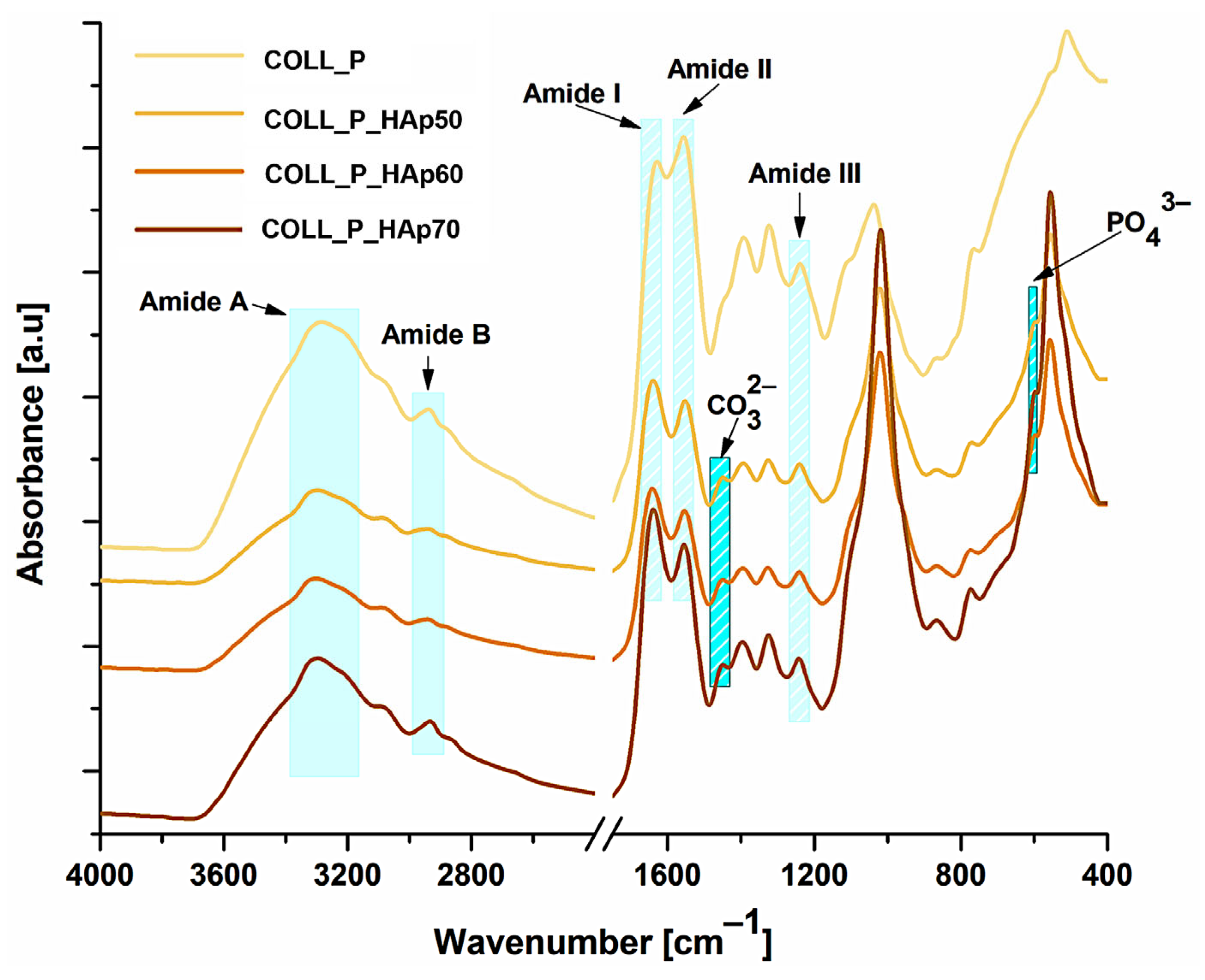

2.2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) of Collagen-HAp Scaffolds

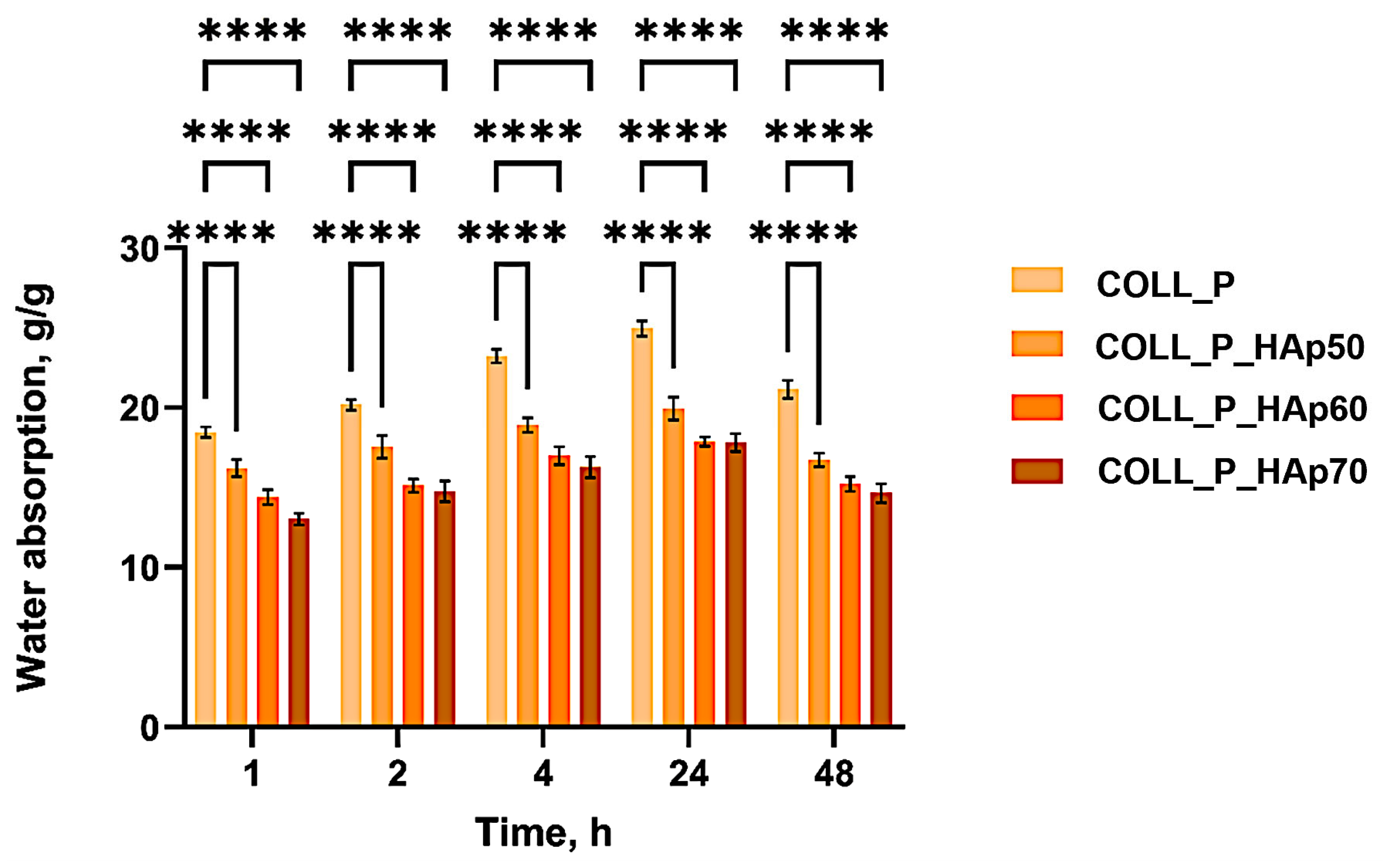

2.2.3. Water Absorption

2.2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Collagen-HAp Scaffolds and X-Ray Energy-Dispersive Spectrometry (X-EDS)

2.2.5. Mechanical Properties of Collagen-HAp Scaffolds

2.2.6. Enzymatic Degradation

2.2.7. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) of Collagen–HAp Scaffolds

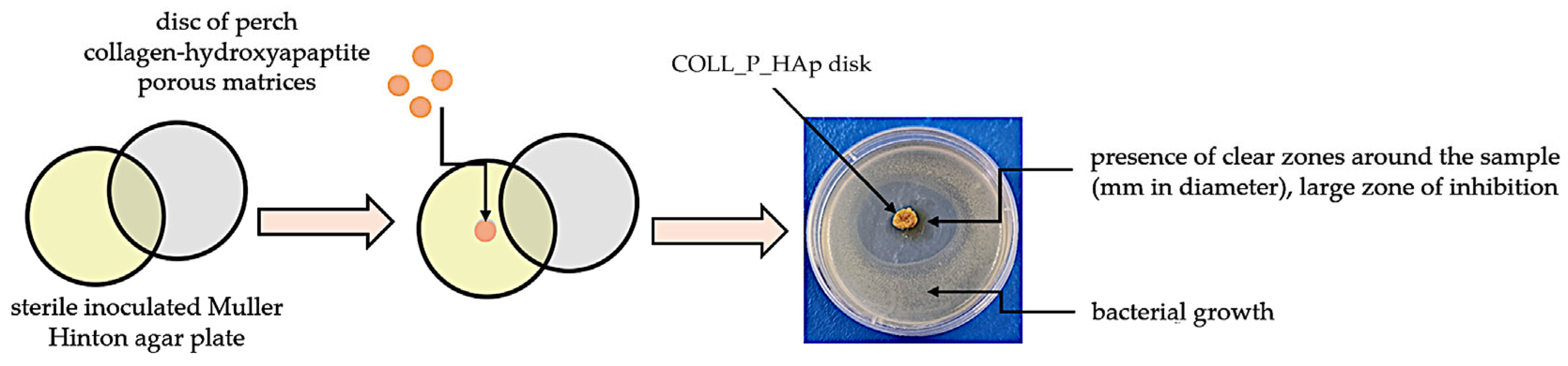

2.2.8. Antimicrobial Activity of Collagen–HAp Scaffolds

2.2.9. Statistical Analysis

2.2.10. Biocompatibility Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Analysis of Perch Collagen–HAp Scaffolds—FT-IR Spectra

3.2. Water Absorption of Perch Collagen–HAp Scaffolds

3.3. Morphological Analysis of Perch Collagen–HAp Scaffolds

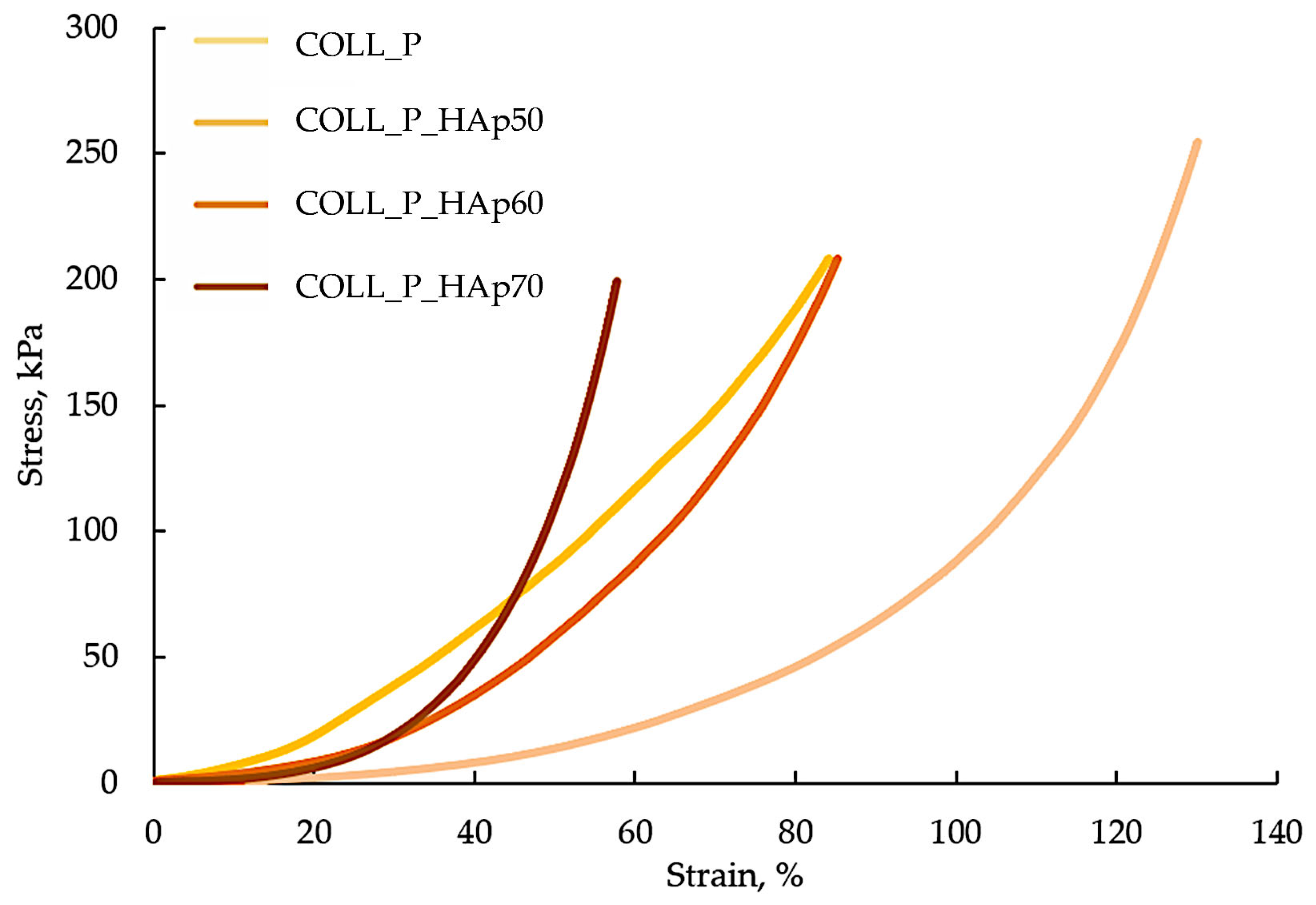

3.4. Compressive Properties of Collagen–HAp Scaffolds

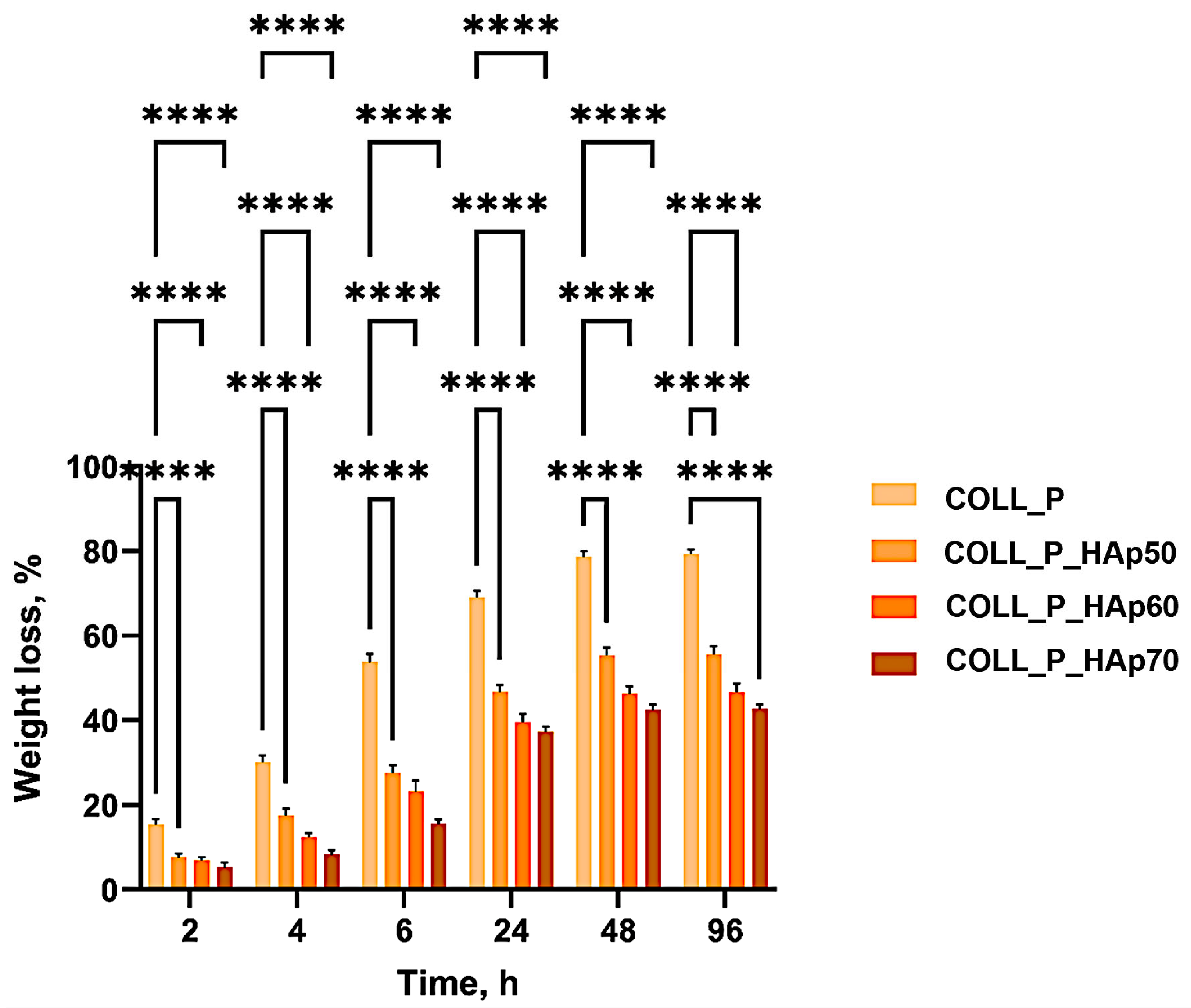

3.5. Enzymatic Degradation of Perch Collagen–HAp Scaffolds

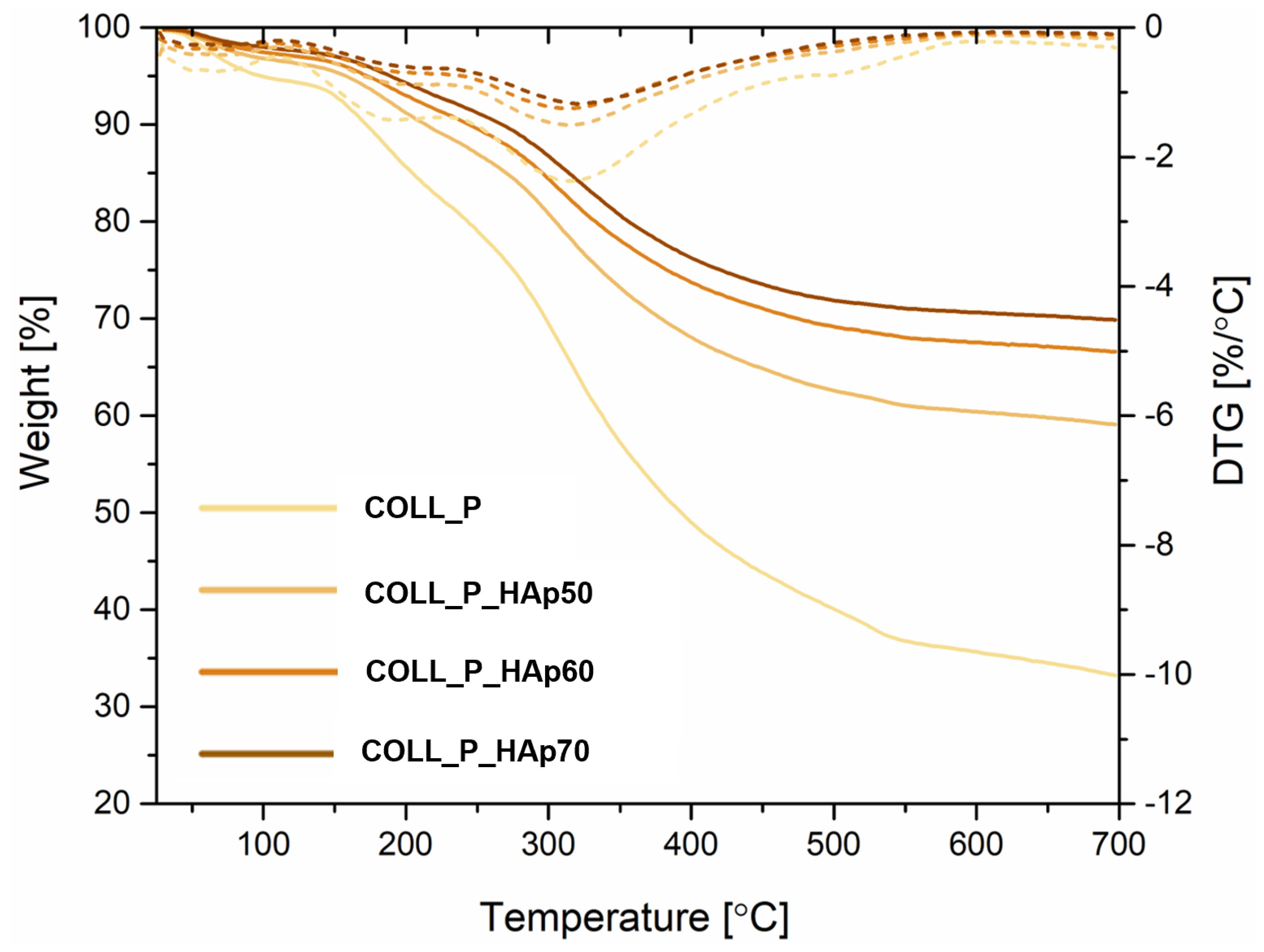

3.6. Perch Collagen–HAp Scaffolds Thermal Analysis

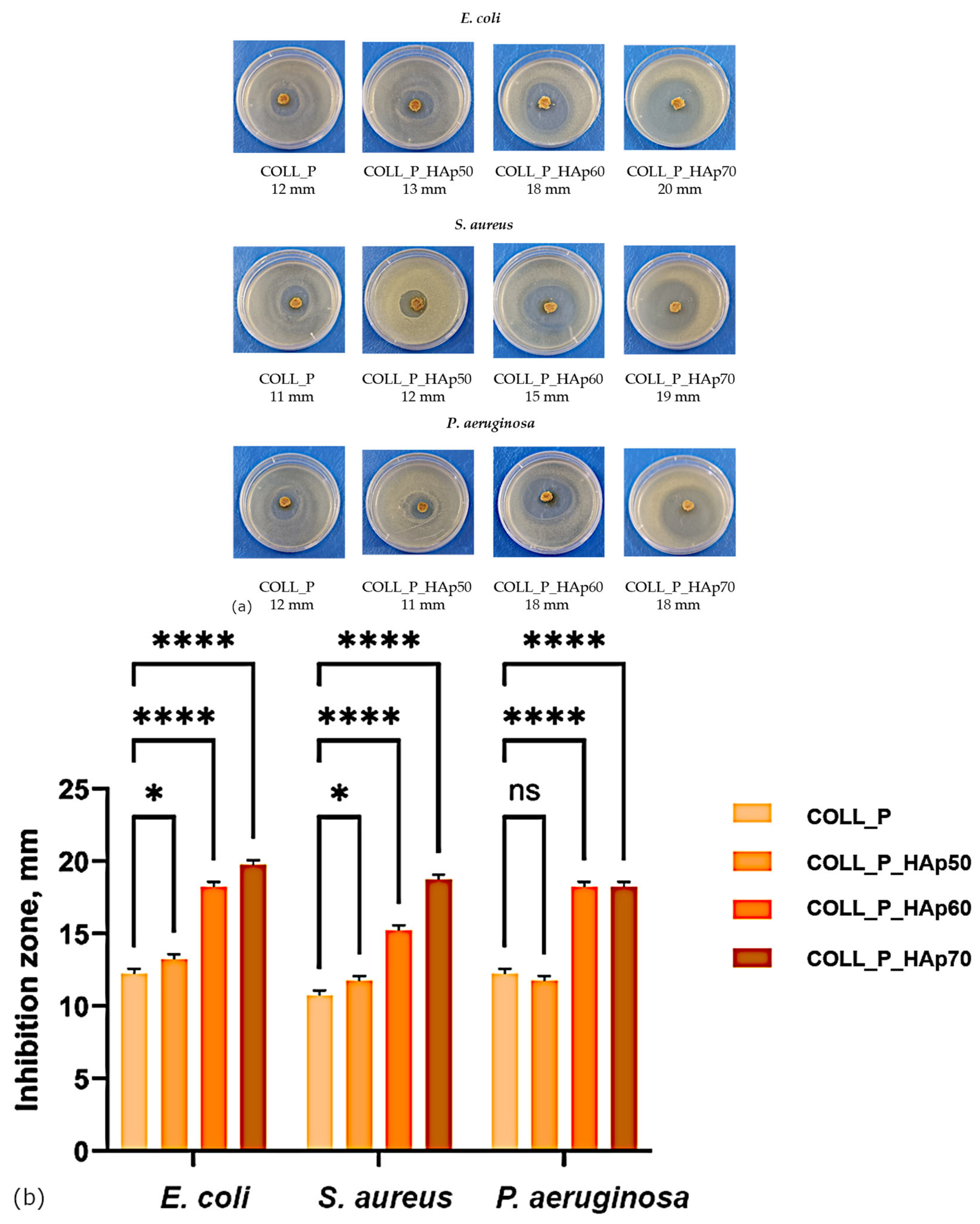

3.7. Collagen Porous Matrices Microbiological Analysis

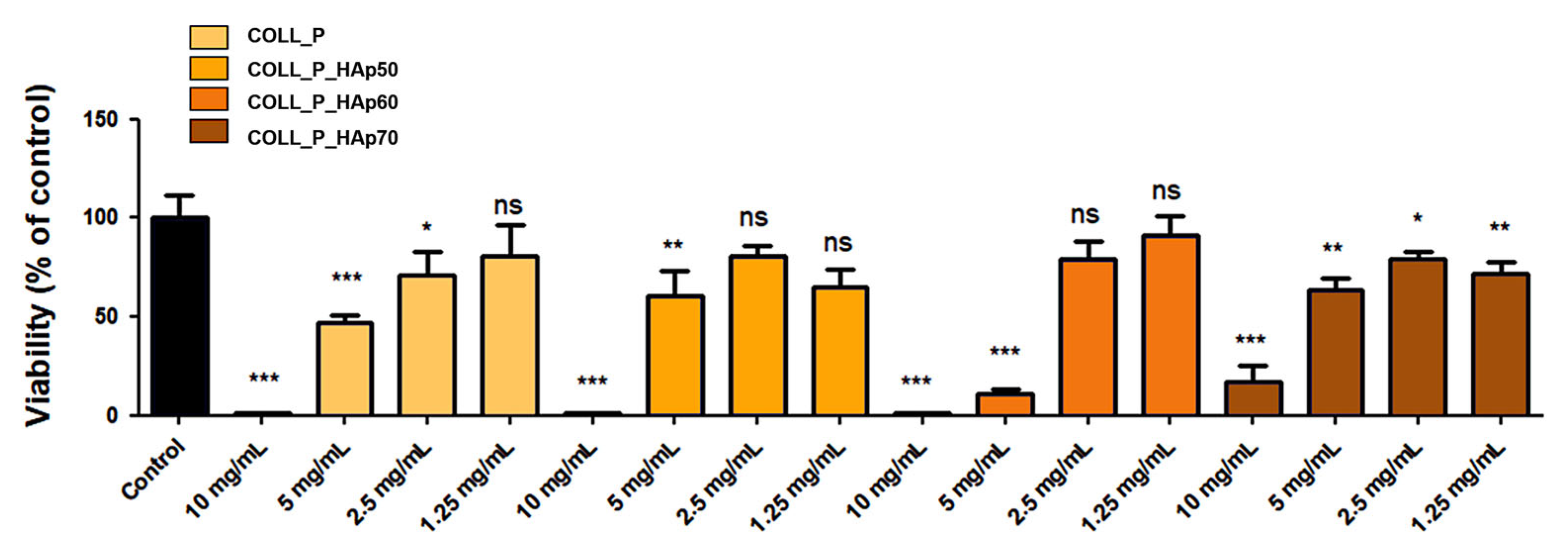

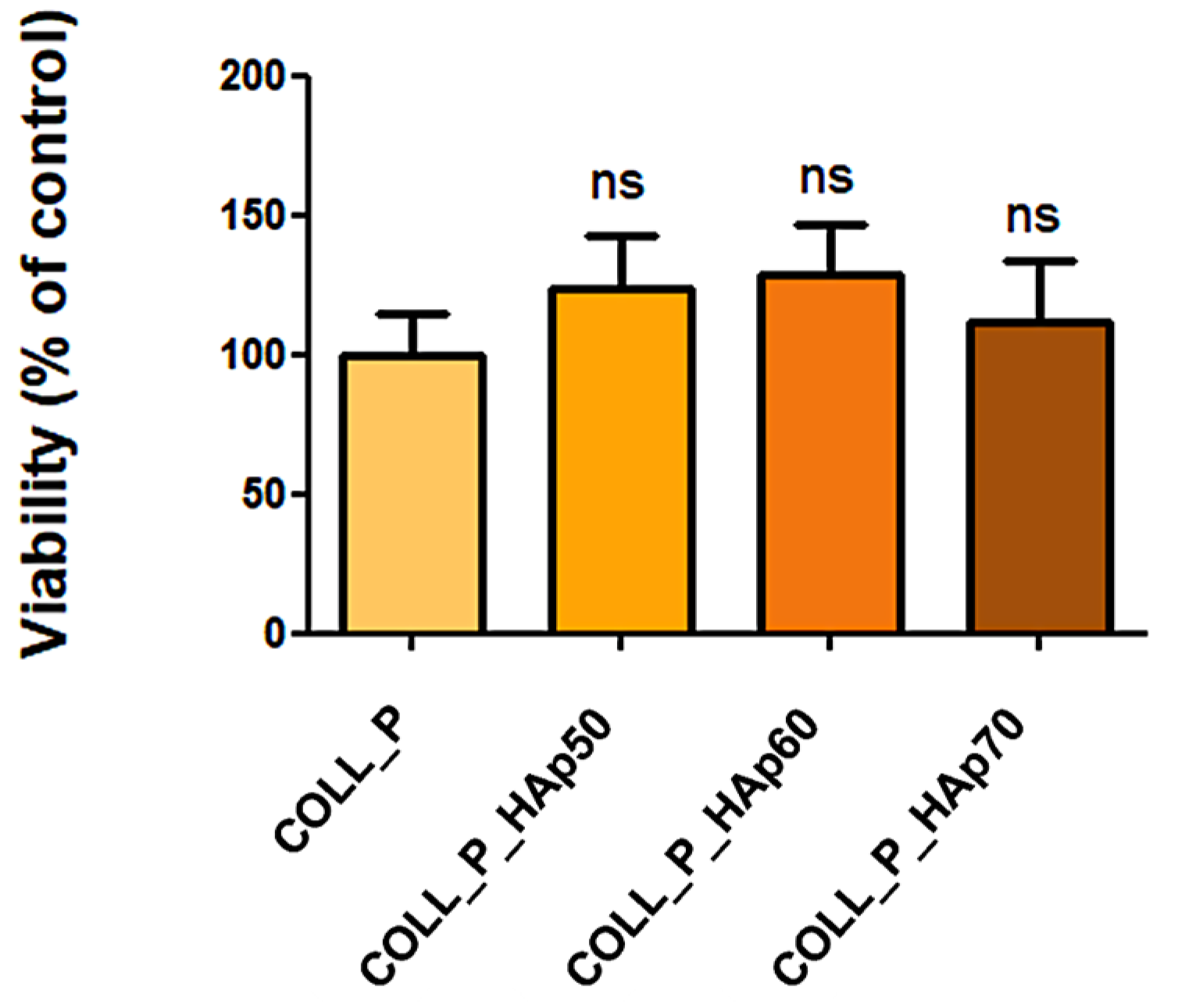

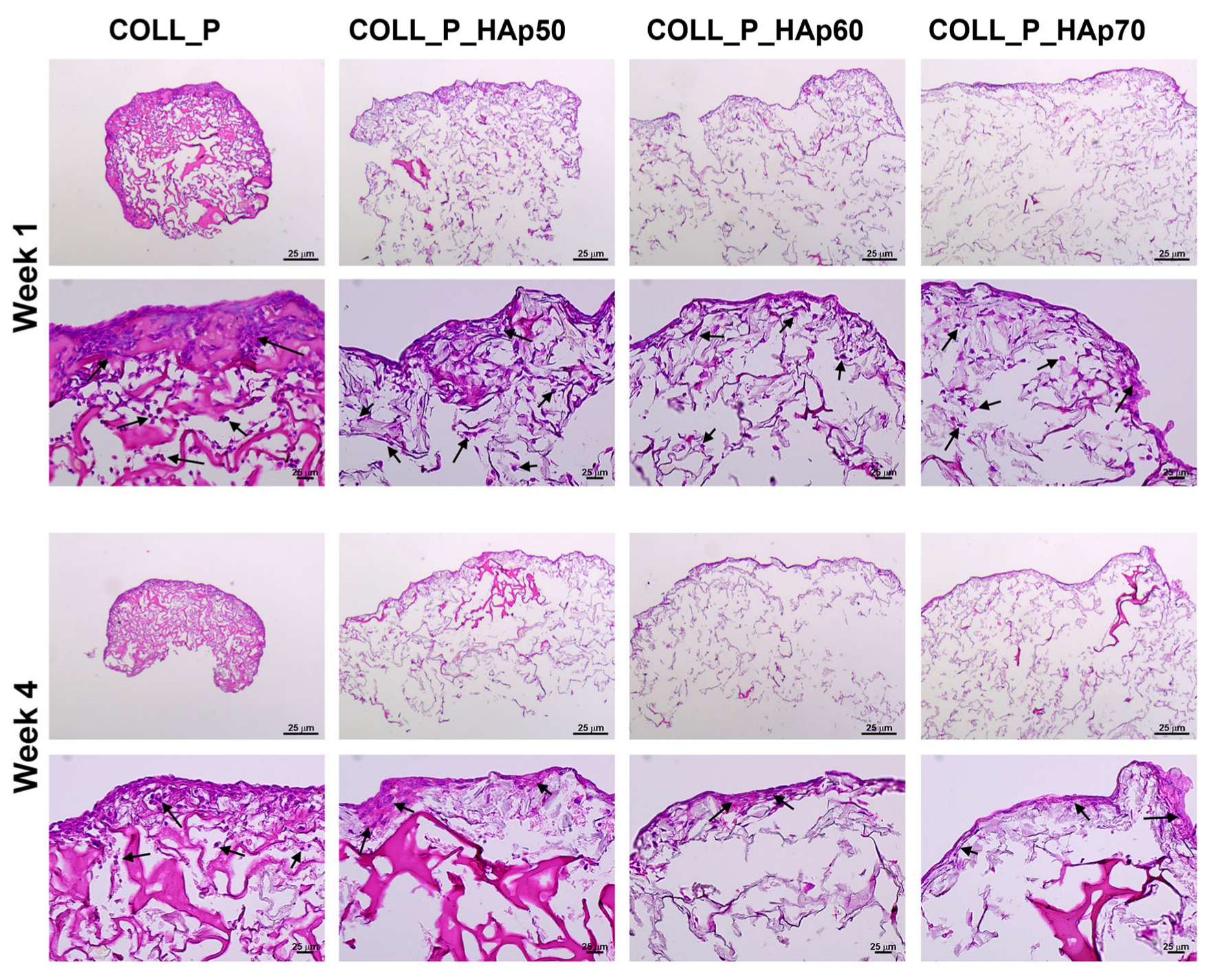

3.8. Biocompatibility Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Popescu, F.; Titorencu, I.; Albu Kaya, M.; Miculescu, F.; Tutuianu, R.; Coman, A.E.; Danila, E.; Marin, M.M.; Ancuta, D.-L.; Coman, C.; et al. Development of Innovative Biocomposites with Collagen, Keratin and Hydroxyapatite for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmen, S.; Kurt, S.; Timur, H.T.; Yavuz, O.; Kula, H.; Demir, A.Y.; Balcı, A. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Osteoporosis: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Tertiary Center. Medicina 2024, 60, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, J.A. Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-03928-966-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.-Y.; Bi, Q.; Zhao, C.; Chen, J.-Y.; Cai, M.-H.; Chen, X.-Y. Recent Advances in Biomaterials for the Treatment of Bone Defects. Organogenesis 2020, 16, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singaram, S.; Naidoo, M. The Physical, Psychological and Social Impact of Long Bone Fractures on Adults: A Review. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Bai, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, C.; Che, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Mater. Des. 2021, 210, 110049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Ren, Y.; Emmert, S.; Vučković, I.; Stojanovic, S.; Najman, S.; Schnettler, R.; Barbeck, M.; Schenke-Layland, K.; Xiong, X. The Use of Collagen-Based Materials in Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liang, Z.; Yang, L.; Du, W.; Yu, T.; Tang, H.; Li, C.; Qiu, H. The Role of Natural Polymers in Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Control. Release 2021, 338, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, N.; Ding, X.; Huang, R.; Jiang, R.; Huang, H.; Pan, X.; Min, W.; Chen, J.; Duan, J.-A.; Liu, P.; et al. Bone Tissue Engineering in the Treatment of Bone Defects. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xiao, J.; Yang, Q.; Lu, X.; Huang, Q.; Ai, X.; Li, B.; Sun, L.; Chen, L. Biomaterials for Surgical Repair of Osteoporotic Bone Defects. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 109684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinova, M.; Raykovska, M.; Simeonov, R.; Lolov, S.; Mourdjeva, M. Recent Advances in Bone Tissue Engineering: Enhancing the Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Regenerative Therapies. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V.P.; Oliveira, J.M.; Reis, R.L. Special Issue: Tissue Engineered Biomaterials and Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsi, S.; Singh, J.; Sehgal, S.S.; Sharma, N.K. Biomaterials for Tissue Engineered Bone Scaffolds: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, M.P. An Overview on the Big Players in Bone Tissue Engineering: Biomaterials, Scaffolds and Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liang, B.; Jiang, H.; Deng, Z.; Yu, K. Magnesium-Based Biomaterials as Emerging Agents for Bone Repair and Regeneration: From Mechanism to Application. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulina, N.V.; Khvostov, M.V.; Borodulina, I.A.; Makarova, S.V.; Zhukova, N.A.; Tolstikova, T.G. Substituted Hydroxyapatite and β-Tricalcium Phosphate as Osteogenesis Enhancers. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 33258–33269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senra, M.R.; Marques, M.D.F.V. Synthetic Polymeric Materials for Bone Replacement. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, M.; Are, R.P.; Babu, A.R. Nanocomposites for Bone Tissue Engineering Application. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, C.; Bai, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, H. Functionalization of Biomimetic Mineralized Collagen for Bone Tissue Engineering. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 20, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, K.H.; Seo, J.-H.; Pack, S.P. Biomimetic Scaffolds of Calcium-Based Materials for Bone Regeneration. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallick, M.; Are, R.P.; Babu, A.R. An Overview of Collagen/Bioceramic and Synthetic Collagen for Bone Tissue Engineering. Materialia 2022, 22, 101391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Wang, W.; Gong, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y. Collagen-Hydroxyapatite Based Scaffolds for Bone Trauma and Regeneration: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 1689–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.; Diogo, G.; Pires, R.; Reis, R.; Silva, T. 3D Biocomposites Comprising Marine Collagen and Silica-Based Materials Inspired on the Composition of Marine Sponge Skeletons Envisaging Bone Tissue Regeneration. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Wang, T.; He, L.; Liang, H.; Sun, J.; Huang, X.; Xie, W.; Niu, Y. Biological and Structural Properties of Curcumin-Loaded Graphene Oxide Incorporated Collagen as Composite Scaffold for Bone Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1505102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.-N.; Salamanca, E.; Chang, K.-C.; Shih, T.-C.; Chang, Y.-C.; Huang, H.-M.; Teng, N.-C.; Lin, C.-T.; Feng, S.-W.; Chang, W.-J. A Novel HA/β-TCP-Collagen Composite Enhanced New Bone Formation for Dental Extraction Socket Preservation in Beagle Dogs. Materials 2016, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.V.M.; Serricella, P.; Linhares, A.B.R.; Guerdes, R.M.; Borojevic, R.; Rossi, M.A.; Duarte, M.E.L.; Farina, M. Characterization of a Bovine Collagen–Hydroxyapatite Composite Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4987–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Cao, C.-B.; Guan, G.-Q. A Novel Porcine Acellular Dermal Matrix Scaffold Used in Periodontal Regeneration. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2013, 5, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lau, C.-S.; Liang, K.; Wen, F.; Teoh, S.H. Marine Collagen Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 74, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, T.; Tao, M.; Wang, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhu, C.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. Development of Recombinant Human Collagen-Based Porous Scaffolds for Skin Tissue Engineering: Enhanced Mechanical Strength and Biocompatibility. Polymers 2025, 17, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.; Mis Solval, K.E. Recent Advancements in Marine Collagen: Exploring New Sources, Processing Approaches, and Nutritional Applications. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Geng, X.; Li, W.; Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Qin, S. Comprehensive Review on Application Progress of Marine Collagen Cross-Linking Modification in Bone Repairs. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Knight, V.F.; Ahmad Farid, M.A.; Andou, Y.; Jenol, M.A.; Naveen, J.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Rani, M.S.A. Marine-Derived Collagen Composites for Bone Regeneration: Extraction and Performance Evaluation. In Polymer Composites Derived from Animal Sources; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 259–275. ISBN 978-0-443-22414-0. [Google Scholar]

- Coman, A.E.; Marin, M.M.; Roșca, A.M.; Albu Kaya, M.G.; Constantinescu, R.R.; Titorencu, I. Marine Resources Gels as Main Ingredient for Wound Healing Biomaterials: Obtaining and Characterization. Gels 2024, 10, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hue, C.T.; Hang, N.T.M.; Razumovskaya, R.G. Physicochemical Characterization of Gelatin Extracted from European Perch (Perca fluviatilis) and Volga Pikeperch (Sander volgensis) Skins. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2017, 17, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaas, N.; Hammami, R.; Gomaa, A.; Bédard, F.; Biron, É.; Subirade, M.; Beaulieu, L.; Fliss, I. Collagencin, an Antibacterial Peptide from Fish Collagen: Activity, Structure and Interaction Dynamics with Membrane. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 473, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, L.F.B.; Eufrásio Cruz, M.A.; Aguilar, G.J.; Tapia-Blácido, D.R.; Da Silva Ferreira, M.E.; Maniglia, B.C.; Bottini, M.; Ciancaglini, P.; Ramos, A.P. Synthesis of Antibacterial Hybrid Hydroxyapatite/Collagen/Polysaccharide Bioactive Membranes and Their Effect on Osteoblast Culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalaivasan, N. Collagen-Composite Scaffolds for Alveolar Bone and Dental Tissue Regeneration: Advances in Material Development and Clinical Applications—A Narrative Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albu, M.G.; Ferdes, M.; Kaya, D.A.; Ghica, M.V.; Titorencu, I.; Popa, L.; Albu, L. Collagen Wound Dressings with Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2012, 555, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S. (Ed.) Biomedical and Pharmacological Applications of Marine Collagen; MDPI—Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-3-0365-6352-7. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.C.; Barros, A.A.; Aroso, I.M.; Fassini, D.; Silva, T.H.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Extraction of Collagen/Gelatin from the Marine Demosponge Chondrosia reniformis (Nardo, 1847) Using Water Acidified with Carbon Dioxide—Process Optimization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 6922–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.-C.; Chiu, C.-S.; Chan, Y.-J.; Mulio, A.T.; Li, P.-H. Characterization and Biological Properties of Marine By-Product Collagen through Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 29, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Y.; Wan, P.; Huang, Z.; Ma, F.; Li, J. Discovering Novel Type I Collagen Fragments from Cyprinus Carpio Supporting Bone Regeneration. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2025, 25, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalekha, A.; Sridhar, H.; Srinivasan, S.; Anumaiya, V.; Anandasadagopan, S.K.; Pandurangan, A.K. Integrative Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation of Rutin-Infused Collagen–Hydroxyapatite Scaffold for Promoting Osteochondral Regeneration. 3 Biotech 2025, 15, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenov, M.; Creager, E.; Ben-Porat, O.; Swersky, K.; Zemel, R.; Boutilier, C. Optimizing Long-Term Social Welfare in Recommender Systems: A Constrained Matching Approach 2020. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 12–18 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Demeter, M.; Călina, I.; Scărișoreanu, A.; Micutz, M.; Kaya, M.A. Correlations on the Structure and Properties of Collagen Hydrogels Produced by E-Beam Crosslinking. Materials 2022, 15, 7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Azaïs, T.; Robin, M.; Vallée, A.; Catania, C.; Legriel, P.; Pehau-Arnaudet, G.; Babonneau, F.; Giraud-Guille, M.-M.; Nassif, N. The Predominant Role of Collagen in the Nucleation, Growth, Structure and Orientation of Bone Apatite. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, A.; Kubo, T.; Doi, K.; Hayashi, K.; Morita, K.; Yokota, R.; Hayashi, H.; Hirata, I.; Okazaki, M.; Akagawa, Y. Bone Formation Ability of Carbonate Apatite-Collagen Scaffolds with Different Carbonate Contents. Dent. Mater. J. 2009, 28, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Euw, S.; Wang, Y.; Laurent, G.; Drouet, C.; Babonneau, F.; Nassif, N.; Azaïs, T. Bone Mineral: New Insights into Its Chemical Composition. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.C.; Ribeiro, G.L.; Marques, R.C. In Situ Hydroxyapatite Synthesis: Influence of Collagen on Its Structural and Morphological Characteristic. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2012, 3, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, R.G.; Montanheiro, T.L.A.; Montagna, L.S.; Prado, R.F.D.; Lemes, A.P.; Bastos Campos, T.M.; Thim, G.P. Water Uptake in PHBV/Wollastonite Scaffolds: A Kinetics Study. J. Compos. Sci. 2019, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirtaghavi, A.; Baldwin, A.; Tanideh, N.; Zarei, M.; Muthuraj, R.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, G.; Geng, J.; Jin, H.; Luo, J. Crosslinked Porous Three-Dimensional Cellulose Nanofibers-Gelatine Biocomposite Scaffolds for Tissue Regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1949–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska-Sionkowska, M.; Warżyńska, O.; Kaczmarek-Szczepańska, B.; Łukowicz, K.; Osyczka, A.M.; Walczak, M. Preparation and Characterization of Fish Skin Collagen Material Modified with β-Glucan as Potential Wound Dressing. Materials 2021, 14, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzbicka, A.; Bartniak, M.; Waśko, J.; Kolesińska, B.; Grabarczyk, J.; Bociaga, D. The Impact of Gelatin and Fish Collagen on Alginate Hydrogel Properties: A Comparative Study. Gels 2024, 10, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshidfar, N.; Tanideh, N.; Emami, Z.; Aslani, F.S.; Sarafraz, N.; Khodabandeh, Z.; Zare, S.; Farshidfar, G.; Nikoofal-Sahlabadi, S.; Tayebi, L.; et al. Incorporation of Curcumin into Collagen-Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Nanocomposite Scaffold: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 4558–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabandeh, Z.; Tanideh, N.; Aslani, F.S.; Jamhiri, I.; Zare, S.; Alizadeh, N.; Safari, A.; Farshidfar, N.; Dara, M.; Zarei, M. A Comparative in Vitro and in Vivo Study on Bone Tissue Engineering Potential of the Collagen/Nano-Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds Loaded with Ginger Extract and Curcumin. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Q.L.; Choong, C. Three-Dimensional Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: Role of Porosity and Pore Size. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2013, 19, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukasheva, F.; Adilova, L.; Dyussenbinov, A.; Yernaimanova, B.; Abilev, M.; Akilbekova, D. Optimizing Scaffold Pore Size for Tissue Engineering: Insights across Various Tissue Types. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1444986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Mancilla, B.H.; Araiza-Téllez, M.A.; Flores-Flores, J.O.; Piña-Barba, M.C. Physico-Chemical Characterization of Collagen Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2016, 14, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayon, I.; Szarlej, P.; Łapiński, M.; Kucińska-Lipka, J. Polyurethane Composite Scaffolds Modified with the Mixture of Gelatin and Hydroxyapatite Characterized by Improved Calcium Deposition. Polymers 2020, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, R.-L.; Sun, R.-X.; Li, Q.; Fu, C.; Chen, K.-Z. Synthesis of Ultralong Hydroxyapatite Micro/Nanoribbons and Their Application as Reinforcement in Collagen Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 5914–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajeri, S.; Hosseinkhani, H.; Golshan Ebrahimi, N.; Nikfarjam, L.; Soleimani, M.; Kajbafzadeh, A.-M. Proliferation and Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cell on Collagen Sponge Reinforced with Polypropylene/Polyethylene Terephthalate Blend Fibers. Tissue Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 3821–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, T.; Xu, R.; Ma, P.; Zhao, J.; Mi, Y. Biodegradable and Mechanically Resilient Recombinant Collagen/PEG/Catechol Cryogel Hemostat for Deep Non-Compressible Hemorrhage and Wound Healing. Gels 2025, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antebi, B.; Cheng, X.; Harris, J.N.; Gower, L.B.; Chen, X.-D.; Ling, J. Biomimetic Collagen–Hydroxyapatite Composite Fabricated via a Novel Perfusion-Flow Mineralization Technique. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2013, 19, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, D.; Lin, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X. Cellulose Nanocrystal Reinforced Collagen-Based Nanocomposite Hydrogel with Self-Healing and Stress-Relaxation Properties for Cell Delivery. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 2400–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Eschweiler, J.; Maffulli, N.; Hildebrand, F.; Schenker, H. Functionalised High-Performance Oxide Ceramics with Bone Morphogenic Protein 2 (BMP-2) Induced Ossification: An In Vivo Study. Life 2022, 12, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ma, J.-X.; Xu, L.; Gu, X.-S.; Ma, X.-L. Biodegradable Materials for Bone Defect Repair. Mil. Med. Res 2020, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, H.; Raz, A.; Zakeri, S.; Dinparast Djadid, N. Therapeutic Applications of Collagenase (Metalloproteases): A Review. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2016, 6, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Z.; Wang, K.; Xu, L.-F.; Su, C.; Gong, J.-S.; Shi, J.-S.; Ma, X.-D.; Xie, N.; Qian, J.-Y. Unlocking the Potential of Collagenases: Structures, Functions, and Emerging Therapeutic Horizons. BioDesign Res. 2024, 6, 0050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, H.W.; Zhang, Y.; Naffa, R.; Prabakar, S. Monitoring the Degradation of Collagen Hydrogels by Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum. Gels 2020, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prelipcean, A.-M.; Iosageanu, A.; Gaspar-Pintiliescu, A.; Moldovan, L.; Craciunescu, O.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Negreanu-Pirjol, B.; Mitran, R.-A.; Marin, M.; D’Amora, U. Marine and Agro-Industrial By-Products Valorization Intended for Topical Formulations in Wound Healing Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozec, L.; Odlyha, M. Thermal Denaturation Studies of Collagen by Microthermal Analysis and Atomic Force Microscopy. Biophys. J. 2011, 101, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yu, Z.; Wang, B.; Chiou, B.-S. Changes in Structures and Properties of Collagen Fibers during Collagen Casing Film Manufacturing. Foods 2023, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallela, R.; Venkatesan, J.; Janapala, V.R.; Kim, S. Biophysicochemical Evaluation of Chitosan-hydroxyapatite-marine Sponge Collagen Composite for Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2012, 100, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, E.P.; Rodrigues, M.Á.V.; Martins, V.C.A.; Plepis, A.M.G.; Fuhrmann-Lieker, T.; Horn, M.M. Mineralization of Phosphorylated Fish Skin Collagen/Mangosteen Scaffolds as Potential Materials for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Molecules 2021, 26, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, H.; Jin, S.; Yan, F.; Qu, X.; Chen, X.; Peng, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Biomaterials for Bone Infections: Antibacterial Mechanisms and Immunomodulatory Effects. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1589653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Aroca, Á.; Cano-Vicent, A.; Sabater, I.; Serra, R.; El-Tanani, M.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Mishra, Y.K. Scaffolds in the Microbial Resistant Era: Fabrication, Materials, Properties and Tissue Engineering Applications. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 16, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municoy, S.; Antezana, P.E.; Bellino, M.G.; Desimone, M.F. Development of 3D-Printed Collagen Scaffolds with In-Situ Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Antibiotics 2022, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanain, M.; Abdel-Ghafar, H.M.; Hamouda, H.I.; El-Hosiny, F.I.; Ewais, E.M.M. Enhanced Antimicrobial Efficacy of Hydroxyapatite-Based Composites for Healthcare Applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and HealthCare (EDQM) Council of Europe. Microbiological Quality of Non-Sterile Pharmaceutical Preparations and Substances for Pharmaceutical Use. In European Pharmacopoeia, 11th ed.; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and HealthCare (EDQM) Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2023; Chapter 5.1.4. [Google Scholar]

- Tyski, S.; Burza, M.; Laudy, A.E. Microbiological Contamination of Medicinal Products —Is It a Significant Problem? Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidswell, E.C.; Tirumalai, R.S.; Gross, D.D. Clarifications on the Intended Use of USP Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Microbial Enumeration Tests. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2024, 78, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorca, B.V.; Kaya, D.A.; Kaya, M.G.A.; Enachescu, M.; Ghetu, D.-M.; Enache, L.-B.; Boerasu, I.; Coman, A.E.; Rusu, L.C.; Constantinescu, R.; et al. Bone Fillers with Balance Between Biocompatibility and Antimicrobial Properties. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Name | COLL_P, % | Hap *, % | GA *, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| COLL_P | 100 | 0 | 0.5 |

| COLL_P_HAp50 | 50 | 50 | 0.5 |

| COLL_P_HAp60 | 40 | 60 | 0.5 |

| COLL_P_HAp70 | 30 | 70 | 0.5 |

| Sample | Mass Loss, % | Residual Mass, % | Tmax (DTG), °C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25–100, °C | 100–400, °C | 400–700, °C | |||

| COLL_P | 5 | 46 | 16 | 33 | 315 |

| COLL_P_HAp50 | 4 | 28 | 9 | 59 | 315 |

| COLL_P_HAp60 | 3 | 23 | 7 | 67 | 315 |

| COLL_P_HAp70 | 2 | 22 | 6 | 70 | 321 |

| Sample | TAMC * (CFU/g) | TYMC ** (CFU/g) | Detection of E. coli | Detection of S. aureus | Detection of P. aeruginosa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLL_P | 6.33 | <1 | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| COLL_P_HAp50 | 2.33 | <1 | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| COLL_P_HAp60 | 1.66 | <1 | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| COLL_P_HAp70 | 1.33 | <1 | Absent | Absent | Absent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Coman, A.E.; Rosca, A.M.; Marin, M.M.; Albu Kaya, M.G.; Gabor, R.; Usurelu, C.; Ghica, M.V.; Dinca, L.; Titorencu, I. Development and Evaluation of Scaffolds Based on Perch Collagen–Hydroxyapatite for Advanced Synthetic Bone Substitutes. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010033

Coman AE, Rosca AM, Marin MM, Albu Kaya MG, Gabor R, Usurelu C, Ghica MV, Dinca L, Titorencu I. Development and Evaluation of Scaffolds Based on Perch Collagen–Hydroxyapatite for Advanced Synthetic Bone Substitutes. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleComan, Alina Elena, Ana Maria Rosca, Maria Minodora Marin, Madalina Georgiana Albu Kaya, Raluca Gabor, Catalina Usurelu, Mihaela Violeta Ghica, Laurentiu Dinca, and Irina Titorencu. 2026. "Development and Evaluation of Scaffolds Based on Perch Collagen–Hydroxyapatite for Advanced Synthetic Bone Substitutes" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010033

APA StyleComan, A. E., Rosca, A. M., Marin, M. M., Albu Kaya, M. G., Gabor, R., Usurelu, C., Ghica, M. V., Dinca, L., & Titorencu, I. (2026). Development and Evaluation of Scaffolds Based on Perch Collagen–Hydroxyapatite for Advanced Synthetic Bone Substitutes. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010033