Evaluation of the Functional Suitability of Carboxylate Chlorin e6 Derivatives for Use in Radionuclide Diagnostics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Photosensitizers Preparation

2.2. Radiolabelling Optimization

2.2.1. Labelling Using Tin (II) Chloride as a Reducing Agent

2.2.2. Labelling Using Tricarbonyl Technetium-99m Precursor

2.3. In Vitro Characterization

2.4. In Vivo Characterization

3. Results

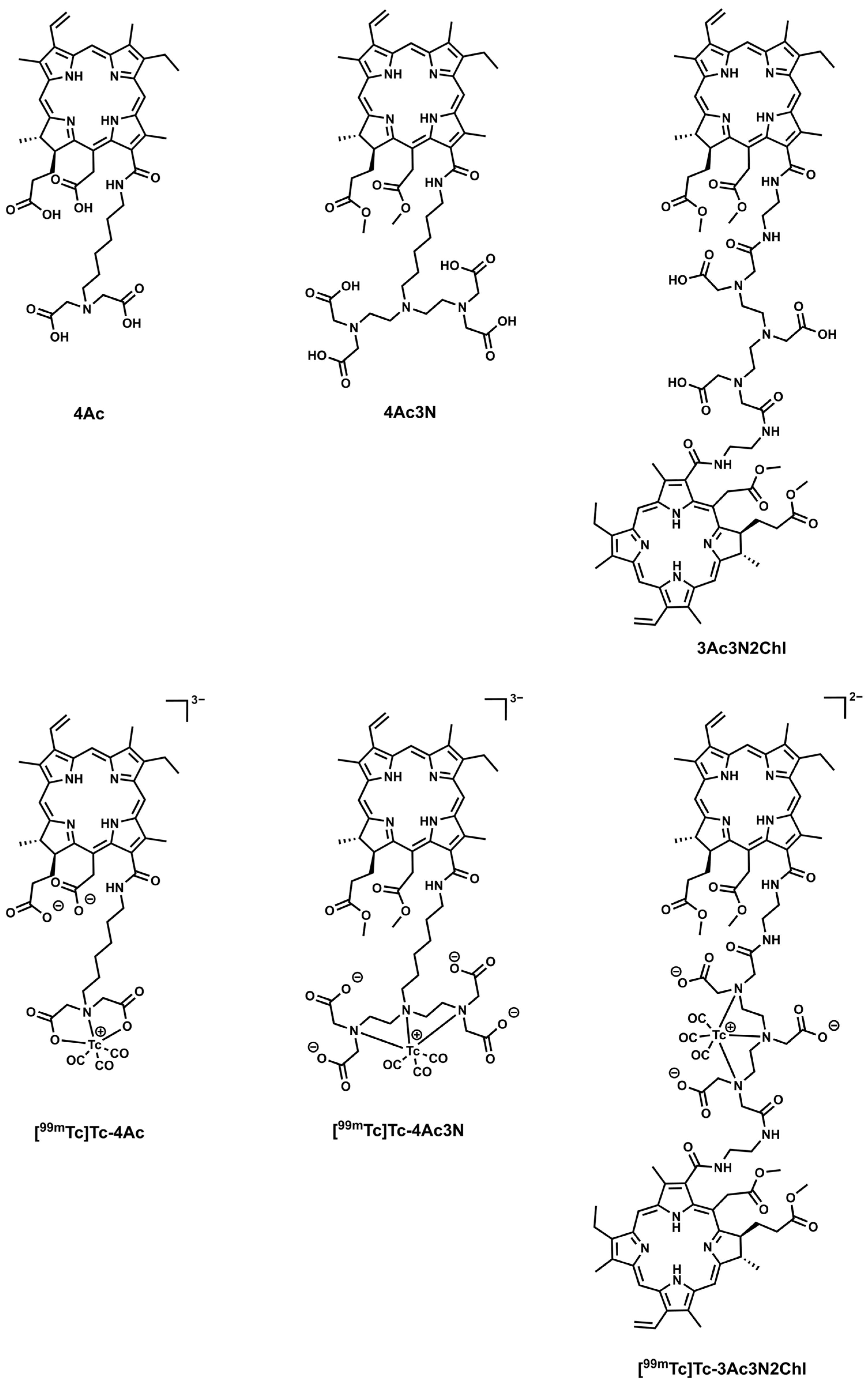

3.1. Synthesis and Radiolabelling of the Chlorins Complexes

3.1.1. Labelling Using Tin (II) Chloride as a Reducing Agent

3.1.2. Labelling Using Tricarbonyl Technetium-99m Precursor

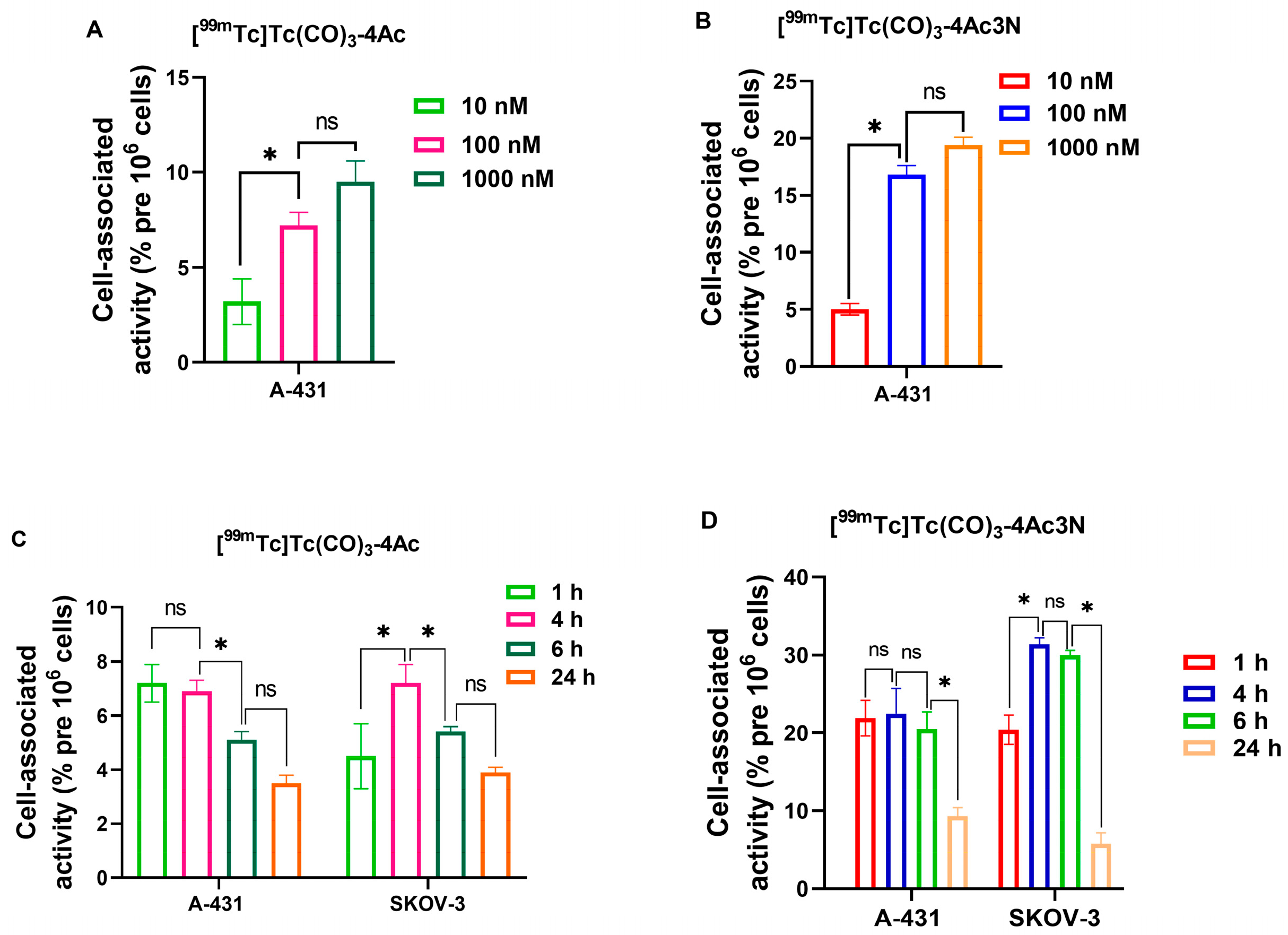

3.2. In Vitro Characterization

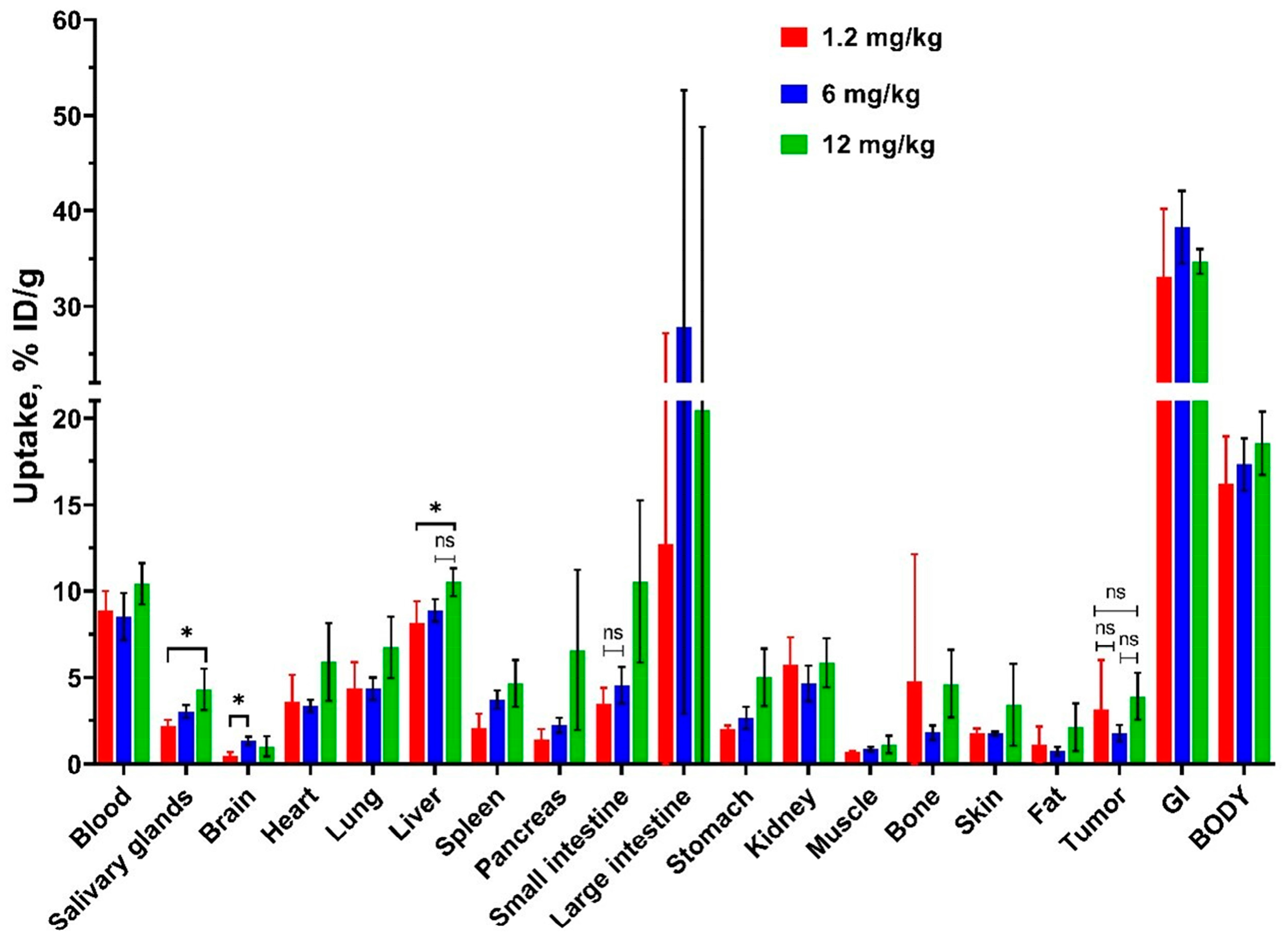

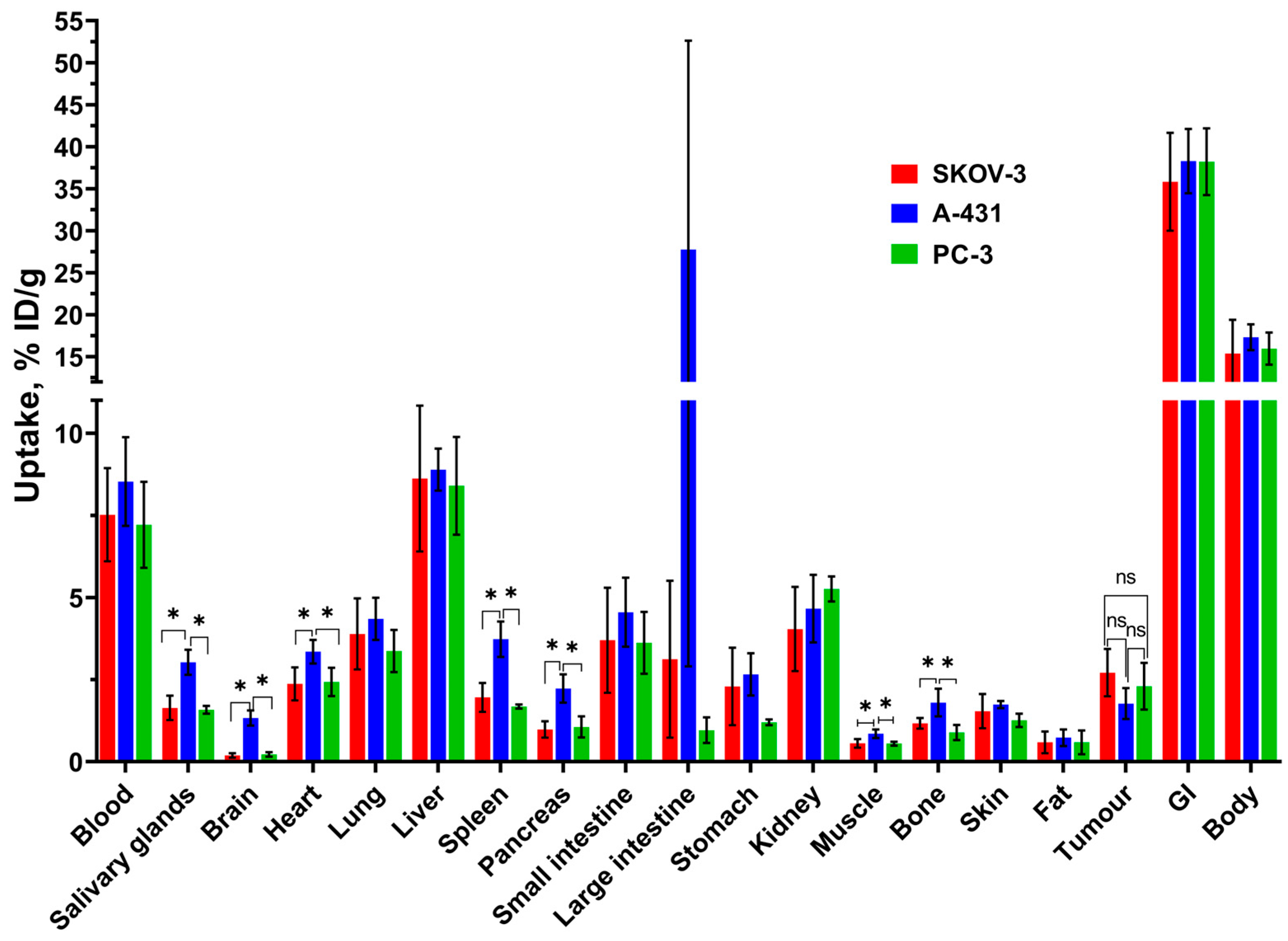

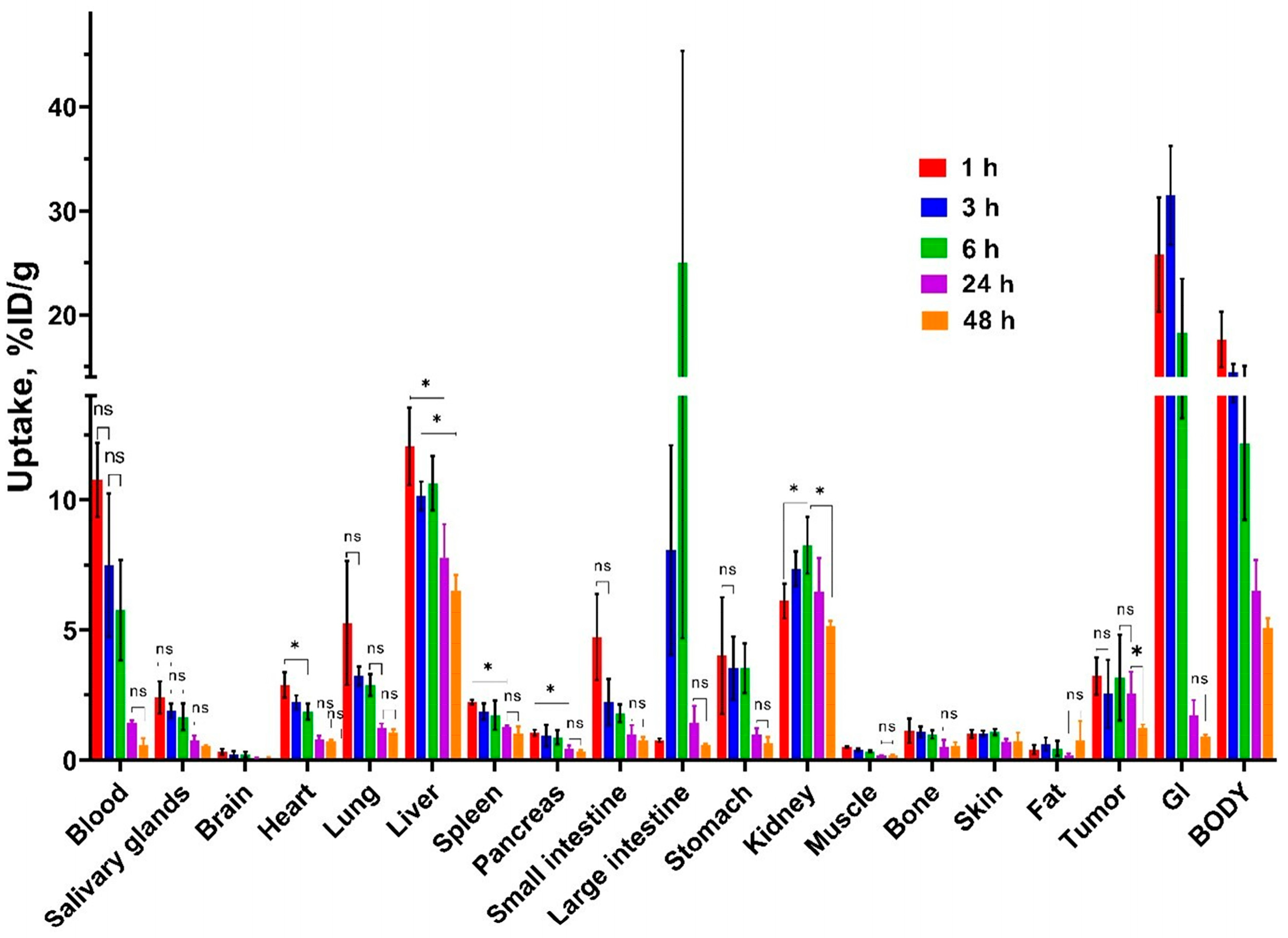

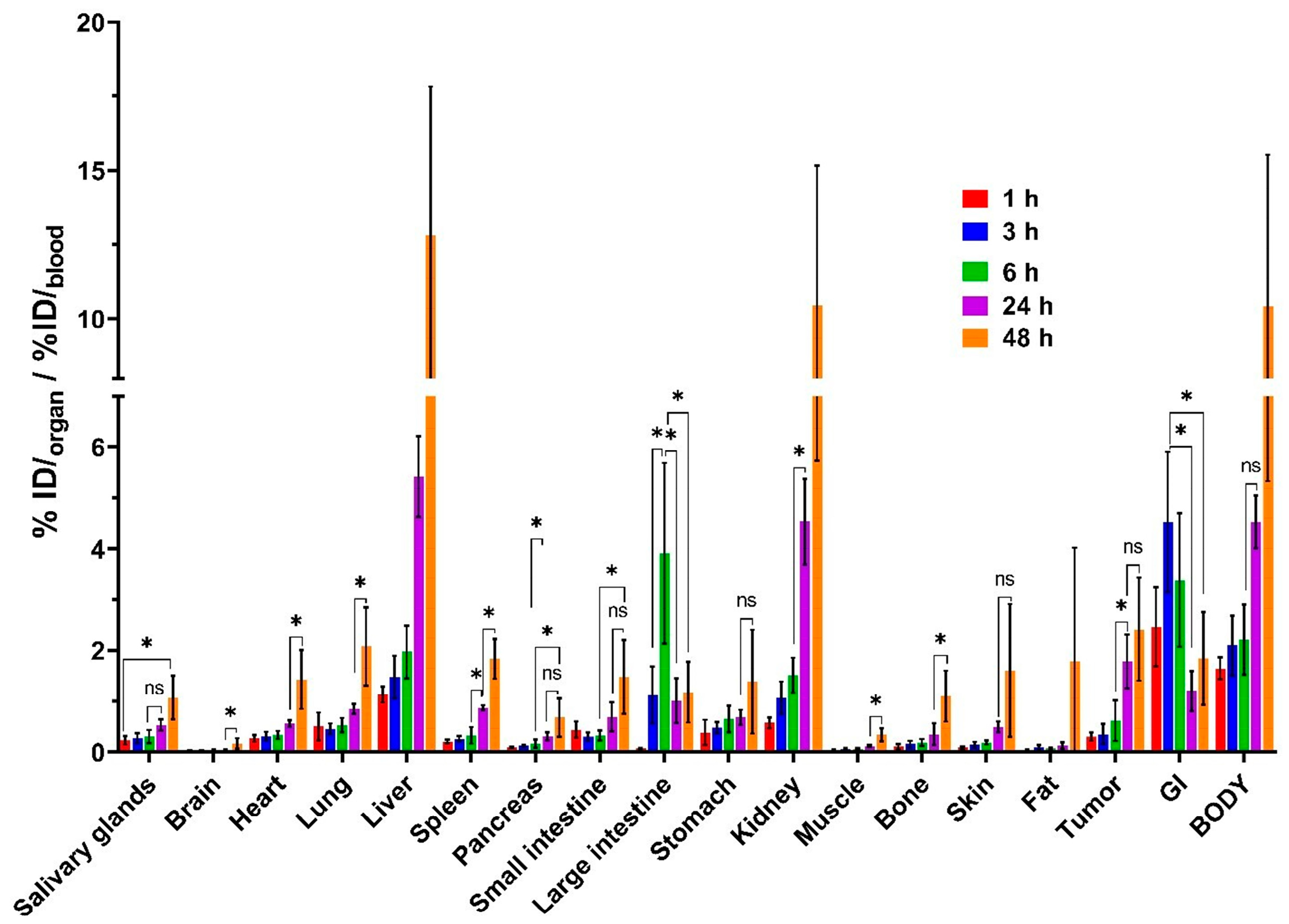

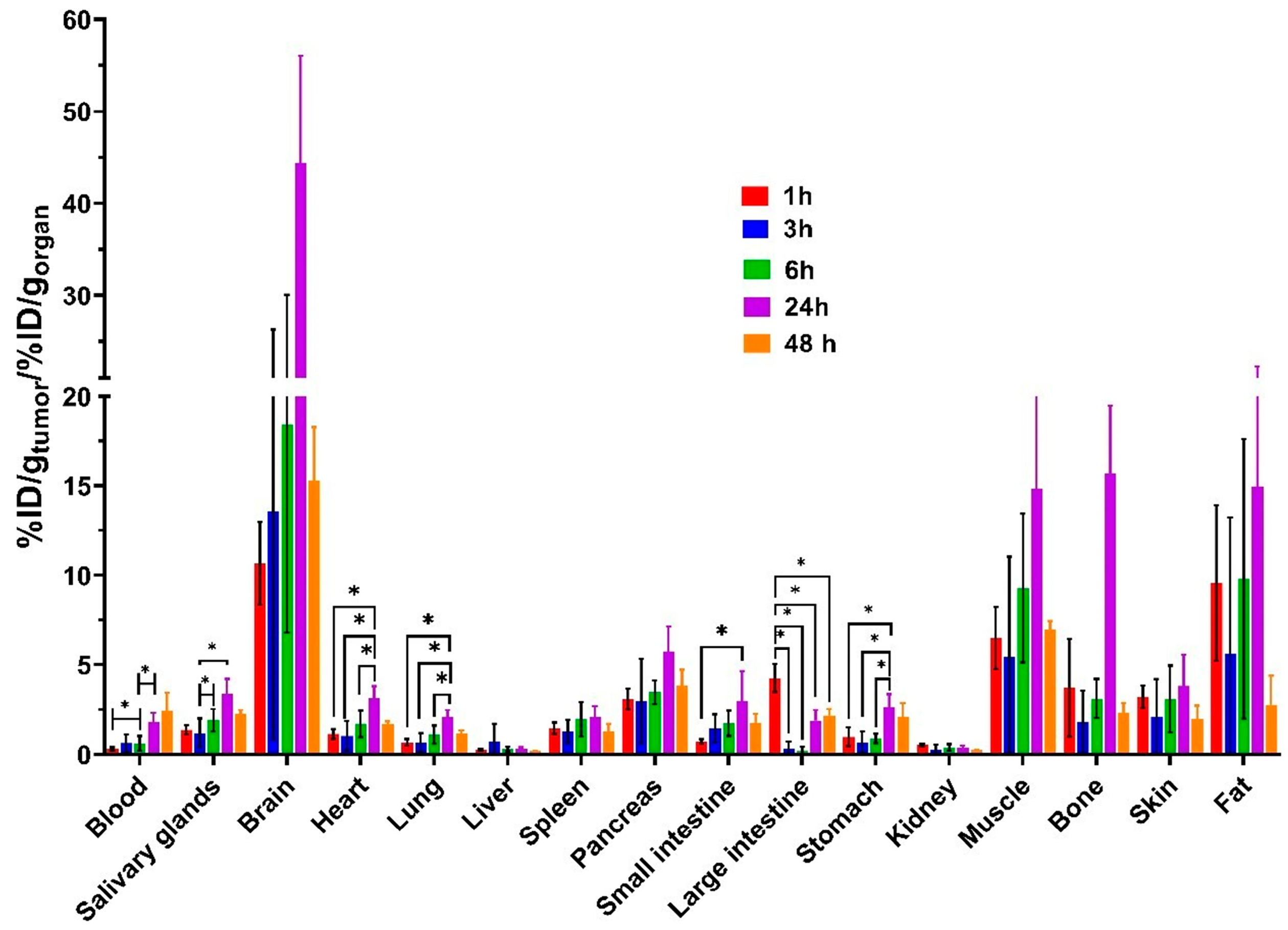

3.3. In Vivo Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kazuma, S.; Sultan, D.; Zhao, Y.; Detering, L.; You, M.; Luehmann, H.; Abdalla, D.; Liu, Y. Recent Advances of Radionuclide-Based Molecular Imaging of Atherosclerosis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 5267–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflot, V.R.; Gaivoronsky, A.V.; Lobanova, E.I. Synthesis of Thermosensitive Copolymers of N-Isopropylacrylamide with 2-Aminoethylmethacrylate Hydrochloride. Fine Chem. Technol. 2021, 16, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meulen, N.P.; Strobel, K.; Lima, T.V.M. New Radionuclides and Technological Advances in SPECT and PET Scanners. Cancers 2021, 13, 6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonti, R.; Conson, M.; Del Vecchio, S. PET/CT in Radiation Oncology. Semin. Oncol. 2019, 46, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.S.; Windhorst, A.D.; Zeglis, B.M. (Eds.) Radiopharmaceutical Chemistry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Edwards, D.S. Bifunctional Chelators for Therapeutic Lanthanide Radiopharmaceuticals. Bioconjug. Chem. 2001, 12, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannopoulou, D. Technetium-99m Radiochemistry for Pharmaceutical Applications. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2017, 60, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Liu, C.; Miao, Y.; Wang, R.; Hu, K. Radiopharmaceuticals and Their Applications in Medicine. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgouros, G.; Bodei, L.; McDevitt, M.R.; Nedrow, J.R. Radiopharmaceutical Therapy in Cancer: Clinical Advances and Challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, A.; Impens, N.R.E.N.; Gijs, M.; D’Huyvetter, M.; Vanmarcke, H.; Ponsard, B.; Lahoutte, T.; Luxen, A.; Baatout, S. Biological Carrier Molecules of Radiopharmaceuticals for Molecular Cancer Imaging and Targeted Cancer Therapy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 5218–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, B.J.; Bartlett, D.J.; McGarrah, P.W.; Lewis, A.R.; Johnson, D.R.; Berberoğlu, K.; Pandey, M.K.; Packard, A.T.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Hruska, C.B. A Review of Theranostics: Perspectives on Emerging Approaches and Clinical Advancements. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 2023, 5, e220157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragina, O.; Chernov, V.; Larkina, M.; Rybina, A.; Zelchan, R.; Garbukov, E.; Oroujeni, M.; Loftenius, A.; Orlova, A.; Sörensen, J.; et al. Phase I Clinical Evaluation of 99mTc-Labeled Affibody Molecule for Imaging HER2 Expression in Breast Cancer. Theranostics 2023, 13, 4858–4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelchan, R.; Chernov, V.; Medvedeva, A.; Rybina, A.; Bragina, O.; Mishina, E.; Larkina, M.; Varvashenya, R.; Fominykh, A.; Schulga, A.; et al. Phase I Clinical Evaluation of Designed Ankyrin Repeat Protein [99mTc]Tc(CO)3-(HE)3-Ec1 for Visualization of EpCAM-Expressing Lung Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, A.; Chernov, V.; Larkina, M.; Rybina, A.; Zelchan, R.; Bragina, O.; Varvashenya, R.; Zebzeeva, O.; Bezverkhniaia, E.; Tolmachev, V.; et al. Single-Photon Emission Computer Tomography Imaging of Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) Expression in Prostate Cancer Patients Using a Novel Peptide-Based Probe [99mTc]Tc-BQ0413 with Picomolar Affinity to PSMA: A Phase I/II Clinical Study. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2025, 8, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.W.; Edwards, K.J.; Carnazza, K.E.; Carlin, S.D.; Zeglis, B.M.; Adam, M.J.; Orvig, C.; Lewis, J.S. A Comparative Evaluation of the Chelators H 4 Octapa and CHX-A″-DTPA with the Therapeutic Radiometal 90 Y. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2016, 43, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, S.; Cheng, H.H.; Weg, E.; Kim, E.H.; Chen, D.L.; Iravani, A.; Ippolito, J.E. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen-Positron Emission Tomography (PSMA-PET) of Prostate Cancer: Current and Emerging Applications. Abdom. Radiol. 2024, 49, 1288–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernicke, A.G.; Kim, S.; Liu, H.; Bander, N.H.; Pirog, E.C. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) Expression in the Neovasculature of Gynecologic Malignancies: Implications for PSMA-Targeted Therapy. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2017, 25, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruigrok, E.A.M.; Van Vliet, N.; Dalm, S.U.; De Blois, E.; Van Gent, D.C.; Haeck, J.; De Ridder, C.; Stuurman, D.; Konijnenberg, M.W.; Van Weerden, W.M.; et al. Extensive Preclinical Evaluation of Lutetium-177-Labeled PSMA-Specific Tracers for Prostate Cancer Radionuclide Therapy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, R.L.; Hnatowich, D.J. Optimum Conditions for Labeling of DTPA-Coupled Antibodies with Technetium-99m. J. Nucl. Med. 1985, 26, 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Waghorn, P.A. Radiolabelled Porphyrins in Nuclear Medicine. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2014, 57, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y.; Teng, Z.; Lu, G. Depletion of Collagen by Losartan to Improve Tumor Accumulation and Therapeutic Efficacy of Photodynamic Nanoplatforms. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahamse, H.; Hamblin, M.R. New Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, J.; Dou, D.; Yang, L. Porphyrin Photosensitizers in Photodynamic Therapy and Its Applications. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 81591–81603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mfouo-Tynga, I.S.; Dias, L.D.; Inada, N.M.; Kurachi, C. Features of Third Generation Photosensitizers Used in Anticancer Photodynamic Therapy: Review. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 34, 102091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Ying, X.; Wu, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Han, M. Research Progress of Natural Product Photosensitizers in Photodynamic Therapy. Planta Medica 2024, 90, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiehe, A.; Senge, M.O. The Photosensitizer Temoporfin (mTHPC)—Chemical, Pre-clinical and Clinical Developments in the Last Decade. Photochem. Photobiol. 2023, 99, 356–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istomin, Y.P.; Lapzevich, T.P.; Chalau, V.N.; Shliakhtsin, S.V.; Trukhachova, T.V. Photodynamic Therapy of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grades II and III with Photolon®. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2010, 7, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Saito, S.; Inai, M.; Honda, N.; Hazama, H.; Nishikawa, T.; Kaneda, Y.; Awazu, K. Efficient Photodynamic Therapy against Drug-Resistant Prostate Cancer Using Replication-Deficient Virus Particles and Talaporfin Sodium. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, H.; Ohba, S.; Egashira, K.; Asahina, I. The Effect of Photodynamic Therapy with Talaporfin Sodium, a Second-Generation Photosensitizer, on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Series of Eight Cases. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 21, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoori, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Amin Doustvandi, M.; Mohammadnejad, F.; Kamari, F.; Gjerstorff, M.F.; Baradaran, B.; Hamblin, M.R. Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer: Role of Natural Products. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 26, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portugal, I.; Jain, S.; Severino, P.; Priefer, R. Micro- and Nano-Based Transdermal Delivery Systems of Photosensitizing Drugs for the Treatment of Cutaneous Malignancies. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, L.; Valduga, G.; Jori, G.; Reddi, E. Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptors in the Uptake of Tumour Photosensitizers by Human and Rat Transformed Fibroblasts. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002, 34, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, S.; Knap, B.; Przystupski, D.; Saczko, J.; Kędzierska, E.; Knap-Czop, K.; Kotlińska, J.; Michel, O.; Kotowski, K.; Kulbacka, J. Photodynamic Therapy—Mechanisms, Photosensitizers and Combinations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaffaglione, V.; Waghorn, P.A.; Exner, R.M.; Cortezon-Tamarit, F.; Godfrey, S.P.; Sarpaki, S.; Quilter, H.; Dondi, R.; Ge, H.; Kociok-Kohn, G.; et al. Structural Investigations, Cellular Imaging, and Radiolabeling of Neutral, Polycationic, and Polyanionic Functional Metalloporphyrin Conjugates. Bioconjug. Chem. 2021, 32, 1374–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroto, S.; Miyake, Y.; Shinokubo, H. Synthesis and Functionalization of Porphyrins through Organometallic Methodologies. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 2910–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Ramzan, M.; Qureshi, A.K.; Khan, M.A.; Tariq, M. Emerging Applications of Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins in Biomedicine and Diagnostic Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Biosensors 2018, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindev, O.; Dalantai, M.; Ahn, W.S.; Shim, Y.K. Gadolinium Complexes of Chlorin Derivatives Applicable for MRI Contrast Agents and PDT. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2009, 13, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, M.; Suvorov, N.; Ostroverkhov, P.; Pogorilyy, V.; Kirin, N.; Popov, A.; Sazonova, A.; Filonenko, E. Advantages of Combined Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Oncological Diseases. Biophys. Rev. 2022, 14, 941–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, F.; Savoie, H.; Rosca, E.V.; Boyle, R.W. PET/PDT Theranostics: Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of a Peptide-Targeted Gallium Porphyrin. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 4925–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocakoglu, K.; Bayrak, E.; Onursal, M.; Yilmaz, O.; Yurt Lambrecht, F.; Holzwarth, A.R. Evaluation of 99mTc-Pheophorbide-a Use in Infection Imaging: A Rat Model. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2011, 69, 1165–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motaleb, M.A.; Nassar, M.Y. Preparation, Molecular Modeling and Biodistribution of 99mTc-Phytochlorin Complex. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2014, 299, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, M.; Ostroverkhov, P.; Suvorov, N.; Tikhonov, S.; Popov, A.; Shelyagina, A.; Kirin, N.; Nichugovskiy, A.; Usachev, M.; Bragina, N.; et al. Potential Agents for Combined Photodynamic and Chemotherapy in Oncology Based on Pt(II) Complexes and Pyridine-Containing Natural Chlorins. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2023, 27, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.; Suvorov, N.; Kornikov, A.; Ostroverkhov, P.; Tikhonov, S.; Pogorilyy, V.; Demina, A.; Usachev, M.; Plotnikova, E.; Pankratov, A.; et al. Ytterbium Complexes with Chlorin E6 Derivatives for Targeted NIR-II Bioimaging. Macroheterocycles 2024, 17, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadwal, M.; Mittal, S.; Das, T.; Sarma, H.D.; Chakraborty, S.; Banerjee, S.; Pillai, M.R. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 177Lu-DOTA-Porphyrin Conjugate: A Potential Agent for Targeted Tumor Radiotherapy Detection. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2014, 58, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.K.; Gryshuk, A.L.; Sajjad, M.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Abouzeid, M.M.; Morgan, J.; Charamisinau, I.; Nabi, H.A.; Oseroff, A.; et al. Multimodality Agents for Tumor Imaging (PET, Fluorescence) and Photodynamic Therapy. A Possible “See and Treat” Approach. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 6286–6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Harriss, B.I.; Chan, C.-F.; Jiang, L.; Tsoi, T.-H.; Long, N.J.; Wong, W.-T.; Wong, W.-K.; Wong, K.-L. Gallium and Functionalized-Porphyrins Combine to Form Potential Lysosome-Specific Multimodal Bioprobes. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 6839–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.; Suvorov, N.; Larkina, M.; Plotnikov, E.; Varvashenya, R.; Bodenko, V.; Yanovich, G.; Ostroverkhov, P.; Usachev, M.; Filonenko, E.; et al. Novel Chlorin with a HYNIC: Synthesis, 99mTc-Radiolabeling, and Initial Preclinical Evaluation. Molecules 2024, 30, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, D.; Cornelissen, B. Emerging Chelators for Nuclear Imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 63, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choppin, G.R.; Thakur, P.; Mathur, J.N. Thermodynamics and the Structure of Binary and Ternary Complexation of Am3+ Cm3+ and Eu3+ with DTPA and DTPA + IDA. Comptes Rendus. Chim. 2007, 10, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.-D.; Park, K.B.; Jang, B.-S.; Choi, S.-J.; Choi, S.M.; Kim, Y.-M. Holmium-166-DTPA as a Liquid Source for Endovascular Brachytherapy. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2002, 29, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, C.E.; Ichiki, W.A.; Ruiz, M.F.D.C.M.; Santos, A.O.; Etchebehere, E.C.S.D.C. 99mTc-DISIDA Uptake in Liver Lesion and Pulmonary Metastases Shown on SPECT/CT in a Patient with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2014, 39, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veteläinen, R.L.; Bennink, R.J.; De Bruin, K.; Van Vliet, A.; Van Gulik, T.M. Hepatobiliary Function Assessed by 99mTc-Mebrofenin Cholescintigraphy in the Evaluation of Severity of Steatosis in a Rat Model. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2006, 33, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaife, M.A.; Dirksen, J.W.; McIntire, R.H.; Harned, R.K.; Anderson, J.; Williams, S. The Clinical Usefulness of 99mTc-PIPIDA in the Study of Hepatobiliary Disease. RadioGraphics 1982, 2, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Xiao, X.; Dai, X.; Duan, Z.; Pan, D.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Luo, K.; Gong, Q. Cross-Linked and Biodegradable Polymeric System as a Safe Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agent. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 1575–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.; Thomas, R.G.; Heo, S.; Park, M.-S.; Bae, W.K.; Heo, S.H.; Yim, N.Y.; Jeong, Y.Y. A Hyaluronic Acid-Conjugated Gadolinium Hepatocyte-Specific T1 Contrast Agent for Liver Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2015, 17, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazari, P.P.; Shukla, G.; Goel, V.; Chuttani, K.; Kumar, N.; Sharma, R.; Mishra, A.K. Synthesis of Specific SPECT-Radiopharmaceutical for Tumor Imaging Based on Methionine: 99mTc-DTPA-Bis(Methionine). Bioconjug. Chem. 2010, 21, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Repo, E.; Sillanpää, M.; Meng, Y.; Yin, D.; Tang, W.Z. Green Synthesis of Magnetic EDTA- and/or DTPA-Cross-Linked Chitosan Adsorbents for Highly Efficient Removal of Metals. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, R.; Oishi, S.; Ohno, H.; Kimura, H.; Saji, H.; Fujii, N. Concise Site-Specific Synthesis of DTPA–Peptide Conjugates: Application to Imaging Probes for the Chemokine Receptor CXCR4. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 3216–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, D.; Shukla, G.; Chuttani, K.; Chandra, H.; Mishra, A.K. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 99mTc-DTPA-Bis(His) as a Potential Probe for Tumor Imaging with SPECT. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2009, 24, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezverkhniaia, E.; Kanellopoulos, P.; Abouzayed, A.; Larkina, M.; Oroujeni, M.; Vorobyeva, A.; Rosenström, U.; Tolmachev, V.; Orlova, A. Preclinical Evaluation of a Novel High-Affinity Radioligand [99mTc]Tc-BQ0413 Targeting Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodman, C.A.; Keeffe, E.B.; Lieberman, D.A.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Krishnamurthy, G.T.; Gilbert, S.; Eklem, M.J. Diagnosis of Sclerosing Cholangitis with Technetium 99m-Labeled Iminodiacetic Acid Planar and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomographic Scintigraphy. Gastroenterology 1987, 92, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiotellis, E.; Subramanian, G.; McAfee, J.G. Preparation of Tc-99m Labeled Pyridoxal-Amino Acid Complexes and Their Evaluation. Int. J. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1977, 4, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervu, L.R.; Joseph, J.A.; Chun, S.B.; Rolleston, R.E.; Synnes, E.I.; Thompson, L.M.; Aldis, A.E.; Rosenthall, L. Evaluation of Six New 99mTc-IDA Agents for Hepatobiliary Imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1988, 14, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, G.T.; Turner, F.E. Pharmacokinetics and Clinical Application of Technetium 99m-Labeled Hepatobiliary Agents. Semin. Nucl. Med. 1990, 20, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowicz-Piasecka, M.; Dębski, P.; Mikiciuk-Olasik, E.; Sikora, J. Synthesis and Biocompatibility Studies of New Iminodiacetic Acid Derivatives. Molecules 2017, 22, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilcock, C.; Ahkong, Q.F.; Fisher, D. 99mTc-Labeling of Lipid Vesicles Containing the Lipophilic Chelator PE-DTTA: Effect of Tin-to-Chelate Ratio, Chelate Content and Surface Polymer on Labeling Efficiency and Biodistribution Behavior. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1994, 21, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, F.; Sadeghzadeh, N. Tumor Targeting with 99mTc Radiolabeled Peptides: Clinical Application and Recent Development. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2019, 93, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duatti, A. Review on 99mTc Radiopharmaceuticals with Emphasis on New Advancements. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2021, 92, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, W. Contrast Agents. In Topics in Current Chemistry; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005; ISBN 978-3-540-22577-5. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto, R.; Schibli, R.; Waibel, R.; Abram, U.; Schubiger, A.P. Basic Aqueous Chemistry of [M(OH2)3(CO)3]+ (M = Re, Tc) Directed towards Radiopharmaceutical Application. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 190–192, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piramoon, M.; Jalal Hosseinimehr, S. The Past, Current Studies and Future of Organometallic 99mTc(CO)3 Labeled Peptides and Proteins. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 4854–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkina, M.; Plotnikov, E.; Bezverkhniaia, E.; Shabanova, Y.; Tretyakova, M.; Yuldasheva, F.; Zelchan, R.; Schulga, A.; Konovalova, E.; Vorobyeva, A.; et al. Comparative Preclinical Evaluation of Peptide-Based Chelators for the Labeling of DARPin G3 with 99mTc for Radionuclide Imaging of HER2 Expression in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaxton, C.S.; Rink, J.S.; Naha, P.C.; Cormode, D.P. Lipoproteins and Lipoprotein Mimetics for Imaging and Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 106, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.V.; Reshetnickov, A.V.; Ponomarev, G.V. One more PDT application of chlorin e6. In Optical Methods for Tumor Treatment and Detection: Mechanisms and Techniques in Photodynamic Therapy IX, Proceedings of the BiOS 2000 the International Symposium on Biomedical Optics, San Jose, CA, USA, 22–28 January 2000; SPIE: Bellevue, WA, USA, 2000; Volume 3909, pp. 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Li, G.; Kanter, P.; Lamonica, D.; Grossman, Z.; Pandey, R.K. Bifunctional HPPH-N2S2-99mTc Conjugates as Tumor Imaging Agents: Synthesis and Biodistribution Studies. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2003, 7, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleria, M.; Das, T.; Vats, K.; Amirdhanayagam, J.; Mathur, A.; Sarma, H.D.; Dash, A. Preparation and Evaluation of 99mTc-Labeled Porphyrin Complexes Prepared Using PNP and HYNIC Cores: Studying the Effects of Core Selection on Pharmacokinetics and Tumor Uptake in a Mouse Model. MedChemComm 2019, 10, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez De Pinillos Bayona, A.; Mroz, P.; Thunshelle, C.; Hamblin, M.R. Design Features for Optimization of Tetrapyrrole Macrocycles as Antimicrobial and Anticancer Photosensitizers. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017, 89, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidfar, N.; Jalilian, A. An Overview of Labeled Porphyrin Molecules in Medical Imaging. Recent Pat. Top. Imaging 2015, 5, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarem, A.; Klika, K.D.; Litau, G.; Remde, Y.; Kopka, K. HBED-NN: A Bifunctional Chelator for Constructing Radiopharmaceuticals. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 7501–7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, B.T.; Davis, T.P. The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005, 57, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Razzak, R.; Florence, G.J.; Gunn-Moore, F.J. Approaches to CNS drug delivery with a focus on transporter-mediated transcytosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, T.V.; Koh, G.Y. Biological functions of lymphatic vessels. Science 2020, 369, eaax4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnier, L.; Gkountidi, A.O.; Hugues, S. Tumor-associated lymphatic vessel features and immunomodulatory functions. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrantuono, E.; Ghibaudi, M.; Matias, D.; Battaglia, G. The multifaceted therapeutical role of low-density lipoprotein receptor family in high-grade glioma. Mol. Oncol. 2024, 18, 2966–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, A.C. Tumor endothelial cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palikuqi, B.; Nguyen, D.H.T.; Li, G.; Schreiner, R.; Pellegata, A.F.; Liu, Y.; Redmond, D.; Geng, F.; Lin, Y.; Gomez-Salinero, J.M.; et al. Adaptable haemodynamic endothelial cells for organogenesis and tumorigenesis. Nature 2020, 585, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Li, X.; Dong, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Shi, W.; Sun, H.; et al. Tumour vasculature at single-cell resolution. Nature 2024, 632, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Tavares, A.J.; Dai, Q.; Ohta, S.; Audet, J.; Dvorak, H.F.; Chan, W.C. Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Wu, J.; Sawa, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Hori, K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: A review. J. Control. Release 2000, 65, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaal, E.A.; Berkers, C.R. The influence of metabolism on drug response in cancer. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinimehr, S.J.; Farzipour, S.; Alvandi, M.; Shaghaghi, Z. Effect of using different co-ligands during 99mTc-labeling of J18 peptide on SK-MES-1 cell binding and tumor targeting. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2021, 24, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Hong, Y.; Kimura, R.H.; Ma, X.; Liu, H.; Qin, C.; Hu, X.; Hayes, T.R.; Benny, P.; et al. 99mTc-labeled cystine knot peptide targeting integrin αvβ6 for tumor SPECT imaging. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kit | Kit Components | Labelling Conditions | Compound | Radiochemical Yield, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation Temperature, °C | Incubation Time, min | 99mTc-Labelled Chlorin + RHT (System A) | RHT (System B) | |||

| 1 | Tin (II) chloride (75 µg, 0.01 M in HCl, Fluka Chemika, Switzerland); sodium gluconate (5 mg, 50 mg/mL in Milli-Q water) | 60 | 60 | [99mTc]Tc-4Ac | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

| [99mTc]Tc-4Ac3N | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | ||||

| [99mTc]Tc-3Ac3N2Chl | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ±0.2 | ||||

| 2 | Tin (II) chloride (75 μg, 0.01 M in HCl); sodium gluconate (5 mg, 50 mg/mL in Milli-Q water); tetrasodium EDTA (100 μg, 1 mg/mL in PBS) | [99mTc]Tc-4Ac | 92.3 ± 5.4 | 80.8 ± 4.2 | ||

| [99mTc]Tc-4Ac3N | 96.2 ± 4.2 | 76.4 ± 5.1 | ||||

| [99mTc]Tc-3Ac3N2Chl | 57.4 ± 3.8 | 94.2 ± 5.2 | ||||

| 3 | Tin (II) chloride (50 µg, 4 mg/mL in 99.0% ethanol); ascorbic acid (25 µg, 2 mg/mL) | [99mTc]Tc-4Ac | 23.0 ± 3.1 | 12.4 ± 3.7 | ||

| [99mTc]Tc-4Ac3N | 65.0 ± 5.2 | 40.3 ± 5.6 | ||||

| [99mTc]Tc-3Ac3N2Chl | 63.0 ± 1.6 | 64.3 ± 2.4 | ||||

| 4 | Tin (II) chloride (75 µg, 4 mg/mL in 0.1 M HCl); trisodium citrate (5 µL, 0.1 M) | 60 | 60 | [99mTc]Tc-4Ac | 19.6 ± 3.5 | 92.3 ± 1.1 |

| [99mTc]Tc-4Ac3N | 32.2 ± 4.2 | 22.3 ± 2.1 | ||||

| [99mTc]Tc-3Ac3N2Chl | 22.2 ± 1.4 | 18.3 ± 3.5 | ||||

| 85 | 60 | [99mTc]Tc-4Ac | 6.1 ± 0.5 | 16.9 ± 5.4 | ||

| [99mTc]Tc-4Ac3N | 9.7 ± 2.6 | 22.7 ± 2.3 | ||||

| [99mTc]Tc-3Ac3N2Chl | 18.3 ± 1.9 | 39.3 ± 1.0 | ||||

| 70 | 30 | [99mTc]Tc-4Ac | 6.3 ± 2.0 | 8.7 ± 0.5 | ||

| [99mTc]Tc-4Ac3N | 60.7 ± 4.2 | 36.3 ± 2.8 | ||||

| [99mTc]Tc-3Ac3N2Chl | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 40.4 ± 1.5 | ||||

| Labelling Conditions | Radiochemical Yield, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature, ◦C | Time, min | [99mTc]Tc(CO)3-4Ac | [99mTc]Tc(CO)3-4Ac3N | [99mTc]Tc(CO)3-3Ac3N2Chl |

| 60 | 30 | 27.3 ± 5.7 | 37.5 ± 3.2 | 19.3 ± 4.6 |

| 60 | 25.8 ± 3.7 | 27.3 ± 5.7 | 15.1 ± 3.4 | |

| 80 | 30 | 7.5 ± 2.8 | 10.3 ± 2.4 | 9.7 ± 3.2 |

| 60 | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 7.3 ± 2.3 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | |

| Radiocomplex | Conditions | Radiochemical Purity, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After Labelling | After the In Vitro Stability Test | |||||

| 1 h | 2 h | 4 h | 6 h | |||

| [99mTc]Tc(CO)3-4Ac | 1000-fold molar excess of histidine | 93 ± 1 | 93 ± 1 | 93 ± 1 | 92 ± 0.5 | 91 ± 2 |

| PBS | 92 ± 1.2 | 92 ± 1 | 91 ± 1 | 90 ± 1.5 | ||

| [99mTc]Tc(CO)3-4Ac3N | 1000-fold molar excess of histidine | 94 ± 1 | 94 ± 0.7 | 92 ± 1 | 91 ± 1 | 90 ± 2 |

| PBS | 91 ± 1 | 91 ± 1.5 | 90 ± 1 | 90 ± 2 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Larkina, M.; Demina, A.; Suvorov, N.; Ostroverkhov, P.; Plotnikov, E.; Varvashenya, R.; Bodenko, V.; Yanovich, G.; Prach, A.; Pogorilyy, V.; et al. Evaluation of the Functional Suitability of Carboxylate Chlorin e6 Derivatives for Use in Radionuclide Diagnostics. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010023

Larkina M, Demina A, Suvorov N, Ostroverkhov P, Plotnikov E, Varvashenya R, Bodenko V, Yanovich G, Prach A, Pogorilyy V, et al. Evaluation of the Functional Suitability of Carboxylate Chlorin e6 Derivatives for Use in Radionuclide Diagnostics. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleLarkina, Mariia, Anastasia Demina, Nikita Suvorov, Petr Ostroverkhov, Evgenii Plotnikov, Ruslan Varvashenya, Vitalina Bodenko, Gleb Yanovich, Anastasia Prach, Viktor Pogorilyy, and et al. 2026. "Evaluation of the Functional Suitability of Carboxylate Chlorin e6 Derivatives for Use in Radionuclide Diagnostics" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010023

APA StyleLarkina, M., Demina, A., Suvorov, N., Ostroverkhov, P., Plotnikov, E., Varvashenya, R., Bodenko, V., Yanovich, G., Prach, A., Pogorilyy, V., Tikhonov, S., Popov, A., Usachev, M., Volel, B., Vasil’ev, Y., Belousov, M., & Grin, M. (2026). Evaluation of the Functional Suitability of Carboxylate Chlorin e6 Derivatives for Use in Radionuclide Diagnostics. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010023