Experimental and Modeling-Based Approaches for Mechanistic Understanding of Pan Coating Process—A Detailed Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

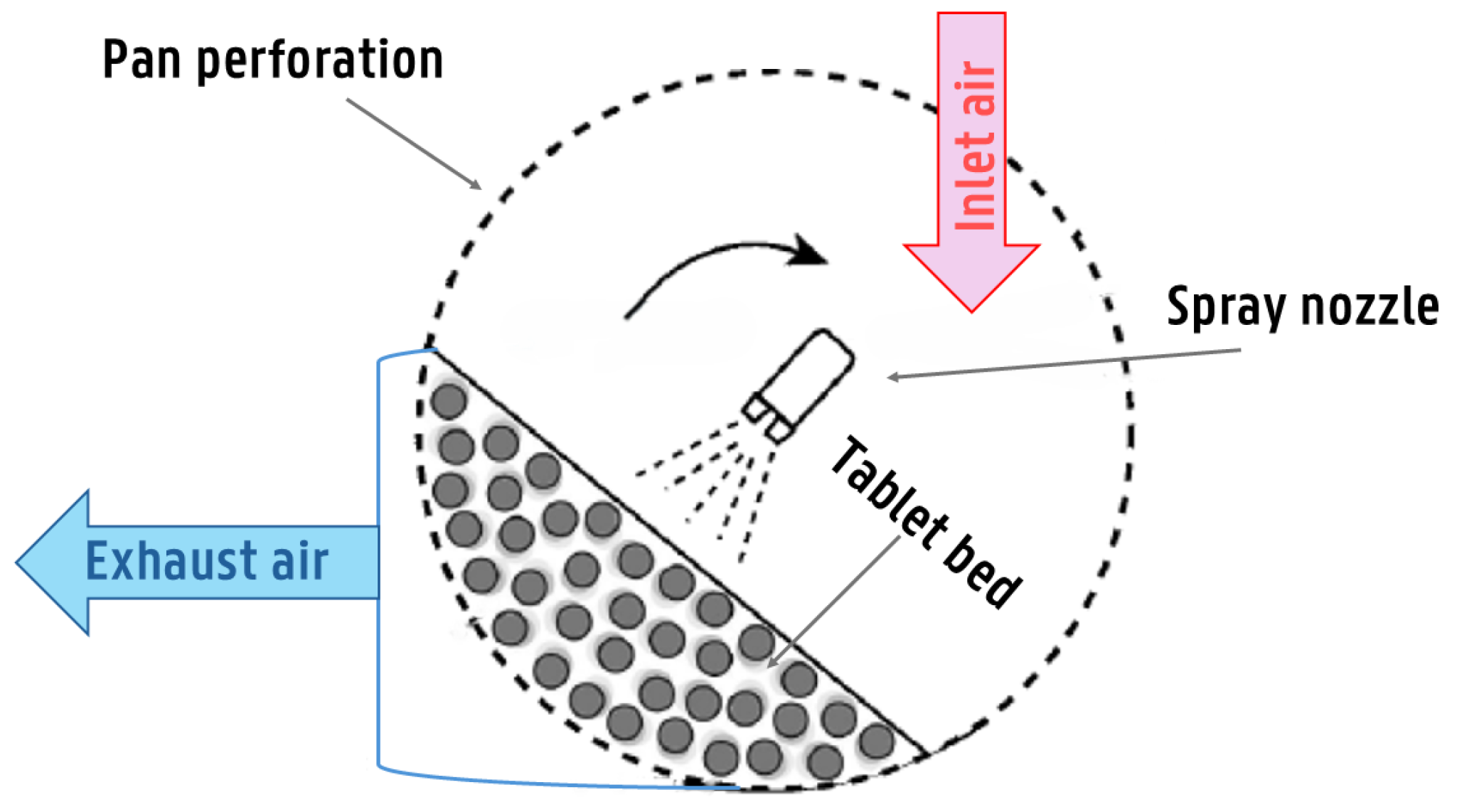

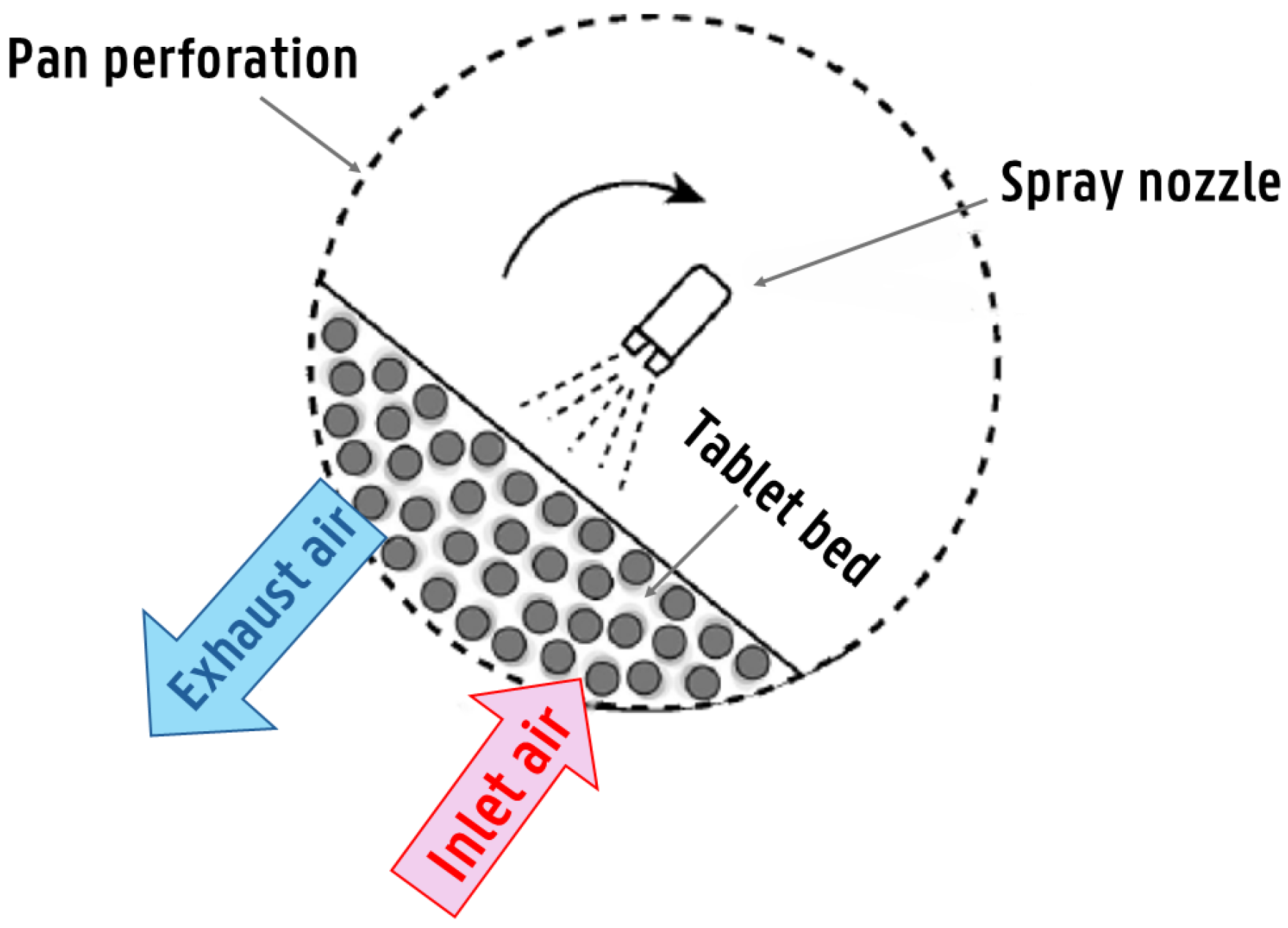

2. Tablet Coating Equipment and Process Operation Modes

2.1. Different Types of Coaters and Their Specifications

2.2. Coating Processes

2.2.1. Batch Mode

2.2.2. Continuous Mode

- High throughput rate (up to 1000 to 2000 kg/h) [14];

- Reduced product exposure to severe process conditions (heat, moisture, and mechanical stress) due to shorter processing time [14];

- Enabling implementation of real-time sensor and in-line quality control measurements [15];

- Tablets spend more time on the surface due to the shallower tablet bed [15].

2.2.3. Semi-Continuous

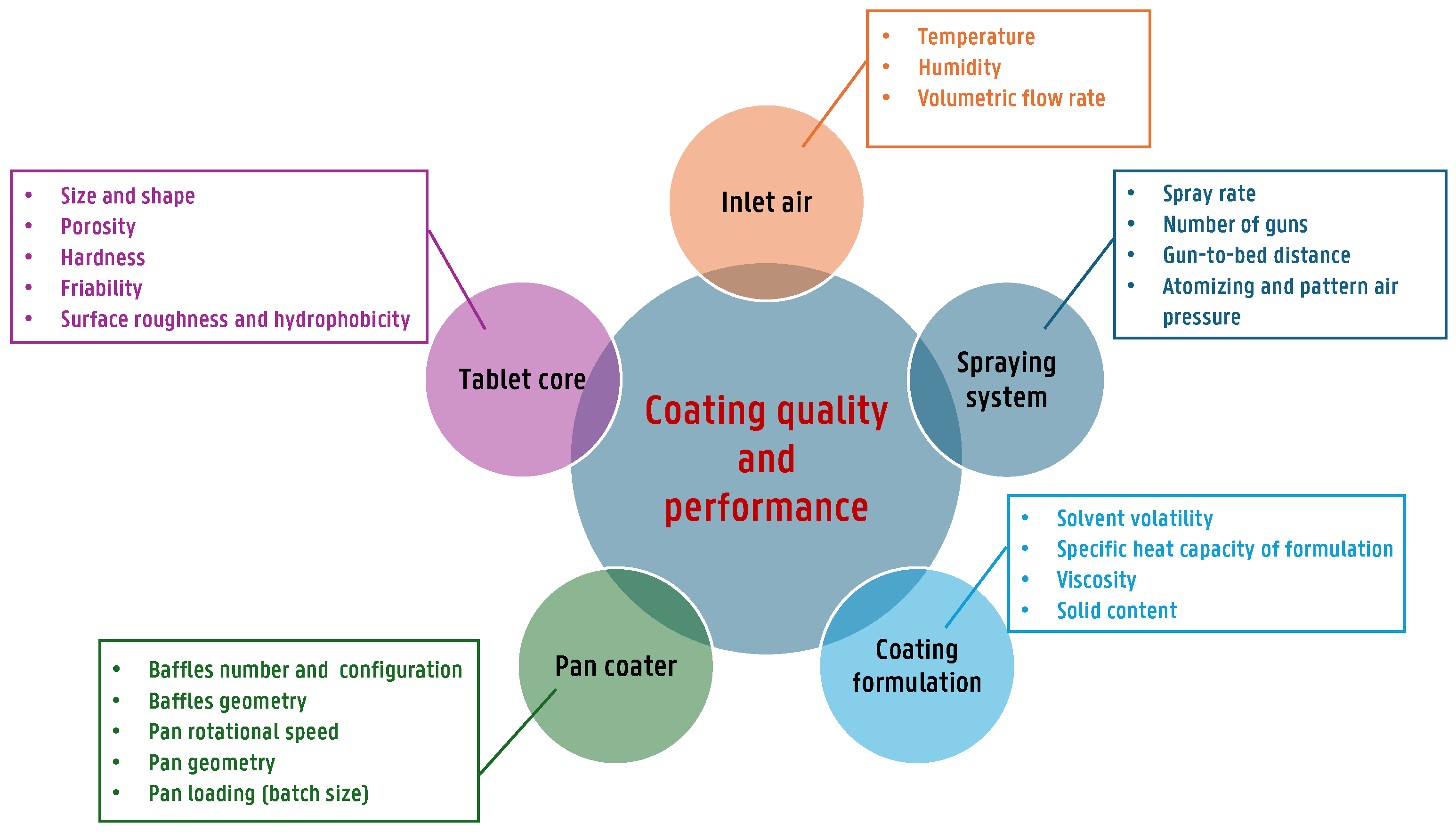

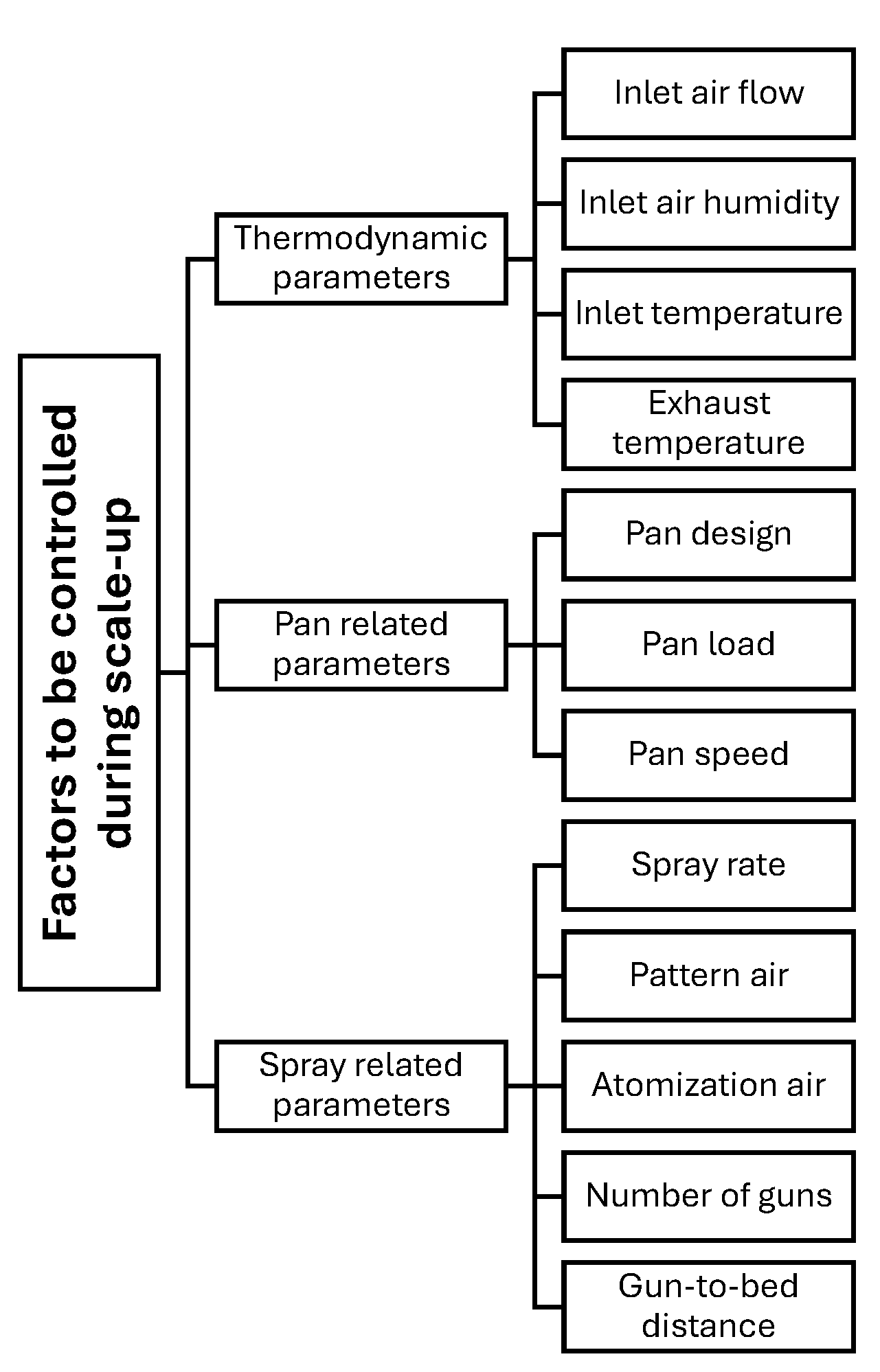

3. Key Process Parameters and Their Impact on the Coating Quality

3.1. Coating Critical Factors—A Way to Control Coating Quality

3.1.1. Coating Formulation Factors

3.1.2. Air Parameters Determining Evaporative Performance

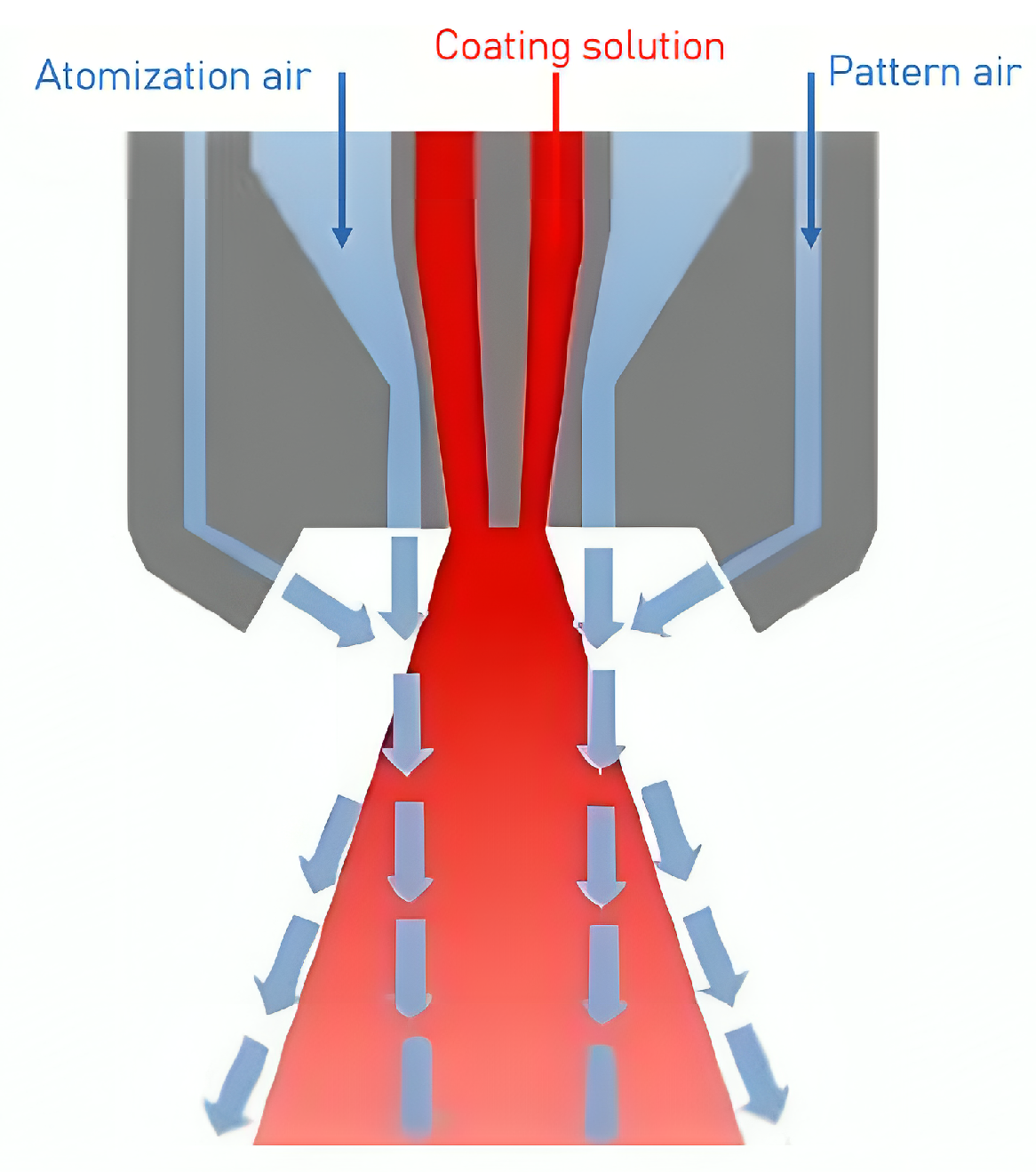

3.1.3. Uniformity of the Spray Application

3.1.4. Uniformity of Tablet Movement

- Pan speed:An optimal pan speed is essential to ensure uniform tablet movement, which in turn results in a uniform coating distribution. In general, the highest pan speed that does not cause defects such as tablet breakage or sticking should be used to enhance mixing and reduce coating variability. It is important to continuously monitor and adjust tablet movement throughout the coating process, as the application of the coating alters the tablet surface, increasing the degree of slip of the tablets and potentially affecting movement dynamics [23].

- Baffle design and number:Mixing baffles are primarily designed to enhance both axial and radial mixing by guiding tablet movement between the front and back sections of the coating pan and promoting tumbling throughout the bed. As baffles pass through the tablet bed, they temporarily lift portions of the tablets, creating a wave-like surface across the bed. Depending on the position of the spray gun relative to the peaks and troughs of the lifted tablet surface, the gun-to-bed distance can either increase or decrease. Maintaining minimal fluctuations in this gun-to-bed distance is crucial to ensure that the spray consistently travels the same path, allowing spray droplets to reach the tablets with uniform moisture levels [23]. Chen et al. [42] investigated the impact of baffle shapes on tablet movement dynamics and, consequently, coating uniformity. To achieve this, they compared three different cases: without baffles, Xiaolun™ baffles, and a self-designed baffle that is flatter and shorter. They demonstrated that the cases with baffles present better coating uniformity compared to the case without baffles. Comparing the two different baffle shapes revealed that the self-designed baffle provides more uniform coating. This is explained by the higher tablet velocity, which promotes sufficiently frequent and more uniform passage through the spray zone, and therefore leads to more uniform coating [42].

3.1.5. Tablet Shape

3.2. Using Retrospective Data to Select Critical Process Parameters

3.3. Using DOE to Select Critical Process Parameters

4. Modeling of the Film Coating Process

4.1. Thermodynamic Modeling

4.1.1. Principles of Thermodynamic Modeling and Model Validation

Mass and Energy Balance Equations

Mass Transfer

Heat Transfer

Heat Loss to the Drum and Environment

4.1.2. Overview of Thermodynamic Models and Their Advancements

Incorporating Experimental Heat Loss Factor ()

Zonal Division for Enhanced Intra-Bed Variability Representation

Balancing Complexity: Incorporating Heat Loss and Lumped Parameter Modeling

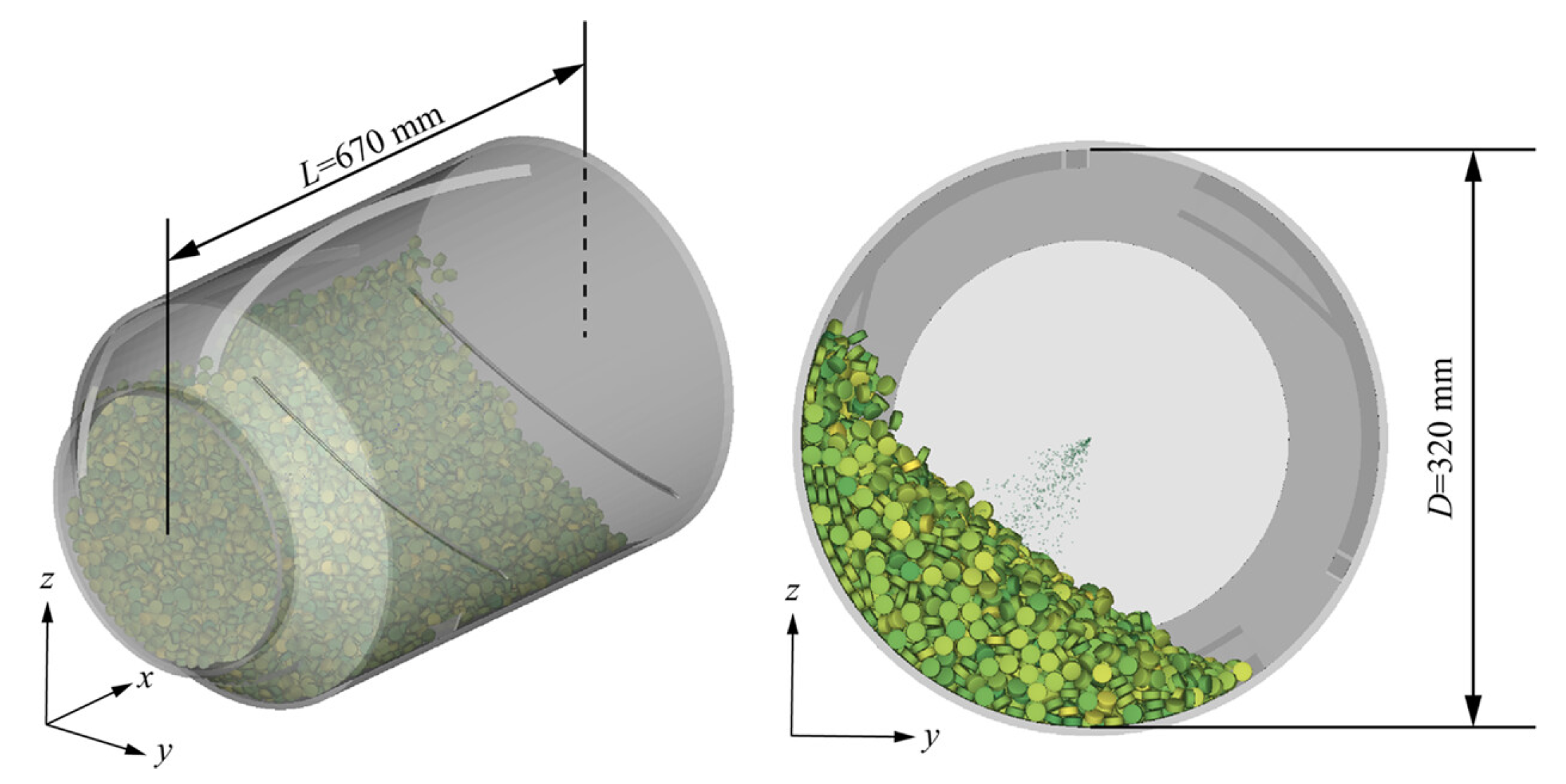

4.2. Discrete Element Method Modeling

4.3. Population Balance Modeling

- There is a constant exchange rate of particles between these regions;

- There is uniform spraying, and the quantity of deposited coating is linked to the duration the particle remains within the spray zone;

- The probability of exchange for a particle with a specific coating amount is linked to the number of particles with the same amount of coating within that region.

Compartmental Population Balance Modeling

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Modeling Approaches

5. Spray Atomization and Droplet Drying in Transit to the Tablet Bed

5.1. Spray Droplet Size Modeling

5.2. Influence of Operational and Material Parameters on Atomization and Droplet Size

5.3. Spray Drying Model

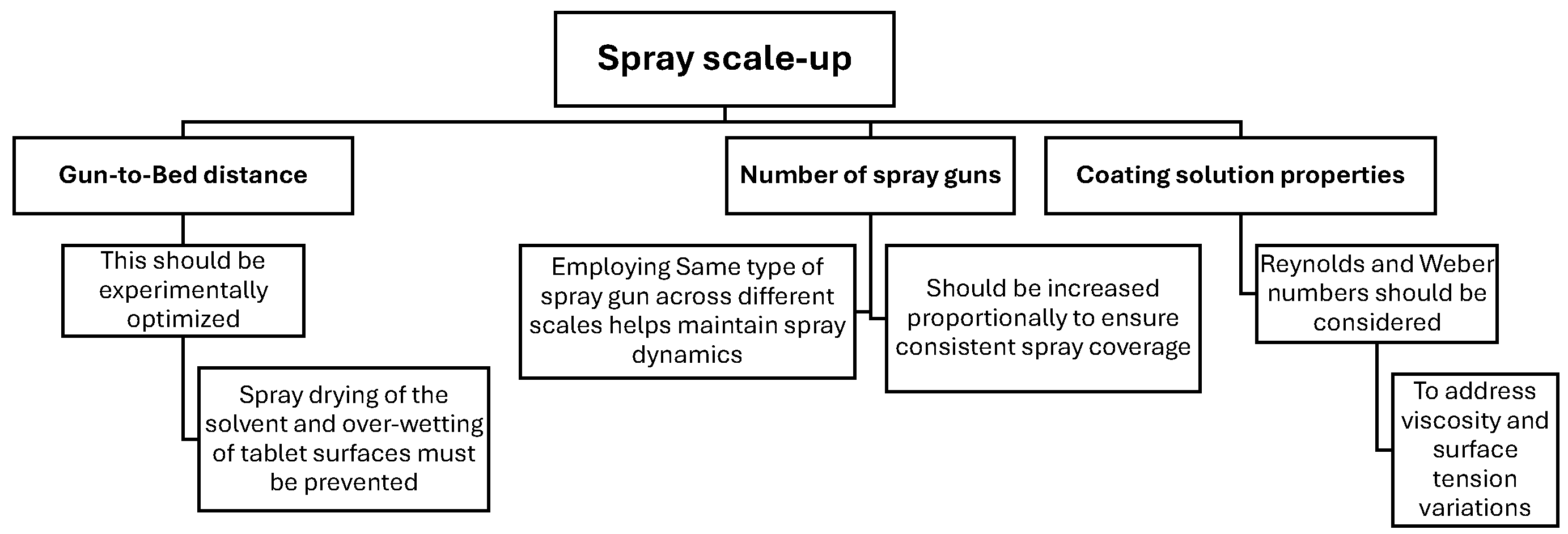

6. Pan Coating Scale-Up Approaches

- Geometric similarity ensures that all proportional relationships between dimensions remain the same across different scales.

- Dynamic similarity involves maintaining the balance of forces governing tablet motion, such as inertial and gravitational forces.

- Kinematic similarity ensures that velocity ratios at corresponding points in the pan remain consistent across scales.

- Macroscopic approach: considers large-scale factors like heat and mass transfer, pan geometry, and spray rate to ensure consistent conditions across different scales.

- Microscopic approach: focuses on local interactions, such as how droplets interact within the spray zone and how tablets move, aiming to improve coating uniformity at a more precise level.

6.1. Geometric Similarity-Pan Load

6.2. Dynamic Similarity-Pan Speed

6.3. Kinematic Similarity—Tablet Velocity and Spray Kinetics

6.3.1. Spray Dynamics

6.3.2. Coating Time

7. Data Collection and Process Analytical Technologies

7.1. Data Logging to Understand Thermodynamic Micro-Environment

7.2. Process Analytical Technologies

7.2.1. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy

| Measurement | CQAs | Reference Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-line | Real-time endpoint detection of coating process | - | [126] |

| At-line/In-line/Off-line/On-line | Coating thickness | Optical microscopy | [127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135] |

| NIR chemical imaging | Coating thickness Coating defects | Terahertz pulsed imaging | [136,137] |

| Off-line | API distribution uniformity | - | [138] |

| NIR chemical imaging (NIR-HSI) | API content Amount of coating in coated tablet | HPLC UV-spectroscopy | [139] |

| In-line | Moisture content Coating percent | Loss on drying Weight gain | [140] |

| In-line | Weight gain of tablet | micro-CT (correlated with coating thickness) | [141] |

| Off-line | Color uniformity Coating uniformity Real-time endpoint detection of coating process | Optical microscopy Weight gain | [135] |

| On-line | Moisture absorption rate Coating Weight gain | Gravimetric analysis Weight gain | [142] |

| At-line/Off-line | Drug release rate | Dissolution test | [128,131,132] |

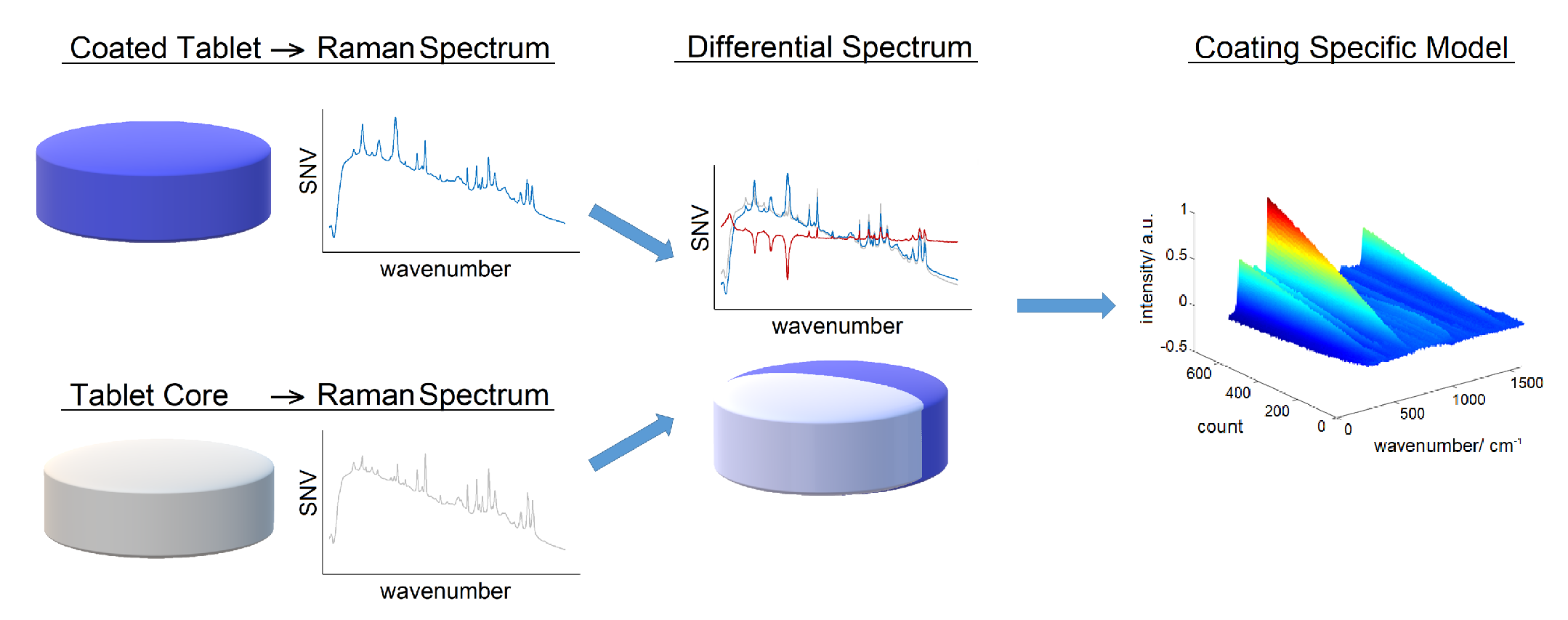

7.2.2. Raman Spectroscopy

| Mode of Operation | CQAs | Reference Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| At-line | Coating thickness | Coating time | [150] |

| Digital micrometer | [151] | ||

| Weight gain | [152] | ||

| Optical microscopy | [129] | ||

| In-line | Coating thickness | Terahertz pulsed imaging | [153] |

| Geometric model calculation | [148,154] | ||

| Weight gain | [146] | ||

| In-line | Drug release | Dissolution test | [153] |

| In-/off-line | Coating thickness Drug content | Optical microscopy HPLC | [155] |

| On-line | Coating thickness | Optical microscopy | [156] |

7.2.3. Terahertz Pulsed Imaging

7.2.4. Image Analysis

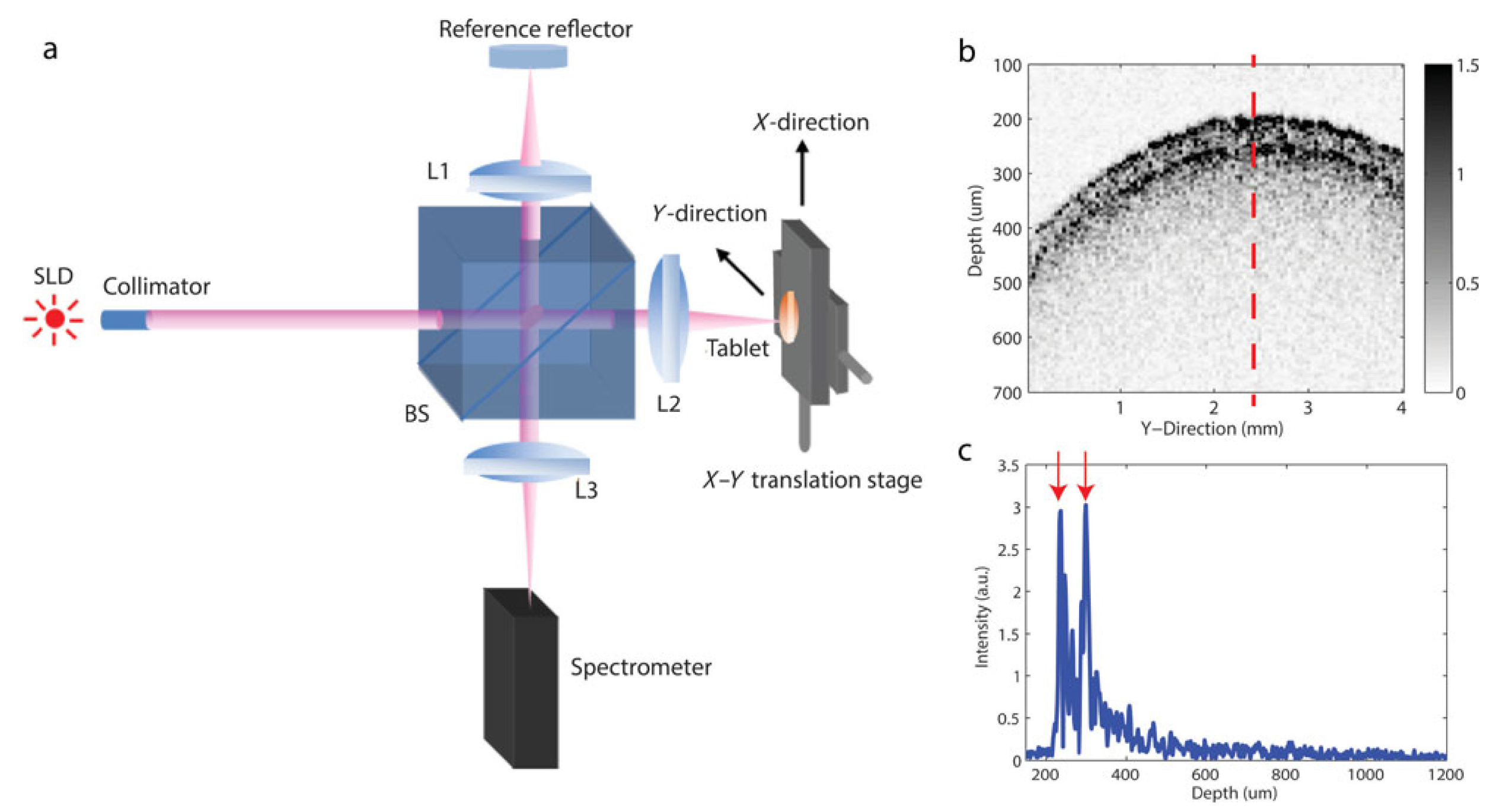

7.2.5. Optical Coherence Tomography

8. Summary and Future Perspectives

- How can existing sub-models (particle dynamics, spray dynamics, thermodynamics) be integrated into a unified, predictive coating model?

- What methodologies should be used in model development, calibration, and validation to ensure applicability across different coater types and scales?

- How can machine learning and data-driven approaches be developed for analyzing historical data? This can reveal the interplay between process parameters and product quality, support decision making for future coating processes, and lead toward predictive modeling

- What role can advanced tools play in enabling in-line and real-time monitoring, as well as in better capturing inter-tablet and intra-tablet coating variability?

- How can mechanistic modeling and -based approaches be extended to facilitate understanding of the correlations between process parameters and critical quality attributes, CQAs?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| AA | Atomization air flow rate |

| Circular area of inner ribbon covered by tablets (m2) | |

| Surface area of the film (m2) | |

| Surface area of the drum through which heat is lost (m2) | |

| A | Surface area over which heat transfer occurs (m2) |

| Spalding number | |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CQAs | Critical quality attributes |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| Drag coefficient of the droplet | |

| Concentration of solvent in the gas phase (kg·m−3) | |

| Specific heat capacity of solvent in coating solution (J·kg−1 · K−1) | |

| Specific heat capacity of water (J/kg·K) | |

| Concentration of solvent in the film interface (kg·m −3) | |

| Empirical constant in the atomization correlation | |

| Empirical constant in the atomization correlation | |

| Specific heat capacity of gas (=air) (J/kg·K) | |

| DDM | Discrete drop method |

| DEM | Discrete element method modeling |

| Diameter of the liquid nozzle | |

| D | Pan diameter (m) |

| EE | Environmental equivalency |

| Froude number | |

| G | Growth rate of coating mass |

| HLF | Overall heat loss from the coater (W) |

| H | Drum length (m) |

| J | Number of spray guns |

| L | Length of the spray zone (m) |

| MC | Monte Carlo approach |

| Molar mass of the solvent (kg·mol −1) | |

| Molar mass of water (kg/mol) | |

| Mass of tablets in zone 1 (kg) | |

| Mass of tablets in zone 2 (kg) | |

| Near-infrared chemical imaging | |

| Near-infrared spectroscopy | |

| Average number of passes of a tablet under the spray gun | |

| The total number of particles in class at time t in the spray zone | |

| The total number of particles in class at time t in mixer k | |

| Total number of tablets in the bed | |

| The total number of particles in class at time t in mixer N | |

| Nusselt number of the droplet | |

| N | Total number of compartments |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| Oh | Ohnesorge number of the liquid stream |

| PAT | Process analytical technology |

| PA | Pattern air flow rate |

| PBM | Population balance modeling |

| Saturated vapor pressure of the solvent (Pa) | |

| Total pressure (Pa) | |

| Prandtl number of air | |

| Rate of particle exchange between perfect mixers | |

| Spray rate (kg/s) | |

| Overall heat loss from the coater (W) | |

| RSD | Relative standard deviation |

| Reynolds number of the air stream (based on outlet width ) | |

| Reynolds number of the droplet | |

| R | Universal gas constant (J·K−1·mol−1) |

| SMD | Sauter mean diameter of droplets |

| SR | Spray rate (kg/s) |

| Sc | Schmidt number |

| Sh | Sherwood number of the droplet |

| TPI | Terahertz Pulsed Imaging |

| Effective temperature of the gas phase (K) | |

| TG | Temperature of the gas phase (K) |

| Coating solution temperature (K) | |

| Temperature at the film interface (K) | |

| Drum temperature (K) | |

| Inlet gas temperature (K) | |

| Outlet gas temperature (K) | |

| Room (surrounding) temperature where the coater is located (K) | |

| Average temperature of the droplet (K) | |

| Temperature of the droplet (K) | |

| Spraying duration (s) | |

| Temperature at the tablet surface (K) | |

| T | Temperature (K) |

| Lumped mass transfer coefficient, product of evaporative | |

| surface area and mass transfer coefficient (kg·s−1) | |

| U | Overall heat transfer coefficient (W·m−2·K−1) |

| Volume of tablets between ribbons (m3) | |

| Air velocity (m/s) | |

| Droplet velocity (m/s) | |

| V | Velocity of the tablet in the spray zone (m/s) |

| Weber number of the liquid stream (based on nozzle diameter ) | |

| Concentration of coating solution (kg/kg) | |

| Solvent fraction in the coating solution | |

| Latent heat of vaporization of the solvent (J/kg) | |

| Time delay between pulse reflections at the coating surface and coating–core interface (s) | |

| Convective heat transfer coefficient between gas and tablet bed (W·m−2·K−1) | |

| Lumped convective heat transfer coefficient between gas and tablet bed (W·m−2·K−1) | |

| Fraction of particles present in the cascading zone | |

| Mass flow rate of coating solution (kg/s) | |

| Mass flux between the film and the gas phase (kg·s−1) | |

| Inlet gas mass flow rate (kg/s) | |

| Heat flux from the gas phase to the tablet bed (W) | |

| CSTR | Continuous stirred-tank reactor |

| RH | Relative humidity of the drying air |

| Dynamic viscosity of air (Pa·s) | |

| Surface fraction of solvent in the film | |

| Population density of tablets in the spray zone with coating mass between x and at time t | |

| Population density of tablets in the drying zone with coating mass between x and at time t | |

| Population density at the exit of spray zone | |

| Population density at the exit of mixer k of dry zone | |

| Population density at spray zone | |

| Population density at mixer k of dry zone | |

| Exchange rate of tablets between zones | |

| Population density at the start of spray zone | |

| Population density at the start of mixer k of dry zone | |

| Density of water (kg/m3) | |

| Bulk density of tablets (kg/m3) | |

| Density of the gas (air) stream | |

| Density of the liquid stream | |

| Droplet drying time (s) | |

| Tablet residence time on the bed surface (s) | |

| Time (s) | |

| Water activity of the droplet surface | |

| a | Projected area of a tablet (m2) |

| Width of the atomizing air outlet | |

| Exchange rate constant, defining the fraction of volume exchanged per drum rotation | |

| c | Speed of light (m/s) |

| d | Coating thickness (m) |

| Convective heat transfer coefficient (W/m2·K) | |

| h | shortest distance from the pan’s center to the bed surface (m) |

| Mass transfer coefficient (m·s−1) | |

| Effective drum mass (kg) | |

| Mass of solvent in the droplet (kg) | |

| Mass of water in the droplet (kg) | |

| Mass of the solvent in the film (kg) | |

| Mass flux ratio between fluid streams | |

| Fraction of particles in class at time t in the spray zone | |

| Fraction of particles in class at time t in mixer N | |

| Fraction of particles in class at time t in mixer k | |

| Fraction of particles in class at time t in mixer | |

| Pan rotation speed (rev/s or 1/s) | |

| Refractive index of the coating material | |

| Number of tablets in the spray zone | |

| Droplet radius (m) | |

| t | Total coating duration (s) |

| Vapor mass fraction in the bulk gas | |

| Vapor mass fraction at the droplet surface |

References

- Seo, K.S.; Bajracharya, R.; Lee, S.H.; Han, H.K. Pharmaceutical application of tablet film coating. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turton, R. Challenges in the modeling and prediction of coating of pharmaceutical dosage forms. Powder Technol. 2008, 181, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muliadi, A.; Sojka, P.E. A review of pharmaceutical tablet spray coating. At. Sprays 2010, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toschkoff, G.; Khinast, J.G. Mathematical modeling of the coating process. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 457, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GEA. ConsiGma Continuous Tablet Coater. Available online: https://www.gea.com/en/products/tablet-presses/tablet-coaters/consigma-continuous-tablet-coater/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Kemp, I.C.; Iler, L.; Waldron, M.; Turnbull, N. Modeling, experimental trials, and design space determination for the GEA ConsiGma™ coater. Dry. Technol. 2019, 37, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehling, P.; Jacevic, D.; Detobel, F.; Holman, J.; Wareham, L.; Metzger, M.; Khinast, J.G. Validating a numerical simulation of the ConsiGma (R) coater. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L.B. Bohle GmbH & Co. KG. Tablet Coaters (BTC). Available online: https://lbbohle.com/machines-processes/tablet-coating/tablet-coaters-btc/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Thomas Processing. Continuous Tablet Coating Systems. Available online: https://thomasprocessing.com/tablet-coating-systems/continuous/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Ketterhagen, W.R.; Larson, J.; Spence, K.; Baird, J.A. Predictive approach to understand and eliminate tablet breakage during film coating. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.; Hansell, J.; Nuneviller, F., III; Rajabi-Siahboomi, A.R. Evaluation of recent advances in continuous film coating processes. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2010, 36, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara Technologies. FastCoat Continuous Coating Systems (500 kg). Available online: https://www.oharatech.com/product/fastcoat-continuous-coating-systems-500-kg/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- IMA Group. CROM A Coating Machine for Pharmaceuticals. Available online: https://ima.it/pharma/machine/croma/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Porter, S.C. Coating of pharmaceutical dosage forms. In Remington; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 551–564. [Google Scholar]

- Galata, D.L.; Peterfi, O.; Ficzere, M.; Szabó-Szocs, B.; Szabo, E.; Nagy, Z.K. The current state-of-the art in pharmaceutical continuous film coating—A review. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 669, 125052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhling, P.; Jajcevic, D.; Detobel, F.; Holman, J.; Wareham, L.; Metzger, M.; Khinast, J. Validating a numerical simulation of the ConsiGma® semi-continuous tablet coating process. Authorea Prepr. 2020, 6, 112. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, T.; Lee, S. Emerging technology for modernizing pharmaceutical production: Continuous manufacturing. In Developing Solid Oral Dosage Forms; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1031–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, S. Continuous film coating processes: A review. Tablets Capsul. 2007, 4, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Suzzi, D.; Toschkoff, G.; Radl, S.; Machold, D.; Fraser, S.D.; Glasser, B.J.; Khinast, J.G. DEM simulation of continuous tablet coating: Effects of tablet shape and fill level on inter-tablet coating variability. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 69, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barimani, S.; Tomaževič, D.; Meier, R.; Kleinebudde, P. 100% visual inspection of tablets produced with continuous direct compression and coating. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 614, 121465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teżyk, M.; Milanowski, B.; Ernst, A.; Lulek, J. Recent progress in continuous and semi-continuous processing of solid oral dosage forms: A review. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2016, 42, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.; Bindra, D.S.; Felton, L.A. Influence of process parameters on tablet bed microenvironmental factors during pan coating. Aaps Pharmscitech 2014, 15, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.; Sackett, G.; Liu, L. Development, optimization, and scale-up of process parameters: Pan coating. In Developing Solid Oral Dosage Forms; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 953–996. [Google Scholar]

- Zaid, A.N. A comprehensive review on pharmaceutical film coating: Past, present, and future. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 4613–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobiska, S.; Kleinebudde, P. Coating uniformity and coating efficiency in a Bohle Lab-Coaterusing oval tablets. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2003, 56, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.E.; Crossman, E. The influence of tablet shape and pan speed on intra-tablet film coating uniformity. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1997, 23, 1239–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterhagen, W.R. Modeling the motion and orientation of various pharmaceutical tablet shapes in a film coating pan using DEM. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 409, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freireich, B.; Wassgren, C. Intra-particle coating variability: Analysis and Monte-Carlo simulations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbag, A.; Wassgren, C. Inter-tablet coating variability: Tablet residence time variability. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 2705–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbag, A.; Wassgren, C.; Penumetcha, S.S.; Pérez-Ramos, J.D. Inter-tablet coating variability: Residence times in a horizontal pan coater. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 2881–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.M.; Pandey, P. Scale up of pan coating process using quality by design principles. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 3589–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S. The role of high-solids coating systems in reducing process costs. Tablets Capsul. 2010, 8, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, S.C.; Verseput, R.P.; Cunningham, C.R. Process optimization using design of experiments. Pharm. Technol. 1997, 21, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Chang, S.Y.; Kiang, S.; Early, W.; Paruchuri, S.; Desai, D. The measurement of spray quality for pan coating processes. J. Pharm. Innov. 2008, 3, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, J.C. Psychrometric analysis of the environmental equivalency factor for aqueous tablet coating. AAPS PharmSciTech 2009, 10, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.; Kleinebudde, P. Comparison of a laboratory and a production coating spray gun with respect to scale-up. Aaps Pharmscitech 2007, 8, E21–E31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbash, D.; Fulghum, J.E.; Yang, J.; Felton, L. A novel imaging technique to investigate the influence of atomization air pressure on film–tablet interfacial thickness. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2009, 35, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacour, B.M.; Pandey, P.; Subramanian, G.; Gao, J.Z.; Nikfar, F. Correlating bilayer tablet delamination tendencies to micro-environmental thermodynamic conditions during pan coating. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2014, 40, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P. Studies to Investigate Variables Affecting Coating Uniformity in a Pan Coating Device; West Virginia University: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, P.; Song, Y.; Turton, R. Modelling of Pan-Coating Processes for Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms. Granulation 2006, 11, 377. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, M.; Levin, M. Pharmaceutical process scale-up. In Technical Report; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Q.; Liu, J.; Jin, M.; He, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, H.; Dong, J.; Yang, G.; Zhu, J. Understanding the correlations between tablet flow dynamics and coating uniformity in a pan coater: Experiments and simulations. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freireich, B.; Ketterhagen, W.R.; Wassgren, C. Intra-tablet coating variability for several pharmaceutical tablet shapes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 2535–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galí, A.; García-Montoya, E.; Ascaso, M.; Pérez-Lozano, P.; Ticó, J.; Miñarro, M.; Suñé-Negre, J. Improving tablet coating robustness by selecting critical process parameters from retrospective data. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2016, 21, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Katakdaunde, M.; Turton, R. Modeling weight variability in a pan coating process using Monte Carlo simulations. Aaps Pharmscitech 2006, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hemenway, J.; Chen, W.; Desai, D.; Early, W.; Paruchuri, S.; Chang, S.Y.; Stamato, H.; Varia, S. An evaluation of process parameters to improve coating efficiency of an active tablet film-coating process. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 427, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Just, S.; Toschkoff, G.; Funke, A.; Djuric, D.; Scharrer, G.; Khinast, J.; Knop, K.; Kleinebudde, P. Optimization of the inter-tablet coating uniformity for an active coating process at lab and pilot scale. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 457, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rege, B.D.; Gawel, J.; Kou, J.H. Identification of critical process variables for coating actives onto tablets via statistically designed experiments. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 237, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobiska, S.; Kleinebudde, P. A simple method for evaluating the mixing efficiency of a new type of pan coater. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 224, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A.B. Pharmaceutical Process Engineering and Scale-Up Principles; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, R.C. Defects in aqueous film-coated tablets. In Aqueous Polymeric Coatings for Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Meyer, R.; Flamm, M.; Wareham, L.; Metzger, M.; Tantuccio, A.; Yoon, S. Optimization of critical quality attributes in tablet film coating and design space determination using pilot-scale experimental data. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toshev, K.; Endekovska, I.; ACKOVSKA, M.T.; Stojanovska, N.A. Optimization Study of Aqueous Film-Coating Process in the Industrial Scale Using Design of Experiments. Farmacia 2023, 71, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ende, M.T.A.; Berchielli, A. A thermodynamic model for organic and aqueous tablet film coating. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2005, 10, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.P.; Duchesne, C.; Poulin, É.; Lapointe-Garant, P.P. A dynamic model of tablet film coating processes for control system design. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2023, 174, 108251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.; Baumann, K.H.; Kleinebudde, P. Mathematical modeling of an aqueous film coating process in a Bohle Lab-Coater, Part 1: Development of the model. AAPS PharmSciTech 2006, 7, E79–E86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navrátil, O.; Kolář, J.; Zadražil, A.; Štěpánek, F. Model-based evaluation of drying kinetics and solvent diffusion in pharmaceutical thin film coatings. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 2017–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulson, J.; Richardson, J. Chemical Engineering-Particle Technology and Separation Processes; RK Butterworth: Oxford, UK, 1998; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou, C.; Sorensen, E.; García-Muñoz, S.; Mazzei, L. Mathematical modelling of water absorption and evaporation in a pharmaceutical tablet during film coating. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 175, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, T.L.; Lavine, A.S.; Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P. Introduction to Heat Transfer; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, B.; Galbraith, S.C.; Liu, H.; Park, S.Y.; Huang, Z.; O’Connor, T.; Lee, S.; Yoon, S. A thermodynamic balance model for liquid film drying kinetics of a tablet film coating and drying process. Aaps Pharmscitech 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Am Ende, M.; Herbig, S.; Korsmeyer, R.; Chidlaw, M. Osmotic drug delivery from asymmetric membrane film-coated dosage forms. Handb. Pharm. Control. Release Technol. 2000, 12, 751–785. [Google Scholar]

- Rhinehart, R.R. Nonlinear Regression Modeling for Engineering Applications: Modeling, Model Validation, and Enabling Design of Experiments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Allgaier, J.; Pryss, R. Cross-validation visualized: A narrative guide to advanced methods. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, C.J.; Oberkampf, W.L. A comprehensive framework for verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification in scientific computing. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2011, 200, 2131–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prpich, A.; am Ende, M.T.; Katzschner, T.; Lubczyk, V.; Weyhers, H.; Bernhard, G. Drug product modeling predictions for scale-up of tablet film coating—A quality by design approach. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2010, 34, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wobker, M.E.S.; Mehrotra, A.; Carter, B.H. Use of commercial data loggers to develop process understanding in pharmaceutical unit operations. J. Pharm. Innov. 2010, 5, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Bindra, D.S. Real-time monitoring of thermodynamic microenvironment in a pan coater. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Ji, J.; Subramanian, G.; Gour, S.; Bindra, D.S. Understanding the thermodynamic micro-environment inside a pan coater using a data logging device. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2014, 40, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kern, D. Process Heat Transfer; Begell House: Danbury, CN, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S.; Baumann, K.H.; Kleinebudde, P. Mathematical modeling of an aqueous film coating process in a Bohle Lab-Coater: Part 2: Application of the model. AAPS PharmSciTech 2006, 7, E87–E94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterhagen, W.; Aliseda, A.; Am Ende, M.; Berchielli, A.; Doshi, P.; Freireich, B.; Prpich, A. Modeling tablet film-coating processes. In Predictive Modeling of Pharmaceutical Unit Operations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 273–316. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Zhou, T.; Bai, R.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H. Review of CFD-DEM modeling of wet fluidized bed granulation and coating processes. Processes 2023, 11, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liao, X.; Zhao, Y. DEM-DDM investigation of the tablet coating process using different particle shape models. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 62, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, S.; Suzzi, D.; Radeke, C.; Khinast, J.G. An integrated Quality by Design (QbD) approach towards design space definition of a blending unit operation by Discrete Element Method (DEM) simulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 42, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterhagen, W.R.; am Ende, M.T.; Hancock, B.C. Process modeling in the pharmaceutical industry using the discrete element method. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 442–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellmann, J. The transverse motion of solids in rotating cylinders—Forms of motion and transition behavior. Powder Technol. 2001, 118, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toschkoff, G.; Funke, A.; Altmeyer, A.; Knop, K.; Khinast, J.; Kleinebudde, P. Evaluation of the tablets’ surface flow velocities in pan coaters. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 106, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Song, Y.; Kayihan, F.; Turton, R. Simulation of particle movement in a pan coating device using discrete element modeling and its comparison with video-imaging experiments. Powder Technol. 2006, 161, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venier, C.M.; Marquez Damian, S.; Bertone, S.E.; Puccini, G.D.; Risso, J.M.; Nigro, N.M. Discrete and continuum approaches for modeling solids motion inside a rotating drum at different regimes. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Song, C.; Li, W.; Qin, H.; Wang, Q. Numerical Simulations of Particle Motions at Continuous Rotational Speed Changes in Horizontal Rotating Drums. Processes 2022, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freireich, B.; Kumar, R.; Ketterhagen, W.; Su, K.; Wassgren, C.; Zeitler, J.A. Comparisons of intra-tablet coating variability using DEM simulations, asymptotic limit models, and experiments. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 131, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, C.; Elliott, J.A. Asymptotic limits on tablet coating variability based on cap-to-band thickness distributions: A discrete element model (DEM) study. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 172, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, K.; Liu, P.; Berchielli, A.; Doshi, P.; Saxena, U.; Khan, M.; Suryawanshi, T.; Kasat, G. Prediction of the finished tablet coating variability in pan coaters by coupling CFD-DEM and Monte Carlo simulations: Method development and validation. Powder Technol. 2024, 445, 120141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureck, H.; Govender, N.; Siegmann, E.; Boehling, P.; Radeke, C.; Khinast, J.G. Industrial scale simulations of tablet coating using GPU based DEM: A validation study. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 202, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, C.; Hemati, M.; Chulia, D.; Lanne, J.Y.; Buisson, B.; Daste, G.; Elbaz, F. A model of surface renewal with application to the coating of pharmaceutical tablets in rotary drums. Powder Technol. 2003, 130, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Freireich, B.; Wassgren, C. DEM–compartment–population balance model for particle coating in a horizontal rotating drum. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 125, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Kemp, I.; Palmer, M. A DEM-based mechanistic model for scale-up of industrial tablet coating processes. Powder Technol. 2020, 364, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehling, P.; Toschkoff, G.; Dreu, R.; Just, S.; Kleinebudde, P.; Funke, A.; Rehbaum, H.; Khinast, J. Comparison of video analysis and simulations of a drum coating process. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 104, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, E.; Chaudhuri, B. Experimental and modeling approaches in characterizing coating uniformity in a pan coater: A literature review. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2012, 17, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliseda, A.; Hopfinger, E.J.; Lasheras, J.C.; Kremer, D.; Berchielli, A.; Connolly, E. Atomization of viscous and non-Newtonian liquids by a coaxial, high-speed gas jet. Experiments and droplet size modeling. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2008, 34, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasheras, J.C.; Hopfinger, E. Liquid jet instability and atomization in a coaxial gas stream. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2000, 32, 275–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, C.M.; Lasheras, J.C.; Hopfinger, E.J. Initial breakup of a small-diameter liquid jet by a high-speed gas stream. J. Fluid Mech. 2003, 497, 405–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmottant, P. Atomisation d’un Liquide Par un Courant Gazeux. Ph.D. Thesis, Grenoble INPG, Grenoble, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; You, Y.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Y. Mechanism of inter-tablet coating variability: Investigation about the motion behavior of ellipsoidal tablets in a pan coater. Powder Technol. 2021, 379, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehling, P.; Toschkoff, G.; Knop, K.; Kleinebudde, P.; Just, S.; Funke, A.; Rehbaum, H.; Khinast, J. Analysis of large-scale tablet coating: Modeling, simulation and experiments. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 90, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toschkoff, G.; Just, S.; Funke, A.; Djuric, D.; Knop, K.; Kleinebudde, P.; Scharrer, G.; Khinast, J.G. Spray models for discrete element simulations of particle coating processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 101, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funada, T.; Joseph, D.; Yamashita, S. Stability of a liquid jet into incompressible gases and liquids. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2004, 30, 1279–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yecko, P.; Zaleski, S. Transient growth in two-phase mixing layers. J. Fluid Mech. 2005, 528, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.D.; Belanger, J.; Beavers, G. Breakup of a liquid drop suddenly exposed to a high-speed airstream. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1999, 25, 1263–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeck, T.; Li, J.; López-Pagés, E.; Yecko, P.; Zaleski, S. Ligament formation in sheared liquid–gas layers. Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 2007, 21, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pagés, E.; Dopazo, C.; Fueyo, N. Very-near-field dynamics in the injection of two-dimensional gas jets and thin liquid sheets between two parallel high-speed gas streams. J. Fluid Mech. 2004, 515, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Kleinebudde, P. Scale-down experiments in a new type of pan coater. Pharm. Ind. 2005, 67, 950–957. [Google Scholar]

- Price, P.E., Jr.; Cairncross, R.A. Optimization of single-zone drying of polymer solution coatings using mathematical modeling. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000, 78, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niblett, D.; Porter, S.; Reynolds, G.; Morgan, T.; Greenamoyer, J.; Hach, R.; Sido, S.; Karan, K.; Gabbott, I. Development and evaluation of a dimensionless mechanistic pan coating model for the prediction of coated tablet appearance. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 528, 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloth, J. Formation of enzyme containing particles by spray drying. Dep. Chem. Biochem. Eng. 2008, 8, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, P.; Turton, R.; Joshi, N.; Hammerman, E.; Ergun, J. Scale-up of a pan-coating process. Aaps Pharmscitech 2006, 7, E125–E132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okutgen, E.; Hogan, J.; Aulton, M. Effects of tablet core dimensional instability on the generation of internal stresses within film coats part I: Influence of temperature changes during the film coating process. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1991, 17, 1177–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.X.; Amidon, G.; Khan, M.A.; Hoag, S.W.; Polli, J.; Raju, G.; Woodcock, J. Understanding pharmaceutical quality by design. Aaps J. 2014, 16, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fda, U. Guidance for Industry: Q8 (R2) Pharmaceutical Development. In ICH Quality Guidelines: An Implementation Guide; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 535–577. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administrat; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Veterinary Medicine. Guidance for Industry, PAT-A Framework for Innovative Pharmaceutical Development, Manufacturing and Quality Assurance. 2004. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/pat-framework-innovative-pharmaceutical-development-manufacturing-and-quality-assurance (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Bakeev, K.A. Process Analytical Technology: Spectroscopic Tools and Implementation Strategies for the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industries; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, G.L. Residual solvents. In Specification of Drug Substances and Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 421–438. [Google Scholar]

- Tankiewicz, M.; Namieśnik, J.; Sawicki, W. Analytical procedures for quality control of pharmaceuticals in terms of residual solvents content: Challenges and recent developments. Trac Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 80, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Mohan, S. Application of process analytical technology for pharmaceutical coating: Challenges, pitfalls, and trends. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, T.; Burggraeve, A.; Fonteyne, M.; Saerens, L.; Remon, J.P.; Vervaet, C. Near infrared and Raman spectroscopy for the in-process monitoring of pharmaceutical production processes. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 417, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ich Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Pharmaceutical Development Q8(R2); ICH Expert Working Group: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Volume 23, p. 8.

- Knop, K.; Kleinebudde, P. PAT-tools for process control in pharmaceutical film coating applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 457, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.; De Beer, T.; Kumar, A. Near-infrared Spectroscopy as Process Analytical Technology in Continuous Solid Dosage Form Manufacturing. In Continuous Pharmaceutical Processing and Process Analytical Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 311–337. [Google Scholar]

- Jamrógiewicz, M. Application of the near-infrared spectroscopy in the pharmaceutical technology. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012, 66, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, Y. Near-infrared spectroscopy—Its versatility in analytical chemistry. Anal. Sci. 2012, 28, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudovornik, G.; Korasa, K.; Vrečer, F. A study on the applicability of in-line measurements in the monitoring of the pellet coating process. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 75, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korasa, K.; Hudovornik, G.; Vrečer, F. Applicability of near-infrared spectroscopy in the monitoring of film coating and curing process of the prolonged release coated pellets. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 93, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korasa, K.; Vrečer, F. Overview of PAT process analysers applicable in monitoring of film coating unit operations for manufacturing of solid oral dosage forms. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 111, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, M.; Folestad, S.; Gottfries, J.; Johansson, M.O.; Josefson, M.; Wahlund, K.G. Quantitative analysis of film coating in a fluidized bed process by in-line NIR spectrometry and multivariate batch calibration. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 2099–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ramos, J.D.; Findlay, W.P.; Peck, G.; Morris, K.R. Quantitative analysis of film coating in a pan coater based on in-line sensor measurements. Aaps Pharmscitech 2005, 6, E127–E136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogdill, R.P.; Forcht, R.N.; Shen, Y.; Taday, P.F.; Creekmore, J.R.; Anderson, C.A.; Drennen, J.K. Comparison of terahertz pulse imaging and near-infrared spectroscopy for rapid, non-destructive analysis of tablet coating thickness and uniformity. J. Pharm. Innov. 2007, 2, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabasi, S.H.; Fahmy, R.; Bensley, D.; O’Brien, C.; Hoag, S.W. Quality by design, part II: Application of NIR spectroscopy to monitor the coating process for a pharmaceutical sustained release product. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 4052–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyadi, C.; Karande, A.; Chan, L.; Heng, P. Comparative study of non-destructive methods to quantify thickness of tablet coatings. Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 398, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möltgen, C.V.; Herdling, T.; Reich, G. A novel multivariate approach using science-based calibration for direct coating thickness determination in real-time NIR process monitoring. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 85, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyasu, A.; Hattori, Y.; Otsuka, M. Non-destructive prediction of enteric coating layer thickness and drug dissolution rate by near-infrared spectroscopy and X-ray computed tomography. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 525, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, Y.; Sugata, M.; Kamata, H.; Nagata, M.; Nagato, T.; Hasegawa, K.; Otsuka, M. Real-time monitoring of the tablet-coating process by near-infrared spectroscopy-Effects of coating polymer concentrations on pharmaceutical properties of tablets. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 46, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, P.; Peter, A.; Wolfgang, M.; Khinast, J. How to measure coating thickness of tablets: Method comparison of optical coherence tomography, near-infrared spectroscopy and weight-, height-and diameter gain. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 142, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Liu, X.; Luo, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y. Evaluation of coating uniformity for the digestion-aid tablets by portable near-infrared spectroscopy. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 622, 121833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorachinov, F.; Tnokovska, K.; Koviloska, M.; Atanasova, A.; Antovska, P.; Lazova, J.; Geskovski, N. FT-NIR as a technique for objective measurement of film quality parameters. Maced. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 69, 137–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, L.; Leuenberger, H. Terahertz pulsed imaging and near infrared imaging to monitor the coating process of pharmaceutical tablets. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 370, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendre, C.; Genty, M.; Boiret, M.; Julien, M.; Meunier, L.; Lecoq, O.; Baron, M.; Chaminade, P.; Péan, J.M. Development of a process analytical technology (PAT) for in-line monitoring of film thickness and mass of coating materials during a pan coating operation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 43, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hisada, H.; Okayama, A.; Hoshino, T.; Carriere, J.; Koide, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Fukami, T. Determining the distribution of active pharmaceutical ingredients in combination tablets using near IR and low-frequency Raman spectroscopy imaging. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishii, T.; Matsuzaki, K.; Morita, S. Real-time determination and visualization of two independent quantities during a manufacturing process of pharmaceutical tablets by near-infrared hyperspectral imaging combined with multivariate analysis. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 590, 119871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igne, B.; Arai, H.; Drennen, J.K.; Anderson, C.A. Effect of sampling frequency for real-time tablet coating monitoring using near infrared spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2016, 70, 1476–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Woo, Y.A. Optimization of in-line near-infrared measurement for practical real time monitoring of coating weight gain using design of experiments. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2021, 47, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Jiang, L.; Zhong, Y.; Jin, Z.; Rao, X.; Liu, W.; HE, Y.; Guo, Y.; Luo, X. Near-infrared Spectroscopic Quality Control on Coating Process of Vitamin C Yinqiao Tablets. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae 2024, 11, 184–190. [Google Scholar]

- Strachan, C.J.; Rades, T.; Gordon, K.C.; Rantanen, J. Raman spectroscopy for quantitative analysis of pharmaceutical solids. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007, 59, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, J.; Rehbaum, H.; Kleinebudde, P. Raman spectroscopy as a PAT-Tool for film-coating processes: In-Line Predictions Using one PLS Model for Different Cores. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J.; Pettersson, S.; Taylor, L.S. Infrared imaging of laser-induced heating during Raman spectroscopy of pharmaceutical solids. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2002, 30, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Woo, Y.A. Coating process optimization through in-line monitoring for coating weight gain using Raman spectroscopy and design of experiments. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 154, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Knop, K.; Thies, J.; Uerpmann, C.; Kleinebudde, P. Feasibility of Raman spectroscopy as PAT tool in active coating. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2010, 36, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barimani, S.; Kleinebudde, P. Monitoring of tablet coating processes with colored coatings. Talanta 2018, 178, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisazumi, J.; Kleinebudde, P. In-line monitoring of multi-layered film-coating on pellets using Raman spectroscopy by MCR and PLS analyses. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 114, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Torres, S.; Pérez-Ramos, J.D.; Morris, K.R.; Grant, E.R. Raman spectroscopic measurement of tablet-to-tablet coating variability. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2005, 38, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Torres, S.; Pérez-Ramos, J.D.; Morris, K.R.; Grant, E.R. Raman spectroscopy for tablet coating thickness quantification and coating characterization in the presence of strong fluorescent interference. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006, 41, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, J.F.; Dellibovi, M.; Cunningham, C.R. Raman spectroscopy of coated pharmaceutical tablets and physical models for multivariate calibration to tablet coating thickness. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2007, 43, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, J.; Brock, D.; Knop, K.; Zeitler, J.A.; Kleinebudde, P. Prediction of dissolution time and coating thickness of sustained release formulations using Raman spectroscopy and terahertz pulsed imaging. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 80, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barimani, S.; Kleinebudde, P. Evaluation of in–line Raman data for end-point determination of a coating process: Comparison of Science–Based Calibration, PLS-regression and univariate data analysis. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 119, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirges, M.; Funke, A.; Serno, P.; Knop, K.; Kleinebudde, P. Monitoring of an active coating process for two-layer tablets-model development strategies. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.W.; Kim, J.; Eum, C.; Cho, Y.; Park, C.R.; Woo, Y.A.; Kim, H.M.; Chung, H. Hyperspectral Raman line mapping as an effective tool to monitor the coating thickness of pharmaceutical tablets. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 5810–5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitler, J.A.; Gladden, L.F. In-vitro tomography and non-destructive imaging at depth of pharmaceutical solid dosage forms. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009, 71, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.; Müller, R.; Römer, M.; Gordon, K.; Heinämäki, J.; Kleinebudde, P.; Pepper, M.; Rades, T.; Shen, Y.; Strachan, C.; et al. Analysis of sustained-release tablet film coats using terahertz pulsed imaging. J. Control. Release 2007, 119, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russe, I.S.; Brock, D.; Knop, K.; Kleinebudde, P.; Zeitler, J.A. Validation of terahertz coating thickness measurements using X-ray microtomography. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 3551–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeitler, J.A.; Shen, Y.; Baker, C.; Taday, P.F.; Pepper, M.; Rades, T. Analysis of coating structures and interfaces in solid oral dosage forms by three dimensional terahertz pulsed imaging. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 96, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, R.K.; Evans, M.J.; Zhong, S.; Warr, I.; Gladden, L.F.; Shen, Y.; Zeitler, J.A. Terahertz in-line sensor for direct coating thickness measurement of individual tablets during film coating in real-time. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, A.J.; Cole, B.E.; Taday, P.F. Nondestructive analysis of tablet coating thicknesses using terahertz pulsed imaging. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.; Cuppok, Y.; Muschert, S.; Gordon, K.C.; Pepper, M.; Shen, Y.; Siepmann, F.; Siepmann, J.; Taday, P.F.; Rades, T. Effects of film coating thickness and drug layer uniformity on in vitro drug release from sustained-release coated pellets: A case study using terahertz pulsed imaging. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 382, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momose, W.; Yoshino, H.; Katakawa, Y.; Yamashita, K.; Imai, K.; Sako, K.; Kato, E.; Irisawa, A.; Yonemochi, E.; Terada, K. Applying terahertz technology for nondestructive detection of crack initiation in a film-coated layer on a swelling tablet. Results Pharma Sci. 2012, 2, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.; Müller, R.; Gordon, K.C.; Kleinebudde, P.; Pepper, M.; Rades, T.; Shen, Y.; Taday, P.F.; Zeitler, J.A. Terahertz pulsed imaging as an analytical tool for sustained-release tablet film coating. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009, 71, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haaser, M.; Naelapää, K.; Gordon, K.C.; Pepper, M.; Rantanen, J.; Strachan, C.J.; Taday, P.F.; Zeitler, J.A.; Rades, T. Evaluating the effect of coating equipment on tablet film quality using terahertz pulsed imaging. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 85, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, M.; Hiraishi, Y. Quantitative analysis of visible surface defect risk in tablets during film coating using terahertz pulsed imaging. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 461, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, M.; Hiraishi, Y.; Terada, K. Evaluation of coating properties of enteric-coated tablets using terahertz pulsed imaging. Pharm. Res. 2014, 31, 2140–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Williams, B.M.; May, R.K.; Evans, M.J.; Zhong, S.; Gladden, L.F.; Shen, Y.; Zeitler, J.A.; Lin, H. Optimizing terahertz waveform selection of a pharmaceutical film coating process using recurrent network. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Zeitler, J.A. Visualising liquid transport through coated pharmaceutical tablets using Terahertz pulsed imaging. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 619, 121703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Nassar, M.; Friend, B.; Teckoe, J.; Zeitler, J.A. Studying the dissolution of immediate release film coating using terahertz pulsed imaging. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 630, 122456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Muñoz, S.; Gierer, D.S. Coating uniformity assessment for colored immediate release tablets using multivariate image analysis. Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 395, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschberg, C.; Edinger, M.; Holmfred, E.; Rantanen, J.; Boetker, J. Image-based artificial intelligence methods for product control of tablet coating quality. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehle, A.; Likar, B.; Tomaževič, D. In-line recognition of agglomerated pharmaceutical pellets with density-based clustering and convolutional neural network. Ipsj Trans. Comput. Vis. Appl. 2017, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavurala, N.; Xu, X.; Krishnaiah, Y.S. Hyperspectral imaging using near infrared spectroscopy to monitor coat thickness uniformity in the manufacture of a transdermal drug delivery system. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 523, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravn, C.; Skibsted, E.; Bro, R. Near-infrared chemical imaging (NIR-CI) on pharmaceutical solid dosage forms—Comparing common calibration approaches. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2008, 48, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, J.; Blanco, M. Content uniformity studies in tablets by NIR-CI. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2011, 56, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, L.M.; Park, E.; Tewari, J.; Cho, B.K. Spectroscopic techniques for nondestructive quality inspection of pharmaceutical products: A review. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 40, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, K.; Ishikawa, D.; Genkawa, T.; Ozaki, Y. An application for the quantitative analysis of pharmaceutical tablets using a rapid switching system between a near-infrared spectrometer and a portable near-infrared imaging system equipped with fiber optics. Appl. Spectrosc. 2018, 72, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palou, A.; Cruz, J.; Blanco, M.; Tomàs, J.; De Los Ríos, J.; Alcalà, M. Determination of drug, excipients and coating distribution in pharmaceutical tablets using NIR-CI. J. Pharm. Anal. 2012, 2, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, L.M.; Tewari, J.; Gopinathan, N.; Boulas, P.; Cho, B.K. In-process control assay of pharmaceutical microtablets using hyperspectral imaging coupled with multivariate analysis. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 11055–11061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.P.; Duchesne, C.; Poulin, É.; Lapointe-Garant, P.P. In-line cosmetic end-point detection of batch coating processes for colored tablets using multivariate image analysis. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 606, 120953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.M.; Hannesschläger, G.; Leitner, M.; Khinast, J. Non-destructive analysis of tablet coatings with optical coherence tomography. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 44, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markl, D.; Hannesschläger, G.; Sacher, S.; Leitner, M.; Khinast, J.G. Optical coherence tomography as a novel tool for in-line monitoring of a pharmaceutical film-coating process. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 55, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Shen, Y.C.; Ho, L.; May, R.K.; Zeitler, J.A.; Evans, M.; Taday, P.F.; Pepper, M.; Rades, T.; Gordon, K.C.; et al. Non-destructive quantification of pharmaceutical tablet coatings using terahertz pulsed imaging and optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2011, 49, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; May, R.K.; Evans, M.J.; Zhong, S.; Gladden, L.F.; Shen, Y.; Zeitler, J.A. Impact of processing conditions on inter-tablet coating thickness variations measured by terahertz in-line sensing. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 2513–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Dong, Y.; Markl, D.; Williams, B.M.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zeitler, J.A. Measurement of the intertablet coating uniformity of a pharmaceutical pan coating process with combined terahertz and optical coherence tomography in-line sensing. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Dong, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zeitler, J.A. Quantifying pharmaceutical film coating with optical coherence tomography and terahertz pulsed imaging: An evaluation. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 3377–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y. Development of Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography for Pharmaceutical and Medical Application; The University of Liverpool: Liverpool, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haindl, R.; Kern, A.; Deng, S.; Wolfgang, M.; Stranzinger, S.; Liu, M.; Drexler, W.; Leitgeb, R. Investigation of thin pharmaceutical coatings with ultra-high-resolution optical coherence tomography. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Biomedical Optics, Rahway, NJ, USA, 11 August 2023; Optica Publishing Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; p. 126321R. [Google Scholar]

| Tablet Core Properties | Spraying System Parameters | Inlet Air Conditions | Pan Coater Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Tablet size (diameter, thickness). Batch size. Density and moisture content of the tablet. |

Spray rate. Temperature of the spray solution. |

Temperature. Mass flow rate. Airflow rate. |

Diameter. Length. Rotational speed. Baffle geometry. Residence time of tablets in the spray zone. |

| References | Model Assumptions | Model Output | Model Application | Development & Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| am Ende et al. [54] | Tablet temperature is assumed to be the same as the exhaust air temperature. | Exhaust air temperature & humidity. | Both aqueous and organic film coating. Bi-conical coaters such as Vector LDCS-20, etc. | Early model integrating experimentally obtained into the model. |

| Page et al. [56] | Tablet bed divided into spray and dry zones. | Exhaust air and tablet bed temperatures and humidities. | Only aqueous film coating. Cylindrical coaters such as Bohle Lab-Coater. | First model to incorporate zonal division in the bed but does not account for heat loss to the environment. |

| Strong [35] | Evaporative mass transfer occurs at wet-bulb temperature. | Environmental equivalency () & tablet drying rate. | Steady-state operation of the coater. Theoretical (no experimental results) | First attempt to build a theoretical framework to analyze drying efficiency thermodynamically. |

| Prpich et al. [66] | Same as am Ende et al. 2005 [54]. | Same as am Ende et al. 2005 [54]. | Only aqueous film coating. Bi-conical coaters such as Glatt GC 1250, etc. | Adaptation of am Ende & Berchielli (2005) [54] model to different coater types. |

| Rodrigues et al. [55] | Uses lumped parameters in heat and mass transfer. | Exhaust air and tablet bed temperatures and humidities. | Only aqueous film coating. Bi-conical coaters such as Accela-Cota coater. | Builds on Page et al. (2006a,b) [56] by incorporating heat loss and lumped parameter modeling while excluding zoning complexity and tablet exchange rate estimation. |

| Technique | Information | Strengths/Advantages | Limitations/Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Modeling | Simulates coating process through coupled mass and energy balances between air, spray, and tablet bed. | •

Facilitates virtual testing, reducing costly and time-consuming trial-and-error experiments. • Applicable across scales (lab to production), supporting process design and scale-up. • Enables optimization of critical variables (inlet air temperature, spray rate, pan speed). |

• Limited representation of particle-scale dynamics (mixing, residence time distribution). • Spray-related factors (nozzle number, angles, spray zone coverage, pattern air) not included [54]. • Challenges in modeling droplet size and wetting behavior, accurate modeling of droplet size and wetting requires specialized measurements [34]. • Cannot capture real-time process variability (e.g., nozzle clogging, air fluctuations). • Simplified assumptions for heat and mass transfer, ignoring local variations in the bed. • Mechanical defect mechanisms (twinning, orange peel, overwetting) excluded. |

| Discrete Element Modeling () | Simulates tablets movement and mixing using Newton’s equations of motion. |

• Captures detailed particle motion, mixing, and residence time distribution. • Provides insights into intra- and inter-tablet coating variability. • Can model non-spherical particles with glued sphere approach [89]. • Effect of different tablet shapes and drum geometry (e.g baffle shape and number, spray zone coverage) can be investigated by the [27]. |

• Computationally very expensive, especially for industrial-scale coaters [90]. • Requires calibration of input parameters (friction, restitution, cohesion), which are difficult to measure. • Coupling with a postprocessing approach (e.g., , , , ray-tracing) is needed to obtain particle-level information [74]. |

| Population Balance Models () | Considers coating formation as the accumulative result of repetitive random passes through the spray zone. | • Provides information on coating mass distribution among tablets as a function of time (inter-tablet variability). • Effective for examining how changes in process parameters affect qualitative trends [90]. • Computationally efficient compared to . |

• Dependent on experiments or other simulation methods to determine a priori parameters and . • is based on compartmental and exchange models, which might not fully capture the complex 3D dynamics of the tablets, spray dynamics or detailed droplet behavior [90]. • alone is incapable of capturing intra-tablet uniformity. • Predictions outside the calibrated range are unreliable [90]. |

| CQAs | Reference Method | References |

|---|---|---|

| Single point thickness comparison | Optical microscopy Near-infrared spectroscopy | [162] |

| Multipoint comparison Coating uniformity Limit of detection | Optical microscopy Near-infrared spectroscopy | [127] |

| Intra-tablet variation in coating thickness | - | [160] |

| Coating uniformity and morphology | Dissolution test | [163] |

| Coating thickness distribution and defects | NIR chemical imaging | [136] |

| Intra-batch coating thickness distribution * | Off-line terahertz imaging Weight gain | [161] |

| Coating layer density Coating/core interface | - | [164] |

| Coating thickness and density | Dissolution test Weight gain | [165,166] |

| Coating morphology and defects | SEM | [167] |

| Coating thickness and uniformity Coating interface and morphology | X-ray microtomography | [168] |

| Coating thickness * | Off-line terahertz spectroscopy | [169] |

| Coating layer thickness Coating interface and morphology | X-ray microtomography | [170] |

| Dissolution of immediate release film coating | - | [171] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aminahmadi, B.; Vaes, E.; Willemse, F.; Braile, D.; Gomez, L.N.; Andersen, S.K.; Beer, T.D.; Kumar, A. Experimental and Modeling-Based Approaches for Mechanistic Understanding of Pan Coating Process—A Detailed Review. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010019

Aminahmadi B, Vaes E, Willemse F, Braile D, Gomez LN, Andersen SK, Beer TD, Kumar A. Experimental and Modeling-Based Approaches for Mechanistic Understanding of Pan Coating Process—A Detailed Review. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleAminahmadi, Behrad, Elise Vaes, Filip Willemse, Domenica Braile, Luz Naranjo Gomez, Sune Klint Andersen, Thomas De Beer, and Ashish Kumar. 2026. "Experimental and Modeling-Based Approaches for Mechanistic Understanding of Pan Coating Process—A Detailed Review" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010019

APA StyleAminahmadi, B., Vaes, E., Willemse, F., Braile, D., Gomez, L. N., Andersen, S. K., Beer, T. D., & Kumar, A. (2026). Experimental and Modeling-Based Approaches for Mechanistic Understanding of Pan Coating Process—A Detailed Review. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010019