Tailorable Antibacterial Activity and Biofilm Eradication Properties of Biocompatible α-Hydroxy Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs)

2.2. Methods of Investigations

2.2.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

2.2.2. Density and Dynamic Viscosity

2.2.3. Surface Tension

2.2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

2.2.5. pH Measurement

2.2.6. Antibacterial Activity of DESs (Agar Diffusion Test)

2.2.7. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of DESs

2.2.8. Time-Kill Kinetics Assay

2.2.9. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.2.10. Biofilm Inhibition Assay

2.2.11. Biofilm Eradication Assay

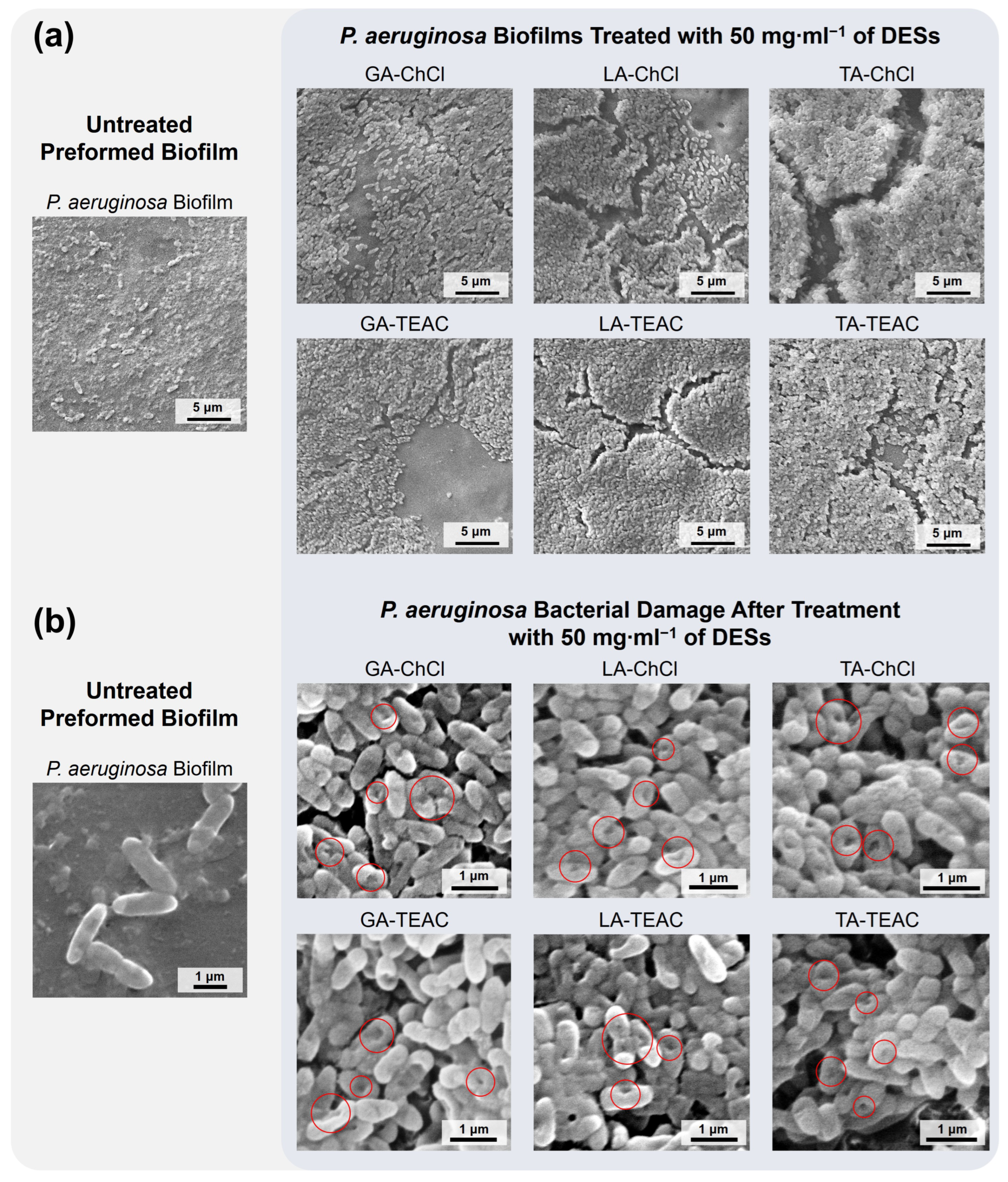

2.2.12. Biofilms Morphology

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

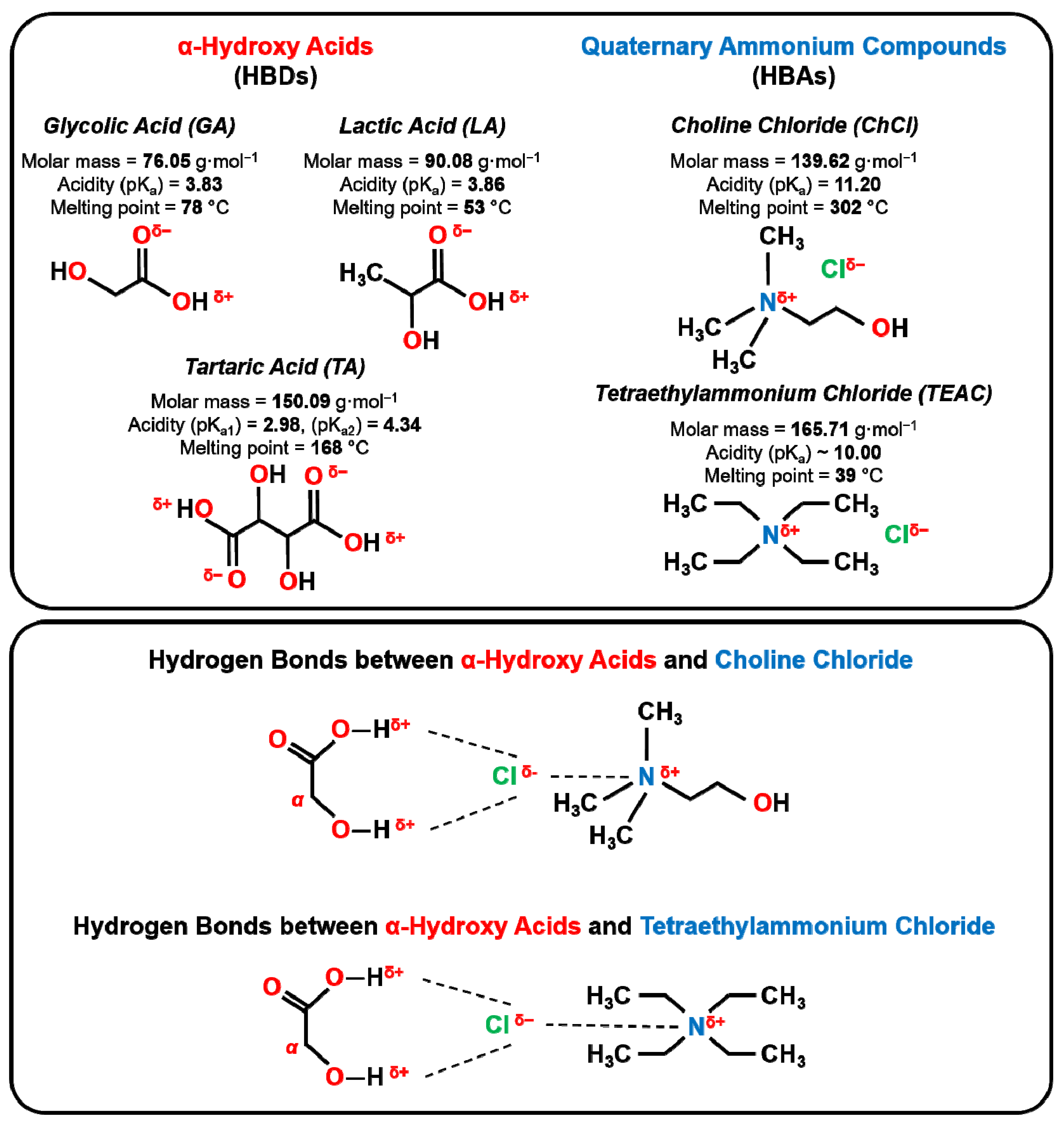

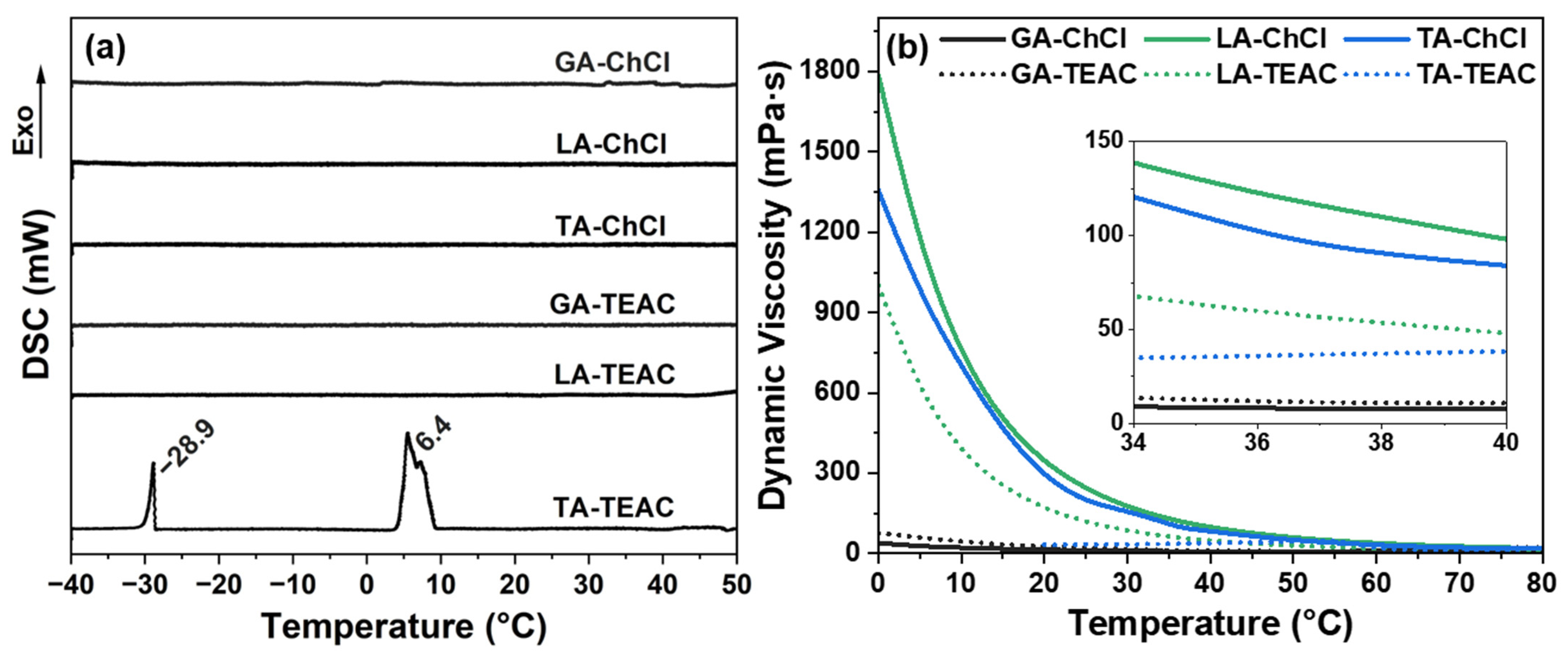

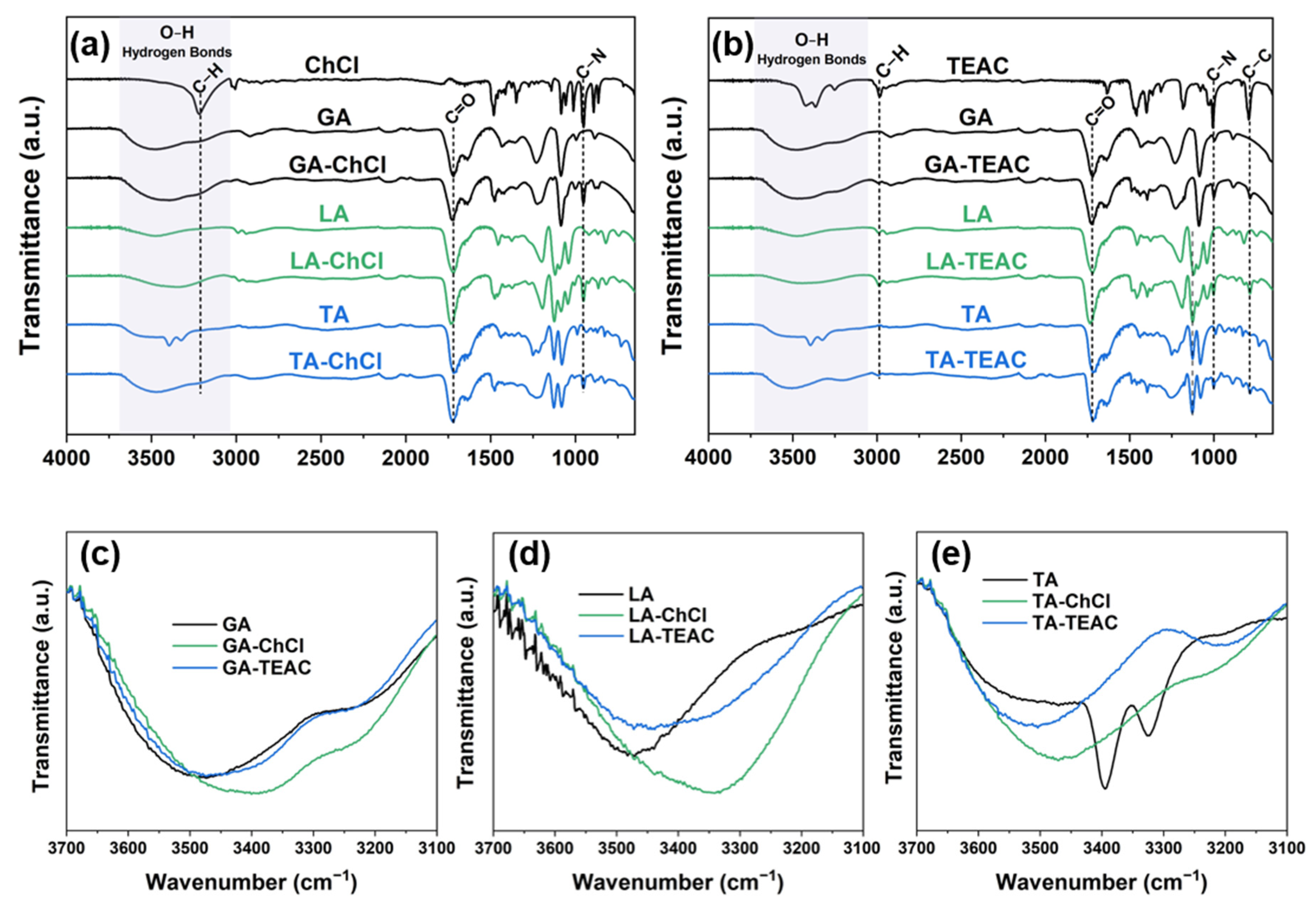

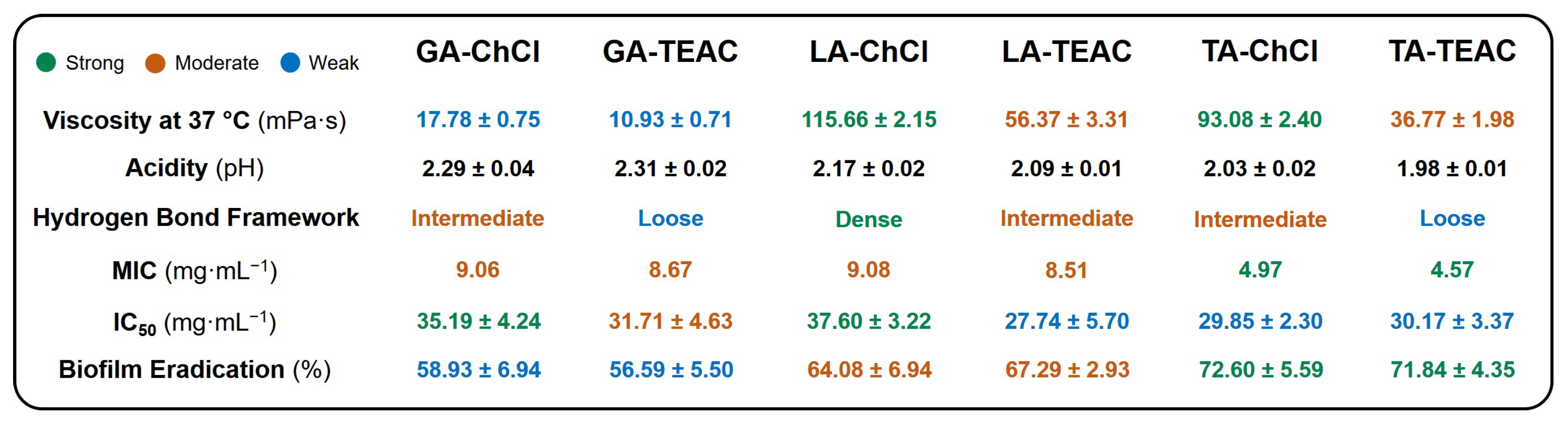

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization

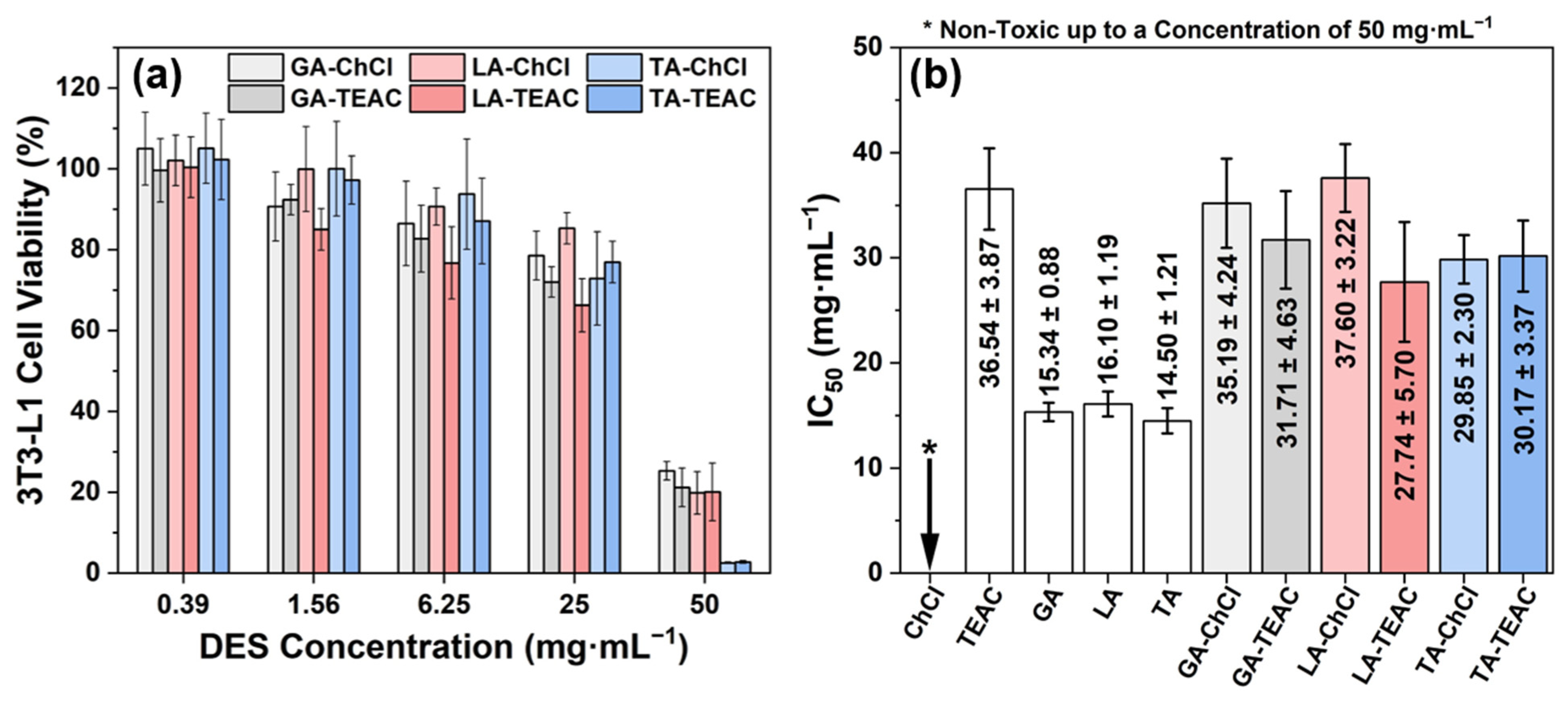

3.2. Biological Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, H.Y.; Prentice, E.L.; Webber, M.A. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Biofilms. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooters, K.E.; Ku, J.C.; Richter, D.M.; Krinock, M.J.; Minor, A.; Li, P.; Kim, A.; Sawyer, R.; Li, Y. Strategies for Combating Antibiotic Resistance in Bacterial Biofilms. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1352273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yin, R.; Cheng, J.; Lin, J. Bacterial Biofilm Formation on Biomaterials and Approaches to Its Treatment and Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Understanding Bacterial Biofilms: From Definition to Treatment Strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1137947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J.M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B.W.; et al. Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Achkar, T.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Fourmentin, S. Basics and Properties of Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3397–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abranches, D.O.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Everything You Wanted to Know about Deep Eutectic Solvents but Were Afraid to Be Told. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2023, 14, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.; Craveiro, R.; Aroso, I.; Martins, M.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents—Solvents for the 21st Century. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amesho, K.T.T.; Lin, Y.-C.; Mohan, S.V.; Halder, S.; Ponnusamy, V.K.; Jhang, S.-R. Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Transformation of Biomass into Biofuels and Fine Chemicals: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 183–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, T.; Hussain, S.; Zhu, M. Deep Eutectic Solvents as an Emerging Green Platform for the Synthesis of Functional Materials. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 3627–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, S.; Shayanfar, A. Deep Eutectic Solvents for Pharmaceutical Formulation and Drug Delivery Applications. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2020, 25, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelquader, M.M.; Li, S.; Andrews, G.P.; Jones, D.S. Therapeutic Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Comprehensive Review of Their Thermodynamics, Microstructure and Drug Delivery Applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2023, 186, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedair, H.M.; Samir, T.M.; Mansour, F.R. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, N.; Khan, N.A.; Ibrahim, T.; Khamis, M.; Khan, A.S.; Alharbi, A.M.; Alfahemi, H.; Siddiqui, R. Antimicrobial Activity of Novel Deep Eutectic Solvents. Sci. Pharm. 2023, 91, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-Y.; Kumar, A.; Shaikh, M.O.; Huang, S.-H.; Chou, Y.-N.; Yang, C.-C.; Hsu, C.-K.; Kuo, L.-C.; Chuang, C.-H. Biocompatible, Antibacterial, and Stable Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Ionic Gel Multimodal Sensors for Healthcare Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 55244–55257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Yu, X.; Cheng, J.; Shang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Hu, L.; et al. Self-Healing, Antibacterial, and 3D-Printable Polymerizable Deep Eutectic Solvents Derived from Tannic Acid. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 7954–7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibsen, K.N.; Ma, H.; Banerjee, A.; Tanner, E.E.L.; Nangia, S.; Mitragotri, S. Mechanism of Antibacterial Activity of Choline-Based Ionic Liquids (CAGE). ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 2370–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swebocki, T.; Kocot, A.M.; Barras, A.; Arellano, H.; Bonnaud, L.; Haddadi, K.; Fameau, A.; Szunerits, S.; Plotka, M.; Boukherroub, R. Comparison of the Antibacterial Activity of Selected Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Deep Eutectic Solvents Comprising Organic Acids (OA-DESs) Toward Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Species. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2303475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swebocki, T.; Barras, A.; Abderrahmani, A.; Haddadi, K.; Boukherroub, R. Deep Eutectic Solvents Comprising Organic Acids and Their Application in (Bio)Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Sarraguça, M. A Comprehensive Review on Deep Eutectic Solvents and Its Use to Extract Bioactive Compounds of Pharmaceutical Interest. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chang, T.; Yang, H.; Cui, M. Antibacterial Mechanism of Lactic Acid on Physiological and Morphological Properties of Salmonella Enteritidis, Escherichia Coli and Listeria Monocytogenes. Food Control 2015, 47, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eswaranandam, S.; Hettiarachchy, N.S.; Johnson, M.G. Antimicrobial Activity of Citric, Lactic, Malic, or Tartaric Acids and Nisin-incorporated Soy Protein Film Against Listeria Monocytogenes, Escherichia Coli O157:H7, and Salmonella Gaminara. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, FMS79–FMS84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.-Y.; Wang, W.; Yan, H.; Qu, H.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Gu, R. The Effect of Different Organic Acids and Their Combination on the Cell Barrier and Biofilm of Escherichia Coli. Foods 2023, 12, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, C. Quaternary Ammonium Compounds and Their Composites in Antimicrobial Applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 11, 2300946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadagouda, M.N.; Vijayasarathy, P.; Sin, A.; Nam, H.; Khan, S.; Parambath, J.B.M.; Mohamed, A.A.; Han, C. Antimicrobial Activity of Quaternary Ammonium Salts: Structure-Activity Relationship. Med. Chem. Res. 2022, 31, 1663–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macário, I.P.E.; Oliveira, H.; Menezes, A.C.; Ventura, S.P.M.; Pereira, J.L.; Gonçalves, A.M.M.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Gonçalves, F.J.M. Cytotoxicity Profiling of Deep Eutectic Solvents to Human Skin Cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3696:1987; Water for Analytical Laboratory Use—Specification and Test Methods. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987.

- Swebocki, T.; Barras, A.; Maria Kocot, A.; Plotka, M.; Boukherroub, R. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) Assays Using Broth Microdilution Method V1. 2023. Available online: https://www.protocols.io/view/minimum-inhibitory-concentration-mic-and-minimum-b-5qpvo3x6dv4o/v1 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Childs, S.K.; Jones, A.-A.D. A Microtiter Peg Lid with Ziggurat Geometry for Medium-Throughput Antibiotic Testing and in Situ Imaging of Biofilms. Biofilm 2023, 6, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yu, D.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Z.; Mu, T. Novel Deep Eutectic Solvents with Different Functional Groups towards Highly Efficient Dissolution of Lignin. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 5291–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, G.A. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Herschlag, D.; Pinney, M.M. Hydrogen Bonds: Simple after All? Biochemistry 2018, 57, 3338–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, M. Hydrogen Bonds. Molecules 2023, 28, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, P. Competing Intramolecular vs. Intermolecular Hydrogen Bonds in Solution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 19562–19633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, Z. Insights into the Hydrogen Bond Interactions in Deep Eutectic Solvents Composed of Choline Chloride and Polyols. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 7760–7767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijardar, S.P.; Singh, V.; Gardas, R.L. Revisiting the Physicochemical Properties and Applications of Deep Eutectic Solvents. Molecules 2022, 27, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruhzit, O.M.; Fisken, R.A.; Cooper, B.J. Tetraethylammonium chloride [(C2H5)4NCl]. Acute and chronic toxicity in experimental animals. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1948, 92, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydın Kurç, M.; Orak, H.H.; Gülen, D.; Caliskan, H.; Argon, M.; Sabudak, T. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Efficacy of the Lipophilic Extract of Cirsium Vulgare. Molecules 2023, 28, 7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.A.; Kaium, M.A.; Uddin, S.N.; Uddin, M.J.; Olawuyi, O.; Campbell, A.D.; Saint-Louis, C.J.; Halim, M.A. Elucidating the Structure, Dynamics, and Interaction of a Choline Chloride and Citric Acid Based Eutectic System by Spectroscopic and Molecular Modeling Investigations. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 38243–38251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, H.G.; Sun, C.C.; Neervannan, S. Characterization of Thermal Behavior of Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Potential as Drug Solubilization Vehicles. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 378, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, M.; van den Bruinhorst, A.; Kroon, M.C. Low-Transition-Temperature Mixtures (LTTMs): A New Generation of Designer Solvents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3074–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanovic, R.; Ludwig, M.; Webber, G.B.; Atkin, R.; Page, A.J. Nanostructure, Hydrogen Bonding and Rheology in Choline Chloride Deep Eutectic Solvents as a Function of the Hydrogen Bond Donor. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 3297–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zuo, Z.; Cao, B.; Wang, H.; Lu, L.; Lu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, X. A Comprehensive Study of Density, Viscosity, and Electrical Conductivity of Choline Halide-Based Eutectic Solvents in H2O. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2024, 69, 4362–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaedi, H.; Ayoub, M.; Sufian, S.; Shariff, A.M.; Lal, B. The Study on Temperature Dependence of Viscosity and Surface Tension of Several Phosphonium-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 241, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Pan, Y.; Gao, D.; Qu, H. Experimental Study on the Transport Properties of 12 Novel Deep Eutectic Solvents. Polymers 2024, 16, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Liu, Y.; Sebbah, T.; Cao, X. A Theoretical Study on Terpene-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent: Relationship between Viscosity and Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions. Glob. Chall. 2021, 5, 2000103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichowska-Kopczyńska, I.; Nowosielski, B.; Warmińska, D. Deep Eutectic Solvents: Properties and Applications in CO2 Separation. Molecules 2023, 28, 5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, S.; Benito, C.; Alcalde, R.; Atilhan, M.; Aparicio, S. Insights on the Water Effect on Deep Eutectic Solvents Properties and Structuring: The Archetypical Case of Choline Chloride + Ethylene Glycol. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 344, 117717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciolini, E.; Pastore, G.; Del Giacco, T.; Ciancaleoni, G.; Tiecco, M.; Germani, R. Aquo-DESs: Water-Based Binary Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 383, 122057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazali, A.L.; AlMasoud, N.; Amran, S.K.; Alomar, T.S.; Pa’ee, K.F.; El-Bahy, Z.M.; Yong, T.-L.K.; Dailin, D.J.; Chuah, L.F. Physicochemical and Thermal Characteristics of Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghbakhsh, R.; Taherzadeh, M.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Raeissi, S. A General Model for the Surface Tensions of Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 307, 112972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaoui, T.; Boublia, A.; Darwish, A.S.; Alam, M.; Park, S.; Jeon, B.-H.; Banat, F.; Benguerba, Y.; AlNashef, I.M. Predicting the Surface Tension of Deep Eutectic Solvents Using Artificial Neural Networks. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 32194–32207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Fu, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, F.; Mu, T. Surface Tension of 50 Deep Eutectic Solvents: Effect of Hydrogen-Bonding Donors, Hydrogen-Bonding Acceptors, Other Solvents, and Temperature. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 12741–12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivelä, H.; Salomäki, M.; Vainikka, P.; Mäkilä, E.; Poletti, F.; Ruggeri, S.; Terzi, F.; Lukkari, J. Effect of Water on a Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvent. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Correa, E.; Bastías-Montes, J.M.; Acuña-Nelson, S.; Muñoz-Fariña, O. Effect of Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents on Polyphenols Extraction from Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) Bean Shells and Antioxidant Activity of Extracts. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macasoi, C.; Meltzer, V.; Stanculescu, I.; Romanitan, C.; Pincu, E. Binary Mixtures of Meloxicam and L-Tartaric Acid for Oral Bioavailability Modulation of Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, M.A.; Malik, T.; Naeem, A.; Khan, A.S.; Ud Din, I.; Shaharun, M.S. Exploring the Dynamic World of Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvents: Synthesis, Characterization, and Key Properties Unveiled. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athokpam, B.; Ramesh, S.G.; McKenzie, R.H. Effect of Hydrogen Bonding on the Infrared Absorption Intensity of OH Stretch Vibrations. Chem. Phys. 2017, 488–489, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panić, M.; Radović, M.; Cvjetko Bubalo, M.; Radošević, K.; Rogošić, M.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Radojčić Redovniković, I.; Jurinjak Tušek, A. Prediction of PH Value of Aqueous Acidic and Basic Deep Eutectic Solvent Using COSMO-RS σ Profiles’ Molecular Descriptors. Molecules 2022, 27, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubonja-Šonje, M.; Knežević, S.; Abram, M. Challenges to Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Plant-Derived Polyphenolic Compounds. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2020, 71, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.L.; Lim, L.Y.; Hammer, K.; Hettiarachchi, D.; Locher, C. A Review of Commonly Used Methodologies for Assessing the Antibacterial Activity of Honey and Honey Products. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Obluchinskaya, E.D.; Shikova, V.A.; Flisyuk, E.V.; Vishnyakov, E.V.; Makarevich, E.V.; Shikov, A.N. Physicochemical and Antimicrobial Properties of Lactic Acid-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as a Function of Water Content. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynaud, S.; Danzi, D.; Vandelle, E.; Gardrat, C.; Coloma, F.; Morris, C.; Coma, V. Chitosan and Carboxylic Acids, Impact on Membrane Permeability and DNA Integrity of Pseudomonas Syringae: Interest for Biocontrol Applications. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, N.P.; Marshall, R.; Pinheiro, M.J.F.; Dieckmann, R.; Dahouk, S.A.; Skroza, N.; Rudnicka, K.; Lund, P.A.; De Biase, D. On the Potential Role of Naturally Occurring Carboxylic Organic Acids as Anti-Infective Agents: Opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 140, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.; Mandal, A.; Dhawan, S.; Shevachman, M.; Mitragotri, S.; Joshi, N. Clinical Translation of Choline and Geranic Acid Deep Eutectic Solvent. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2021, 6, e10191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, B.M.; Gligorijević, N.; Aranđelović, S.; Macedo, A.C.; Jurić, T.; Uka, D.; Mocko-Blažek, K.; Serra, A.T. Cytotoxicity Profiling of Choline Chloride-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 3520–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenkranz, H.S.; Matthews, E.J.; Klopman, G. Relationships between Cellular Toxicity, the Maximum Tolerated Dose, Lipophilicity and Electrophilicity. Altern. Lab. Anim. 1992, 20, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arechabala, B.; Coiffard, C.; Rivalland, P.; Coiffard, L.J.M.; Roeck-Holtzhauer, Y. De Comparison of Cytotoxicity of Various Surfactants Tested on Normal Human Fibroblast Cultures Using the Neutral Red Test, MTT Assay and LDH Release. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1999, 19, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinenko, G.E.; Myshova, A.E.; Igumnova, O.A.; Golovina, K.S.; Plotnikov, E.V.; Badaraev, A.D.; Rutkowski, S.; Filimonov, V.D.; Tverdokhlebov, S.I. Bacterial Inhibition and Biofilm Eradication Ability of Low-Toxic Deep Eutectic Solvents Prepared from Lactic Acid and Quaternary Ammonium Compounds. Mater. Lett. 2025, 378, 137591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Data from the EUCAST MIC Distribution Website. Available online: https://mic.eucast.org/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Lomba, L.; Ribate, M.P.; Sangüesa, E.; Concha, J.; Garralaga, M. P.; Errazquin, D.; García, C.B.; Giner, B. Deep Eutectic Solvents: Are They Safe? Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanot, M.; Lohou, E.; Sonnet, P. Anti-Biofilm Agents to Overcome Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Antibiotic Resistance. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystedt, H.L.; Grønlien, K.G.; Rolfsnes, R.R.; Winther-Larsen, H.C.; Løchen Økstad, O.A.; Tønnesen, H.H. Neutral Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as Anti-Biofilm Agents. Biofilm 2023, 5, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava-Ocampo, M.F.; Fuhaid, L.A.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; Witkamp, G.J.; Farinha, A.S.F.; Bucs, S.S. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as Biofilm Structural Breakers. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocot, A.M.; Swebocki, T.; Ciemińska, K.; Łupkowska, A.; Kapusta, M.; Grimon, D.; Laskowska, E.; Kaczorowska, A.-K.; Kaczorowski, T.; Boukherroub, R.; et al. Deep Eutectic Solvent Enhances Antibacterial Activity of a Modular Lytic Enzyme against Acinetobacter Baumannii. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-W.; Hou, B.; Liu, G.-Y.; Jiang, H.; Sun, B.; Wang, Z.-N.; Shi, R.-F.; Xu, Y.; Wang, R.; Jia, A.-Q. Attenuation of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm by Hordenine: A Combinatorial Study with Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 9745–9758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banar, M.; Emaneini, M.; Beigverdi, R.; Fanaei Pirlar, R.; Node Farahani, N.; van Leeuwen, W.B.; Jabalameli, F. The Efficacy of Lyticase and β-Glucosidase Enzymes on Biofilm Degradation of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains with Different Gene Profiles. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.C.; Pritchard, M.F.; Ferguson, E.L.; Powell, K.A.; Patel, S.U.; Rye, P.D.; Sakellakou, S.-M.; Buurma, N.J.; Brilliant, C.D.; Copping, J.M.; et al. Targeted Disruption of the Extracellular Polymeric Network of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms by Alginate Oligosaccharides. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2018, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, A.K.; Panlilio, H.; Pusavat, J.; Wouters, C.L.; Moen, E.L.; Rice, C.V. Overcoming Multidrug Resistance and Biofilms of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa with a Single Dual-Function Potentiator of β-Lactams. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.M.; Soares, F.A.; Reis, S.; Nunes, C.; Van Dijck, P. Innovative Strategies Toward the Disassembly of the EPS Matrix in Bacterial Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Song, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, J.; Wang, X.; Malakar, P.K.; Liu, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y. Removal of Foodborne Pathogen Biofilms by Acidic Electrolyzed Water. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DES | HBD | HBA | nHBD (mol) | nHBA (mol) | Water (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-ChCl | Glycolic Acid | Choline Chloride | 2 | 1 | 18.3 |

| GA-TEAC | Glycolic Acid | Tetraethylammonium Chloride | 17.0 | ||

| LA-ChCl | L-(+)-Lactic Acid | Choline Chloride | 9.2 | ||

| LA-TEAC | L-(+)-Lactic Acid | Tetraethylammonium Chloride | 8.6 | ||

| TA-ChCl | L-(+)-Tartaric Acid | Choline Chloride | 14.6 | ||

| TA-TEAC | L-(+)-Tartaric Acid | Tetraethylammonium Chloride | 13.9 |

| DES Formation | Dynamic Viscosity * (mPa·s) | Density * (g·cm−3) | Surface Tension * (mN·m−1) | pH † | Tcc (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-ChCl | 17.78 ± 0.75 | 1.16 ± 0.01 | 56.43 ± 0.11 | 2.29 ± 0.04 | - |

| GA-TEAC | 10.93 ± 0.71 | 1.10 ± 0.02 | 59.05 ± 0.08 | 2.31 ± 0.02 | - |

| LA-ChCl | 115.66 ± 2.15 | 1.16 ± 0.02 | 43.33 ± 0.01 | 2.17 ± 0.02 | - |

| LA-TEAC | 56.37 ± 3.31 | 1.09 ± 0.02 | 45.81 ± 0.04 | 2.09 ± 0.01 | - |

| TA-ChCl | 93.08 ± 2.40 | 1.26 ± 0.01 | 45.62 ± 0.23 | 2.03 ± 0.02 | - |

| TA-TEAC | 36.77 ± 1.98 | 1.17 ± 0.03 | 54.22 ± 0.10 | 1.98 ± 0.01 | 6.32 ± 1.22 |

| DES | Zone of Inhibition (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | MRSA | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | |

| Antibiotic * | 32–36 | 15–17 | 13–14 | 14–16 |

| GA-ChCl | 19–21 | 19–20 | 18–20 | 17–18 |

| GA-TEAC | 16–19 | 19–20 | 17–18 | 17–18 |

| LA-ChCl | 21–22 | 18–19 | 19–20 | 20–21 |

| LA-TEAC | 15–16 | 17–18 | 14–16 | 15–16 |

| TA-ChCl | 16–19 | 17–18 | 16–18 | 16–18 |

| TA-TEAC | 20–21 | 19–20 | 19–20 | 20–21 |

| Antibacterial Properties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DES Formulation | MIC MBC (mg·mL−1) | Bacterial Strain | |||

| Gram-Positive | Gram-Negative | ||||

| S. aureus | MRSA | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | ||

| Antibiotic † [70] | MIC | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| GA | MIC MBC | 4.97 19.85 | 4.97 19.85 | 4.97 19.85 | 4.97 19.85 |

| LA | MIC MBC | 2.80 44.20 | 2.80 88.30 | 5.50 44.20 | 2.80 44.20 |

| TA | MIC MBC | 3.91 15.63 | 3.91 15.63 | 3.91 15.63 | 3.91 15.63 |

| ChCl | MIC MBC | - * - | - - | - - | - - |

| TEAC | MIC MBC | - - | - - | - - | - - |

| GA-ChCl | MIC MBC | 9.06 36.25 | 9.06 36.25 | 9.06 18.13 | 9.06 18.13 |

| GA-TEAC | MIC MBC | 8.67 17.35 | 8.67 17.35 | 8.67 34.69 | 8.67 34.69 |

| LA-ChCl | MIC MBC | 9.08 34.40 | 9.08 34.40 | 9.08 34.40 | 9.08 34.4 |

| LA-TEAC | MIC MBC | 8.51 29.00 | 8.51 29.00 | 8.51 29.00 | 8.51 29.00 |

| TA-ChCl | MIC MBC | 4.97 9.92 | 4.97 9.92 | 4.97 9.92 | 4.97 9.92 |

| TA-TEAC | MIC MBC | 4.57 9.14 | 4.57 9.14 | 4.57 18.23 | 4.57 18.23 |

| DES Formulation | Time to Eradicate 99.9% of Bacteria (h) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strain | ||||

| Gram-Positive | Gram-Negative | |||

| S. aureus | MRSA | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | |

| GA-ChCl | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| GA-TEAC | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| LA-ChCl | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| LA-TEAC | 6 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| TA-ChCl | 6 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| TA-TEAC | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dubinenko, G.; Senkina, E.; Golovina, K.; Myshova, A.; Igumnova, O.; Plotnikov, E.; Badaraev, A.; Rutkowski, S.; Filimonov, V.; Tverdokhlebov, S. Tailorable Antibacterial Activity and Biofilm Eradication Properties of Biocompatible α-Hydroxy Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010016

Dubinenko G, Senkina E, Golovina K, Myshova A, Igumnova O, Plotnikov E, Badaraev A, Rutkowski S, Filimonov V, Tverdokhlebov S. Tailorable Antibacterial Activity and Biofilm Eradication Properties of Biocompatible α-Hydroxy Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleDubinenko, Gleb, Elena Senkina, Ksenia Golovina, Alexandra Myshova, Olga Igumnova, Evgenii Plotnikov, Arsalan Badaraev, Sven Rutkowski, Victor Filimonov, and Sergei Tverdokhlebov. 2026. "Tailorable Antibacterial Activity and Biofilm Eradication Properties of Biocompatible α-Hydroxy Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010016

APA StyleDubinenko, G., Senkina, E., Golovina, K., Myshova, A., Igumnova, O., Plotnikov, E., Badaraev, A., Rutkowski, S., Filimonov, V., & Tverdokhlebov, S. (2026). Tailorable Antibacterial Activity and Biofilm Eradication Properties of Biocompatible α-Hydroxy Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010016