Clinical Characteristics, Long-Term Pharmacokinetics, and Outcomes in Kidney Transplant Recipients from an African Tertiary Centre: A 10-Year Single-Centre Retrospective Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

2.2. Outcome Definitions

2.3. Synopsis of Transplant Care Protocol

2.3.1. Risk Stratification and Immunosuppressive Agents

2.3.2. Infection Prophylaxis

2.3.3. Calcineurin Inhibitors CNI Level Measurement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Graft and Patient Survival Analysis

3.3. Graft Loss Profile

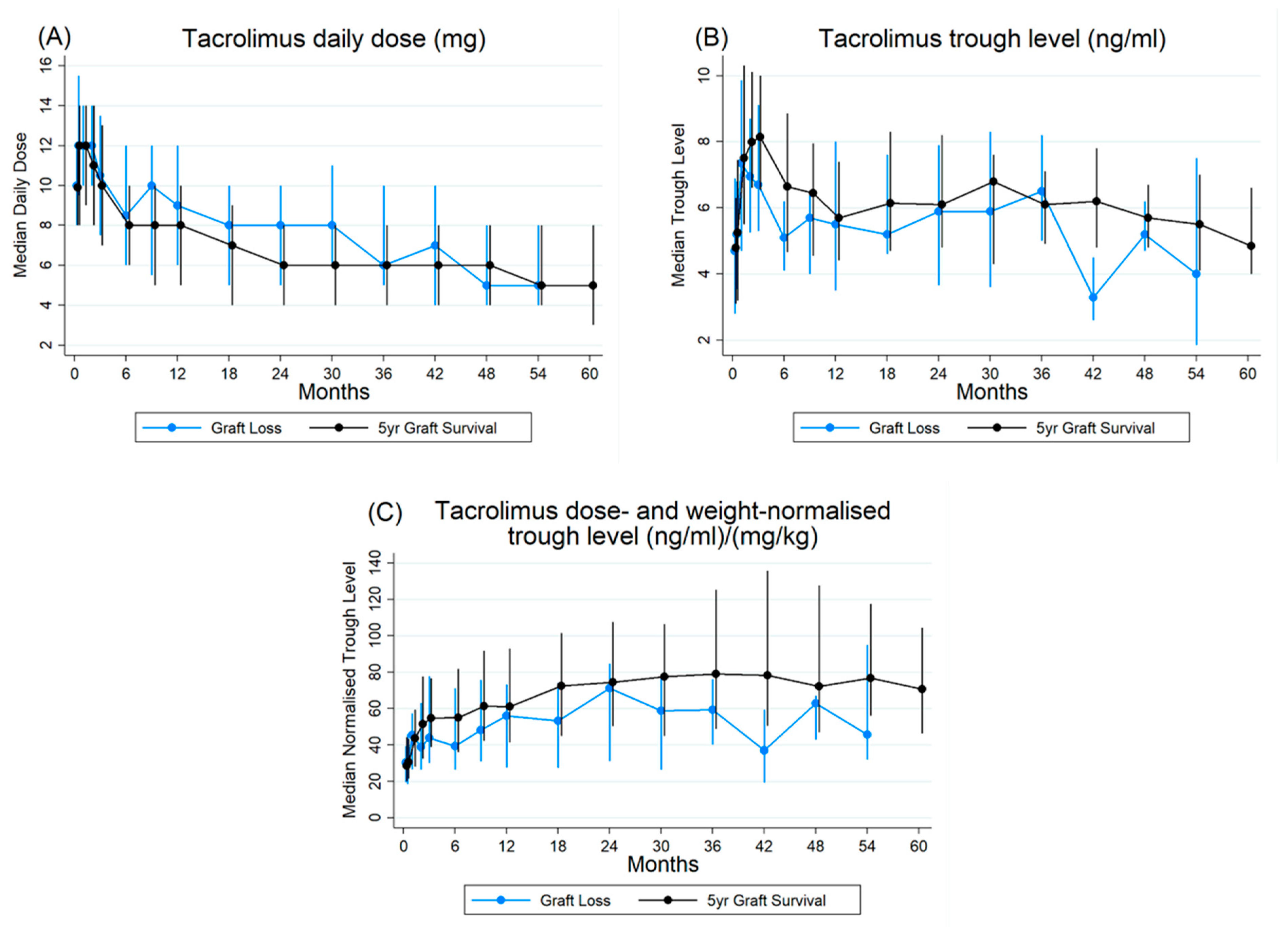

3.4. Pharmacokinetic Profile of Tacrolimus

3.5. Pharmacokinetics and Graft Survival

4. Discussion

4.1. Graft Survival

4.2. Dose, Trough, and Normalised Trough Trends

4.3. Patient Survival

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tonelli, M.; Wiebe, N.; Knoll, G.; Bello, A.; Browne, S.; Jadhav, D.; Klarenbach, S.; Gill, J. Systematic review: Kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am. J. Transplant. 2011, 11, 2093–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyld, M.; Morton, R.L.; Hayen, A.; Howard, K.; Webster, A.C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of utility-based quality of life in chronic kidney disease treatments. PLoS Med. 2012, e1001307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyesubula, R.; Aklilu, A.M.; Calice-Silva, V.; Kumar, V.; Kansiime, G. The Future of Kidney Care in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Challenges, Triumphs and Opportunities. Kidney360 2024, 5, 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.E.; Kaur, A.; Jewitt-Harris, J.; Ready, A.; Milford, D.V. Kidney transplantation in low-and middle-income countries: The Transplant Links experience. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2024, 39, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, J.; Maher, H.; Bentley, A.; Crymble, K.; Rossi, B.; Aucamp, L.; Gottlich, E.; Loveland, J.; Botha, J.; Botha, J. Favourable outcomes for the first 10 years of kidney and pancreas transplantation at Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016, 106, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loveland, J.; Britz, R.; Joseph, C.; Sparaco, A.; Zuckerman, M.; Langnas, A.; Schleicher, G.; Strobele, B.; Moshesh, P.; Botha, J. Paediatric liver transplantation in Johannesburg revisited: 59 transplants and challenges met. S. Afr. Med. J. 2014, 104, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boosi, R.; Dayal, C.; Chiba, S.; Khan, F.; Davies, M. Effect of dialysis modality on kidney transplant outcomes in South Africa: A single-centre experience. Afr. J. Nephrol. 2025, 28, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, B.; Du Toit, T.; Jones, E.S.; Barday, Z.; Manning, K.; Mc Curdie, F.; Thomson, D.; Rayner, B.L.; Muller, E.; Wearne, N. Outcomes and challenges of a kidney transplant programme at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town: A South African perspective. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawinski, D.; Poggio, E.D. Introduction to kidney transplantation: Long-term management challenges. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 1262–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotti, G.; Cremaschi, E.; Maggiore, U. Once-daily prolonged-release tacrolimus formulations for kidney transplantation: What the nephrologist needs to know. J. Nephrol. 2017, 30, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuker, N.; Shuker, L.; van Rosmalen, J.; Roodnat, J.I.; Borra, L.C.; Weimar, W.; Hesselink, D.A.; van Gelder, T. A high intrapatient variability in tacrolimus exposure is associated with poor long-term outcome of kidney transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2016, 29, 1158–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberbauer, R.; Bestard, O.; Furian, L.; Maggiore, U.; Pascual, J.; Rostaing, L.; Budde, K. Optimization of tacrolimus in kidney transplantation: New pharmacokinetic perspectives. Transplant. Rev. 2020, 34, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, H.V.; Hardinger, K.L. Current state of renal transplant immunosuppression: Present and future. World J. Transplant. 2012, 2, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meremo, A.; Paget, G.; Duarte, R.; Dickens, C.; Dix-Peek, T.; Bintabara, D.; Naicker, S. Demographic and clinical profile of black patients with chronic kidney disease attending a tertiary hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T.; Booysen, F.; Mbonigaba, J. Socio-economic inequalities in the multiple dimensions of access to healthcare: The case of South Africa. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nqebelele, N.U.; Dickens, C.; Dix-Peek, T.; Duarte, R.; Naicker, S. JC virus and APOL1 risk alleles in black South Africans with hypertension-attributed CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2019, 4, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeem, A.R.; Asthana, S.; Johnson, R.; Brown, C.; Ahmad, N. Impact of Asian and Black Donor and Recipient Ethnicity on the Outcomes After Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation in the United Kingdom. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 12605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Kim, J.; Jeon, H.; Kim, Y.N.; Shin, H.S.; Rim, H. P1706THE GRAFT SURVIVAL OF KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION ACCORDING TO ETHNICITY IN KIDNEY TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, gfaa142-P1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekbolsynov, D.; Mierzejewska, B.; Khuder, S.; Ekwenna, O.; Rees, M.; Green, R.C.; Stepkowski, S.M. Improving Access to HLA-Matched Kidney Transplants for African American Patients. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 832488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghavi, K.; Brundage, R.C.; Miller, M.B.; Schladt, D.P.; Israni, A.K.; Guan, W.; Oetting, W.S.; Mannon, R.B.; Remmel, R.P.; Matas, A.J.; et al. Genotype-guided tacrolimus dosing in African-American kidney transplant recipients. Pharmacogenomics J. 2017, 17, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, M.; Pankewycz, O.; El-Ghoroury, M.; Shihab, F.; Wiland, A.; McCague, K.; Chan, L. Outcomes in African American kidney transplant patients receiving tacrolimus and mycophenolic acid immunosuppression. Transplantation 2013, 95, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namba-Hamano, T.; Hamano, T.; Doi, Y.; Hiraoka, A.; Yonishi, H.; Sakai, S.; Takahashi, A.; Mizui, M.; Nakazawa, S.; Yamanaka, K.; et al. Clinical Impacts of Allograft Biopsy in Renal Transplant Recipients 10 Years or Longer After Transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kriesche, H.U.; Schold, J.D.; Srinivas, T.R.; Kaplan, B. Lack of improvement in renal allograft survival despite a marked decrease in acute rejection rates over the most recent era. Am. J. Transplant. 2004, 4, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passey, C.; Birnbaum, A.K.; Brundage, R.C.; Oetting, W.S.; Israni, A.K.; Jacobson, P.A. Dosing equation for tacrolimus using genetic variants and clinical factors. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 72, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undre, N.; Schafer, A.; European Tacrolimus Multicentre Renal Study Group. Factors affecting the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in the first year after renal transplantation. In Transplantation Proceedings; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 1261–1263. [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge, H.; Vanhove, T.; de Loor, H.; Verbeke, K.; Kuypers, D.R. Progressive decline in tacrolimus clearance after renal transplantation is partially explained by decreasing CYP3A4 activity and increasing haematocrit. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 80, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiff, J.; Cole, E.; Cantarovich, M. Therapeutic monitoring of calcineurin inhibitors for the nephrologist. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiske, B.L.; Zeier, M.G.; Chapman, J.R.; Craig, J.C.; Ekberg, H.; Garvey, C.A.; Green, M.D.; Jha, V.; Josephson, M.A.; Kiberd, B.A. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients: A summary. Kidney Int. 2010, 77, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, M.; Van Gelder, T.; Åsberg, A.; Haufroid, V.; Hesselink, D.A.; Langman, L.; Lemaitre, F.; Marquet, P.; Seger, C.; Shipkova, M. Therapeutic drug monitoring of tacrolimus-personalized therapy: Second consensus report. Ther. Drug Monit. 2019, 41, 261–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte-Nutgen, K.; Tholking, G.; Suwelack, B.; Reuter, S. Tacrolimus-pharmacokinetic considerations for clinicians. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 342–350. [Google Scholar]

- Cueto-Manzano, A.M.; Rojas, E.; Rosales, G.; Gómez, B.; Martínez, H.R.; Cortés-Sanabria, L.; Flores, A.; Chávez, S.; Camarena, J.L.; González, F. Risk factors for long-term graft loss in kidney transplantation: Experience of a Mexican single-center. Rev. Investig. Clin. Organo Hosp. Enfermedades Nutr. 2002, 54, 492–496. [Google Scholar]

| Overall | 5-Year Graft Survival | Graft Loss | p-Value + | Number of Missing Records | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 194 | n = 121 | n = 68 | 5 ! | ||

| Age at transplant (Median, IQR) | 41.5 (34.0–49.0) | 40.0 (34.0–49.0) | 45.5 (37.5–51.0) | 0.029 $,* | |

| Males (%) | 122 (65.1%) | 73 (60.3%) | 49 (72.1%) | 0.106 | |

| First Kidney transplant (%) | 165 (95.9%) | 100 (95.2%) | 65 (97.0%) | 1.000 # | 22 |

| Cadaveric Donor (%) | 171 (88.1%) | 105 (86.8%) | 62 (91.2%) | 0.365 | |

| Ethnicity (%) | - | - | 8 | ||

| Black | 158 (85.0%) | 100 (82.6%) | 55 (90.2%) | 0.466 # | |

| White | 13 (7%) | 8 (6.6%) | 4 (6.6%) | ||

| Asian | 6 (3.2%) | 5 (4.1%) | 1 (1.6%) | ||

| Mixed | 9 (4.8%) | 8 (6.6%) | 1 (1.6%) | ||

| Antibody induction (%) | 19 | ||||

| Antithymocyte globulin (ATG) | 91 (52.0%) | 50 (47.6%) | 40 (60.6%) | 0.148 # | |

| Basiliximab | 81 (46.3%) | 52 (49.5%) | 26 (39.4%) | ||

| Other | 3 (1.7%) | 3 (2.9%) | 0 | ||

| Co-medication (%) Yes | 120 (64.9%) | 77 (64.7%) | 42 (67.7%) | 0.683 | 9 |

| Calcineurin type (%) | 4 | ||||

| Cyclosporine | 5 (2.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (3.1%) | 0.548 # | |

| Tacrolimus | 146 (76.8%) | 94 (77.7%) | 49 (76.6%) | ||

| Both (Switch) | 39 (20.5%) | 26 (21.5%) | 13 (20.3%) | ||

| Adjunct immunosuppressant ££ | 0.003 * | ||||

| MMF | 164 (84.5%) | 106 (87.6%) | 53 (77.9%) | ||

| MMF/AZT | 21 (10.8%) | 14 (11.6%) | 7 (10.3%) | ||

| Neither MMF/AZT | 9 (4.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 8 (11.8%) | ||

| Delayed Graft Function (%) | 54 (28.7%) | 29 (25.0%) | 25 (37.3%) | 0.078 | 6 |

| Pre-Transplant Hypertension (%) | 160 (94.7%) | 104 (93.7%) | 52 (98.1%) | 0.219 | 25 |

| Post-Transplant Hypertension (%) | 163 (91.1%) | 109 (93.2%) | 52 (91.2%) | 0.649 | 15 |

| Pre-Transplant Diabetes (%) | 4 (2.2%) | 0 | 3 (5.0%) | 0.038 * | 13 |

| Post-Transplant Diabetes (%) | 21 (10.8%) | 12 (9.9%) | 9 (13.2%) | 0.486 | |

| Acute Nephrotoxic event (%) | 27 (15.8%) | 17 (15.5%) | 9 (15.8%) | 0.955 | 23 |

| Rejection episode | 37 (20.1%) | 15 (13.5%) | 22 (32.4%) | 0.003 * | 10 |

| Primary kidney disease | |||||

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 16 (8.3%) | 10 (8.3%) | 6 (8.8%) | 0.219 # | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 4 (2.1%) | 1 (0.8%) | 3 (4.4%) | ||

| Hypertension | 88 (45.4%) | 52 (43.0%) | 34 (50.0%) | ||

| Polycystic kidney disease | 7 (3.61%) | 3 (2.5%) | 4 (5.9%) | ||

| Other | 6 (3.1) | 4 (3.3%) | 1 (1.5%) | ||

| Unknown | 73 (37.6%) | 51 (42.2%) | 20 (29.4%) |

| Graft Survival | ||||

| Risk factors | Unadjusted | Adjusted # | ||

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Rejection YES (Ref NO) | 2.16 (1.25–3.74) | 0.006 | 2.25 (1.13–4.47) | 0.021 |

| Age at transplant (years) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 0.010 | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) | 0.006 |

| Female gender (Ref Male) | 0.70 (0.40–1.21) | 0.203 | - | |

| Pre-transplant diabetes YES (Ref NO) | 3.01 (0.42–21.88) | 0.275 | - | |

| Post-transplant diabetes | 1.40 (0.69–2.86) | 0.350 | - | |

| Pre-transplant hypertension YES (Ref NO) | 3.06 (0.42–22.24) | 0.268 | - | |

| Delayed graft function | 1.29 (0.73–2.27) | 0.384 | - | |

| Patient Survival | ||||

| Risk Factors | Unadjusted | Adjusted $ | ||

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age at transplant (years) | 1.03 (1.00–1.07) | 0.050 | 1.06 (1.02–1.11) | 0.005 |

| Female gender (Ref: Male) | 0.69 (0.34–1.40) | 0.304 | - | |

| Pre-transplant diabetes YES (Ref: NO) | 4.66 (0.63–34.42) | 0.131 | - | |

| Post-transplant diabetes YES (Ref: NO) | 0.45 (0.11–1.87) | 0.271 | - | |

| Pre-transplant hypertension YES (Ref: NO) | 1.58 (0.21–11.67) | 0.654 | - | |

| Risk Factors | Unadjusted | Adjusted # | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number at Risk | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Number at Risk | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| 1-year graft survival | ||||||

| $TAC achieved in 1st month YES (Ref: not achieved) | n = 159 | 1.63 (0.48–5.56) | 0.435 | n = 146 | 1.45 (0.41–5.11) | 0.566 |

| Age at transplant | n = 184 | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | 0.103 | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 0.119 | |

| $HB target achieved at month 1 | n = 161 | 0.37 (0.15–0.93) | 0.035 | .0.39 (0.14–1.10) | 0.077 | |

| $TAC maintained for 12 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | n = 140 | 2.09 (0.27–16.11) | 0.477 | n = 136 | 2.31 (0.30–18.04) | 0.425 |

| Age at transplant | n = 184 | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | 0.103 | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 0.127 | |

| $HB maintained for 12 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | n = 164 | 0.29 (0.10–0.80) | 0.018 | 0.73 (0.19–2.77) | 0.646 | |

| $Co-medications in preceding 12 months YES | n = 179 | 0.19 (0.03–1.40) | 0.103 | 0.37 (0.05–2.90) | 0.346 | |

| 2-year graft survival | ||||||

| $TAC maintained for 24 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | n = 148 | 1.55 (0.46–5.17) | 0.478 | n = 144 | 1.66 (0.49–5.64) | 0.417 |

| Age at transplant | n = 184 | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) | 0.034 | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 0.030 | |

| $HB maintained for 24 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | n = 166 | 0.30 (0.14–0.63) | 0.002 | 0.52 (0.21–1.27) | 0.148 | |

| $Co-medications in preceding 24 months YES | n = 179 | 0.12 (0.02–0.89) | 0.038 | 0.22 (0.03–1.62) | 0.136 | |

| 3-year graft survival | ||||||

| $TAC maintained for 36 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | n = 149 | 0.69 (0.28–1.69) | 0.420 | n = 145 | 0.71 (0.29–1.77) | 0.464 |

| Age at transplant | n = 184 | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) | 0.020 | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 0.044 | |

| $HB maintained for 36 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | n = 166 | 0.17 (0.09–0.34) | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.14–0.69) | 0.004 | |

| $Co-medications in preceding 36 months YES | n= 179 | 0.09 (0.01–0.69) | 0.020 | 0.18 (0.02–1.37) | 0.098 | |

| 4-year graft survival | ||||||

| $TAC maintained for 48 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | 151 | 0.83 (0.35–2.00) | 0.682 | n = 149 | 0.87 (0.36–2.11) | 0.757 |

| Age at transplant | 184 | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.011 | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) | 0.032 | |

| $HB maintained for 48 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | 168 | 0.21 (0.11–0.41) | <0.001 | 0.29 (0.14–0.59) | 0.001 | |

| 5-year graft survival | ||||||

| $TAC maintained for 60 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | n = 151 | 0.75 (0.36–1.55) | 0.432 | n = 147 | 0.77 (0.37–1.62) | 0.493 |

| Age at transplant | n = 184 | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 0.010 | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.012 | |

| $HB maintained for 6 0 months YES (Ref: not maintained) | n = 168 | 0.17 (0.09–0.30) | <0.001 | 0.22 (0.12–0.43) | <0.001 | |

| Co-medications in preceding 60 months YES | n = 179 | 0.26 (0.08–0.85) | 0.025 | 0.53 (0.16–1.78) | 0.304 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hussaini, S.A.; Dickens, C.; Makgoro, C.; Dix-Peek, T.; Munir, B.; Perumala, J.; Patel, S.; Goolam, Q.; Paget, G.; Waziri, B.; et al. Clinical Characteristics, Long-Term Pharmacokinetics, and Outcomes in Kidney Transplant Recipients from an African Tertiary Centre: A 10-Year Single-Centre Retrospective Review. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010132

Hussaini SA, Dickens C, Makgoro C, Dix-Peek T, Munir B, Perumala J, Patel S, Goolam Q, Paget G, Waziri B, et al. Clinical Characteristics, Long-Term Pharmacokinetics, and Outcomes in Kidney Transplant Recipients from an African Tertiary Centre: A 10-Year Single-Centre Retrospective Review. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010132

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussaini, Sadiq Aliyu, Caroline Dickens, Confidence Makgoro, Therese Dix-Peek, Badar Munir, Jeevan Perumala, Simran Patel, Qaiser Goolam, Graham Paget, Bala Waziri, and et al. 2026. "Clinical Characteristics, Long-Term Pharmacokinetics, and Outcomes in Kidney Transplant Recipients from an African Tertiary Centre: A 10-Year Single-Centre Retrospective Review" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010132

APA StyleHussaini, S. A., Dickens, C., Makgoro, C., Dix-Peek, T., Munir, B., Perumala, J., Patel, S., Goolam, Q., Paget, G., Waziri, B., & Duarte, R. (2026). Clinical Characteristics, Long-Term Pharmacokinetics, and Outcomes in Kidney Transplant Recipients from an African Tertiary Centre: A 10-Year Single-Centre Retrospective Review. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010132