Enhancing the Solubility and Antibacterial Efficacy of Sulfamethoxazole by Incorporating Functionalized PLGA and Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles into the Crystal Structure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials, Chemicals, and Methods

2.2. Bacterial Propagation

2.3. Synthesis of SMX-nfPLGA

2.4. Synthesis of SMZ-nGO

2.5. Antibacterial Studies

2.6. Drug Formulation Property Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Material Characterization

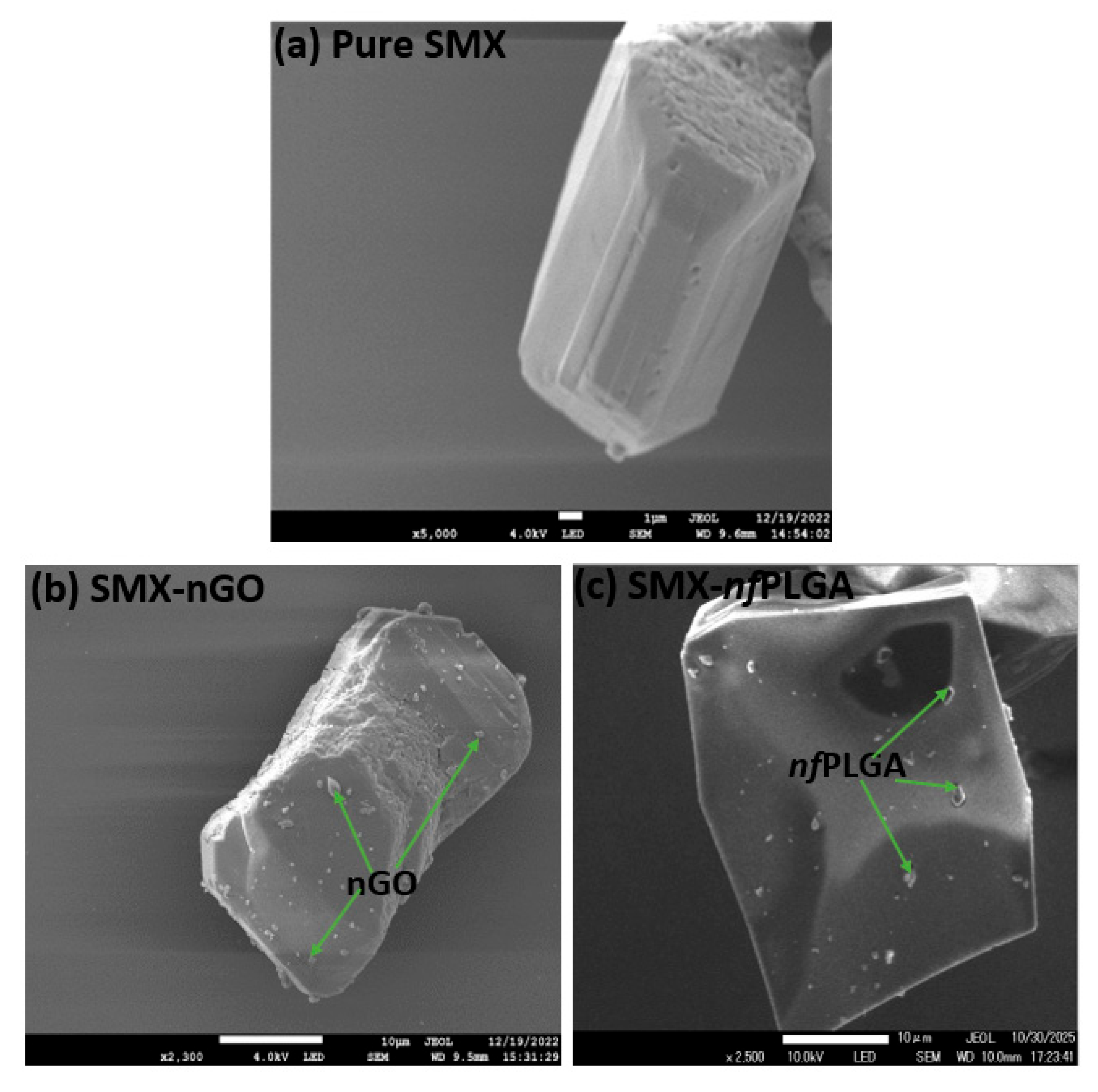

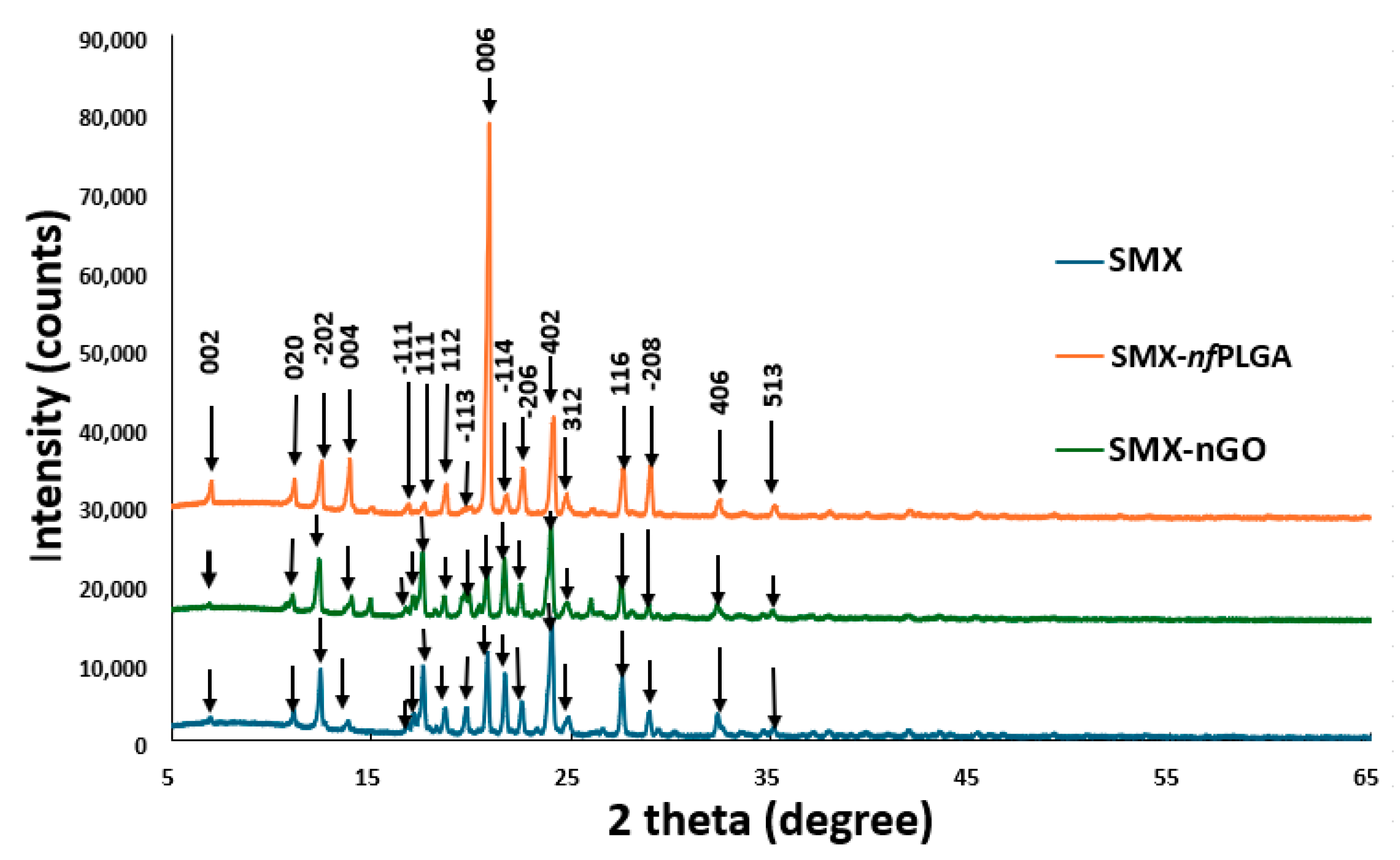

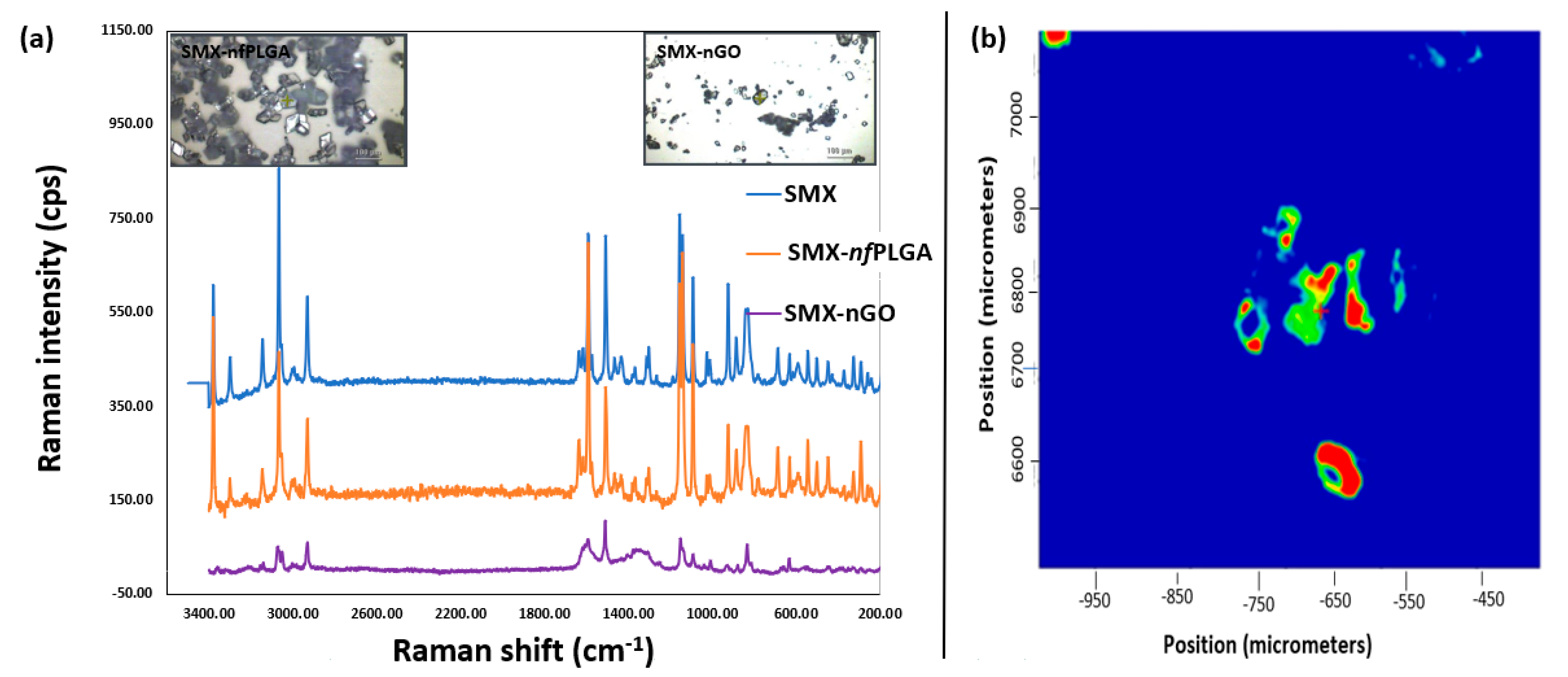

3.1.1. Morphology and Physicochemical Property Analysis

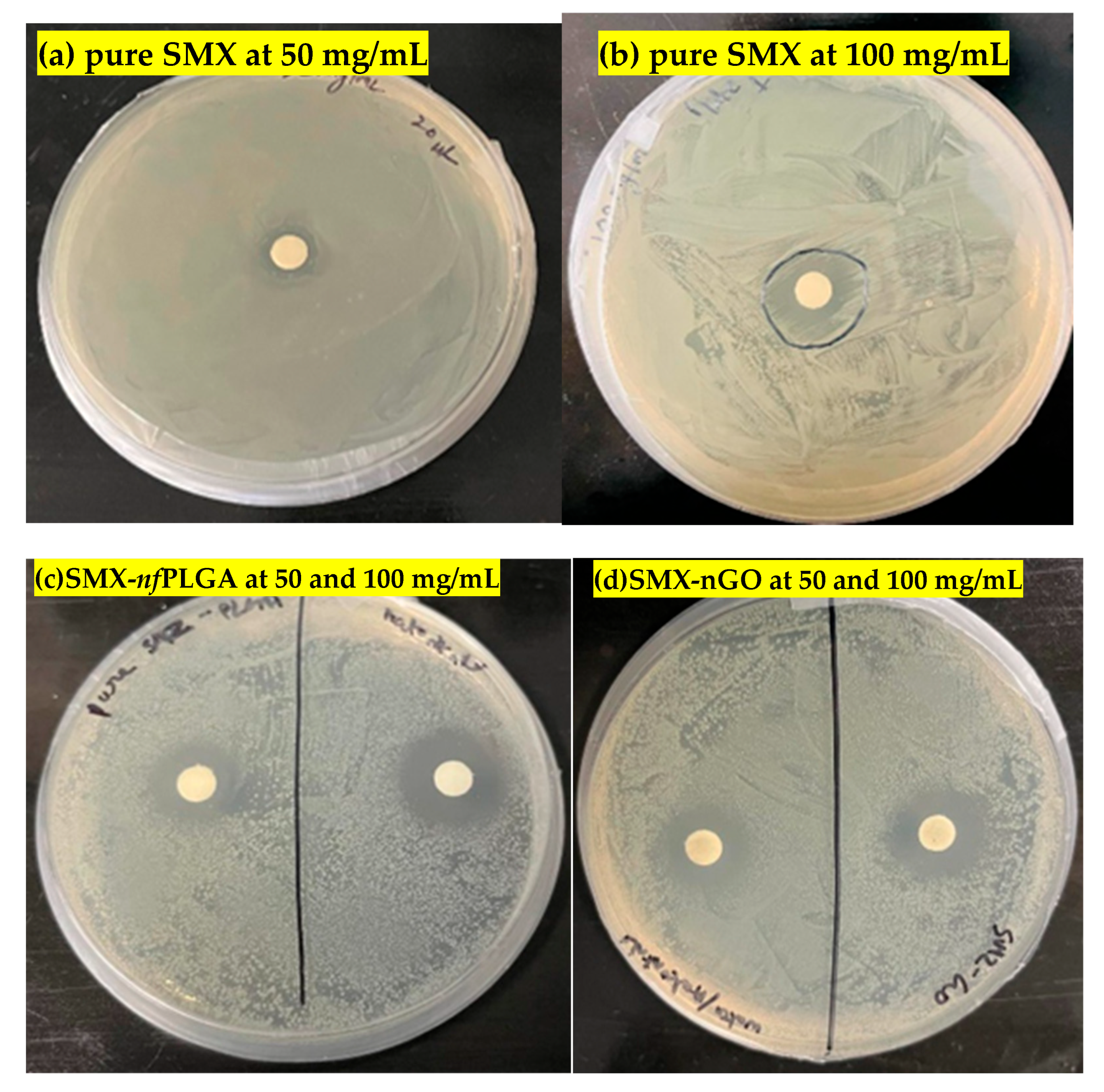

3.1.2. Antibacterial Assays

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laxminarayan, R. Antibiotic effectiveness: Balancing conservation against innovation. Science 2014, 345, 1299–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, M.I.; Truman, A.W.; Wilkinson, B. Antibiotics: Past, present and future. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 51, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Cunha, B.R.; Fonseca, L.P.; Calado, C.R.C. Antibiotic Discovery: Where Have We Come from, Where Do We Go? Antibiotics 2019, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieri, M.; Kumar, K.; Boutin, A. Antibiotic resistance. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwobodo, D.C.; Ugwu, M.C.; Anie, C.O.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T.S.; Ikem, J.C.; Chigozie, U.V.; Saki, M. Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Hussein, S.; Qurbani, K.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Fareeq, A.; Mahmood, K.A.; Mohamed, M.G. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 2, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.; Karlén, A. Discovery and preclinical development of new antibiotics. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2014, 119, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Buitimea, A.; Garza-Cárdenas, C.R.; Garza-Cervantes, J.A.; Lerma-Escalera, J.A.; Morones-Ramírez, J.R. The demand for new antibiotics: Antimicrobial peptides, nanoparticles, and combinatorial therapies as future strategies in antibacterial agent design. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezerlou, A.; Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Ehsani, A. Nanoparticles and their antimicrobial properties against pathogens including bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 123, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyers, M.; Wright, G.D. Drug combinations: A strategy to extend the life of antibiotics in the 21st century. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Li, X.; Pan, Q.; Wang, K.; Liu, N.; Yutao, W.; Zhang, Y. Nanotechnology-based approaches for antibacterial therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 279, 116798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.; Giuliano, E.; Venkateswararao, E.; Fresta, M.; Bulotta, S.; Awasthi, V.; Cosco, D. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery to solid tumors. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 601626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, T.M.; Mahapatra, D.K.; Esmaeili, A.; Piszczyk, Ł.; Hasanin, M.S.; Kattali, M.; Haponiuk, J.; Thomas, S. Nanoparticles: Taking a Unique Position in Medicine. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begines, B.; Ortiz, T.; Pérez-Aranda, M.; Martínez, G.; Merinero, M.; Argüelles-Arias, F.; Alcudia, A. Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery: Recent Developments and Future Prospects. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, O.; Altamimi, A.S.A.; Nadeem, M.S.; Alzarea, S.I.; Almalki, W.H.; Tariq, A.; Mubeen, B.; Murtaza, B.N.; Iftikhar, S.; Riaz, N.; et al. Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery: From History to Therapeutic Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Huang, H.; Yin, M.; Liu, H. Applications of liposomes and lipid nanoparticles in cancer therapy: Current advances and prospects. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsen, E.; El-Borady, O.M.; Mohamed, M.B.; Fahim, I.S. Synthesis and characterization of ciprofloxacin loaded silver nanoparticles and investigation of their antibacterial effect. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2020, 13, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, P.; Baliou, S.; Samonis, G. Nanotechnology in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Antibiotic-Resistant Infections. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, N.; Devnarain, N.; Omolo, C.A.; Fasiku, V.; Jaglal, Y.; Govender, T. Surface modification of nano-drug delivery systems for enhancing antibiotic delivery and activity. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 14, e1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.I.; Dias, A.M.; Zille, A. Synergistic effects between metal nanoparticles and commercial antimicrobial agents: A review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 3030–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kesarla, R.; Omri, A. Formulation strategies to improve the bioavailability of poorly absorbed drugs with special emphasis on self-emulsifying systems. ISRN Pharm. 2013, 2013, 848043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, E.E. Sulfonamide antibiotics. Prim. Care Update OB/GYNS 1998, 5, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovung, A.; Bhattacharyya, J. Sulfonamide drugs: Structure, antibacterial property, toxicity, and biophysical interactions. Biophys. Rev. 2021, 13, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, J.L.; Baquero, F. Interactions among strategies associated with bacterial infection: Pathogenicity, epidemicity, and antibiotic resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 647–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary tract infections: Epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangcuangco, L.M.; Alejandria, M.; Henson, K.E.; Alfaraz, L.; Ata, R.M.; Lopez, M.; Saniel, M. Prevalence and risk factors for trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole-resistant Escherichia coli among women with acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in a developing country. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagaglia, C.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Maurizi, L.; Nicoletti, M.; Longhi, C. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Strains—New Strategies for an Old Pathogen. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Patel, P.; Shah, S.; Patel, K. Nanocomposites in focus: Tailoring drug delivery for enhanced therapeutic outcomes. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, N.; Joo, S.W.; Mandal, T.K. Nanomaterial-Based Strategies to Combat Antibiotic Resistance: Mechanisms and Applications. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrange, H.; Najda, A.; Bains, A.; Gruszecki, R.; Chawla, P.; Tosif, M.M. Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticle as a Novel Antibiotic Carrier for the Direct Delivery of Antibiotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.A.; Patil, R.H. Metal nanoparticles as inhibitors of enzymes and toxins of multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Med. 2023, 2, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-López, E.; Gomes, D.; Esteruelas, G.; Bonilla, L.; Lopez-Machado, A.L.; Galindo, R.; Cano, A.; Espina, M.; Ettcheto, M.; Camins, A.; et al. Metal-Based Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: An Overview. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estelrich, J.; Escribano, E.; Queralt, J.; Busquets, M.A. Iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetically-guided and magnetically-responsive drug delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 8070–8101. [Google Scholar]

- Bruna, T.; Maldonado-Bravo, F.; Jara, P.; Caro, N. Silver Nanoparticles and Their Antibacterial Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalavarshini, S.; Ranjani, S.; Hemalatha, S. Gold nanoparticles: A novel paradigm for targeted drug delivery. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2023, 53, 449–459. [Google Scholar]

- Algadi, H.; Alhoot, M.A.; Al-Maleki, A.R.; Purwitasari, N. Effects of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles against Biofilm-Forming Bacteria: A Systematic Review. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 1748–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.; Salman, A.; Khan, Z.; Khan, S.; Krishnaraj, C.; Yun, S.-I. Metallic Nanoparticles: A Promising Arsenal against Antimicrobial Resistance—Unraveling Mechanisms and Enhancing Medication Efficacy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Mitra, S. Microwave Synthesis of Nanostructured Functionalized Polylactic Acid (nfPLA) for Incorporation Into a Drug Crystals to Enhance Their Dissolution. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 112, 2260–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Mitra, S. Synthesis of Microwave Functionalized, Nanostructured Polylactic Co-Glycolic Acid (nfPLGA) for Incorporation into Hydrophobic Dexamethasone to Enhance Dissolution. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 943. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.S.; Mitra, S. Effect of nano graphene oxide (nGO) incorporation on the lipophilicity of hydrophobic drugs. Hybrid Adv. 2023, 3, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Renner, F.; Azizighannad, S.; Mitra, S. Direct incorporation of nano graphene oxide (nGO) into hydrophobic drug crystals for enhanced aqueous dissolution. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 189, 110827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Renner, F.; Foster, K.; Oderinde, M.S.; Stefanski, K.; Mitra, S. Hydrophilic and Functionalized Nanographene Oxide Incorporated Faster Dissolving Megestrol Acetate. Molecules 2021, 26, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Mitra, S. Development of nano structured graphene oxide incorporated dexamethasone with enhanced dis-solution. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2022, 47, 100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kann, B.; Offerhaus, H.L.; Windbergs, M.; Otto, C. Raman microscopy for cellular investigations—From single cell imaging to drug carrier uptake visualization. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 89, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, T.; Schäfer, N.; Levcenko, S.; Rissom, T.; Abou-Ras, D. Orientation-distribution mapping of polycrystalline materials by Raman microspectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sl No. | Materials | Material Concentration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disk Diffusion Assays (mg/mL) | O.D. Measurements (µg/mL) | ||

| 1 | Pure SMX | 50, 100 | 100 |

| 2 | Pure PLGA | - | 100 |

| 3 | Pure GO | - | 100 |

| 4 | SMX-nfPLGA | 50, 100 | 100 |

| 5 | SMX-nGO | 50, 100 | 100 |

| Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) Formulations | Aqueous Solubility (25 °C) (mg/mL) | Partitioning LogP | Melting Temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure SMX | 0.029 | 1.40 | 172.51 |

| SMX-nGO | 0.063 | 0.86 | 170.11 |

| SMX-nfPLGA | 0.058 | 0.92 | 171.14 |

| Serial No. | Concentration (mg/mL) | Inhibition Zone (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Pure SMX | ||

| 1 | 50 | 10 |

| 2 | 100 | 15 |

| SMX-nfPLGA | ||

| 3 | 50 | 16 |

| 4 | 100 | 23 |

| SMX-nGO | ||

| 5 | 50 | 15 |

| 6 | 100 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Islam, M.S.; Gupta, I.; Farinas, E.T.; Mitra, S. Enhancing the Solubility and Antibacterial Efficacy of Sulfamethoxazole by Incorporating Functionalized PLGA and Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles into the Crystal Structure. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111460

Islam MS, Gupta I, Farinas ET, Mitra S. Enhancing the Solubility and Antibacterial Efficacy of Sulfamethoxazole by Incorporating Functionalized PLGA and Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles into the Crystal Structure. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(11):1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111460

Chicago/Turabian StyleIslam, Mohammad Saiful, Indrani Gupta, Edgardo T. Farinas, and Somenath Mitra. 2025. "Enhancing the Solubility and Antibacterial Efficacy of Sulfamethoxazole by Incorporating Functionalized PLGA and Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles into the Crystal Structure" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 11: 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111460

APA StyleIslam, M. S., Gupta, I., Farinas, E. T., & Mitra, S. (2025). Enhancing the Solubility and Antibacterial Efficacy of Sulfamethoxazole by Incorporating Functionalized PLGA and Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles into the Crystal Structure. Pharmaceutics, 17(11), 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111460