Synthesis and Preliminary Characterization of Putative Anle138b-Centered PROTACs against α-Synuclein Aggregation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Medicinal Chemistry

2.1.1. General

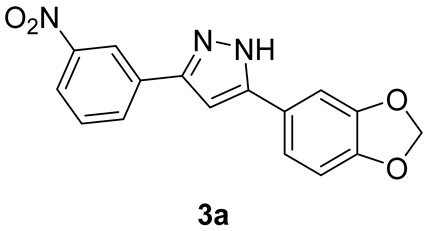

2.1.2. Synthesis of m-Nitro-Substituted Diphenylpyrazole 3a

Analytical Characterization

2.1.3. Synthesis of Anle138b-Based m-Anilino Derivative 1a

Analytical Characterization

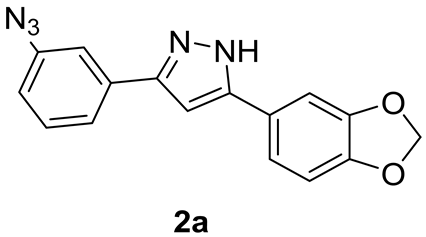

2.1.4. Synthesis of Anle138b-Based m-Azido 2a

Analytical Characterization

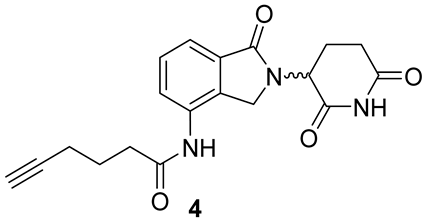

2.1.5. Synthesis of Lenalidomide Alkynylamide Linker-CRBN Ligand Construct 4

Analytical Characterization

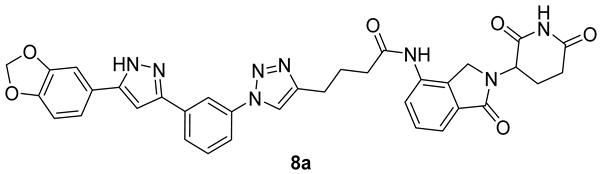

2.1.6. Synthesis of Anle138b m-Triazole Connected Lenalidomide PROTAC 8a

Analytical Characterization

2.2. Biological Studies

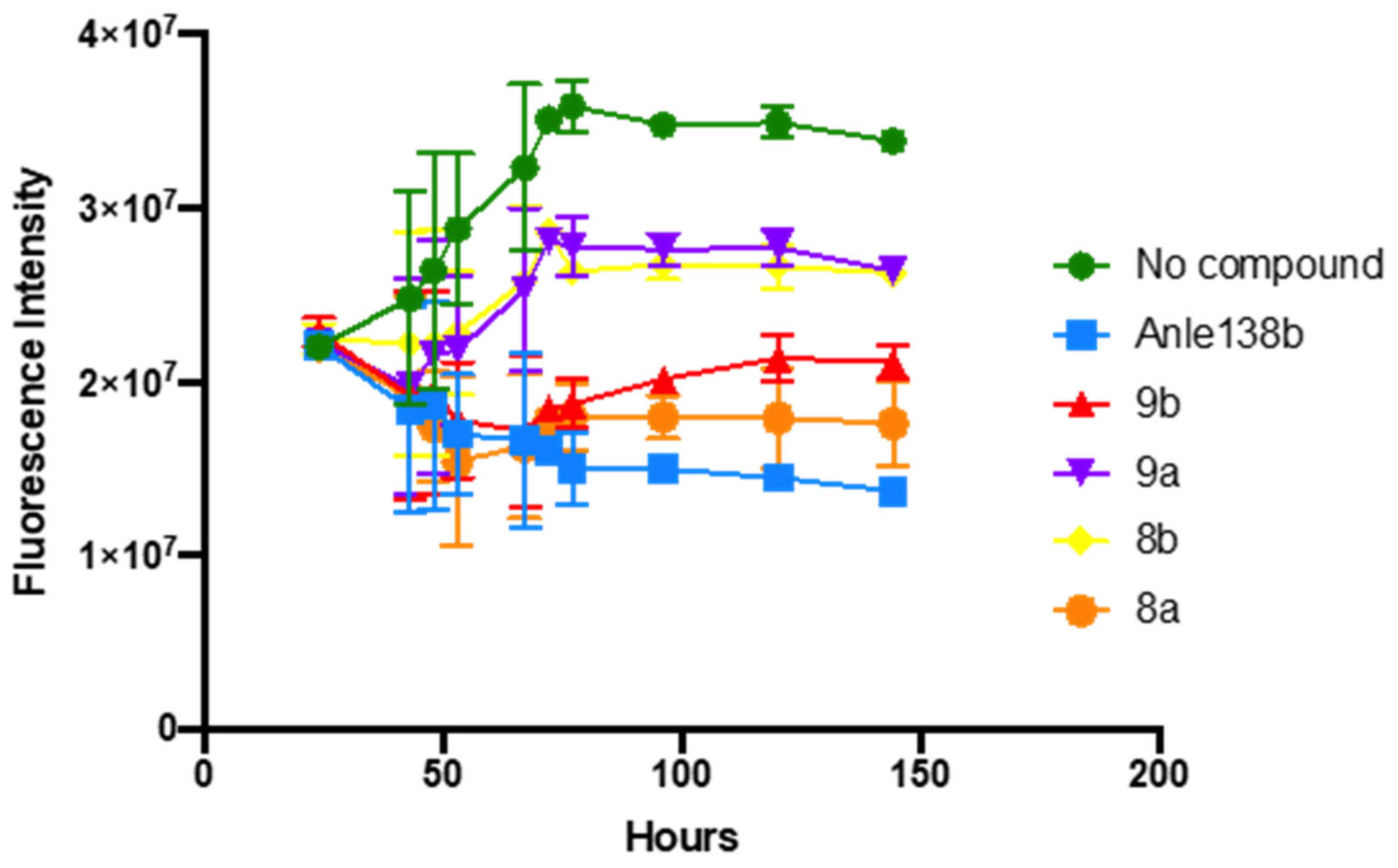

2.2.1. In Vitro Thioflavin T-Based Assay for αSyn Aggregation

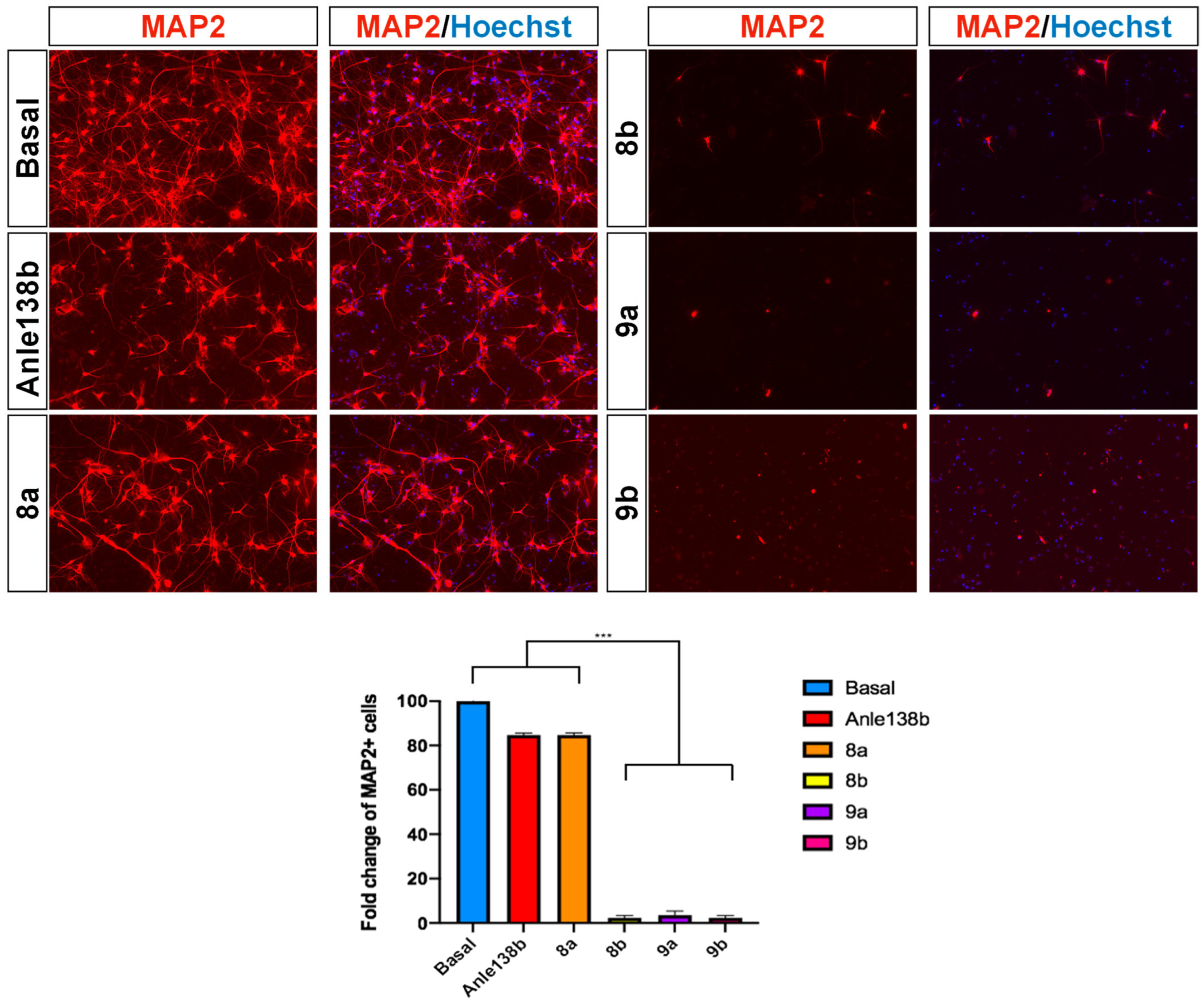

2.2.2. Cytotoxic Effects of Anle138b-PROTAC Constructs on 4xSNCA iPSC-Derived Neurons

2.2.3. Cellular Assay for αSyn Aggregation on Patient-Derived DANs

3. Results

3.1. Medicinal Chemistry

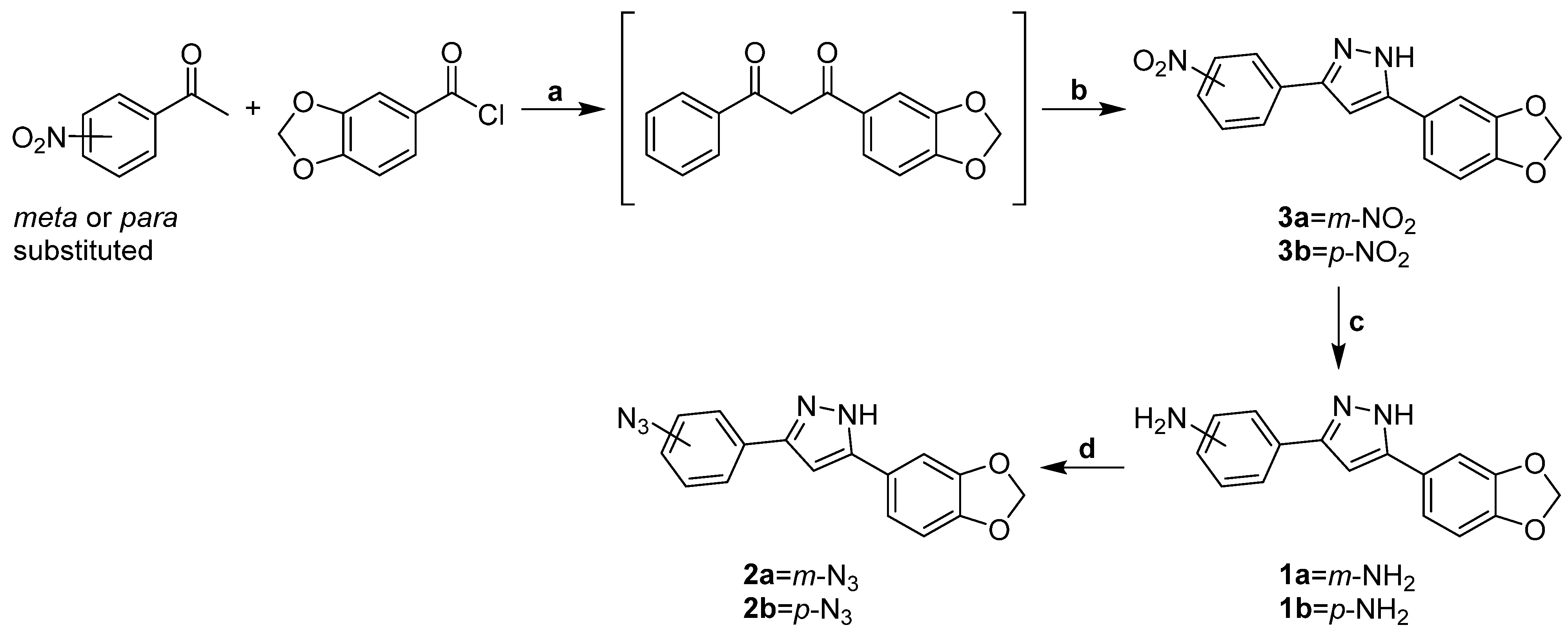

3.1.1. Rational Design and Synthesis of m/p Anle138b-Based Analogues 2a,b Suitable for PROTAC Assembly

3.1.2. Synthesis of m/p Anle138b Analogues 1a,b, 2a,b for PROTAC Assembly

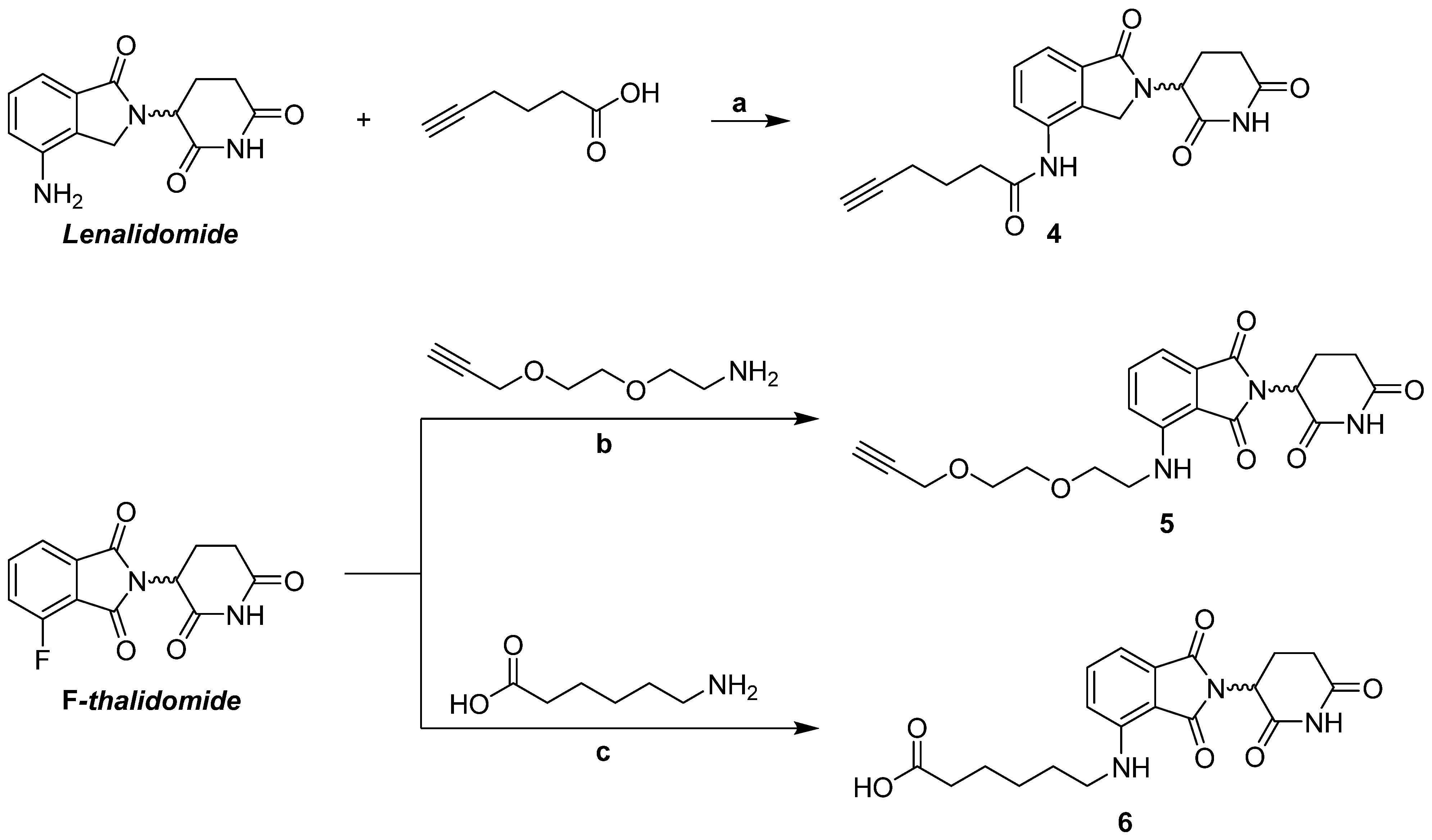

3.1.3. Synthesis of Thalidomide-/Lenalidomide-Linker Constructs 4–6 for Coupling with m/p Anle138b Analogues

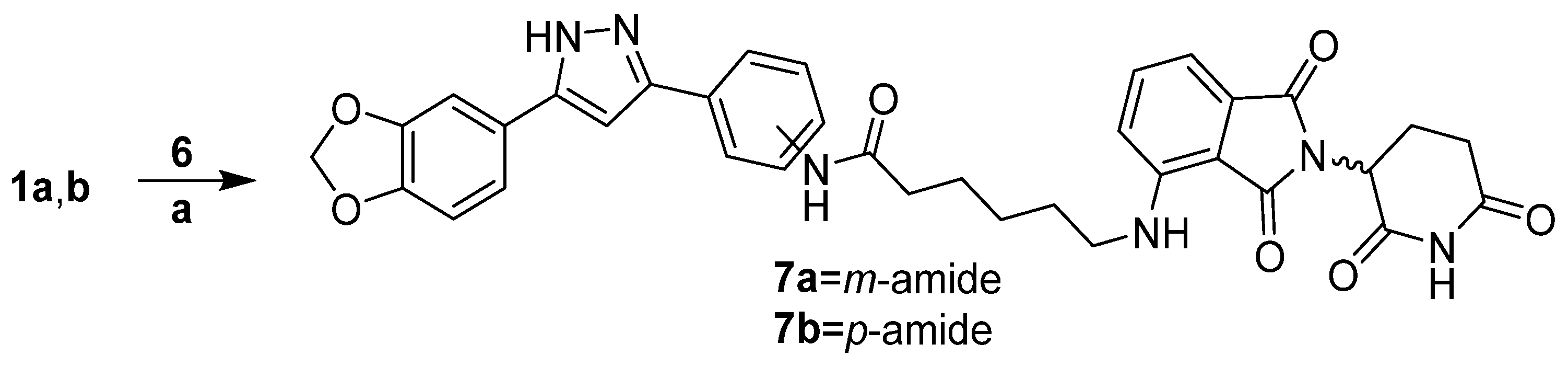

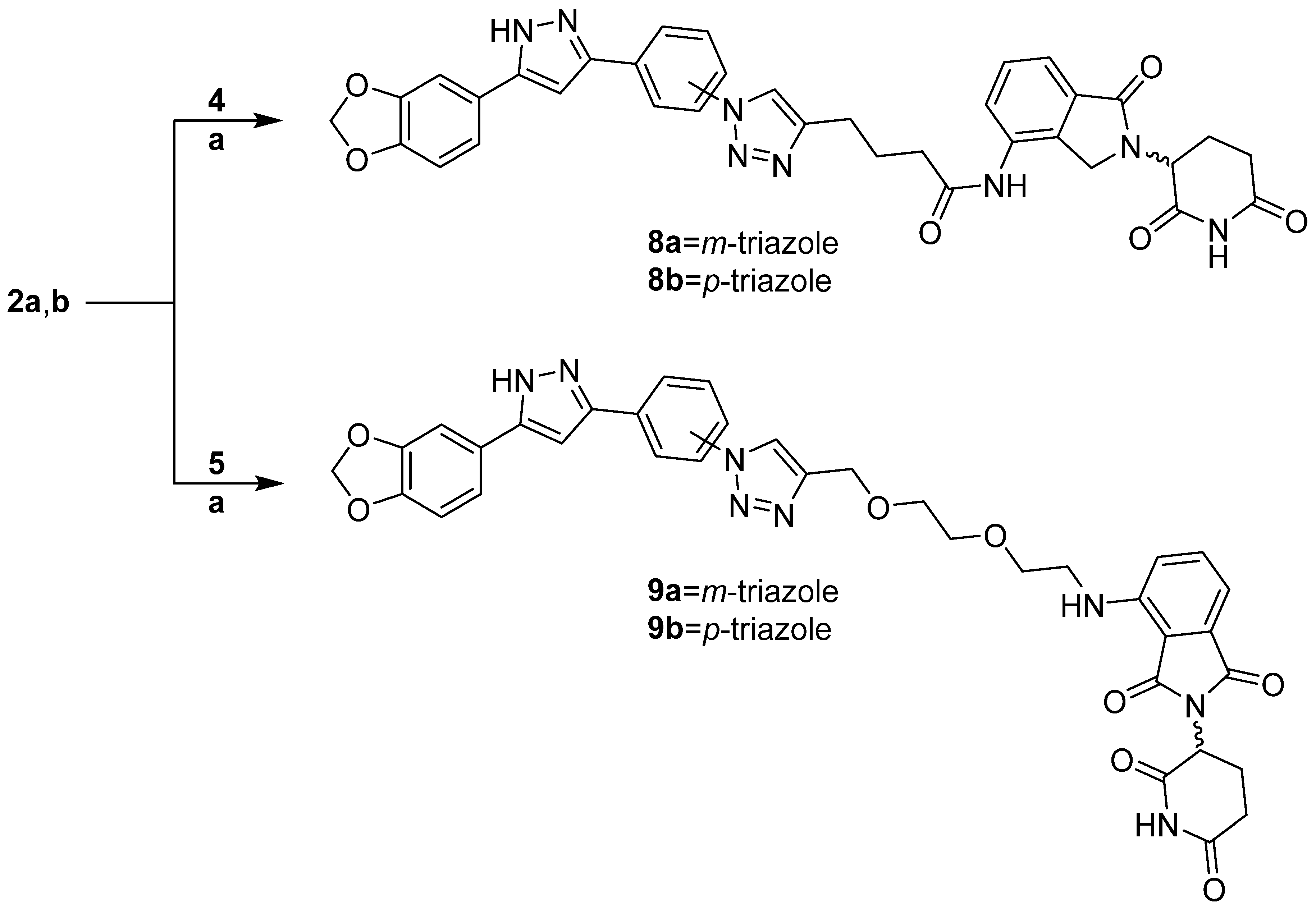

3.1.4. PROTAC Hybrid Assembly: Click Reaction- and Amide-Based Strategies to 7a,b–9a,b

3.2. Biology Studies

3.2.1. In Vitro αSyn Aggregation Assay

3.2.2. Cellular Assay for αSyn Aggregation on Patient-Derived Dopaminergic Neurons

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wareham, L.K.; Liddelow, S.A.; Temple, S.; Benowitz, L.I.; Di Polo, A.; Wellington, C.; Goldberg, J.L.; He, Z.; Duan, X.; Bu, G.; et al. Solving neurodegeneration: Common mechanisms and strategies for new treatments. Mol. Neurodeg. 2022, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Han, X.X.; Yang, X.M.; Zhou, S.L. Proteolysis Targeting Chimera Technology: A Novel Strategy for Treating Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbet, R.M.; Polanco, J.C.; Ittner, L.M.; Götz, J. Tau Aggregation and Its Interplay with Amyloid-β. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 129, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Z.L.; Brito, R.M.M. Structure and Aggregation Mechanisms in Amyloids. Molecules 2020, 25, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.A.; Poirier, M. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 2004, 10 (Suppl. S7), S10–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakes, R.; Spillantini, M.G.; Goedert, M. Identification of Two Distinct Synucleins from Human Brain. FEBS Lett. 1994, 345, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, J.; Chamberlain, S.G.; Owen, D.; Mott, H.R. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins and Membranes: A Marriage of Convenience for Cell Signalling? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 2669–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M. Alpha-Synuclein and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymeropoulos, M.H.; Lavedan, C.; Leroy, E.; Ide, S.E.; Dehejia, A.; Dutra, A.; Dutra, A.; Pike, B.; Root, H.; Rubenstein, J.; et al. Mutation in the α-Synuclein Gene Identified in Families with Parkinson’s Disease. Science 1997, 276, 2045–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, F.; Yung, K.K.L.; Zhang, S.; Qu, S. Effects of α-Synuclein-Associated Post-Translational Modifications in Parkinson’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekoohi, S.; Rajasekaran, S.; Patel, D.; Yang, S.; Liu, W.; Huang, S.; Yu, X.; Witt, S.N. Knocking out alpha-synuclein in melanoma cells dysregulates cellular iron metabolism and suppresses tumor growth. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Xu, K. Alpha-synuclein contributes to malignant progression of human meningioma via the Akt/mTOR pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2016, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwabufo, C.K.; Aigbogun, O.P. Diagnostic and therapeutic agents that target alpha-synuclein in Parkinson disease. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 5762–5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Ryazanov, S.; Leonov, A.; Levin, J.; Shi, S.; Schmidt, F.; Prix, C.; Pan-Montojo, F.; Bertsch, U.; Mitteregger-Kretzschmar, G.; et al. Anle138b: A Novel Oligomer Modulator for Disease-Modifying Therapy of Neurodegenerative Diseases Such as Prion and Parkinson’s Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 125, 795–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, J.; Sing, N.; Melbourne, S.; Morgan, A.; Mariner, C.; Spillantini, M.G.; Wegrzynowicz, M.; Dalley, J.W.; Langer, S.; Ryazanov, S.; et al. Safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of the oligomer modulator anle138b with exposure levels sufficient for therapeutic efficacy in a murine Parkinson model: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1a trial. eBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeg, A.A.; Reiner, A.M.; Schmidt, F.; Schueder, F.; Ryazanov, S.; Ruf, V.C.; Giller, K.; Becker, S.; Leonov, A.; Griesinger, C.; et al. Anle138b and Related Compounds Are Aggregation Specific Fluorescence Markers and Reveal High Affinity Binding to α-Synuclein Aggregates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1850, 1884–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, J.; Schmidt, F.; Boehm, C.; Prix, C.; Bötzel, K.; Ryazanov, S.; Leonov, A.; Griesinger, C.; Giese, A. The Oligomer Modulator Anle138b Inhibits Disease Progression in a Parkinson Mouse Model Even with Treatment Started after Disease Onset. Acta Neuropathol. 2014, 127, 779–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heras-Garvin, A.; Weckbecker, D.; Ryazanov, S.; Leonov, A.; Griesinger, C.; Giese, A.; Wenning, G.K.; Stefanova, N. Anle138b Modulates α-Synuclein Oligomerization and Prevents Motor Decline and Neurodegeneration in a Mouse Model of Multiple System Atrophy. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, A.M.; Shabek, N.; Ciechanover, A. The Predator Becomes the Prey: Regulating the Ubiquitin System by Ubiquitylation and Degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, T.; Li, S.; Ye, J.; Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Deng, M.; Ke, D.; et al. A Novel Small-Molecule PROTAC Selectively Promotes Tau Clearance to Improve Cognitive Functions in Alzheimer-like Models. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5279–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J. The Proteasome: Structure, function, and role in the cell. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2003, 29, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondeson, D.P.; Mares, A.; Smith, I.E.D.; Ko, E.; Campos, S.; Miah, A.H.; Mulholland, K.E.; Routly, N.; Buckley, D.L.; Gustafson, J.L.; et al. Catalytic in vivo Protein Knockdown by Small-Molecule PROTACs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarasinghe, K.T.G.; Crews, C.M. Targeted Protein Degradation: A Promise for Undruggable Proteins. Cell Chem. Biol. 2021, 28, 934–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Ren, X.; Xue, F.; He, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J. Specific Knockdown of a-Synuclein by Peptide-Directed Proteasome Degradation Rescued Its Associated Neurotoxicity. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kargbo, R.B. PROTAC Compounds Targeting α-Synuclein Protein for Treating Neurogenerative Disorders: Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 1086–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Handa, H. Molecular mechanisms of thalidomide and its derivatives. Proc. Acad. Jpn. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2020, 96, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannielli, A.; Luoni, M.; Giannelli, S.G.; Ferese, R.; Ordazzo, G.; Fossati, M.; Raimondi, A.; Opazo, F.; Corti, O.; Prehn, J.H.M.; et al. Modeling native and seeded Synuclein aggregation and related cellular dysfunctions in dopaminergic neurons derived by a new set of isogenic iPSC lines with SNCA multiplications. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.C.; Joshi, P.; Chauhan, S.S.; Nigam, S. Synthesis of novel pyrazole derivatives from dyaryl-1,3-diketones (Part II). Heter. Commun. 2004, 10, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wordehoff, M.M.; Hoyer, W. α-Synuclein aggregation monitored by thioflavin T fluorescence assay. Bio. Protoc. 2018, 8, e2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonandi, E.; Christodoulou, M.S.; Fumagalli, G.; Perdicchia, D.; Rastelli, G.; Passarella, D. The 1,2,3-Triazole Ring as a Bioisostere in Medicinal Chemistry. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 1572–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurz, R.P.; Dellamaggiore, K.; Dou, H.; Javier, N.; Lo, M.-C.; McCarter, J.D.; Mohl, D.; Sastri, C.; Lipford, J.R.; Cee, V.J. A “Click Chemistry Platform” for the Rapid Synthesis of Bispecific Molecules for Inducing Protein Degradation. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebraud, H.; Wright, D.J.; Johnson, C.N.; Heightman, T.D. Protein Degradation by In-Cell Self-Assembly of Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, S.T.; Natarajan, S.R. 1,3-Diketones from Acid Chlorides and Ketones: A Rapid and General One-Pot Synthesis of Pyrazoles. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 2675–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolmaleki, A.; Ghasemi, J.B. Dual-acting of Hybrid Compounds—A New Dawn in the Discovery of Multi-target Drugs: Lead Generation Approaches. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 1096–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingozzi, M.; Manzoni, L.; Arosio, D.; Corso, A.D.; Manzotti, M.; Innamorati, F.; Pignataro, L.; Lecis, D.; Delia, D.; Seneci, P.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of dual action cyclo-RGD/SMAC mimetic conjugates targeting αvβ3/αvβ5 integrins and IAP proteins. Org. Mol. Biochem. 2014, 12, 3288–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Attoub, S.; Singh, M.N.; Martin, F.L.; El-Agnaf, O.M.A. g-Synuclein and the progression of cancer. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 3419–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pedrini, M.; Iannielli, A.; Meneghelli, L.; Passarella, D.; Broccoli, V.; Seneci, P. Synthesis and Preliminary Characterization of Putative Anle138b-Centered PROTACs against α-Synuclein Aggregation. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15051467

Pedrini M, Iannielli A, Meneghelli L, Passarella D, Broccoli V, Seneci P. Synthesis and Preliminary Characterization of Putative Anle138b-Centered PROTACs against α-Synuclein Aggregation. Pharmaceutics. 2023; 15(5):1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15051467

Chicago/Turabian StylePedrini, Martina, Angelo Iannielli, Lorenzo Meneghelli, Daniele Passarella, Vania Broccoli, and Pierfausto Seneci. 2023. "Synthesis and Preliminary Characterization of Putative Anle138b-Centered PROTACs against α-Synuclein Aggregation" Pharmaceutics 15, no. 5: 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15051467

APA StylePedrini, M., Iannielli, A., Meneghelli, L., Passarella, D., Broccoli, V., & Seneci, P. (2023). Synthesis and Preliminary Characterization of Putative Anle138b-Centered PROTACs against α-Synuclein Aggregation. Pharmaceutics, 15(5), 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15051467