Orally Administered Amphotericin B Nanoformulations: Physical Properties of Nanoparticle Carriers on Bioavailability and Clinical Relevance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

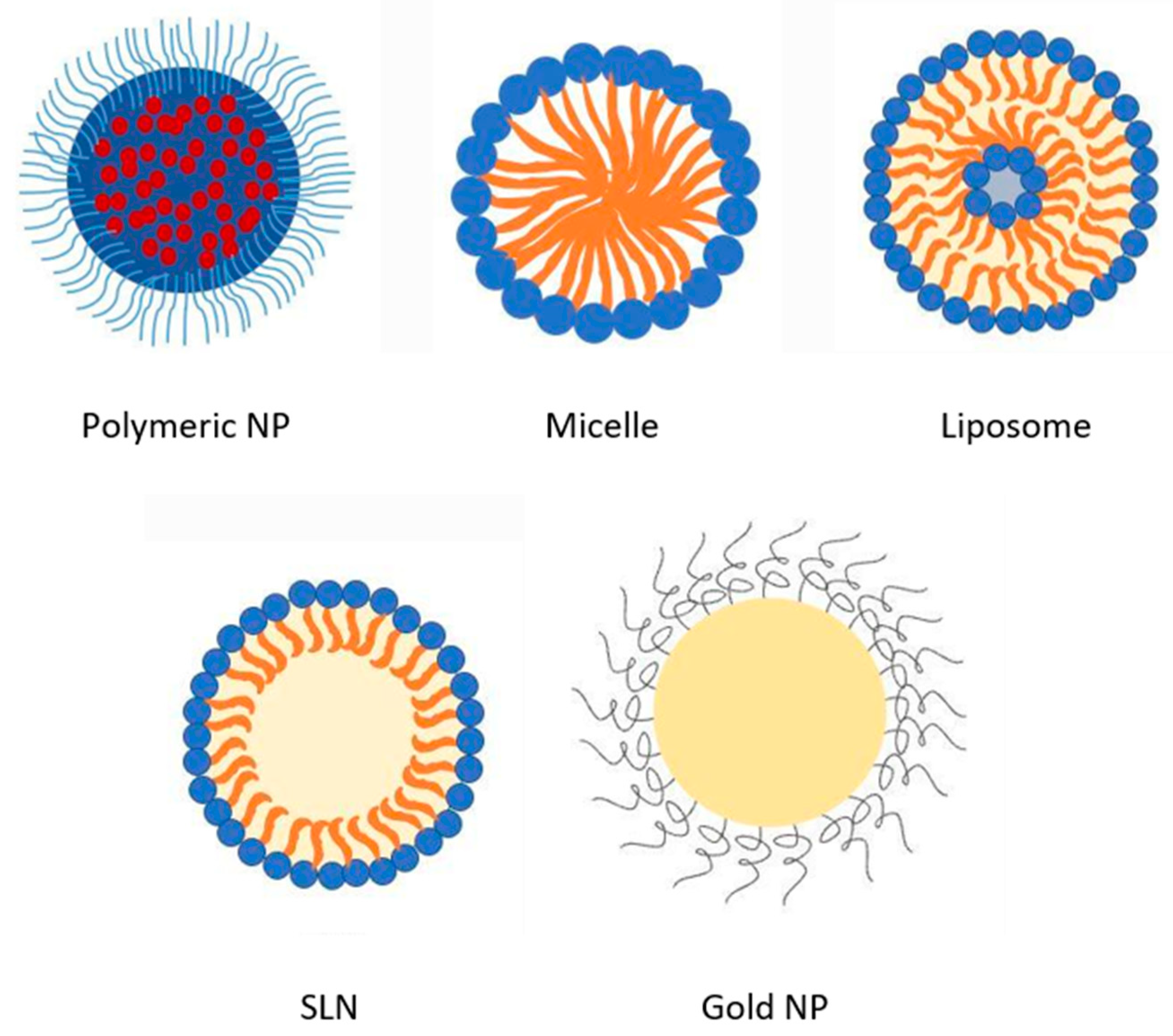

2. Overview of AmpB Nanoformulations

3. Factors Affecting Bioavailability of Orally Administered AmpB Nanoformulations

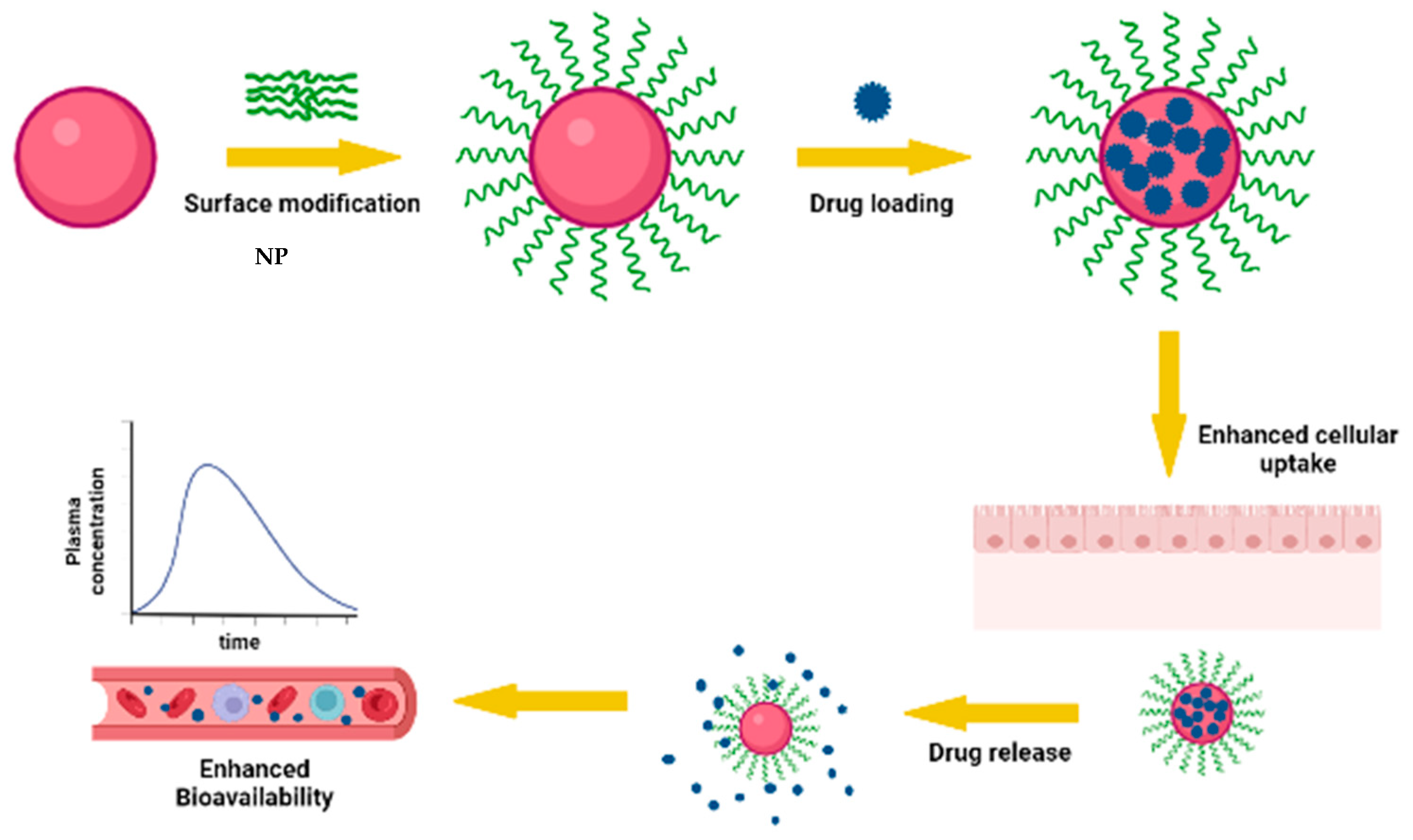

3.1. Impact of Nanoencapsulation of AmpB on Oral Bioavailability of AmpB

3.2. Effect of Encapsulation Efficiency on Oral Bioavailability

3.3. Effect of Surface Modification of Nanoparticles on Oral Bioavailability

3.4. Effect of Stability of AmpB Offered by Nanoparticle in Gastrointestinal Fluids on Oral Bioavailability

4. Clinical Trials Involving Oral AmpB Nanoformulations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banshoya, K.; Kaneo, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Maeda, H. Development of an amphotericin B micellar formulation using cholesterol-conjugated styrene-maleic acid copolymer for enhancement of blood circulation and antifungal selectivity. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 589, 119813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiphine, M.; Letscher-Bru, V.; Herbrecht, R. Amphotericin B and its new formulations: Pharmacologic characteristics, clinical efficacy, and tolerability. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 1999, 1, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolon, M.; Serrano, D.R.; Lalatsa, A.; De Pablo, E.; Torrado, J.J.; Ballesteros, M.P.; Healy, A.M.; Vega, C.; Coronel, C.; Bolas-Fernandez, F. Engineering oral and parenteral amorphous amphotericin B formulations against experimental trypanosoma cruzi infections. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, D.R.; Lalatsa, A. Oral amphotericin B: The journey from bench to market. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2017, 42, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolard, J. How do the polyene macrolide antibiotics affect the cellular membrane properties? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1986, 864, 257–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Wasan, K.M.; Lopez-Berestein, G. Development of liposomal polyene antibiotics: An historical perspective. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 6, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.A.; Vazquez, J.A.; Steffan, P.E.; Sobel, J.D.; Akins, R.A. High-frequency, in vitro reversible switching of Candida lusitaniae clinical isolates from amphotericin B susceptibility to resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambor, W.P.; Steinberg, B.A.; Suydam, L.O. Amphotericins A and B: Two new antifungal antibiotics possessing high activity against deep-seated and superficial mycoses. Antibiot. Annu. 1955, 3, 574–578. [Google Scholar]

- Oura, M.; Sternberg, T.; Wright, E. A new antifungal antibiotic, amphotericin B. Antibiot. Annu. 1955, 3, 566–573. [Google Scholar]

- Utz, J.; Louria, D.; Feder, N.; Emmons, C.; McCullough, N. A Report of Clinical Studies on the Use of Amphotericin in Patients with Systemic Fungal Diseases; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, R.; Ta-Chen, W.; Chiou, W.L. Poor and unusually prolonged oral absorption of amphotericin B in rats. Pharm. Res. 1999, 16, 455. [Google Scholar]

- Adler-Moore, J.P.; Proffitt, R. Amphotericin B lipid preparations: What are the differences? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brogden, R.N.; Goa, K.L.; Coukell, A.J. Amphotericin-B Colloidal Dispersion. Drugs 1998, 56, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdichevski, R.H.; Luis, L.B.; Crestana, L.; Manfro, R.C. Amphotericin B-related nephrotoxicity in low-risk patients. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 10, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepser, M. The value of amphotericin B in the treatment of invasive fungal infections. J. Crit. Care 2011, 26, 225.e1–225.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saqib, M.; Ali Bhatti, A.S.; Ahmad, N.M.; Ahmed, N.; Shahnaz, G.; Lebaz, N.; Elaissari, A. Amphotericin b loaded polymeric nanoparticles for treatment of leishmania infections. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golenser, J.; Domb, A. New formulations and derivatives of amphotericin B for treatment of leishmaniasis. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2006, 6, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, O.; Olbrich, C.; Yardley, V.; Kiderlen, A.; Croft, S. Formulation of amphotericin B as nanosuspension for oral administration. Int. J. Pharm. 2003, 254, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarji, B.; Raghuwanshi, D.; Vyas, S.; Kanaujia, P. Lipid nano spheres (LNSs) for enhanced oral bioavailability of amphotericin B: Development and characterization. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2007, 3, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, R.; Paderu, P.; Delmas, G.; Chen, Z.-W.; Mannino, R.; Zarif, L.; Perlin, D.S. Efficacy of oral cochleate-amphotericin B in a mouse model of systemic candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2356–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, K.; Nagpal, K.; Bera, T. Significance of algal polymer in designing amphotericin B nanoparticles. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 564573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano, R.G.d.J.V.; Tominaga, T.T.; Khalil, N.M.; Pedroso, L.S.; Mainardes, R.M. Chitosan functionalized poly (ε-caprolactone) nanoparticles for amphotericin B delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 202, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radwan, M.A.; AlQuadeib, B.T.; Šiller, L.; Wright, M.C.; Horrocks, B. Oral administration of amphotericin B nanoparticles: Antifungal activity, bioavailability and toxicity in rats. Drug Deliv. 2017, 24, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaioncz, S.; Khalil, M.N.; Mainardes, M.R. Exploring the role of nanoparticles in amphotericin B delivery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Li, Z. A review of drug release mechanisms from nanocarrier systems. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 76, 1440–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandermeulen, G.; Rouxhet, L.; Arien, A.; Brewster, M.; Préat, V. Encapsulation of amphotericin B in poly (ethylene glycol)-block-poly (ɛ-caprolactone-co-trimethylenecarbonate) polymeric micelles. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 309, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, C.D. Amphotericin B; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, Z.P. Types of nanomaterials and corresponding methods of synthesis. Nanomater. Med. Appl. 2013, 33–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, N.R.; Bicanic, T.; Salim, R.; Hope, W. Liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome®): A review of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, clinical experience and future directions. Drugs 2016, 76, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.A.; Patravale, V.B. AmbiOnp: Solid lipid nanoparticles of amphotericin B for oral administration. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2011, 7, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Wei, Y.; Syed, F.; Tahir, K.; Taj, R.; Khan, A.U.; Hameed, M.U.; Yuan, Q. Amphotericin B-conjugated biogenic silver nanoparticles as an innovative strategy for fungal infections. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 99, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Shivam, P.; Mandal, S.; Prasanna, P.; Kumar, S.; Prasad, S.R.; Kumar, A.; Das, P.; Ali, V.; Singh, S.K. Synthesis, characterization, and mechanistic studies of a gold nanoparticle–amphotericin B covalent conjugate with enhanced antileishmanial efficacy and reduced cytotoxicity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaydhane, M.; Choubey, P.; Sharma, C.S.; Majumdar, S. Gelatin nanofiber assisted zero order release of Amphotericin-B: A study with realistic drug loading for oral formulation. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 24, 100953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Valvi, P.U.; Swarnakar, N.K.; Thanki, K. Gelatin coated hybrid lipid nanoparticles for oral delivery of amphotericin B. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 2542–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Ven, H.; Paulussen, C.; Feijens, P.; Matheeussen, A.; Rombaut, P.; Kayaert, P.; Van den Mooter, G.; Weyenberg, W.; Cos, P.; Maes, L. PLGA nanoparticles and nanosuspensions with amphotericin B: Potent in vitro and in vivo alternatives to Fungizone and AmBisome. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, H.S.; Sohail, M.F.; Saljoughian, N.; Rehman, A.U.; Akhtar, S.; Nadhman, A.; Yasinzai, M.; Gendelman, H.E.; Satoskar, A.R.; Shahnaz, G. Design of mannosylated oral amphotericin B nanoformulation: Efficacy and safety in visceral leishmaniasis. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skiba-Lahiani, M.; Hallouard, F.; Mehenni, L.; Fessi, H.; Skiba, M. Development and characterization of oral liposomes of vegetal ceramide based amphotericin B having enhanced dry solubility and solubility. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 48, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, M.; Yang, M.; Chen, J.; Fang, W.; Xu, P. Evaluating the potential of cubosomal nanoparticles for oral delivery of amphotericin B in treating fungal infection. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, J.T.S.; Roberts, C.J.; Billa, N. Antifungal and mucoadhesive properties of an orally administered chitosan-coated amphotericin B nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC). AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quadeib, B.T.; Radwan, M.A.; Siller, L.; Horrocks, B.; Wright, M.C. Stealth Amphotericin B nanoparticles for oral drug delivery: In vitro optimization. Saudi Pharm. J. 2015, 23, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, S.; Gupta, P.K.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Dube, A.; Chourasia, M.K. Overexpressed macrophage mannose receptor targeted nanocapsules-mediated cargo delivery approach for eradication of resident parasite: In vitro and in vivo studies. Pharm. Res. 2015, 32, 2663–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Verma, A.; Dwivedi, P.; Dube, A.; Mishra, P.R. Covalent functionalized self-assembled lipo-polymerosome bearing amphotericin B for better management of leishmaniasis and its toxicity evaluation. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipa-Castro, A.; Nicolas, V.; Angelova, A.; Mekhloufi, G.; Prost, B.; Chéron, M.; Faivre, V.; Barratt, G. Cochleate formulations of Amphotericin b designed for oral administration using a naturally occurring phospholipid. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 603, 120688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasan, E.K.; Bartlett, K.; Gershkovich, P.; Sivak, O.; Banno, B.; Wong, Z.; Gagnon, J.; Gates, B.; Leon, C.G.; Wasan, K.M. Development and characterization of oral lipid-based amphotericin B formulations with enhanced drug solubility, stability and antifungal activity in rats infected with Aspergillus fumigatus or Candida albicans. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 372, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimtrakul, P.; Williams, D.B.; Tiyaboonchai, W.; Prestidge, C.A. Copolymeric micelles overcome the oral delivery challenges of amphotericin B. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, R.O.; de Lima, T.H.; Oréfice, R.L.; de Freitas Araújo, M.G.; de Lima Moura, S.A.; Magalhães, J.T.; da Silva, G.R. Amphotericin B-loaded poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanofibers: An alternative therapy scheme for local treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 107, 2674–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-García, R.; de Pablo, E.; Ballesteros, M.P.; Serrano, D.R. Unmet clinical needs in the treatment of systemic fungal infections: The role of amphotericin B and drug targeting. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 525, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Sime, F.B.; Cabot, P.J.; Maqbool, F.; Roberts, J.A.; Falconer, J.R. Solid nanoparticles for oral antimicrobial drug delivery: A review. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, H.; Xu, C.; Gu, L. A review: Using nanoparticles to enhance absorption and bioavailability of phenolic phytochemicals. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.; Raghuvanshi, S. Oral bioavailability: Issues and solutions via nanoformulations. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2015, 54, 325–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Yadav, P.; Swami, R.; Swarnakar, N.K.; Kushwah, V.; Katiyar, S.S. Lyotropic liquid crystalline nanoparticles of amphotericin B: Implication of phytantriol and glyceryl monooleate on bioavailability enhancement. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018, 19, 1699–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italia, J.; Yahya, M.; Singh, D.; Kumar, R.M. Biodegradable nanoparticles improve oral bioavailability of amphotericin B and show reduced nephrotoxicity compared to intravenous Fungizone®. Pharm. Res. 2009, 26, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Kumar, P.; Kush, P. Amphotericin B loaded ethyl cellulose nanoparticles with magnified oral bioavailability for safe and effective treatment of fungal infection. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 128, 110297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, S.G.M.; Ming, L.C.; Lee, K.S.; Yuen, K.H. Influence of the encapsulation efficiency and size of liposome on the oral bioavailability of griseofulvin-loaded liposomes. Pharmaceutics 2016, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.W.; Billa, N. Lipid effects on expulsion rate of amphotericin B from solid lipid nanoparticles. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, S.; Yadagiri, G.; Singh, A.; Karole, A.; Singh, O.P.; Sundar, S.; Mudavath, S.L. Improvising anti-leishmanial activity of amphotericin B and paromomycin using co-delivery in d-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) tailored nano-lipid carrier system. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2020, 231, 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Chen, M.; Yang, Z. Design of amphotericin B oral formulation for antifungal therapy. Drug Deliv. 2017, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Yadagiri, G.; Parvez, S.; Singh, O.P.; Verma, A.; Sundar, S.; Mudavath, S.L. Formulation, characterization and in vitro anti-leishmanial evaluation of amphotericin B loaded solid lipid nanoparticles coated with vitamin B12-stearic acid conjugate. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 117, 111279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabri, T.; Imran, M.; Rao, K.; Ali, I.; Arfan, M.; Shah, M.R. Fabrication of lecithin-gum tragacanth muco-adhesive hybrid nano-carrier system for in-vivo performance of Amphotericin B. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 194, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, L.; Karthik, R.; Srivastava, V.; Singh, S.P.; Pant, A.; Goyal, N.; Gupta, K.C. Efficient antileishmanial activity of amphotericin B and piperine entrapped in enteric coated guar gum nanoparticles. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 11, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederdorf, F.; Breithaupt, I.; Mannino, R.; Blum, D. Oral Administration of Amphotericin B (CAmB) in Humans: A Phase I Study of Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics; Scientific Presentations & Publications Matinas Biopharma: Bedminster, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Skipper, C.P.; Atukunda, M.; Stadelman, A.; Engen, N.W.; Bangdiwala, A.S.; Hullsiek, K.H.; Abassi, M.; Rhein, J.; Nicol, M.R.; Laker, E. Phase I EnACT trial of the safety and tolerability of a novel oral formulation of amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00838-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EnACT Trial of MAT2203 (Oral Amphotericin B) for the Treatment of Cryptococcal Meningitis; Scientific Presentations & Publications Matinas Biopharma: Bedminster, NJ, USA, 2021.

- Clinical Trials. 2018. Safety and Efficacy of Oral Encochleated Amphotericin B (CAMB/MAT2203) in the Treatment of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT02971007 (accessed on 27 June 2022).

| Drug Delivery System | Method of Preparation, Major Components and Key Features | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticles Nanosuspensions | Nanoprecipitation: PLGA, poloxamer 188 and 388. Size: 86–153 nm; ZP −31.0 mV. Solvent-antisolvent precipitation: PVA, DMSO. Size: 118–400 nm; ZP −20 mV. | AMP-B-loaded NP showed 2-fold and AmpB nanosuspensions showed 4-fold enhancement in antifungal activity compared to AmBisome® in a mouse model. | [35] |

| Mannose anchored thiomer nanocarriers | Covalent linkage of thioglycolic-chitosan followed by mannose addition: Mannose, chitosan. Size: 430–482 nm | 6-fold increase in oral BA and 3-fold increase in half-life with significantly less toxicity than the AmpB control. | [36] |

| Liposomes | Modified injection method: Egg yolk phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, ceramides. Size: 200 nm, EE > 75% | In an in vitro stomach–duodenum model, ceramides offered better membrane stability to ceramics anchored liposomes. Moreover, ceramides inhibited the detergent effect of bile salts on liposome membranes. | [37] |

| Cubosomes | High-pressure homogenization: Glyceryl monoolein, poloxamer 407. Size: 192 nm, EE > 94% | AmpB-loaded glyceryl monoolein cubosomes showed enhanced therapeutic efficacy than Fungizone®. A two-day treatment of 10 mg/kg dose was sufficient to attain therapeutic concentrations at the renal tissues for fungal treatment. | [38] |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) | Nanoprecipitation followed by probe sonication: Glyceride dilaurate, phosphatidylcholine, PEG-660–12 hydroxystearate. Size: 200 nm, EE > 95% | In vivo pharmacokinetics evaluation on Wistar rats showed faster onset of action and prolonged half-life than pure drug solution. | [30] |

| Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) | Homogenization ultrasonication: Chitosan, beeswax, coconut oil. Size: 394 nm, EE > 86% | NLC formulation showed comparable antifungal (in vitro) efficacy than AmpB and is twice less toxic to RBCs. | [39] |

| Stealth nanoparticles | Emulsification diffusion: PLGA-PEG copolymers, PVA, vitamin E, pluronic F68. Size: <1000 nm, EE > 56% | PEG concentration plays a significant role in size, EE, and drug release. 15% PEG demonstrated a controlled drug release of 54% up to 24 h. | [40] |

| Nanocapsules | Nanoemulsion production by emulsion solvent evaporation followed by chitosan deposition. Mannose sugar, chitosan, soya lecithin, polysorbate 80. Size:198 nm; ZP +31 mV, EE 96%. | Increased macrophage selectivity by interacting with overexpressed mannose receptors, resulting in 90% reduction in spleen parasite load and decreased nephrotoxicity. | [41] |

| Lipopolymerosome | Single-step nanoprecipitation: Glycol–chitosan, stearic acid, soya lecithin, cholesterol. Size: 243 nm; ZP +27 mV. | In vitro and in vivo evaluation demonstrated improved plasma drug stability and reduced toxicity compared to AmBisome® and Fungizone®. Enhanced anti-leishmanial activities and the glycol–chitosan copolymer was vital in improving the drug stability. | [42] |

| Polymer–lipid hybrid nanoparticles (PLN) | Desolvation method: Gelatin, lecithin, acetone, DMSO. Size: 253 nm, EE > 50.0% | Drug release followed Huguchi kinetics. Moreover, a 6-fold increase in intestinal permeability on Caco-2 cell lines and a 5-fold enhancement in oral BA was found compared to free AmpB. | [34] |

| Nanocochleates | Film hydration: Phosphatidylserine, lecithin, cholesterol, vitamin E. ZP −9 to −16 mV, EE > 50.0%. | Enhanced gastric stability and slow release in the GI medium. A confocal microscopy study demonstrated the integration of phosphatidylserine to the Caco-2 intestinal cell layers and slow drug release. | [43] |

| Self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) | Solvent evaporation: Glyceryl mono-oleate, PEG, phospholipids. Size: 200–400 nm, enhanced solubility stability in SGF or SIF | SEDDS significantly decreased fungal CFU in Sprague–Dawley rats infected with A. fumigatus and Candida albicans without causing renal toxicities. | [44] |

| Polymeric micelles | Solvent-diffusion and microfluidics technique: Copolymer Soluplus® (Polyvinyl caprolactam–PVA–PEG), VitE-TPGS Size: 80 nm, EE 95.0% | Enhanced cell uptake (6-fold) and permeability (2-fold) in Caco-2 cells in vitro while being less toxic than free AmpB. | [45] |

| Nanofibers | Electrospinning technique. PLGA, chloroform, 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol. Size: 582 nm, controlled delivery of AmpB for 8 days. | For vulvovaginal candidiasis, the vaginal fungal load in a murine model was eliminated after three days of local treatment. | [46] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fairuz, S.; Nair, R.S.; Billa, N. Orally Administered Amphotericin B Nanoformulations: Physical Properties of Nanoparticle Carriers on Bioavailability and Clinical Relevance. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1823. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14091823

Fairuz S, Nair RS, Billa N. Orally Administered Amphotericin B Nanoformulations: Physical Properties of Nanoparticle Carriers on Bioavailability and Clinical Relevance. Pharmaceutics. 2022; 14(9):1823. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14091823

Chicago/Turabian StyleFairuz, Shadreen, Rajesh Sreedharan Nair, and Nashiru Billa. 2022. "Orally Administered Amphotericin B Nanoformulations: Physical Properties of Nanoparticle Carriers on Bioavailability and Clinical Relevance" Pharmaceutics 14, no. 9: 1823. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14091823

APA StyleFairuz, S., Nair, R. S., & Billa, N. (2022). Orally Administered Amphotericin B Nanoformulations: Physical Properties of Nanoparticle Carriers on Bioavailability and Clinical Relevance. Pharmaceutics, 14(9), 1823. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14091823