Recent Research in Ocular Cystinosis: Drug Delivery Systems, Cysteamine Detection Methods and Future Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Drug Delivery Systems (DDSs)

2.1. Hydrogels

2.1.1. Synthetic Hydrogels

2.1.2. Natural Hydrogels

2.2. Nanowafers

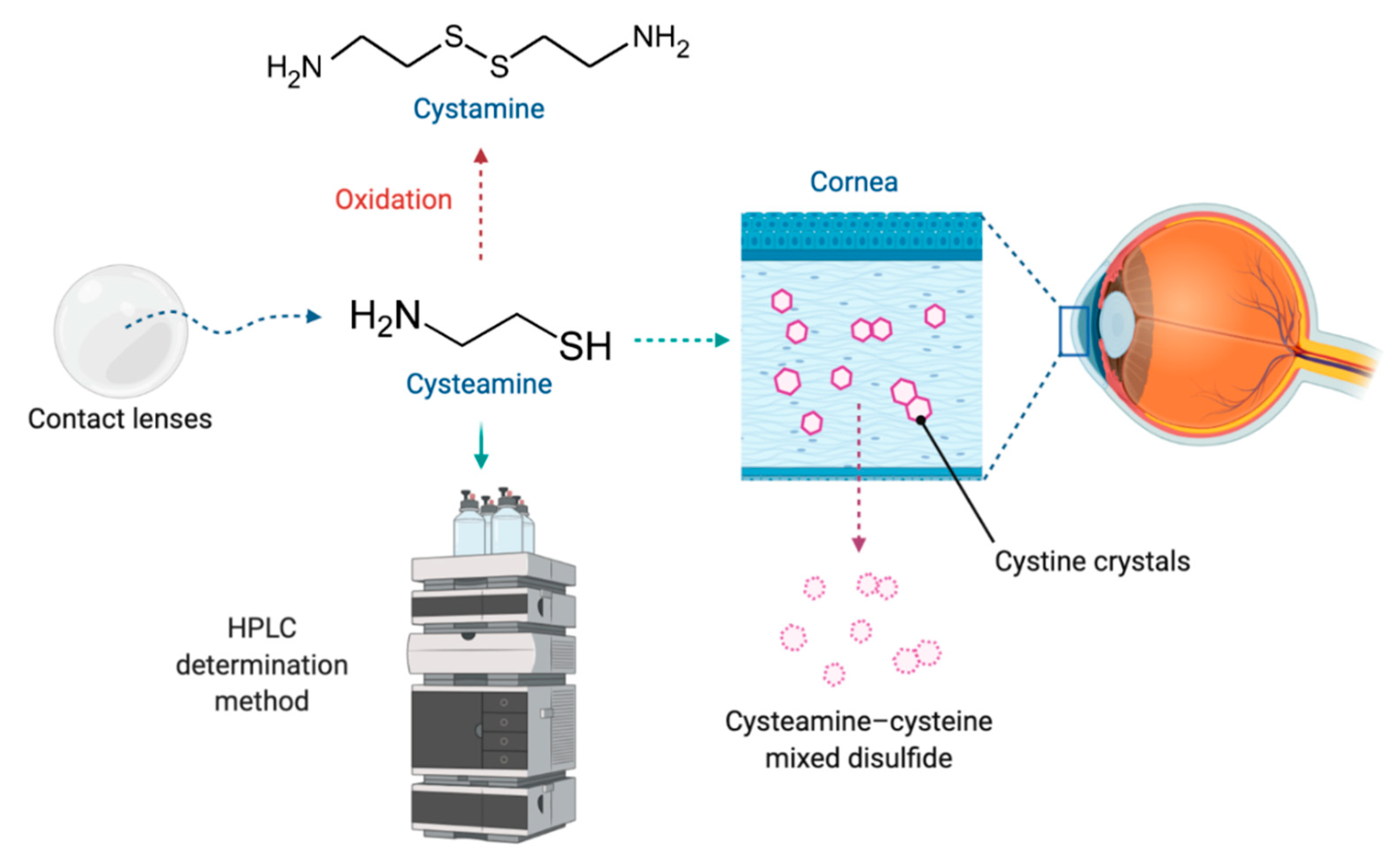

2.3. Contact Lenses

2.3.1. Contact Lenses as Drug Delivery Systems

2.3.2. Modified Contact Lenses

3. Stability and Analytical Determination Methods

3.1. Cysteamine Structure and Stability Properties

3.2. Cysteamine Analytical Determination Methods

3.2.1. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

3.2.2. Ion-Exchange Column Chromatography

3.2.3. Enzymatic Essay

3.2.4. Gas Chromatography

3.2.5. Electrochemical Detection

4. Current Situation and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, H.; Labbé, A.; Baudouin, C.; Plisson, C.; Giordano, V. Long-term follow-up of cystinosis patients treated with 0.55% cysteamine hydrochloride. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, F.; Livingstone, I.; Oladiwura, D.; Ramaesh, K. Treatment of corneal cystine crystal accumulation in patients with cystinosis. Clin. Ophthalmol. Auckl. NZ 2014, 8, 2077–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biswas, S.; Gaviria, M.; Malheiro, L.; Marques, J.P.; Giordano, V.; Liang, H. Latest Clinical Approaches in the Ocular Management of Cystinosis: A Review of Current Practice and Opinion from the Ophthalmology Cystinosis Forum. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2018, 7, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Syres, K.; Harrison, F.; Tadlock, M.; Jester, J.V.; Simpson, J.; Roy, S.; Salomon, D.R.; Cherqui, S. Successful treatment of the murine model of cystinosis using bone marrow cell transplantation. Blood 2009, 114, 2542–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buchan, B.; Kay, G.; Heneghan, A.; Matthews, K.H.; Cairns, D. Gel formulations for treatment of the ophthalmic complications in cystinosis. Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 392, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsuhaibani, A.H.; Khan, A.O.; Wagoner, M.D. Confocal microscopy of the cornea in nephropathic cystinosis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 89, 1530–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dixon, P.; Christopher, K.; Chauhan, A. Potential role of stromal collagen in cystine crystallization in cystinosis patients. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 551, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesterova, G.; Gahl, W.A. Cystinosis: The evolution of a treatable disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. Berl. Ger. 2013, 28, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luaces-Rodríguez, A.; Díaz-Tomé, V.; González-Barcia, M.; Silva-Rodríguez, J.; Herranz, M.; Gil-Martínez, M.; Rodríguez-Ares, M.T.; García-Mazás, C.; Blanco-Mendez, J.; Lamas, M.J.; et al. Cysteamine polysaccharide hydrogels: Study of extended ocular delivery and biopermanence time by PET imaging. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 528, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, B.; Kay, G.; Matthews, K.H.; Knott, R.; Cairns, D. Preformulation of cysteamine gels for treatment of the ophthalmic complications in cystinosis. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 515, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gahl, W.A.; Kuehl, E.M.; Iwata, F.; Lindblad, A.; Kaiser-Kupfer, M.I. Corneal Crystals in Nephropathic Cystinosis: Natural History and Treatment with Cysteamine Eyedrops. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000, 71, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Csorba, A.; Maka, E.; Maneschg, O.A.; Szabó, A.; Szentmáry, N.; Csidey, M.; Resch, M.; Imre, L.; Knézy, K.; Nagy, Z.Z. Examination of corneal deposits in nephropathic cystinosis using in vivo confocal microscopy and anterior segment optical coherence tomography: An age-dependent cross sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, M.; Toro, M.D.; Rejdak, R.; Załuska, W.; Gagliano, C.; Sikora, P. Ophthalmic Evaluation of Diagnosed Cases of Eye Cystinosis: A Tertiary Care Center’s Experience. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaughan, B.; Kay, G.; Knott, R.M.; Cairns, D. A potential new prodrug for the treatment of cystinosis: Design, synthesis and in-vitro evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 1716–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, Z.; Moloney, K.A.; Benylles, A.; Kay, G.; Knott, R.M.; Cairns, D. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of novel pro-drugs for the treatment of nephropathic cystinosis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 3492–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Sarma, P.; Kaur, H.; Prajapat, M.; Shekhar, N.; Bhattacharyya, J.; Kaur, H.; Kumar, S.; Medhi, B.; Ram, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of topical cysteamine in corneal cystinosis: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, R.L.; Thoene, J.G.; Christensen, H.N. Detection and characterization of carrier-mediated cationic amino acid transport in lysosomes of normal and cystinotic human fibroblasts. Role in therapeutic cystine removal? J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 4791–4798. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency. Cystagon®. Prescribing Information. 1997. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cystagon (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Schneider, J.A. Approval of cysteamine for patients with cystinosis. Pediatr. Nephrol. Berl. Ger. 1995, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Labbé, A.; Le Mouhaër, J.; Plisson, C.; Baudouin, C. A New Viscous Cysteamine Eye Drops Treatment for Ophthalmic Cystinosis: An Open-Label Randomized Comparative Phase III Pivotal Study. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Cystaran®. Prescribing Information. 2012. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/200740s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Food and Drug Administration. Cystadrops®. Prescribing Information. 2012. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/211302s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- European Medicines Agency. Cystadrops®. Prescribing Information. 2016. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/cystadrops-epar-product-information_es.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; Luaces-Rodríguez, A.; Díaz-Tomé, V.; Gil-Martínez, M.; Ares, M.T.R.; Peralba, R.T.; Blanco-Méndez, J.; González-Barcia, M.; Otero-Espinar, F.J.; Lamas, M.J. Cysteamine ophthalmic hydrogel for the treatment of ocular cystinosis. Farm. Hosp. 2017, 41, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, A.; Van Schepdael, A.; Adams, E.; Paul, P.; Devolder, D.; Elmonem, M.A.; Veys, K.; Casteels, I.; van den Heuvel, L.; Levtchenko, E. Effect of Storage Conditions on Stability of Ophthalmological Compounded Cysteamine Eye Drops. JIMD Rep. 2017, 42, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcano, D.C.; Shin, C.S.; Lee, B.; Isenhart, L.C.; Liu, X.; Li, F.; Jester, J.V.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Simpson, J.; Acharya, G. Synergistic Cysteamine Delivery Nanowafer as an Efficacious Treatment Modality for Corneal Cystinosis. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 3468–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannermaa, E.; Vellonen, K.-S.; Urtti, A. Drug transport in corneal epithelium and blood-retina barrier: Emerging role of transporters in ocular pharmacokinetics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006, 58, 1136–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, H.; Amaral, M.H.; Lobão, P.; Lobo, J.M.S. In situ gelling systems: A strategy to improve the bioavailability of ophthalmic pharmaceutical formulations. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gote, V.; Sikder, S.; Sicotte, J.; Pal, D. Ocular Drug Delivery: Present Innovations and Future Challenges. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 370, 602–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M. Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luaces-Rodríguez, A.; Mondelo-García, C.; Zarra-Ferro, I.; González-Barcia, M.; Aguiar, P.; Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; Otero-Espinar, F.J. Intravitreal anti-VEGF drug delivery systems for age-related macular degeneration. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 573, 118767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-C.; Chaw, J.-R.; Chen, C.-F.; Liu, H.-W. Controlled release bevacizumab in thermoresponsive hydrogel found to inhibit angiogenesis. Biomed. Mater. Eng. 2014, 24, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozdag, S.; Gumus, K.; Gumus, O.; Unlu, N. Formulation and in vitro evaluation of cysteamine hydrochloride viscous solutions for the treatment of corneal cystinosis. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008, 70, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; González Barcia, M.; Gil-Martínez, M.; Vieites-Prado, A.; Lema, I.; Argibay, B.; Blanco Méndez, J.; Lamas, M.J.; Otero-Espinar, F.J. In vitro and in vivo ocular safety and eye surface permanence determination by direct and Magnetic Resonance Imaging of ion-sensitive hydrogels based on gellan gum and kappa-carrageenan. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. Off. J. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Pharm. Verfahrenstechnik EV 2015, 94, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.-W.; Xie, R.; Ju, X.-J.; Wang, W.; Chen, Q.; Chu, L.-Y. Nano-structured smart hydrogels with rapid response and high elasticity. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, P.; Narvekar, P.; Lalani, R.; Chougule, M.B.; Pathak, Y.; Sutariya, V. An in vitro Assessment of Thermo-Reversible Gel Formulation Containing Sunitinib Nanoparticles for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Marcano, D.C.; Shin, C.S.; Hua, X.; Isenhart, L.C.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Acharya, G. Ocular Drug Delivery Nanowafer with Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shokry, M.; Hathout, R.M.; Mansour, S. Exploring gelatin nanoparticles as novel nanocarriers for Timolol Maleate: Augmented in-vivo efficacy and safe histological profile. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 545, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holgado, M.A.; Anguiano-Domínguez, A.; Martín-Banderas, L. Contact lenses as drug-delivery systems: A promising therapeutic tool. Arch. Soc. Espanola Oftalmol. 2020, 95, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Millán, E.; Castro-Balado, A.; Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; Otero-Espinar, F.J. Contact Lenses as Drug Delivery Systems. In Recent Progress in Eye Research; Eye and Vision Research Developments; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 91–154. ISBN 978-1-5361-2761-4. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrave, C.S.A.; Fang, F. Contact Lens Materials: A Materials Science Perspective. Materials 2019, 12, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Novack, G.D.; Barnett, M. Ocular Drug Delivery Systems Using Contact Lenses. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 36, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Balado, A.; Mondelo-García, C.; Zarra-Ferro, I.; Fernández-Ferreiro, A. New ophthalmic drug delivery systems. Farm. Hosp. 2020, 44, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; Castro-Balado, A.; García Quintanilla, L.; Lamas, M.; Otero-Espinar, F.; Mendez, J.; Gómez-Ulla, F.; Gil-Martínez, M.; Tomé, V.; Luaces-Rodríguez, A.; et al. Formulación Magistral Oftálmica Antiinfecciosa; SEFH. Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria: Madrid, Spain, 2019; ISBN 978-84-09-10764-3. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.-C.; Kim, J.; Chauhan, A. Extended delivery of hydrophilic drugs from silicone-hydrogel contact lenses containing Vitamin E diffusion barriers. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4032–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.-C.; Chauhan, A. Extended cyclosporine delivery by silicone—Hydrogel contact lenses. J. Control. Release 2011, 154, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.-C.; Burke, M.T.; Chauhan, A. Transport of Topical Anesthetics in Vitamin E Loaded Silicone Hydrogel Contact Lenses. Langmuir 2012, 28, 1478–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.-C.; Ben-Shlomo, A.; Mackay, E.O.; Plummer, C.E.; Chauhan, A. Drug Delivery by Contact Lens in Spontaneously Glaucomatous Dogs. Curr. Eye Res. 2012, 37, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.-C.; Burke, M.T.; Carbia, B.E.; Plummer, C.; Chauhan, A. Extended drug delivery by contact lenses for glaucoma therapy. J. Control. Release 2012, 162, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, K.-H.; Fentzke, R.C.; Chauhan, A. Feasibility of corneal drug delivery of cysteamine using vitamin E modified silicone hydrogel contact lenses. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 85, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New 1-Day ACUVUE® TruEye® Brand Contact Lenses (narafilcon A) Now Available in U.S. Johnson & Johnson. Available online: https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/new-1-day-acuvue-trueye-brand-contact-lenses-narafilcon-a-now-available-in-us (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Dixon, P.; Fentzke, R.C.; Bhattacharya, A.; Konar, A.; Hazra, S.; Chauhan, A. In vitro drug release and in vivo safety of vitamin E and cysteamine loaded contact lenses. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 544, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dureau, P.; Broyer, M.; Dufier, J.-L. Evolution of ocular manifestations in nephropathic cystinosis: A long-term study of a population treated with cysteamine. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2003, 40, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, G.M.; Havelaar, A.C.; Verheijen, F.W. Lysosomal transport disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2000, 23, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahl, W.A. Cystinosis coming of age. Adv. Pediatr. 1986, 33, 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, P.; Chauhan, A. Carbon Black Tinted Contact Lenses for Reduction of Photophobia in Cystinosis Patients. Curr. Eye Res. 2019, 44, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besouw, M.; Masereeuw, R.; van den Heuvel, L.; Levtchenko, E. Cysteamine: An old drug with new potential. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem Cysteamine. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/6058 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Labbé, A.; Baudouin, C.; Deschênes, G.; Loirat, C.; Charbit, M.; Guest, G.; Niaudet, P. A new gel formulation of topical cysteamine for the treatment of corneal cystine crystals in cystinosis: The Cystadrops OCT-1 study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014, 111, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah, C.; Charcosset, C.; Greige-Gerges, H. Challenges for cysteamine stabilization, quantification, and biological effects improvement. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkiss, R. Stability of Cysteamine Hydrochloride in Solution. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 1977, 2, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodrick, A.; Broughton, H.M.; Oakley, R.M. The stability of an oral liquid formulation of cysteamine. J. Clin. Hosp. Pharm. 1981, 6, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, P.; Powell, K.; Chauhan, A. Novel approaches for improving stability of cysteamine formulations. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 549, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Na, D.H. Simultaneous Determination of Cysteamine and Cystamine in Cosmetics by Ion-Pairing Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 35, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellum, E.; Bacon, V.A.; Patton, W.; Pereira, W.; Halpern, B. Quantitative determination of biologically important thiols and disulfides by gas-liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1969, 31, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofberg, R.T. Gas Chromatographic Analysis of Aminothiol Radioprotective Compounds. Anal. Lett. 1971, 4, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, R.C.; Newton, G.L.; Dorian, R.; Kosower, E.M. Analysis of biological thiols: Quantitative determination of thiols at the picomole level based upon derivatization with monobromobimanes and separation by cation-exchange chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1981, 111, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, G.L.; Dorian, R.; Fahey, R.C. Analysis of biological thiols: Derivatization with monobromobimane and separation by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1981, 114, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.; Massoud, R.; Motti, C.; Lo Russo, A.; Fucci, G.; Cortese, C.; Federici, G. Fully automated assay for total homocysteine, cysteine, cysteinylglycine, glutathione, cysteamine, and 2-mercaptopropionylglycine in plasma and urine. Clin. Chem. 1998, 44, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachowicz, M.; Lehmann, B.; Tibi, A.; Prognon, P.; Daurat, V.; Pradeau, D. Determination of total cysteamine in human serum by a high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1998, 17, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyo’oka, T.; Imai, K. High-performance liquid chromatography and fluorometric detection of biologically important thiols, derivatized with ammonium 7-fluorobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole-4-sulphonate (SBD-F). J. Chromatogr. 1983, 282, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichinose, S.; Nakamura, M.; Maeda, M.; Ikeda, R.; Wada, M.; Nakazato, M.; Ohba, Y.; Takamura, N.; Maeda, T.; Aoyagi, K.; et al. A validated HPLC-fluorescence method with a semi-micro column for routine determination of homocysteine, cysteine and cysteamine, and the relation between the thiol derivatives in normal human plasma. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2009, 23, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, H.; Tanaka, H.; Makita, M. Determination of total cysteamine in urine and plasma samples by gas chromatography with flame photometric detection. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 1994, 657, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Ohkuma, S.; Kuriyama, K. Determination of cystamine by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1984, 136, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H.; Imamura, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Makita, M. Determination of cysteamine and cystamine by gas chromatography with flame photometric detection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1993, 11, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuśmierek, K.; Głowacki, R.; Bald, E. Determination of total cysteamine in human plasma in the form of its 2-S-quinolinium derivative by high performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005, 382, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogony, J.; Mare, S.; Wu, W.; Ercal, N. High performance liquid chromatography analysis of 2-mercaptoethylamine (cysteamine) in biological samples by derivatization with N-(1-pyrenyl) maleimide (NPM) using fluorescence detection. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life. Sci. 2006, 843, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, M.; Toriumi, C.; Santa, T.; Imai, K. Fluorogenic derivatization reagents suitable for isolation and identification of cysteine-containing proteins utilizing high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoto, H.; Ichibangase, T.; Saimaru, H.; Uchikura, K.; Imai, K. Existence of low-molecular-weight thiols in Caenorhabditis elegans demonstrated by HPLC-fluorescene detection utilizing 7-chloro-N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole-4-sulfonamide. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2007, 21, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, M.; Gibrat, C.; Ouellet, M.; Rouillard, C.; Calon, F.; Cicchetti, F. Cystamine metabolism and brain transport properties: Clinical implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neurochem. 2010, 114, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, B.D.; Tam, L.-T.T.; Lu, H.S.; Valladares, V.G. A fluorescent-based HPLC assay for quantification of cysteine and cysteamine adducts in Escherichia coli-derived proteins. J. Chromatogr. B 2012, 880, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, P.T.N.; Nguyen, P.H.; Nguyen, M.A. Determination of cysteamine in animal feeds by high performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection (HPLC-DAD). Sci. Technol. Dev. J. 2018, 21, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiung, M.; Yeo, Y.Y.; Itiaba, K.; Crawhall, J.C. Cysteamine, penicillamine, glutathione, and their derivatives analyzed by automated ion exchange column chromatography. Biochem. Med. 1978, 19, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Nardini, M.; Chiaraluce, R.; Duprè, S.; Cavallini, D. Detection and determination of cysteamine at the nanomole level. J. Appl. Biochem. 1983, 5, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duffel, M.W.; Logan, D.J.; Ziegler, D.M. Cysteamine and cystamine. Methods Enzymol. 1987, 143, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.J.; Perrett, D.; Rudge, S.R. The determination of cysteamine in physiological fluids by HPLC with electrochemical detection. Biomed. Chromatogr. 1987, 2, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolin, L.A.; Schneider, J.A. Measurement of total plasma cysteamine using high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Anal. Biochem. 1988, 168, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.A.G.; Hirschberger, L.L.; Stipanuk, M.H. Measurement of cyst(e)amine in physiological samples by high performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1988, 170, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, J.B.; Ojani, R.; Chekin, F. Fabrication of functionalized carbon nanotube modified glassy carbon electrode and its application for selective oxidation and voltammetric determination of cysteamine. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2009, 633, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojani, R.; Raoof, J.-B.; Zarei, E. Electrocatalytic Oxidation and Determination of Cysteamine by Poly-N,N-dimethylaniline/Ferrocyanide Film Modified Carbon Paste Electrode. Electroanalysis 2009, 21, 1189–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Maleh, H.; Biparva, P.; Hatami, M. A novel modified carbon paste electrode based on NiO/CNTs nanocomposite and (9, 10-dihydro-9, 10-ethanoanthracene-11, 12-dicarboximido)-4-ethylbenzene-1, 2-diol as a mediator for simultaneous determination of cysteamine, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and folic acid. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 48, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi-Maleh, H.; Salimi-Amiri, M.; Karimi, F.; Khalilzadeh, M.A.; Baghayeri, M. A Voltammetric Sensor Based on NiO Nanoparticle-Modified Carbon-Paste Electrode for Determination of Cysteamine in the Presence of High Concentration of Tryptophan. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jchem/2013/946230/ (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Salmanpour, S.; Abbasghorbani, M.; Karimi, F.; Bavandpour, R.; Wen, Y. Electrocatalytic Determination of Cysteamine Uses a Nanostructure Based Electrochemical Sensor in Pharmaceutical Samples. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2017, 13, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabali, V.; Karimi-Maleh, H. Electrochemical determination of cysteamine in the presence of guanine and adenine using a carbon paste electrode modified with N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3,5-dinitrobenzamide and magnesium oxide nanoparticles. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 5604–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Maleh, H.; Karimi, F.; Orooji, Y.; Mansouri, G.; Razmjou, A.; Aygun, A.; Sen, F. A new nickel-based co-crystal complex electrocatalyst amplified by NiO dope Pt nanostructure hybrid; a highly sensitive approach for determination of cysteamine in the presence of serotonin. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvanfard, M.; Ahmadi, M.; Karimi, F.; Alizad, K. Voltammetric determination of cysteamine at multiwalled carbon nanotubes paste electrode in the presence of isoproterenol as a mediator. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2014, 25, 1244–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, A.; Karimi-Maleh, H.; Ensafi, A.A.; Beitollahi, H.; Hosseini, A.; Khalilzadeh, M.A.; Bagheri, H. Simultaneous determination of cysteamine and folic acid in pharmaceutical and biological samples using modified multiwall carbon nanotube paste electrode. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2012, 23, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvanfard, M.; Sami, S.; Karimi-Maleh, H.; Alizad, K. Electrocatalytic determination of cysteamine using multiwall carbon nanotube paste electrode in the presence of 3,4-dihydroxycinnamic acid as a homogeneous mediator. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2013, 24, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rezaei, B.; Khosropour, H.; Ensafi, A.A. Sensitive voltammetric determination of cysteamine using promazine hydrochloride as a mediator and modified multi-wall carbon nanotubes carbon paste electrodes. Ionics 2014, 20, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.Z.; Tajik, S.; Beitollahi, H.; Barani, Z. Sensitive Cysteamine Determination Using Disposable Electrochemical Sensor Based on Modified Screen Printed Electrode. Biquarterly Iran. J. Anal. Chem. 2019, 6, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stem Cell Gene Therapy for Cystinosis—Full Text View—ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03897361 (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Makuloluwa, A.K.; Shams, F. Cysteamine hydrochloride eye drop solution for the treatment of corneal cystine crystal deposits in patients with cystinosis: An evidence-based review. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 12, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaiser-Kupfer, M.I.; Gazzo, M.A.; Datiles, M.B.; Caruso, R.C.; Kuehl, E.M.; Gahl, W.A. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of cysteamine eye drops in nephropathic cystinosis. Arch. Ophthalmol. Chic. Ill 1960 1990, 108, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, F.; Kuehl, E.M.; Reed, G.F.; McCain, L.M.; Gahl, W.A.; Kaiser-Kupfer, M.I. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Topical Cysteamine Disulfide (Cystamine) versus Free Thiol (Cysteamine) in the Treatment of Corneal Cystine Crystals in Cystinosis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 1998, 64, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradbury, J.A.; Danjoux, J.P.; Voller, J.; Spencer, M.; Brocklebank, T. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of topical cysteamine therapy in patients with nephropathic cystinosis. Eye Lond. Engl. 1991, 5, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsilou, E.T. A multicentre randomised double masked clinical trial of a new formulation of topical cysteamine for the treatment of corneal cystine crystals in cystinosis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varner, P. Ophthalmic pharmaceutical clinical trials: Design considerations. Clin. Investig. 2015, 5, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathout, R.M. Particulate Systems in the Enhancement of the Antiglaucomatous Drug Pharmacodynamics: A Meta-Analysis Study. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 21909–21913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrzejewska, Z.; Nevo, N.; Thomas, L.; Chhuon, C.; Bailleux, A.; Chauvet, V.; Courtoy, P.J.; Chol, M.; Guerrera, I.C.; Antignac, C. Cystinosin is a Component of the Vacuolar H+-ATPase-Ragulator-Rag Complex Controlling Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 Signaling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2016, 27, 1678–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thoene, J.G.; DelMonte, M.A.; Mullet, J. Microvesicle delivery of a lysosomal transport protein to ex vivo rabbit cornea. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2020, 23, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollywood, J.A.; Przepiorski, A.; D’Souza, R.F.; Sreebhavan, S.; Wolvetang, E.J.; Harrison, P.T.; Davidson, A.J.; Holm, T.M. Use of human induced pluripotent stem cells and kidney organoids to develop a cysteamine/mtor inhibition combination therapy for cystinosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 962–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Polymer Name | Polymer Type | % Released Cysteamine | Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbomer 934 | Synthetic | 80 | 210 min 1 | [5] |

| Hyaluronic acid | Natural | 60.7 | 24 h | [9] |

| 88% Deacylated gellan gum and 12% kappa carrageenan | Natural | 36.3 | 24 h | [9] |

| Carbomer 934 | Synthetic | 80 | 20 min | [10] |

| Hydroxyethyl cellulose | Natural | 80 | 14 min | [10] |

| Hyaluronic acid | Natural | 80 | 14 min | [10] |

| Hydroxypropylmethyl-cellulose | Natural | 81.2 | 8 h | [33] |

| Commercial Name | Material | Diffusion Barrier | Total Cysteamine Release Amount (μg) | Release Duration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-DAY ACUVUE® TruEye™ | Narafilcon B (silicone hydrogel) | 10.22% VE 1 | 600.1 ± 27.2 | 25 min | [50] |

| 1-DAY ACUVUE® TruEye™ | Narafilcon B (silicone hydrogel) | 22.24% VE | 527.7 ± 21.7 | 90 min | [50] |

| ACUVUE® OASYS® | Senofilcon A (silicone hydrogel) | 19.14% VE | 408.8 ± 33.9 | 3 h | [50] |

| 1-DAY ACUVUE® TruEye™ | Narafilcon A (silicone hydrogel) | 10% VE | 651 ± 31.2 | 0.90 h | [52] |

| 1-DAY ACUVUE® TruEye™ | Narafilcon A (silicone hydrogel) | 20% VE | 603.1 ± 21.2 | 2 h | [52] |

| 1-DAY ACUVUE® TruEye™ | Narafilcon A (silicone hydrogel) | 30% VE | 538.9 ± 17.3 | 4 h | [52] |

| ACUVUE® OASYS® | Senofilcon A (silicone hydrogel) | 10% VE | 464.0 ± 8.6 | 0.89 h | [52] |

| ACUVUE® OASYS® | Senofilcon A (silicone hydrogel) | 20% VE | 408.1 ± 36.7 | 2.15 | [52] |

| ACUVUE® OASYS® | Senofilcon A (silicone hydrogel) | 30% VE | 345.0 ± 33.2 | 4.25 h | [52] |

| Noncommercial | - | 0.3% CB 2 | 148 ± 10 | 10 min | [56] |

| Noncommercial | - | 0.3% CB + 20% VE | 123 ± 7 | 40 min | [56] |

| Derivatization Agent | Stationary Phase | Mobile Phase | Flow Rate (mL/min) | Detector 1 | T (°C) | Elution Time (min) | Limit of Detection | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-chloro-1-methylquinolinium tetrafluoroborate | C18 (5 μm; 4.6 mm × 150 mm) | Gradient elution or isocratic elution (trichloro acetic acid and acetonitrile) | 1 | UV | 25 | 9 | 0.1 μM | [76] |

| Monobromo-bimane | C18 (5 μm; 4.6 mm × 150 mm) | Gradient elution (methanol, acetic acid and water) | 1.5 | FL | RT | 12.5 | nmol | [68] |

| Monobromo-bimane | C18 (3 μm; 4.6 mm × 150 mm) | Acetonitrile | 1.5 | FL | RT | 4.3 | 50 nM | [69] |

| Monobromo-bimane | C18 (5 μm; 2.1 mm × 100 mm) | Water: methanol (65:35) | 0.3 | FL | - | 11 | 2 nM | [70] |

| Ammonium 7-fluorobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole-4-sulphonate | C18 (8–10 μm; 3.9 mm × 300 mm) | Gradient elution (methanol and sodium acetate) | 1 | FL | RT | 10 | 0.07 pmol | [71] |

| Ammonium 7-fluorobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole-4-sulphonate | C18 (5 μm; 2.0 mm × 250 mm) | Phosphate buffer: CH3CN (96:4) | 0.3 | FL | 30 | 5 | 0.47 μM | [72] |

| N-(1-pyrenyl) maleimide | C18 (5 μm; 4.6 mm × 250 mm) | Acetonitrile: water (70:30) | 1 | FL | RT | 10 | 0.01 nM | [77] |

| 7-chloro-N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]-2,1,3- benzoxadiazole-4-sulfonamide | C18 (2 nm, 4.6 mm × 150 mm) | Gradient elution (water, acetonitrile and trifluoroacetic acid) | 0.6 | FL | 50 | 6.4 | 154 fmol | [79] |

| 4-fluoro-7-sulfamoyl benzofurazan | C18 (3 μm; 3.9 mm × 150 mm) | 2.5% methanol and ammonium acetate | 1 | FL | - | - | - | [80] |

| 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate | C18 (5 μm; 2.1 mm × 150 mm) | Gradient elution (sodium acetate and trimethyl- amine, acetonitrile and water) | 0.3 | FL | RT | 29 | 0.77 pmol | [81] |

| - | C18 (5 μm; 4.6 mm × 250 mm) | NaHpSO in phosphoric acid:acetonitrile (85:15) | 1 | UV | 25 | 6.9 | 0.032 μg | [64] |

| 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic) acid | C18 (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm) | Gradient elution (formic acid and acetonitrile) | 1.0 | UV | RT | 26 | 3.3 mg | [82] |

| Derivatization Agent | Carrier Gas | Column Used | Temperature (°C) | Limit of Detection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pivaldehyde 1 | Helium (35 mL/min) | 5% SE-30 5′ × 1/8” | From 80° to 250 °C at 10°/min | 8 pmole | [65] |

| (Trimethylsilyl) trifluoro acetamide1 | Helium (80 mL/min) | 2% SE-30 6 ft. ¼ | From 75° to 230 °C at 8°/min | Sub nanomole | [66] |

| Isobutyl Chloroformate 2 | Nitrogen (8 mL/min) | DB-210 15 m × 0.53 mm | From 170° to 250 °C at 5°/min | 2 pmole | [73] |

| Isobutyl Chloroformate 2 | Nitrogen (10 mL/min) | DB-210 15 m × 0.53 mm | From 170° to 250 °C at 5°/min | 2 pmole | [75] |

| Electrode | Mediator | Concentrations Range (μM) | Limit of Detection (μM) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-wall carbon nanotube modified glassy carbon electrode | 1,2-N-aphthoquinone-4-sulfonic acid sodium | 5.0–270 | 3.0 | [89] |

| Carbon paste electrode | N,N-dimethylaniline/ferrocyanide | 80–1140 | 79.7 | [90] |

| Carbon paste electrode | (9, 10-dihydro-9, 10-ethanoanthracene-11, 12-dicarboximido)-4-Ethylbenzene-1, 2-diol and nickel-oxidecarbon nanotube | 0.01–250 | 0.007 | [91] |

| Carbon paste electrode | Ferrocene carboxaldehyde and nickel-oxide nanoparticle | 0.09–300 | 0.06 | [92] |

| Carbon paste electrode | Acetylferrocene and Nickel-oxide-carbon nanotube | 0.1–600 | 0.07 | [93] |

| Carbon paste electrode | N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3,5-Dinitrobenzamide and magnesium oxide nanoparticles | 0.03–600 | 0.009 | [94] |

| Carbon paste electrode | NiO dope Pt nanostructure hybrid (NiO–Pt–H) | 0.003–200 | 0,0005 | [95] |

| Multiwall carbon nanotubes paste electrode | Isoproterenol | 0.3–450.0 | 0.09 | [96] |

| Multiwall carbon nanotubes paste Electrode | Ferrocene | 0.7–200 | 0.3 | [97] |

| Multiwall carbon nanotubes paste electrode | 3,4-Dihydroxycinnamic acid | 0.25–400 | 0.09 | [98] |

| Multiwall carbon nanotubes paste electrode | Promazine hydrochloride | Two dynamic ranges of 2.0–346.5 μM and 346.5–1912.5 μM | 0.8 | [99] |

| Screen printed electrode | La2O3/Co3O4 | 1.0–700.0 | 0.3 | [100] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro-Balado, A.; Mondelo-García, C.; Varela-Rey, I.; Moreda-Vizcaíno, B.; Sierra-Sánchez, J.F.; Rodríguez-Ares, M.T.; Hermelo-Vidal, G.; Zarra-Ferro, I.; González-Barcia, M.; Yebra-Pimentel, E.; et al. Recent Research in Ocular Cystinosis: Drug Delivery Systems, Cysteamine Detection Methods and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12121177

Castro-Balado A, Mondelo-García C, Varela-Rey I, Moreda-Vizcaíno B, Sierra-Sánchez JF, Rodríguez-Ares MT, Hermelo-Vidal G, Zarra-Ferro I, González-Barcia M, Yebra-Pimentel E, et al. Recent Research in Ocular Cystinosis: Drug Delivery Systems, Cysteamine Detection Methods and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 2020; 12(12):1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12121177

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro-Balado, Ana, Cristina Mondelo-García, Iria Varela-Rey, Beatriz Moreda-Vizcaíno, Jesús F. Sierra-Sánchez, María Teresa Rodríguez-Ares, Gonzalo Hermelo-Vidal, Irene Zarra-Ferro, Miguel González-Barcia, Eva Yebra-Pimentel, and et al. 2020. "Recent Research in Ocular Cystinosis: Drug Delivery Systems, Cysteamine Detection Methods and Future Perspectives" Pharmaceutics 12, no. 12: 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12121177

APA StyleCastro-Balado, A., Mondelo-García, C., Varela-Rey, I., Moreda-Vizcaíno, B., Sierra-Sánchez, J. F., Rodríguez-Ares, M. T., Hermelo-Vidal, G., Zarra-Ferro, I., González-Barcia, M., Yebra-Pimentel, E., Giráldez-Fernández, M. J., Otero-Espinar, F. J., & Fernández-Ferreiro, A. (2020). Recent Research in Ocular Cystinosis: Drug Delivery Systems, Cysteamine Detection Methods and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics, 12(12), 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12121177