Microneedles Drug Delivery Systems for Treatment of Cancer: A Recent Update

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. General Characteristics of MNs

2.1. History

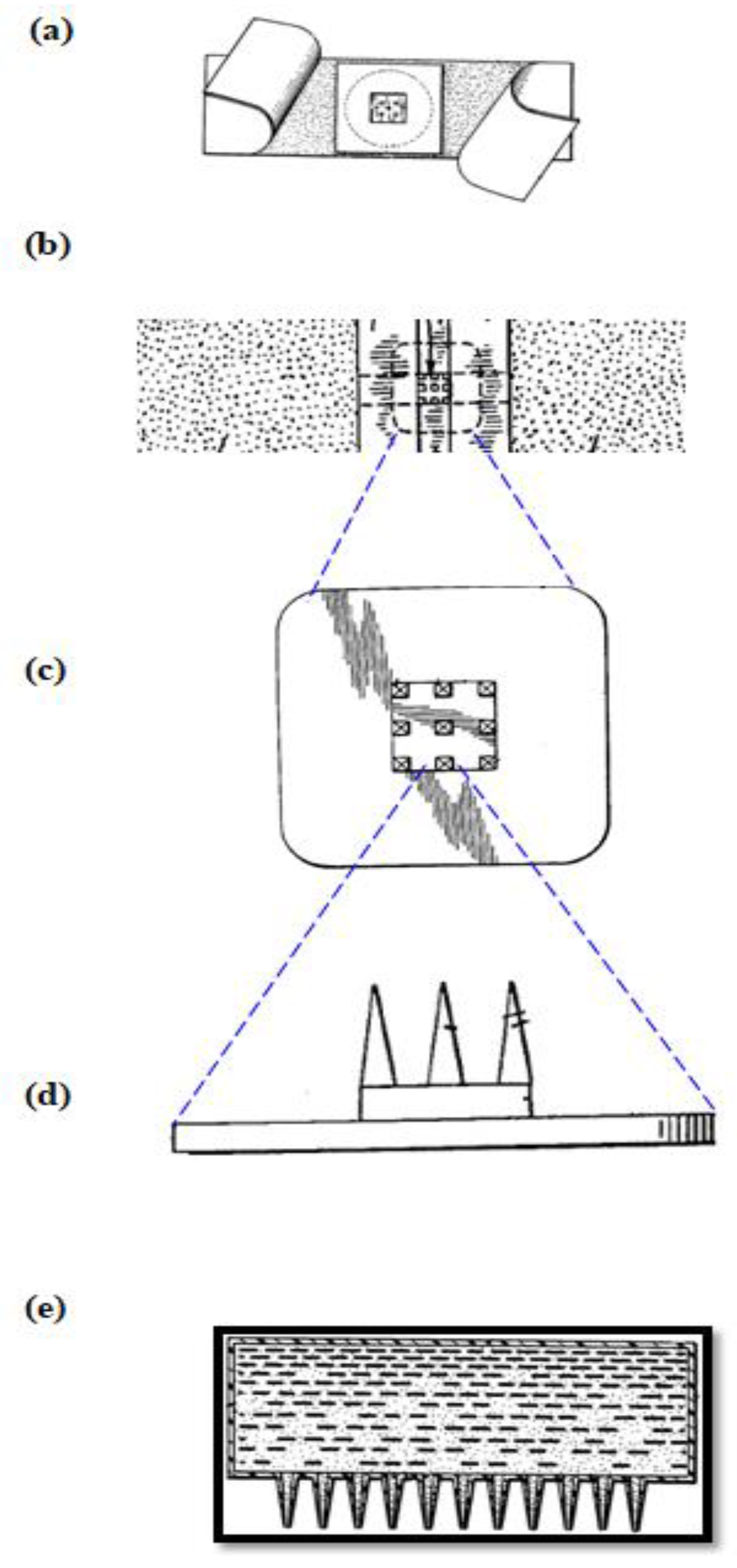

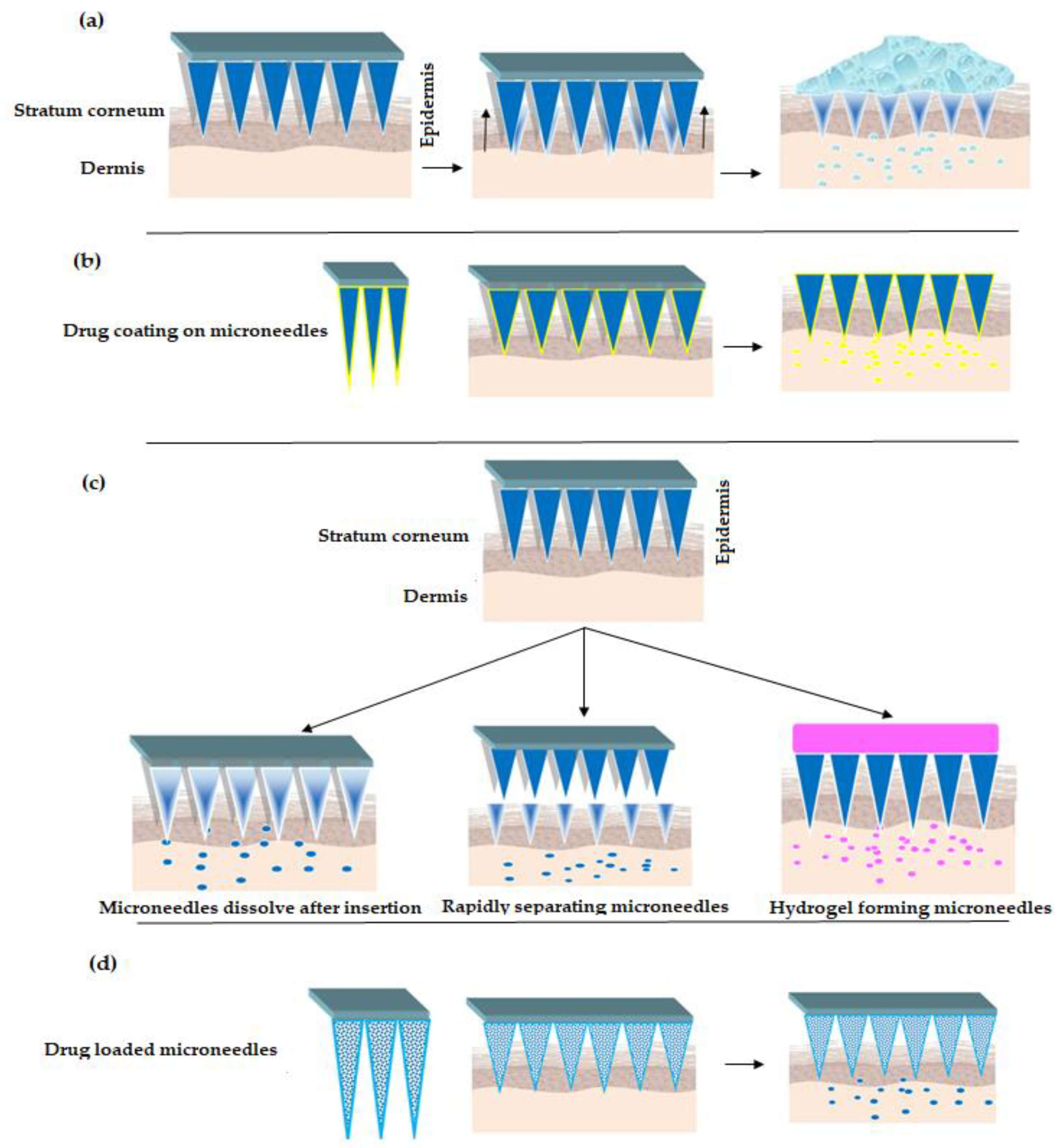

2.2. Approaches for Drug Delivery

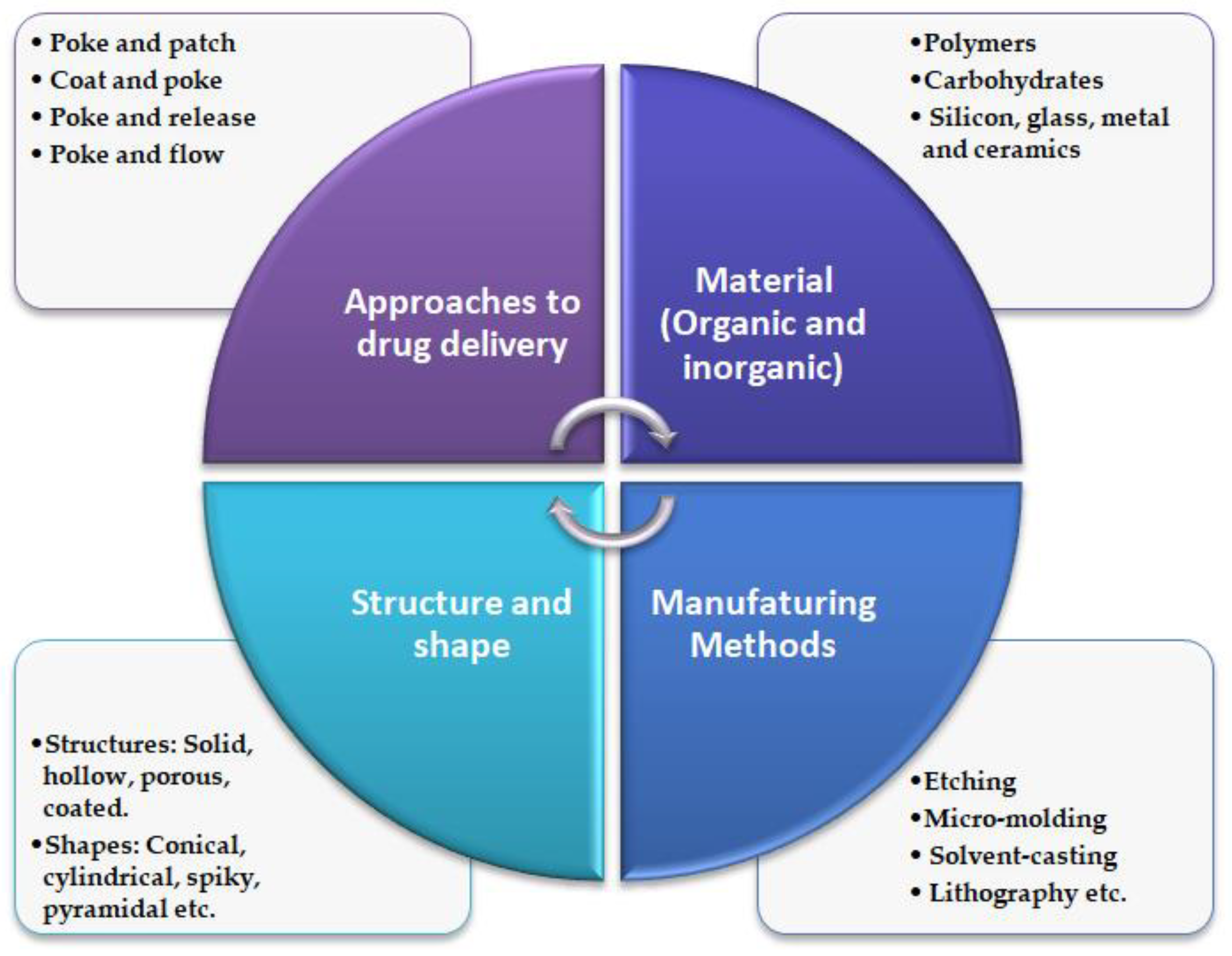

2.3. Manufacturing Methods and Materials

2.4. Clinical Applications

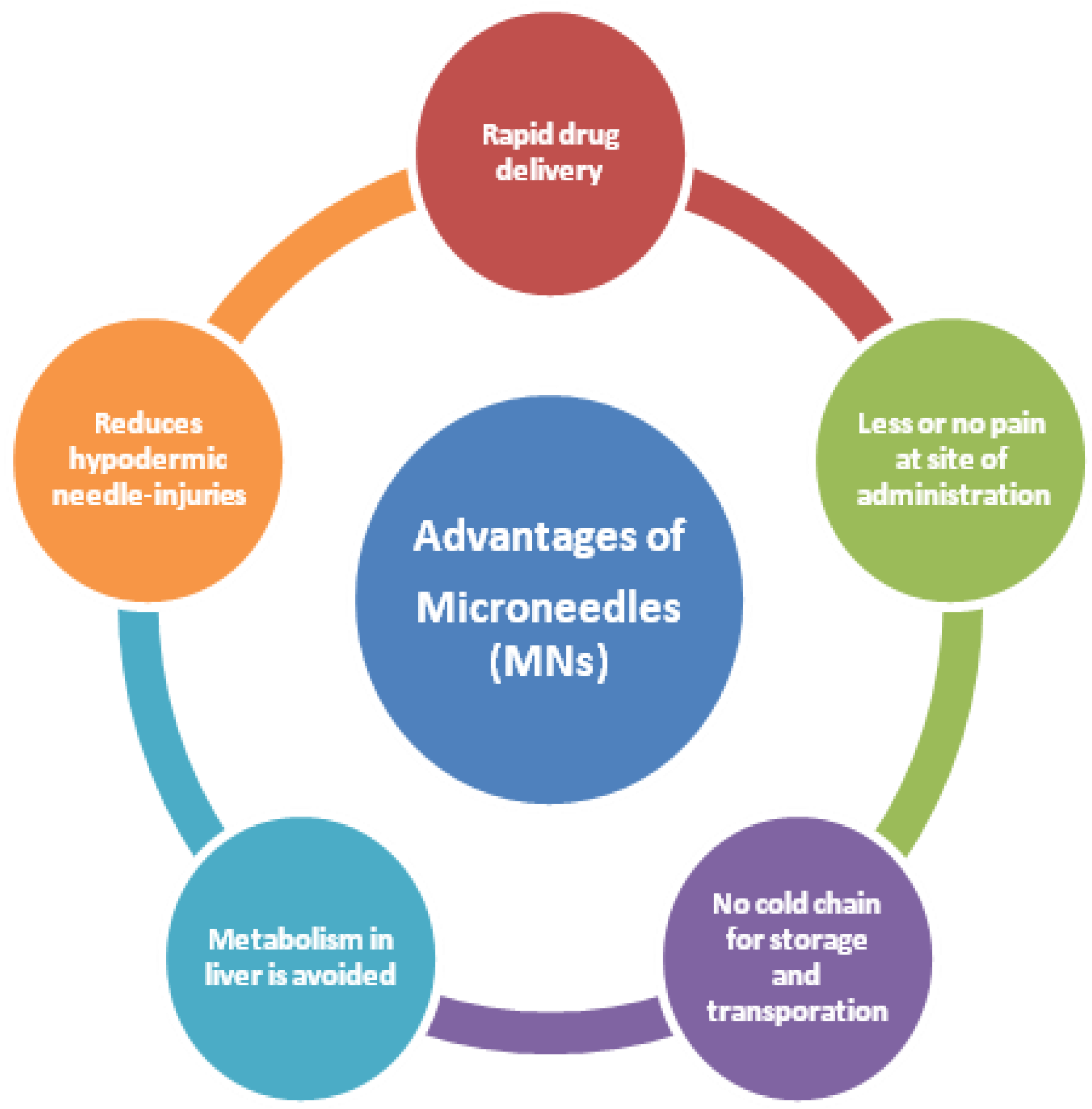

2.4.1. Clinical Benefits

2.4.2. Clinical Challenges

2.4.3. Clinical Applications with Improved Therapeutic Outcome

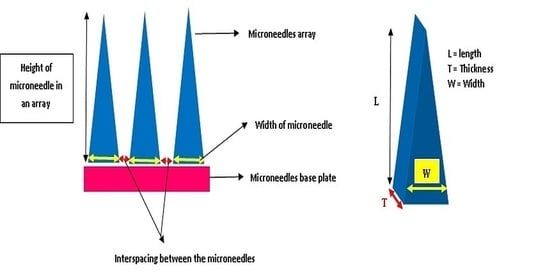

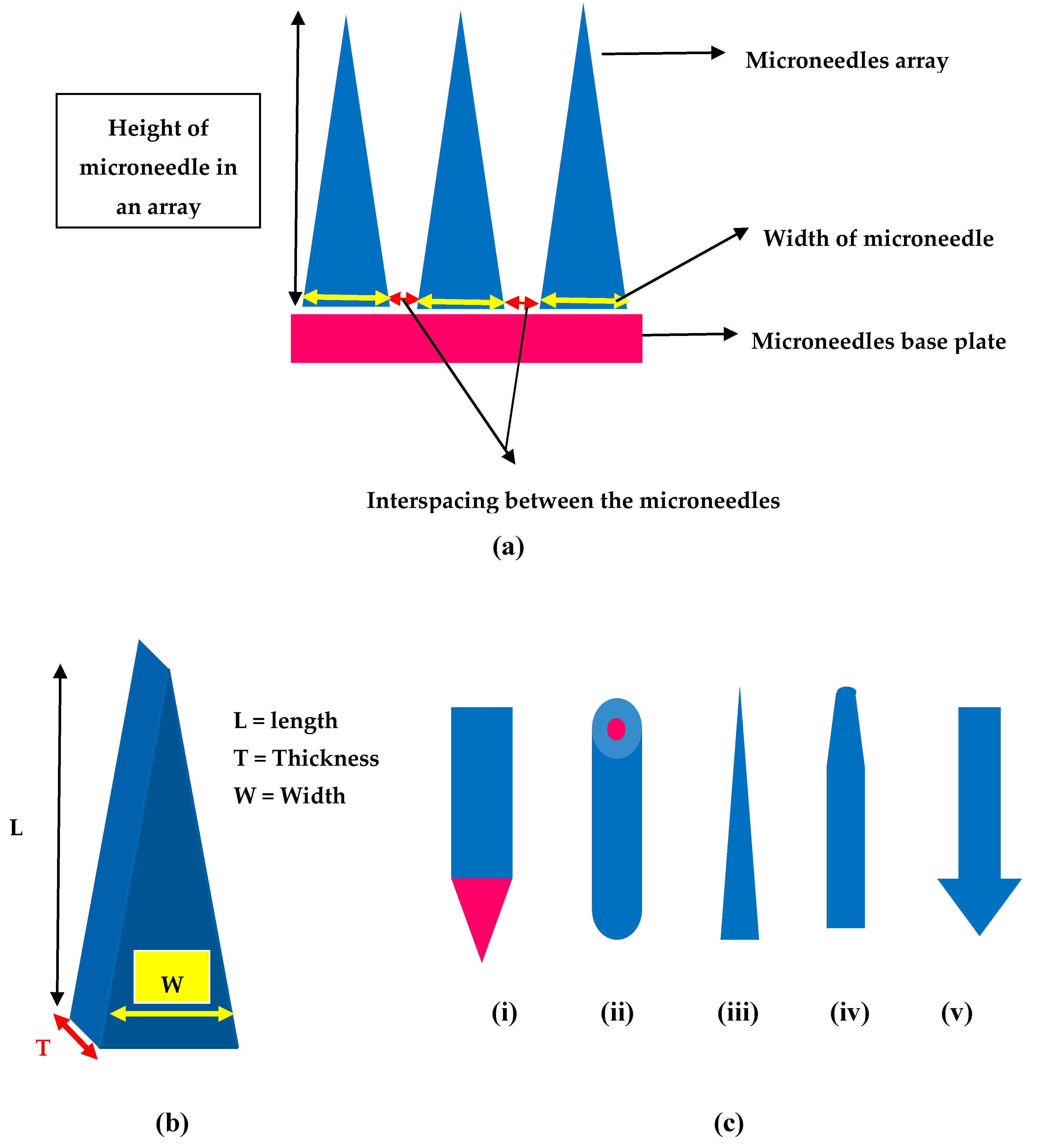

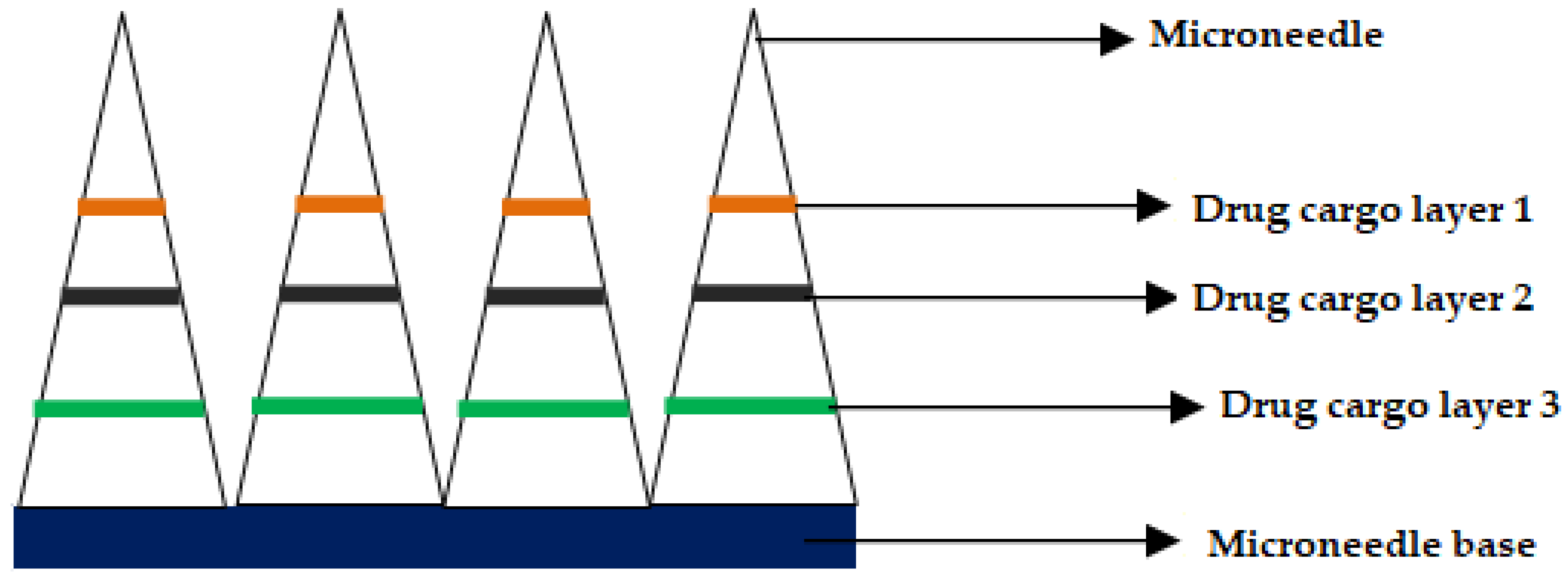

2.5. Design and Geometry

3. Different Cancer Treatments Using MNs

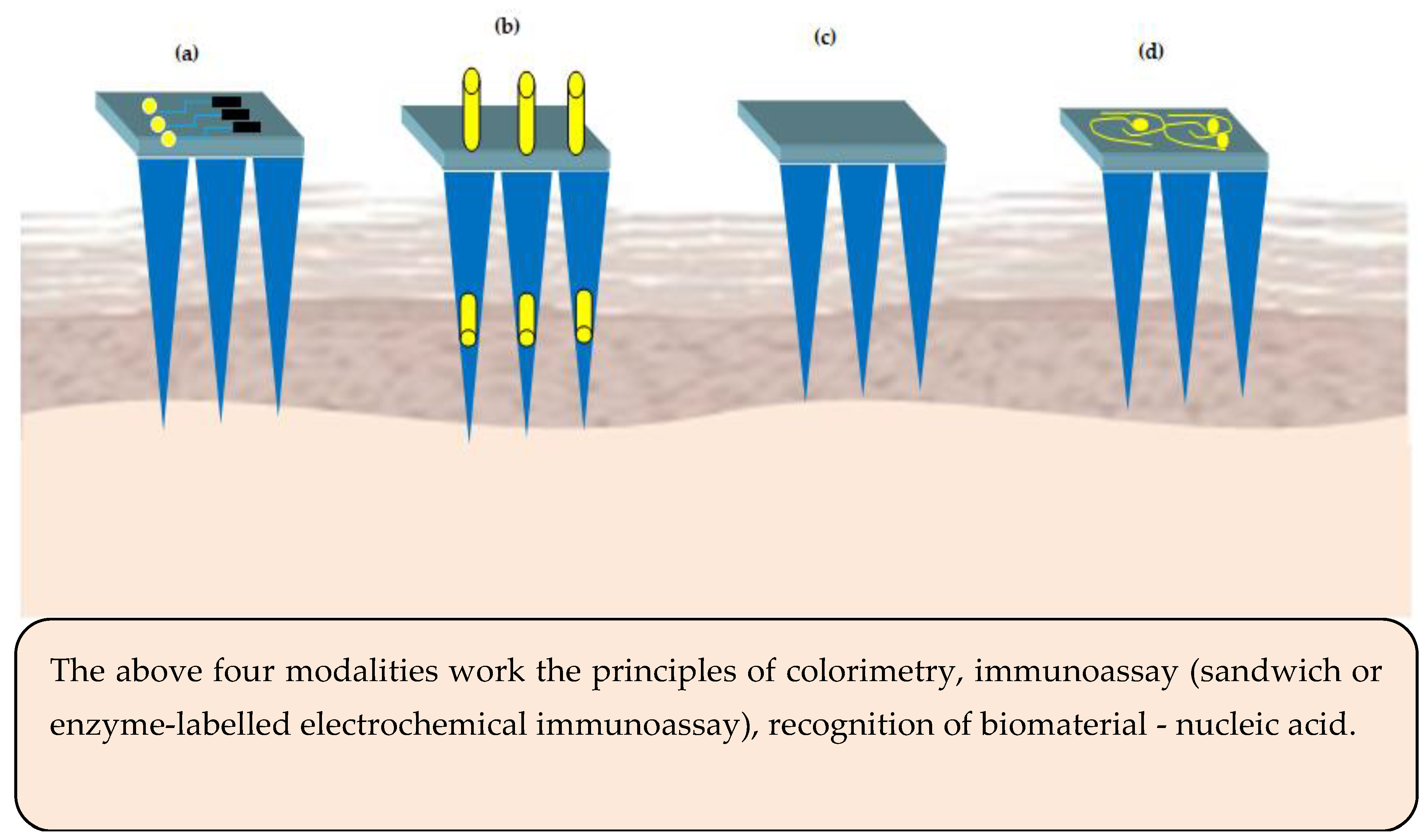

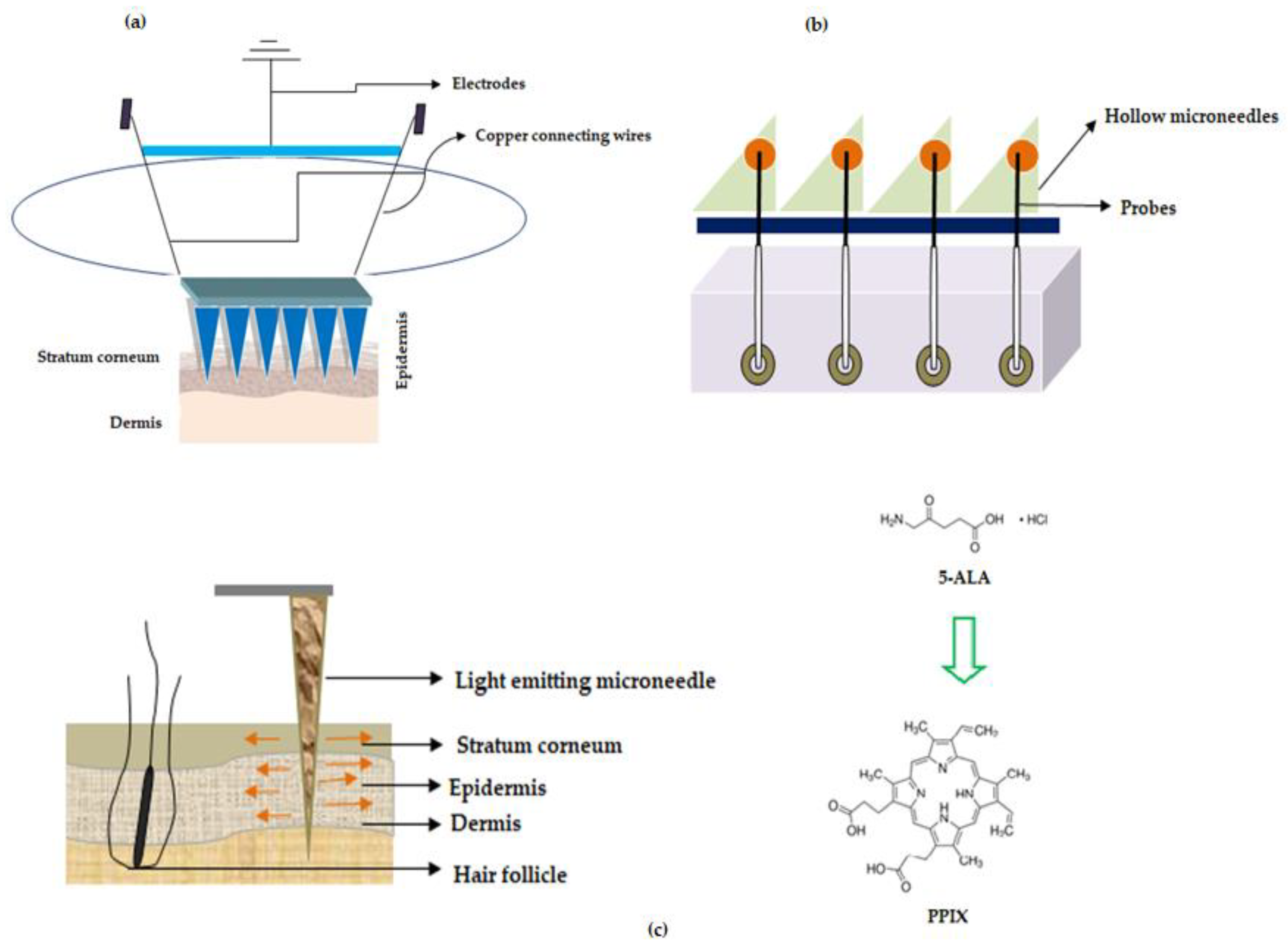

3.1. Sensor Technology Based MNs

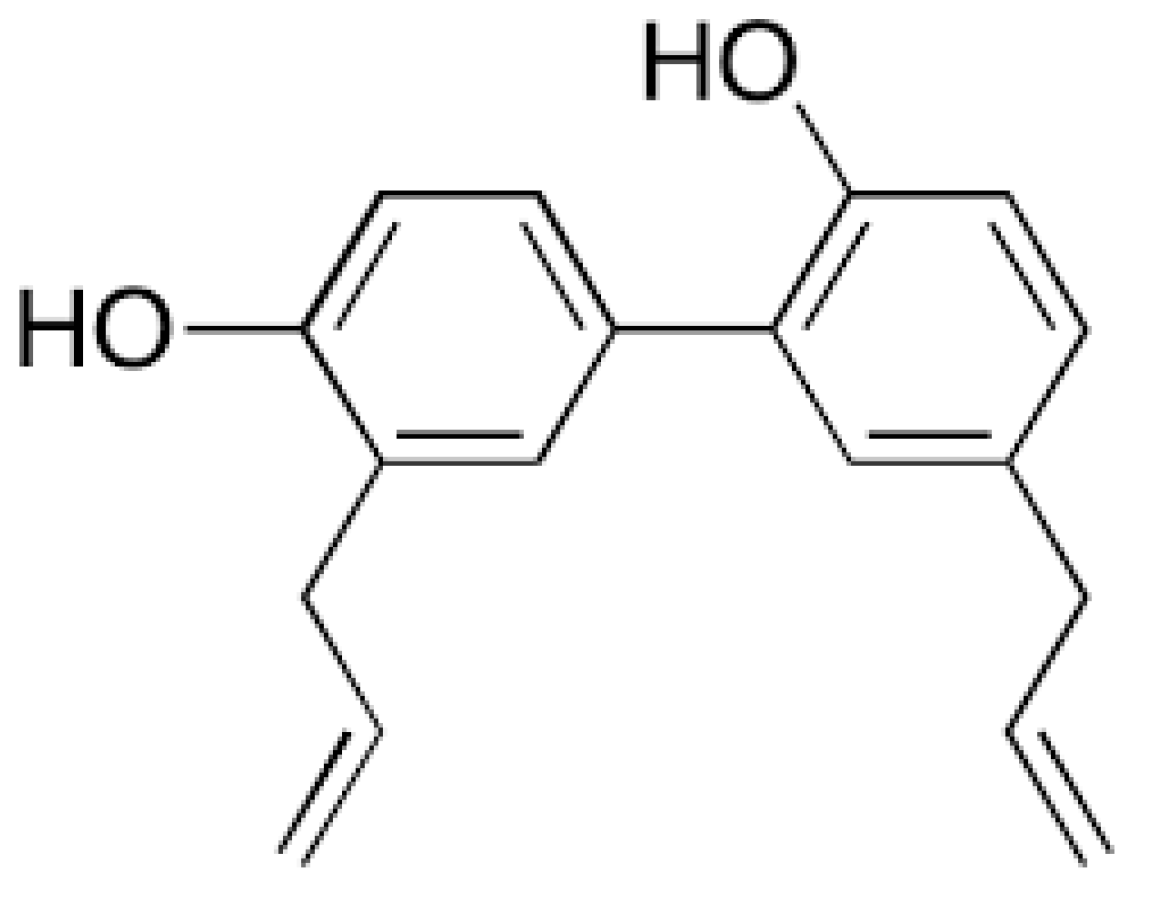

3.2. MNs in the Treatment of Breast Cancer

3.3. MNs in Skin Carcinoma

3.4. MNs for Prostate Cancer

4. More Recent Method of Manufacturing MNs—Printing Method

5. Clinical Trials (CTs) on MNs of Anti-Cancerous Drugs

5.1. Recruiting

5.2. Active, Not Recruiting

6. Limitations and Safety Concerns of MNs in Treatment of Cancer

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacGregor, R.R.; Graziani, A.L. Oral Administration of Antibiotics: A Rational Alternative to the Parenteral Route. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997, 24, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darji, M.A.; Lalge, R.M.; Marathe, S.P.; Mulay, T.D.; Fatima, T.; Alshammari, A.; Lee, H.K.; Repka, M.A.; Murthy, S.N. Excipient Stability in Oral Solid Dosage Forms: A Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 19, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, O.; Zweidorff, O.K.; Hjelde, T.; Rodland, E.A. Problemer med å svelgetabletter. Spørreundersøkelse fra allmennpraksis. Problems when swallowing tablets. A questionnaire study from general practice. TidsskrNorLaegeforen 1995, 115, 947–949. [Google Scholar]

- Maderuelo, C.; Lanao, J.M.; Zarzuelo, A. Enteric coating of oral solid dosage forms as a tool to improve drug bioavailability. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 138, 105019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pond, S.M.; Tozer, T.N. First-pass elimination. Basic concepts and clinical consequences. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1984, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.S.; Hardy, J.G.; Fara, J.W. Transit of pharmaceutical dosage forms through the small intestine. Gut 1986, 27, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pišlar, M.; Brelih, H.; Mrhar, A.; Bogataj, M. Analysis of small intestinal transit and colon arrival times of non-disintegrating tablets administered in the fasted state. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 75, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R.L. Drug Absorption in Gastrointestinal Disease with Particular Reference to Malabsorption Syndromes. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1977, 2, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.; Wong, I.C.K. Parenteral drug administration errors by nursing staff on an acute medical admissions ward during day duty. Drug Saf. 2001, 24, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, K.S.; Milewski, M.; Swadley, C.L.; Brogden, N.K.; Ghosh, P.; Stinchcomb, A.L. Challenges and opportunities in dermal/transdermal delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2010, 1, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, R.H. Transdermal Drug Delivery. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2010, 197, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hern, S.; Mortimer, P.S. Visualization of dermal blood vessels—Capillaroscopy. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1999, 24, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, A.C. Capillaroscopy and the measurement of capillary pressure. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000, 50, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, A.Y. Treatment of Palmar Hyperhidrosis with Tap Water Iontophoresis: A Randomized, Sham-Controlled, Single-Blind, and Parallel-Designed Clinical Trial. Ann. Dermatol. 2017, 29, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhote, V.; Bhatnagar, P.; Mishra, P.K.; Mahajan, S.C.; Mishra, D. Iontophoresis: A Potential Emergence of a Transdermal Drug Delivery System. Sci. Pharm. 2012, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Da, D.D. Prodrug Strategies for Enhancing the Percutaneous Absorption of Drugs. Molecules 2014, 19, 20780–20807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanthi, D.; Lakshmi, P. Effect of Chemical Enhancers in Transdermal Permeation of Alfuzosin Hydrochloride. ISRN Pharm. 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Karande, P.; Jain, A.; Ergun, K.; Kispersky, V.; Mitragotri, S. Design principles of chemical penetration enhancers for transdermal drug delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 4688–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Vyas, S. Topical liposomal system for localized and controlled drug delivery. J. Dermatol. Sci. 1996, 13, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, A.J.; Cordeiro, A.S.; Donnelly, R.F.; Montesinos, M.C.; Garrigues, T.; Zaera, A.M. Microneedle-Based Delivery: An Overview of Current Applications and Trends. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Me, J.F.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.F.; Dias, D.R.; Costa, E.C.; Correia, I.J. Thermo- and pH-responsive nano-in-micro particles for combinatorial drug delivery to cancer cells. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 104, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, J.M.; Park, W.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Yoon, M.S.; Choi, J.H.; Yoon, W.S.; et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes of adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma in uterine cervical cancer patients receiving surgical resection followed by radiotherapy: A multicenter retrospective study (KROG 13-10). Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 132, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.-J.; Chen, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, P.C. Circumventing Tumor Resistance to Chemotherapy by Nanotechnology, Multi-Drug Resistance in Cancer; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 596, pp. 467–488. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A.F.; Gaspar, V.M.; Costa, E.C.; De Melo-Diogo, D.; Machado, P.; Paquete, C.M.; Correia, I.J. Preparation of end-capped pH-sensitive mesoporous silica nanocarriers for on-demand drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 88, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, Y.W. Novel Drug Delivery System; Informa Health Care: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rathbone, M.J.; Hadgraft, J.; Roberts, M.S. (Eds.) Modified Release Drug Delivery Technology; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, R.F.; Singh, T.R.R.; Woolfson, A.D. Microneedle-based drug delivery systems: Microfabrication, drug delivery, and safety. Drug Deliv. 2010, 17, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Gill, H.S.; Andrews, S.N.; Prausnitz, M.R. Kinetics of skin resealing after insertion of microneedles in human subjects. J. Control. Release 2011, 154, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.D.; Wang, Q.L.; Liu, X.B.; Guo, X.D. Rapidly separating microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2016, 41, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, A.L.; Shearwood, C.; Ng, K.C.; Lu, J.; Moochhala, S. Transdermal microneedles for drug delivery applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2006, 132, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.; McAllister, D.V.; Allen, M.G.; Prausnitz, M.R. Microfabricated Microneedles: A Novel Approach to Transdermal Drug Delivery. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998, 87, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prausnitz, M.R. Microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghule, T.; Singhvi, G.; Dubey, S.K.; Pandey, M.M.; Gupta, G.; Singh, M.; Dua, K. Microneedles: A smart approach and increasing potential for transdermal drug delivery system. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martanto, W.; Baisch, S.M.; Costner, E.A.; Prausnitz, M.R.; Smith, M.K. Fluid dynamics in conically tapered microneedles. AIChE J. 2005, 51, 1599–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, K.; Norman, L. Means for Vaccinating. U.S. Patent 2,817,336, 24 December 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, K. Vaccinating Devices. U.S. Patent 3,136,314, 9 June 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel, M.S.; Place, V.A. Drug Delivery Device. U.S. Patent US3964482, 22 June 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Prausnitz, M.R. Engineering Microneedle Patches for Vaccination and Drug Delivery to Skin. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2017, 8, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei-Ze, L.; Mei-Rong, H.; Jian-Ping, Z.; Yong-Qiang, Z.; Bao-Hua, H.; Ting, L.; Yong, Z. Super-short solid silicon microneedles for transdermal drug delivery applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 389, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrañeta, E.; Lutton, R.E.; Woolfson, A.D.; Donnelly, R.F. Microneedle arrays as transdermal and intradermal drug delivery systems: Materials science, manufacture and commercial development. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2016, 104, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, H.; Banga, A.K. Formation and Closure of Microchannels in Skin Following Microporation. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, R.F.; Singh, T.R.R.; Alkilani, A.Z.; McCrudden, M.T.; Neill, S.O.; O’Mahony, C.; Armstrong, K.; McLoone, N.; Kole, P.; Woolfson, A.D. Hydrogel-forming microneedle arrays exhibit antimicrobial properties: Potential for enhanced patient safety. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 451, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, B.Z.; Wang, Q.L.; Jin, X.; Guo, X.D. Fabrication of coated polymer microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2017, 265, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, W.; Prausnitz, M.R. Individually coated microneedles for co-delivery of multiple compounds with different properties. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2018, 8, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliescu, F.; Dumitrescu-Ionescu, D.; Petrescu, M.; Iliescu, C. A Review on Transdermal Drug Delivery Using Microneedles: Current Research and Perspective. Ann. Acad. Rom. Sci. Ser. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2014, 7, 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsonanos, D.G.; Martin, M.D.P.; Zarnitsyn, V.G.; Sullivan, S.P.; Compans, R.W.; Prausnitz, M.R.; Skountzou, I. Transdermal Influenza Immunization with Vaccine-Coated Microneedle Arrays. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.R.S.; Garland, M.J.; Migalska, K.; Salvador, E.C.; Shaikh, R.; McCarthy, H.O.; Woolfson, A.D.; Donnelly, R.F. Influence of a pore-forming agent on swelling, network parameters, and permeability of poly(ethylene glycol)-crosslinked poly(methyl vinyl ether-co-maleic acid) hydrogels: Application in transdermal delivery systems. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 125, 2680–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.F.; Singh, T.R.R.; Garland, M.J.; Migalska, K.; Majithiya, R.; McCrudden, C.M.; Kole, P.L.; Mahmood, T.M.T.; McCarthy, H.O.; Woolfson, A.D. Hydrogel-Forming Microneedle Arrays for Enhanced Transdermal Drug Delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 4879–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, A.M.; McCrudden, M.T.; Vincente-Perez, E.; Dubois, A.V.; Ingram, R.J.; Larrañeta, E.; Kissenpfennig, A.; Donnelly, R.F. Design and characterisation of a dissolving microneedle patch for intradermal vaccination with heat-inactivated bacteria: A proof of concept study. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 549, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-J.; Han, M.-R.; Kim, J.-S.; Park, J.-H. A tearable dissolving microneedle system for shortening application time. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Yoshimitsu, J.-I.; Shiroyama, K.; Sugioka, N.; Takada, K. Self-dissolving microneedles for the percutaneous absorption of EPO in mice. J. Drug Target. 2006, 14, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.-E.; Hong, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, F.; Wei, L.L. Dissolving and biodegradable microneedle technologies for transdermal sustained delivery of drug and vaccine. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2013, 7, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.J.; Choi, S.-O.; Tong, N.T.; Aiyar, A.R.; Patel, S.R.; Prausnitz, M.R.; Allen, M.G. Hollow microneedles for intradermal injection fabricated by sacrificial micromolding and selective electrodeposition. Biomed. Microdevices 2013, 15, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martanto, W.; Moore, J.S.; Kashlan, O.; Kamath, R.; Wang, P.M.; O’Neal, J.M.; Prausnitz, M.R. Microinfusion Using Hollow Microneedles. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-C.; Huang, S.-F.; Lai, K.-Y.; Ling, M.-H. Fully embeddable chitosan microneedles as a sustained release depot for intradermal vaccination. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3077–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.D.; Zhang, X.P.; Shen, C.B.; Cui, Y.; Guo, X.D. The maximum possible amount of drug in rapidly separating microneedles. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Terry, R.N.; Tang, J.; Feng, M.R.; Schwendeman, S.P.; Prausnitz, M.R. Rapidly separable microneedle patch for the sustained release of a contraceptive. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharadhar, S.; Majumdar, A.; Dhoble, S.; Patravale, V. Microneedles for transdermal drug delivery: A systematic review. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2018, 45, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Yu, J.; Wen, D.; Kahkoska, A.R.; Gu, Z. Polymeric microneedles for transdermal protein delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 127, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Ahmad, R.; Khan, H.; Arshad, M.S.; Rasekh, M.; Hussain, A.; Walsh, S.E.; Li, X.; Chang, M.-W.; Ahmad, Z. Microneedle Coating Techniques for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.S.; Prausnitz, M.R. Coating Formulations for Microneedles. Pharm. Res. 2007, 24, 1369–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Allen, M.G.; Prausnitz, M.R. Polymer Microneedles for Controlled-Release Drug Delivery. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.; Lee, K.; Youngwook, C.H.O.; Oh, D. Composition for Improving Skin Conditions Comprising a Fragment of Human Heat Shock Protein 90a as an Active Ingredient. U.S. Patent 20180327464, 12 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moga, K.A.; Bickford, L.R.; Geil, R.D.; Dunn, S.S.; Pandya, A.A.; Wang, Y.; Fain, J.H.; Archuleta, C.F.; O’Neill, A.T.; DeSimone, J.M. Rapidly-Dissolvable Microneedle Patches Via a Highly Scalable and Reproducible Soft Lithography Approach. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 5060–5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James Paul, R.; Laurent, S. Iontophoretic Microneedle Device. U.S. Patent 20200206489, 7 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zsikó, S.; Csanyi, E.; Kovács, A.; Budai-Szűcs, M.; Gácsi, A.; Berkó, S. Methods to Evaluate Skin Penetration In Vitro. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, L.; Xu, C. Recent advances in the design of polymeric microneedles for transdermal drug delivery and biosensing. Lab. Chip 2017, 17, 1373–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchall, J.C.; Clemo, R.; Anstey, A.; John, D.N. Microneedles in Clinical Practice–An Exploratory Study Into the Opinions of Healthcare Professionals and the Public. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, K.; McElnay, J.C.; Donnelly, R.F. A qualitative assessment of the views of children and parents of premature babies on microneedle-mediated monitoring as a potential alternative to blood sampling. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2012, 20, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, K.; McElnay, J.C.; Donnelly, R.F. Children’s views on microneedle use as an alternative to blood sampling for patient monitoring. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2013, 22, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Hord, A.H.; Denson, D.D.; McAllister, D.V.; Smitra, S.; Allen, M.G.; Prausnitz, M.R. Lack of pain associated with microfabricated microneedles. Anesthesia Analg. 2001, 92, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, S.A.; Ng, C.-Y.; Simmers, R.; Moeckly, C.; Brandwein, D.; Gilbert, T.; Johnson, N.; Brown, K.; Alston, T.; Prochnow, G.; et al. Rapid Intradermal Delivery of Liquid Formulations Using a Hollow Microstructured Array. Pharm. Res. 2010, 28, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.I.; Smith, E.; John, D.N.; Kalavala, M.; Edwards, C.; Anstey, A.; Morrissey, A.; Birchall, J.C. Clinical administration of microneedles: Skin puncture, pain and sensation. Biomed. Microdevices 2009, 11, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardjito, T.; Donosepoetro, M.; Grange, J. The mantoux test in tuberculosis: Correlations between the diameters of the dermal responses and the serum protein levels. Tubercle 1981, 62, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrahian, C.; Zehrung, D.; Saxon, E.; Griswold, E.; Klaff, L. Clinical performance and safety of the ID adapter, a prototype intradermal delivery technology for vaccines, drugs, and diagnostic tests. Procedia Vaccinol. 2012, 6, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Reese, V.; Coler, R.; Carter, D.; Rolandi, M. Chitin Microneedles for an Easy-to-Use Tuberculosis Skin Test. Adv. Health Mater. 2013, 3, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, R.F.; Singh, T.R.R.; Tunney, M.M.; Morrow, D.I.J.; McCarron, P.A.; O’Mahony, C.; Woolfson, A.D. Microneedle Arrays Allow Lower Microbial Penetration Than Hypodermic Needles In Vitro. Pharm. Res. 2009, 26, 2513–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A.; Segre, J.A. Erratum: The skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 9, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Allen, M.G.; Prausnitz, M.R. Biodegradable polymer microneedles: Fabrication, mechanics and transdermal drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2005, 104, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hook, A.L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Yang, J.; Luckett, J.; Cockayne, A.; Atkinson, S.; Mei, Y.; Bayston, R.; Irvine, D.J.; Langer, R.; et al. Combinatorial discovery of polymers resistant to bacterial attachment. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente-Perez, E.M.; Larrañeta, E.; McCrudden, M.T.; Kissenpfennig, A.; Hegarty, S.; McCarthy, H.O.; Donnelly, R.F. Repeat application of microneedles does not alter skin appearance or barrier function and causes no measurable disturbance of serum biomarkers of infection, inflammation or immunity in mice in vivo. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 117, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brogden, N.K.; Milewski, M.; Ghosh, P.; Hardi, L.; Crofford, L.J.; Stinchcomb, A.L. Diclofenac delays micropore closure following microneedle treatment in human subjects. J. Control. Release 2012, 163, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Brogden, N.K.; Stinchcomb, A.L. Fluvastatin as a Micropore Lifetime Enhancer for Sustained Delivery Across Microneedle-Treated Skin. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 103, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psoriasis: Symptoms and Causes. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/psoriasis/symptoms-causes/syc-20355840 (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Katz, H.I. Topical corticosteroids. Dermatol. Clin. 1995, 13, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, H.L.; Fortune, D.G.; O’Sullivan, T.M.; Main, C.J.; Griffiths, C.E. Patients with psoriasis and their compliance with medication. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999, 41, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemulapalli, V.; Yang, Y.; Friden, P.M.; Banga, A.K. Synergistic effect of iontophoresis and soluble microneedles for transdermal delivery of methotrexate. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2008, 60, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjar, M.; Arbiser, J.L.; Coulon, R.; Banga, A.K. Localized delivery of a lipophilic proteasome inhibitor into human skin for treatment of psoriasis. J. Drug Target. 2016, 24, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indermun, S.; Luttge, R.; Choonara, Y.E.; Kumar, P.; Du Toit, L.C.; Modi, G.; Pillay, V. Current advances in the fabrication of microneedles for transdermal delivery. J. Control. Release 2014, 185, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.M.; Cornwell, M.; Hill, J.; Prausnitz, M.R. Precise Microinjection into Skin Using Hollow Microneedles. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Prausnitz, M.R. Dissolving microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2113–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.C.; Ling, M.H.; Lai, K.Y.; Pramudityo, E. Chitosan microneedle patches for sustained transdermal delivery of macromolecules. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 4022–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodhale, D.W.; Nisar, A.; Afzulpurkar, N. Structural and microfluidic analysis of hollow side-open polymeric microneedles for transdermal drug delivery applications. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2010, 8, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.; Kim, B. Functionalized microneedles for continuous glucose monitoring. Nano Converg. 2018, 5, 28, Erratum in Nano Converg. 2018, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardano, P.; Rea, I.; De Stefano, L. Microneedles-based electrochemical sensors: New tools for advanced biosensing. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2019, 17, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Hatware, K.; Bhadane, P.; Sindhikar, S.; Mishra, D. Recent advances in microneedle composites for biomedical applications: Advanced drug delivery technologies. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 103, 109717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, B.; Venugopal, N.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Distribution of particles, small molecules and polymeric formulation excipients in the suprachoroidal space after microneedle injection. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 153, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, A.P.; Crichton, M.L.; Falconer, R.J.; Meliga, S.; Chen, X.; Fernando, G.J.; Huang, H.; Kendall, M.A.F. Formulations for microprojection/microneedle vaccine delivery: Structure, strength and release profiles. J. Control. Release 2016, 225, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Gomaa, Y.; Li, W. Microneedle patch drug delivery in the gut. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1471–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, A.F.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Jacinto, T.A.; Miguel, S.P.; Costa, E.C.; Correia, I.J. Microneedle-based delivery devices for cancer therapy: A review. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 148, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, W. Semiconductor microelectronic sensors. In Advances in Solid State Physics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 22, pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, D.A.; McLean, N.V. A colorimetric assay for the measurement of d-glucose consumption by cultured cells. Anal. Biochem. 1989, 177, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sulaiman, D.; Chang, J.Y.H.; Bennett, N.R.; Topouzi, H.; Higgins, C.A.; Irvine, D.J.; Ladame, S. Hydrogel-Coated Microneedle Arrays for Minimally Invasive Sampling and Sensing of Specific Circulating Nucleic Acids from Skin Interstitial Fluid. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 9620–9628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goud, K.Y.; Moonla, C.; Mishra, R.K.; Yu, C.; Narayan, R.; Litvan, I.; Wang, J. Wearable Electrochemical Microneedle Sensor for Continuous Monitoring of Levodopa: Toward Parkinson Management. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 2196–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, S.K.; Dohee, K.E.U.M.; Jung, H.S.; Kim, H.; Shin, M.H. Micro-Needle and Sensor for Detecting Nitrogen Monooxide Comprising the Same. U.S. Patent 20160174885, 16 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Windmiller, J.R.; Narayan, R.; Miller, P.; Polsky, R.; Edwards, T.L. Microneedle Arrays for Biosensing and Drug Delivery. U.S. Patent US9737247B2, 22 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rylander, C.; Kosoglu, M.A.; Hood, R.L.; Robertson, J.L.; Rossmeisl, J.H.; Grant, D.C.; Rylander, M.N. Fiber Array for Optical Imaging and Therapeutics. U.S. Patent 20130338627, 5 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K.; Lee, C.H.; Gill, H.S. 5-Aminolevulinic acid coated microneedles for photodynamic therapy of skin tumors. J. Control. Release 2016, 239, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.F.; Morrow, D.I.; McCarron, P.A.; Woolfson, A.D.; Morrissey, A.; Juzenas, P.; Juzeniene, A.; Iani, V.; McCarthy, H.O.; Moan, J. Microneedle-mediated intradermal delivery of 5-aminolevulinic acid: Potential for enhanced topical photodynamic therapy. J. Control. Release 2008, 129, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z.; Djaldetti, M. 5-aminolevulinic acid stimulation of porphyrin and hemoglobin synthesis by uninduced friend erythroleukemic cells. Cell Differ. 1979, 8, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Son, S.; Ochyl, L.J.; Kuai, R.; Schwendeman, A.; Moon, J.J. Chemo-photothermal therapy combination elicits anti-tumor immunity against advanced metastatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.F.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Jacinto, T.A.; Miguel, S.P.; Costa, E.C.; Correia, I.J. Poly (vinyl alcohol)/chitosan layer-by-layer microneedles for cancer chemo-photothermal therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 576, 118907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Bankar, N.G.; Kulkarni, M.V.; Venuganti, V.V.K. Dissolvable microneedle patch containing doxorubicin and docetaxel is effective in 4T1 xenografted breast cancer mouse model. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 556, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Dong, M.; Zhang, T.; Peng, J.; Jia, Y.; Cao, Y.; Qian, Z. Novel Approach of Using Near-Infrared Responsive PEGylated Gold Nanorod Coated Poly(l-lactide) Microneedles to Enhance the Antitumor Efficiency of Docetaxel-Loaded MPEG-PDLLA Micelles for Treating an A431 Tumor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 15317–15327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Chen, Y.; He, X.; Yang, F.; Han, R.; Yang, C.; Li, W.; Qian, Z. Near-infrared responsive 5-fluorouracil and indocyanine green loaded MPEG-PCL nanoparticle integrated with dissolvable microneedle for skin cancer therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Zheng, M.; Yu, X.; Than, A.; Seeni, R.Z.; Kang, R.; Tian, J.; Khanh, D.P.; Liu, L.; Chen, P.; et al. A Swellable Microneedle Patch to Rapidly Extract Skin Interstitial Fluid for Timely Metabolic Analysis. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.G.; Joung, H.A.; Noh, H.; Song, M.B.; Kim, M.G.; Jung, H. One-touch-activated blood multidiagnostic system using a minimally invasive hollow microneedle integrated with a paper-based sensor. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 3286–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, B.; Desai, S.P.; Tierney, M.J.; Tamada, J.A.; Jina, A.N. Effect of microneedles shape on skin penetration and minimally invasive continuous glucose monitoring in vivo. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2013, 203, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windmiller, J.R.; Valdés-Ramírez, G.; Zhou, N.; Zhou, M.; Miller, P.R.; Jin, C.; Brozik, S.M.; Polsky, R.; Katz, E.; Narayan, R.J.; et al. Bicomponent Microneedle Array Biosensor for Minimally-Invasive Glutamate Monitoring. Electroanalysis 2011, 23, 2302–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.R.; Skoog, S.A.; Edwards, T.L.; Lopez, D.M.; Wheeler, D.R.; Arango, D.C.; Xiao, X.; Brozik, S.M.; Wang, J.; Polsky, R.; et al. Multiplexed microneedle-based biosensor array for characterization of metabolic acidosis. Talanta 2012, 88, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windmiller, J.R.; Zhou, N.; Chuang, M.-C.; Valdés-Ramírez, G.; Santhosh, P.; Miller, P.R.; Narayan, R.; Wang, J. Microneedle array-based carbon paste amperometric sensors and biosensors. Analyst 2011, 136, 1846–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Chen, H.-J.; Li, X.; Huang, X.; Wu, Q.; He, G.; Hang, T.; Yang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Li, E.; et al. Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanohybrid-Assembled Microneedles as Mini-Invasive Electrodes for Real-Time Transdermal Biosensing. Small 2019, 15, 1804298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, D.H.; Jung, H.S.; Wang, T.; Shin, M.H.; Kim, Y.-E.; Kim, K.H.; Ahn, G.-O.; Hahn, S.K. Microneedle Biosensor for Real-Time Electrical Detection of Nitric Oxide for In Situ Cancer Diagnosis During Endomicroscopy. Adv. Health Mater. 2015, 4, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Li, Y.; Xie, H.; Shu, Q.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.-L.; Liang, F.; Wang, H.; Huang, W.-H.; Zhang, G.-J. A sensitive acupuncture needle microsensor for real-time monitoring of nitric oxide in acupoints of rats. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, A.; Boopathy, A.V.; Lam, L.K.W.; Moynihan, K.D.; Welch, M.E.; Bennett, N.R.; Turvey, M.E.; Thai, N.; Van, J.H.; Love, J.C.; et al. Cell and fluid sampling microneedle patches for monitoring skin-resident immunity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaar2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.R.; Xiao, X.; Brener, I.; Burckel, D.B.; Narayan, R.; Polsky, R. Diagnostic Devices: Microneedle-Based Transdermal Sensor for On-Chip Potentiometric Determination of K+. Adv. Health Mater. 2014, 3, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilla, M.; Cuartero, M.; Sánchez, S.P.; Rajabi, M.; Roxhed, N.; Niklaus, F.; Crespo, G.A. Wearable All-Solid-State Potentiometric Microneedle Patch for Intradermal Potassium Detection. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 1578–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chablani, L.; Tawde, S.A.; Akalkotkar, A.; D’Souza, M.J. Evaluation of a Particulate Breast Cancer Vaccine Delivered via Skin. AAPS J. 2019, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Giaccia, A.J. The unique physiology of solid tumors: Opportunities (and problems) for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Labala, S.; Jose, A.; Chawla, S.R.; Khan, M.S.; Bhatnagar, S.; Kulkarni, O.P.; Venuganti, V.V.K. Effective melanoma cancer suppression by iontophoretic co-delivery of STAT3 siRNA and imatinib using gold nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 525, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-F.; Huang, C.-M. Decreasing Systemic Toxicity Via Transdermal Delivery of Anticancer Drugs. Curr. Drug Metab. 2008, 9, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, G.A. Breast conserving therapy: A surgical technique where little can mean more. J. Surg. Tech. Case Rep. 2011, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, S.M.; Barsky, S.H. Anatomy of the nipple and breast ducts revisited. Cancer 2004, 101, 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, K.; Averineni, R.; Sahdev, P.; Perumal, O. Transpapillary Drug Delivery to the Breast. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.M.; Davison, Z.; Heard, C.M. In vitro delivery of anti-breast cancer agents directly via the mammary papilla (nipple). Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 387, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Ye, Y.; Gu, Z. Local delivery of checkpoints antibodies. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2017, 13, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zeng, M.; Shan, H.; Tong, C. Microneedle Patches as Drug and Vaccine Delivery Platform. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 2413–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Kumari, P.; Pattarabhiran, S.P.; Venuganti, V.V.K. Zein Microneedles for Localized Delivery of Chemotherapeutic Agents to Treat Breast Cancer: Drug Loading, Release Behavior, and Skin Permeation Studies. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018, 19, 1818–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Chawla, S.R.; Kulkarni, O.P.; Venuganti, V.V.K. Zein Microneedles for Transcutaneous Vaccine Delivery: Fabrication, Characterization, and In Vivo Evaluation Using Ovalbumin as the Model Antigen. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagalingam, A.; Arbiser, J.L.; Bonner, M.Y.; Saxena, N.K.; Sharma, D. Honokiol activates AMP-activated protein kinase in breast cancer cells via an LKB1-dependent pathway and inhibits breast carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemura, K.; Arbiser, J.L.; Sun, S.-Y.; Zayzafoon, M.; Johnstone, P.A.; Fujisawa, M.; Gotoh, A.; Weksler, B.; Zhau, H.E.; Chung, L.W. Honokiol, a natural plant product, inhibits the bone metastatic growth of human prostate cancer cells. Cancer 2007, 109, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Qian, Y.; Geng, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Xie, H.; Yan, S.; Jiang, G.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, S. Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in honokiol-induced apoptosis in a human hepatoma cell line (hepG2). Liver Int. 2008, 28, 1458–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Patel, M.G.; Bakshi, P.; Sharma, D.; Banga, A.K. Enhancement in the Transdermal and Localized Delivery of Honokiol Through Breast Tissue. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018, 19, 3501–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojeiko, G.; De Brito, M.; Salata, G.C.; Lopes, L.B. Combination of microneedles and microemulsions to increase celecoxib topical delivery for potential application in chemoprevention of breast cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 560, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, A.; Narvenker, R.; Prabhakar, B.; Shende, P. Strategic consideration for effective chemotherapeutic transportation via transpapillary route in breast cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 586, 119563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, J.; You, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, A.; Xin, H.; Wang, X. Local extraction and detection of early stage breast cancers through a microneedle and nano-Ag/MBL film based painless and blood-free strategy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 109, 110402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, A.; Khayamian, M.A.; Saghafi, M.; Shalileh, S.; Katebi, P.; Assadi, S.; Gilani, A.; Parizi, M.S.; Vanaei, S.; Esmailinejad, M.R.; et al. Microneedle-Based Generation of Microbubbles in Cancer Tumors to Improve Ultrasound-Assisted Drug Delivery. Adv. Health Mater. 2019, 8, e1900613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, M.F.; Sousa, J.S.; Pais, A.C. Skin cancer and new treatment perspectives: A review. Cancer Lett. 2015, 357, 8–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aractingi, S.; Kanitakis, J.; Euvrard, S.; Le Danff, C.; Péguillet, I.; Khosrotehrani, K.; Lantz, O.; Carosella, E.D. Skin Carcinoma Arising From Donor Cells in a Kidney Transplant Recipient. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 1755–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Mariotto, A.B.; Rowland, J.H.; Yabroff, K.R.; Alfano, C.M.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.L.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fan, T.; Xie, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Xue, P.; Zheng, T.; Chen, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhang, H. Advances in nanomaterials for photodynamic therapy applications: Status and challenges. Biomaterials 2020, 237, 119827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Dai, H.; Zeng, B.; Zheng, X.; Yi, C.; Jiang, N.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X. On-demand drug release and re-absorption from pirarubicin loaded Fe3O4@ZnO core-shell nanoparticles for targeting infusion chemotherapy for urethral carcinoma. Mater. Express 2019, 9, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.S.; June, C.H.; Langer, R.; Mitchell, M.J. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, X.; Yang, F.; Qian, Z. Microneedles-Based Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems: A Review. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2017, 13, 1581–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Hao, Y.; Yuan, L.; Pradhan, S.; Shrestha, K.; Pradhan, O.; Liu, H.; Li, W. Nano-formulations for transdermal drug delivery: A review. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2018, 29, 1713–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wen, D.; Milligan, J.; Bellotti, A.; Huang, L.; et al. A melanin-mediated cancer immunotherapy patch. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, eaan5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Wang, C.; Ye, Y. Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy by Microneedle Patch-Assisted Delivery. U.S. Patent 20190083703; Status: Pending,

- Wang, C.; Ye, Y.; Hochu, G.M.; Sadeghifar, H.; Gu, Z. Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy by Microneedle Patch-Assisted Delivery of Anti-PD1 Antibody. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 2334–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcomb, A.L.; Banks, S.L.; Golinski, M.J.; Howard, J.L.; Hammell, D.C. Use of Cannabidiol Prodrugs in Topical and Transdermal Administration with Microneedles. U.S. Patent US9533942B2, 3 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Edelson, J. Transdermal Delivery of Large Agents. International Patent WO 2018/093465, 21 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Edelson, J. Improved Delivery of Large Agents. International Patent WO 2020/117564, 6 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Mantha, S.N.; Crowder, D.C.; Chinchilla, S.; Shah, K.N.; Yun, Y.H.; Wicker, R.B.; Choi, J.-W. Microstereolithography and characterization of poly(propylene fumarate)-based drug-loaded microneedle arrays. Biofabrication 2015, 7, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, I.M.; Tekko, I.A.; Matchett, K.B.; Arnaut, L.G.; Silva, C.S.; McCarthy, H.O.; Donnelly, R.F. Intradermal Delivery of a Near-Infrared Photosensitizer Using Dissolving Microneedle Arrays. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 107, 2439–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mayahy, M.H.; Sabri, A.H.; Rutland, C.S.; Holmes, A.; McKenna, J.; Marlow, M.; Scurr, D.J. Insight into imiquimod skin permeation and increased delivery using microneedle pre-treatment. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 139, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, A.; Ogilvie, J.; McKenna, J.; Segal, J.; Scurr, D.; Marlow, M. Intradermal Delivery of an Immunomodulator for Basal Cell Carcinoma; Expanding the Mechanistic Insight into Solid Microneedle-Enhanced Delivery of Hydrophobic Molecules. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 2925–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falo, D.L., Jr.; Erdos, G.; Ozdoganlar, O.B. Microneedle Arrays for Cancer Therapy Applications. U.S. Patent US20160136407A1, 6 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C.; Zhang, R. Semiconductor Microneedle Assembly Based on Gene Therapy, Manufacturing Method and Manufacturing Mold. Chinese Patent CN106426729A, 9 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Cancer Research Fund International. Cancer Facts and Figures: Worldwide Data. 2018. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer/cancer-trends/worldwide-cancer-data (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Morote, J.; Maldonado, X.; Morales-Bárrera, R. Prostate cancer (English Edition). Med. Clín. 2016, 146, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy, N. Futile: Prostate Cancer Vaccine Phase 3 Trial Ends, Medscape. 2017. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/885877 (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- McCaffrey, J.; Donnelly, R.F.; McCarthy, H.O. Microneedles: An innovative platform for gene delivery. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2015, 5, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-Y.; Tsai, H.-T.; Tzai, T.-S. Transdermal Delivery of Luteinizing Hormone-releasing Hormone with Chitosan Microneedles: A Promising Tool for Androgen Deprivation Therapy. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 6791–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-O.; Kim, Y.-C.; Lee, J.W.; Park, J.-H.; Prausnitz, M.R.; Allen, M.G. Intracellular Protein Delivery and Gene Transfection by Electroporation Using a Microneedle Electrode Array. Small 2012, 8, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.-O.; Kim, Y.C.; Park, J.-H.; Hutcheson, J.; Gill, H.S.; Yoon, Y.-K.; Prausnitz, M.R.; Allen, M.G. An electrically active microneedle array for electroporation. Biomed. Microdevices 2010, 12, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, G.; Ali, A.A.; McErlean, E.; Mulholland, E.J.; Short, A.; McCrudden, C.M.; McCaffrey, J.; Robson, T.; Boyd, P.; Coulter, J.A.; et al. DNA vaccination via RALA nanoparticles in a microneedle delivery system induces a potent immune response against the endogenous prostate cancer stem cell antigen. Acta Biomater. 2019, 96, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gittard, S.D.; Miller, P.R.; Jin, C.; Martin, T.N.; Boehm, R.D.; Chisholm, B.J.; Stafslien, S.J.; Daniels, J.W.; Cilz, N.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; et al. Deposition of antimicrobial coatings on microstereolithography-fabricated microneedles. JOM 2011, 63, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, J.; Scoutaris, N.; Klepetsanis, P.; Chowdhry, B.; Prausnitz, M.R.; Douroumis, D. Inkjet printing of transdermal microneedles for the delivery of anticancer agents. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 494, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, J.; Scoutaris, N.; Economidou, S.N.; Giraud, C.; Chowdhry, B.Z.; Donnelly, R.F.; Douroumis, D. 3D printed microneedles for anticancer therapy of skin tumours. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 107, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US National Library of Medicine. 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=microneedles&cond=Cancer&cntry=US&Search=Apply&recrs=a&age_v=&gndr=&type=&rslt= (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Bediz, B.; Korkmaz, E.; Khilwani, R.; Donahue, C.; Erdos, G.; Falo, L.D.; Ozdoganlar, O.B. Dissolvable Microneedle Arrays for Intradermal Delivery of Biologics: Fabrication and Application. Pharm. Res. 2014, 31, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munavalli, G.S.; Zelickson, B.D.; Selim, M.M.; Kilmer, S.L.; Rohrer, T.E.; Newman, J.; Jauregui, L.; Knape, W.A.; Ebbers, E.; Uecker, D.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field Treatment of Sebaceous Gland Hyperplasia. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruza, G.J.; Zelickson, B.D.; Selim, M.M.; Rohrer, T.E.; Newman, J.; Park, H.; Jauregui, L.; Nuccitelli, R.; Knape, W.A.; Ebbers, E.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field Treatment of Seborrheic Keratoses. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahn, J.D.; Deshmukh, A.; Pisano, A.P.; Liepmann, D. Continuous On-Chip Micropumping for Microneedle Enhanced Drug Delivery. Biomed. Microdevices 2004, 6, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimardani, V.; Abolmaali, S.; Tamaddon, A.M.; Ashfaq, M. Recent advances on microneedle arrays-mediated technology in cancer diagnosis and therapy. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, H.S.; Denson, D.D.; Burris, B.A.; Prausnitz, M.R. Effect of Microneedle Design on Pain in Human Subjects. Clin. J. Pain 2008, 24, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.S.; Prausnitz, M.R. Does Needle Size Matter? J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2007, 1, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, S.M.; Caussin, J.; Pavel, S.; Bouwstra, J.A. In vivo assessment of safety of microneedle arrays in human skin. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 35, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, X.H.M.; Van Der Linde, P.; Homburg, E.F.G.A.; Van Breemen, L.C.; De Jong, A.; Lüttge, R.R. Insertion Process of Ceramic Nanoporous Microneedles by Means of a Novel Mechanical Applicator Design. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivamani, R.K.; Liepmann, D.; Maibach, H.I. Microneedles and transdermal applications. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2006, 4, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, H. Is galvanic corrosion between titanium alloy and stainless steel spinal implants a clinical concern? Spine J. 2004, 4, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of the Analyte | Principle Involved in Detection | Structure and Materials for Sensor | Test Subject | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose |

|

|

| [117,118,119] |

| Glutamate | Electrochemistry | Hollow or solid MNs of a polymer | - | [120] |

| Lactate | Electrochemistry | Hollow or solid MNs of polymer along with carbon paste or carbon nanotubes | - | [121,122] |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Electrochemistry | Solid MNs with platinum or gold electrodes | Mouse | [123] |

| Nitric oxide | Electrochemistry | Solid MNs of a polymer or metal with hemin or graphene that is functionalized. | Melanoma mouse Rat | [124,125] |

| T cell | Immune response | Solid MNs of polymer with antigens (nano-capsule) | Human skin | [126] |

| Potassium | Electrochemistry | Hollow MNs of polymer or metal with ion specific electrode | Porcine skin | [127,128] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seetharam, A.A.; Choudhry, H.; Bakhrebah, M.A.; Abdulaal, W.H.; Gupta, M.S.; Rizvi, S.M.D.; Alam, Q.; Siddaramaiah; Gowda, D.V.; Moin, A. Microneedles Drug Delivery Systems for Treatment of Cancer: A Recent Update. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12111101

Seetharam AA, Choudhry H, Bakhrebah MA, Abdulaal WH, Gupta MS, Rizvi SMD, Alam Q, Siddaramaiah, Gowda DV, Moin A. Microneedles Drug Delivery Systems for Treatment of Cancer: A Recent Update. Pharmaceutics. 2020; 12(11):1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12111101

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeetharam, Aravindram Attiguppe, Hani Choudhry, Muhammed A. Bakhrebah, Wesam H. Abdulaal, Maram Suresh Gupta, Syed Mohd Danish Rizvi, Qamre Alam, Siddaramaiah, Devegowda Vishakante Gowda, and Afrasim Moin. 2020. "Microneedles Drug Delivery Systems for Treatment of Cancer: A Recent Update" Pharmaceutics 12, no. 11: 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12111101

APA StyleSeetharam, A. A., Choudhry, H., Bakhrebah, M. A., Abdulaal, W. H., Gupta, M. S., Rizvi, S. M. D., Alam, Q., Siddaramaiah, Gowda, D. V., & Moin, A. (2020). Microneedles Drug Delivery Systems for Treatment of Cancer: A Recent Update. Pharmaceutics, 12(11), 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12111101