Abstract

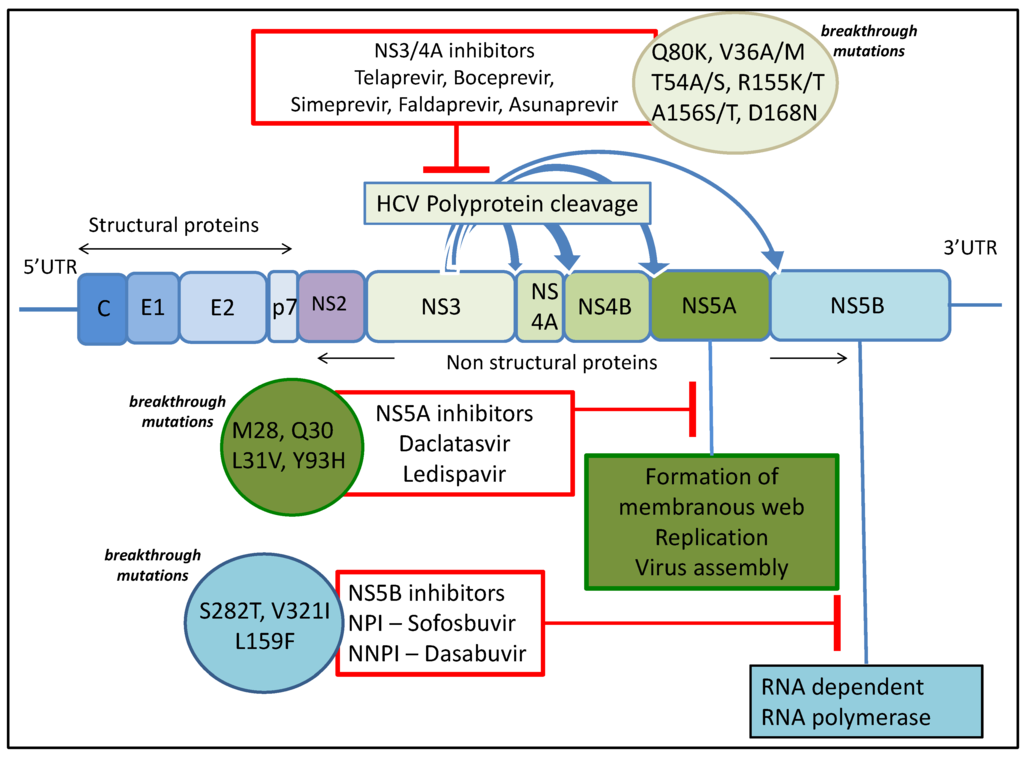

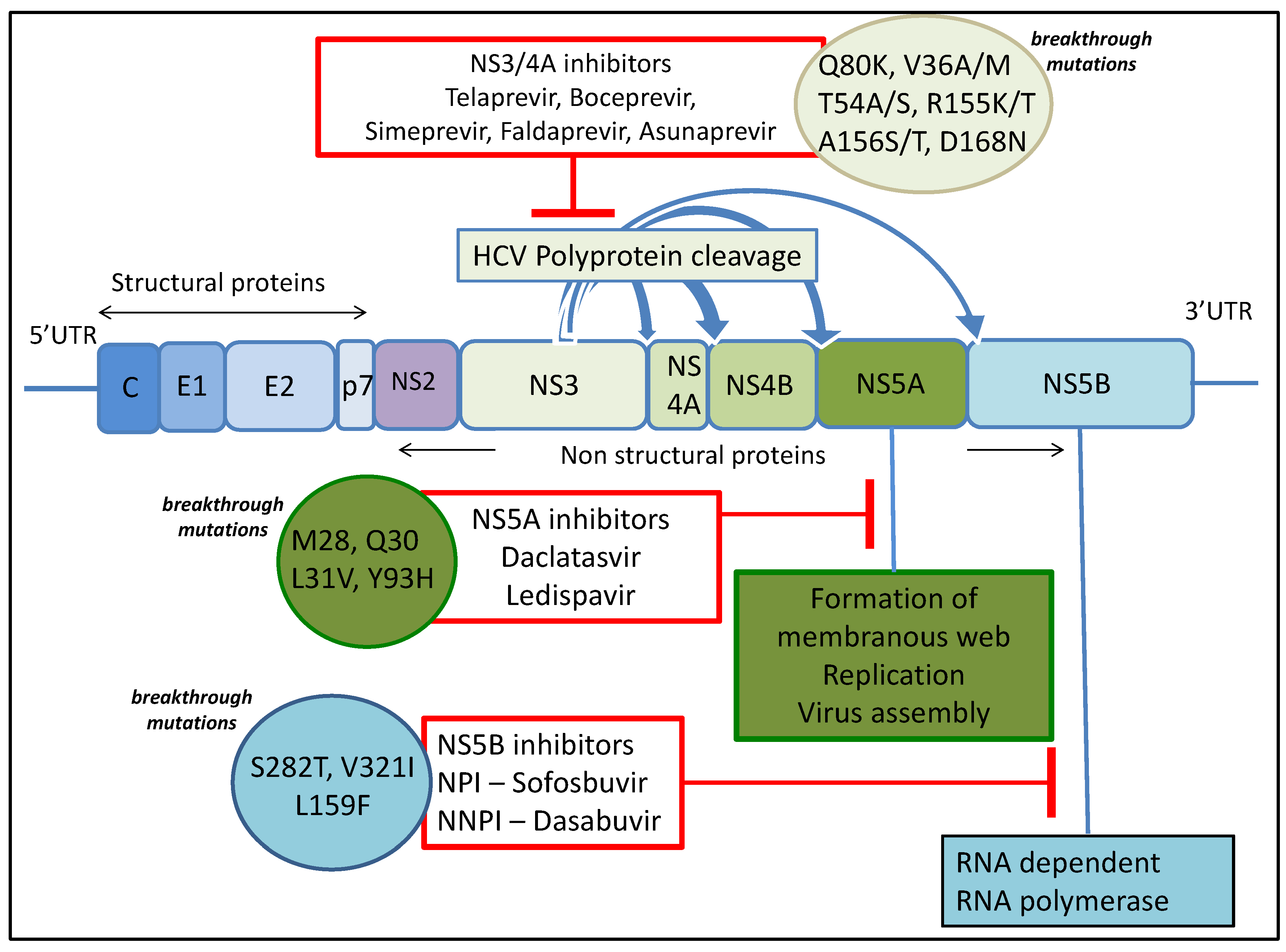

There has been a remarkable transformation in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in recent years with the development of direct acting antiviral agents targeting virus encoded proteins important for viral replication including NS3/4A, NS5A and NS5B. These agents have shown high sustained viral response (SVR) rates of more than 90% in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials; however, this is slightly lower in real-life cohorts. Hepatitis C virus resistant variants are seen in most patients who do not achieve SVR due to selection and outgrowth of resistant hepatitis C virus variants within a given host. These resistance associated mutations depend on the class of direct-acting antiviral drugs used and also vary between hepatitis C virus genotypes and subtypes. The understanding of these mutations has a clear clinical implication in terms of choice and combination of drugs used. In this review, we describe mechanism of action of currently available drugs and summarize clinically relevant resistance data.

1. Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major global health problem and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. The most recent estimate showed an increase in the prevalence of HCV infection over last 15 years from 2.3% to 2.8%. This equates to 170 million people who are chronically infected worldwide and 3–4 million developing new infection with HCV each year [1,2] while 350,000 people die every year due to HCV related complications [3].

Following exposure to HCV, only a minority of cases are able to clear the virus spontaneously. The majority of individuals (approximately 80%) develop chronic infection with persistent viremia and chronic hepatitis. This frequently results in the development of progressive liver fibrosis and ultimately cirrhosis, with its attendant risks of developing liver failure and hepatocellular cancer [2,4].

Until 2011, HCV standard-of-care treatment consisted of interferon alpha and ribavirin for several months, which is associated with detrimental side effects affecting compliance and poor outcomes. However, new and promising direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have recently become available with more in the development pipeline resulting in a remarkable transformation in treatment of HCV. DAAs are drugs targeting specific HCV encoded proteins resulting in disruption of the viral life cycle. A number of DAAs are either approved or in phases of advanced development and clinical trials. The first generation of DAAs was administered in conjunction with pegylated interferon, so while the efficacy of treatment increased, the issues with side-effects remained. However, the incorporation of next-generation DAAs into the antiviral cocktail is leading to interferon-free regimens in clinical practice. Although the first generation of DAAs (NS3/4A inhibitors Telaprevir and Boceprevir) were co-administered with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, thereby adding to the side effect burden [5,6], the second generation of DAAs have minimal side effects, are efficacious with shortened courses of treatment, and are associated with cure rates of more than 90% in phase II and III studies.

The initial observations with these DAA regimens in various real-world cohorts also show high SVR rates of 80%–90% but they are slightly lower than those seen in registration studies. For example, the first approved interferon-free regimens for treating genotype 2 and 3 infection included a combination of sofosbuvir (an NS5B inhibitor) and ribavirin for 12 to 24 weeks. This resulted in an SVR of 68%–90% [7,8,9,10]. DAA combinations currently recommended to treat genotype 3 infection include NS5B polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir and NS5A inhibitor daclatasvir with or without ribavirin while a combination of sofosbuvir and ribavirin is recommended for treatment of HCV genotype 2 infection, with possible addition of pegylated interferon alpha in patients with previous treatment failure. Other DAA combinations available to treat genotype 1 infection include sofosbuvir with either of the two NS5A inhibitors daclatasvir or ledispavir, a regimen consisting of ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir, and either dasbuvir or simeprevir with sofosbuvir. Treatment choice depends on HCV genotype, presence of cirrhosis, Child Pugh Class and previous HCV treatment experience. The above findings and extensive use of these drugs in the near future predicts that a proportion of patients will fail to achieve SVR and develop resistance.

HCV exists as a heterogeneous pool of genetic variants within an infected individual prior to treatment. This is due to the high error rate of HCV polymerase introducing on average one mutation per replicant and high rate of virion production [11,12]. Certain polymorphisms, which are resistant to direct acting antivirals, can exist at low levels prior to treatment and may get selected upon exposure to these drugs. In this review, we discuss DAAs according to their mechanism of action, drug resistance profiles, and discuss clinical applications where relevant.

2. Emergence of DAA Resistance

HCV has higher sequence diversity even within an individual genotype in comparison to other chronic viral infections such as hepatitis B virus or HIV [13]. HCV has a high turnover rate with an estimated half-life of only 2–5 h with 1010 to 1012 virions produced and cleared per day in an infected patient [11,14,15,16]. Because of lack of proof reading activity of HCV RNA dependent RNA polymerase (NS5B) [12,17] and high replication activity of HCV, a large number of viral variants are produced continuously during infection with an error rate of 10−3 to 10−4 mutations per nucleotide per genomic replication [17]. Most of these variants are cleared by the host immune system or are unable to replicate because of a functional loss in encoded proteins [18,19]. Thus a heterogeneous mixture of closely related genomes comprising a dominant strain (wild type strain) along with other strains present at lower frequencies makes up the HCV population in a given host. This pool of variants is termed the quasispecies in the host. This quasispecies existence of HCV in a given host results in a significant adaptation advantage because the simultaneous presence of multiple variant genomes allows for on-going evolutionary selection of mutations with better fitness to any given condition. A classic example of this is the adaptation of the quasispecies that occurs post-liver transplantation [20]. Hence, HCV variants with a different level of susceptibility may exist naturally at low levels in the absence of drug pressure and can be selected in patients with suboptimal response to treatment [21]. The biological and clinical implication of this selection is resistance to direct acting antiviral agents and treatment failure.

Relapse of HCV in patients who initially respond to DAA may be due to the replication of a residual variant that remained below the limit of detection at the end of treatment. Viral sequencing at the time of relapse may identify the virus sequence present at the end of treatment but it is also possible for viral population to evolve to wild type prior to sequencing after relapse, as it is not under selective pressure at the time.

4. Prevalence before and after Treatment with DAA

Under the selective pressure of DAAs, viruses with RAVs emerge that are undetectable prior to therapy. In a landmark study, Sarrazin et al [70] found that treatment with telaprevir resulted in the emergence of low-level resistance (V36A/M, T54A, R155K/T, A156S) and high-level resistance (A156V/T, 36 + 155, 33 + 156) RAVs with had frequencies inversely correlating with resistance. These variants were detectable using subcloning up to seven months after the cessation of therapy, implying that the minor variant may persist much longer. Similar RAVs were verified and revealed by applying similar methods for the other first-generation protease inhibitor, boceprevir, including V55A [71]. Approximately 50% of patients that fail treatment with boceprevir have detectable RAVs [32]. Next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis of a small number of individuals that repeatedly failed telaprevir treatment surprisingly did not have persistent RAVs present, but apparently independently experienced a de novo RAV generation upon treatment [72]. However the limitation of this study was 1% frequency, and recent evidence suggests that abundancies below 0.02% may be relevant for emergence of RAVs [73].Even in high-risk populations, treatment failure is more associated with the emergence of a pre-existing minority variant rather than reinfection [73].

A very recent analysis attempted to refine some of the NGS data detected at least low levels of susceptible or moderate resistance RAVs to second-generation protease inhibitor, simeprevir, in each patient analysed [74]. The prevalence of the common NS3 Q80K RAV that affects simeprevir efficacy is dependent on subtype and ethnic prevalence [75].

The most successful NS5B inhibitor in treatment now is sofosbuvir. Prior to full clinical development, the S282T RAV appeared to be problematic. However, this variant appears very rare [76,77]. Donaldson et al [74] performed an analysis on four phase III clinical trials in search of common RAVs against sofosbuvir, discovering L159F, C316N, and V321A were associated with virological failure [78]. Interestingly, this study also verified S282R mutation as associating with failure. It should be noted that the majority of patients with relapse had no clear resistance variants emerge, however there is the possibility that this is due to a lack of sensitivity in NGS technique.

NS5A RAVs can be very common, with Y93H detected in up to 15% of the population and L31M in up to 6.3% [79]. Other RAVs tend to also be fairly common detected in approximately 0.3%–3.5% of the population. Substitutions in genotype 1a include M28T, Q30R/H, L31V, and Y93R. Resistant variants persisted in the population beyond six months after treatment, revealing that these variants are well tolerated [80]. This represents a major challenge as most of the next-generation formulations include an NS5A inhibitor and there are some estimations that NS5A RAVs could persist indefinitely [53]. Recent compelling evidence shows that daclatasvir treatment of an NS5A inhibitor resistant variant in combination with an analogue of daclatasvir, dramatically enhances the resistance barrier [54]. This is due to communication between NS5A molecules resulting in allosteric differences in inhibitor binding. Table 1 summarises the data for most prevalent resistance associated variants and drug class.

Table 1.

Common RAVs; resistance and prevalence.

| Drug Class | Example | Common RAV | Resistance | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS3/4A inhibitor | telaprevir | V36M | low | <1% |

| boceprevir | T54S/A | low | 2%–3% | |

| simeprevir | V55A | low | 0.4%–3% | |

| asunaprevir | Q80K | low | 0.5%–75% | |

| faldaprevir | R155K | high | <1% | |

| NS5A inhibitor | daclatasvir | M28 | high | 0.5%–4% |

| ombitasvir | Q30 | high | 0.3%–1.3% (geno 1) 50%–100% (geno 3,4) | |

| ledipasvir | L31V | high | 0.9%–6.3% (geno 1) 74%–100%(geno 2,4) | |

| Y93H | high | 1.5%–14% | ||

| NS5B NPI | sofosbuvir | L159F | n.d. | 5.2% |

| V321A | n.d. | 2.2% | ||

| S282R | low | 0.4% | ||

| NS5B NNPI | dasabuvir | C316N | low | 11%–36% |

Data was summarised and collated for the most prevalent RAVs [78,79,81,82]. n.d.: no data.

5. Clinical Significance of Baseline RAVs

In sofosbuvir trials, while there were variants that emerged and were statistically significant with resistance, the majority of subjects that experienced relapse did not carry identifiable RAVs [78]. For other drug classes, the emergence of resistant variants may be derived from a very small proportion of the quasispecies that can only be detected with NGS, accompanied with costly analysis. Our current understanding of the breadth and strength of resistance, in combination with contributing host responses make response prediction based on sequence analysis untenable [83]. At this time, data need to be collected on all of these classes of drugs and the next-generation of agents in various combinations for comprehensive understanding of how to minimize or ablate breakthrough mutations.

6. Conclusions

HCV drug resistance is an important and upcoming clinical issue in the context of limited data and a large number of DAA in development or approved for clinical use. Understanding the position and mechanism of resistance may result in engineered antiviral cocktails that are highly efficacious and minimize side-effects. The relevance of pre-existing resistance mutations for response to DAAs needs to be better studied in order to understand their significance in selective tailoring of various DAA for personalized care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Plymouth University Peninsula School of Medicine and Dentistry Hepatology Research Group for publication costs.

Author Contributions

Asma Ahmed wrote the manuscript and generated the figure; Daniel J. Felmlee wrote and edited the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mohd Hanafiah, K.; Groeger, J.; Flaxman, A.D.; Wiersma, S.T. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: New estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, J.P.; Humphreys, I.; Flaxman, A.; Brown, A.; Cooke, G.S.; Pybus, O.G.; Barnes, E. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology 2015, 61, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Hepatitis C. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/ (accessed on 29 September 2015).

- Lauer, G.M.; Walker, B.D. Hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, I.M.; McHutchison, J.G.; Dusheiko, G.; di Bisceglie, A.M.; Reddy, K.R.; Bzowej, N.H.; Marcellin, P.; Muir, A.J.; Ferenci, P.; Flisiak, R.; et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2405–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poordad, F.; McCone, J., Jr.; Bacon, B.R.; Bruno, S.; Manns, M.P.; Sulkowski, M.S.; Jacobson, I.M.; Reddy, K.R.; Goodman, Z.D.; Boparai, N.; et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawitz, E.; Mangia, A.; Wyles, D.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.; Hassanein, T.; Gordon, S.C.; Schultz, M.; Davis, M.N.; Kayali, Z.; Reddy, K.R.; et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1878–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, I.M.; Gordon, S.C.; Kowdley, K.V.; Yoshida, E.M.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.; Sulkowski, M.S.; Shiffman, M.L.; Lawitz, E.; Everson, G.; Bennett, M.; et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeuzem, S.; Dusheiko, G.M.; Salupere, R.; Mangia, A.; Flisiak, R.; Hyland, R.H.; Illeperuma, A.; Svarovskaia, E.; Brainard, D.M.; Symonds, W.T.; et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin in HCV genotypes 2 and 3. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1993–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, G.R.; Pianko, S.; Brown, A.; Forton, D.; Nahass, R.G.; George, J.; Barnes, E.; Brainard, D.M.; Massetto, B.; Lin, M.; et al. Efficacy of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin with or without peginterferon-α in patients with HCV genotype 3 infection and treatment-experienced patients with cirrhosis and HCV genotype 2 infection. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, A.U.; Lam, N.P.; Dahari, H.; Gretch, D.R.; Wiley, T.E.; Layden, T.J.; Perelson, A.S. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-α therapy. Science 1998, 282, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, N.; Alter, H.J.; Miller, R.H.; Purcell, R.H. Nucleotide sequence and mutation rate of the H strain of hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 3392–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, S.; Thomas, D. Hepatitis C: Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 7th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, E.; Neumann, A.U.; Schmidt, J.M.; Zeuzem, S. Hepatitis C virus kinetics. Antivir. Ther. 2000, 5, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.; Spindler, K.; Horodyski, F.; Grabau, E.; Nichol, S.; VandePol, S. Rapid evolution of RNA genomes. Science 1982, 215, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martell, M.; Esteban, J.I.; Quer, J.; Genesca, J.; Weiner, A.; Esteban, R.; Guardia, J.; Gomez, J. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) circulates as a population of different but closely related genomes: Quasispecies nature of HCV genome distribution. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 3225–3229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bartenschlager, R.; Lohmann, V. Replication of hepatitis C virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81, 1631–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregori, J.; Esteban, J.I.; Cubero, M.; Garcia-Cehic, D.; Perales, C.; Casillas, R.; Alvarez-Tejado, M.; Rodriguez-Frias, F.; Guardia, J.; Domingo, E.; et al. Ultra-deep pyrosequencing (UDPS) data treatment to study amplicon HCV minor variants. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermehren, J.; Sarrazin, C. The role of resistance in HCV treatment. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 26, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fafi-Kremer, S.; Fofana, I.; Soulier, E.; Carolla, P.; Meuleman, P.; Leroux-Roels, G.; Patel, A.H.; Cosset, F.L.; Pessaux, P.; Doffoel, M.; et al. Viral entry and escape from antibody-mediated neutralization influence hepatitis C virus reinfection in liver transplantation. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 2019–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieffer, T.L.; Kwong, A.D.; Picchio, G.R. Viral resistance to specifically targeted antiviral therapies for hepatitis C (STAT-Cs). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pockros, P.J. New direct-acting antivirals in the development for hepatitis C virus infection. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2010, 3, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foy, E.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Sumpter, R., Jr.; Ikeda, M.; Lemon, S.M.; Gale, M., Jr. Regulation of interferon regulatory factor-3 by the hepatitis C virus serine protease. Science 2003, 300, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Foy, E.; Ferreon, J.C.; Nakamura, M.; Ferreon, A.C.; Ikeda, M.; Ray, S.C.; Gale, M., Jr.; Lemon, S.M. Immune evasion by hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease-mediated cleavage of the toll-like receptor 3 adaptor protein TRIF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 2992–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, G.; Zhong, J.; Chisari, F.V. Inhibition of dsRNA-induced signaling in hepatitis C virus-infected cells by NS3 protease-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8499–8504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrazin, C.; Zeuzem, S. Resistance to direct antiviral agents in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieffer, T.L.; de Meyer, S.; Bartels, D.J.; Sullivan, J.C.; Zhang, E.Z.; Tigges, A.; Dierynck, I.; Spanks, J.; Dorrian, J.; Jiang, M.; et al. Hepatitis C viral evolution in genotype 1 treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients receiving telaprevir-based therapy in clinical trials. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogert, R.A.; Howe, J.A.; Vierling, J.M.; Kwo, P.Y.; Lawitz, E.J.; McCone, J.; Schiff, E.R.; Pound, D.; Davis, M.N.; Gordon, S.C.; et al. Resistance-associated amino acid variants associated with boceprevir plus pegylated interferon-α2b and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C in the sprint-1 trial. Antivir. Ther. 2013, 18, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halfon, P.; Locarnini, S. Hepatitis C virus resistance to protease inhibitors. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntzen, T.; Timm, J.; Berical, A.; Lennon, N.; Berlin, A.M.; Young, S.K.; Lee, B.; Heckerman, D.; Carlson, J.; Reyor, L.L.; et al. Naturally occurring dominant resistance mutations to hepatitis C virus protease and polymerase inhibitors in treatment-naive patients. Hepatology 2008, 48, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierynck, I.; Ghys, A.; Witek, J.; Luo, D.; Janssen, K.; Daems, B.; Picchio, G.; Buti, M.; De Meyer, S. Incidence of virological failure and emergence of resistance with twice-daily vs every 8-h administration of telaprevir in the optimize study. J. Viral Hepat. 2014, 21, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, R.J.; Howe, J.A.; Ogert, R.A.; Zeuzem, S.; Poordad, F.; Gordon, S.C.; Ralston, R.; Tong, X.; Sniukiene, V.; Strizki, J.; et al. Analysis of boceprevir resistance associated amino acid variants (RAVs) in two phase 3 boceprevir clinical studies. Virology 2013, 444, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeuzem, S.; Sulkowski, M.; Zoulim, F.; Sherman, K.; Alberti, A.; Wei, L.; van Baelen, B.; Sullivan, J.; Kieffer, T.; de Meyer, S.; et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with telaprevir in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a and rabivirin: Interim analysis of extend study. Hepatology 2010, 52, 436A. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, X.V.; de Bruijne, J.; Sullivan, J.C.; Kieffer, T.L.; Ho, C.K.; Rebers, S.P.; de Vries, M.; Reesink, H.W.; Weegink, C.J.; Molenkamp, R.; et al. Evaluation of persistence of resistant variants with ultra-deep pyrosequencing in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with telaprevir. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, O.; Verbinnen, T.; Fevery, B.; Tambuyzer, L.; Vijgen, L.; Peeters, M.; Buelens, A.; Ceulemans, H.; Beumont, M.; Picchio, G.; et al. Virology analyses of HCV isolates from genotype 1-infected patients treated with simeprevir plus peginterferon/ribavirin in phase IIb/III studies. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, A.; Sun, S.C.; Qi, X.; Chen, X.; Ku, K.; Worth, A.; Wong, K.A.; Harris, J.; Miller, M.D.; Mo, H. Susceptibility of treatment-naive hepatitis C virus (HCV) clinical isolates to HCV protease inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 5288–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhee, F.; Friborg, J.; Levine, S.; Chen, C.; Falk, P.; Yu, F.; Hernandez, D.; Lee, M.S.; Chaniewski, S.; Sheaffer, A.K.; et al. Resistance analysis of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease inhibitor asunaprevir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3670–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manns, M.; Marcellin, P.; Poordad, F.; de Araujo, E.S.; Buti, M.; Horsmans, Y.; Janczewska, E.; Villamil, F.; Scott, J.; Peeters, M.; et al. Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a or 2b plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-2): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet (Lond. Engl.) 2014, 384, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawitz, E.; Poordad, F.; Gutierrez, J.; Kakuda, T.; Picchio, G.; Beets, G.; Vandevoorde, A.; Peter, V.R.; Jaquesmyn, B.; Quinn, G.; et al. SVR 12 results from the phase II, open-label impact study of simeprevir (SMV) in combination with daclatasvir (DCV) and sofosbuvir (SOF) in treatment naive and experienced patients with chronic HCV genotype 1/4 infection and decompensated liver disease. Hepatology 2015, 62, 227A. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlotsky, J.M. NS5A inhibitors in the treatment of hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGivern, D.R.; Masaki, T.; Williford, S.; Ingravallo, P.; Feng, Z.; Lahser, F.; Asante-Appiah, E.; Neddermann, P.; de Francesco, R.; Howe, A.Y.; et al. Kinetic analyses reveal potent and early blockade of hepatitis C virus assembly by NS5A inhibitors. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, C.; Romero-Brey, I.; Radujkovic, D.; Terreux, R.; Zayas, M.; Paul, D.; Harak, C.; Hoppe, S.; Gao, M.; Penin, F.; et al. Daclatasvir-like inhibitors of NS5A block early biogenesis of hepatitis C virus-induced membranous replication factories, independent of RNA replication. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellinghuisen, T.L.; Marcotrigiano, J.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Rice, C.M. The NS5A protein of hepatitis C virus is a zinc metalloprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 48576–48587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukkapalli, V.; Berger, K.L.; Kelly, S.M.; Thomas, M.; Deiters, A.; Randall, G. Daclatasvir inhibits hepatitis C virus NS5A motility and hyper-accumulation of phosphoinositides. Virology 2015, 476, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reghellin, V.; Donnici, L.; Fenu, S.; Berno, V.; Calabrese, V.; Pagani, M.; Abrignani, S.; Peri, F.; de Francesco, R.; Neddermann, P. NS5A inhibitors impair NS5A-phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase iiialpha complex formation and cause a decrease of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate and cholesterol levels in hepatitis C virus-associated membranes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 7128–7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulkowski, M.S.; Gardiner, D.F.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.; Reddy, K.R.; Hassanein, T.; Jacobson, I.; Lawitz, E.; Lok, A.S.; Hinestrosa, F.; Thuluvath, P.J.; et al. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridell, R.A.; Wang, C.; Sun, J.H.; O’Boyle, D.R., 2nd; Nower, P.; Valera, L.; Qiu, D.; Roberts, S.; Huang, X.; Kienzle, B.; et al. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of variants resistant to hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A replication complex inhibitor BMS-790052 in humans: In vitro and in vivo correlations. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1924–1935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dore, G.J.; Lawitz, E.; Hezode, C.; Shafran, S.; Ramji, A.; Tatum, H.; Taliani, G.; Tran, A.; Brunetto, M.; Zaltron, S.; et al. Daclatasvir combined with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for 12 or 16 weeks in patients with HCV genotype 1 or 3 infection: Command GT2/3 study. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, S570–S571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, F.; Hernandez, D.; Yu, F.; Ueland, J.; Monikowski, A.; Carifa, A.; Falk, P.; Wang, C.; Fridell, R.; Eley, T.; et al. Resistance analysis of hepatitis C virus genotype 1 prior treatment null responders receiving daclatasvir and asunaprevir. Hepatology 2013, 58, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeuzem, S.; Mizokami, M.; Pianko, S.; Mangia, A.; Han, K.; Martin, R.; Svarovskaia, E.; Dvory-Sobol, H.; Doehle, B.; Pang, P.; et al. Prevalence of pre-treatment NS5A resistance associated variants in genotype 1 patients across different regions using deep sequencing and effect on treatment outcome with LDV/SOF. Hepatology 2015, 62, 254A. [Google Scholar]

- Peiffer, K.H.; Sommer, L.; Susser, S.; Vermehren, J.; Herrmann, E.; Doring, M.; Dietz, J.; Perner, D.; Berkowski, C.; Zeuzem, S.; et al. IFN λ 4 genotypes and resistance-associated variants in HCV genotype 1 and 3 infected patients. Hepatology 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.R.; Cooper, J.N.; Lalezari, J.P.; Lawitz, E.; Pockros, P.J.; Gitlin, N.; Freilich, B.F.; Younes, Z.H.; Harlan, W.; Ghalib, R.; et al. All-oral 12-week treatment with daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection: Ally-3 phase III study. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlotsky, J.M. Therapy: Avoiding treatment failures associated with HCV resistance. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 673–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.H.; O’Boyle, D.R., 2nd; Fridell, R.A.; Langley, D.R.; Wang, C.; Roberts, S.B.; Nower, P.; Johnson, B.M.; Moulin, F.; Nophsker, M.J.; et al. Resensitizing daclatasvir-resistant hepatitis C variants by allosteric modulation of NS5A. Nature 2015, 527, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjith-Kumar, C.; Kao, C. Biochemical Activities of the HCV NS5B RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase; Taylor & Francis: Wymondham, England, 2006; pp. 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lontok, E.; Harrington, P.; Howe, A.; Kieffer, T.; Lennerstrand, J.; Lenz, O.; McPhee, F.; Mo, H.; Parkin, N.; Pilot-Matias, T.; et al. Hepatitis C virus drug resistance-associated substitutions: State of the art summary. Hepatology 2015, 62, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, A.M.; Espiritu, C.; Bansal, S.; Micolochick Steuer, H.M.; Niu, C.; Zennou, V.; Keilman, M.; Zhu, Y.; Lan, S.; Otto, M.J.; et al. Genotype and subtype profiling of PSI-7977 as a nucleotide inhibitor of hepatitis C virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3359–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svarovskaia, E.S.; Dvory-Sobol, H.; Parkin, N.; Hebner, C.; Gontcharova, V.; Martin, R.; Ouyang, W.; Han, B.; Xu, S.; Ku, K.; et al. Infrequent development of resistance in genotype 1–6 hepatitis C virus-infected subjects treated with sofosbuvir in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gane, E.J.; Stedman, C.A.; Hyland, R.H.; Ding, X.; Svarovskaia, E.; Symonds, W.T.; Hindes, R.G.; Berrey, M.M. Nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osinusi, A.; Meissner, E.G.; Lee, Y.J.; Bon, D.; Heytens, L.; Nelson, A.; Sneller, M.; Kohli, A.; Barrett, L.; Proschan, M.; et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C genotype 1 in patients with unfavorable treatment characteristics: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013, 310, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gane, E.; Abergel, A.; Metivier, S.; Nahass, R.; Ryan, M.; Stedman, C.A.; Svarovskaia, E.; M, H.; Doehle, B.; Dvory-Sobol, H.; et al. The emergence of NS5B resistant associated variant S282T after sofosbuvir based treatment. Hepatology 2015, 62, 322 A. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, L.; Welzel, T.M.; Zeuzem, S. New therapeutic strategies in HCV: Polymerase inhibitors. Liver Int.: Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2013, 33, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kati, W.; Koev, G.; Irvin, M.; Beyer, J.; Liu, Y.; Krishnan, P.; Reisch, T.; Mondal, R.; Wagner, R.; Molla, A.; et al. In vitro activity and resistance profile of dasabuvir, a nonnucleoside hepatitis C virus polymerase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1505–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowdley, K.V.; Lawitz, E.; Poordad, F.; Cohen, D.E.; Nelson, D.R.; Zeuzem, S.; Everson, G.T.; Kwo, P.; Foster, G.R.; Sulkowski, M.S.; et al. Phase 2b trial of interferon-free therapy for hepatitis C virus genotype 1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feld, J.J.; Kowdley, K.V.; Coakley, E.; Sigal, S.; Nelson, D.R.; Crawford, D.; Weiland, O.; Aguilar, H.; Xiong, J.; Pilot-Matias, T.; et al. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1594–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeuzem, S.; Jacobson, I.M.; Baykal, T.; Marinho, R.T.; Poordad, F.; Bourliere, M.; Sulkowski, M.S.; Wedemeyer, H.; Tam, E.; Desmond, P.; et al. Retreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1604–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferenci, P.; Bernstein, D.; Lalezari, J.; Cohen, D.; Luo, Y.; Cooper, C.; Tam, E.; Marinho, R.T.; Tsai, N.; Nyberg, A.; et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1983–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreone, P.; Colombo, M.G.; Enejosa, J.V.; Koksal, I.; Ferenci, P.; Maieron, A.; Mullhaupt, B.; Horsmans, Y.; Weiland, O.; Reesink, H.W.; et al. ABT-450, ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir achieves 97% and 100% sustained virologic response with or without ribavirin in treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype 1b infection. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fevery, B.; Thys, K.; Van Rossem, E.; Verbinnen, T.; Picchio, G.; Aerssens, J.; De Meyer, S.; Beumont, M.; Kerland, D.; Lenz, O. Deep Sequencing Analysis in HCV Genotype 1 Infected Patients Treated with Simeprevir Plus Sofosbuvir with/withour Ribavirin in the Cosmos Study; EASL: Vienna, Austria, 2015; p. P0780. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin, C.; Kieffer, T.L.; Bartels, D.; Hanzelka, B.; Muh, U.; Welker, M.; Wincheringer, D.; Zhou, Y.; Chu, H.M.; Lin, C.; et al. Dynamic hepatitis C virus genotypic and phenotypic changes in patients treated with the protease inhibitor telaprevir. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1767–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susser, S.; Welsch, C.; Wang, Y.; Zettler, M.; Domingues, F.S.; Karey, U.; Hughes, E.; Ralston, R.; Tong, X.; Herrmann, E.; et al. Characterization of resistance to the protease inhibitor boceprevir in hepatitis C virus-infected patients. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susser, S.; Flinders, M.; Reesink, H.W.; Zeuzem, S.; Lawyer, G.; Ghys, A.; van Eygen, V.; Witek, J.; de Meyer, S.; Sarrazin, C. Evolution of hepatitis C virus quasispecies during repeated treatment with the ns3/4a protease inhibitor telaprevir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 2746–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Abdelrahman, T.; Hughes, J.; Main, J.; McLauchlan, J.; Thursz, M.; Thomson, E. Next-generation sequencing sheds light on the natural history of hepatitis C infection in patients who fail treatment. Hepatology 2015, 61, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogishi, M.; Yotsuyanagi, H.; Tsutsumi, T.; Gatanaga, H.; Ode, H.; Sugiura, W.; Moriya, K.; Oka, S.; Kimura, S.; Koike, K. Deconvoluting the composition of low-frequency hepatitis C viral quasispecies: Comparison of genotypes and NS3 resistance-associated variants between HCV/HIV coinfected hemophiliacs and HCV monoinfected patients in Japan. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrazin, C.; Lathouwers, E.; Peeters, M.; Daems, B.; Buelens, A.; Witek, J.; Wyckmans, Y.; Fevery, B.; Verbinnen, T.; Ghys, A.; et al. Prevalence of the hepatitis C virus NS3 polymorphism Q80K in genotype 1 patients in the european region. Antivir. Res. 2015, 116, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, A.; Spada, E.; Equestre, M.; Bruni, R.; Tritarelli, E.; Coppola, N.; Sagnelli, C.; Sagnelli, E.; Ciccaglione, A.R. Naturally occurring mutations associated with resistance to HCV NS5B polymerase and ns3 protease inhibitors in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C. Virol. J. 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margeridon-Thermet, S.; le Pogam, S.; Li, L.; Liu, T.F.; Shulman, N.; Shafer, R.W.; Najera, I. Similar prevalence of low-abundance drug-resistant variants in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1a and 1b hepatitis C virus infections as determined by ultradeep pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, E.F.; Harrington, P.R.; O’Rear, J.J.; Naeger, L.K. Clinical evidence and bioinformatics characterization of potential hepatitis C virus resistance pathways for sofosbuvir. Hepatology 2015, 61, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrazin, C. The importance of resistance to direct antiviral drugs in HCV infection in clinical practice. J. Hepatol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Sun, J.H.; O’Boyle, D.R., 2nd; Nower, P.; Valera, L.; Roberts, S.; Fridell, R.A.; Gao, M. Persistence of resistant variants in hepatitis C virus-infected patients treated with the NS5A replication complex inhibitor daclatasvir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2054–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, R.; Queiroz, A.T.; Pessoa, M.G.; da Silva, E.F.; Mazo, D.F.; Carrilho, F.J.; Carvalho-Filho, R.J.; de Carvalho, I.M. The presence of resistance mutations to protease and polymerase inhibitors in hepatitis C virus sequences from the Los Alamos databank. J. Viral Hepat. 2013, 20, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieffer, T.L.; George, S. Resistance to hepatitis C virus protease inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014, 8, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.D.; Sarrazin, C. Antiviral therapy of hepatitis C in 2014: Do we need resistance testing? Antivir. Res. 2014, 105, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).