Structural and Functional Comparisons of Retroviral Envelope Protein C-Terminal Domains: Still Much to Learn

Abstract

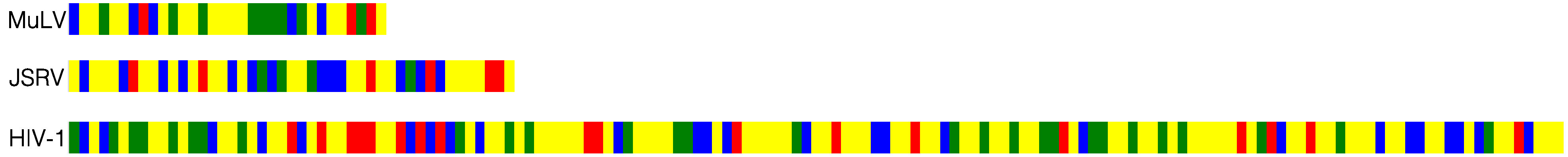

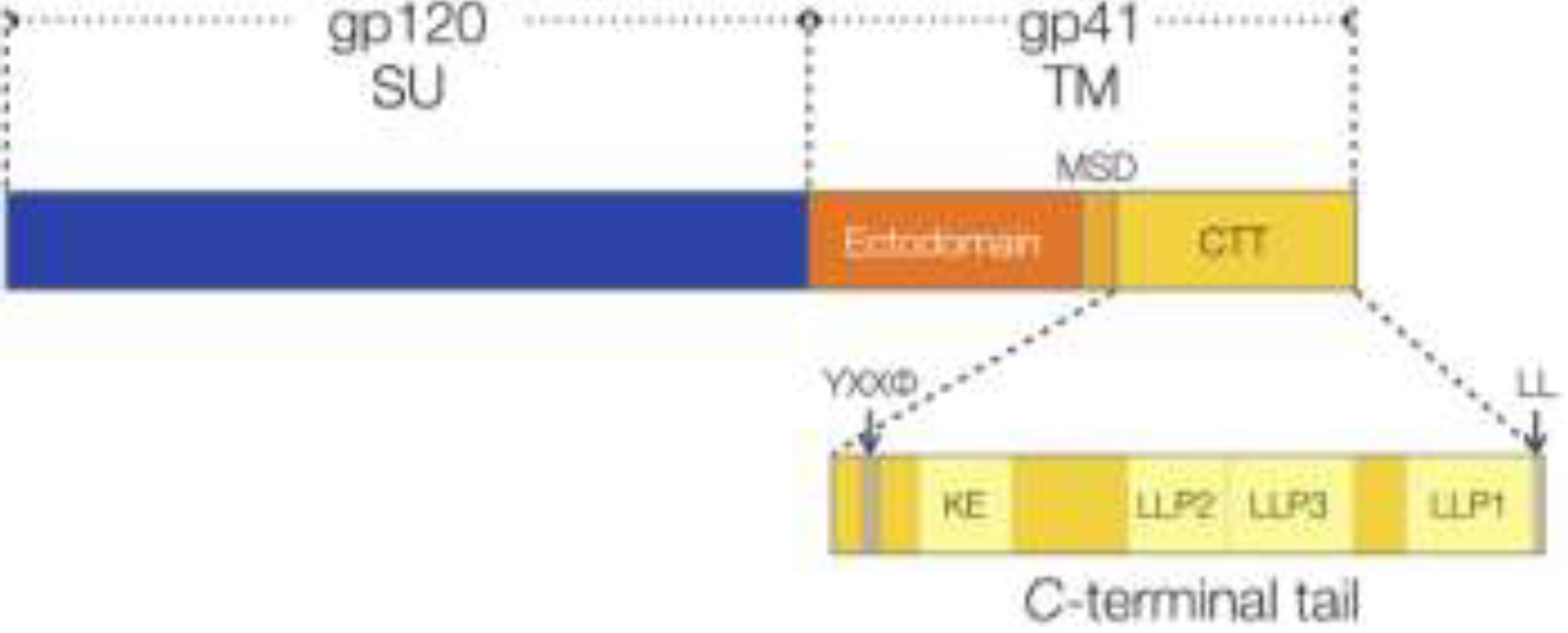

:1. Introduction

3. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Authors’ Contribution

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Checkley, M.A.; Luttge, B.G.; Freed, E.O. HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein biosynthesis, trafficking, and incorporation. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 582–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffar, O.K.; Dowbenko, D.J.; Berman, P.W. Topogenic analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein, gp160, in microsomal membranes. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 107, 1677–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollier, M.J.; Dimmock, N.J. The C-terminal tail of the gp41 transmembrane envelope glycoprotein of HIV-1 clades A, B, C, and D may exist in two conformations: An analysis of sequence, structure, and function. Virology 2005, 337, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckbeck, J.D.; Sun, C.; Sturgeon, T.J.; Montelaro, R.C. Detailed topology mapping reveals substantial exposure of the “cytoplasmic” C-terminal tail (CTT) sequences in HIV-1 Env proteins at the cell surface. PLoS One 2013, 8, e65220. [Google Scholar]

- Steckbeck, J.D.; Sun, C.; Sturgeon, T.J.; Montelaro, R.C. Topology of the C-terminal tail of HIV-1 gp41: Differential exposure of the Kennedy epitope on cell and viral membranes. PLoS One 2010, 5, e15261. [Google Scholar]

- Postler, T.S.; Martinez-Navio, J.M.; Yuste, E.; Desrosiers, R.C. Evidence against extracellular exposure of a highly immunogenic region in the C-terminal domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus gp41 transmembrane protein. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Kondo, N.; Long, Y.; Xiao, D.; Iwamoto, A.; Matsuda, Z. Membrane topology analysis of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp41. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckbeck, J.D.; Kuhlmann, A.-S.; Montelaro, R.C. C-terminal tail of human immunodeficiency virus gp41: Functionally rich and structurally enigmatic. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postler, T.S.; Desrosiers, R.C. The tale of the long tail: The cytoplasmic domain of HIV-1 gp41. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.S.; Mulinge, M.; Bercoff, D.P. The frantic play of the concealed HIV envelope cytoplasmic tail. Retrovirology 2013, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, J.B. The rodent leukemias: Virus-induced murine leukemias. Annu. Rev. Med. 1964, 15, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Putten, H.; Quint, W.; van Raaij, J.; Maandag, E.R.; Verma, I.M.; Berns, A. M-MuLV-induced leukemogenesis: Integration and structure of recombinant proviruses in tumors. Cell 1981, 24, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.; Shinnick, T.M.; Witte, O.; Ponticelli, A.; Sutcliffe, J.G.; Lerner, R.A. Sequence-specific antibodies show that maturation of Moloney leukemia virus envelope polyprotein involves removal of a COOH-terminal peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 6023–6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, J.A.; Anderson, W.F. pH-Independent murine leukemia virus ecotropic envelope-mediated cell fusion: Implications for the role of the R peptide and p12E TM in viral entry. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 3220–3231. [Google Scholar]

- Ragheb, J.A.; Anderson, W.F. Uncoupled expression of Moloney murine leukemia virus envelope polypeptides SU and TM: A functional analysis of the role of TM domains in viral entry. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 3207–3219. [Google Scholar]

- Rein, A.; Mirro, J.; Haynes, J.G.; Ernst, S.M.; Nagashima, K. Function of the cytoplasmic domain of a retroviral transmembrane protein: p15E-p2E Cleavage activates the membrane fusion capability of the murine leukemia virus Env protein. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 1773–1781. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Compans, R.W. Analysis of the cell fusion activities of chimeric simian immunodeficiency virus-murine leukemia virus envelope proteins: Inhibitory effects of the R peptide. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Li, Z.-N.; Yao, Q.; Yang, C.; Steinhauer, D.A.; Compans, R.W. Murine leukemia virus R peptide inhibits influenza virus hemagglutinin-induced membrane fusion. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 6106–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Compans, R.W. Analysis of the murine leukemia virus R peptide: Delineation of the molecular determinants which are important for its fusion inhibition activity. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 8490–8496. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Yang, C.; Compans, R.W. Mutations in the cytoplasmic tail of murine leukemia virus envelope protein suppress fusion inhibition by R peptide. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 2337–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löving, R.; Wu, S.-R.; Sjöberg, M.; Lindqvist, B.; Garoff, H. Maturation cleavage of the murine leukemia virus Env precursor separates the transmembrane subunits to prime it for receptor triggering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7735–7740. [Google Scholar]

- Leroux, C.; Girard, N.; Cottin, V.; Greenland, T.; Mornex, J.-F.; Archer, F. Jaagsiekte Sheep Retrovirus (JSRV): From virus to lung cancer in sheep. Vet. Res. 2007, 38, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-L.; Miller, A.D. Oncogenic transformation by the jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus envelope protein. Oncogene 2007, 26, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmarini, M.; Fan, H. Molecular biology of jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003, 275, 81–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati, S.; Pittau, M.; Alberti, A.; Pozzi, S.; York, D.F.; Sharp, J.M.; Palmarini, M. An accessory open reading frame (ORF-x) of jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus is conserved between different virus isolates. Virus Res. 2000, 66, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmarini, M.; Sharp, J.M.; de las Heras, M.; Fan, H. Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus is necessary and sufficient to induce a contagious lung cancer in sheep. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 6964–6972. [Google Scholar]

- Wootton, S.K.; Halbert, C.L.; Miller, A.D. Sheep retrovirus structural protein induces lung tumours. Nature 2005, 434, 904–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, M.; Cousens, C.; Centorame, P.; Pinoni, C.; de las Heras, M.; Palmarini, M. Expression of the jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to induce lung tumors in sheep. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 8030–8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-L.; Duh, F.-M.; Lerman, M.I.; Miller, A.D. Role of virus receptor Hyal2 in oncogenic transformation of rodent fibroblasts by sheep betaretrovirus env proteins. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 2850–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilkovitch-Miagkova, A.; Duh, F.-M.; Kuzmin, I.; Angeloni, D.; Liu, S.-L.; Miller, A.D.; Lerman, M.I. Hyaluronidase 2 negatively regulates RON receptor tyrosine kinase and mediates transformation of epithelial cells by jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4580–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songyang, Z.; Shoelson, S.E.; Chaudhuri, M.; Gish, G.; Pawson, T.; Haser, W.G.; King, F.; Roberts, T.; Ratnofsky, S.; Lechleider, R.J. SH2 domains recognize specific phosphopeptide sequences. Cell 1993, 72, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, M.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Albritton, L.M.; Liu, S.-L. Fusogenicity of Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus envelope protein is dependent on low pH and is enhanced by cytoplasmic tail truncations. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 2543–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushlow, K.; Olsen, K.; Stiegler, G.; Payne, S.L.; Montelaro, R.C.; Issel, C.J. Lentivirus genomic organization: The complete nucleotide sequence of the env gene region of equine infectious anemia virus. Virology 1986, 155, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shacklett, B.L.; Weber, C.J.; Shaw, K.E.; Keddie, E.M.; Gardner, M.B.; Sonigo, P.; Luciw, P.A. The intracytoplasmic domain of the Env transmembrane protein is a locus for attenuation of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 5836–5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, L.; Emerman, M.; Tiollais, P.; Sonigo, P. The cytoplasmic domain of simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane protein modulates infectivity. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 4395–4403. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, V.M.; Edmondson, P.; Murphey-Corb, M.; Arbeille, B.; Johnson, P.R.; Mullins, J.I. SIV adaptation to human cells. Nature 1989, 341, 573–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, T.; Wooley, D.P.; Naidu, Y.M.; Kestler, H.W.; Daniel, M.D.; Li, Y.; Desrosiers, R.C. Significance of premature stop codons in env of Simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 4709–4714. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, D.; Wesson, M. The most highly amphiphilic alpha-helices include two amino acid segments in human immunodeficiency virus glycoprotein 41. Biopolymers 1990, 29, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Garry, R.F.; Jaynes, J.M.; Montelaro, R.C. A structural correlation between lentivirus transmembrane proteins and natural cytolytic peptides. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1991, 7, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Cloyd, M.W.; Liebmann, J.; Rinaldo, C.R.; Islam, K.R.; Wang, S.Z.; Mietzner, T.A.; Montelaro, R.C. Alterations in cell membrane permeability by the lentivirus lytic peptide (LLP-1) of HIV-1 transmembrane protein. Virology 1993, 196, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernomordik, L.; Chanturiya, A.N.; Suss-Toby, E.; Nora, E.; Zimmerberg, J. An amphipathic peptide from the C-terminal region of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein causes pore formation in membranes. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 7115–7123. [Google Scholar]

- Kliger, Y.; Shai, Y. A leucine zipper-like sequence from the cytoplasmic tail of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein binds and perturbs lipid bilayers. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 5157–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, S.K.; Srinivas, R.V.; Anantharamaiah, G.M.; Segrest, J.P.; Compans, R.W. Membrane interactions of synthetic peptides corresponding to amphipathic helical segments of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 envelope glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 7121–7127. [Google Scholar]

- Steckbeck, J.D.; Craigo, J.K.; Barnes, C.O.; Montelaro, R.C. Highly conserved structural properties of the C-terminal tail of HIV-1 gp41 protein despite substantial sequence variation among diverse clades: Implications for functions in viral replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 27156–27166. [Google Scholar]

- Boscia, A.L.; Akabori, K.; Benamram, Z.; Michel, J.A.; Jablin, M.S.; Steckbeck, J.D.; Montelaro, R.C.; Nagle, J.F.; Tristram-Nagle, S. Membrane Structure correlates to function of LLP2 on the cytoplasmic tail of HIV-1 gp41 protein. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, G.; Horvath, S.; Woodward, S.; Eiserling, F.; Eisenberg, D. A molecular model for membrane fusion based on solution studies of an amphiphilic peptide from HIV gp41. Protein Sci. 1992, 1, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Schwarz, E.; Komaromy, M.; Wall, R. Analysis of membrane and surface protein sequences with the hydrophobic moment plot. J. Mol. Biol. 1984, 179, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, P.; Templer, R.; Meijberg, W.; Allen, S.; Curran, A.; Lorch, M. In vitro studies of membrane protein folding. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001, 36, 501–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, R.S. Lateral pressures in cell membranes: A mechanism for modulation of protein function. J. Phys. Chem. 1997, 101, 1723–1725. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, R.S. Lipid composition and the lateral pressure profile in bilayers. Biophys. J. 1999, 76, 2625–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, R.S. The influence of membrane lateral pressures on simple geometric models of protein conformational equilibria. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1999, 101, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, T.S.; Cascio, M. Effects of membrane lipids on ion channel structure and function. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2003, 38, 161–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink-van der Laan, E.; Killian, J.A.; de Kruijff, B. Nonbilayer lipids affect peripheral and integral membrane proteins via changes in the lateral pressure profile. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1666, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.; Sarkar, S.; Gupta, P.; Montelaro, R.C. Antibody neutralization escape mediated by point mutations in the intracytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, R.S. Size distribution of barrel-stave aggregates of membrane peptides: Influence of the bilayer lateral pressure profile. Biophys. J. 2002, 82, 2520–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D. Lateral pressure profile, spontaneous curvature frustration, and the incorporation and conformation of proteins in membranes. Biophys. J. 2007, 93, 3884–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner, A.S.; Willis, J.R.; Crowe, J.E.; Aiken, C. Maturation-induced cloaking of neutralization epitopes on HIV-1 particles. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.A.; Bartesaghi, A.; Borgnia, M.J.; Meyerson, J.R.; de la Cruz, M.J.V.; Bess, J.W.; Nandwani, R.; Hoxie, J.A.; Lifson, J.D.; Milne, J.L.S.; et al. Molecular architectures of trimeric SIV and HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins on intact viruses: Strain-dependent variation in quaternary structure. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Y.-H. Surface exposure of the HIV-1 env cytoplasmic tail LLP2 domain during the membrane fusion process: Interaction with gp41 fusion core. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 16723–16731. [Google Scholar]

- Futaki, S. Membrane-permeable arginine-rich peptides and the translocation mechanisms. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.J.; Kim, D.T.; Steinman, L.; Fathman, C.G.; Rothbard, J.B. Polyarginine enters cells more efficiently than other polycationic homopolymers. J. Pept. Res. 2000, 56, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, C.-H.; Weissleder, R. Arginine containing peptides as delivery vectors. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2003, 55, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inomata, K.; Ohno, A.; Tochio, H.; Isogai, S.; Tenno, T.; Nakase, I.; Takeuchi, T.; Futaki, S.; Ito, Y.; Hiroaki, H.; Shirakawa, M. High-resolution multi-dimensional NMR spectroscopy of proteins in human cells. Nature 2009, 458, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, E.O.; Martin, M.A. Virion incorporation of envelope glycoproteins with long but not short cytoplasmic tails is blocked by specific, single amino acid substitutions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 1984–1989. [Google Scholar]

- Freed, E.O.; Martin, M.A. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Aiken, C. Maturation-dependent HIV-1 Particle fusion requires a carboxyl-terminal region of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 9999–10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T. Roles of the interactions between Env and Gag proteins in the HIV-1 replication cycle. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 52, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Freed, E.O. Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and alpha-helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 3548–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Freed, E.O. The long cytoplasmic tail of gp41 is required in a cell type-dependent manner for HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein incorporation into virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kol, N.; Shi, Y.; Tsvitov, M.; Barlam, D.; Shneck, R.Z.; Kay, M.S.; Rousso, I. A stiffness switch in human immunodeficiency virus. Biophys. J. 2007, 92, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyma, D.J.; Jiang, J.; Shi, J.; Zhou, J.; Lineberger, J.E.; Miller, M.D.; Aiken, C. Coupling of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 fusion to virion maturation: A novel role of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 3429–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byland, R.; Vance, P.J.; Hoxie, J.A.; Marsh, M. A conserved dileucine motif mediates clathrin and AP-2-dependent endocytosis of the HIV-1 envelope protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 414–425. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, H.; Aguilar, R.C.; Fournier, M.C.; Hennecke, S.; Cosson, P.; Bonifacino, J.S. Interaction of endocytic signals from the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein complex with members of the adaptor medium chain family. Virology 1997, 238, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosson, P. Direct interaction between the envelope and matrix proteins of HIV-1. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 5783–5788. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavoni, I.; Trapp, S.; Santarcangelo, A.C.; Piacentini, V.; Pugliese, K.; Baur, A.; Federico, M. HIV-1 Nef enhances both membrane expression and virion incorporation of Env products. A model for the Nef-dependent increase of HIV-1 infectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 22996–23006. [Google Scholar]

- Sandrin, V.; Cosset, F.-L. Intracellular versus cell surface assembly of retroviral pseudotypes is determined by the cellular localization of the viral glycoprotein, its capacity to interact with Gag, and the expression of the Nef protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyma, D.J.; Kotov, A.; Aiken, C. Evidence for a stable interaction of gp41 with Pr55(Gag) in immature human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 9381–9387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, A.; Zhou, J.; Flicker, P.; Aiken, C. Association of Nef with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 8824–8830. [Google Scholar]

- Boge, M.; Wyss, S.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Thali, M. A membrane-proximal tyrosine-based signal mediates internalization of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein via interaction with the AP-2 clathrin adaptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 15773–15778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Mietzner, T.A.; Cloyd, M.W.; Robey, W.G.; Montelaro, R.C. Identification of a calmodulin-binding and inhibitory peptide domain in the HIV-1 transmembrane glycoprotein. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1993, 9, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tencza, S.B.; Miller, M.A.; Islam, K.; Mietzner, T.A.; Montelaro, R.C. Effect of amino acid substitutions on calmodulin binding and cytolytic properties of the LLP-1 peptide segment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 5199–5202. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Kao, S.; Whitehead, I.P.; Hart, M.J.; Liu, B.; Duus, K.; Burridge, K.; Der, C.J.; Su, L. Functional interaction between the cytoplasmic leucine-zipper domain of HIV-1 gp41 and p115-RhoGEF. Curr. Biol. 1999, 9, 1271–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Solski, P.A.; Hart, M.J.; Der, C.J.; Su, L. Modulation of HIV-1 replication by a novel RhoA effector activity. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 5369–5374. [Google Scholar]

- Blot, G.; Lopez-Vergès, S.; Treand, C.; Kubat, N.J.; Delcroix-Genête, D.; Emiliani, S.; Benarous, R.; Berlioz-Torrent, C. Luman, a new partner of HIV-1 TMgp41, interferes with Tat-mediated transcription of the HIV-1 LTR. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 364, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, V.; Haller, C.; Pfeiffer, T.; Fackler, O.T.; Bosch, V. Role of the C-terminal domain of the HIV-1 glycoprotein in cell-to-cell viral transmission between T lymphocytes. Retrovirology 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Murphy, L.C.; Murphy, L.J. The Prohibitins: Emerging roles in diverse functions. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2006, 10, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Ande, S.R.; Nyomba, B.L.G. The role of prohibitin in cell signaling. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 3937–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postler, T.S.; Desrosiers, R.C. The cytoplasmic domain of the HIV-1 glycoprotein gp41 induces NF-κB activation through TGF-β-activated kinase 1. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edinger, A.L.; Mankowski, J.L.; Doranz, B.J.; Margulies, B.J.; Lee, B.; Rucker, J.; Sharron, M.; Hoffman, T.L.; Berson, J.F.; Zink, M.C.; et al. CD4-independent, CCR5-dependent infection of brain capillary endothelial cells by a neurovirulent simian immunodeficiency virus strain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 14742–14747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.G.; Wyss, S.; Reeves, J.D.; Zolla-Pazner, S.; Hoxie, J.A.; Doms, R.W.; Baribaud, F. Truncation of the cytoplasmic domain induces exposure of conserved regions in the ectodomain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.; Sarkar, S.; Gupta, P.; Montelaro, R.C. Rational site-directed mutations of the LLP-1 and LLP-2 lentivirus lytic peptide domains in the intracytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 indicate common functions in cell-cell fusion but distinct roles in virion envelope incorporation. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 3634–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Steckbeck, J.D.; Kuhlmann, A.-S.; Montelaro, R.C. Structural and Functional Comparisons of Retroviral Envelope Protein C-Terminal Domains: Still Much to Learn. Viruses 2014, 6, 284-300. https://doi.org/10.3390/v6010284

Steckbeck JD, Kuhlmann A-S, Montelaro RC. Structural and Functional Comparisons of Retroviral Envelope Protein C-Terminal Domains: Still Much to Learn. Viruses. 2014; 6(1):284-300. https://doi.org/10.3390/v6010284

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteckbeck, Jonathan D., Anne-Sophie Kuhlmann, and Ronald C. Montelaro. 2014. "Structural and Functional Comparisons of Retroviral Envelope Protein C-Terminal Domains: Still Much to Learn" Viruses 6, no. 1: 284-300. https://doi.org/10.3390/v6010284

APA StyleSteckbeck, J. D., Kuhlmann, A.-S., & Montelaro, R. C. (2014). Structural and Functional Comparisons of Retroviral Envelope Protein C-Terminal Domains: Still Much to Learn. Viruses, 6(1), 284-300. https://doi.org/10.3390/v6010284