Increased Mortality Rates During the 2025 Chikungunya Epidemic in Réunion Island

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source and Preparation of Mortality and Population Data

2.1.1. Data Sources

2.1.2. Preparation of Mortality and Population Data

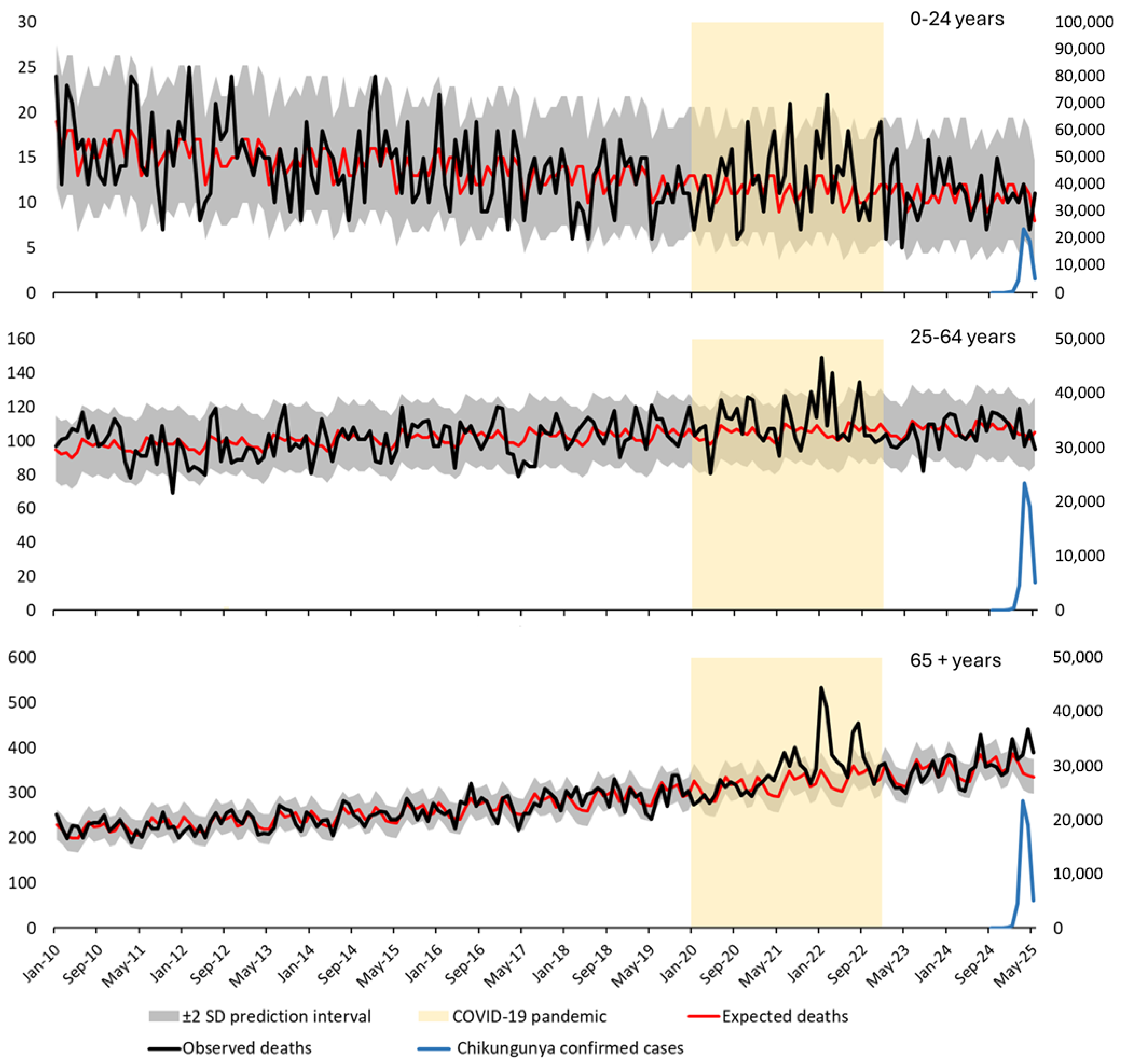

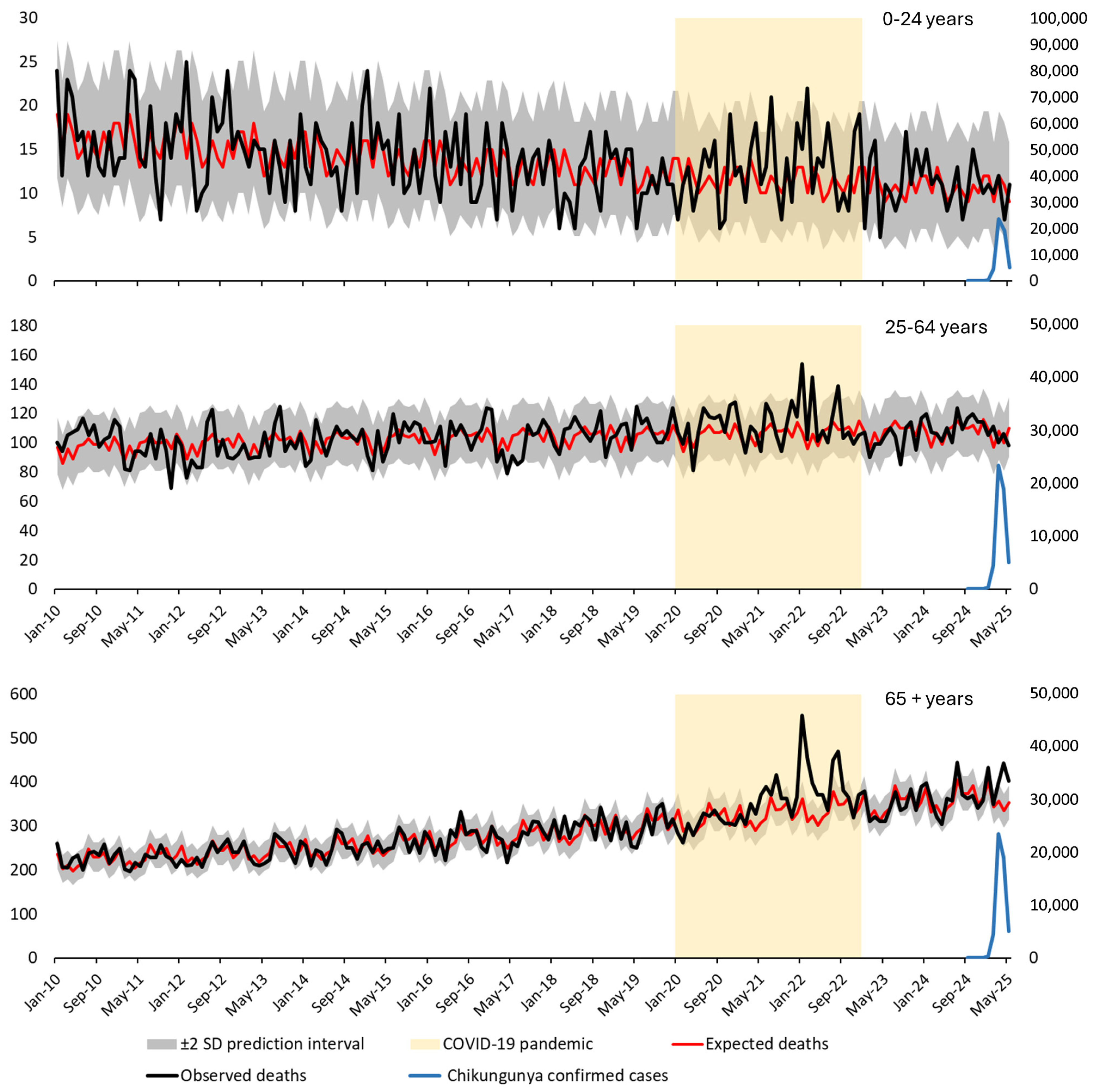

2.2. Age-Specific Expected Deaths Based on Post-Pandemic Baseline

2.3. Long-Term Mortality Modeling Using Poisson Regression (2010–2025)

2.3.1. Serfling-Type Regression, Harmonic Seasonality

2.3.2. Alternative Model Using Categorical Month Indicators

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Final Comments: Immediate Priorities for Action

6. Ethical Statements and Considerations

7. Transparency and Reproducibility

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, R.; Puri, V.; Fedorova, N.; Lin, D.; Hari, K.L.; Jain, R.; Rodas, J.D.; Das, S.R.; Shabman, R.S.; Weaver, S.C. Comprehensive Genome Scale Phylogenetic Study Provides New Insights on the Global Expansion of Chikungunya Virus. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 10600–10611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsetsarkin, K.A.; Chen, R.; Sherman, M.B.; Weaver, S.C. Chikungunya Virus: Evolution and Genetic Determinants of Emergence. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, S.T.S.; de Souza, W.M.; Cavalcante, J.W.; da Silva Candido, D.; Fumagalli, M.J.; Carrera, J.-P.; Simões Mello, L.M.; De Carvalho Araújo, F.M.; Cavalcante Ramalho, I.L.; de Almeida Barreto, F.K.; et al. Fatal Outcome of Chikungunya Virus Infection in Brazil. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e2436–e2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais Alves Barbosa Oliveira, R.; Kalline de Almeida Barreto, F.; Praça Pinto, G.; Timbó Queiroz, I.; Montenegro de Carvalho Araújo, F.; Wanderley Lopes, K.; Lúcia Sousa do Vale, R.; Rocha Queiroz Lemos, D.; Washington Cavalcante, J.; Machado Siqueira, A.; et al. Chikungunya Death Risk Factors in Brazil, in 2017: A Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0260939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.R.R.; de Góes Cavalcanti, L.P.; Gérardin, P. Chikungunya: Time to Change the Paradigm of a Non-Fatal Disease. InterAm. J. Med. Health 2020, 3, e202003001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, L.P.G.; Freitas, A.R.R.; Brasil, P.; da Cunha, R.V. Surveillance of Deaths Caused by Arboviruses in Brazil: From Dengue to Chikungunya. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2017, 112, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Góes Cavalcanti, L.P.; Gadelha Farias, L.A.B.; De Almeida Barreto, F.K.; Siqueira, A.M.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Freitas, A.R.R.; Weaver, S.C.; Kitron, U.; Brito, C.A.A. Chikungunya Case Classification after the Experience with Dengue Classification: How Much Time Will We Lose? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 102, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumence, E.; Piorkowski, G.; Traversier, N.; Amaral, R.; Vincent, M.; Mercier, A.; Ayhan, N.; Souply, L.; Pezzi, L.; Lier, C.; et al. Genomic Insights into the Re-Emergence of Chikungunya Virus on Réunion Island, France, 2024 to 2025. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30, 2500344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santé Publique France Canicule et Santé: Excès de Mortalité. Bulletin du 23 Juillet 2025. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/determinants-de-sante/climat/fortes-chaleurs-canicule/documents/bulletin-national/canicule-et-sante-exces-de-mortalite.-bulletin-du-23-juillet-2025 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Li, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Yang, Z.; Huang, X.; Guan, Q.; Li, Z.; Xie, J.; et al. An Outbreak of Chikungunya Fever in China—Foshan City, Guangdong Province, China, July 2025. CCDCW 2025, 7, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Seasonal Surveillance of Chikungunya Virus Disease in the EU/EEA. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/chikungunya-virus-disease/surveillance-and-updates/seasonal-surveillance (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Santé Publique France Surveillance sanitaire à La Réunion. Bulletin du 26 Juin 2025. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/regions/ocean-indien/documents/bulletin-regional/2025/surveillance-sanitaire-a-la-reunion.-bulletin-du-26-juin-2025 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques L’INSEE. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques?theme=0 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- M’nemosyme, N.; Frumence, E.; Souply, L.; Heaugwane, D.; Traversier, N.; Mercier, A.; Daoudi, J.; Casalegno, J.-S.; Valette, M.; Moiton, M.-P.; et al. Shifts in Respiratory Virus Epidemiology on Reunion Island From 2017 to 2023: Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic and Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2025, 19, e70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Trend Analysis Guidance for Surveillance Data; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Mortality Monitoring Activity Network EUROMOMO. Available online: https://euromomo.eu/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Liu, X.-X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, K.; Hu, M.; Qin, G.; Wang, X.-L. Seasonal Pattern of Influenza Activity in a Subtropical City, China, 2010–2015. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, W.J.; Viboud, C.; Simonsen, L.; Hirano, E.W.; Daufenbach, L.Z.; Miller, M.A. Seasonality of Influenza in Brazil: A Traveling Wave from the Amazon to the Subtropics. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 1434–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirve, S.; Newman, L.P.; Paget, J.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Fitzner, J.; Bhat, N.; Vandemaele, K.; Zhang, W. Influenza Seasonality in the Tropics and Subtropics—When to Vaccinate? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.E.; Chen, M. Influenza in Temperate and Tropical Asia: A Review of Epidemiology and Vaccinology. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Methods for Estimating the Excess Mortality Associated with the COVID-19 Pandemic; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas Freitas, A.R.; Lima Neto, A.S.; Rodrigues, R.; Alves de Oliveira, E.; Andrade, J.S.; Cavalcanti, L.P.G. Excess Mortality Associated with Chikungunya Epidemic in Southeast Brazil, 2023. Front. Trop. Dis. 2024, 5, 1466207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, C.P.; Andrews, N.J.; Beale, A.D.; Catchpole, M.A. A Statistical Algorithm for the Early Detection of Outbreaks of Infectious Disease. J. R. Stat. Society Ser. A (Stat. Soc.) 1996, 159, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statens Serum Institut. A European Algorithm for a Common Monitoring of Mortality Across Europe; Statens Serum Institut: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, J.K.; Chatterjee, S.N.; Chakravarty, S.K. Three-Year Study of Mosquito-Borne Haemorrhagic Fever in Calcutta. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1967, 61, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, H.; Bose, P.N.; Sehgal, P.N.; Mukherjee, R.N. Epidemiological Observations on the Outbreak of Acute Haemorrhagic Fever in Calcutta in 1963. In Report of the WHO Seminar on Mosquito-borne Haemorrhagic Fevers in South-East Asia and Western Pacific Regions, Bangkok, 19–26 October 1964; World Health Organization—Regional Office for South-East Asia and Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, S.P.; Gelfand, H.M.; Bose, P.N.; Sehgal, P.N.; Mukherjee, R.N. The Epidemic of Acute Haemorrhagic Fever, Calcutta, 1963: Epidemiological Inquiry. Indian J. Med. Res. 1964, 52, 633–650. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, A.R.R.; Donalisio, M.R.; Alarcón-Elbal, P.M. Excess Mortality and Causes Associated with Chikungunya, Puerto Rico, 2014–2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 2352–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.R.R.; Cavalcanti, L.; Zuben, A.P.V.; Donalisio, M.R. Excess Mortality Related to Chikungunya Epidemics In The Context Of Co-Circulation Of Other Arboviruses In Brazil. PLoS Curr. Outbreaks 2017, 9, 140491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavalankar, D.; Shastri, P.; Bandyopadhyay, T.; Parmar, J.; Ramani, K.V. Increased Mortality Rate Associated with Chikungunya Epidemic, Ahmedabad, India. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandale, B.V.; Sathe, P.S.; Arankalle, V.A.; Wadia, R.S.; Kulkarni, R.; Shah, S.V.; Shah, S.K.; Sheth, J.K.; Sudeep, A.B.; Tripathy, A.S.; et al. Systemic Involvements and Fatalities during Chikungunya Epidemic in India, 2006. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 46, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesoon, S.; Funkhouser, E.; Kotea, N.; Spielman, A.; Robich, R.M. Chikungunya Fever, Mauritius, 2006. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 337–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.R.R.; Gérardin, P.; Kassar, L.; Donalisio, M.R. Excess Deaths Associated with the 2014 Chikungunya Epidemic in Jamaica. Pathog. Glob. Health 2019, 113, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertillon, J. La Grippe à Paris et dans Quelques Autres Villes de France et de L’étranger en 1889–1890; Imprimerie Municipale: Paris, France, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Assaad, F.; Cockburn, W.C.; Sundaresan, T.K. Use of Excess Mortality from Respiratory Diseases in the Study of Influenza. Bull. World Health Organ. 1973, 49, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidance on Research Methods for Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pirard, P.; Vandentorren, S.; Pascal, M.; Laaidi, K.; Le Tertre, A.; Cassadou, S.; Ledrans, M. Summary of the Mortality Impact Assessment of the 2003 Heat Wave in France. Euro Surveill. Bull. Eur. Sur Les Mal. Transm.=Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2005, 10, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Josseran, L.; Paquet, C.; Zehgnoun, A.; Caillere, N.; Tertre, A.L.; Solet, J.-L.; Ledrans, M. Chikungunya Disease Outbreak, Reunion Island. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1994–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santé Publique France Bulletin Epidémiologique Hebdomadaire, 21 Octobre 2008, n°38-39-40 Qu’avons-nous Appris de L’épidémie de Chikungunya dans l’Océan Indien en 2005–2006? Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/import/bulletin-epidemiologique-hebdomadaire-21-octobre-2008-n-38-39-40-qu-avons-nous-appris-de-l-epidemie-de-chikungunya-dans-l-ocean-indien-en-2005-20 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Baghdadi, Y.; Gallay, A.; Caserio-Schönemann, C.; Fouillet, A. Evaluation of the French Reactive Mortality Surveillance System Supporting Decision Making. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 29, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorleans, F.; Hoen, B.; Najioullah, F.; Herrmann-Storck, E.; Maria Schepers, K.; Abel, S.; Lamaury, I.; Fagour, L.; Guyomard, S.; Troudard, R.; et al. Outbreak of Chikungunya in the French Caribbean Islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe: Findings from a Hospital-Based Surveillance System (2013-2015). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 1819–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas Freitas, A.R.; Alarcón-Elbal, P.M.; Donalisio, M.R. Excess Mortality in Guadeloupe and Martinique, Islands of the French West Indies, during the Chikungunya Epidemic of 2014. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 146, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frutuoso, L.C.V.; Freitas, A.R.R.; de Góes Cavalcanti, L.P.; Duarte, E.C. Estimated Mortality Rate and Leading Causes of Death among Individuals with Chikungunya in 2016 and 2017 in Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2020, 53, e20190580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerqueira-Silva, T.; Pescarini, J.M.; Cardim, L.L.; Leyrat, C.; Whitaker, H.; Antunes De Brito, C.A.; Brickley, E.B.; Barral-Netto, M.; Barreto, M.L.; Teixeira, M.G.; et al. Risk of Death Following Chikungunya Virus Disease in the 100 Million Brazilian Cohort, 2015–2018: A Matched Cohort Study and Self-Controlled Case Series. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira-Silva, T.; Cardim, L.L.; Paixão, E.; Rossi, M.; Santos, A.C.; Portela F De Souza, A.; Santos, G.; Barreto, M.L.; Brickley, E.B.; Pescarini, J.M. Hospitalisation, Mortality and Years of Life Lost among Chikungunya and Dengue Cases in Brazil: A Nationwide Cohort Study, 2015–2024. Lancet Reg. Health—Am. 2025, 49, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.M.D.; Melo, D.N.D.; Silva, M.M.D.; Souza, P.M.M.D.; Silva, F.K.D.S.; Coelho, T.M.S.; Lima, S.T.S.D.; Mota, A.G.D.M.; Monteiro, R.A.D.A.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; et al. Usefulness of Minimally Invasive Autopsy in the Diagnosis of Arboviruses to Increase the Sensitivity of the Epidemiological Surveillance System in Ceará, Brazil. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2024, 33, e2024008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, W.M.; Fumagalli, M.J.; de Lima, S.T.S.; Parise, P.L.; Carvalho, D.C.M.; Hernandez, C.; de Jesus, R.; Delafiori, J.; Candido, D.S.; Carregari, V.C.; et al. Pathophysiology of Chikungunya Virus Infection Associated with Fatal Outcomes. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 606–622.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economopoulou, A.; Dominguez, M.; Helynck, B.; Sissoko, D.; Wichmann, O.; Quenel, P.; Germonneau, P.; Quatresous, I. Atypical Chikungunya Virus Infections: Clinical Manifestations, Mortality and Risk Factors for Severe Disease during the 2005–2006 Outbreak on Réunion. Epidemiol. Infect. 2009, 137, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, T.M.; Keating, M.K.; Shieh, W.-J.; Bhatnagar, J.; Bollweg, B.C.; Levine, R.; Blau, D.M.; Torres, J.V.; Rivera, A.; Perez-Padilla, J.; et al. Clinical Characteristics, Histopathology, and Tissue Immunolocalization of Chikungunya Virus Antigen in Fatal Cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e345–e354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.R.R.; Pinheiro Chagas, A.A.; Siqueira, A.M.; Pamplona de Góes Cavalcanti, L. How Much of the Current Serious Arbovirus Epidemic in Brazil Is Dengue and How Much Is Chikungunya? Lancet Reg. Health—Am. 2024, 34, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Factsheet for Health Professionals About Chikungunya Virus Disease. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/chikungunya/facts/factsheet (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Chikungunya Fever Diagnosis and Treatment Plan (2025 Edition). Available online: https://cdcp.gd.gov.cn/ywdt/zdzt/yfjkkyr/yfjkkyrzs/content/post_4752702.html (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- World Health Organization—Regional Office for South-East Asia. Guidelines on Clinical Management of Chikungunya Fever; SEARO|WHO South-East Asia Region: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Menegale, F.; Manica, M.; Del Manso, M.; Bella, A.; Zardini, A.; Gobbi, A.; Mignuoli, A.D.; Mattei, G.; Vairo, F.; Vezzosi, L.; et al. Risk Assessment and Perspectives of Local Transmission of Chikungunya and Dengue in Italy, a European Forerunner. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidecker, B.; Libby, P.; Vassiliou, V.S.; Roubille, F.; Vardeny, O.; Hassager, C.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Mamas, M.A.; Cooper, L.T.; Schoenrath, F.; et al. Vaccination as a New Form of Cardiovascular Prevention: A European Society of Cardiology Clinical Consensus Statement. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 3518–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for Clinical Management of Arboviral Diseases: Dengue, Chikungunya, Zika and Yellow Fever; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; ISBN 978-92-4-011111-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas Freitas, A.R. Hughes Freitas, Luana Chikungunya Data and Analysis (GitHub). Available online: https://github.com/aribasfreitas/chikungunya (accessed on 21 July 2025).

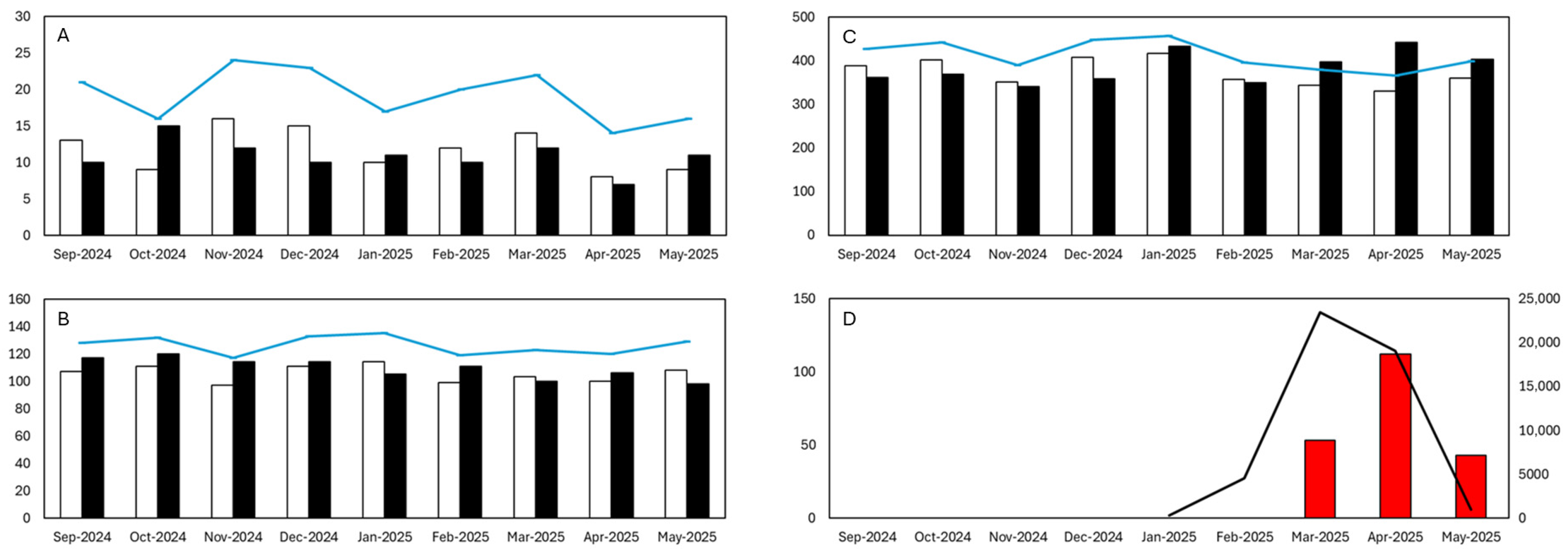

| Month | Age (years) | Observed Deaths | Expected Deaths | 95% CI | Excess Deaths | IRRm | 95% CI IRRm (Poisson) | 95% CI IRRm (Byar) | One–Tailed p–Value (Poisson) | Two–Tailed p–Value (Poisson) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-09 | <25 | 10 | 13 | [7–21] | — | 0.75 | [0.4–1.39] | [0.36–1.38] | 0.855 | 0.448 |

| 2024-10 | <25 | 15 | 9 | [4–16] | — | 1.6 | [0.96–2.65] | [0.89–2.64] | 0.055 | 0.110 |

| 2024-11 | <25 | 12 | 16 | [9–24] | — | 0.76 | [0.43–1.34] | [0.39–1.33] | 0.862 | 0.414 |

| 2024-12 | <25 | 10 | 15 | [8–23] | — | 0.65 | [0.35–1.22] | [0.31–1.2] | 0.939 | 0.210 |

| 2025-01 | <25 | 11 | 10 | [5–17] | — | 1.06 | [0.59–1.92] | [0.53–1.9] | 0.462 | 0.923 |

| 2025-02 | <25 | 10 | 12 | [6–20] | — | 0.81 | [0.44–1.51] | [0.39–1.49] | 0.785 | 0.628 |

| 2025-03 | <25 | 12 | 14 | [7–22] | — | 0.87 | [0.49–1.53] | [0.45–1.52] | 0.723 | 0.756 |

| 2025-04 | <25 | 7 | 8 | [3–14] | — | 0.89 | [0.42–1.86] | [0.36–1.83] | 0.673 | 0.937 |

| 2025-05 | <25 | 11 | 9 | [4–16] | — | 1.17 | [0.65–2.12] | [0.59–2.1] | 0.338 | 0.676 |

| 2024-09 | 25–64 | 117 | 107 | [87–128] | — | 1.09 | [0.91–1.31] | [0.91–1.31] | 0.176 | 0.352 |

| 2024-10 | 25–64 | 120 | 111 | [91–132] | — | 1.08 | [0.9–1.29] | [0.9–1.29] | 0.2054 | 0.411 |

| 2024-11 | 25–64 | 114 | 97 | [78–117] | — | 1.17 | [0.97–1.41] | [0.97–1.41] | 0.054 | 0.107 |

| 2024-12 | 25–64 | 114 | 111 | [91–133] | — | 1.02 | [0.85–1.23] | [0.84–1.23] | 0.414 | 0.829 |

| 2025-01 | 25–64 | 105 | 114 | [93–135] | — | 0.92 | [0.76–1.12] | [0.75–1.12] | 0.809 | 0.436 |

| 2025-02 | 25–64 | 111 | 99 | [80–119] | — | 1.12 | [0.93–1.35] | [0.92–1.35] | 0.121 | 0.242 |

| 2025-03 | 25–64 | 100 | 103 | [83–123] | — | 0.97 | [0.8–1.18] | [0.79–1.18] | 0.623 | 0.831 |

| 2025-04 | 25–64 | 106 | 100 | [81–120] | — | 1.06 | [0.87–1.28] | [0.87–1.28] | 0.298 | 0.596 |

| 2025-05 | 25–64 | 98 | 108 | [88–129] | — | 0.91 | [0.75–1.11] | [0.74–1.11] | 0.840 | 0.370 |

| 2024-09 | 65+ | 362 | 388 | [350–427] | — | 0.93 | [0.84–1.03] | [0.84–1.03] | 0.911 | 0.196 |

| 2024-10 | 65+ | 369 | 402 | [363–442] | — | 0.92 | [0.83–1.02] | [0.83–1.02] | 0.953 | 0.104 |

| 2024-11 | 65+ | 340 | 351 | [315–389] | — | 0.97 | [0.87–1.08] | [0.87–1.08] | 0.7343 | 0.567 |

| 2024-12 | 65+ | 358 | 408 | [369–448] | — | 0.88 | [0.79–0.97] | [0.79–0.97] | 0.994 | 0.013 |

| 2025-01 | 65+ | 433 | 416 | [377–457] | — | 1.04 | [0.95–1.14] | [0.94–1.14] | 0.211 | 0.422 |

| 2025-02 | 65+ | 349 | 357 | [321–395] | — | 0.98 | [0.88–1.09] | [0.88–1.09] | 0.674 | 0.692 |

| 2025-03 | 65+ | 397 | 344 | [308–380] | 53 | 1.16 | [1.05–1.27] | [1.04–1.27] | <0.0016 | <0.01 |

| 2025-04 | 65+ | 442 | 330 | [295–366] | 112 | 1.34 | [1.22–1.47] | [1.22–1.47] | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 2025-05 | 65+ | 403 | 360 | [323–398] | 43 | 1.12 | [1.01–1.23] | [1.01–1.23] | 0.05 | <0.05 |

| Total excess deaths | 208 |

| Serfling-Type Model | Nominal Model | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Age (years) | Observed Deaths | Expected | Expected − 2SD | Expected + 2SD | Excess Deaths | Z-Score | Expected | Expected − 2SD | Expected + 2SD | Excess Deaths | Z-Score |

| 2024-09 | <25 | 10 | 10 | 4.3 | 17.1 | — | 0.00 | 9 | 3.6 | 15.8 | — | 0.32 |

| 2024-10 | <25 | 15 | 11 | 5.3 | 18.8 | — | 1.15 | 11 | 5.1 | 18.2 | — | 1.15 |

| 2024-11 | <25 | 12 | 10 | 4.3 | 17.1 | — | 0.60 | 10 | 4.4 | 17.0 | — | 0.61 |

| 2024-12 | <25 | 10 | 12 | 6.1 | 20.1 | — | −0.60 | 12 | 5.9 | 19.4 | — | −0.61 |

| 2025-01 | <25 | 11 | 12 | 6.1 | 20.1 | — | −0.30 | 12 | 5.9 | 19.4 | — | −0.30 |

| 2025-02 | <25 | 10 | 9 | 4.0 | 15.9 | — | 0.00 | 9 | 3.6 | 15.8 | — | 0.32 |

| 2025-03 | <25 | 12 | 12 | 6.1 | 20.1 | — | 0.00 | 12 | 5.9 | 19.4 | — | 0.00 |

| 2025-04 | <25 | 7 | 11 | 5.1 | 18.2 | — | −1.30 | 11 | 5.1 | 18.2 | — | −1.31 |

| 2025-05 | <25 | 11 | 8 | 3.0 | 15.1 | — | 0.95 | 9 | 3.6 | 15.8 | — | 0.63 |

| 2024-09 | 25–64 | 117 | 110 | 90.3 | 130.9 | — | 0.68 | 110 | 90.4 | 130.9 | — | 0.68 |

| 2024-10 | 25–64 | 120 | 111 | 90.4 | 132.0 | — | 0.88 | 112 | 92.2 | 133.0 | — | 0.78 |

| 2024-11 | 25–64 | 114 | 107 | 87.5 | 127.8 | — | 0.69 | 106 | 86.6 | 126.7 | — | 0.79 |

| 2024-12 | 25–64 | 114 | 115 | 94.3 | 136.4 | — | −0.10 | 116 | 96.0 | 137.2 | — | −0.19 |

| 2025-01 | 25–64 | 105 | 111 | 90.4 | 132.0 | — | −0.50 | 109 | 89.4 | 129.8 | — | −0.40 |

| 2025-02 | 25–64 | 111 | 97 | 79.1 | 116.3 | — | 1.47 | 97 | 78.2 | 117.1 | — | 1.41 |

| 2025-03 | 25–64 | 100 | 107 | 87.5 | 128.7 | — | −0.71 | 108 | 88.5 | 128.8 | — | −0.80 |

| 2025-04 | 25–64 | 106 | 101 | 81.9 | 121.4 | — | 0.50 | 100 | 81.0 | 120.3 | — | 0.60 |

| 2025-05 | 25–64 | 98 | 109 | 88.5 | 129.8 | — | −1.02 | 110 | 90.4 | 130.9 | — | −1.21 |

| 2024-09 | 65+ | 362 | 371 | 332.2 | 411.2 | — | −0.46 | 374 | 335.3 | 414.1 | — | −0.61 |

| 2024-10 | 65+ | 369 | 393 | 352.3 | 434.5 | — | −1.12 | 391 | 351.7 | 431.7 | — | −1.11 |

| 2024-11 | 65+ | 340 | 347 | 309.1 | 386.3 | — | −0.36 | 348 | 310.2 | 387.2 | — | −0.42 |

| 2024-12 | 65+ | 358 | 365 | 325.4 | 405.6 | — | −0.31 | 365 | 326.6 | 404.8 | — | −0.36 |

| 2025-01 | 65+ | 433 | 400 | 359.3 | 442.0 | — | 1.63 | 400 | 360.4 | 441.0 | — | 1.62 |

| 2025-02 | 65+ | 349 | 343 | 307.4 | 380.9 | — | 0.30 | 343 | 305.4 | 382.0 | — | 0.31 |

| 2025-03 | 65+ | 397 | 355 | 316.4 | 396.0 | 42 | 2.04 | 357 | 318.9 | 396.5 | 40 | 2.02 |

| 2025-04 | 65+ | 442 | 338 | 300.5 | 377.0 | 104 | 5.19 | 334 | 296.8 | 372.7 | 108 | 5.42 |

| 2025-05 | 65+ | 403 | 347 | 308.5 | 387.4 | 56 | 2.76 | 353 | 315.0 | 392.4 | 50 | 2.53 |

| Excess deaths | 202 | 198 | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ribas Freitas, A.R.; Hughes Freitas, L.; Lima Neto, A.S.; Goes Cavalcanti, L.P.; Alarcón-Elbal, P.M. Increased Mortality Rates During the 2025 Chikungunya Epidemic in Réunion Island. Viruses 2026, 18, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020180

Ribas Freitas AR, Hughes Freitas L, Lima Neto AS, Goes Cavalcanti LP, Alarcón-Elbal PM. Increased Mortality Rates During the 2025 Chikungunya Epidemic in Réunion Island. Viruses. 2026; 18(2):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020180

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibas Freitas, André Ricardo, Luana Hughes Freitas, Antonio Silva Lima Neto, Luciano Pamplona Goes Cavalcanti, and Pedro María Alarcón-Elbal. 2026. "Increased Mortality Rates During the 2025 Chikungunya Epidemic in Réunion Island" Viruses 18, no. 2: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020180

APA StyleRibas Freitas, A. R., Hughes Freitas, L., Lima Neto, A. S., Goes Cavalcanti, L. P., & Alarcón-Elbal, P. M. (2026). Increased Mortality Rates During the 2025 Chikungunya Epidemic in Réunion Island. Viruses, 18(2), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020180