Replication and Transmission of Influenza A Virus in Farmed Mink

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Biosafety

2.2. Influenza Antibody Detection by Hemagglutination Inhibition (HI) Assay

2.3. Sialic Acid Receptor Detection in Mink Tissues

2.4. Viral Infection and Transmission Studies

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Seroprevalence of Antibodies Against Influenza Viruses in Farmed Mink

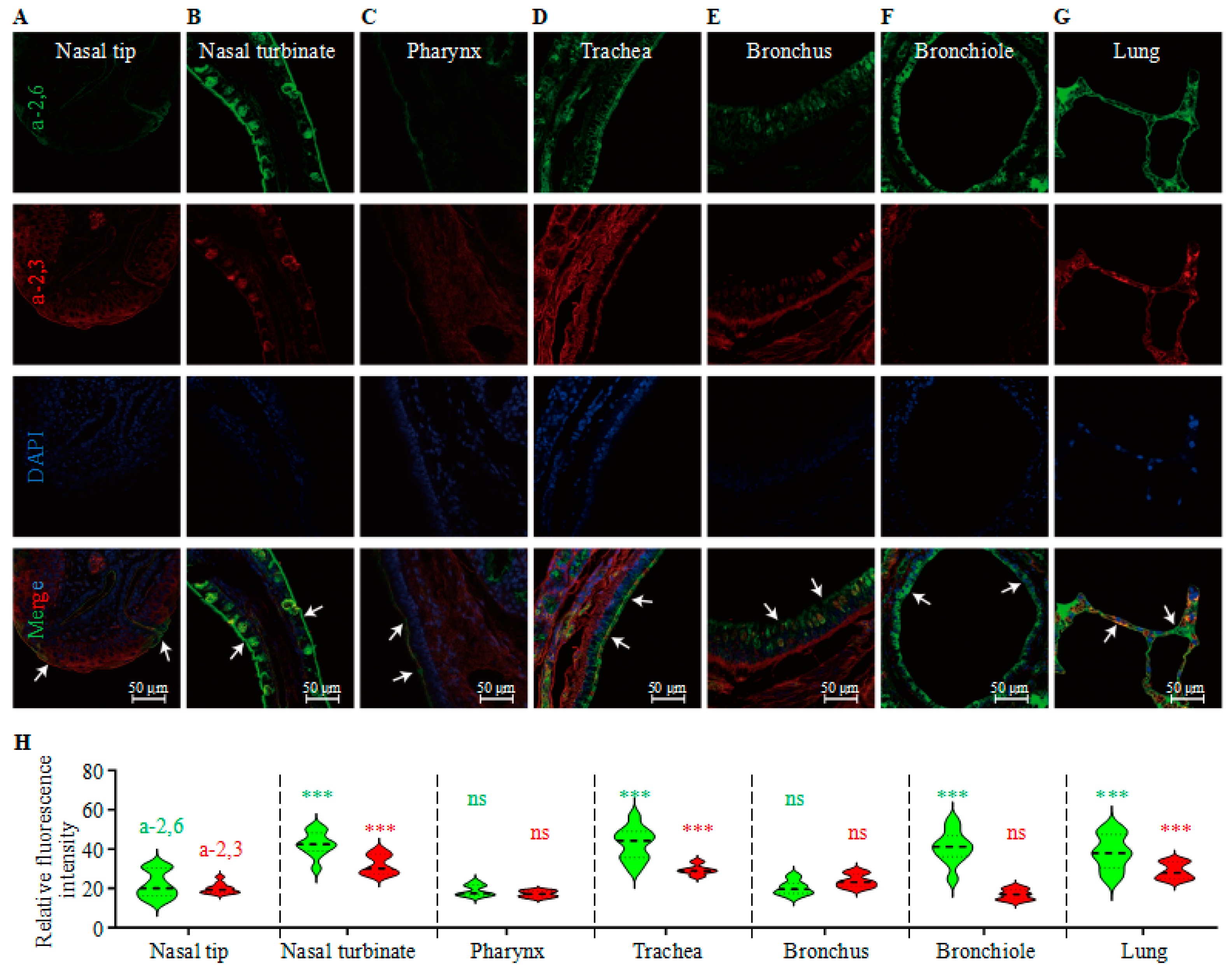

3.2. Analysis of the Receptor Distribution in the Respiratory System of Mink

3.3. Replication and Transmission of Circulating Avian Influenza Virus in Farmed Mink

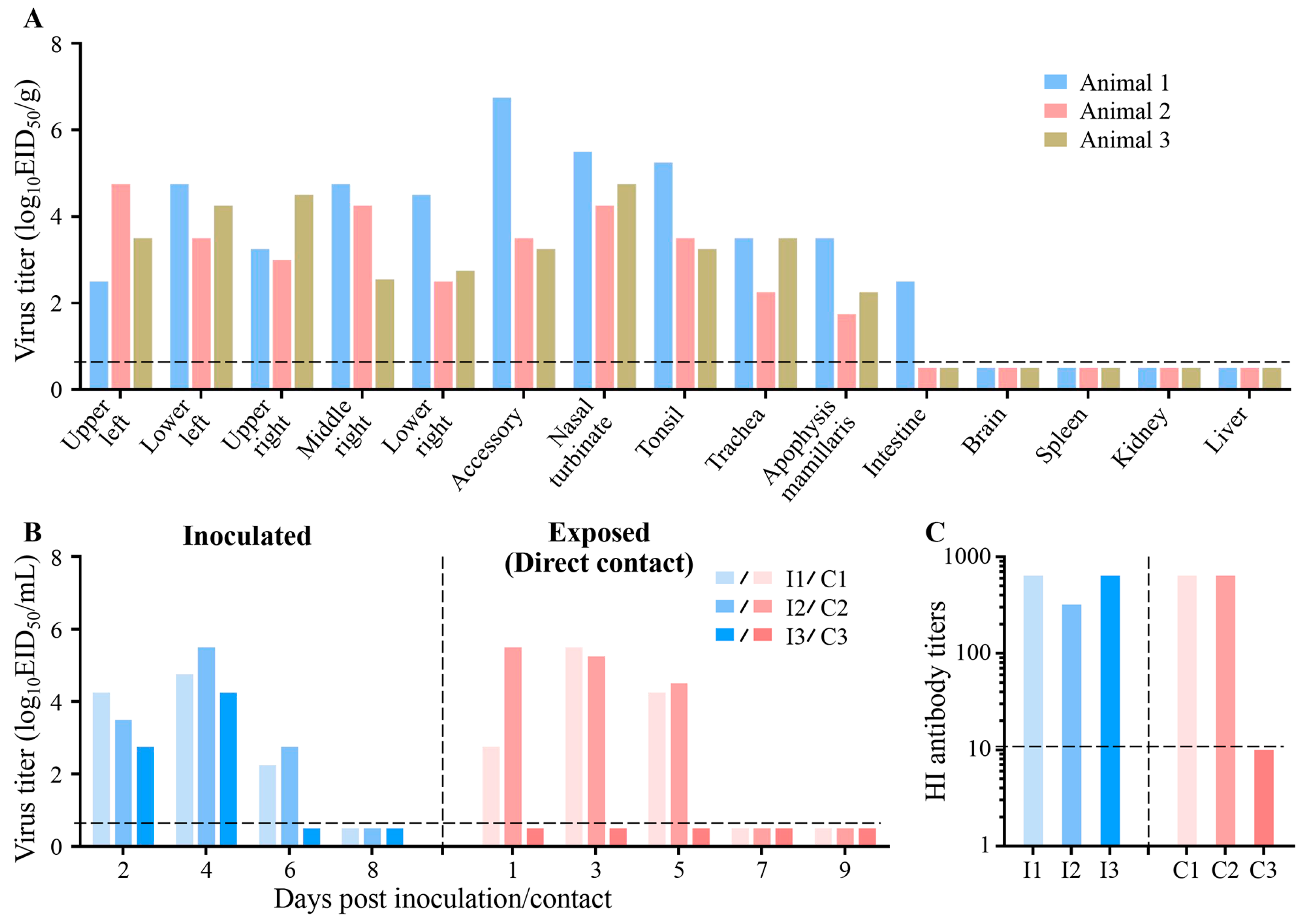

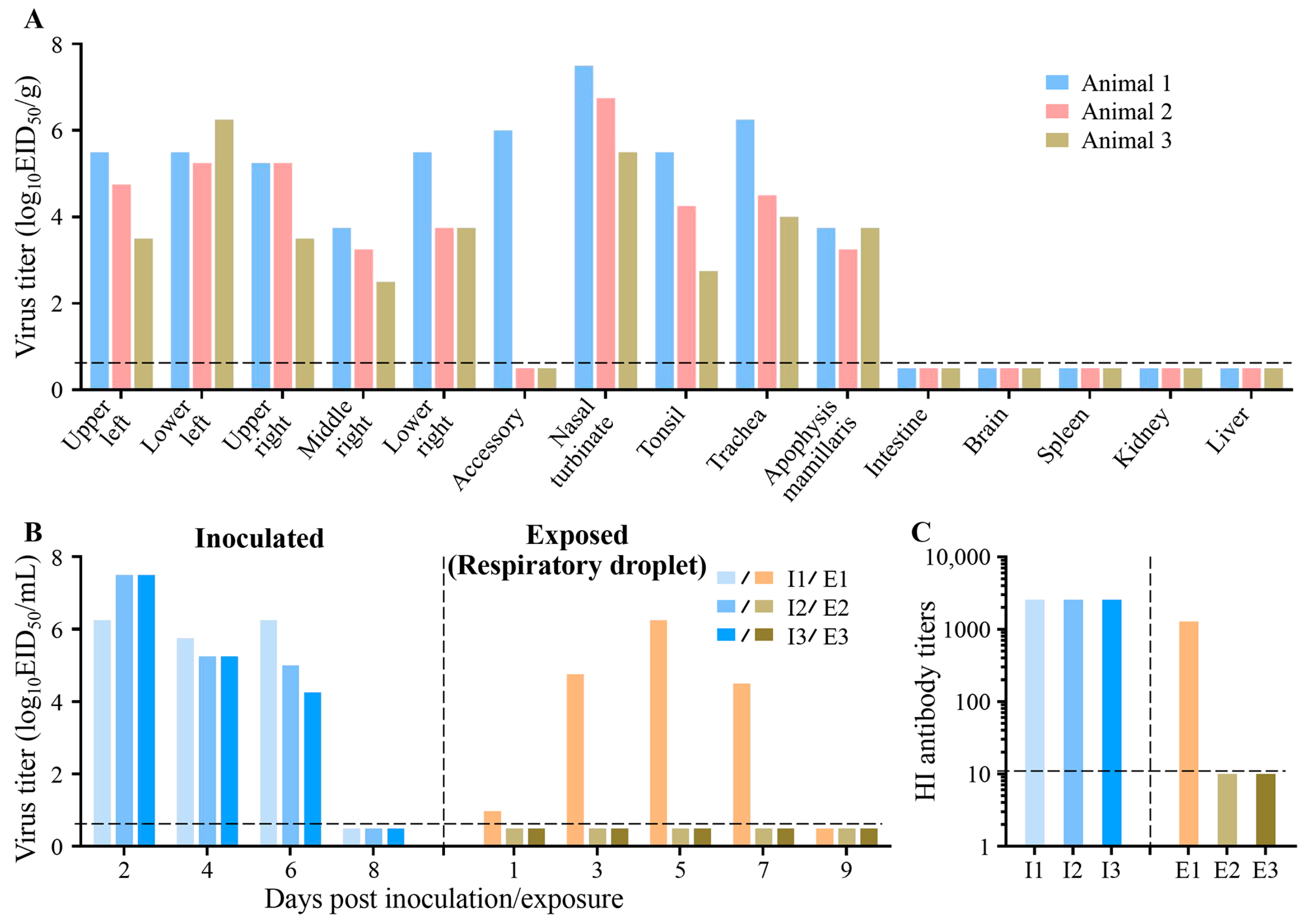

3.4. Replication and Transmission of Circulating Human Influenza Virus in Farmed Mink

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taubenberger, J.K.; Kash, J.C. Influenza virus evolution, host adaptation, and pandemic formation. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Zeng, X.; Cui, P.; Yan, C.; Chen, H. Alarming situation of emerging H5 and H7 avian influenza and effective control strategies. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2155072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Deng, G.; Cui, P.; Zeng, X.; Li, B.; Wang, D.; He, X.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Evolution of H7N9 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in the context of vaccination. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2343912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, F.; Liu, Q.; Du, J.; Liu, L.; Sun, H.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Mink is a highly susceptible host species to circulating human and avian influenza viruses. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shi, J.; Deng, G.; Guo, J.; Zeng, X.; He, X.; Kong, H.; Gu, C.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; et al. H7N9 influenza viruses are transmissible in ferrets by respiratory droplet. Science 2013, 341, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Trovao, N.S.; Wang, G.; Zhao, W.; He, P.; Zhou, H.; Mo, Y.; Wei, Z.; Ouyang, K.; Huang, W.; et al. Emergence and Evolution of Novel Reassortant Influenza A Viruses in Canines in Southern China. mBio 2018, 9, e00909-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Wang, G.; Mo, Y.; Yu, Q.; Xiao, X.; Yang, W.; Zhao, W.; Guo, X.; Chen, Q.; He, J.; et al. Novel triple-reassortant influenza viruses in pigs, Guangxi, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dos Anjos Borges, L.G.; Stadlbauer, D.; Ramos, I.; Bermudez Gonzalez, M.C.; He, J.; Ding, Y.; Wei, Z.; Ouyang, K.; Huang, W.; et al. Characterization of swine-origin H1N1 canine influenza viruses. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Qiao, C.; He, X.; Zhou, H.; Sun, Y.; Yin, H.; Meng, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Prevalence, genetics, and transmissibility in ferrets of Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaoka, Y.; Krauss, S.; Webster, R.G. Avian-to-human transmission of the PB1 gene of influenza A viruses in the 1957 and 1968 pandemics. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 4603–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.; Min Jou, W.; Huylebroeck, D.; Devos, R.; Fiers, W. Complete structure of A/duck/Ukraine/63 influenza hemagglutinin gene: Animal virus as progenitor of human H3 Hong Kong 1968 influenza hemagglutinin. Cell 1981, 25, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garten, R.J.; Davis, C.T.; Russell, C.A.; Shu, B.; Lindstrom, S.; Balish, A.; Sessions, W.M.; Xu, X.; Skepner, E.; Deyde, V.; et al. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science 2009, 325, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, Y.; He, X.; Kong, H.; Jiang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Xia, X.; Shu, Y.; Kawaoka, Y.; et al. Key molecular factors in hemagglutinin and PB2 contribute to efficient transmission of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus. J Virol 2012, 86, 9666–9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, L.; Hard af Segerstad, C. Two avian H10 influenza A virus strains with different pathogenicity for mink (Mustela vison). Arch. Virol. 1998, 143, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingeborn, B.; Englund, L.; Rott, R.; Juntti, N.; Rockborn, G. An avian influenza A virus killing a mammalian species--the mink. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 1985, 86, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englund, L.; Klingeborn, B.; Mejerland, T. Avian influenza A virus causing an outbreak of contagious interstitial pneumonia in mink. Acta Vet. Scand. 1986, 27, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, M.; Englund, L.; Abusugra, I.A.; Klingeborn, B.; Linne, T. Close relationship between mink influenza (H10N4) and concomitantly circulating avian influenza viruses. Arch. Virol. 1990, 113, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restori, K.H.; Septer, K.M.; Field, C.J.; Patel, D.R.; VanInsberghe, D.; Raghunathan, V.; Lowen, A.C.; Sutton, T.C. Risk assessment of a highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus from mink. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Chen, C.; Kai-yi, H.; Feng-xia, Z.; Yan-li, Z.; Zong-shuai, L.; Xing-xiao, Z.; Shi-jin, J.; Zhi-jing, X. Molecular characterization of H9N2 influenza virus isolated from mink and its pathogenesis in mink. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 176, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Cui, Y.; Yang, H.; Shan, H.; Zhang, C. Emergence of an Eurasian avian-like swine influenza A (H1N1) virus from mink in China. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 240, 108509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, L. Studies on influenza viruses H10N4 and H10N7 of avian origin in mink. Vet. Microbiol. 2000, 74, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Hou, G.; Peng, C.; Chen, J.; Shan, H. Characterization of H5N1 highly pathogenic mink influenza viruses in eastern China. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 201, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, C.A.; Spearman, G.; Hamel, A.; Godson, D.L.; Fortin, A.; Fontaine, G.; Tremblay, D. Characterization of a Canadian mink H3N2 influenza A virus isolate genetically related to triple reassortant swine influenza virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, M.J.; Kelly, E.J.; Mainenti, M.; Wilhelm, A.; Torchetti, M.K.; Killian, M.L.; Van Wettere, A.J. Pandemic lineage 2009 H1N1 influenza A virus infection in farmed mink in Utah. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2022, 34, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Kong, H.; Cui, P.; Deng, G.; Zeng, X.; Jiang, Y.; He, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhuang, Y.; et al. H5N1 virus invades the mammary glands of dairy cattle through ‘mouth-to-teat’ transmission. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Zhang, C.H.; Li, G.; Liu, G.; Shan, H.; Li, J. Two genetically similar H9N2 influenza viruses isolated from different species show similar virulence in minks but different virulence in mice. Acta Virol. 2020, 64, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo-Shun, Z.; Li, L.J.; Qian, Z.; Zhen, W.; Peng, Y.; Guo-Dong, Z.; Wen-Jian, S.; Xue-Fei, C.; Jiang, S.; Zhi-Jing, X. Co-infection of H9N2 influenza virus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa contributes to the development of hemorrhagic pneumonia in mink. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 240, 108542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Sun, L.; Xiong, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Yang, P.; Yu, H.; Yan, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, L.; et al. Semiaquatic mammals might be intermediate hosts to spread avian influenza viruses from avian to human. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong-Feng, Z.; Fei-Fei, D.; Jia-Yu, Y.; Feng-Xia, Z.; Chang-Qing, J.; Jian-Li, W.; Shou-Yu, G.; Kai, C.; Chuan-Yi, L.; Xue-Hua, W.; et al. Intraspecies and interspecies transmission of mink H9N2 influenza virus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xuan, Y.; Shan, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Li, G.; Qiao, J. Avian influenza virus H9N2 infections in farmed minks. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerstedt, J.; Valheim, M.; Germundsson, A.; Moldal, T.; Lie, K.I.; Falk, M.; Hungnes, O. Pneumonia caused by influenza A H1N1 2009 virus in farmed American mink (Neovison vison). Vet. Rec. 2012, 170, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, K.J.; Schwartz, K.; Sun, D.; Zhang, J.; Hildebrandt, H. Naturally occurring Influenza A virus subtype H1N2 infection in a Midwest United States mink (Mustela vison) ranch. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2012, 24, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, D.; Allard, V.; Doyon, J.F.; Bellehumeur, C.; Spearman, J.G.; Harel, J.; Gagnon, C.A. Emergence of a new swine H3N2 and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza A virus reassortant in two Canadian animal populations, mink and swine. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 4386–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nfon, C.; Berhane, Y.; Zhang, S.; Handel, K.; Labrecque, O.; Pasick, J. Molecular and antigenic characterization of triple-reassortant H3N2 swine influenza viruses isolated from pigs, turkey and quail in Canada. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2011, 58, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Cui, J. Cattle H5N1 outbreak in US driven by cow’s “cross-nursing” behaviour: Elucidating a novel transmission mechanism. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2547736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, T.P.; Barclay, W.S. Mink farming poses risks for future viral pandemics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2303408120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenollar, F.; Mediannikov, O.; Maurin, M.; Devaux, C.; Colson, P.; Levasseur, A.; Fournier, P.E.; Raoult, D. Mink, SARS-CoV-2, and the Human-Animal Interface. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 663815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T.B.; Qvesel, A.G.; Pedersen, A.G.; Olesen, A.S.; Fonager, J.; Rasmussen, M.; Sieber, R.N.; Stegger, M.; Calvo-Artavia, F.F.; Goedknegt, M.J.F.; et al. Emergence and spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants from farmed mink to humans and back during the epidemic in Denmark, June-November 2020. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oude Munnink, B.B.; Sikkema, R.S.; Nieuwenhuijse, D.F.; Molenaar, R.J.; Munger, E.; Molenkamp, R.; van der Spek, A.; Tolsma, P.; Rietveld, A.; Brouwer, M.; et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on mink farms between humans and mink and back to humans. Science 2021, 371, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Zhong, G.; Yuan, Q.; Wen, Z.; Wang, C.; He, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; et al. Replication, pathogenicity, and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in minks. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwaa291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Wen, Z.; Zhong, G.; Yang, H.; Wang, C.; Huang, B.; Liu, R.; He, X.; Shuai, L.; Sun, Z.; et al. Susceptibility of ferrets, cats, dogs, and other domesticated animals to SARS-coronavirus 2. Science 2020, 368, 1016–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Ai, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Tong, Q.; Liu, L.; Sun, H.; et al. COVID-19 restrictions limit the circulation of H3N2 canine influenza virus in China. One Health Advances 2024, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, Y.; Yanagawa, R.; Noda, H. Experimental infection of mink with influenza A viruses. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 1979, 62, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagyu, K.; Yanagawa, R.; Matsuura, Y.; Noda, H. Contact infection of mink with influenza A viruses of avian and mammalian origin. Arch. Virol. 1981, 68, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, K.; Yanagawa, R.; Kida, H. Contact infection of mink with 5 subtypes of avian influenza virus. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 1983, 77, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, K.; Yanagawa, R.; Kida, H.; Noda, H. Human influenza virus infection in mink: Serological evidence of infection in summer and autumn. Vet. Microbiol. 1983, 8, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagyu, K.; Yanagawa, R.; Matsuura, Y.; Fukushi, H.; Kida, H.; Noda, H. Serological survey of influenza A virus infection in mink. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi 1982, 44, 691–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cheng, K.; Wu, J. Serological evidence of the infection of H7 virus and the co-infection of H7 and H9 viruses in farmed fur-bearing animals in eastern China. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2020, 51, 2163–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, C.K.P.; Qin, K. Mink infection with influenza A viruses: An ignored intermediate host? One Health Adv. 2023, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Deng, G.; Shi, J.; Luo, W.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Li, C.; Sriwilaijaroen, N.; et al. H6 influenza viruses pose a potential threat to human health. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 3953–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maemura, T.; Guan, L.; Gu, C.; Eisfeld, A.; Biswas, A.; Halfmann, P.; Neumann, G.; Kawaoka, Y. Characterization of highly pathogenic clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 mink influenza viruses. EBioMedicine 2023, 97, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Yang, H.; Qu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zeng, X.; Li, C.; Kawaoka, Y.; et al. A Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza reassortant virus became pathogenic and highly transmissible due to mutations in its PA gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2203919119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Kahn, R.E.; Richt, J.A. The pig as a mixing vessel for influenza viruses: Human and veterinary implications. J. Mol. Genet. Med. 2008, 3, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinya, K.; Ebina, M.; Yamada, S.; Ono, M.; Kasai, N.; Kawaoka, Y. Avian flu: Influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature 2006, 440, 435–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riel, D.; Munster, V.J.; de Wit, E.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; Fouchier, R.A.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Kuiken, T. H5N1 Virus Attachment to Lower Respiratory Tract. Science 2006, 312, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razizadeh, M.H. Mink is an important possible route of introducing viral respiratory infections into the human population. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 1949–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowen, A.C.; Mubareka, S.; Tumpey, T.M.; Garcia-Sastre, A.; Palese, P. The guinea pig as a transmission model for human influenza viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 9988–9992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, H.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Deng, G.; Shi, J.; Tian, G.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; et al. H5N1 hybrid viruses bearing 2009/H1N1 virus genes transmit in guinea pigs by respiratory droplet. Science 2013, 340, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvier, N.M. Animal models for influenza virus transmission studies: A historical perspective. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015, 13, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, W.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Deng, G.; Shi, J.; Tian, G.; Zeng, X.; et al. Inactivated H9N2 vaccines developed with early strains do not protect against recent H9N2 viruses: Call for a change in H9N2 control policy. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 2144–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serum No. | SC/09 (H1N1) | DK/10 (H3N2) | DK/12 (H4N2) | DK/10 (H5N1) | CK/10 (H6N6) | DK/12 (H9N2) | DK/11 (H11N9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 2 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 3 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 4 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1280 | <10 |

| 5 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 6 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 7 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 8 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 9 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 80 | <10 |

| 10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 11 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| 12 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1280 | <10 |

| 13 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| 14 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 320 | <10 |

| 15 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1280 | <10 |

| 16 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 20 | <10 |

| 17 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1280 | <10 |

| 18 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1280 | <10 |

| 19 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 20 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 21 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 22 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 80 | <10 |

| 23 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 24 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 25 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 26 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 27 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1280 | <10 |

| 28 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 640 | <10 |

| 29 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 80 | <10 |

| 30 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 320 | <10 |

| 31 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| 32 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1280 | <10 |

| 33 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 40 | <10 |

| 34 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1280 | <10 |

| 35 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 160 | <10 |

| 36 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| 37 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 40 | <10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, G.; Gao, X.; Zhang, G.; Deng, G.; Shi, J. Replication and Transmission of Influenza A Virus in Farmed Mink. Viruses 2026, 18, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010009

Wang G, Gao X, Zhang G, Deng G, Shi J. Replication and Transmission of Influenza A Virus in Farmed Mink. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Guojun, Xiaoran Gao, Guoquan Zhang, Guohua Deng, and Jianzhong Shi. 2026. "Replication and Transmission of Influenza A Virus in Farmed Mink" Viruses 18, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010009

APA StyleWang, G., Gao, X., Zhang, G., Deng, G., & Shi, J. (2026). Replication and Transmission of Influenza A Virus in Farmed Mink. Viruses, 18(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010009