Developing Synthetic Full-Length SARS-CoV-2 cDNAs and Reporter Viruses for High-Throughput Antiviral Drug Screening

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

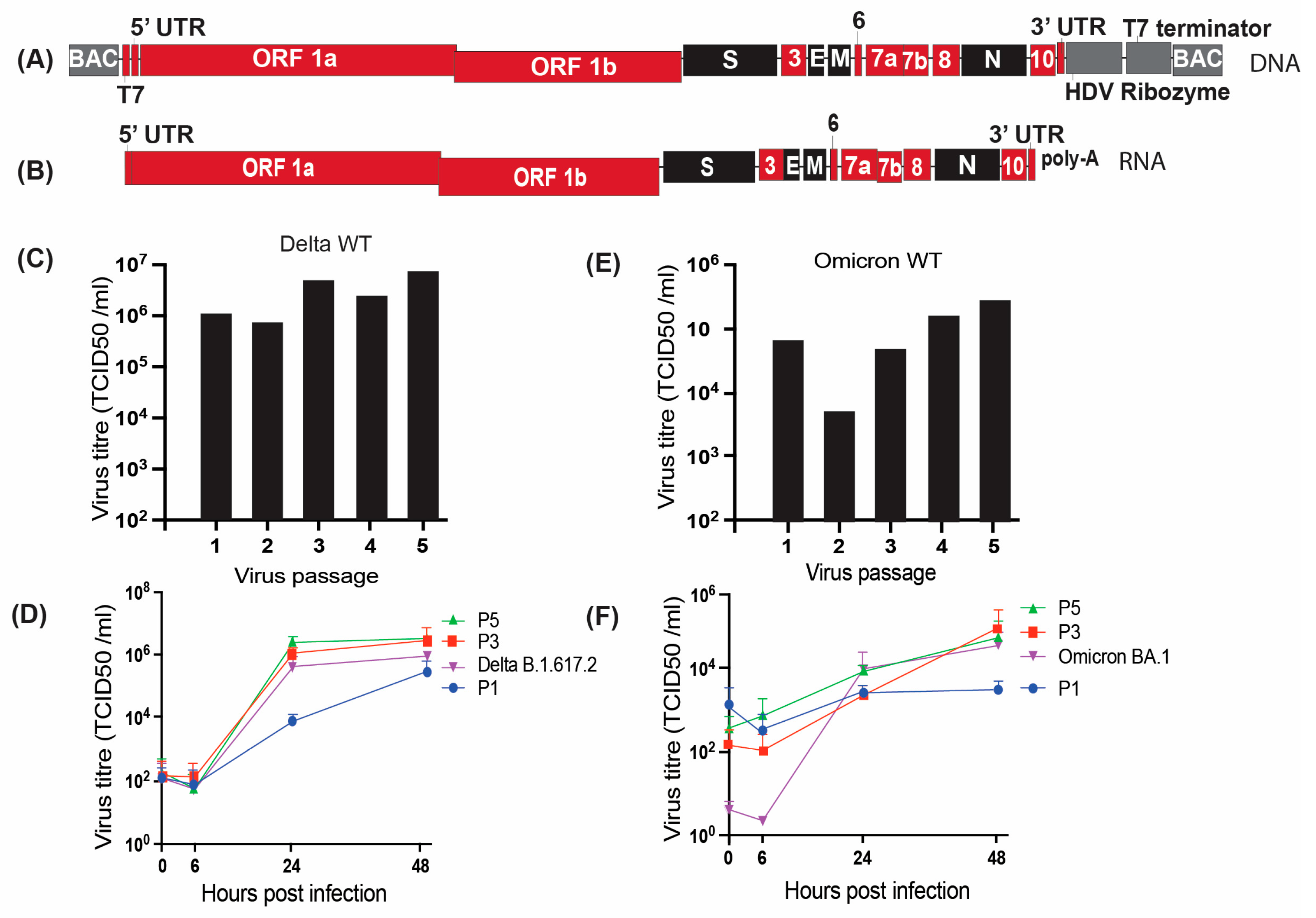

3.1. Generation of Wild-Type SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron Molecular Clones

3.2. Characterization of the Molecular Clone Derived Wild-Type Delta Virus

3.3. Characterization of the Wild-Type Omicron Virus Derived from a Molecular Clone

3.4. Generation of SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron Nano Luciferase Reporter Molecular Clones

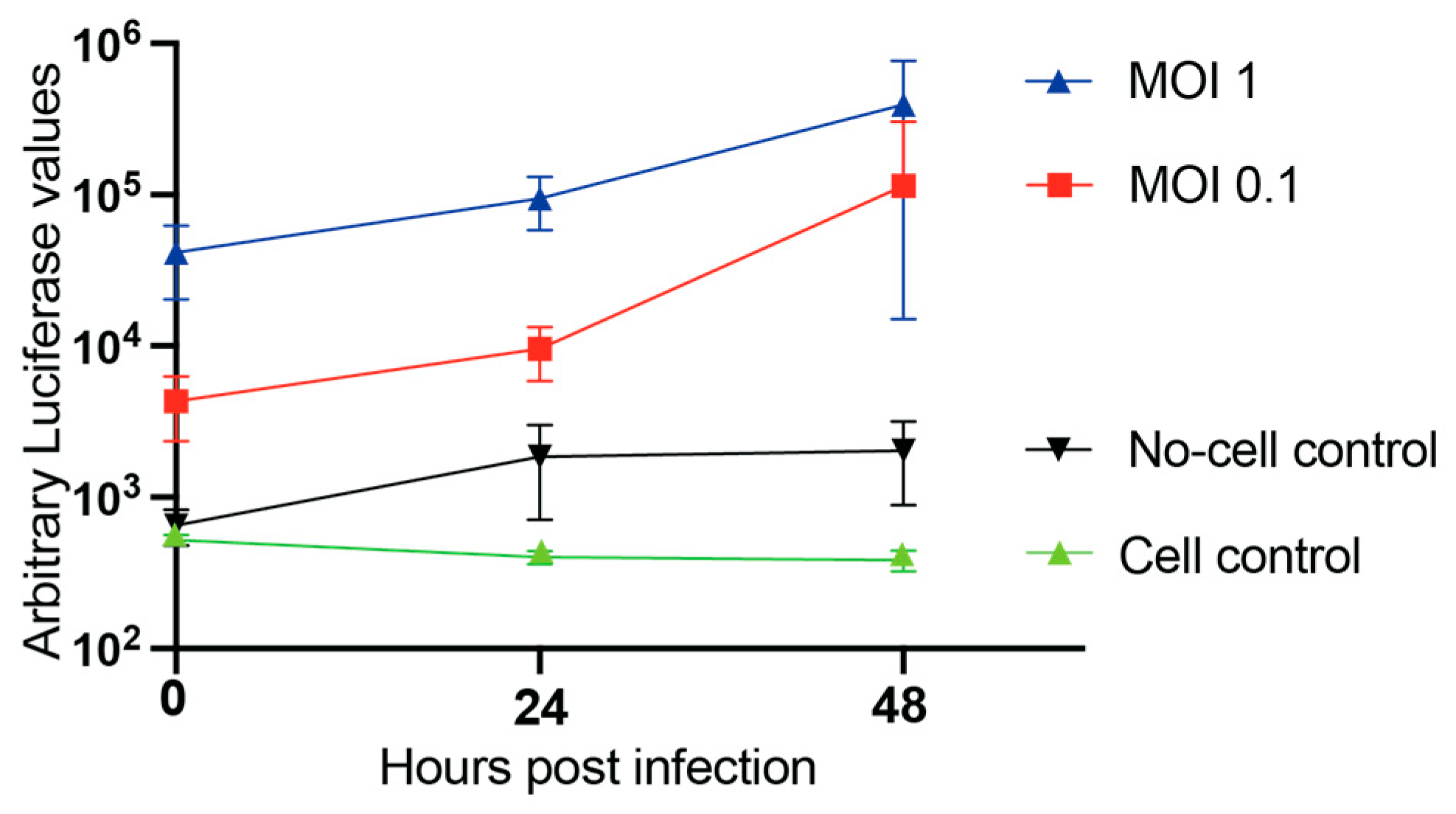

3.5. Nano-Luciferase SARS-CoV-2 Reporter Viruses as a Drug-Screening Tool

3.6. Comparative Growth Kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant in Primary Cells Using Nano-Luciferase Assays

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CC50 | 50% Cytotoxicity Concentration |

| TCID50 | 50% Tissue Culture Infectious Dose |

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BAC | Bacterial Artificial Chromosome |

| BSL3 | Biosafety Level 3 |

| BPE | Bovine Pituitary Extract |

| BEBM | Bronchial Epithelial Cell Growth Basal Medium |

| CIHR | Canadian Institutes of Health Research |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| CPE | Cytopathic Effect |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| MTS | Dimethylthiazol-Carboxymethoxyphenyl-Sulfophenyl-Tetrazolium |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s Phosphate-buffered Saline |

| EPI | Early Psychosis Intervention |

| E | Envelope |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GISAID | Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data |

| EC50 | Half Maximal Effective Concentration |

| IC50 | Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| HDV | Hepatitis Delta Virus |

| hEGF | Human Epidermal Growth Factor |

| IVT | In vitro transcription |

| Indels | Insertions/Deletions |

| M | Membrane |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

| μM | Micro molar |

| MOI | Multiplicity of Infection |

| Nluc | Nano Luciferase |

| NSERC | Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada |

| NSP | Non Structural Protein |

| NHBE | Normal Human Bronchial Epithelial |

| N | Nucleocapsid |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered Saline |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 |

| SI | Selectivity Index |

| SNPs | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| SET | Spreading Evidence-based Treatment |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| TRS | Transcription Regulatory Sequence |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

| VIDO | Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization |

| VOC | Variants of Concern |

| WT | Wild-Type |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Hartenian, E.; Nandakumar, D.; Lari, A.; Ly, M.; Tucker, J.M.; Glaunsinger, B.A. The molecular virology of coronaviruses. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 12910–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, A.; Droit, L.; Febles, B.; Fronick, C.; Cook, L.; Handley, S.A.; Parikh, B.A.; Wang, D. Tracking the prevalence and emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern using a regional genomic surveillance program. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0422523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfarcic, I.; Bui, T.; Daniels, E.C.; Troemel, E.R. Nanoluciferase-Based Method for Detecting Gene Expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2019, 213, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- England, C.G.; Ehlerding, E.B.; Cai, W. NanoLuc: A Small Luciferase Is Brightening Up the Field of Bioluminescence. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016, 27, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Peng, X.; Jin, Y.; Pan, J.A.; Guo, D. Reverse genetics systems for SARS-CoV-2. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 3017–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Zhang, X.; Vu, M.N.; Muruato, A.E.; Menachery, V.D.; Shi, P.Y. Engineering SARS-CoV-2 using a reverse genetic system. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 1761–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, C.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, X.; Zu, S.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H. Rapid Construction of Recombinant PDCoV Expressing an Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein for the Antiviral Screening Assay Based on Transformation-Associated Recombination Cloning in Yeast. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Nhu Thao, T.; Labroussaa, F.; Ebert, N.; V’Kovski, P.; Stalder, H.; Portmann, J.; Kelly, J.; Steiner, S.; Holwerda, M.; Kratzel, A.; et al. Rapid reconstruction of SARS-CoV-2 using a synthetic genomics platform. Nature 2020, 582, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, J.Q.; Rohamare, M.; Rajamanickam, K.; Bhanumathy, K.K.; Lew, J.; Kumar, A.; Falzarano, D.; Vizeacoumar, F.J.; Wilson, J.A. Generation of a SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics System and Novel Human Lung Cell Lines That Exhibit High Virus-Induced Cytopathology. Viruses 2023, 15, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Falzarano, D.; Gerdts, V.; Liu, Q. Construction of a noninfectious SARS-CoV-2 replicon for antiviral-drug testing and gene function studies. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0068721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durland, R.H.; Toukdarian, A.; Fang, F.; Helinski, D.R. Mutations in the trfA replication gene of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 result in elevated plasmid copy numbers. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 3859–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thio, C.L.; Hawkins, C. 148—Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis Delta Virus. In Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases (Eighth Edition); Bennett, J.E., Dolin, R., Blaser, M.J., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 1815–1839.e1817. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, R.; Zhao, P.; Xia, Q. 2A self-cleaving peptide-based multi-gene expression system in the silkworm Bombyx mori. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohamare, M.; Kumar, A.; Wilson, J.A. Large-Scale Culture and Plasmid Preparation Procedure for Low-Yield Bacmids Containing Full-Length SARS-CoV-2 cDNAs. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2813, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Muruato, A.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Narayanan, K.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.; Liu, J.; Schindewolf, C.; Bopp, N.E.; Aguilar, P.V.; et al. An Infectious cDNA Clone of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 841–848.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Lew, J.; Kroeker, A.; Baid, K.; Aftanas, P.; Nirmalarajah, K.; Maguire, F.; Kozak, R.; McDonald, R.; Lang, A.; et al. Immunogenicity of convalescent and vaccinated sera against clinical isolates of ancestral SARS-CoV-2, Beta, Delta, and Omicron variants. Med 2022, 3, 422–432.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hierholzer, J.; Killington, R. Suspension assay method. In Virology Methods Manual; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nirmalarajah, K.; Yim, W.; Aftanas, P.; Li, A.X.; Shigayeva, A.; Yip, L.; Zhong, Z.; McGeer, A.J.; Maguire, F.; Mubareka, S.; et al. Use of whole genome sequencing to identify low-frequency mutations in SARS-CoV-2 patients treated with remdesivir. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2023, 17, e13179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, J.A.; Kozak, R.A.; Aftanas, P.; Raphenya, A.R.; Smith, K.M.; Maguire, F.; Maan, H.; Alruwaili, M.; Banerjee, A.; Mbareche, H.; et al. A Comparison of Whole Genome Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 Using Amplicon-Based Sequencing, Random Hexamers, and Bait Capture. Viruses 2020, 12, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwa, J.D.; Jamal, A.J.; Mbareche, H.; Yip, L.; Aftanas, P.; Barati, S.; Bell, N.G.; Bryce, E.; Coomes, E.; Crowl, G.; et al. Surface and Air Contamination With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Hospitalized Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients in Toronto, Canada, March–May 2020. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.M.; Yount, B.; Baric, R.S. Heterologous gene expression from transmissible gastroenteritis virus replicon particles. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, D.K.; Gurijala, A.R.; Huang, L.; Hussain, A.A.; Lingan, A.L.; Pembridge, O.G.; Ratangee, B.A.; Sealy, T.T.; Vallone, K.T.; Clements, T.P. A guide to COVID-19 antiviral therapeutics: A summary and perspective of the antiviral weapons against SARS-CoV-2 infection. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 1632–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, K.T.; Wong, A.Y.; Kaewpreedee, P.; Sia, S.F.; Chen, D.; Hui, K.P.Y.; Chu, D.K.W.; Chan, M.C.W.; Cheung, P.P.; Huang, X.; et al. Remdesivir, lopinavir, emetine, and homoharringtonine inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cao, R.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Shi, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhong, W.; Xiao, G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Pang, Z.; Li, M.; Lou, F.; An, X.; Zhu, S.; Song, L.; Tong, Y.; Fan, H.; Fan, J. Molnupiravir and Its Antiviral Activity Against COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 855496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iketani, S.; Mohri, H.; Culbertson, B.; Hong, S.J.; Duan, Y.; Luck, M.I.; Annavajhala, M.K.; Guo, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Uhlemann, A.C.; et al. Multiple pathways for SARS-CoV-2 resistance to nirmatrelvir. Nature 2023, 613, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, R.; McGovern, B.L.; Rodriguez, M.L.; Leiva-Rebollo, R.; Diaz-Tapia, R.; Benjamin, J.; Rai, D.K.; Cardin, R.D.; Anderson, A.S.; PSP Study Group; et al. Nirmatrelvir and molnupiravir maintain potent in vitro and in vivo antiviral activity against circulating SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants. Antivir. Res. 2024, 230, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, A.; Zavala, D.; Rojas, J.; Posso, M.; Vaisberg, A. Efecto citotóxico selectivo in vitro de muricin H (acetogenina de Annona muricata) en cultivos celulares de cáncer de pulmón. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Pública 2006, 23, 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, W.; Chen, S.; Yuan, Z.; Yi, Z. A bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-vectored noninfectious replicon of SARS-CoV-2. Antivir. Res. 2021, 185, 104974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Deng, C.L.; Liu, J.; Li, J.Q.; Zhang, H.Q.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.N.; Li, X.D.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 replicon for high-throughput antiviral screening. J. Gen. Virol. 2021, 102, 001583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangeel, L.; Chiu, W.; De Jonghe, S.; Maes, P.; Slechten, B.; Raymenants, J.; André, E.; Leyssen, P.; Neyts, J.; Jochmans, D. Remdesivir, Molnupiravir and Nirmatrelvir remain active against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and other variants of concern. Antivir. Res. 2022, 198, 105252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Lavrijsen, M.; Lamers, M.M.; de Vries, A.C.; Rottier, R.J.; Bruno, M.J.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Haagmans, B.L.; Pan, Q. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is highly sensitive to molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, and the combination. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Virus, Mutation and Passage | Nucleotide Position | Nucleotide Change | Amino Acid Change | Viral Gene | p2 | p3 | p4 | p5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delta WT | 21,802 | T-A | Asn-Lys | Spike | x | |||

| Delta Nluc | 284 | A-G | Ser-Gly | NSP3 | x | x | x | |

| 3643 | A-C | No change | NSP3 | x | x | x | ||

| 26,273 | C-T | ser-Leu | E | x | x | x | ||

| Omicron WT | 348 | A-G | Gln-Arg | NSP1 | x | x | ||

| 10,949 | T-A | Phe-Ile | NSP5 | x | x | |||

| 24,752 | G-A | Val-Met | S | x | x | |||

| 26,258 | C-T | Ser-Leu | E | x | x | |||

| Omicron Nluc | 7345 | A-C | No change | NSP4 | x | x | x | x |

| 13,579 | A-G | Thr-Ala | NSP12 | x | x | x | x | |

| 17,457 | A-G | No change | NSP13 | x | x | x | x | |

| 17,466 | A-G | No change | NSP13 | x | x | x | x | |

| 17,483 | A-G | Lys-Arg | NSP13 | x | x | x | x | |

| 26,330 | C-G | Thr-Arg | E | x | x | x | x | |

| 26,844 | A-C | Met-Leu | M | x | x | x | x | |

| 23,684 | A-G | Asn-Asp | S | x | x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rohamare, M.; Kaushik, N.; Khan, J.Q.; Balouchi, M.; Lopez-Orozco, J.; Kozak, R.; Hobman, T.C.; Falzarano, D.; Kumar, A.; Wilson, J.A. Developing Synthetic Full-Length SARS-CoV-2 cDNAs and Reporter Viruses for High-Throughput Antiviral Drug Screening. Viruses 2026, 18, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010044

Rohamare M, Kaushik N, Khan JQ, Balouchi M, Lopez-Orozco J, Kozak R, Hobman TC, Falzarano D, Kumar A, Wilson JA. Developing Synthetic Full-Length SARS-CoV-2 cDNAs and Reporter Viruses for High-Throughput Antiviral Drug Screening. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleRohamare, Megha, Nidhi Kaushik, Juveriya Qamar Khan, Mahrokh Balouchi, Joaquin Lopez-Orozco, Robert Kozak, Tom C. Hobman, Darryl Falzarano, Anil Kumar, and Joyce A. Wilson. 2026. "Developing Synthetic Full-Length SARS-CoV-2 cDNAs and Reporter Viruses for High-Throughput Antiviral Drug Screening" Viruses 18, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010044

APA StyleRohamare, M., Kaushik, N., Khan, J. Q., Balouchi, M., Lopez-Orozco, J., Kozak, R., Hobman, T. C., Falzarano, D., Kumar, A., & Wilson, J. A. (2026). Developing Synthetic Full-Length SARS-CoV-2 cDNAs and Reporter Viruses for High-Throughput Antiviral Drug Screening. Viruses, 18(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010044