Redesigning Isolation Practices: Evaluation of a Comprehensive Protocol for Respiratory Virus Control Including Cycle Threshold (Ct) Value Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

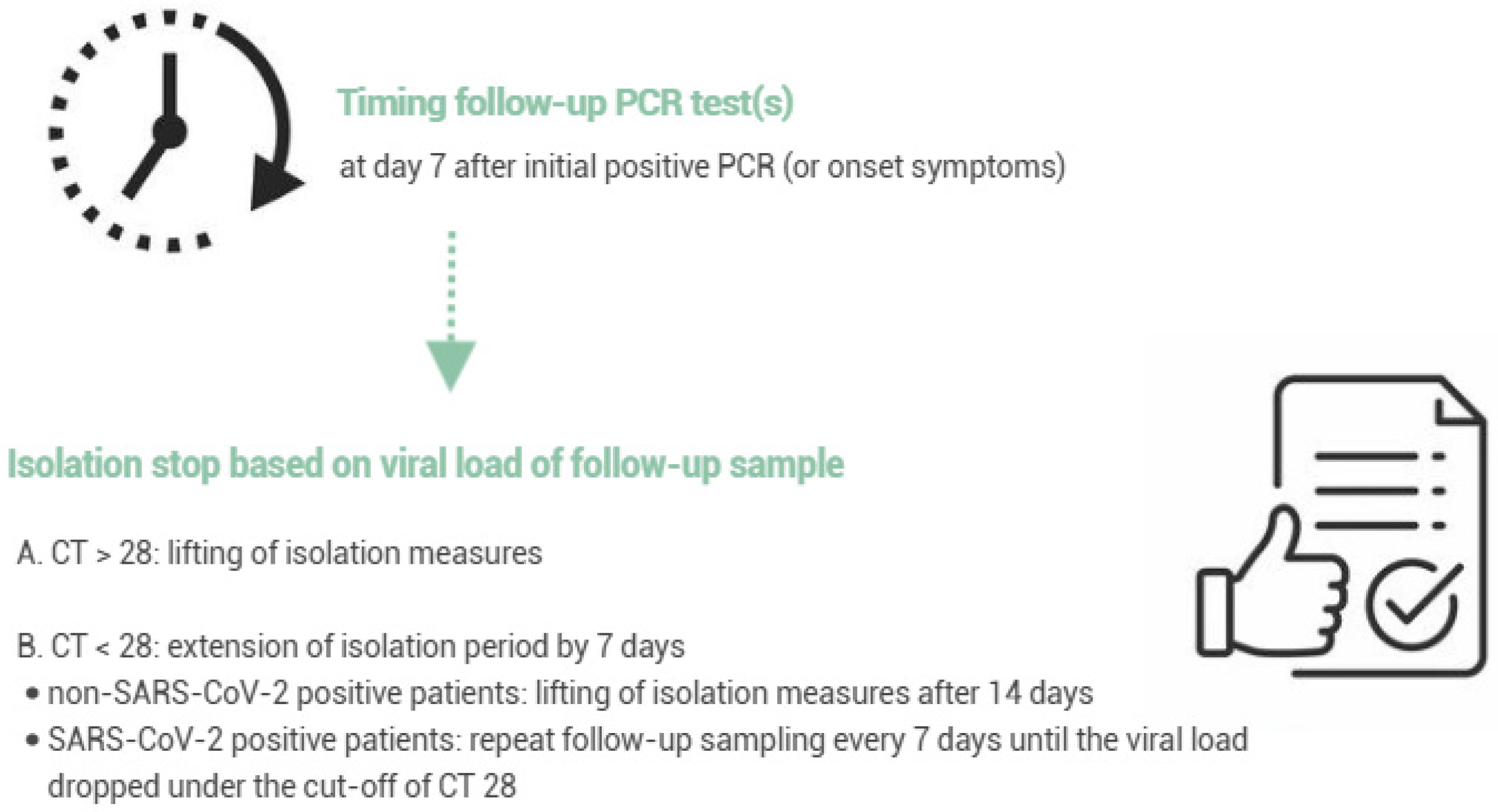

2.1. Evaluation of the Revised Respiratory Isolation Measures

2.2. Clinical Specimens and Patients

2.3. Molecular Assays

2.4. Associations Between Treatment and Viral Loads

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of the Revised Respiratory Isolation Measures

3.2. Patient Characteristics

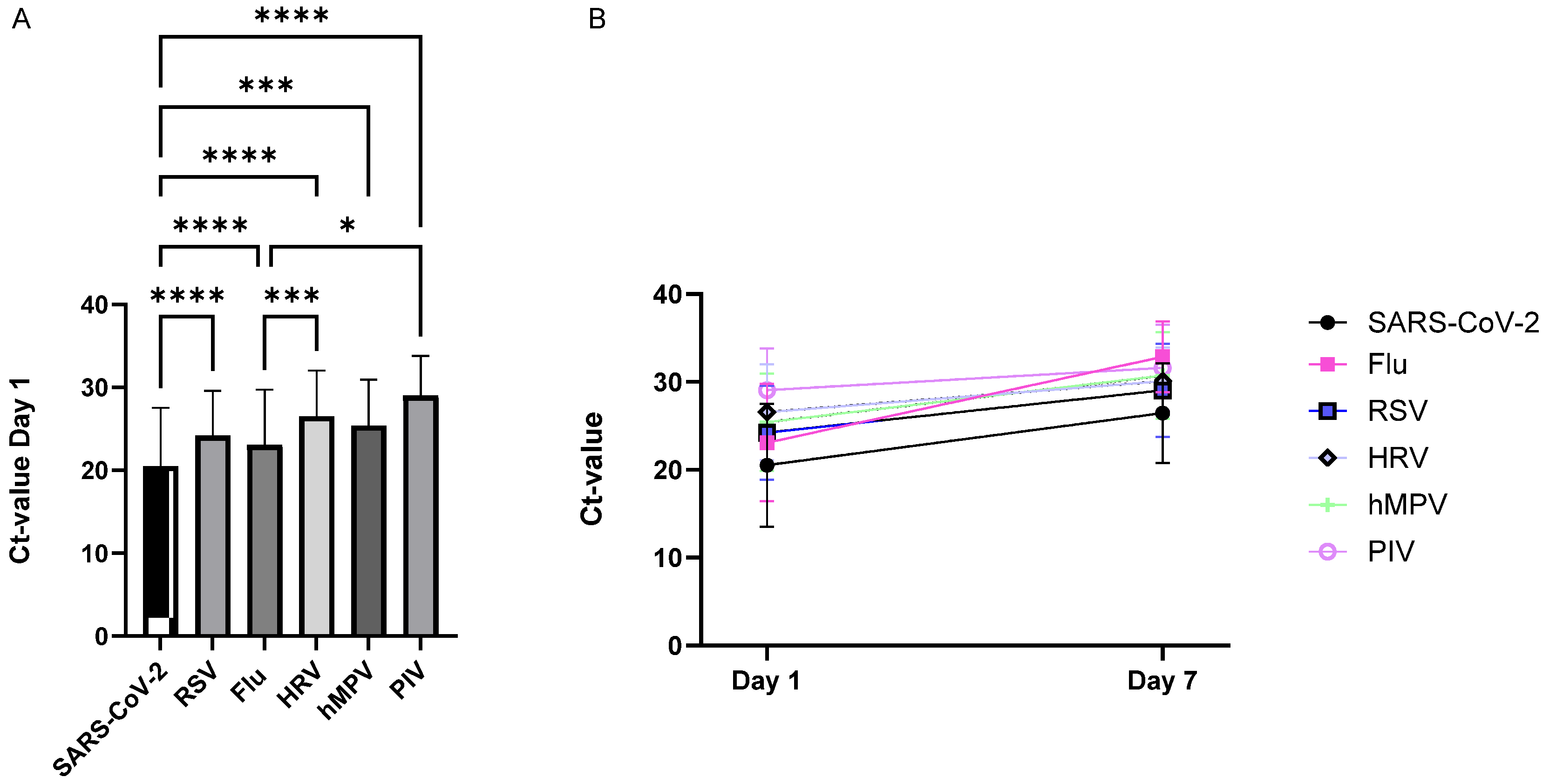

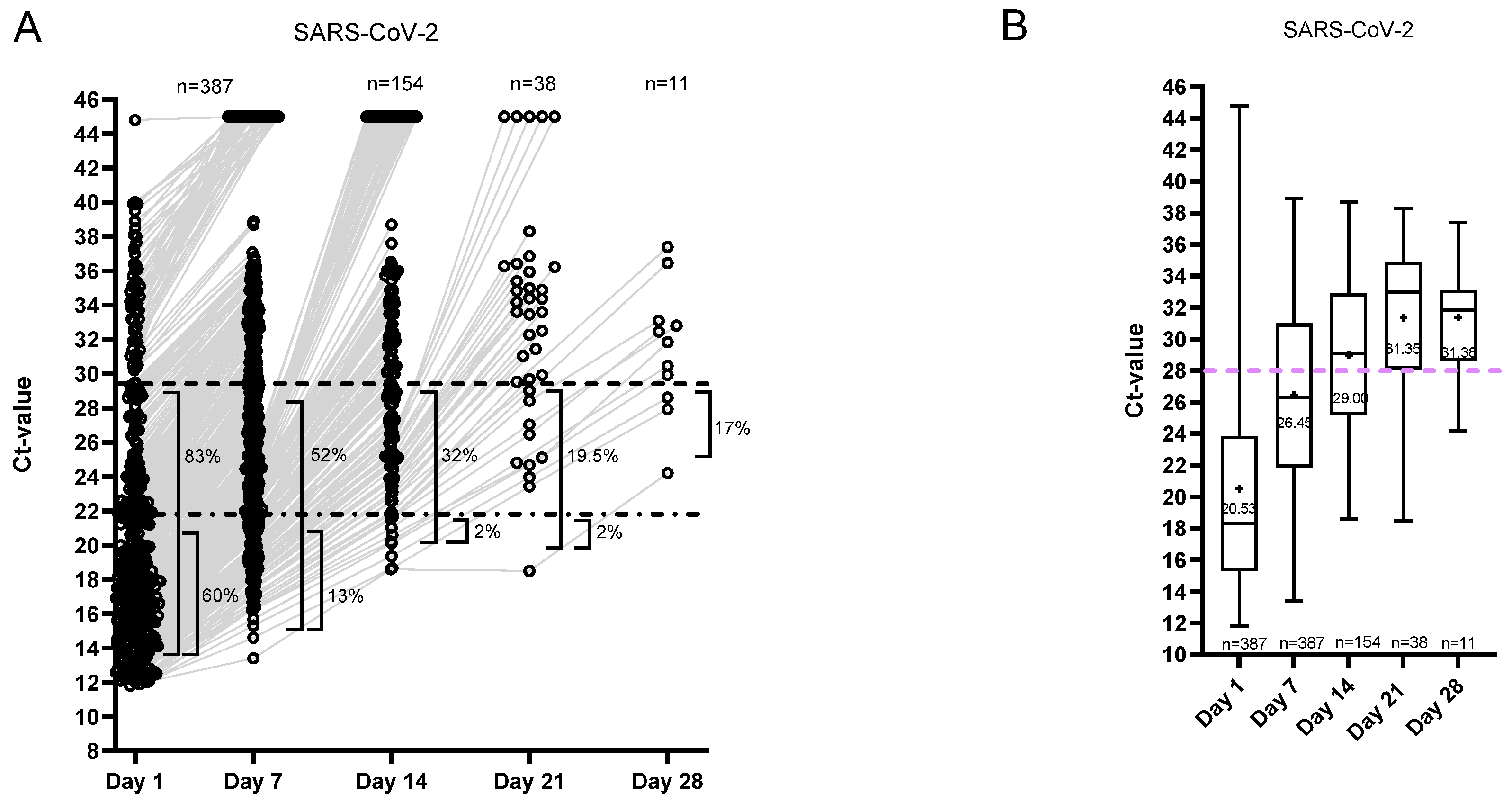

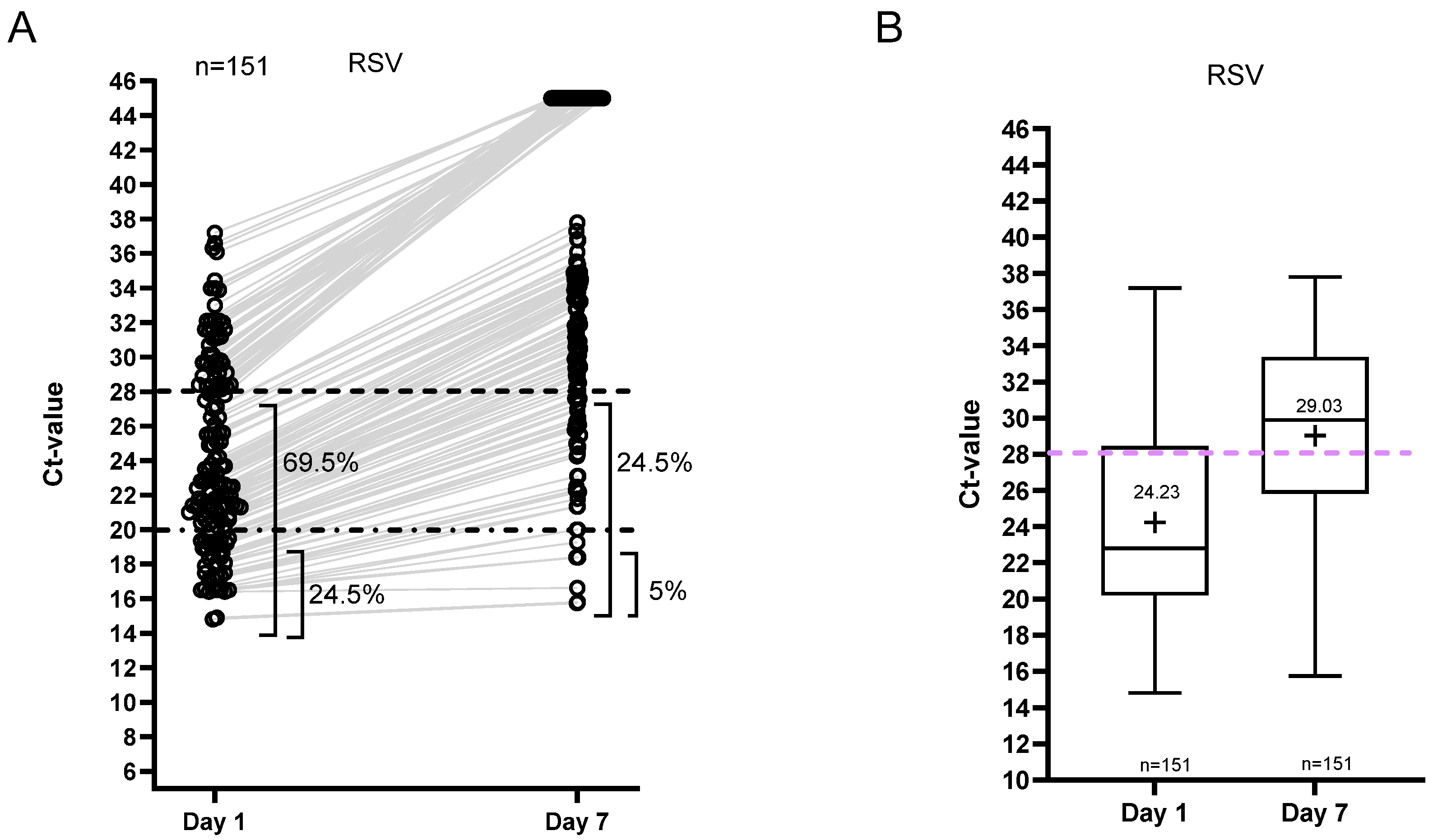

3.3. Ct Value Dynamics

3.4. Isolation and Hospitalization Duration

3.5. Associations Between Oseltamivir Treatment and Viral Loads for Influenza Patients

4. Discussion

Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ct | Cycle threshold |

| D | Days |

| DEP | Department |

| DIV | Diverse departments |

| FU | Follow up |

| GER | Geriatrics |

| ICA | Intensive care unit |

| INT | Internal medicine |

| N | Number |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

References

- Wang, C.C.; Prather, K.A.; Sznitman, J.; Jimenez, J.L.; Lakdawala, S.S.; Tufekci, Z.; Marr, L.C. Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses. Science 2021, 373, eabd9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrie, M.; Loh, M.; Cherrie, J. The relative effectiveness of personal protective equipment and environmental controls in protecting healthcare workers from COVID-19. Ann. Work. Expo. Health 2025, 69, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhegazy, M.; Talaat, K.; Anderoglu, O.; Poroseva, S.V.; Talaat, K. Numerical investigation of aerosol transport in a classroom with relevance to COVID-19. Phys. Fluids 2020, 32, 103311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, X.; Yao, F.; Chen, Y. Numerical study of virus transmission through droplets from sneezing in a cafeteria. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33, 023311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumuru, V.; Kusuluri, R.; Mirikar, D. Role of face masks and ventilation rates in mitigating respiratory disease transmission in ICU. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singanayagam, A.; Patel, M.; Charlett, A.; Bernal, J.L.; Saliba, V.; Ellis, J.; Ladhani, S.; Zambon, M.; Gopal, R. Duration of infectiousness and correlation with RT-PCR cycle threshold values in cases of COVID-19, England, January to May 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2001483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, C.; Kleynhans, J.; Moyes, J.; Treurnicht, F.K.; Hellferscee, O.; Mathunjwa, A.; von Gottberg, A.; Wolter, N.; Kahn, K.; Lebina, L.; et al. Asymptomatic transmission and high community burden of seasonal influenza in an urban and a rural community in South Africa, 2017–2018(PHIRST): A population cohort study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e863–e874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, D.W.; Futschik, M.; Tunkel, S.; Wei, J.; Cole-Hamilton, J.; Saquib, R.; Germanacos, N.; Dodgson, A.R.; Klapper, P.E.; Sudhanva, M.; et al. Performance of antigen lateral flow devices in the UK during the alpha, delta, and omicron waves of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: A diagnostic and observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marot, S.; Calvez, V.; Louet, M.; Marcelin, A.; Burrel, S. Interpretation of SARS-CoV-2 replication according to RT-PCR crossing threshold value. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1056–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassetto, M.; Garcia-Knight, M.; Anglin, K.; Lu, S.; Zhang, A.; Romero, M.; Pineda-Ramirez, J.; Sanchez, R.D.; Donohue, K.C.; Pfister, K.; et al. Detection of Higher Cycle Threshold Values in Culturable SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 Sublineage Compared with Pre-Omicron Variant Specimens—San Francisco Bay Area, California, July 2021–March 2022. Mmwr-Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fall, A.; Eldesouki, R.; Sachithanandham, J.; Morris, C.P.; Norton, J.M.; Gaston, D.C.; Forman, M.; Abdullah, O.; Gallagher, N.; Li, M.; et al. The displacement of the SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta with Omicron: An investigation of hospital admissions and upper respiratory viral loads. EBioMedicine 2022, 79, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.; Eldesouki, R.; Sachithanandham, J.; Fall, A.; Norton, J.M.; Abdullah, O.; Gallagher, N.; Li, M.; Pekosz, A.; Klein, E.Y.; et al. Omicron Subvariants: Clinical, Laboratory, and Cell Culture Characterization. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 76, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooding, D.; Buist, K.; Romero-Ramirez, A.; Savage, H.; Watkins, R.; Bengey, D.; Greenland-Bews, C.; Thompson, C.R.; Kontogianni, N.; Body, R.; et al. Optimization of SARS-CoV-2 culture from clinical samples for clinical trial applications. Msphere 2024, 9, e0030424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenzeller, S.; Zaffini, R.; Pecora, N.; Kanjilal, S.; Rhee, C.; Klompas, M. Cycle threshold dynamics of non–severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) respiratory viruses. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2024, 45, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, X. Comparative Review of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and Influenza A Respiratory Viruses. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 552909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asseri, A.A. Respiratory Syncytial Virus: A Narrative Review of Updates and Recent Advances in Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Management and Prevention. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, K.; Faramarzi, S.; Yaribash, S.; Valizadeh, Z.; Rajabi, E.; Ghavam, M.; Samiee, R.; Karim, B.; Salehi, M.; Seifi, A. Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) in 2025: Emerging trends and insights from community and hospital-based respiratory panel analyses—A comprehensive review. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, T.; Freeman, A.; Staples, K.J.; Wilkinson, T.M.A. Hidden in plain sight: The impact of human rhinovirus infection in adults. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Ogashiwa, H.; Nozaki, Y.; Ueda, T.; Nakajima, K.; Morosawa, M.; Doi, M.; Makino, M.; Takesue, Y. Judicious ending of isolation based on reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) cycle threshold only for patients with coronavirusdisease 2019 (COVID-19) requiring in-hospital therapy for longer than 20 days after symptom onset. J. Infect. Chemother. 2023, 29, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowrer, C.T.; Creager, H.; Cawcutt, K.; Birge, J.; Lyden, E.; Van Schooneveld, T.C.; Rupp, M.E.; Hewlett, A. Evaluation of cycle threshold values at deisolation. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021, 43, 794–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevik, M.; Tate, M.; Lloyd, O.; Maraolo, A.E.; Schafers, J.; Ho, A. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e13–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltola, V.; Waris, M.; Kainulainen, L.; Kero, J.; Ruuskanen, O. Virus shedding after human rhinovirus infection in children, adults and patients with hypogammaglobulinaemia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, E322–E327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Chan, P.K.S.; Hui, D.S.C.; Rainer, T.H.; Wong, E.; Choi, K.-W.; Lui, G.C.Y.; Wong, B.C.K.; Wong, R.Y.K.; Lam, W.-Y.; et al. Viral loads and duration of viral shedding in adult patients hospitalized with influenza. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Liao, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xiang, N.; Huai, Y.; Guo, X.; Zheng, Y.; van Doorn, H.R.; Farrar, J.; et al. Effectiveness of oseltamivir on disease progression and viral RNA shedding in patients with mild pandemic 2009 influenza A H1N1: Opportunistic retrospective study of medical charts in China. BMJ 2010, 341, c4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.-C.; Wang, L.; Eng, H.-L.; You, H.-L.; Chang, L.-S.; Tang, K.-S.; Lin, Y.-J.; Kuo, H.-C.; Lee, I.-K.; Liu, J.-W.; et al. Correlation of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Viral Load with Disease Severity and Prolonged Viral Shedding in Children. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, I.W.; Hung, I.F.; To, K.K.; Chan, K.-H.; Wong, S.S.Y.; Chan, J.F.; Cheng, V.C.; Tsang, O.T.; Lai, S.-T.; Lau, Y.-L.; et al. The Natural Viral Load Profile of Patients With Pandemic 2009 Influenza A(H1N1) and the Effect of Oseltamivir Treatment. Chest 2015, 137, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, S.A.; Farooq, M.U.; Bidari, V. Challenges associated with using cycle threshold (Ct) value of reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as a criteria for infectiousness of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients in india. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 1730–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathers, A.J. The practical challenges of making clinical use of the quantitative value for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral load across several dynamics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e4206–e4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfel, R.; Corman, V.M.; Guggemos, W.; Seilmaier, M.; Zange, S.; Müller, M.A.; Niemeyer, D.; Jones, T.C.; Vollmar, P.; Rothe, C.; et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 2020, 581, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, J.; Dust, K.; Funk, D.; Strong, J.E.; Alexander, D.; Garnett, L.; Boodman, C.; Bello, A.; Hedley, A.; Schiffman, Z.; et al. Predicting infectious severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from diagnostic samples. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2663–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, C.; Kanjilal, S.; Baker, M.; Klompas, M. Duration of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infectivity: When is it safe to discontinue isolation? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.Y.W.; Rozmanowski, S.; Pang, M.; Charlett, A.; Anderson, C.; Hughes, G.J.; Barnard, M.; Peto, L.; Vipond, R.; Sienkiewicz, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infectivity by viral load, S gene variants and demographic factors and the utility of lateral flow devices to prevent transmission. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Scola, B.; Le Bideau, M.; Andreani, J.; Hoang, V.T.; Grimaldier, C.; Colson, P.; Gautret, P.; Raoult, D. Viral RNA load as determined by cell culture as a management tool for discharge of SARS-CoV-2 patients from infectious disease wards. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorkman, K.K.; Saldi, T.K.; Lasda, E.; Bauer, L.C.; Kovarik, J.; Gonzales, P.K.; Fink, M.R.; Tat, K.L.; Hager, C.R.; Davis, J.C.; et al. Higher viral load drives infrequent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 transmission between asymptomatic residence hall roommates. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittain-Long, R.; Westin, J.; Olofsson, S.; Lindh, M.; Andersson, L.M. Prospective evaluation of a novel multiplex real-time PCR assay for detection of 15 respiratory pathogens-duration of symptoms significantly affects detection rate. J. Clin. Virol. 2010, 47, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| RESPIRATORY VIRUS | TOTAL N. PATIENTS | N. FEMALES (%) | N. MALES (%) | MEDIAN AGE (95% CI) | DEP. | N. PATIENTS /DEPARTMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | 379 | 170 (45) | 209 (65) | 81 (80–82) | GER | 237 |

| ICA | 43 | |||||

| INT | 66 | |||||

| DIV | 33 | |||||

| FLU | 321 | 161 (50) | 160 (50) | 79 (77–81) | GER | 152 |

| ICA | 46 | |||||

| INT | 94 | |||||

| DIV | 22 | |||||

| RSV | 126 | 74 (59) | 52 (41) | 83 (80–86) | GER | 74 |

| ICA | 16 | |||||

| REV | 4 | |||||

| INT | 26 | |||||

| DIV | 10 | |||||

| HRV | 52 | 25 (48) | 27 (52) | 79 (74–84) | GER | 28 |

| ICA | 9 | |||||

| INT | 11 | |||||

| DIV | 4 | |||||

| HMPV | 23 | 9 (39) | 14 (61) | 77 (71–83) | GER | 13 |

| ICA | 4 | |||||

| INT | 4 | |||||

| DIV | 2 | |||||

| PIV | 12 | 6 (50) | 6 (50) | 82 (68–95) | GER | 7 |

| ICA | 2 | |||||

| INT | 2 | |||||

| DIV | 1 | |||||

| ADV | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | DIV | 1 |

| TOTAL | 913 | 445 (49) | 468 (51) | 80 (79–81) |

| RESPIRATORY VIRUS | FU SAMPLING | N. SAMPLES | N. POSITIVE SAMPLES (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | Day 7 | 387 | 339 (88) |

| Day 14 | 154 | 121 (79) | |

| Day 21 | 38 | 33 (87) | |

| Day 28 | 11 | 11 (100) | |

| FLU | Day 7 | 335 | 153 (46) |

| RSV | Day 7 | 151 | 101 (67) |

| HRV | Day 7 | 63 | 49 (78) |

| HMPV | Day 7 | 26 | 20 (77) |

| PIV | Day 7 | 14 | 8 (57) |

| ADV | Day 7 | 1 | 1 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lemmens, S.; Janssen, K.; Nelis, T.; Elmahy, A.; Pierlet, N.; Oris, E.; Steensels, D. Redesigning Isolation Practices: Evaluation of a Comprehensive Protocol for Respiratory Virus Control Including Cycle Threshold (Ct) Value Dynamics. Viruses 2026, 18, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010040

Lemmens S, Janssen K, Nelis T, Elmahy A, Pierlet N, Oris E, Steensels D. Redesigning Isolation Practices: Evaluation of a Comprehensive Protocol for Respiratory Virus Control Including Cycle Threshold (Ct) Value Dynamics. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleLemmens, Stefanie, Kevin Janssen, Tine Nelis, Ahmed Elmahy, Noëlla Pierlet, Els Oris, and Deborah Steensels. 2026. "Redesigning Isolation Practices: Evaluation of a Comprehensive Protocol for Respiratory Virus Control Including Cycle Threshold (Ct) Value Dynamics" Viruses 18, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010040

APA StyleLemmens, S., Janssen, K., Nelis, T., Elmahy, A., Pierlet, N., Oris, E., & Steensels, D. (2026). Redesigning Isolation Practices: Evaluation of a Comprehensive Protocol for Respiratory Virus Control Including Cycle Threshold (Ct) Value Dynamics. Viruses, 18(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010040