Knowledge, Attitudes, and Biosecurity Practices Regarding African Swine Fever Among Small-Scale Pig Farmers in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Cambodia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Questionnaire Survey

2.3. Data Extraction and Scores

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

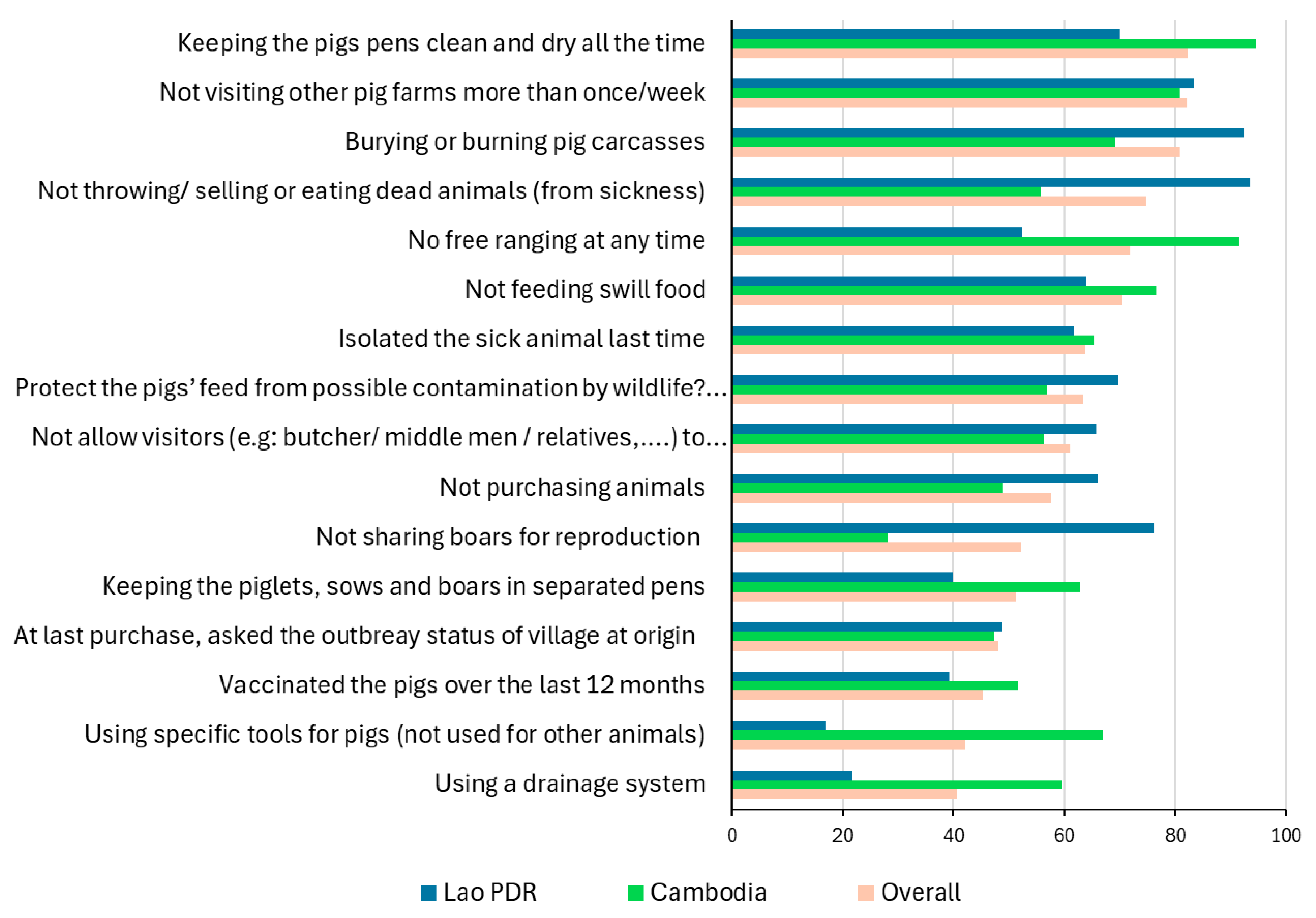

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code | Variable | Score |

|---|---|---|

| KS | Knowledge score | =(K1 + K2 + K3)/3 × 100 |

| K1 | Have you ever heard about ASF? | 0: No |

| 1: Yes | ||

| K2 | Which of the following clinical signs do you associate with ASF in pigs? | Sum divided by 19 (maximum amount of points possible) |

| K2.1 | Fever | 0: symptom not selected |

| K2.2 | Sudden death | 2: symptom selected |

| K2.3 | Presence of red loose skin coloration in the ventral abdomen, tips of ears, tail, or distal limb | |

| K2.4 | Blood in diarrhea/eyes/nose/urine | |

| K2.5 | Diarrhea | 0: symptom not selected |

| K2.6 | Higher mortality | 1: symptom selected |

| K2.7 | Joint swelling | |

| K2.8 | Coughing/dyspnoea | |

| K2.9 | Vomiting | |

| K2.10 | Loss appetite | |

| K2.11 | Abortion | |

| K2.12 | Increase in water intake and wallowing | |

| K2.13 | Seizures | |

| K2.14 | Swelling face/eyes | |

| K2.15 | Weakness | |

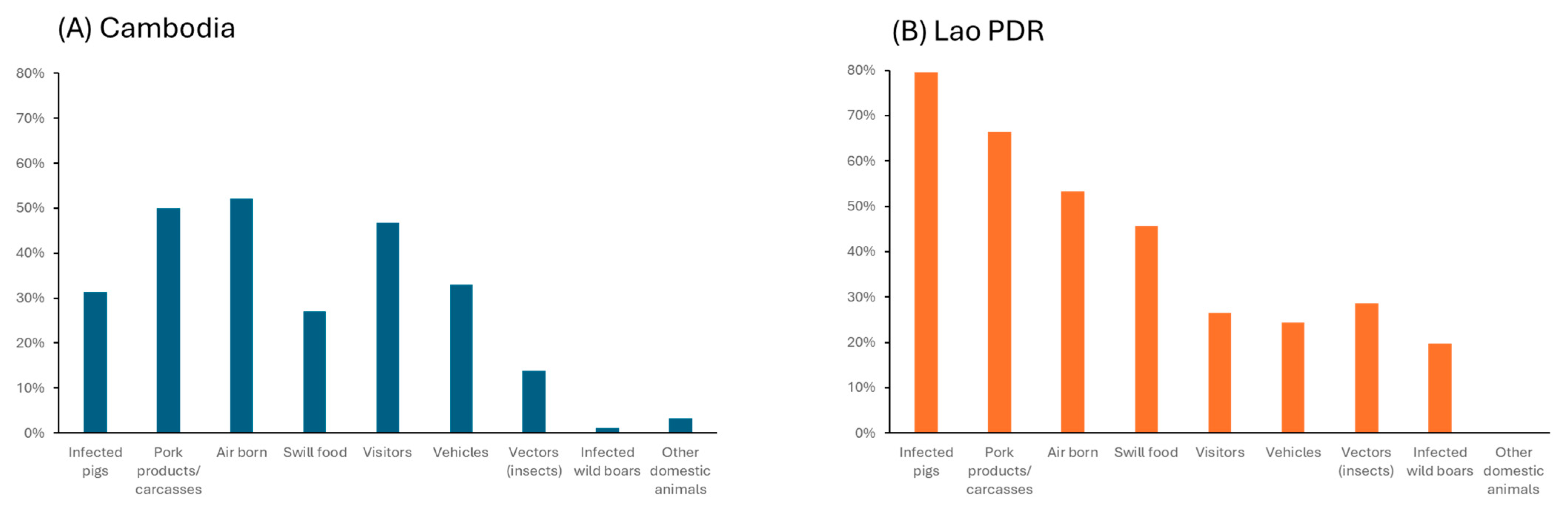

| K3 | By which of the following spread pathways can pigs be infected with ASF? | Sum of points divided by 9 (total amount of points possible) |

| K3.1 | Direct contact with an infected pig | 0–1 (if not selected/if selected) |

| K3.2 | Contact with pork product/carcass with contamination | 0–1 (if not selected/if selected) |

| K3.3 | Feeding of infected pig meat/swill/offal to pigs | 0–1 (if not selected/if selected) |

| K3.4 | Contact with infected wild boars | 0–1 (if not selected/if selected) |

| K3.5 | Visitors spreading the germs (e.g., pig traders) | 0–1 (if not selected/if selected) |

| K3.6 | Other domestic animals | 0–1 (if not selected/if selected) |

| K3.7 | Vehicles or equipment spreading the germs | 0–1 (if not selected/if selected) |

| K3.8 | Biting insects (ticks, fleas…) | 0–1 (if not selected/if selected) |

| K3.9 | Through the wind/air | 1–0 (if not selected/if selected) |

| K3.10 | None of the above | 0 if selected |

| RP | Risk perception score | 0 |

| (10 being the maximum number of points possible) | ||

| RP1 | 3.2 Have you ever experienced an African swine fever outbreak on your farm? | 0: No/1: Yes |

| RP2 | 3.7 Did any of your pigs die from ASF (after being sick or killed by local authorities) during the outbreak? | 1: No/2: Yes |

| RP3 | 3.6 Do you know anybody who has been affected by ASF? | 0: No/1: Yes |

| RP4 | Who do you know who has been affected by ASF? | 1: Another pig farmer/1.5: A relative/2: A friend |

| RP5 | Where these persons affected by ASF are keeping the pigs: | 1: in another village/2: in the same village |

| RP6 | 4.1 How strongly do you agree with the following statement? | (SumR P6.1 to RP6.4)/4 |

| RP6.1 | ASF is a very important disease | Score from 1 (do not agree at all) to 4 (fully agree) |

| RP6.2 | ASF is frequent in the country; if I do not take any measures, I will have an outbreak on my farm | |

| RP6.3 | My herd is not protected by vaccines and deworming | |

| RP6.4 | ASF is present in the Lao PDR | |

| PI | Perceived importance measures | =Sum (A2.1 to A2.25)/25 × 100 |

| (25 being the maximum number of points possible) | ||

| Which following measures regarding ASF prevention and control do you consider efficient/important? | ||

| PI.1 | Having a foot bath at the entrance | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.2 | Purchasing a new pig, keeping it in quarantine for at least 2 weeks before mixing it with the others | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.3 | Isolating sick pigs from the others | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.4 | Not allowing visitors (e.g., butcher/middlemen/relatives…) to enter the pig pen | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.5 | Asking visitors entering the farm/the pens to change their shoes | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.6 | Asking visitors entering the farm/the pens to change clothes | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.7 | Asking visitors entering the farm/the pens to disinfect their shoes | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.8 | Not visiting other pig farms frequently (>once/week) | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.9 | Protecting the pigs’ feed from possible contamination by wildlife (Stored in a closed place) | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.10 | Keeping the pigs’ pens clean and dry all the time | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.11 | Not feeding pigs with swill food | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.12 | Vaccinating the pigs every 6 months | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.13 | When purchasing pigs, ask if there is an ongoing outbreak in the community or farm from where you are buying the pig | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.14 | Keeping piglets, sows, and boars in separate pens | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.15 | Having a draining system | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.16 | Using specific tools (not used for other animals) to take care of the pigs (e.g., shovels…) | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.17 | Using specific tools for each of the pig pens (e.g., shovels…) | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.18 | Using specific clothes/footwear for taking care of pigs (Different from your daily life clothes/footwear) | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.19 | Using manure to fertilize crops | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.20 | Not sharing boars between pig farms (lending or borrowing) | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.21 | Using all replacement stocks that are produced and grown within your farm/not buying pigs from outside | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.22 | Disinfection pig pen | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.23 | Mosquito net/spray | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.24 | Personal hygiene | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| PI.25 | Use artificial intelligence | 0: Not selected/1: selected |

| BSc | Biosecurity score (BSc) | =(P1 × P1.1 × P1.2 + P2 + P3.1 + P4 + P5 + P6)/41 × 100 |

| P1 | Penning | 0: No, Full-time free-ranging/scavenging |

| 1: Part-time housed/fenced/penning | ||

| 2: Yes, full-time housed/fenced/penning | ||

| P1.1 | Pen flooring | 0: soil |

| 1: wooden floor | ||

| 2: cemented/concrete floor | ||

| P1.2 | Pen walls | 0: not precise/none |

| 1: wooden fences | ||

| 2: steel fences | ||

| 3: Solid walls | ||

| P2 | What are you feeding your pigs with now? | 0: scavenging/swill food |

| 1: Local feed | ||

| 2: Commercial feed | ||

| Remark: if several, the one with the lowest score was attributed | ||

| P3 | If you observe clinical signs of ASF in your pig herd, what do you do? Action | 0: I would sell/eat/give the pigs as soon as possible to avoid losing too much |

| 1: I would treat the pigs/I would wait a few days to see if the pigs improve or not | ||

| 2: I would take additional BS measures /I would isolate the pig/I would bury/burn the carcass | ||

| P4 | If you suspect there is an ASF outbreak in your farm/village, what would you do: | 0: Nothing/Wait a few days before reporting it to avoid a false report/have the time to sell the healthy pigs and avoid too much losses/self treatment/vaccination |

| 1: Report it as soon as possible, even if it might be a false case | ||

| 2: Protect my farm by additional BS | ||

| P5 | Carcass disposal (pigs that died and are not consumed) | =(P5.1 + P5.2)/3 |

| P5.1 | Do you have a carcass disposal point (CDP)? | 0: No/1: Yes |

| P5.2 | How do you dispose of carcasses? | 0: Throw it into the bush/Sell it off/No dead pigs |

| 1: Burning/Burying | ||

| 2: Burying + Use of chemical | ||

| P6 | Which of the following practices are you implementing? | =SOMME (P6.1 to 6.2&6.21) |

| P6.1 | 1. Do you have a foot bath at the entrance of your pens | 0: No/Yes |

| P6.2 | 2. The last time you purchased a new pig, did you keep it in quarantine for at least 2 weeks before mixing them with the others? | 1: Yes/No |

| P6.3 | 3. The last time one of your animals was sick, did you isolate it from the others? | N/A: not applicable |

| P6.4 | 4. Do you allow visitors (e.g., butcher/middlemen/relatives…) to enter the pig pen? | |

| P6.5 | 5. Do you ask visitors entering the farm/the pens to change footwear? | |

| P6.6 | 6. Do you ask visitors entering the farm/the pens to change clothes? | |

| P6.7 | 7. Do you ask visitors entering the farm/the pens to disinfect their shoes? | |

| P6.8 | 8. Do you visit other pig farms frequently (>once/week) | |

| P6.9 | 9. Do you protect the pigs’ feed from possible contamination by wildlife? (Stored in a closed place) | |

| P6.10 | 10. Do you keep the pigs’ pens clean and dry all the time? | |

| P6.11 | 11. Do you ever feed your pigs with swill food? | |

| P6.12 | 12. Did you vaccinate your pigs over the last 12 months? | |

| P6.13 | 13. The last time you purchased pigs, did you ask if there was an ongoing outbreak in the community or farm from where you are buying the pigs? | |

| P6.14 | 14. Are the piglets, sows, and boars kept in separate pens? | |

| P6.15 | 15. Do you use a drainage system? | |

| P6.16 | 16. Do you use specific tools when taking care of your pigs (e.g., shovels…)? | |

| Meaning tools that you do not use for other animals | ||

| P6.17 | 17. Do you use specific tools only for each pig pen (e.g., shovels…)? | |

| P6.18 | 18. Do you wear specific clothes/footwear for taking care of pigs? | |

| (Different from your daily life clothes/footwear) | ||

| P6.19 | 19. Do you use pig manure for fertilizing crops? | |

| P6.20 | 20. Do you share boars with other farms (lend out or borrow)? | |

| P6.21 | 21. Are all replacement stocks produced and grown within your farm? | |

| P6.22 | 5.8 Is there any other measure you are taking to prevent or control diseases that have not been listed? | 0: No or measure not relevant/1: Yes and relevant |

References

- Blome, S.; Franzke, K.; Beer, M. African swine fever—A review of current knowledge. Virus Res. 2020, 287, 198099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.K.; Stahl, K.; Jori, F.; Vial, L.; Pfeiffer, D.U. African Swine Fever Epidemiology and Control. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2020, 8, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrith, M.; Bastos, A.D.; Etter, E.M.C.; Beltrán-Alcrudo, D. Epidemiology of African swine fever in Africa today: Sylvatic cycle versus socio-economic imperatives. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Kawaguchi, N.; Bosch, J.; Aguilar-Vega, C.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M. What can we learn from the five-year African swine fever epidemic in Asia? Front. Veter.-Sci. 2023, 10, 1273417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.Y.; Matsumoto, N.; Siengsanan-Lamont, J.; Young, J.R.; Khounsy, S.; Douangneun, B.; Thepagna, W.; Phommachanh, P.; Blacksell, S.D.; Ward, M.P. Spatiotemporal Drivers of the African Swine Fever Epidemic in Lao PDR. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2023, 2023, 5151813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Organization Animal Health. African Swine Fever (ASF)—Report N°20; World Organization Animal Health: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/03/report-20-current-situation-asf.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Sothyra, T. ASF situation in Cambodia. In Proceedings of the Second Meeting of the Standing Group on African Swine Fever, Tokyo, Japan, 31 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Suriya, V. African Swine Fever (ASF) Laos Situation Update. 2019. Available online: https://rr-asia.woah.org/app/uploads/2019/12/5-laos.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Mighell, E.; Ward, M.P. African Swine Fever spread across Asia, 2018–2019. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 2722–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denstedt, E.; Porco, A.; Hwang, J.; Nga, N.T.T.; Ngoc, P.T.B.; Chea, S.; Khammavong, K.; Milavong, P.; Sours, S.; Osbjer, K.; et al. Detection of African swine fever virus in free-ranging wild boar in Southeast Asia. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 2669–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costard, S.; Zagmutt, F.J.; Porphyre, T.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Small-scale pig farmers’ behavior, silent release of African swine fever virus and consequences for disease spread. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.C.; Bui, N.T.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Ngo, T.N.T.; Van Nguyen, C.; Nguyen, L.M.; Nouhin, J.; Karlsson, E.; Padungtod, P.; Pamornchainavakul, N.; et al. An African swine fever vaccine-like variant with multiple gene deletions caused reproductive failure in a Vietnamese breeding herd. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keonouchanh, S.; Dengkhounxay, T. Pig Production and Pork Quality Improvement in Lao Pdr and Rural Development (NAFRI) Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) Lao PDR Background. 2017. Available online: https://www.angrin.tlri.gov.tw/meeting/2017TwVn/2017TwVn_p37-42.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’connor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.J.; O’connor, D.; Curran, J. Theories of behaviour change synthesised into a set of theoretical groupings: Introducing a thematic series on the theoretical domains framework. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.; Marzano, M.; Danady, N.; O’Brien, L. Theories and Models of Behaviour and Behaviour Change; Forest Research: Surrey, UK, 2012. Available online: https://cdn.forestresearch.gov.uk/2022/02/behaviour_review_theory.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Renault, V.; Damiaans, B.; Humblet, M.F.; Ruiz, S.J.; García Bocanegra, I.; Brennan, M.L.; Casal, J.; Petit, E.; Pieper, L.; Simoneit, C.; et al. Cattle farmers’ perception of biosecurity measures and the main predictors of behaviour change: The first European-wide pilot study. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 3305–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richens, I.; Houdmont, J.; Wapenaar, W.; Shortall, O.; Kaler, J.; O’connor, H.; Brennan, M. Application of multiple behaviour change models to identify determinants of farmers’ biosecurity attitudes and behaviours. Prev. Veter-Med. 2018, 155, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garforth, C.; Rehman, T.; McKemey, K.; Tranter, R.; Cooke, R.; Yates, C.; Park, J.; Dorward, P. Improving the design of knowledge transfer strategies by understanding farmer attitudes and behaviour. J. Farm Manag. 2004, 12, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- van Winsen, F.; de Mey, Y.; Lauwers, L.; Van Passel, S.; Vancauteren, M.; Wauters, E. Determinants of risk behaviour: Effects of perceived risks and risk attitude on farmer’s adoption of risk management strategies. J. Risk Res. 2016, 19, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics. Census of Agriculture Cambodia 2023. National Report on Final Census Results. 2025. Available online: https://www.nis.gov.kh/nis/Agriculture%20Census/2-CAC2023-Main%20Report_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- GDAHP. Report Summarizing the Results of Animal Health and Animal Production Work in 2023 and Raising Work Goals for 2024; GDAHP: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Cambodia Inclusive Livestock Value Chains Project, Project Information Document; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Saegerman, C.; Humblet, M.-F.; Leandri, M.; Gonzalez, G.; Heyman, P.; Sprong, H.; L’hostis, M.; Moutailler, S.; Bonnet, S.I.; Haddad, N.; et al. First Expert Elicitation of Knowledge on Possible Drivers of Observed Increasing Human Cases of Tick-Borne Encephalitis in Europe. Viruses 2023, 15, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willson, V.L. Critical Values of the Rank-Biserial Correlation Coefficient. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1976, 36, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djellata, N.; Yahimi, A.; Hanzen, C.; Saegerman, C. Survey of the prevalence of bovine abortions and notification and management practices by veterinary practitioners in Algeria. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz. 2020, 39, 947–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, N.; Siengsanan-Lamont, J.; Halasa, T.; Young, J.R.; Ward, M.P.; Douangngeun, B.; Theppangna, W.; Khounsy, S.; Toribio, J.L.; Bush, R.D.; et al. The impact of African swine fever virus on smallholder village pig production: An outbreak investigation in Lao PDR. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 2897–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, N.; Siengsanan-Lamont, J.; Halasa, T.; Young, J.R.; Ward, M.P.; Douangngeun, B.; Theppangna, W.; Khounsy, S.; Toribio, J.-A.L.M.L.; Bush, R.D.; et al. Retrospective investigation of the 2019 African swine fever epidemic within smallholder pig farms in Oudomxay province, Lao PDR. Front. Veter.-Sci. 2023, 10, 1277660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, N.; Ward, M.P.; Halasa, T.; Schemann, K.; Khounsy, S.; Douangngeun, B.; Thepagna, W.; Phommachanh, P.; Siengsanan-Lamont, J.; Young, J.R.; et al. Novel estimation of African swine fever transmission parameters within smallholder villages in Lao P.D.R. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 56, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszyk, H.; Franzke, K.; Breithaupt, A.; Deutschmann, P.; Pikalo, J.; Carrau, T.; Blome, S.; Sehl-Ewert, J. The Role of Male Reproductive Organs in the Transmission of African Swine Fever—Implications for Transmission. Viruses 2021, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penrith, M.-L.; van Heerden, J.; Pfeiffer, D.U.; Oļševskis, E.; Depner, K.; Chenais, E. Innovative Research Offers New Hope for Managing African Swine Fever Better in Resource-Limited Smallholder Farming Settings: A Timely Update. Pathogens 2023, 12, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Risk Perception | =(RP1 × RP2 + RP3 × R4 × RP5 + RP6)/10 × 100 (10 Being the Maximum of Points Possible) |

|---|---|

| RP1—Have you ever experienced an ASF outbreak on your farm? | 0: No/1: Yes |

| RP2—Did any of your pigs die from ASF (after being sick or culled by local authorities) during the outbreak? | 1: No/2: Yes |

| RP3—Do you know anybody who has been affected by ASF? | 0: No/1: Yes |

| RP4—If yes, who? | 1: Another pig farmer 1.5: A relative 2: A friend |

| RP5—If yes, where are these persons? | 1: in another village 2: in the same village |

| RP6—How strongly do you agree with the following statement? (score from 1 to 4) | (Sum RP6.1 to RP6.4)/4 |

| RP6.1—ASF is a very important disease | 1 strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree |

| RP6.2—ASF is frequent in the country; if I do not take any measures, I will have an outbreak in my farm | 2 strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree |

| RP6.3—My herd is not protected by vaccines and deworming | 3 strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree |

| RP6.4—ASF is present in the Lao PDR | 4 strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree |

| Cambodia (N = 188) | The Lao PDR (N = 283) | Overall (N = 471) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of women | 68% | 47% | 56% |

| Age range | 18–80 | 22–73 | 18–80 |

| Education level | |||

| Illiterate | 19 | 45 | 64 |

| Primary school | 93 | 118 | 211 |

| Secondary school | 55 | 85 | 140 |

| Higher education | 21 | 35 | 56 |

| African Swine Fever exposure | |||

| Heard of ASF | 92% | 66% | 77% |

| Experienced ASF | 63% | 52% | 56% |

| Cambodia (N = 188) | The Lao PDR (N = 283) | Overall (N = 471) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Herd size | 1–110 | 1–1200 | 1–1200 |

| Age range | 18–80 | 22–73 | 18–80 |

| Pig importance | |||

| Main source of income | 22% | 30% | 27% |

| Second source of income | 50% | 27% | 36% |

| Third source of income | 21% | 17% | 19% |

| Additional/not a source of income | 6% | 27% | 14% |

| Years of pig farming | |||

| <1 year | 6% | 20% | 15% |

| >10 years | 17% | 24% | 21% |

| >2–5 years | 17% | 12% | 14% |

| >5–10 years | 60% | 43% | 50% |

| Cambodia (N = 188) | The Lao PDR (N = 283) | Overall (N = 471) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASF is an important disease | 73% | 70% | 71% |

| ASF is not present in Lao/Cambodia | 15% | 30% | 24% |

| ASF is frequent; I need to take measures to prevent an outbreak on my farm | 92% | 66% | 76% |

| My herd is not protected by vaccination and deworming | 55% | 53% | 54% |

| Practice | Cambodia (N = 188) | The Lao PDR (N = 283) | Overall (N = 471) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free ranging (full or partial time) | 9% | 48% | 32% |

| Scavenging/feeding swill food | 23% | 43% | 35% |

| Not reporting outbreak suspicions | 66% | 70% | 69% |

| Selling/eating, or giving away sick pigs | 31% | 7% | 17% |

| Not applying a two-week quarantine to purchased pigs | 85% | 61% | 70% |

| Not isolating sick pigs | 35% | 38% | 37% |

| Allowing visitors | 44% | 34% | 38% |

| Throwing/selling or eating carcasses | 44% | 6% | 21% |

| Sharing boars for mating | 72% | 24% | 43% |

| Total | 188 | 283 | 471 |

| Explanatory Variable | Variable Importance (Scale from 0 to 100) |

|---|---|

| Education | 100 |

| Perceived benefits of biosecurity measures | 99.74 |

| Herd size | 83.54 |

| Risk perception | 80.31 |

| The main purpose of pig farming | 64 |

| Importance of pigs for livelihoods | 61.78 |

| Knowledge of African swine fever | 60.21 |

| Age of the farmer | 40.2 |

| Type of pigs | 38.73 |

| Gender | 0.47 |

| (A) Importance of the three mental constructs on the biosecurity scores | ||||||||

| Explanatory Variable | Lao PDR Importance over the BS Score (Scale from 0 to 100) | Cambodia Importance over the BS Score (Scale from 0 to 100) | ||||||

| Perceived benefits of biosecurity measures | 100 | 73.43 | ||||||

| Risk perception | 82.26 | 24.85 | ||||||

| Knowledge of African Swine Fever | 72.82 | 12.14 | ||||||

| (B) Importance of the farm and farmers profiles on the biosecurity score and the mental constructs | ||||||||

| Lao PDR | Cambodia | |||||||

| Importance over (Scale from 0 to 100) | Importance over (Scale from 0 to 100) | |||||||

| Explanatory variable | BS Score | Knowledge | Risk Perception | Benefits Perception | BS Score | Knowledge | Risk Perception | Benefits Perception |

| Education | 91.64 | 97.26 | 41.35 | 55.62 | 57.68 | 100 | ||

| Herd size | 54.93 | 100 | 46.73 | 100 | 67.68 | 1.67 | 63.33 | |

| Importance of pigs for livelihoods | 39.42 | 46.89 | 97.77 | 1.31 | 15.14 | 79.58 | 100 | |

| Main purpose of pig farming | 29.97 | 4.83 | 100 | 61 | 100 | |||

| Type of pigs | 27.41 | 57.51 | 67.64 | 100 | 61.76 | |||

| Age of the farmer | 17 | 100 | 1.88 | 1 | 0.01 | |||

| Gender | 2.43 | 63.96 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Renault, V.; Masson, A.; Xaphokame, P.; Phommasack, O.; Sear, B.; Ven, S.; Saegerman, C. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Biosecurity Practices Regarding African Swine Fever Among Small-Scale Pig Farmers in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Cambodia. Viruses 2026, 18, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010034

Renault V, Masson A, Xaphokame P, Phommasack O, Sear B, Ven S, Saegerman C. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Biosecurity Practices Regarding African Swine Fever Among Small-Scale Pig Farmers in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Cambodia. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleRenault, Véronique, Ariane Masson, Paeng Xaphokame, Outhen Phommasack, Borin Sear, Samnang Ven, and Claude Saegerman. 2026. "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Biosecurity Practices Regarding African Swine Fever Among Small-Scale Pig Farmers in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Cambodia" Viruses 18, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010034

APA StyleRenault, V., Masson, A., Xaphokame, P., Phommasack, O., Sear, B., Ven, S., & Saegerman, C. (2026). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Biosecurity Practices Regarding African Swine Fever Among Small-Scale Pig Farmers in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Cambodia. Viruses, 18(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010034