The Role of mTOR Inhibitors in COVID-19 Outcomes Among Heart Transplant Recipients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASA | Acetylsalicylic acid |

| CNI | Calcineurin inhibitor |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFA | Heart Failure Association |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| MMF | Mycophenolate mofetil |

| OHT | Orthotopic heart transplantation |

| PTLD | Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder |

References

- Rzhanyi, M.; Pechenenko, A.; Alcocer, J.; Sandoval Martínez, E.; Quintana, E. Cardiac retransplantation. Multimed. Man. Cardiothorac. Surg. MMCTS 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscano, G.; Bottio, T.; Gambino, A.; Bagozzi, L.; Guariento, A.; Bortolussi, G.; Gallo, M.; Tarzia, V.; Gerosa, G. Orthotopic heart transplantation: The bicaval technique. Multimed. Man. Cardiothorac. Surg. MMCTS 2015, 2015, mmv035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCartney, S.L.; Patel, C.; Del Rio, J.M. Long-term outcomes and management of the heart transplant recipient. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2017, 312, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Ugidos, P.; Barge-Caballero, E.; Gómez-López, R.; Paniagua-Martin, M.J.; Barge-Caballero, G.; Couto-Mallón, D.; Solla-Buceta, M.; Iglesias-Gil, C.; Aller-Fernández, V.; González-Barbeito, M.; et al. In-hospital postoperative infection after heart transplantation: Risk factors and development of a novel predictive score. Transpl. Infect. Dis. Off. J Transplant Soc. 2019, 214, e13104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.; Nourse, J.; Hall, S.; Green, M.; Griffiths, L.; Gandhi, M.K. Immunodeficiency-associated lymphomas. Blood Rev. 2008, 225, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosangi, B.; Rubinowitz, A.N.; Irugu, D.; Gange, C.; Bader, A.; Cortopassi, I. COVID-19 ARDS: A review of imaging features and overview of mechanical ventilation and its complications. Emerg. Radiol. 2022, 291, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, S.C.; Singh, M. Multi-organ damage by covid-19: Congestive (cardio-pulmonary) heart failure, and blood-heart barrier leakage. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 1891–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascella, M.; Rajnik, M.; Aleem, A.; Dulebohn, S.C.; Di Napoli, R. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19); StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska, E.; Michalak, S.S. Covid-19—Disease Caused By Sars-Cov-2 Infection—Vaccine And New Therapies Research Development. Adv. Microbiol. 2020, 593, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abasian, L.; Jafari, F.; SeyedAlinaghi, S.; Yazdi, N.A.; Daraei, M.; Ahmadinejad, N.; Ghiasvand, F.; Khalili, H.; Seifi, A.; Meidani, M.; et al. The comparison of clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings in immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients with COVID-19: A case-control study. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2023, 114, e806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz-Menger, J.; Collini, V.; Gröschel, J.; Adler, Y.; Brucato, A.; Christian, V.; Ferreira, V.M.; Gandjbakhch, E.; Heidecker, B.; Kerneis, M.; et al. 2025 ESC Guidelines for the management of myocarditis and pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2025, 46, 3952–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przytuła, N.; Podolec, J.; Przewłocki, T.; Podolec, P.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. Inflammasomes as Potential Therapeutic Targets to Prevent Chronic Active Viral Myocarditis-Translating Basic Science into Clinical Practice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.H.; Wang, Y. Inflammatory Pathways in Coronary Artery Disease: Which Ones to Target for Secondary Prevention? Cells 2025, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudasama, Y.V.; Zaccardi, F.; Gillies, C.L.; Razieh, C.; Yates, T.; Kloecker, D.E.; Rowlands, A.V.; Davies, M.J.; Islam, N.; Seidu, S.; et al. Patterns of multimorbidity and risk of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: An observational study in the U.K. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 211, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naesens, M.; Kuypers, D.R.J.; Sarwal, M. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2009, 42, 481–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrini, S.; Moretta, A.; Biassoni, R.; Nicolin, A.; Moretta, L. Cyclosporin-A inhibits IL-2 production by all human T-cell clones having this function, independent of the T4/T8 phenotype or the coexpression of cytolytic activity. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1986, 381, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clipstone, N.A.; Crabtree, G.R. Identification of calcineurin as a key signalling enzyme in T-lymphocyte activation. Nature 1992, 357, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekierka, J.J.; Hung, S.H.; Poe, M.; Lin, C.S.; Sigal, N.H. A cytosolic binding protein for the immunosuppressant FK506 has peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity but is distinct from cyclophilin. Nature 1989, 341, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaud, G.; Legendre, C.; Terzi, F. AKT/mTORC pathway in antiphospholipid-related vasculopathy: A new player in the game. Lupus 2015, 243, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoni, M.; Massari, F.; Cascinu, S. Prophylactic use of mTOR inhibitors and other immunosuppressive agents in heart transplant patients. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 121, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampaktsis, P.N.; Doulamis, I.P.; Asleh, R.; Makri, E.; Kalamaras, I.; Papastergiopoulos, C.; Emfietzoglou, M.; Drosou, A.; Eynde, J.V.D.; Alnsasra, H.; et al. Characteristics, Predictors, and Outcomes of Early mTOR Inhibitor Use After Heart Transplantation: Insights from the UNOS Database. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e025507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewanowski, K.; Drozd, R.; Broś, U.; Droździk, M. Nephropathy induced by calcineurin inhibitors in patients after heart transplantation as one of the important problems of modern transplantation. Ren. Dis. Transplant. Forum 2013, 64, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Asante-Korang, A.; Carapellucci, J.; Krasnopero, D.; Doyle, A.; Brown, B.; Amankwah, E. Conversion from calcineurin inhibitors to mTOR inhibitors as primary immunosuppressive drugs in pediatric heart transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2017, 31, e13054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, R.N.; Metcalfe, M.S.; Nicholson, M.L. Rapamycin in transplantation: A review of the evidence. Kidney Int. 2001, 591, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Tao, T.; Li, H.; Zhu, X. mTOR signaling pathway and mTOR inhibitors in cancer: Progress and challenges. Cell Biosci. 2020, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, S.M.; Kormos, R.L.; Landreneau, R.J.; Kawai, A.; Gonzalez-Cancel, I.; Hardesty, R.L.; Hattler, B.G.; Griffith, B.P. Solid tumors after heart transplantation: Lethality of lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1995, 60, 1623–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlakonda, L.; Pasupuleti, M.; Reddanna, P. Role of PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Wnt Signaling Pathways in Transition of G1-S Phase of Cell Cycle in Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chi, H. mTOR and lymphocyte metabolism. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2013, 25, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrassy, J.; Hoffmann, V.S.; Rentsch, M.; Stangl, M.; Habicht, A.; Meiser, B.; Fischereder, M.; Jauch, K.-W.; Guba, M. Is cytomegalovirus prophylaxis dispensable in patients receiving an mTOR inhibitor-based immunosuppression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation 2012, 94, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.; Alvey, N.; Bowman, L.; Schulte, J.; Segovia, M.C.; McDermott, J.; Te, H.S.; Kapila, N.; Levine, D.J.; Gottlieb, R.L.; et al. Consensus recommendations for use of maintenance immunosuppression in solid organ transplantation: Endorsed by the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, American Society of Transplantation, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2022, 42, 599–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, M.L.; Pirofski, L. Mycophenolate mofetil: Effects on cellular immune subsets, infectious complications, and antimicrobial activity. Transpl. Infect. Dis. Off. J. Transplant Soc. 2009, 11, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, H.-T.; Wu, X.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Shih, C.-M.; Lin, Y.-W.; Lin, F.-Y. The Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Infection, and Application of Immunosuppressive Agents in Kidney Transplant Recipients Suffering from COVID-19. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Requião-Moura, L.R.; Modelli de Andrade, L.G.; de Sandes-Freitas, T.V.; Cristelli, M.P.; Viana, L.A.; Nakamura, M.R.; Garcia, V.D.; Manfro, R.C.; Simão, D.R.; Almeida, R.A.M.B.; et al. The Mycophenolate-based Immunosuppressive Regimen Is Associated with Increased Mortality in Kidney Transplant Patients with COVID-19. Transplantation 2022, 106, e441–e451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canossi, A.; Panarese, A.; Savino, V.; Del Beato, T.; Pisani, F. COVID-19 in Kidney Transplant Recipients: What Did We Understand After Three Years Since the Pandemic Outbreak in Kidney Transplant Recipients? Curr. Transplant. Rep. 2023, 10, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhao, R.; Cai, T.; Beaulieu-Jones, B.; Seyok, T.; Dahal, K.; Yuan, Q.; Xiong, X.; Bonzel, C.-L.; Fox, C.; et al. Temporal Trends in Clinical Evidence of 5-Year Survival Within Electronic Health Records Among Patients With Early-Stage Colon Cancer Managed With Laparoscopy-Assisted Colectomy vs Open Colectomy. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022, 56, e2218371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile, M.S.; Cavalli, E.; McCubrey, J.; Hernández-Bello, J.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F.; Fagone, P.; Nicoletti, F. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: A potential pharmacological target in COVID-19. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Byrareddy, S.N. Rapamycin as a potential repurpose drug candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 331, 109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velleca, A.; Shullo, M.A.; Dhital, K.; Azeka, E.; Colvin, M.; DePasquale, E.; Farrero, M.; García-Guereta, L.; Jamero, G.; Khush, K.; et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. Off. Publ. Int. Soc Heart Transplant. 2023, 42, e1–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.; Vautier, M.; Allenbach, Y.; Zahr, N.; Benveniste, O.; Funck-Brentano, C.; Salem, J.-E. Sirolimus and mTOR Inhibitors: A Review of Side Effects and Specific Management in Solid Organ Transplantation. Drug Saf. 2019, 42, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soefje, S.A.; Karnad, A.; Brenner, A.J. Common toxicities of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors. Target Oncol. 2011, 6, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askanase, A.D.; Khalili, L.; Buyon, J.P. Thoughts on COVID-19 and autoimmune diseases. Lupus Sci. Med. 2020, 7, e000396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients With Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2020, 71, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrazzano, G.; Rubino, V.; Palatucci, A.T.; Giovazzino, A.; Carriero, F.; Ruggiero, G. An Open Question: Is It Rational to Inhibit the mTor-Dependent Pathway as COVID-19 Therapy? Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam, B.S.; Morris, R.S.; Bramante, C.T.; Puskarich, M.; Zolfaghari, E.J.; Lotfi-Emran, S.; Ingraham, N.E.; Charles, A.; Odde, D.J.; Tignanelli, C.J. mTOR inhibition in COVID-19: A commentary and review of efficacy in RNA viruses. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 934, 1843–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, G.; Sharma, A.; Ramaiah, A.; Sen, C.; Purkayastha, A.; Kohn, D.B.; Parcells, M.S.; Beck, S.; Kim, H.; Bakowski, M.A.; et al. Antiviral drug screen identifies DNA-damage response inhibitor as potent blocker of SARS-CoV-2 replication. Cell Rep. 2021, 351, 108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appelberg, S.; Gupta, S.; Svensson Akusjärvi, S.; Ambikan, A.T.; Mikaeloff, F.; Saccon, E.; Végvári, Á.; Benfeitas, R.; Sperk, M.; Ståhlberg, M.; et al. Dysregulation in Akt/mTOR/HIF-1 signaling identified by proteo-transcriptomics of SARS-CoV-2 infected cells. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 91, 1748–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omarjee, L.; Janin, A.; Perrot, F.; Laviolle, B.; Meilhac, O.; Mahe, G. Targeting T-cell senescence and cytokine storm with rapamycin to prevent severe progression in COVID-19. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 216, 108464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaeberlein, T.L.; Green, A.S.; Haddad, G.; Hudson, J.; Isman, A.; Nyquist, A.; Rosen, B.S.; Suh, Y.; Zalzala, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Evaluation of off-label rapamycin use to promote healthspan in 333 adults. GeroScience 2023, 455, 2757–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, G.B.; Tunbridge, M.J.; Chai, C.S.; Hope, C.M.; Yeow, A.E.L.; Salehi, T.; Singer, J.; Shi, B.; Masavuli, M.G.; Mekonnen, Z.A.; et al. Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Inhibitors and Vaccine Response in Kidney Transplant Recipients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2025, 36, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinchera, B.; Spirito, L.; Buonomo, A.R.; Foggia, M.; Carrano, R.; Salemi, F.; Schettino, E.; Papa, F.; La Rocca, R.; Crocetto, F.; et al. mTOR Inhibitor Use Is Associated With a Favorable Outcome of COVID-19 in Patients of Kidney Transplant: Results of a Retrospective Study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 852973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Cohort (N = 352) | Patients Without mTOR Inhibitors (N = 264) | Patients with mTOR Inhibitors (N = 88) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 incidence, n (%) | 126 (35.8) | 97 (36.7) | 29 (33) | 0.52 |

| COVID-19 hospitalization, n (%) | 20 (5.7) | 17 (6.4) | 3 (3.4) | 0.29 |

| COVID-19-related death, n (%) | 13 (3.7) | 10 (3.8) | 3 (3.4) | 0.87 |

| COVID-19 vaccinated, n (%) | 276 (78.4) | 202 (76.5) | 74 (84.1) | 0.13 |

| All-cause mortality, n (%) | 50 (14.2) | 31 (11.7) | 19 (21.6) | 0.02 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 303 (86.1) | 227 (86) | 76 (86.4) | 0.93 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2, n (%) | 192 (54.5) | 146 (55.3) | 46 (52.3) | 0.62 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 283 (80.4) | 214 (81.1) | 69 (78.4) | 0.59 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 89 (25.3) | 68 (25.8) | 21 (23.9) | 0.72 |

| Age (years) | 61 (48–67) | 61 (48–67) | 60.5 (47–67.5) | 0.86 |

| Creatinine level (mg/dL) | 116 (92.8–148) | 117 (94–147) | 116 (89.5–148) | 0.54 |

| COVID-19 antibodies level (BAU/mL) | 30.9 (0.4–250) | 22.2 (0.4–250) | 70.48 (2.11–250) | 0.06 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.2 (24–30.1) | 26.2 (24.1–30.1) | 26.28 (23.9–29.9) | 0.92 |

| Cardiac allograft vasculopathy, n (%) | 70 (19.9) | 56 (21.2) | 14 (15.9) | 0.28 |

| Follow-up time since OHT (days) | 3457 (1903–6005) | 3175 (1658–5866) | 4912 (2436.5–6913) | <0.001 |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

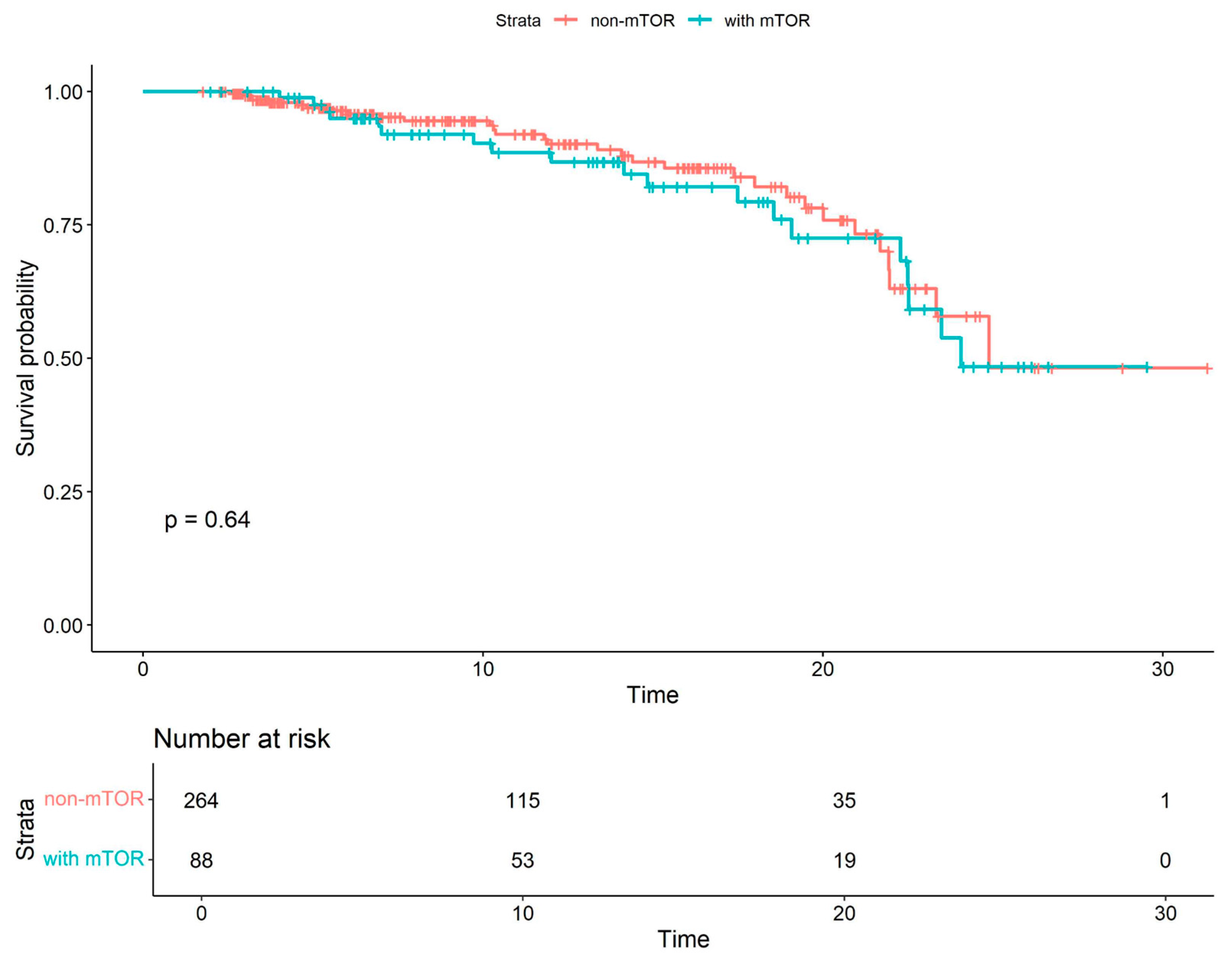

| Combined mTOR all-cause mortality | 1.15 | 0.64–2.05 | 0.64 |

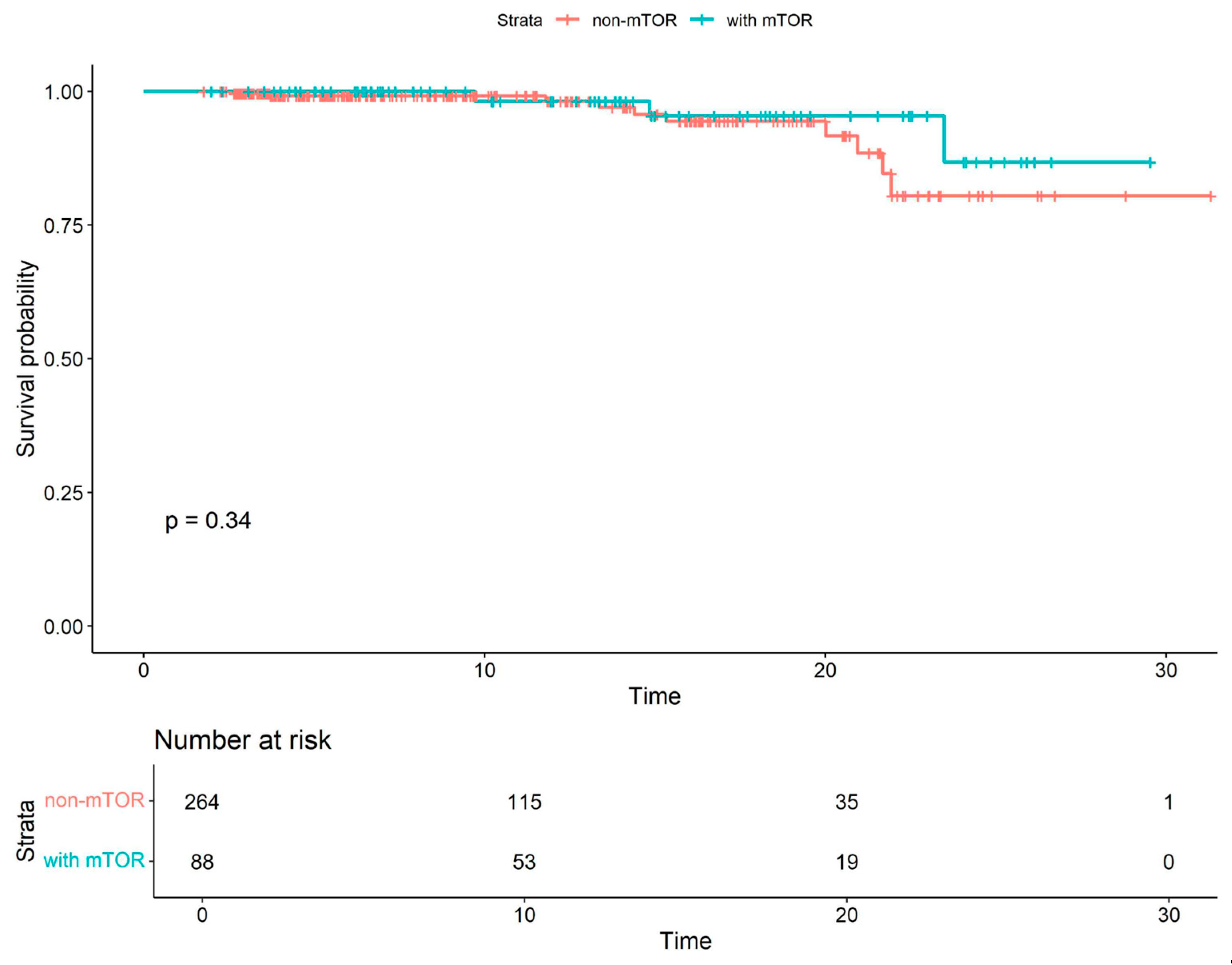

| Combined mTOR COVID-19-related mortality | 0.54 | 0.15–1.98 | 0.35 |

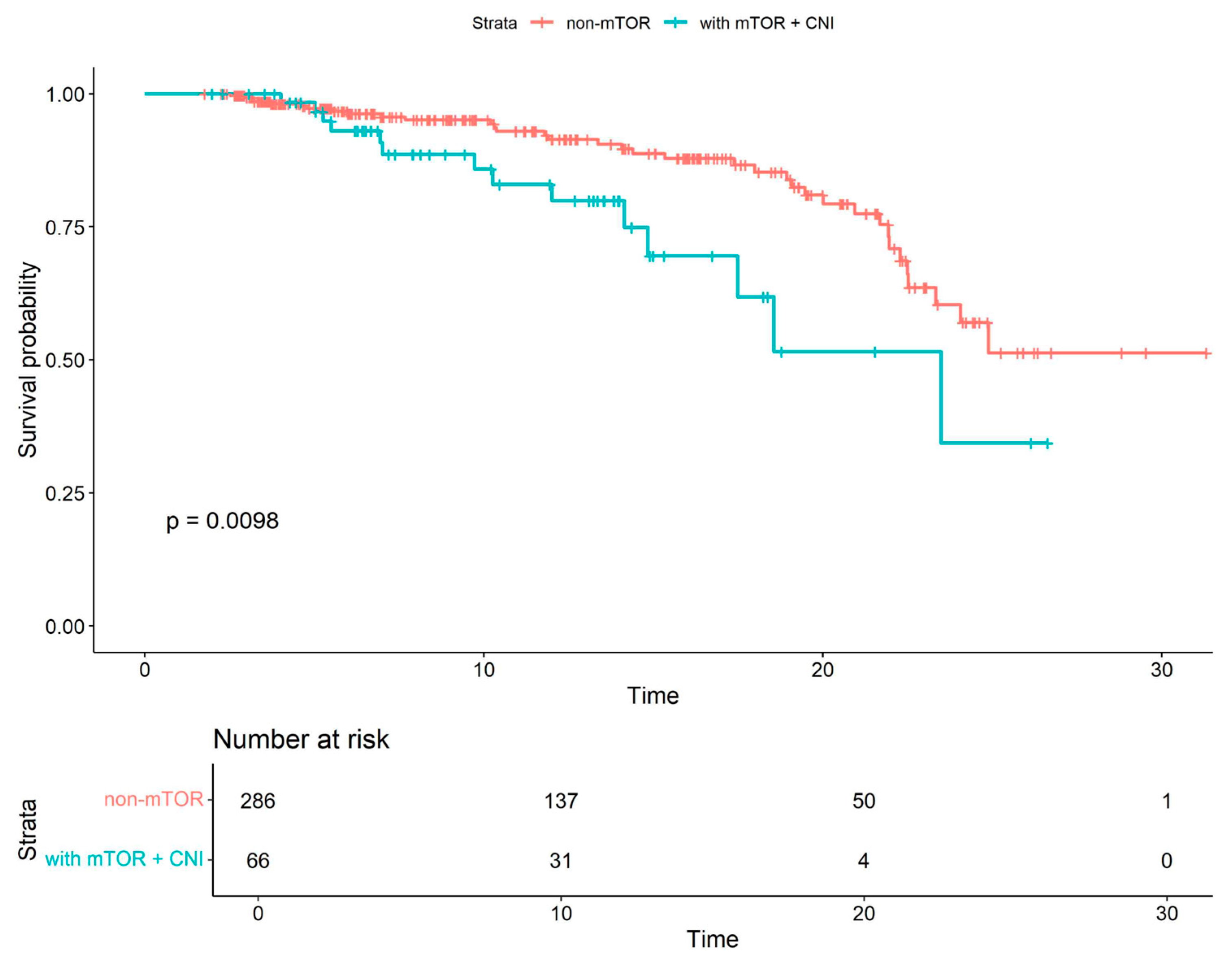

| mTOR+CNI all-cause mortality | 2.24 | 1.2–4.2 | 0.01 |

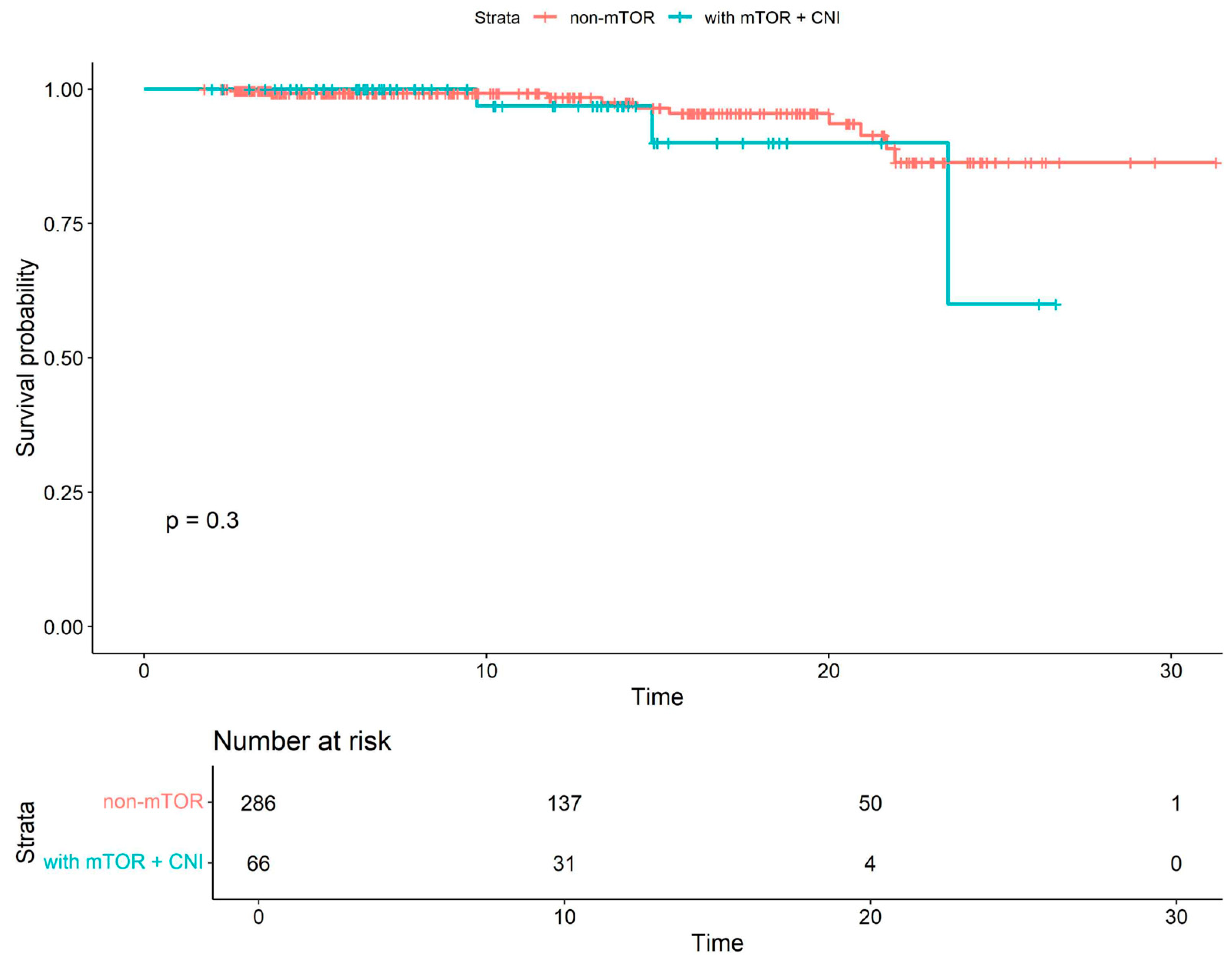

| mTOR+CNI COVID-19-related mortality | 1.97 | 0.53–7.3 | 0.31 |

| mTOR CNI-free all-cause mortality * | 0.43 | 0.17–1.1 | 0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kuczaj, A.; Warwas, S.; Tyrka, M.; Skotnicki, B.; Szymecki, D.; Jewuła, O.; Pawlak, S.; Przybyłowski, P.; Hrapkowicz, T. The Role of mTOR Inhibitors in COVID-19 Outcomes Among Heart Transplant Recipients. Viruses 2026, 18, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010029

Kuczaj A, Warwas S, Tyrka M, Skotnicki B, Szymecki D, Jewuła O, Pawlak S, Przybyłowski P, Hrapkowicz T. The Role of mTOR Inhibitors in COVID-19 Outcomes Among Heart Transplant Recipients. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuczaj, Agnieszka, Szymon Warwas, Mikołaj Tyrka, Błażej Skotnicki, Daniel Szymecki, Oliwia Jewuła, Szymon Pawlak, Piotr Przybyłowski, and Tomasz Hrapkowicz. 2026. "The Role of mTOR Inhibitors in COVID-19 Outcomes Among Heart Transplant Recipients" Viruses 18, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010029

APA StyleKuczaj, A., Warwas, S., Tyrka, M., Skotnicki, B., Szymecki, D., Jewuła, O., Pawlak, S., Przybyłowski, P., & Hrapkowicz, T. (2026). The Role of mTOR Inhibitors in COVID-19 Outcomes Among Heart Transplant Recipients. Viruses, 18(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010029