Three Staphylococcus Bacteriophages Isolated from Swine Farm Environment in Quebec, Canada, Infecting S. chromogenes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains Used in This Study

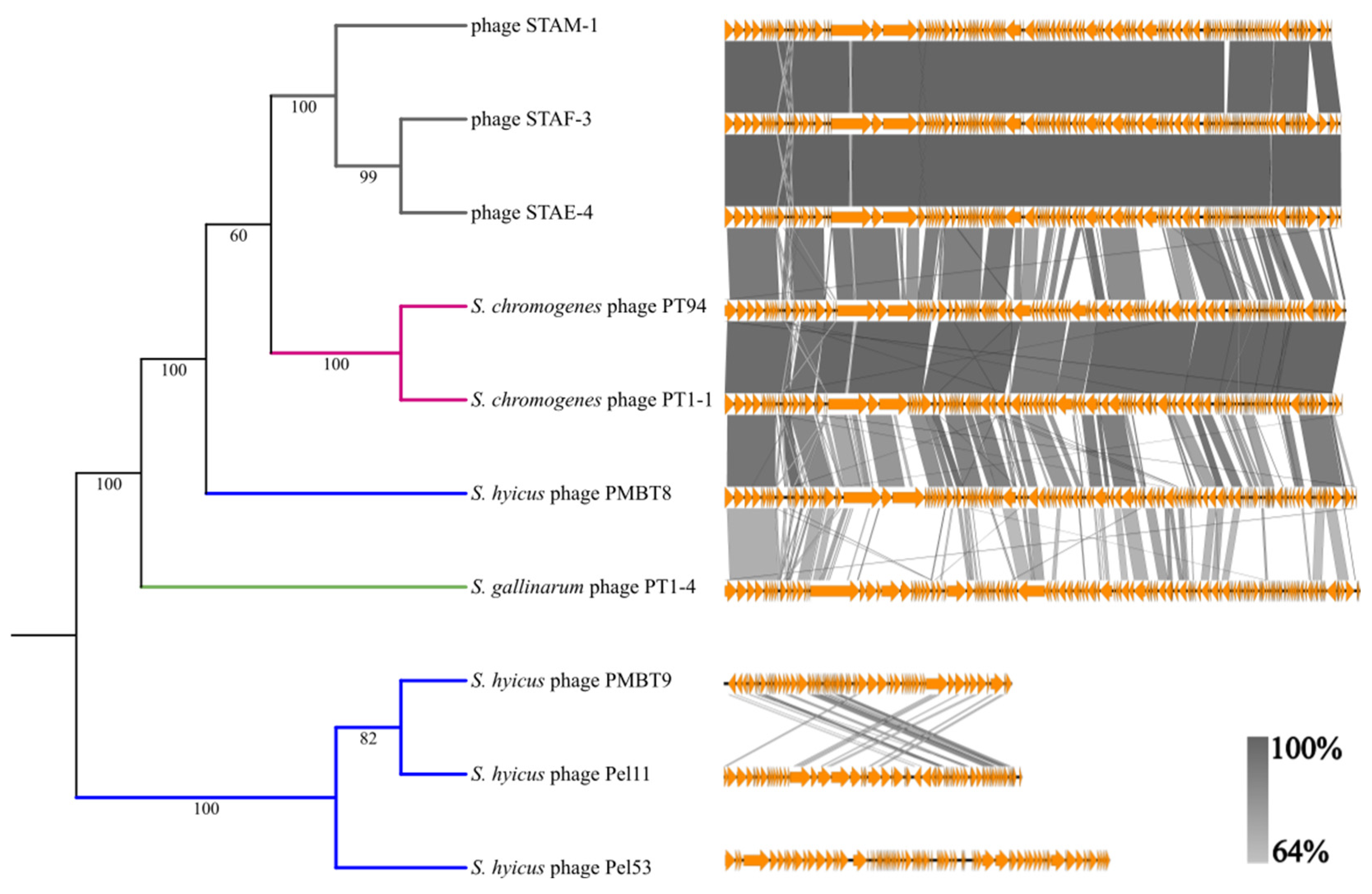

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Phage Isolation

2.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.6. Randomly Amplified Polymorphic DNA- PCR

2.7. DNA-Extraction for Genome Sequencing

2.8. Genomic Analysis

2.8.1. Phage Genome Assembly and Protein Annotation

2.8.2. Genomic Comparison

2.8.3. Identification of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors

2.9. Host Range and Efficiency of Plating

2.10. Phage Stability and One-Step Growth Curve

2.11. Phage Adsorption

3. Results

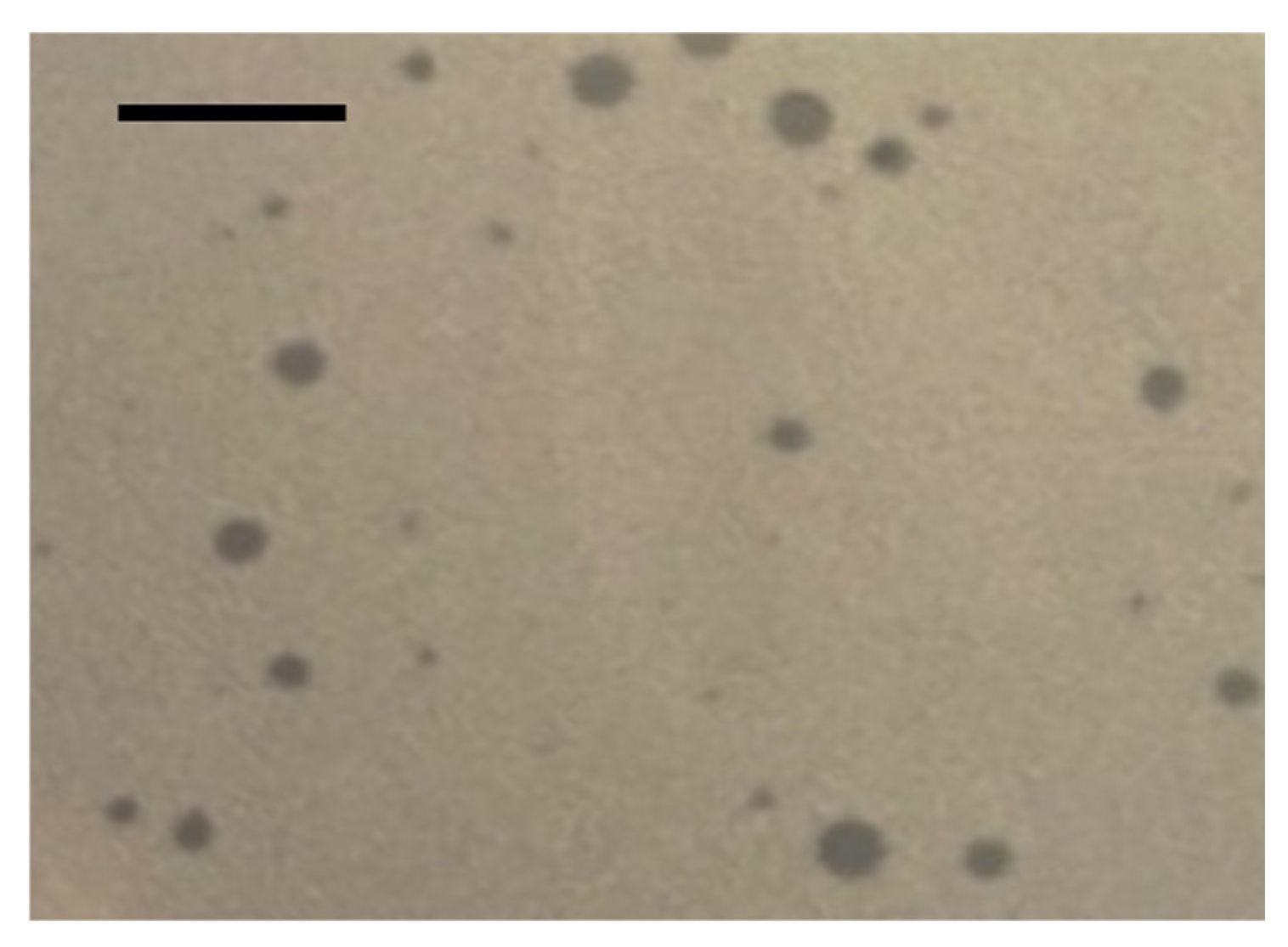

3.1. Phage Isolation

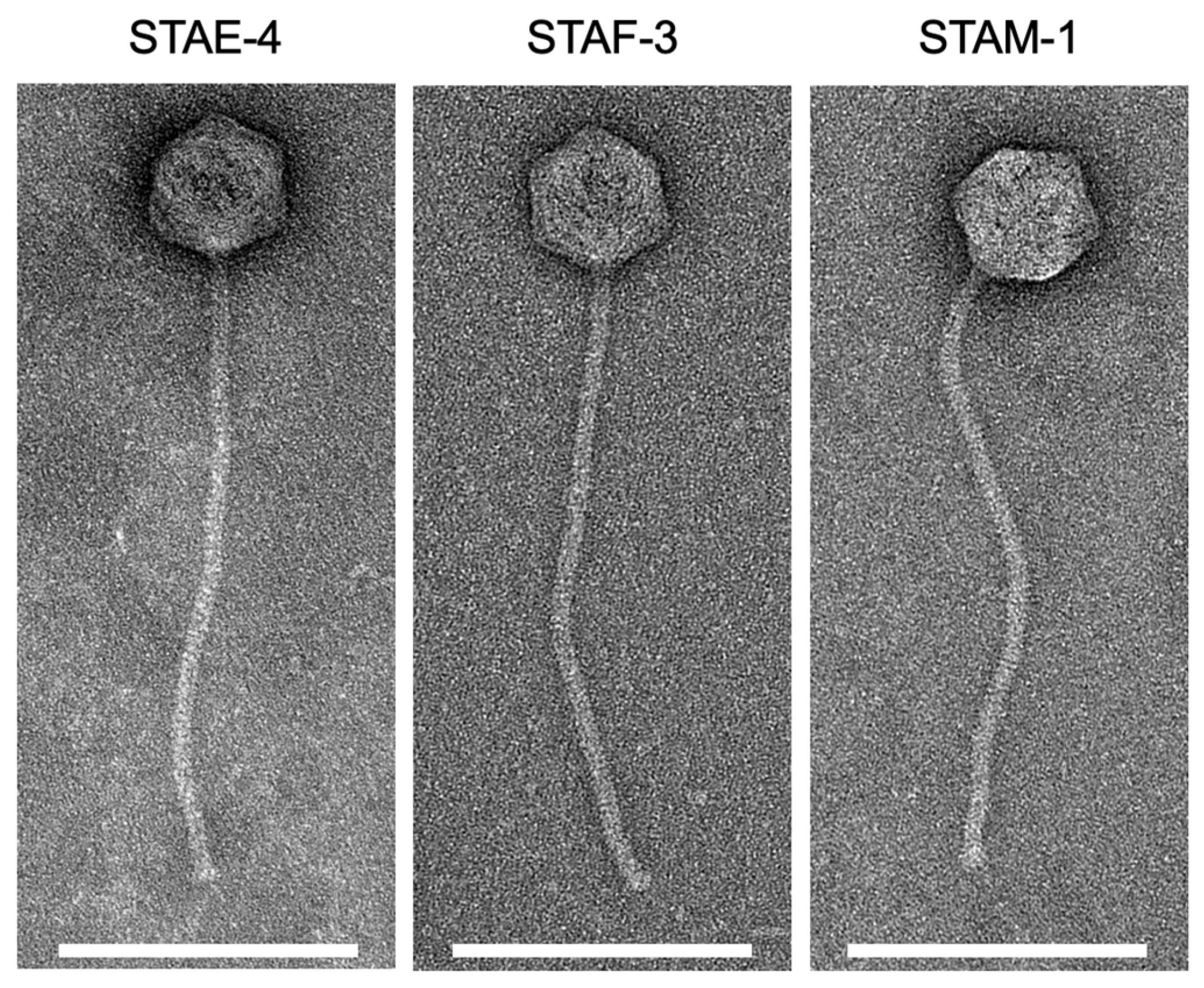

3.2. Phage Morphology

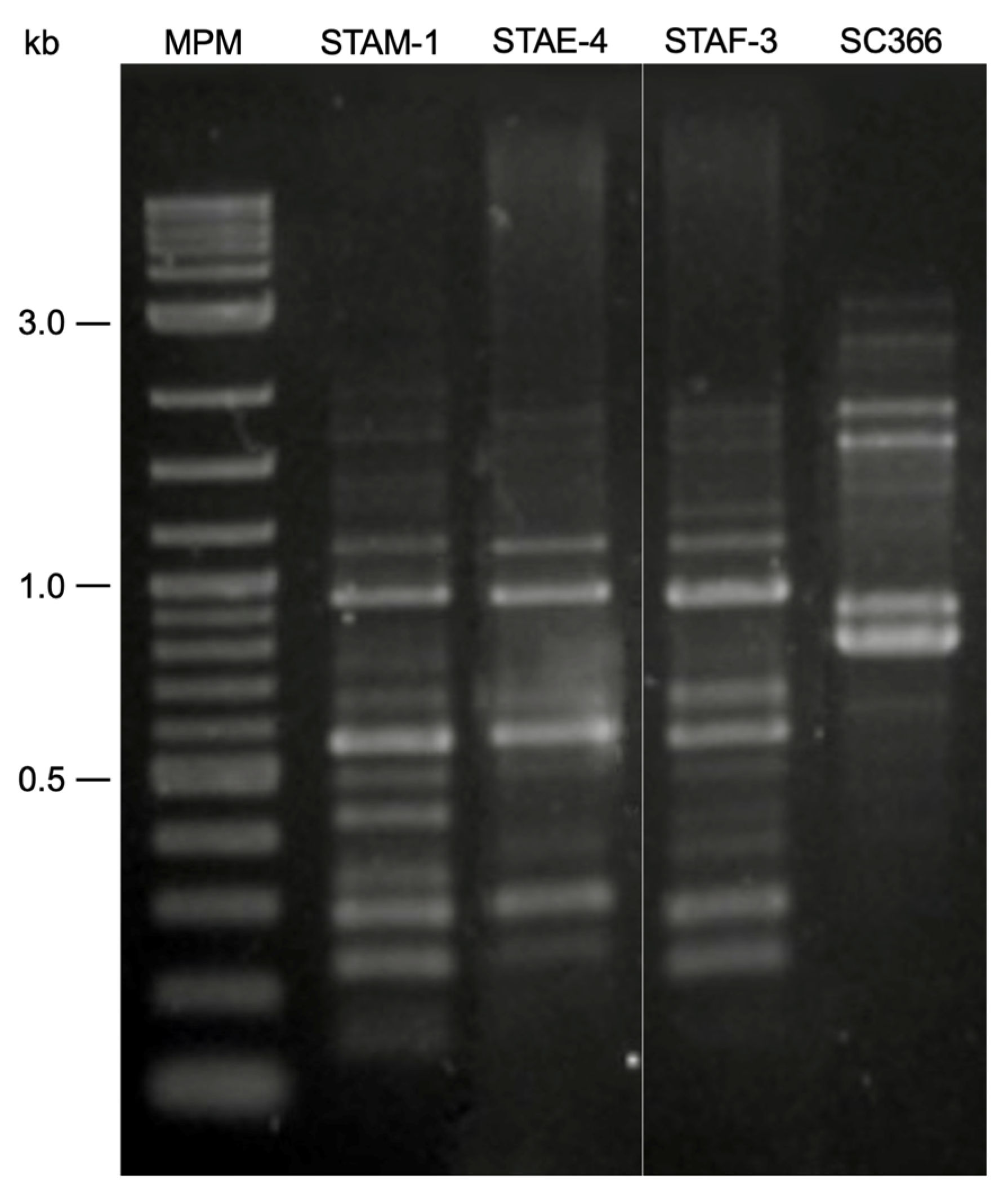

3.3. RAPD-PCR

3.4. Genomic Analysis

3.5. Host Range and Efficiency of Plating

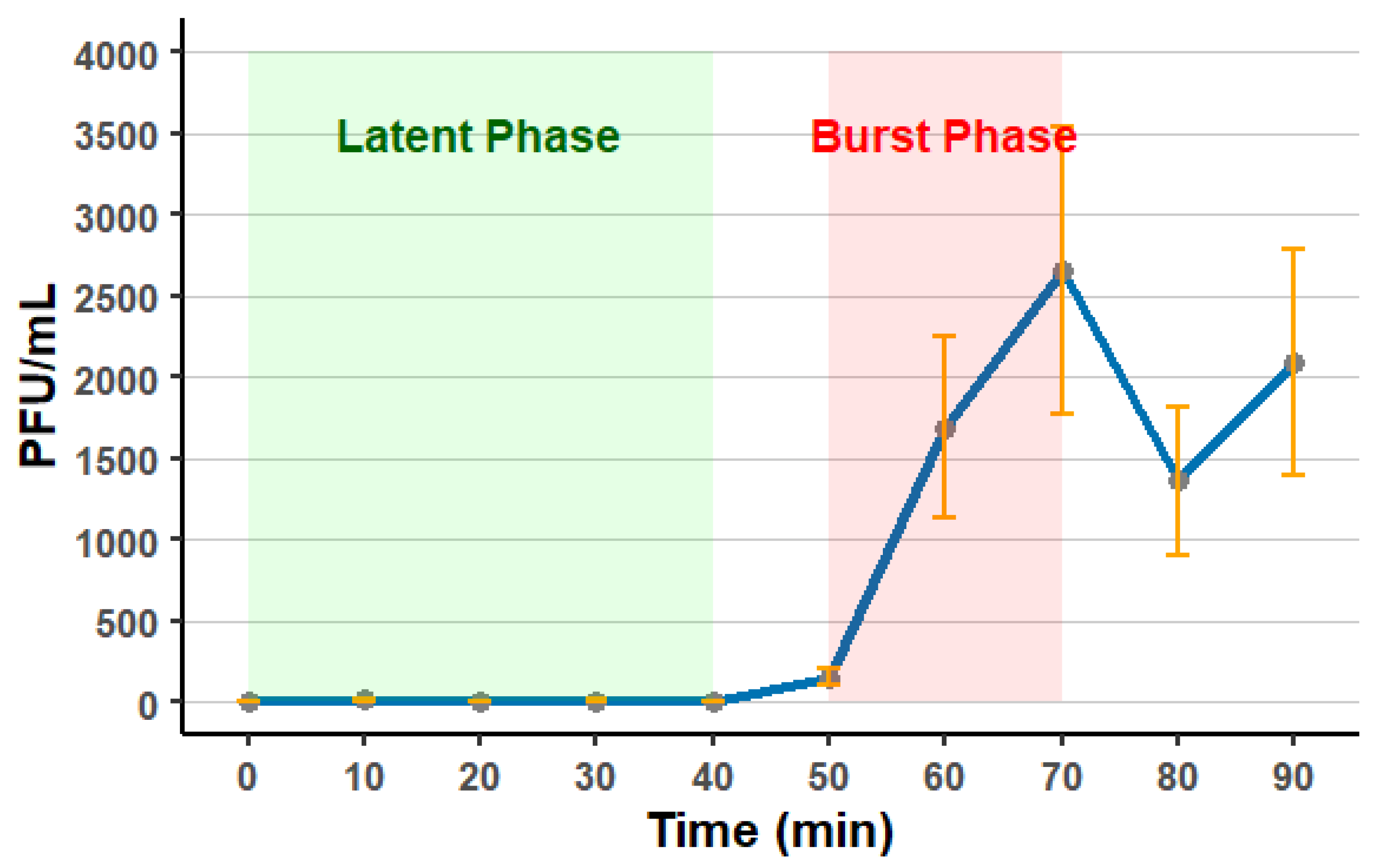

3.6. Phage Stability and One-Step Growth Curve

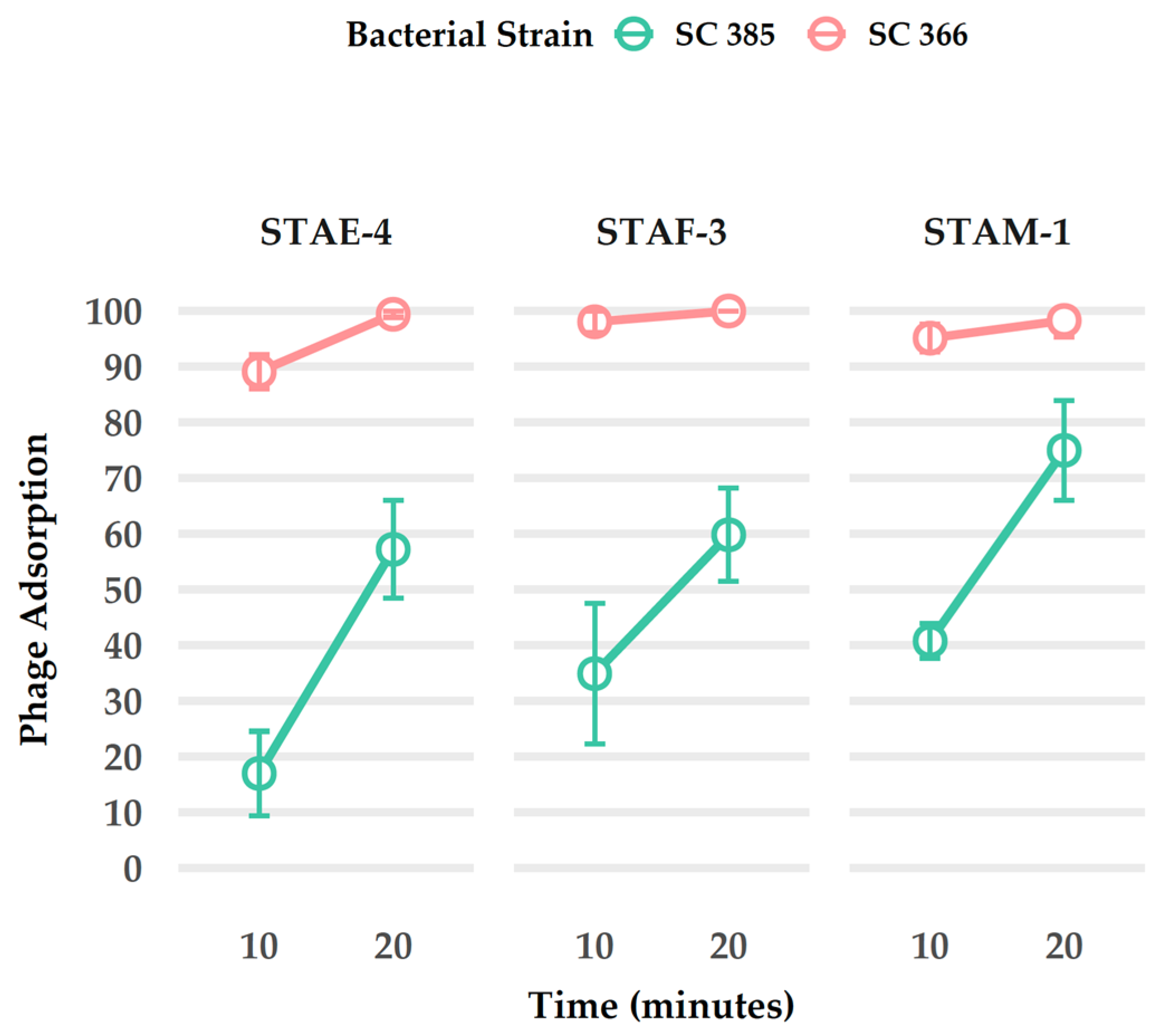

3.7. Adsorption

4. Discussion

4.1. Phage Isolation, Morphology and Stability

4.2. Phage Infects S. chromogenes, Not S. hyicus

4.3. The Uniqueness of S. Hyicus Strain SC366

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foster, A.P. Staphylococcal skin disease in livestock. Vet. Dermatol. 2012, 23, 342-e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarestrup, F.M.; Duran, C.O.; Burch, D.G. Antimicrobial resistance in swine production. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2008, 9, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenakis, I.; Boyen, F.; Haesebrouck, F.; Maes, D.G. Autogenous vaccination reduces antimicrobial usage and mortality rates in a herd facing severe exudative epidermitis outbreaks in weaned pigs. Vet. Rec. 2018, 182, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, B.; Corney, B.; Wagner, T. Importance of Staphylococcus hyicus ssp hyicus as a cause of arthritis in pigs up to 12 weeks of age. Aust. Vet. J. 1996, 73, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truswell, A.; Laird, T.; Blinco, J.; Pang, S.; Jordan, D.; Hampson, D.; Adsett, S.; Abraham, R.; Abraham, S. Exudative epidermitis-causing Staphylococcus hyicus: Insights and education for industry optimisation. Anim. Sci. Proc. 2023, 14, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.R. Exudative epidermitis in pigs. In Merck Veterinary Manual; Merck & Co., Inc.: Rahway, NJ, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.merckvetmanual.com/integumentary-system/exudative-epidermitis/exudative-epidermitis-in-pigs (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Devriese, L.; Hajek, V.; Oeding, P.; Meyer, S.; Schleifer, K. Staphylococcus hyicus (Sompolinsky 1953) comb. nov. and Staphylococcus hyicus subsp. chromogenes subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1978, 28, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, V.; Devriese, L.; Mordarski, M.; Goodfellow, M.; Pulverer, G.; Varaldo, P. Elevation of Staphylococcus hyicus subsp. chromogenes (Devriese et al., 1978) to species status: Staphylococcus chromogenes (Devriese et al., 1978) comb. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1986, 8, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naushad, S.; Barkema, H.W.; Luby, C.; Condas, L.A.; Nobrega, D.B.; Carson, D.A.; De Buck, J. Comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of bovine non-aureus staphylococci species based on whole-genome sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, L.O.; Ahrens, P.; Daugaard, L.; Bille-Hansen, V. Exudative epidermitis in pigs caused by toxigenic Staphylococcus chromogenes. Vet. Microbiol. 2005, 105, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MAPAQ. Bilan Réseau Porcin 2022; Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation du Québec (MAPAQ): Québec, QC, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://cdn-contenu.quebec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/agriculture-pecheries-alimentation/sante-animale/surveillance-controle/raizo/reseau-porcin/RA_bilan_reseau_porcin_2022_MAPAQ.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Aarestrup, F.M.; Wegener, H.C.; Collignon, P. Resistance in bacteria of the food chain: Epidemiology and control strategies. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2008, 6, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Friendship, R.M.; Poljak, Z.; Weese, J.S.; Dewey, C.E. An investigation of exudative epidermitis (greasy pig disease) and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Staphylococcus hyicus and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical cases. Can. Vet. J. 2013, 54, 139–144. Available online: https://europepmc.org/articles/PMC3552588 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Moreno, A.M.; Moreno, L.Z.; Poor, A.P.; Matajira, C.E.C.; Moreno, M.; Gomes, V.T.d.M.; da Silva, G.F.R.; Takeuti, K.L.; Barcellos, D.E. Antimicrobial resistance profile of Staphylococcus hyicus strains isolated from Brazilian swine herds. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagné-Thivierge, C.; Gauthier, M.-L.; Denicourt, M.; Lambert, M.; Vincent, A.T.; Charette, S.J. Diversity of tet(L)-bearing plasmids found in Eastern Canadian Staphylococcus hyicus isolates from swine. Genome 2025, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desiree, K.; Mosimann, S.; Ebner, P. Efficacy of phage therapy in pigs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, A.G.; Lindsay, J.A.; Read, T.D. Determinants of phage host range in Staphylococcus species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e00209-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, A.; Atterbury, R.J. Veterinary use of bacteriophage therapy in intensively-reared livestock. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutter, E.; Goldman, E. Introduction to bacteriophages. In Practical Handbook of Microbiology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 683–702. [Google Scholar]

- Chhanda, M.S.; François, N.R.L.; Auclert, L.Z.; Derome, N. Cultivation of brook charr Salvelinus fontinalis: The challenges of disease control and the promise of microbial ecology management. Aquac. Res. 2024, 2024, 2279222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, H.C. Development of a phage typing system for Staphylococcus hyicus. Res. Microbiol. 1993, 144, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, A.; Teranishi, H.; Kawano, J.; Kimura, S. Phage patterns of Staphylococcus hyicus subsp. hyicus isolated from chickens, cattle and pigs. Ser. A Med. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Virol. Parasitol. 1987, 265, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, J.; Shimizu, A.; Kimura, S. Bacteriophage typing of Staphylococcus hyicus subsp hyicus isolated from pigs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1983, 44, 1476–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrzik, K.; Sovová, L. New lytic and new temperate Staphylococcus hyicus phages. Virus Genes 2025, 61, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetens, J.; Sprotte, S.; Thimm, G.; Wagner, N.; Brinks, E.; Neve, H.; Hölzel, C.S.; Franz, C.M. First molecular characterization of Siphoviridae-like bacteriophages infecting Staphylococcus hyicus in a case of exudative epidermitis. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 653501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné-Thivierge, C.; Vincent, A.T.; Paquet, V.E.; Gauthier, M.-L.; Denicourt, M.; Lambert, M.-È.; Charette, S.J. Draft genome sequences of four Staphylococcus hyicus strains, SC302, SC304, SC306, and SC310, isolated from swine from Eastern Canada. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2023, 12, e00626-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, N.; Rojas, M.I.; Cruz, G.N.F.; Hung, S.-H.; Rohwer, F.; Barr, J.J. Phage on tap–a quick and efficient protocol for the preparation of bacteriophage laboratory stocks. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Rueden, C.T.; Hiner, M.C.; Eliceiri, K.W. The ImageJ ecosystem: An open platform for biomedical image analysis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2015, 82, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charette, S.J.; Cosson, P. Preparation of genomic DNA from Dictyostelium discoideum for PCR analysis. Biotechniques 2004, 36, 574–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, N.; Paquet, V.E.; Marcoux, P.-É.; Alain, C.-A.; Paquet, M.F.; Moineau, S.; Charette, S.J. MQM1, a bacteriophage infecting strains of Aeromonas salmonicida subspecies salmonicida carrying Prophage 3. Virus Res. 2023, 334, 199165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, D.; Martín-Platero, A.M.; Rodríguez, A.; Martínez-Bueno, M.; García, P.; Martínez, B. Typing of bacteriophages by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)-PCR to assess genetic diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011, 322, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Shovill Github. 2016. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/shovill (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Bouras, G.; Nepal, R.; Houtak, G.; Psaltis, A.J.; Wormald, P.-J.; Vreugde, S. Pharokka: A fast scalable bacteriophage annotation tool. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, G.; Grigson, S.R.; Mirdita, M.; Heinzinger, M.; Papudeshi, B.; Mallawaarachchi, V.; Green, R.; Kim, S.R.; Mihalia, V.; Psaltis, A.J.; et al. Protein Structure Informed Bacteriophage Genome Annotation with Phold. Nucleic Acids Res. 2026, 54, gkaf1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Tong, X.; Zhou, T.; Li, M.; Barkema, H.W.; Nobrega, D.B.; Kastelic, J.P.; Xu, C.; Han, B. Biological and genomic characterization of 4 novel bacteriophages isolated from sewage or the environment using non-aureus Staphylococci strains. Vet. Microbiol. 2024, 294, 110133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, L.; Zheng, R. Isolation and characterization of a lytic Staphylococcus aureus phage WV against Staphylococcus aureus biofilm. Intervirology 2021, 64, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.L.; Xie, B.B.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, X.L.; Zhou, B.C.; Zhou, J.; Oren, A.; Zhang, Y.Z. A proposed genus boundary for the prokaryotes based on genomic insights. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 2210–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölzer, M. POCP-nf: An automatic Nextflow pipeline for calculating the percentage of conserved proteins in bacterial taxonomy. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, R.; Shimodaira, H. Pvclust: An R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1540–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J.; Petty, N.K.; Beatson, S.A. Easyfig: A genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1009–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Raphenya, A.R.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Tsang, K.K.; Bouchard, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Huynh, W.; Nguyen, A.-L.V.; Cheng, A.A.; Liu, S.; et al. CARD 2020: Antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, D517–D525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, J.; Yu, J.; Yao, Z.; Sun, L.; Shen, Y.; Jin, Q. VFDB: A reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, D325–D328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larralde, M.; Zeller, G. PyHMMER: A Python library binding to HMMER for efficient sequence analysis. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.T.; Paquet, V.E.; Bernatchez, A.; Tremblay, D.M.; Moineau, S.; Charette, S.J. Characterization and diversity of phages infecting Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquet, V.E.; Vincent, A.T.; Moineau, S.; Charette, S.J. Beyond the A-layer: Adsorption of lipopolysaccharides and characterization of bacteriophage-insensitive mutants of Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplessis, M.; Moineau, S. Identification of a genetic determinant responsible for host specificity in Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophages. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 41, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.H. Adsorption of phages. In Bacteriophages; Interscience Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 3.5.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2018. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Linares, R.; Arnaud, C.-A.; Degroux, S.; Schoehn, G.; Breyton, C. Structure, function and assembly of the long, flexible tail of siphophages. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2020, 45, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, J.M.; Dunstan, R.A.; Lithgow, T.; Coulibaly, F. Tall tails: Cryo-electron microscopy of phage tail DNA ejection conduits. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2022, 50, 459-22W. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Nayak, A.; Sharma, R.; Singh, A.; Singh, R.; Tiwari, S. Isolation and identification of novel Staphylococcus phage as a novel therapeutic agent from sewage of livestock farms. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2025, 59, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, A.M. Prevalence and Characterization of Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteriophages Isolated from Swine Farms Across the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2020. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/192716 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Wen, H.; Yuan, L.; Ye, J.-H.; Li, Y.-J.; Yang, Z.-Q.; Zhou, W.-Y. Isolation and characterization of a broad-spectrum phage SapYZU11 and its potential application for biological control of Staphylococcus aureus. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2023, 15, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuk, Y.; Kukhtyn, M.; Kernychnyi, S.; Laiter-Moskaliuk, S.; Prosyanyi, S.; Boltyk, N. Sensitivity of Staphylococcus aureus cultures of different biological origin to commercial bacteriophages and phages of Staphylococcus aureus var. bovis. Vet. World 2021, 14, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.J.; Chandra, M.; Kaur, G.; Narang, D. Isolation and characterization of lytic bacteriophages against Staphylococcus aureus. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2025, 56, 3059–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, I.A.; Asif, M.; Tabassum, R.; Abbas, Z.; ur Rehman, S. Storage of bacteriophages at 4 C leads to no loss in their titer after one year. Pak. J. Zool. 2018, 50, 2395–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Menendez, E.; Fernandez, L.; Gutierrez, D.; Rodriguez, A.; Martinez, B.; Garcia, P. Comparative analysis of different preservation techniques for the storage of Staphylococcus phages aimed for the industrial development of phage-based antimicrobial products. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, R.; Mugabi, R.; Hetesy, G.; Fox, L.; De Vliegher, S.; De Visscher, A.; Barlow, J.W.; Sensabaugh, G. Characterization of genetic diversity and population structure within Staphylococcus chromogenes by multilocus sequence typing. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0243688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simojoki, H.; Orro, T.; Taponen, S.; Pyörälä, S. Host response in bovine mastitis experimentally induced with Staphylococcus chromogenes. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 134, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochniarz, M.; Dzięgiel, B.; Nowaczek, A.; Wawron, W.; Dąbrowski, R.; Szczubiał, M.; Winiarczyk, S. Factors responsible for subclinical mastitis in cows caused by Staphylococcus chromogenes and its susceptibility to antibiotics based on bap, fnbA, eno, mecA, tetK, and ermA genes. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 9514–9520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseem, M.N.; Turni, C.; Gilbert, R.; Raza, A.; Allavena, R.; McGowan, M.; Constantinoiu, C.; Ong, C.T.; Tabor, A.E.; James, P. Role of Staphylococcus agnetis and Staphylococcus hyicus in the pathogenesis of buffalo fly skin lesions in cattle. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00873-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, R.P.; Muthukrishnan, G.; Castoe, T.A.; Tafur, S.; Cole, A.M.; Parkinson, C.L. Phylogenetic relationships among Staphylococcus species and refinement of cluster groups based on multilocus data. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebremedhin, B.; Layer, F.; Konig, W.; Konig, B. Genetic classification and distinguishing of Staphylococcus species based on different partial gap, 16S rRNA, hsp60, rpoB, sodA, and tuf gene sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, M.; Shintani, M. Microbial evolution through horizontal gene transfer by mobile genetic elements. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, G.; Ahn, J. Evaluation of phage adsorption to Salmonella typhimurium exposed to different levels of pH and antibiotic. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 150, 104726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Smet, J.; Hendrix, H.; Blasdel, B.G.; Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Lavigne, R. Pseudomonas predators: Understanding and exploiting phage–host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldovan, R.; Chapman-McQuiston, E.; Wu, X. On kinetics of phage adsorption. Biophys. J. 2007, 93, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcutt, M.J.; Foecking, M.F.; Hsieh, H.-Y.; Adkins, P.R.F.; Stewart, G.C.; Middleton, J.R. Sequence analysis of Staphylococcus hyicus ATCC 11249T, an etiological agent of exudative epidermitis in swine, reveals a type VII secretion system locus and a novel 116-kilobase genomic island harboring toxin-encoding genes. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e01525-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt, K.; LeBel, G.; Yi, L.; Grenier, D. In vitro antibacterial activity of plant essential oils against Staphylococcus hyicus and Staphylococcus aureus, the causative agents of exudative epidermitis in pigs. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, S.; Labrie, J.; Jacques, M. The Mastitis Pathogens Culture Collection. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phage | Source | First Amplification | Second Amplification | Titer (PFU/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Lysis | Solid Lysis | Liquid Lysis | Solid Lysis | |||

| STAE-4 | Water | − | + | + | + | 1 × 108 |

| STAF-3 | Manure from pit | − | + | + | + | 3 × 109 |

| STAM-1 | Feed + water | − | + | + | + | 3 × 109 |

| Phage | Capsid Diameter (nm) | Tail Length (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| STAE-4 | 76.8 ± 2.3 | 355.6 ± 7.4 |

| STAF-3 | 74.5 ± 2.5 | 330.4 ± 34.8 |

| STAM-1 | 75.5 ± 5.6 | 338.9 ± 17.8 |

| Strain ID | Number of Strains | Phage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAE-4 | STAF-3 | STAM-1 | ||

| S. hyicus | 49 | |||

| SC304, SC305, SC309, SC358, SC361, SC363, SC369, SC370, SC371, SC372, SC375, SC378, SC381 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SC306, SC359, SC364 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 |

| SC367, SC388, SC393 | 3 | 0 | 0.001 | 0 |

| SC307, SC389 | 2 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.001 |

| SC386 | 1 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| SC392 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0 |

| SC299, SC300, SC302, SC303, SC308, SC310, SC311, SC357, SC362, SC365, SC373, SC374, SC376, SC377, SC379, SC380, SC383, SC384, SC387, SC390, SC391, SC394 | 21 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| SC368 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.001 |

| SC360 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| SC382 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| SC366 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| S. agnetis | 17 | |||

| SC342, SC347 | 2 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| SC341, SC343, SC344, SC345, SC346, SC348, SC349, SC350, SC351, SC352, SC353, SC354, SC356 | 13 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| SC355 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.01 |

| SC298 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.5 |

| S. chromogenes | 14 | |||

| SC436, SC428, SC431, SC435 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SC426, SC429, SC430, SC433, SC434 | 5 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| SC432 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.5 | 1 |

| SC427 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| SC438 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| SC437, SC385 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chhanda, M.S.; St-Laurent, R.E.; Paquet, V.E.; Deslauriers, N.; Gagné-Thivierge, C.; Denicourt, M.; Lambert, M.-È.; Vincent, A.T.; Charette, S.J. Three Staphylococcus Bacteriophages Isolated from Swine Farm Environment in Quebec, Canada, Infecting S. chromogenes. Viruses 2026, 18, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010146

Chhanda MS, St-Laurent RE, Paquet VE, Deslauriers N, Gagné-Thivierge C, Denicourt M, Lambert M-È, Vincent AT, Charette SJ. Three Staphylococcus Bacteriophages Isolated from Swine Farm Environment in Quebec, Canada, Infecting S. chromogenes. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010146

Chicago/Turabian StyleChhanda, Mousumi Sarker, Rébecca E. St-Laurent, Valérie E. Paquet, Nicolas Deslauriers, Cynthia Gagné-Thivierge, Martine Denicourt, Marie-Ève Lambert, Antony T. Vincent, and Steve J. Charette. 2026. "Three Staphylococcus Bacteriophages Isolated from Swine Farm Environment in Quebec, Canada, Infecting S. chromogenes" Viruses 18, no. 1: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010146

APA StyleChhanda, M. S., St-Laurent, R. E., Paquet, V. E., Deslauriers, N., Gagné-Thivierge, C., Denicourt, M., Lambert, M.-È., Vincent, A. T., & Charette, S. J. (2026). Three Staphylococcus Bacteriophages Isolated from Swine Farm Environment in Quebec, Canada, Infecting S. chromogenes. Viruses, 18(1), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010146