Genetic Diversity of Vif and Vpr Accessory Proteins in HIV-1 Group M Clades

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequence Dataset Compilation

2.2. Consensus Sequence Calculation

2.3. Amino Acid Frequencies and Diversity

2.4. Structural Analysis and Modeling

2.5. Calculation of the Variability Index

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

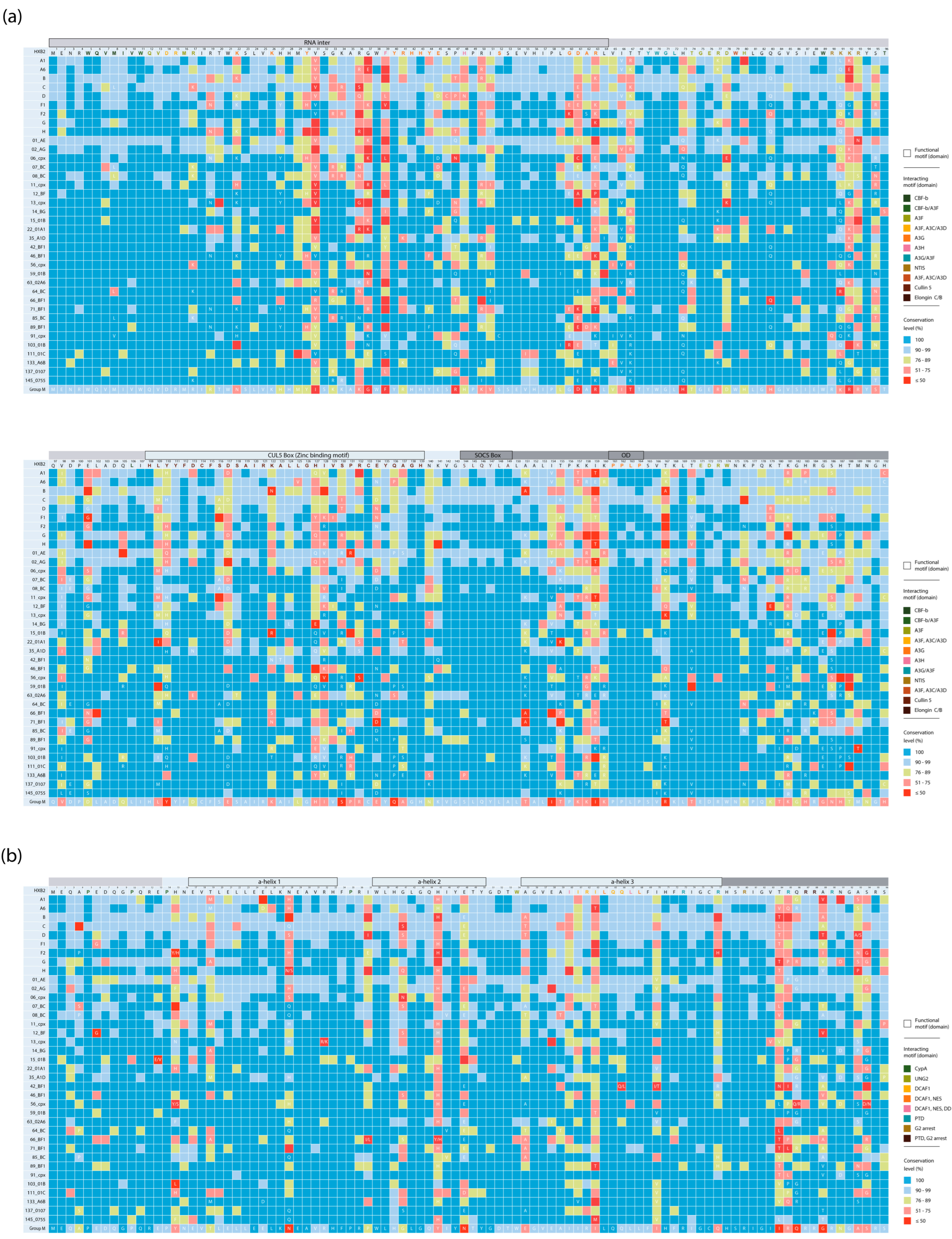

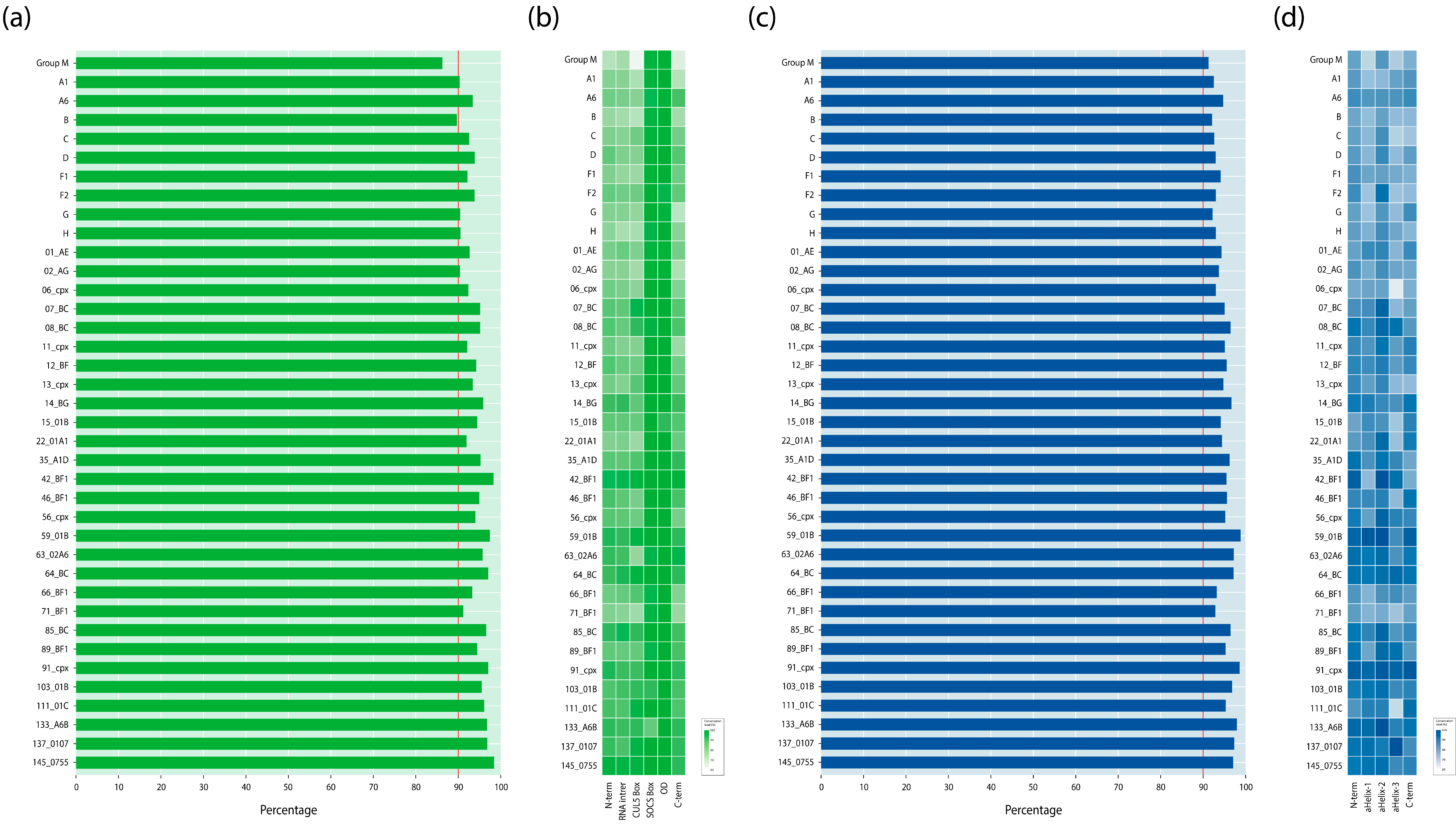

3.1. Amino Acid Residue Variability in HIV-1 Group M Clades

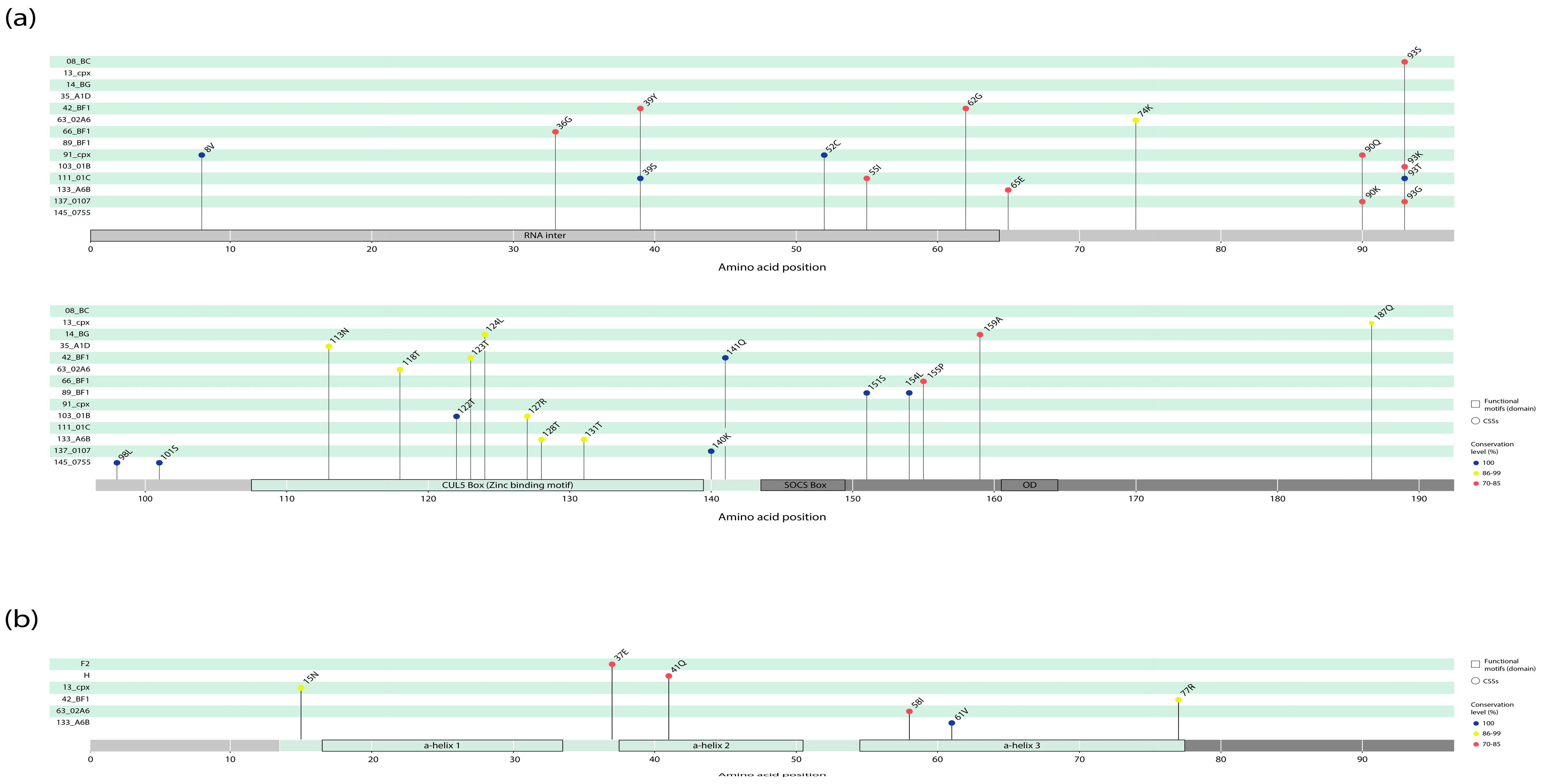

3.2. Changes in HIV-1 Consensus Sequences

3.3. Clade-Specific Amino Acid Residue Substitutions in the Vif and Vpr Proteins of HIV-1 Group M

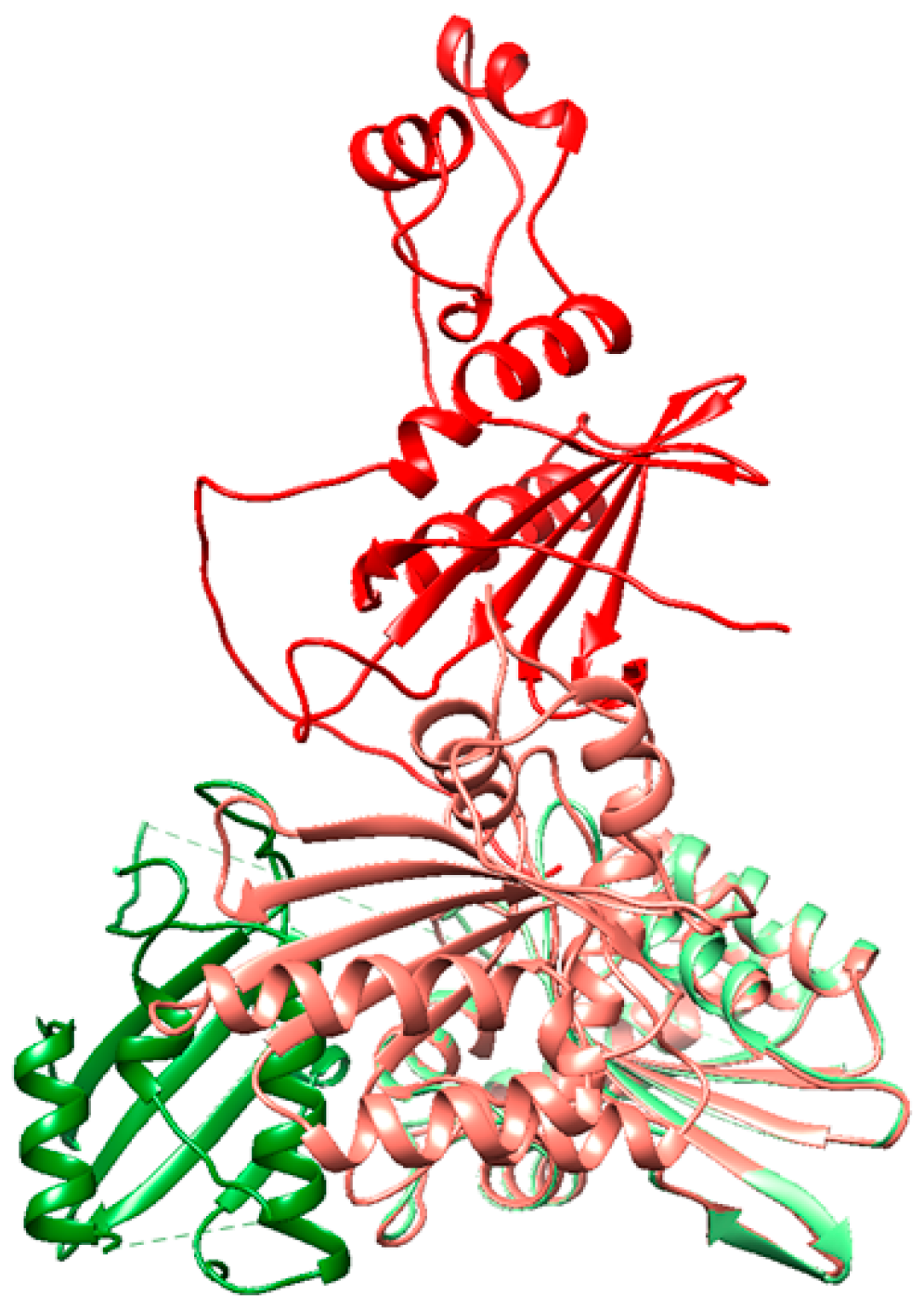

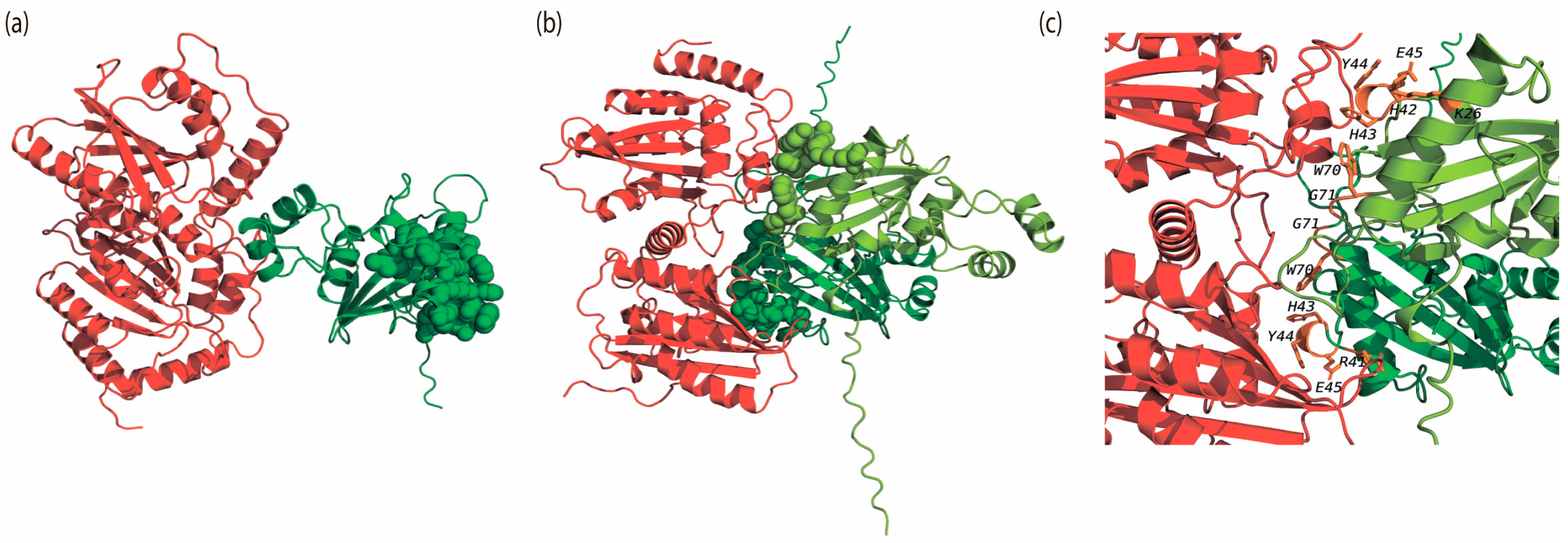

3.4. Spatial Alignment of the Monomeric and Oligomeric Structures of Vif and Vpr Modeling of Vif-APOBEC3G and UNG-Vpr Interactions

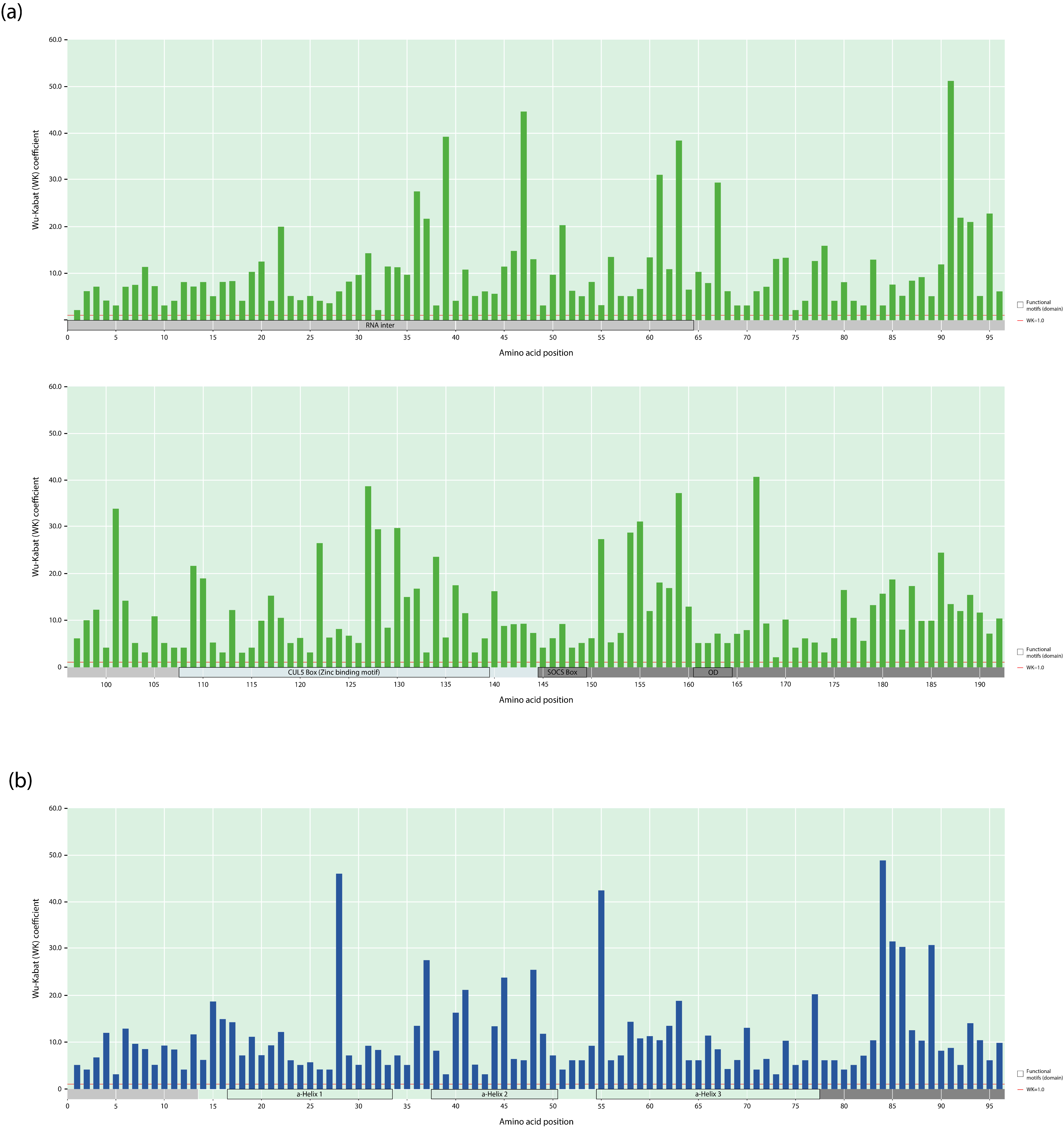

3.5. Wu–Kabat Protein Variability Index of the Vif and Vpr Proteins in the HIV-1 Group M

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nair, M.; Gettins, L.; Fuller, M.; Kirtley, S.; Hemelaar, J. Global and Regional Genetic Diversity of HIV-1 in 2010–21: Systematic Review and Analysis of Prevalence. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bbosa, N.; Kaleebu, P.; Ssemwanga, D. HIV Subtype Diversity Worldwide. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2019, 14, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Désiré, N.; Cerutti, L.; Le Hingrat, Q.; Perrier, M.; Emler, S.; Calvez, V.; Descamps, D.; Marcelin, A.-G.; Hué, S.; Visseaux, B. Characterization Update of HIV-1 M Subtypes Diversity and Proposal for Subtypes A and D Sub-Subtypes Reclassification. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, J.; Vallari, A.; McArthur, C.; Sthreshley, L.; Cloherty, G.A.; Berg, M.G.; Rodgers, M.A. Brief Report: Complete Genome Sequence of CG 0018a-01 Establishes HIV-1 Subtype L. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2020, 83, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes Da Silva, R.K.; Monteiro de Pina Araujo, I.I.; Venegas Maciera, K.; Gonçalves Morgado, M.; Lindenmeyer Guimarães, M. Genetic Characterization of a New HIV-1 Sub-Subtype A in Cabo Verde, Denominated A8. Viruses 2021, 13, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halikov, M.R.; Ekushov, V.E.; Totmenin, A.V.; Gashnikova, N.M.; Antonets, M.E.; Tregubchak, T.V.; Skliar, L.P.; Solovyova, N.P.; Gorelova, I.S.; Beniova, S.N. Identification of a Novel HIV-1 Circulating Recombinant Form CRF157_A6C in Primorsky Territory, Russia. J. Infect. 2024, 88, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ma, Y.; Chen, H.; Dai, J.; Dong, L.; Jia, M. Identification of a Complex Second-Generation HIV-1 Circulating Recombinant Form (CRF158_0107) among Men Who Have Sex with Men in China. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pant Pai, N.; Shivkumar, S.; Cajas, J.M. Does Genetic Diversity of HIV-1 Non-B Subtypes Differentially Impact Disease Progression in Treatment-Naive HIV-1-Infected Individuals? A Systematic Review of Evidence: 1996–2010. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2012, 59, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltzfus, C.M. Regulation of HIV-1 Alternative RNA Splicing and Its Role in Virus Replication. Adv. Virus Res. 2009, 74, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stupfler, B.; Verriez, C.; Gallois-Montbrun, S.; Marquet, R.; Paillart, J.C. Degradation-Independent Inhibition of APOBEC3G by the HIV-1 Vif Protein. Viruses 2021, 13, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.M.; Marin, M.; Kozak, S.L.; Kabat, D. The Viral Infectivity Factor (Vif) of HIV-1 Unveiled. Trends Mol. Med. 2004, 10, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedler, A.; Zakai, N.; Karni, O.; Friedler, D.; Gilon, C.; Loyter, A. Identification of a Nuclear Transport Inhibitory Signal (NTIS) in the Basic Domain of HIV-1 Vif Protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 289, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, F.C.; Lee, J.E. Structural Perspectives on HIV-1 Vif and APOBEC3 Restriction Factor Interactions. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriet, S.; Mercenne, G.; Bernacchi, S.; Paillart, J.C.; Marquet, R. Tumultuous Relationship between the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Viral Infectivity Factor (Vif) and the Human APOBEC-3G and APOBEC-3F Restriction Factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009, 73, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pomerantz, R.J.; Dornadula, G.; Sun, Y. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Vif Protein Is an Integral Component of an mRNP Complex of Viral RNA and Could Be Involved in the Viral RNA Folding and Packaging Process. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 8252–8261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batisse, J.; Guerrero, S.; Bernacchi, S.; Sleiman, D.; Gabus, C.; Darlix, J.L.; Marquet, R.; Tisné, C.; Paillart, J.C. The Role of Vif Oligomerization and RNA Chaperone Activity in HIV-1 Replication. Virus Res. 2012, 169, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H. The Multimerization of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type I Vif Protein: A Requirement for Vif Function in the Viral Life Cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 4889–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacchi, S.; Mercenne, G.; Tournaire, C.; Marquet, R.; Paillart, J.C. Importance of the Proline-Rich Multimerization Domain on the Oligomerization and Nucleic Acid Binding Properties of HIV-1 Vif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 2404–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, M.; Rappaport, J. HIV-1 Accessory Protein Vpr: Relevance in the Pathogenesis of HIV and Potential for Therapeutic Intervention. Retrovirology 2011, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodder, S.B.; Gummuluru, S. Illuminating the Role of Vpr in HIV Infection of Myeloid Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas-Torres, C.A.; Schindler, M. HIV-1 Vpr Functions in Primary CD4+ T Cells. Viruses 2024, 16, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Chiang, S.F.; Lin, T.Y.; Chiou, S.H.; Chow, K.C. HIV-1 Vpr Triggers Mitochondrial Destruction by Impairing Mfn2-Mediated ER-Mitochondria Interaction. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.E. The HIV-1 Vpr Protein: A Multifaceted Target for Therapeutic Intervention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabryova, H.; Strebel, K. Vpr and Its Cellular Interaction Partners: Are We There Yet? Cells 2019, 8, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kara, H.; Chazal, N.; Bouaziz, S. Is Uracil-DNA Glycosylase UNG2 a New Cellular Weapon Against HIV-1? Curr. HIV Res. 2019, 17, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Makar, T.; Gerzanich, V.; Kalakonda, S.; Ivanova, S.; Pereira, E.F.R.; Andharvarapu, S.; Zhang, J.; Simard, J.M.; Zhao, R.Y. HIV-1 Vpr-Induced Proinflammatory Response and Apoptosis Are Mediated through the Sur1-Trpm4 Channel in Astrocytes. mBio 2020, 11, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukerjee, R.; Chang, J.R.; Del Valle, L.; Bagashev, A.; Gayed, M.M.; Lyde, R.B.; Hawkins, B.J.; Brailoiu, E.; Cohen, E.; Power, C.; et al. Deregulation of MicroRNAs by HIV-1 Vpr Protein Leads to the Development of Neurocognitive Disorders. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 34976–34985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morellet, N.; Bouaziz, S.; Petitjean, P.; Roques, B.P. NMR Structure of the HIV-1 Regulatory Protein VPR. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 327, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, J.V.; Dujardin, D.; Godet, J.; Didier, P.; De Mey, J.; Darlix, J.L.; Mély, Y.; de Rocquigny, H. HIV-1 Vpr Oligomerization but Not That of Gag Directs the Interaction between Vpr and Gag. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwabu, Y.; Kinomoto, M.; Tatsumi, M.; Fujita, H.; Shimura, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Ishizaka, Y.; Nolan, D.; Mallal, S.; Sata, T.; et al. Differential Anti-APOBEC3G Activity of HIV-1 Vif Proteins Derived from Different Subtypes. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 35350–35358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsard, L.; Raja, R.; Panwar, V.; Saini, S.; Mohankumar, K.; Sridharan, S.; Padmapriya, R.; Chaudhuri, S.; Ramachandran, V.G.; Banerjea, A.C. Genetic and Functional Characterization of HIV-1 Vif on APOBEC3G Degradation: First Report of Emergence of B/C Recombinants from North India. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colle, J.-H.; Rose, T.; Rouzioux, C.; Garcia, A. Two Highly Variable Vpr84 and Vpr85 Residues within the HIV-1-Vpr C-Terminal Protein Transduction Domain Control Transductionnal Activity and Define a Clade Specific Polymorphism. World J. AIDS 2014, 4, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, K.; Walker, L.A.; Guha, D.; Murali, R.; Watkins, S.C.; Tarwater, P.; Srinivasan, A.; Ayyavoo, V. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Vpr Polymorphisms Associated with Progressor and Nonprogressor Individuals Alter Vpr-Associated Functions. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, V.; Zennou, V.; Murray, D.; Huang, Y.; Ho, D.D.; Bieniasz, P.D. Natural Variation in Vif: Differential Impact on APOBEC3G/3F and a Potential Role in HIV-1 Diversification. PLoS Pathog. 2005, 1, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dampier, W.; Antell, G.C.; Aiamkitsumrit, B.; Nonnemacher, M.R.; Jacobson, J.M.; Pirrone, V.; Zhong, W.; Kercher, K.; Passic, S.; Williams, J.W.; et al. Specific Amino Acids in HIV-1 Vpr Are Significantly Associated with Differences in Patient Neurocognitive Status. J. Neurovirol. 2017, 23, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizinoto, M.C.; Yabe, S.; Leal, É.; Kishino, H.; de Oliveira Martins, L.; de Lima, M.L.; Morais, E.R.; Diaz, R.S.; Janini, L.M. Codon Pairs of the HIV-1 Vif Gene Correlate with CD4+ T Cell Count. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Wang, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, N.; Meng, L.; Gai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Yu, B.; et al. A Novel HIV-1 Inhibitor That Blocks Viral Replication and Rescues APOBEC3s by Interrupting Vif/CBFβ Interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 14592–14605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Seyedinkhorasani, M.; Bolhassani, A. Conserved Multiepitope Vaccine Constructs: A Potent HIV-1 Therapeutic Vaccine in Clinical Trials. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 27, 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, K.; Ishii, H.; Murakami, T.; Takeshima, S.-n.; Chutiwitoonchai, N.; Kodama, E.N.; Kawaji, K.; Kondoh, Y.; Honda, K.; Osada, H.; et al. Synthesis of a Vpr-Binding Derivative for Use as a Novel HIV-1 Inhibitor. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, A.; Baesi, K.; Agi, E.; Marouf, G.; Ahmadi, M.; Bolhassani, A. HIV-1 Accessory Proteins: Which One Is Potentially Effective in Diagnosis and Vaccine Development? Protein Pept. Lett. 2021, 28, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewitus, E.; Li, Y.; Rolland, M. HIV-1 Vif Global Diversity and Possible APOBEC-Mediated Response since 1980. Virus Evol. 2024, 11, veae108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.E. HIV-1 Vif protein sequence variations in South African people living with HIV and their influence on Vif-APOBEC3G interaction. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 43, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, B.; Glashoff, R.; Engelbrecht, S. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis of HIV type 1 vpr sequences of South African strains. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2009, 25, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanova, F.; Barreiros, M.; Janini, L.M.; Diaz, R.S.; Leal, É. Genetic Diversity of HIV-1 Gene vif Among Treatment-Naive Brazilians. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2017, 33, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhachev, I.V.; Balabaev, N.K.; Galzitskaya, O.V. Available Instruments for Analyzing Molecular Dynamics Trajectories. Open Biochem. J. 2016, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likhachev, I.V.; Balabaev, N.K. Parallelism of different levels in the program of molecular dynamics simulation PUMA-CUDA. In Proceedings of the International Conference “Mathematical Biology and Bioinformatics”, Pushchino, Russia, 14–19 October 2018; Lakhno, V.D., Ed.; Paper No. e44; IMPB RAS: Pushchino, Russia, 2018; Volume 7, (In Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat, E.A.; Wu, T.T.; Bilofsky, H. Unusual distributions of amino acids in complementarity-determining (hypervariable) segments of heavy and light chains of immunoglobulins and their possible roles in specificity of antibody-combining sites. J. Biol. Chem. 1977, 252, 6609–6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaori-Kondo, A.; Shindo, K. HIV-1 Vif: A guardian of the virus that opens up a new era in the research field of restriction factors. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenzel, C.A.; Hérate, C.; Benichou, S. HIV-1 Vpr-a still “enigmatic multitasker”. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüler, W.; Wecker, K.; de Rocquigny, H.; Baudat, Y.; Sire, J.; Roques, B.P. NMR structure of the (52–96) C-terminal domain of the HIV-1 regulatory protein Vpr: Molecular insights into its biological functions. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 285, 2105–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D.L.; Lenardo, M.J. Vpr Cytopathicity Independent of G2/M Cell Cycle Arrest in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1-Infected CD4+ T Cells. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 8878–8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Palomares, S.E.; Hernandez-Sanchez, P.G.; Esparza-Perez, M.A.; Arguello, J.R.; Noyola, D.E.; Garcia-Sepulveda, C.A. Molecular Characterization of Mexican HIV-1 Vif Sequences. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016, 32, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossenkhan, R.; Novitsky, V.; Sebunya, T.K.; Musonda, R.; Gashe, B.A.; Essex, M. Viral Diversity and Diversification of Major Non-Structural Genes vif, vpr, vpu, tat exon 1 and rev exon 1 during Primary HIV-1 Subtype C Infection. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Gupta, P.; Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y. Molecular characterization of the HIV type 1 vpr gene in infected Chinese former blood/plasma donors at different stages of diseases. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2008, 24, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonova, A.A.; Lebedev, A.V.; Ozhmegova, E.N.; Shlykova, A.V.; Lapavok, I.A.; Kuznetsova, A.I. Variability of non-structural proteins of HIV-1 sub-subtype A6 (Retroviridae: Orthoretrovirinae: Lentivirus: Human immunodeficiency virus-1, sub-subtype A6) variants circulating in different regions of the Russian Federation. Vopr Virusol. 2024, 69, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A.I.; Antonova, A.A.; Makeeva, E.A.; Kim, K.V.; Munchak, I.M.; Mezhenskaya, E.N.; Orlova-Morozova, E.A.; Pronin, A.Y.; Prilipov, A.G.; Galzitskaya, O.V. Vpr, accessory protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (Retroviridae: Orthoretrovirinae: Lentivirus: Human immunodeficiency virus-1): Features of genetic variants of the virus circulating in the Moscow region in 2019-2020. Vopr Virusol. 2025, 70, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, A.; Kim, K.; Ozhmegova, E.; Antonova, A.; Kazennova, E.; Tumanov, A.; Kuznetsova, A. Rev Protein Diversity in HIV-1 Group M Clades. Viruses 2024, 16, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penn, O.; Stern, A.; Rubinstein, N.D.; Dutheil, J.; Bacharach, E.; Galtier, N.; Pupko, T. Evolutionary modeling of rate shifts reveals specificity determinants in HIV-1 subtypes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Klundert, M.A.A.; Antonova, A.; Di Teodoro, G.; Ceña Diez, R.; Chkhartishvili, N.; Heger, E.; Kuznetsova, A.; Lebedev, A.; Narayanan, A.; Ozhmegova, E.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of HIV-1 in Eastern Europe and Russia. Viruses 2022, 14, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyano-Hernáez, P.; Reinosa, R.; Holguín, A. Genetic Diversity and Low Therapeutic Impact of Variant-Specific Markers in HIV-1 Pol Proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 866705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyano-Hernáez, P.; Reinosa, R.; Holguín, Á. HIV Capsid Protein Genetic Diversity Across HIV-1 Variants and Impact on New Capsid-Inhibitor Lenacapavir. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 854974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehle, A.; Thomas, E.R.; Rajendran, K.S.; Gabuzda, D. A zinc-binding region in Vif binds Cul5 and determines cullin selection. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 17259–17265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnitz, R.A.; Chaigne-Delalande, B.; Bolton, D.L.; Lenardo, M.J. Exposed Hydrophobic Residues in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Vpr Helix-1 Are Important for Cell Cycle Arrest and Cell Death. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezov, T.T.; Korovkin, B.F. Biological Chemistry; Medicine: Moscow, Russia, 1998. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lobanov, M.Y.; Pereyaslavets, L.B.; Likhachev, I.V.; Matkarimov, B.T.; Galzitskaya, O.V. Is there an advantageous arrangement of aromatic residues in proteins? Statistical analysis of aromatic interactions in globular proteins. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 5960–5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maio, F.A.; Rocco, C.A.; Aulicino, P.C.; Bologna, R.; Mangano, A.; Sen, L. Effect of HIV-1 Vif variability on progression to pediatric AIDS and its association with APOBEC3G and CUL5 polymorphisms. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011, 11, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clade a | Number of Near Full-Length HIV-1 Genomes in the HIV Database | Number of Downloaded HIV-1 Sequences Used in Consensus | Number of Changes (Vif|Vpr) | Mean Changes per Sequence (Vif|Vpr) c | Variable Positions (Vif|Vpr) (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insertions b | Deletions | Substitutions | |||||

| A1 | 813 | 250 | 2|49 | 13|21 | 4595|1755 | 18.4|7.1 | 75.0|72.9 |

| A6 | 235 | 221 | 0|6 | 3|21 | 2753|1075 | 12.5|5.0 | 67.7|60.4 |

| B | 11,407 | 1888 | 86|135 | 137|306 | 36,917|13,881 | 19.6|7.5 | 94.3|97.9 |

| C | 2449 | 878 | 19|10 | 29|51 | 12,377|6083 | 14.1|7.0 | 92.2|97.9 |

| D | 225 | 160 | 4|0 | 3|5 | 1855|1072 | 11.6|6.7 | 62.0|70.8 |

| F1 | 79 | 73 | 7|2 | 2|4 | 1086|404 | 14.9|5.6 | 52.6|46.8 |

| F2 | 14 | 14 | 1|0 | 0|0 | 163|93 | 11.6|6.6 | 30.0|26.0 |

| G | 101 | 89 | 5|13 | 140|7 | 1603|652 | 19.6|7.4 | 64.6|58.3 |

| H | 10 | 10 | 1|0 | 0|1 | 180|65 | 18.0|6.6 | 36.5|28.1 |

| 01_AE | 2275 | 613 | 8|43 | 132|106 | 8373|3206 | 13.9|5.4 | 84.4|84.4 |

| 02_AG | 233 | 205 | 8|0 | 17|5 | 3725|1198 | 18.3|5.9 | 76.0|69.8 |

| 06_cpx | 19 | 17 | 0|0 | 2|0 | 243|112 | 14.4|6.6 | 37.0|40.6 |

| 07_BC | 48 | 43 | 0|1 | 5|1 | 390|200 | 9.2|4.7 | 39.4|41.7 |

| 08_BC | 37 | 33 | 0|0 (*) | 7|1 | 297|111 | 9.2|3.4 | 48.2|44.8 |

| 11_cpx | 25 | 24 | 3|0 | 2|3 | 357|107 | 15.0|4.6 | 43.2|30.2 |

| 12_BF | 14 | 14 | 1|0 | 0|0 | 158|65 | 11.3|4.6 | 32.8|32.3 |

| 13_cpx | 10 | 10 | 5|0 | 1|2 | 124|47 | 12.5|4.9 | 27.6|22.9 |

| 14_BG | 14 | 12 | 0|0 | 0|0 | 93|37 | 7.8|3.1 | 20.8|15.6 |

| 15_01B | 8 | 8 | 0|7 | 0|1 | 87|43 | 10.9|5.5 | 22.9|27.1 |

| 22_01A1 | 21 | 15 | 0|0 | 1|1 | 228|77 | 15.3|5.2 | 35.9|30.2 |

| 35_A1D | 22 | 22 | 0|0 | 0|0 | 198|79 | 9.0|3.6 | 38.0|28.1 |

| 42_BF1 | 17 | 15 | 0|0 | 0|0 | 53|80 | 3.5|5.3 | 9.4|10.4 |

| 46_BF1 | 8 | 8 | 0|0 | 0|0 | 76|36 | 9.5|4.5 | 23.4|21.9 |

| 56_cpx | 8 | 8 | 0|0 | 0|0 | 91|40 | 11.4|5.0 | 27.1|19.8 |

| 59_01B | 9 | 8 | 0|0 | 0|0 | 38|9 | 4.8|1.1 | 9.9|5.2 |

| 63_02A6 | 23 | 22 | 0|15 | 0|0 | 177|56 | 8.0|2.5 | 27.1|22.9 |

| 64_BC | 9 | 8 | 0|0 (*) | 0|0 | 48|21 | 6.0|2.6 | 14.0|16.7 |

| 66_BF1 | 8 | 8 | 0|2 | 0|2 | 102|52 | 12.8|6.8 | 24.5|25.0 |

| 71_BF1 | 14 | 13 | 0|0 | 0|0 | 218|87 | 16.8|6.7 | 38.0|34.4 |

| 85_BC | 11 | 11 | 0|0 (*) | 1|0 | 71|36 | 6.5|3.3 | 20.7|21.9 |

| 89_BF1 | 9 | 9 | 2|0 | 0|0 | 95|42 | 10.6|4.7 | 23.4|21.9 |

| 91_cpx | 10 | 10 | 0|0 | 0|2 | 55|10 | 5.5|1.2 | 13.5|6.25 |

| 103_01B | 10 | 10 | 0|0 | 0|0 | 85|29 | 8.5|2.9 | 19.8|13.5 |

| 111_01C | 8 | 8 | 0|0 | 0|0 | 58|35 | 7.3|4.4 | 19.3|19.8 |

| 133_A6B | 8 | 8 | 0|0 | 0|1 | 48|14 | 6.0|1.9 | 16.7|9.4 |

| 137_0107 | 9 | 9 | 0|0 (*) | 0|0 | 53|21 | 5.9|2.3 | 17.1|14.6 |

| 145_0755 | 10 | 10 | 0|0 (*) | 0|0 | 28|27 | 2.8|2.7 | 7.8|14.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Galzitskaya, O.; Lebedev, A.; Antonova, A.; Mezhenskaya, E.; Glyakina, A.; Deryusheva, E.; Likhachev, I.; Kuznetsova, A. Genetic Diversity of Vif and Vpr Accessory Proteins in HIV-1 Group M Clades. Viruses 2026, 18, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010116

Galzitskaya O, Lebedev A, Antonova A, Mezhenskaya E, Glyakina A, Deryusheva E, Likhachev I, Kuznetsova A. Genetic Diversity of Vif and Vpr Accessory Proteins in HIV-1 Group M Clades. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalzitskaya, Oxana, Aleksey Lebedev, Anastasiia Antonova, Ekaterina Mezhenskaya, Anna Glyakina, Evgeniya Deryusheva, Ilya Likhachev, and Anna Kuznetsova. 2026. "Genetic Diversity of Vif and Vpr Accessory Proteins in HIV-1 Group M Clades" Viruses 18, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010116

APA StyleGalzitskaya, O., Lebedev, A., Antonova, A., Mezhenskaya, E., Glyakina, A., Deryusheva, E., Likhachev, I., & Kuznetsova, A. (2026). Genetic Diversity of Vif and Vpr Accessory Proteins in HIV-1 Group M Clades. Viruses, 18(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010116