Rheumatological Manifestations in People Living with Human T-Lymphotropic Viruses 1 and 2 (HTLV-1 and HTLV-2) in Northern Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Ethical Considerations

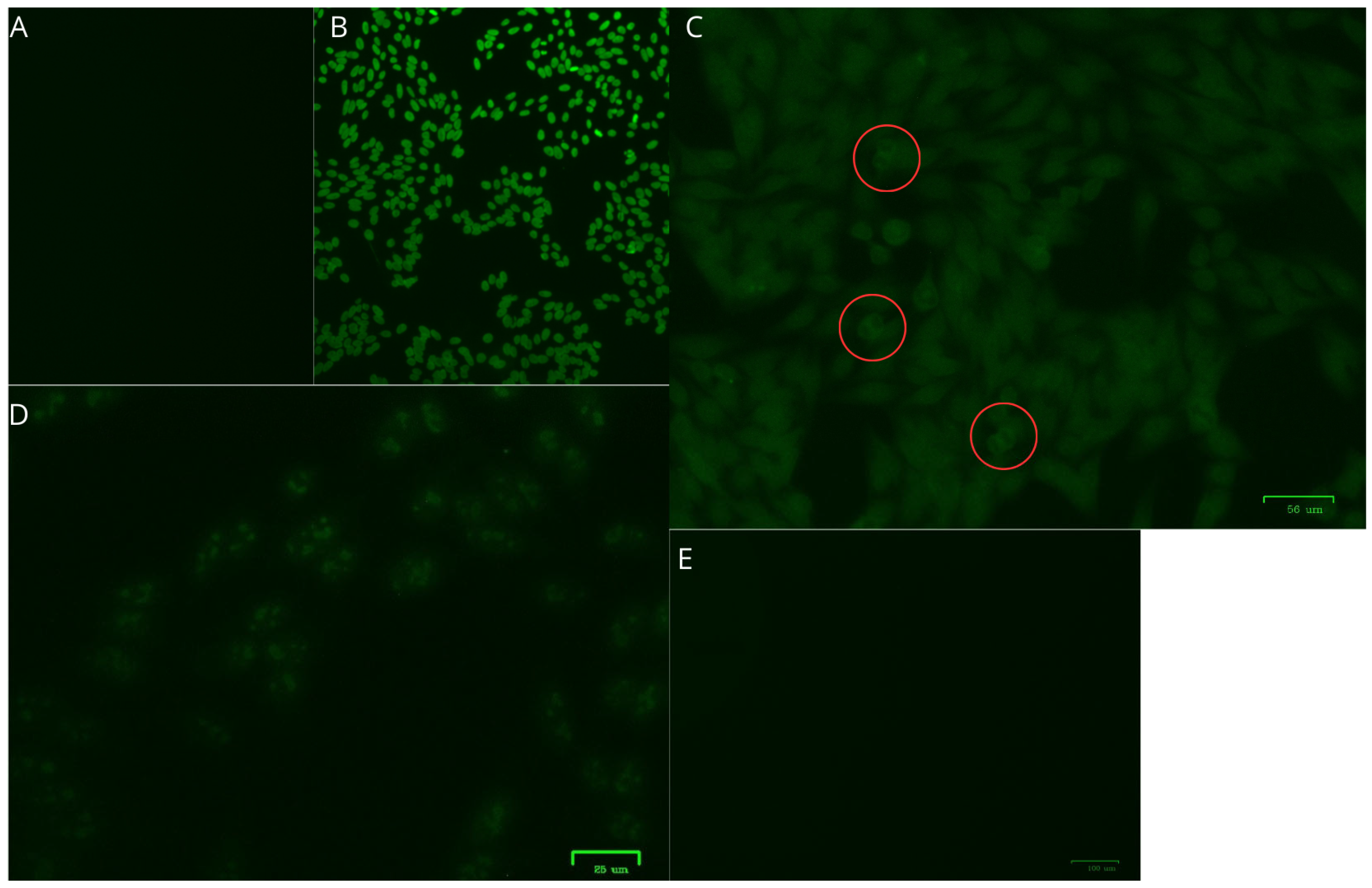

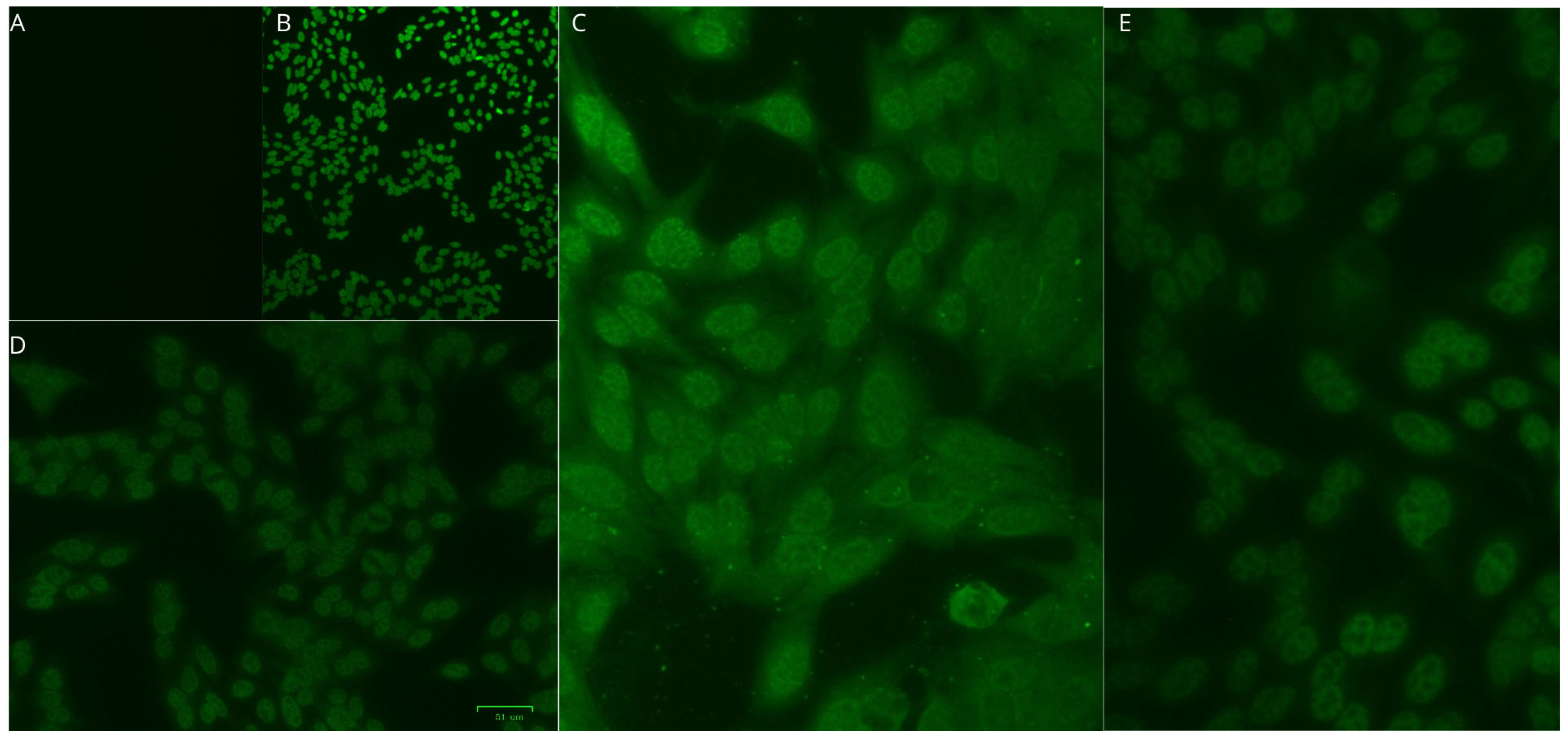

2.3. HTLV Diagnosis

2.4. Clinical Analysis

2.5. Autoantibody Testing

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ICTV—International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Taxonomy History: Primate T-Lymphotropic Virus 1. 2025. Available online: https://ictv.global/report/chapter/retroviridae/retroviridae/deltaretrovirus (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Martinez, M.P.; Al-Saleem, J.; Green, P.L. Comparative virology of HTLV-1 and HTLV-2. Retrovirology 2019, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poiesz, B.J.; Ruscetti, F.W.; Reitz, M.S.; Kalyanaraman, V.S.; Gallo, R.C. Isolation of a new type C retrovirus (HTLV) in primary uncultured cells of a patient with Sézary T-cell leukaemia. Nature 1981, 294, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyanaraman, V.S.; Sarngadharan, M.G.; Robert-Guroff, M.; Miyoshi, I.; Golde, D.; Gallo, R.C. A new subtype of human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV-II) associated with a T-cell variant of hairy cell leukemia. Science 1982, 218, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, N.D.; Heneine, W.; Carr, J.K.; Garcia, A.D.; Shanmugam, V.; Tamoufe, U.; Torimiro, J.N.; Prosser, A.T.; Lebreton, M.; Mpoudi-Ngole, E.; et al. Emergence of unique primate T-lymphotropic viruses among central African bushmeat hunters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7994–7999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, Y.T.; Jia, H.; Lust, J.A.; Garcia, A.D.; Tiffany, A.J.; Heneine, W.; Switzer, W.M. Short communication: Absence of evidence of HTLV-3 and HTLV-4 in patients with large granular lymphocyte (LGL) leukemia. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2008, 24, 1503–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, D.U.; Proietti, F.A.; Ribas, J.G.; Araújo, M.G.; Pinheiro, S.R.; Guedes, A.C.; Carneiro-Proietti, A.B. Epidemiology, treatment, and prevention of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1-associated diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, A.L.; Farré, L. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2008, 83, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, A.Q. Update on Neurological Manifestations of HTLV-1 Infection. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2015, 17, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarbakhsh, S.; Taylor, G.P. High prevalence of bronchiectasis is linked to HTLV-1-associated inflammatory disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, M.M.N.; Giozza, S.P.; dos Santos, A.L.M.A.; Carvalho, E.M.; Araújo, M.I. Frequência de doenças reumáticas em indivíduos infectados pelo HTLV-1. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2006, 46, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, A.L.; Oliveira, M.F. Infective dermatitis associated with the HTLV-I (IDH) in children and adults. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2005, 80, S364–S369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoi, K.; Watanabe, T.; Uchimaru, K.; Okayama, A.; Kato, S.; Kawamata, T.; Kurozumi-Karube, H.; Horiguchi, N.; Zong, Y.; Yamano, Y.; et al. Updates on HTLV-1 Uveitis. Viruses. 2022, 14, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, A.; Hall, W.W. Human T-lymphotropic virus type II and neurological disease. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 56, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, S.; Barile, M.E.; Frutos, M.C.; Vicente, A.C.P.; Gallego, S.V. Neurodegenerative disease in association with sexual transmission of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 2 subtype b in Argentina. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 116, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roucoux, D.F.; Murphy, E.L. The epidemiology and disease outcomes of human T-lymphotropic virus type II. AIDS Rev. 2004, 6, 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, B.L.I.; Rodrigues, F.E.C.; Tsukimata, M.Y.; Botelho, B.J.S.; Santos, L.C.C.; Pereira Neto, G.S.; Lima, A.C.R.; André, N.P.; Galdino, S.M.; Monteiro, D.C.; et al. Fibromyalgia in patients infected with HTLV-1 and HTLV-2. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1419801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, K.; Origuchi, T.; Takashima, H.; Iwata, K.; Katamine, S.; Nagataki, S. High seroprevalence of anti-HTLV-I antibody in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 39, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, O.S.; Rodgers-Johnson, P.; Mora, C.; Char, G. HTLV-1 and polymyositis in Jamaica. Lancet 1989, 2, 1184–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonzetti, L.S.; Menna-Barreto, M.; Schoeler, M.; Cichoski, L.; Antonini, E.; Staub, H. High prevalence of HTLV-I infection among patients with rheumatoid arthritis living in Porto Alegre, Brazil. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 1999, 20, A54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, K.; Matsuoka, N.; Ida, H.; Nakashima, M.; Sakai, M.; Sakito, S.; Kawakami, A.; Terada, K.; Shimada, H.; Kawabe, Y.; et al. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome with antibodies to HTLV-I: Clinical and laboratory features. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1992, 51, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, K.; Katamine, S.; Eguchi, K.; Moriuchi, R.; Kita, M.; Shimada, H.; Yamashita, I.; Iwata, K.; Tsuji, Y.; Nagataki, S.; et al. Prevalence of serum and salivary antibodies to HTLV-1 in Sjögren’s syndrome. Lancet 1994, 344, 1116–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motokawa, S.; Hasunuma, T.; Tajima, K.; Krieg, A.M.; Ito, S.; Iwasaki, K.; Nishioka, K. High prevalence of arthropathy in HTLV-I carriers on a Japanese island. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1996, 55, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Maruyama, I.; Maruyama, Y.; Kitajima, I.; Nakajima, Y.; Higaki, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Miyasaka, N.; Osame, M.; Nishioka, K. Arthritis in patients infected with human T lymphotropic virus type I. Clinical and immunopathologic features. Arthritis Rheum. 1991, 34, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caskey, M.F.; Morgan, D.J.; Porto, A.F.; Giozza, S.P.; Muniz, A.L.; Orge, G.O.; Travassos, M.J.; Barrón, Y.; Carvalho, E.M.; Glesby, M.J. Clinical manifestations associated with HTLV type I infection: A cross-sectional study. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2007, 23, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umekita, K.; Okayama, A. HTLV-1 Infection and Rheumatic Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umekita, K. Effect of HTLV-1 Infection on the Clinical Course of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Viruses 2022, 14, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.; Yoshikawa, G.T.; Koyama, R.V.; Dias, G.A.; Fujihara, S.; Fuzii, H.T. HTLV-1, Immune Response and Autoimmunity. Viruses 2015, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, A.; Takenaka, Y.; Noda, Y.; Ueno, Y.; Shichikawa, K.; Sato, K.; Miyasaka, N.; Nishioka, K. Adult T cell leukemia presenting with proliferative synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988, 31, 1076–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernant, J.C.; Buisson, G.; Magdeleine, J.; De Thore, J.; Jouannelle, A.; Neisson-Vernant, C.; Monplaisir, N. T-lymphocyte alveolitis, tropical spastic paresis, and Sjögren syndrome. Lancet 1988, 1, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, I.; Yamamoto, K.; Sato, K.; Nakajima, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Maruyama, I.; Osame, M.; Nishioka, K. Detection of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I proviral DNA and its gene expression in synovial cells in chronic inflammatory arthropathy. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakura, Y.; Saijo, S.; Kioka, Y.; Nakayama-Yamada, J.; Itagaki, K.; Tosu, M.; Asano, M.; Kanai, Y.; Kakimoto, K. Autoimmunity induction by human T cell leukemia virus type 1 in transgenic mice that develop chronic inflammatory arthropathy resembling rheumatoid arthritis in humans. J. Immunol. 1995, 155, 1588–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalan-Soares, B.; Carneiro-Proietti, A.B.F.; Proietti, F.A. Heterogeneous geographic distribution of human T-cell lymphotropic viruses I and II (HTLV-I/II): Serological screening prevalence rates in blood donors from large urban areas in Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública. 2005, 21, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, F.T.; Sousa, R.S.; Gomes, J.L.C.; Vallinoto, M.C.; Lima, A.C.R.; Lima, S.S.; Freitas, F.B.; Feitosa, R.N.M.; Rangel da Silva, N.A.M.; Machado, L.F.A.; et al. The Relevance of a Diagnostic and Counseling Service for People Living With HTLV-1/2 in a Metropolis of the Brazilian Amazon. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 864861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Guia de Manejo Clínico da Infecção pelo HTLV; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/central-de-conteudo/publicacoes/2022/guia_htlv_internet_24-11-21-2_3.pdf/view (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Porto, C.C. Semiologia Médica; Editora Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017; 1376p. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenstein-Schainberg, C.; Favarato, M.H.S.; Ranza, R. Conceitos atuais e relevantes sobre artrite psoriásica. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2012, 52, 98–106. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbr/a/pn5PcdM69CDnBqk4nrGBN4M/ (accessed on 15 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, L.C.F.; Caramelli, P.; Proietti, A.B.F.C. O vírus linfotrópico de células T humanos tipo 1 (HTLV-1): Quando suspeitar da infecção? Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2010, 56, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosadas, C.; Brites, C.; Arakaki-Sánchez, D.; Casseb, J.; Ishak, R. Protocolo Brasileiro para Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis 2020: Infecção pelo vírus linfotrópico de células T humanas (HTLV). Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2021, 30, e2020605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, B.A.; Catalan-Soares, B.; Proietti, F. Higher prevalence of fibromyalgia in patients infected with human T cell lymphotropic virus type I. J. Rheumatol. 2006, 33, 2300–2303. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, L.S.; Proietti, F.A. Fibromyalgia and infectious stress: Possible associations between fibromyalgia syndrome and chronic viral infections. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2005, 45, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinjo, S.K.; Moreira, C. Livro da Sociedade Brasileira de Reumatologia, 2nd ed.; Manole: Barueri, Brazil, 2021; 1814p. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | HTLV-1/2 | HTLV-1 | HTLV-2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 11 | 73.3 | 9 | 81.8 | 3 | 75.0 |

| Male | 4 | 26.7 | 2 | 18.2 | 1 | 25.0 |

| Age | ||||||

| Mean age ± SD | 53.40 ± 16.00 | 51 ± 17.32 | 60 ± 10.80 | |||

| Range | 30~81 | 30~81 | 51~74 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 5 | 33.3 | 4 | 36.4 | 1 | 25.0 |

| Brown | 6 | 40.0 | 4 | 36.4 | 2 | 50.0 |

| White | 4 | 26.7 | 3 | 27.2 | 1 | 25.0 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 7 | 46.7 | 6 | 54.5 | 1 | 25.0 |

| Single | 5 | 33.3 | 3 | 27.3 | 2 | 50.0 |

| Divorced | 1 | 6.7 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Widowed | 2 | 13.3 | 1 | 9.1 | 1 | 25.0 |

| Joint Manifestations | HTLV-1 (n = 10) | HTLV-2 (n = 3) | HTLV-1/2 (n = 13) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Arthralgia | 10 | 76.9 | 3 | 23.1 | 13 | 100 |

| Monoarthralgia | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Symmetrical oligoarthralgia | 2 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15.4 |

| Asymmetrical oligoarthralgia | 2 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15.4 |

| Symmetrical polyarthralgia | 5 | 50 | 2 | 66.7 | 7 | 53.8 |

| Asymmetrical polyarthralgia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Arthritis | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 |

| Monoarthritis | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50 |

| Symmetrical oligoarthritis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asymmetrical oligoarthritis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Symmetrical polyarthritis | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50 |

| Symmetrical polyarthritis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other joint manifestations | 6 | 66.7 | 3 | 33.3 | 9 | 100 |

| Crepitus | 5 | 83.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 7 | 77.8 |

| Morning stiffness (>30 min) | 1 | 16.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 |

| Joint effusion | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 11.1 |

| Location of affected joints | 28 | 75.6 | 9 | 24.4 | 37 | 100 |

| Hands | 5 | 17.8 | 2 | 22.2 | 7 | 19 |

| Wrists | 2 | 7.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.4 |

| Elbows | 2 | 7.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.4 |

| Shoulders | 4 | 14.2 | 1 | 11.2 | 5 | 13.5 |

| Feet | 3 | 10.8 | 2 | 22.2 | 5 | 13.5 |

| Ankles | 3 | 10.8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 |

| Knees | 5 | 17.8 | 2 | 22.2 | 7 | 19 |

| Hips | 4 | 14.2 | 2 | 22.2 | 6 | 16.2 |

| Muscle Pain | HTLV-1 (n = 5) | HTLV-2 (n = 3) | HTLV-1/2 (n = 8) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Myalgia | 5 | 62.5 | 3 | 37.5 | 8 | 100 |

| Localized pain | 3 | 60 | 1 | 25 | 4 | 50 |

| Diffuse body pain | 2 | 40 | 2 | 75 | 4 | 50 |

| Fibromyalgia characteristics for diffuse body pain | 2 | 50 | 2 | 50 | 4 | 100 |

| Chronic pain | 2 | 25 | 2 | 25 | 4 | 25 |

| Tender points | 2 | 25 | 2 | 25 | 4 | 25 |

| Sleep disorders | 2 | 25 | 2 | 25 | 4 | 25 |

| Mood disorders | 2 | 25 | 2 | 25 | 4 | 25 |

| Rheumatological Diseases | HTLV-1 (n = 11) | HTLV-2 (n = 4) | HTLV-1/2 (n = 15) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Fibromyalgia | 2 | 18.2 | 2 | 50 | 4 | 26.6 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.6 |

| Osteoarthritis | 3 | 27.3 | 2 | 50 | 5 | 33.3 |

| Epicondylitis | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.6 |

| Low back pain | 1 | 9.1 | 1 | 25 | 2 | 13.3 |

| Neck pain | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.6 |

| Chondromalacia | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.6 |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | 2 | 18.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13.2 |

| Anserine tendonitis | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.6 |

| Trochanteric bursitis | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsukimata, M.Y.; da Silva, B.L.I.; Pereira, L.M.S.; Botelho, B.J.S.; Santos, L.C.C.; Bichara, C.D.A.; Neto, G.d.S.P.; Lima, A.C.R.; Rodrigues, F.E.d.C.; André, N.P.; et al. Rheumatological Manifestations in People Living with Human T-Lymphotropic Viruses 1 and 2 (HTLV-1 and HTLV-2) in Northern Brazil. Viruses 2025, 17, 874. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070874

Tsukimata MY, da Silva BLI, Pereira LMS, Botelho BJS, Santos LCC, Bichara CDA, Neto GdSP, Lima ACR, Rodrigues FEdC, André NP, et al. Rheumatological Manifestations in People Living with Human T-Lymphotropic Viruses 1 and 2 (HTLV-1 and HTLV-2) in Northern Brazil. Viruses. 2025; 17(7):874. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070874

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsukimata, Márcio Yutaka, Bianca Lumi Inomata da Silva, Leonn Mendes Soares Pereira, Bruno José Sarmento Botelho, Luciana Cristina Coelho Santos, Carlos David Araújo Bichara, Gabriel dos Santos Pereira Neto, Aline Cecy Rocha Lima, Francisco Erivan da Cunha Rodrigues, Natália Pinheiro André, and et al. 2025. "Rheumatological Manifestations in People Living with Human T-Lymphotropic Viruses 1 and 2 (HTLV-1 and HTLV-2) in Northern Brazil" Viruses 17, no. 7: 874. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070874

APA StyleTsukimata, M. Y., da Silva, B. L. I., Pereira, L. M. S., Botelho, B. J. S., Santos, L. C. C., Bichara, C. D. A., Neto, G. d. S. P., Lima, A. C. R., Rodrigues, F. E. d. C., André, N. P., Galdino, S. M., Monteiro, D. C., Silva, L. d. C. d. S., Araújo, L. C. O., Matos Carneiro, J. R., Cruz, R. d. B. P., Ishak, R., Vallinoto, A. C. R., Klemz, B. N. d. C., & Vallinoto, I. M. V. C. (2025). Rheumatological Manifestations in People Living with Human T-Lymphotropic Viruses 1 and 2 (HTLV-1 and HTLV-2) in Northern Brazil. Viruses, 17(7), 874. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070874