Hollow Protein Fibers Templated Synthesis of Pt/Pd Nanostructures with Peroxidase-like Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Preparation of Ultra-Long TMVF Template

2.2. The Mineralization of TMVF-Templated Metallic Nanostructures

2.3. The Measurement of Peroxidase-like Activity of TMVF-Templated Pt/Pd NWs

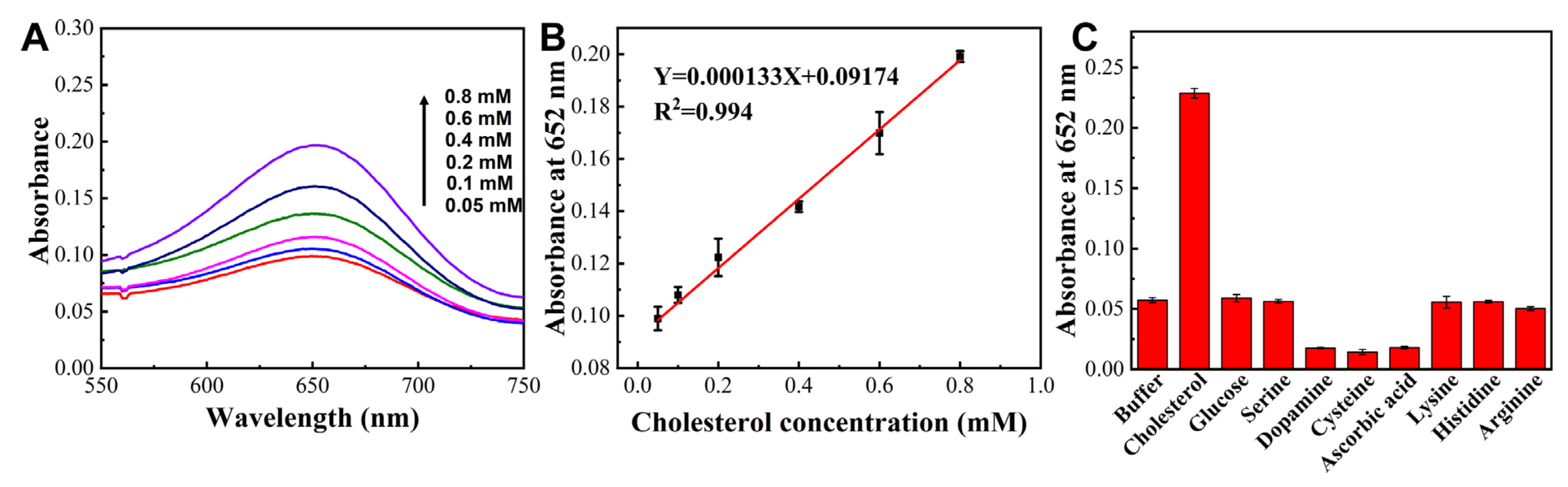

2.4. Pt/Pd NWs Assisted Cholesterol Detection

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiong, R.; Wu, W.L.; Lu, C.H.; Coelfen, H. Bioinspired Chiral Template Guided Mineralization for Biophotonic Structural Materials. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2206509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiadou, D.; Carneiro, K.M.M. DNA Nanostructures as Templates for Biomineralization. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, J.L.; Fernández, M.S. Polysaccharides and Proteoglycans in Calcium Carbonate-Based Biomineralization. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4475–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.X.; Cheng, L.D.; Yu, J.Y.; Si, Y.; Ding, B. Biomimetic Bouligand Chiral Fibers Array Enables Strong and Superelastic Ceramic Aerogels. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Cao, Y.Y.; Huang, Z.H.; Duan, Y.Y.; Che, S.N. Silica Biomineralization via the Self-Assembly of Helical Biomolecules. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Luo, J.; You, M.; Yang, T.; Deng, Y.B.; Yang, H.; et al. Albumin-Templated Platinum (II) Sulfide Nanodots for Size-Dependent Cancer Theranostics. Acta Biomater. 2023, 155, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocik, J.M.; Wright, D.W. Biomimetic Mineralization of Noble Metal Nanoclusters. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigil, T.N.; Spangler, L.C. Understanding Biomineralization Mechanisms to Produce Size-Controlled, Tailored Nanocrystals for Optoelectronic and Catalytic Applications: A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 18626–18654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.J.; Le Saux, G.; Gao, J.; Buffeteau, T.; Battie, Y.; Barois, P.; Ponsinet, V.; Delville, M.H.; Ersen, O.; Pouget, E.; et al. GoldHelix: Gold Nanoparticles Forming 3D Helical Superstructures with Controlled Morphology and Strong Chiroptical Property. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 3806–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.G.; Pan, Y.J.; Chen, B.Q.; Lu, X.C.; Xu, Q.X.; Wang, P.; Kankala, R.K.; Jiang, N.N.; Wang, S.B.; Chen, A.Z. Protein-guided Biomimetic Nanomaterials: A Versatile Theranostic Nanoplatform for Biomedical Applications. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.T.; Sun, Y.X.; Cheng, Q.C.; Yang, Z.Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z.P.; Yang, M.Y.; Shuai, Y.J. Silk Protein-Mediated Biomineralization: From Bioinspired Strategies and Advanced Functions to Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 33191–33206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhari, K.; Xavier, P.L.; Pradeep, T. Understanding the Evolution of Luminescent Gold Quantum Clusters in Protein Templates. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 8816–8827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.N.; Blum, A.S.; Mauzeroll, J. Tunable Assembly of Protein Enables Fabrication of Platinum Nanostructures with Different Catalytic Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 52588–52597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasteen, N.D.; Harrison, P.M. Mineralization in ferritin: An Efficient Means of Iron Storage. J. Struct. Biol. 1999, 126, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, T.; Strable, E.; Willits, D.; Aitouchen, A.; Libera, M.; Young, M. Protein Engineering of a Viral Cage for Constrained Nanomaterials Synthesis. Adv. Mater. 2002, 14, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Gao, D.; Zhai, X.M.; Chen, Y.H.; Fu, T.; Wu, D.M.; Zhang, Z.P.; Zhang, X.E.; Wang, Q.B. Tunable, Discrete, Three-Dimensional Hybrid Nanoarchitectures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4202−4205. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Kankala, R.K.; Ma, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.-B.; Chen, A.-Z. Hollow Tobacco Mosaic Virus Coat Protein Assisted Self-Assembly of One-Dimensional Nanoarchitectures. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 540−545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Peydayesh, M.; Lu, J.D.; Zhou, J.T.; Benedek, P.; Schäublin, R.; You, S.J.; Mezzenga, R. Amyloid-Templated Palladium Nanoparticles for Water Purification by Electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, 202116634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, S.; Park, S.; Jeong, J.; Kim, K. Aggregation-Free Optical and Colorimetric Detection of Hg(II) with M13 Bacteriophage-Templated Au Nanowires. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 161, 112237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.T.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, Y.J.; Du, M.M.; Wang, Q.B. Precise Self-Assembly of Nanoparticles into Ordered Nanoarchitectures Directed by Tobacco Mosaic Virus Coat Protein. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1901485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Xiao, Y.; Hao, H.B.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, R.K. Biomineralization State of Viruses and Their Biological Potential. Chemistry 2018, 24, 11518–11529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.T.; Ma, J.Y.; Kankala, R.K.; Yu, Q.Q.; Wang, S.B.; Chen, A.Z. Recent Advances in Fabrication of Well-Organized Protein-Based Nanostructures. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 2021, 4, 4039–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, M.B.; Sandhage, K.H.; Naik, R.R. Protein- and Peptide-Directed Syntheses of Inorganic Materials. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4935–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Zhou, Y.H.; Yang, H.C.; Jin, H.L.; Ke, Y.G.; Wang, Q.B. Interfacially Bridging Covalent Network Yields Hyperstable and Ultralong Virus-Based Fibers for Engineering Functional Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 18249–18255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.N.; Saunders, K.; Thuenemann, E.C.; Evans, D.J.; Lomonossoff, G.P. Designer-Length Palladium Nanowires Can Be Templated by The Central Channel of Tobacco Mosaic Virus Nanorods. Virology 2022, 577, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.; Zhou, Z.H. Hydrogen-Bonding Networks and RNA Bases Revealed by Cryo Electron Microscopy Suggest a Triggering Mechanism for Calcium Switches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9637–9642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champness, J.N.; Bloomer, A.C.; Bricogne, G.; Butler, P.J.G.; Klug, A. Structure of Protein Disk of Tobacco Mosaic Virus To 5Å Resolution. Nature 1976, 259, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Durham, A.C.H.; Klug, A. Polymerization of Tobacco Mosaic Virus Protein and Its Control. Nat. New Biol. 1971, 229, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, J.T.; Wang, Q.B. Site-Selective Nucleation and Controlled Growth of Gold Nanostructures in Tobacco Mosaic Virus Nanotubulars. Small 2015, 11, 2505–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, R.; Muraoka, M.; Seki, M.; Tabata, H.; Yamashita, I. Synthesis of CoPt and FePt Nanowires Using the Central Channel of Tobacco Mosaic Virus as a Biotemplate. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 2389–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, M.; Sumser, M.; Bittner, A.M.; Wege, C.; Jeske, H.; Martin, T.P.; Kern, K. Spatially Selective Nucleation of Metal Clusters on the Tobacco Mosaic Virus. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2004, 14, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.N.; Liu, W.Q.; Wu, X.C.; Gao, X.F. Mechanism of pH-Switchable Peroxidase and Catalase-Like Activities of Gold, Silver, Platinum and Palladium. Biomaterials 2015, 48, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, F.; Shahpar, M.G.; Rasti, B.; Sharifi, M.; Saboury, A.A.; Rezayat, S.M.; Falahati, M. Nanozymes with Intrinsic Peroxidase-like Activities. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 278, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Q. Tobacco Mosaic Virus with Peroxidase-Like Activity for Cancer Cell Detection through Colorimetric Assay. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 2946–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Bao, M.; Zhang, L.; Carraro, C.; Maboudian, R.; Liu, A.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. Pd Nanoclusters Confined in ZIF-8 Matrixes for Fluorescent Detection of Glucose and Cholesterol. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 9132–9142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Wu, R.; Chong, Y.; Fang, G.; Jiang, X.; Pan, Y.; Chen, C.; Yin, J.-J. Synthesis of Pt Hollow Nanodendrites with Enhanced Peroxidase-Like Activity against Bacterial Infections: Implication for Wound Healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1801484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Hou, L.; Xu, M.; Tang, D. Enhanced Colorimetric Immunoassay Accompanying with Enzyme Cascade Amplification Strategy for Ultrasensitive Detection of Low-Abundance Protein. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, B.; Fan, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J. Hollow Protein Fibers Templated Synthesis of Pt/Pd Nanostructures with Peroxidase-like Activity. Viruses 2025, 17, 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121627

Huang B, Fan M, Li Y, Zhang T, Zhang J. Hollow Protein Fibers Templated Synthesis of Pt/Pd Nanostructures with Peroxidase-like Activity. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121627

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Beizhe, Mengting Fan, Yuhan Li, Ting Zhang, and Jianting Zhang. 2025. "Hollow Protein Fibers Templated Synthesis of Pt/Pd Nanostructures with Peroxidase-like Activity" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121627

APA StyleHuang, B., Fan, M., Li, Y., Zhang, T., & Zhang, J. (2025). Hollow Protein Fibers Templated Synthesis of Pt/Pd Nanostructures with Peroxidase-like Activity. Viruses, 17(12), 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121627